Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Revista Colombiana de Cardiología

versão impressa ISSN 0120-5633

Rev. Colomb. Cardiol. vol.21 no.6 Bogota nov./dez. 2014

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rccar.2014.11.003

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rccar.2014.12.001

How to consult databases?

¿Cómo consultar bases de datos?

Janneth Olartea

aBiblioteca Fundación Cardioinfantil-Instituto de Cardiología, Bogotá, Colombia

Received November 24, 2014; Accepted December 17, 2014

Correo electrónico:biblioteca@cardioinfantil.org

The activities inherent to the medicinal practice require additional input to the medical devices and medicines, information, and the major sources of access are bibliographic data bases.1 These should be consulted as part of the process of critical evaluation of literature, because they are resources supported by academic and scientific authorities,2 that differentiate them from the thousands of sources of information available on the Internet, App stores and the market in general.

The medical professional should consult databases when he requires bibliographic information for health care practice, teaching or research, which are the activities that generate him questions. The best route to identify and consult the relevant database is to start with the recommendations of the specialized literature,3 the basic texts of clinical epidemiology4 and research, manuals of elaboration of Guidelines of Clinical Practice,5 the systematic revisions,6 the series of publications about the use of medical literature,7 pages, blogs, social networks and different technologies of information and communication, whose authorship be of recognized organizations.

In health the first portals or websites dedicated to the collection of access to these databases emerged.8 One of the most comprehensive Web sites is the information system set up jointly by the National Institute of Health (NIH), the National Center for Biotechnology (NCBI) and the National Library of Medicine (NLM) in the US, including recognized resources such as PubMed, Ominy Medline Plus.

Since its inception, the Colombian Journal of Cardiology has been governed by the regulations and guidelines of authorities on topics of scientific publications in the world, allowing it to be indexed in databases such as Lilacs, Science Direct and Scopus. This editorial is part of the strategies focused on training and educating specialists who use it in their routine update on issues of cardiology and cardiovascular surgery, in identifying and using relevant bibliographic data bases for their research projects as well as in creating manuscripts and in decision making.

Today, thanks to the popularity of the Internet and to programs led by organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO),9 to achieve universal access to scientific knowledge produced in medicine and related sciences, with the premise that “scientific information is a tool for improving public health”, projects of open access and many databases that do not require payment to be consulted especially in lower income countries, have been created.

The challenge now is to know how to use databases adequately.10 Therefore, the reader will find below a series of recommendations to make the query:

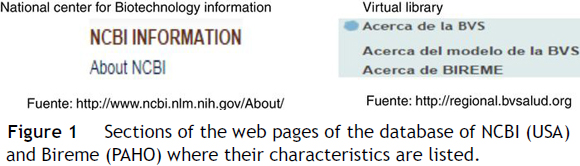

- Know the general characteristics of the resource. Contents, update, authors, publishers, reviewers and target audience; that information is available in sections identified by phrases or terms such as about, presentation, introduction (Fig. 1).

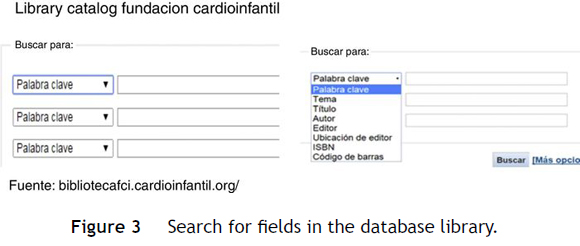

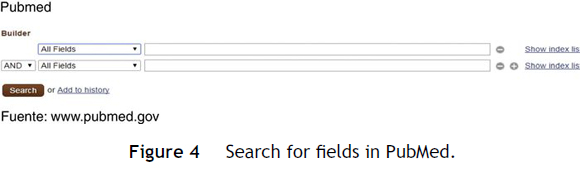

- Descriptive elements. Every document (book, magazine article, trial, video, image, interview) has elements that constitute points of entry of information databases. Use this information when searching: title, author, abstract or introduction, keywords or descriptors (later, this topic will be deepened). An advantage of information in health sciences is the precision of the titles and content writing; literary figures are rarely used. When no specific search field is stablished, the machines review these elements and then the content to generate results. Search by fields will give more accurate results (Figs. 3 and 4).

