Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

How

versión impresa ISSN 0120-5927

How vol.21 no.2 Bogotá jul./dic. 2014

https://doi.org/10.19183/how.21.2.7

http://dx.doi.org/10.19183/how.21.2.7

Using SFL as a Tool for Analyzing Students' Narratives

El uso de la lingüística sistémica funcional para analizar las narrativas de los estudiantes

Doris Correaa

Camilo Domínguezb

aUniversidad de Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia. E-mail: doris.correa@udea.edu.co.

bUniversidad de Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia. E-mail: camilo27.dominguez@gmail.com.

Received: January 10, 2014. Accepted: September 15, 2014.

How to cite this article (APA 6th ed.):

Correa, D., & Domínguez, C. (2014). Using SFL as a tool for analyzing students' narratives. HOW, 21(2), 112-133. http://dx.doi.org/10.19183/how.21.2.7

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. License Deed can be consulted at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Traditionally, at universities, English as a foreign language instructors have used a series of approaches to teach students how to write academic texts in English from both teacher preparation and regular programs. In spite of this, students continue to have problems writing the academic texts required of them in the different courses. Concerned with this issue, a group of English as a Foreign Language writing instructors from a Teacher Education Program in Medellín engaged in the study of Systemic Functional Linguistics. The purpose of this article is to report the insights that one of these instructors gained once he began using these theories to analyze a narrative text produced by one of the students in his class.

Key words: EFL writing, narratives, narrative writing, Systemic Functional Linguistics, text analysis.

Tradicionalmente, en las universidades los instructores de inglés como lenguaje extranjera han usado una serie de metodologías para enseñar a sus estudiantes, tanto a los que se están preparando para ser profesores como para los que no, cómo escribir textos académicos en inglés. No obstante, los estudiantes continúan presentando problemas al escribir textos académicos para sus clases. Preocupados con esta situación, varios instructores de un programa de educación de docentes de lenguas extranjeras en Medellín iniciaron el estudio de la lingüística sistémica funcional. El propósito de este artículo es presentar los aprendizajes que un miembro de este grupo obtuvo cuando empezó a usar estas teorías para analizar el texto narrativo producido por una de sus estudiantes.

Palabras clave: análisis de textos, escritura en inglés como lengua extranjera, escritura narrativa, lingüística sistémica funcional, narrativas.

Introduction

For years Colombian university instructors of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) have tried to teach writing to students using a variety of approaches which include process writing (Artunduaga Cuéllar, 2013; Rivera Barreto, 2011; Zúñiga & Macías, 2006), collaborative writing (Robayo Luna & Hernández Ortiz, 2013), and genre-based approaches (Chala & Chapetón, 2013; Chapetón & Chala, 2013). In spite of their efforts, instructors often complain that students frequently get to the advanced courses unprepared to write the academic texts required for these courses (Cárdenas, Nieto, & Martin, 2005; Cárdenas, Nieto, Bellanger, Cortés, & Ruger, 2005; Robayo Luna & Hernández Ortiz, 2013).

Concerned with this issue, we, the authors of this article, and five other EFL writing instructors from an EFL Teacher Education Program at a public university in Medellín began getting together every week in 2010 to study Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL). This is a theory of language proposed by Halliday (1978), which proposes, among other aspects, that when writers write they construct meaning at three different levels: the experiential level (field), the interpersonal level (tenor), and the textual level (mode) (Butt, Fahey, Feez, Spinks, & Yallop, 2006). As such, in analyzing students' texts, instructors need to pay attention to what students are doing at each of these levels, and not merely at what grammatical or syntactical rules they might be breaking (Schleppegrell, 2004).

As we studied these theories as a group, we also analyzed, in light of them, some of the texts that our students had produced in the EFL writing courses that we were teaching that semester. The analysis was made in terms of both how the students were constructing field, tenor, and mode, and how we, as instructors, could have better helped them improve their texts at each of these levels. The purpose of this article, then, is to present the analysis that Camilo, one of themembers of the study group, made of the narrative text produced by one of the students in his Written Communications II course. This analysis was made in terms of both how the student was constructing experiential, interpersonal, and textual meanings and how he could have better assisted the student in the writing of the text. It is our belief that the insights Camilo gained while conducting such an analysis can greatly help other EFL writing instructors who, as he, have been in charge of teaching writing without much training on what to look at when faced with students' texts or how to help students improve their texts.

To achieve this objective, in the following sections we first present a brief overview of SFL and of the narrative unit that Camilo taught. Then, we present an analysis of the text at three levels: field, tenor, and mode. As we do this, we describe the insights that Camilo gained as to how he could have better aided the student with her writing. Finally, we present some conclusions and implications for teaching, professional development, and research.

SFL and Narrative Writing

As can be gathered from the introduction, SFL is a theory of language that is different from other theories of language in several respects, particularly in its views of grammar and texts. First, to SFL scholars the grammar used to construct texts is not a rigid "set of abstract rules" (Thompson, 2004, p.6) that can be memorized and applied to all texts of a similar nature. Instead, it is a "system of choices" (p. 31) that is made according to purpose, context, and audience.