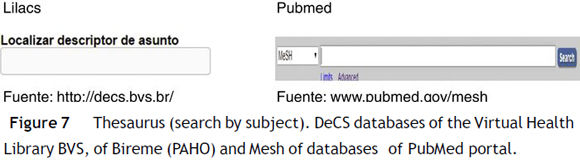

- Search by themes or descriptors. Some sciences have created Thesaurus or specialized lists of words, exclusive or with a connotation to that science. These provide a brief description of the concept, the list of synonymous terms that should be replaced by the agreed term and taxonomic structure of the term (the most famous Thesaurus in health sciences is the MESH, translated into Spanish and Portuguese by Bireme, entity attached to the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), as DECS). They allow more specific results and require the knowledge of these terms by those who visit. All bibliographic, academic and scientific databases offer this type of search (Fig. 7).

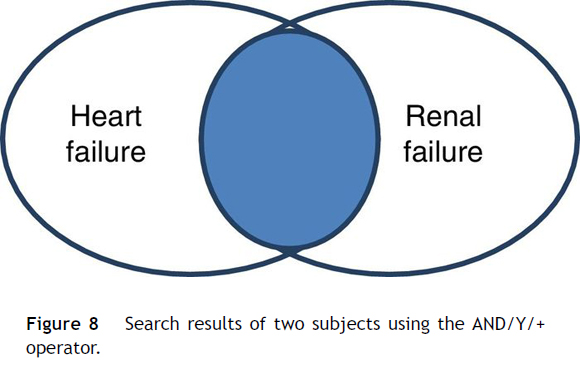

- Advanced searches. The databases let you combining several terms, themes with themes, themes with authors, with journal titles, with names of institutions, among others, by means of Boolean operators and use of parentheses. The way you write operators may vary in terms of sentences, syllables or signs; for example, the intersection is represented by: Y, AND, +, so you should check the tutorials, manuals and user guides before using database. The following are the most used.

- Complex searches. These are achieved using multiple Boolean operators and parentheses.

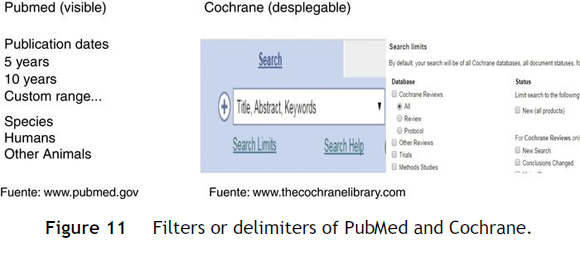

- Use of delimiters, filters or boundaries. These are aspects that allow to select characteristics of the results that reduce their number; they make them more specific. There are language delimiters, age of patients, type of document, type of studies, publication date, document formatting, among others. They are usually in a visible alternative menu; on other occasions they must be deployed (Fig. 11).

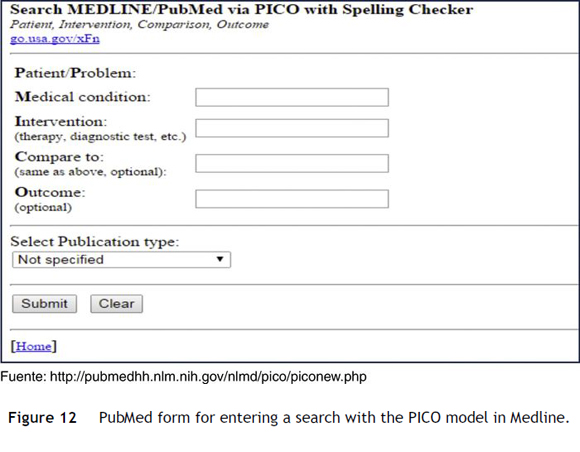

- Use of forms. There are resources that have pre-designed forms to enter the query. Learn to use them through the tutorials which will help you to save time and get more accurate results to meet your information needs (Fig. 12).

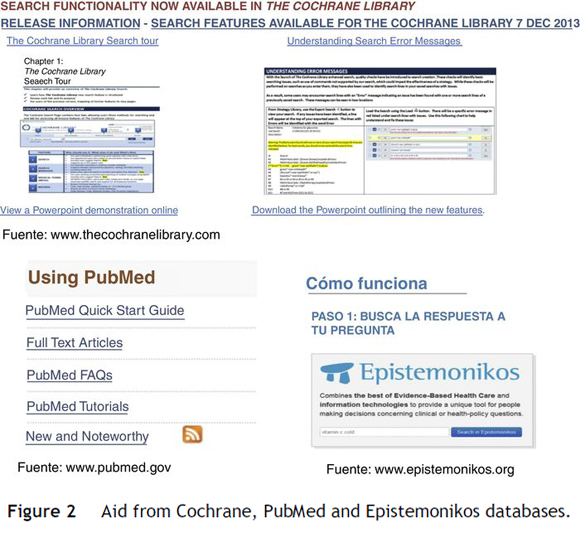

Each database has a structure for consultation and characteristic support symbols such as wildcards (characters that replace the end of a word to make the most sensitive search; some are: *, &, %. For example: Cardio * will recover pediatric cardiology, cardiac therapy, cardioplegia, cardiology) and Boolean operators (AND, Y, +). These grants are consulted in user manuals, tutorials, user guides and instructions (Fig. 2).

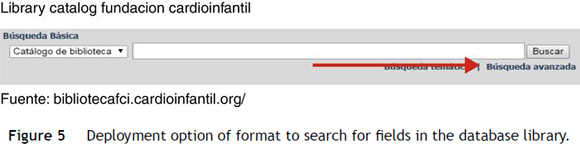

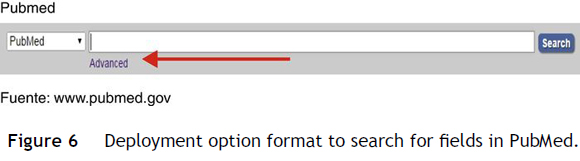

In the first screen these options are not displayed, identify advanced search section or search by fields to deploy them (Figs. 5 and 6).

When you create a document, assign descriptors, which except for proper names, unreleased tracks, discoveries or inventions, are taken from Thesauri in order that they can be easily recoverable in databases.

AND or Y (intersection), all combined terms will be mandatory in results; only documents where appear simultaneously all terms, phrases, names, formulas and acronyms related by the operator will be recovered. The results will be very specific (Fig. 8).

Example: To find all the items about heart failure in patients with renal failure

Heart failure AND renal failure

Heart failure Y renal failure

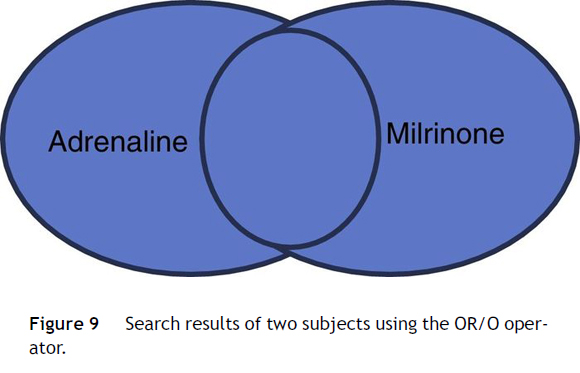

OR or O (union): any of the terms combined with that operator will be recovered independently, whether they are or not simultaneously in the document. The results will be very broad; it is a highly sensitive connector. Is used to connect synonyms, equivalents or variables that have the same validity or importance (Fig. 9).

Example: to retrieve articles that speak of either of these two drugs

Adrenaline OR milrinone

Adrenaline O milrinone

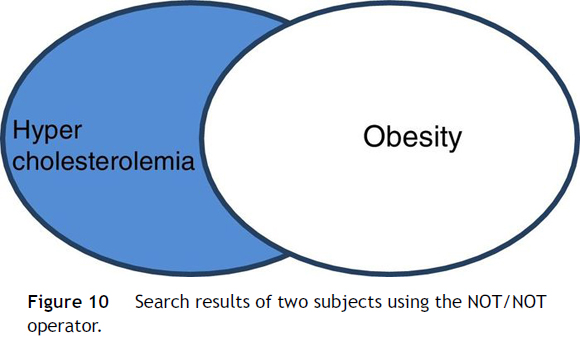

NOT or NO (difference): the subject not wanted to appear in the results is located after the operator. It is the last to be included when a complex query is designed, i.e. with several operators at the same time (Fig. 10).

Example: you want to do a literature search about hypercholesterolemia in non-obese patients

Hypercholesterolemia NOT obesity

Hypercholesterolemia NO obesity

Example: hypercholesterolemia unrelated to obesity in patients with heart and renal failure who take milrinone or dopamine:

(Heart failure AND renal failure) AND (milrinone OR dopamine) AND (hypercholesterolemia NOT obesity)

In some databases the boxes to write each term are predetermined whereby is necessary to run multiple searches, one per operator, and then combine the results.

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

1. Covell D.G., Uman G.C., Manning P.R. Information needs in office practice: are they being met?. Ann Intern Med1985;103:596-9

2. Cómo encontrar la mejor evidencia actual y hacer que la mejor evidencia nos, encuentre. Medicina basada en la evidencia: Como practicar y enseñar la MBE, 3rd ed., Elsevier, (2006) pp. 31-65

3. Berwanger O., Avezum A., Guimarães H.P. Evidence-based cardiology: where to find evidence. Arq Bras Cardiol2006;86:56-60

4. Fletcher R.H. Epidemiología clínica: aspectos fundamentales. 2nd ed., Doyma, (2007)

5. NICE The guidelines manual. NICE, (2012)

6. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011], The Cochrane Collaboration, (2011)

7. Users’ guides to the medical literature: a manual for evidence-based clinical practice, 2nd ed., McGraw Hill, (2008)

8. Alfonso F., Ambrosio G., Ector H., Gonçalves L., Pinto F., Timmis A., Vardas P. Cardiovascular Journals and the New European Society of Cardiology search engine. Eur Heart J2013;34:3161-3

9. Katikireddi S.V. HINARI: bridging the global information divide. BMJ2004;328:1190-3

10. Brettle A. Information skills training: a systematic review of the literature. Health Info Libr J2003;20:3-9

1. Covell D.G., Uman G.C., Manning P.R. Information needs in office practice: are they being met?. Ann Intern Med.1985;103:596-9. [ Links ]

2. Straus S, Richardson W, Glaziou P, Haynes R. Medicina basada en la evidencia: Cómo practicar y enseñar la MBE. 3. ed. Elsevier. Madrid, (2006) p. 31-65 [ Links ]

3. Berwanger O., Avezum A., Guimarães H.P. Evidence-based cardiology: where to find evidence. Arq Bras Cardiol.2006;86:56-60. [ Links ]

4. Fletcher R.H. Epidemiología clínica: aspectos fundamentales. 2 a. ed., Doyma, (2007) . [ Links ]

5. Nice. The Guidelines manual 2012. London: NICE. {consultado 1 Oct 2014}. Disponible en: http://www.nice.org.uk/article/PMG6. [ Links ]

6. Higgins JPT, Green S, editores. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 { actualizado Mar 2011} . The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011 { consultado 15 Sep 2014} . Disponible en: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org. [ Links ]

7. Guyatt G, Rennie D, Meade M, Cook D. Users' guides to the medical literature: A manual for evidence-based clinical practice, 2 nd., ed. McGraw Hill, (2008) [ Links ]

8.Alfonso F, Ambrosio G, Ector H, Goncalves L, Pinto F, Timmis A, Vardas P, editors. Network European Society of Cardiology task Force. Nacional Society. Cardiovascular search engine. Eur Heart J.2013;34:3161-3. [ Links ]

9. Katikireddi S.V. HINARI: bridging the global information divide. BMJ.2004;328:1190-3. [ Links ]

10. Brettle A. Information skills training: a systematic review of the literature. Health Info Libr J.2003;20:3-9. [ Links ]

texto em

texto em