Second, to SFL scholars texts are determined by their social purpose and the situations in which they are produced (Schleppegrell, 2004). As for the former, although a text may have different purposes, they usually have an overall purpose or genre which may be to describe, to explain, or to narrate (Knapp & Watkins, 2005). Narratives, for example, usually have an overall purpose which is "to entertain" but they also may have other purposes such as "to gain and hold the reader's interest in a story . . . to teach or inform, to embody the writer's reflections on experience, and—perhaps most important—to nourish, and to extend the reader's imagination" (Derewianka, 2004, p. 40).

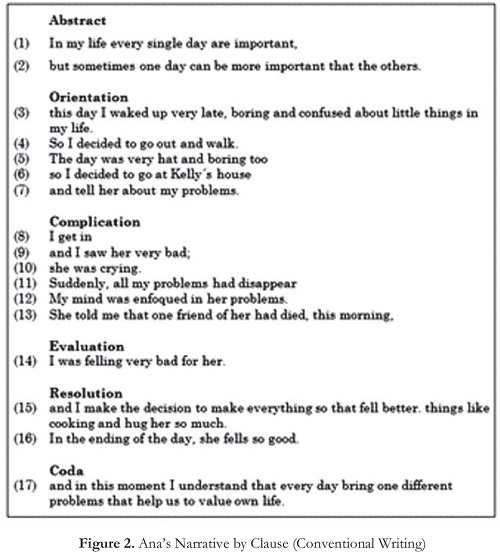

As for the latter, to SFL scholars texts are influenced by two contexts: the context of culture and the context of situation. The context of culture marks the genre features of a text or its structure. Narratives, for instance, often have an abstract, orientation, a sequence of events or complication (which might include a reflection on the problem and possible solutions), an evaluation, a resolution, and a coda (Knapp & Watkins, 2005). Each of these stages has a different purpose or function: The "abstract indicates what the story is about" (Cheng, 2008, p. 171). The orientation provides a sketch of this particular story, that is, it introduces the readers to the main characters of the narrative, indicates where the action is located and when it is taking place, establishes the atmosphere, foreshadows the action to follow, and makes the reader want to become involved in the story (Derewianka, 2004). The complication introduces a series of events during which there is "one or more problems for characters to resolve, involving problem and struggle episodes. Evaluation highlights the significance of events for characters and resolution to resolve these issues. Coda brings readers back to the present situation" (Cheng, 2008, p. 172).

The context of situation is comprised of field, tenor, and mode. Field refers to what the text is about (Eggins, 2004). To build it, authors use a series of linguistic resources such as participants (e.g., a person, a place or an object), processes (verbs), and circumstances (e.g., adverbial groups, prepositional phrases, and even nominal groups) (Butt et al., 2006). These resources adopt certain characteristics depending on the type of text. In narratives, participants are often "specific and individualized characters" (Cheng, 2008, p. 172), with "defined identities" (Derewianka, 2004, p. 42). To characterize and describe these participants, writers frequently use pre- and post-modifying elements, including adjectives, adverbs, -ed/-ing participles, prepositional phrases, and relative clauses (Fang, Schleppegrell, & Cox, 2006). Processes are mainly material (action verbs), relational, verbal, and mental. They help writers further identify and characterize the participants while simultaneously allowing them to construct action sequences and paint an image of what the characters said, felt, and thought (Derewianka, 2004). Circumstances are realized through adverbs which "build up the material reality of the possible world" (Cheng, 2008, p. 172), "introduce information about manner, and express judgment about behavior" (Schleppegrell, 2004, p. 85).

Tenor, on the other hand, refers to the relationship the writer builds with the readers. To express these relationships, and also their opinions and attitudes (Fang & Schleppegrell, 2010), authors employ linguistic devices such as mood (interrogative, declarative, and imperative clauses), modality (modal adverbs and verbs that help express, inclination, probability, usuality, typicality, obviousness, obligation, and inclination), appraisal (expressions of affect, judgment, and appreciation) and graduation (expressions that increase force and blur or sharpen meanings (Butt et al., 2006). In narratives, authors utilize mood resources such as exclamatives, rhetorical questions, and quoted speech to create suspense (Cheng, 2008). Furthermore, they resort to imperatives and one-word sentences to construct more "poignant effects" on the readers (Knapp & Watkins, 2005, p. 222). Finally, they deploy a myriad of appraisal devices to move through the evaluative and reflective stages of their narratives, to enhance their meanings, and "to create images in the readers' minds" (Derewianka, 2004, p. 44).

Mode refers to how writers "weave meanings together into cohesive wholes" or "give texts their texture" (Butt et al., 2006, p. 210). To do this, they often use theme progression and textual, interpersonal, and topical themes. Theme progression refers to how authors pick up in the first part of each clause, or the theme, elements mentioned in the last part of the previous clause or rheme. It also refers to how they repeat "meanings from the theme of one clause in the theme of subsequent clauses" (Butt et al., 2006, p. 142). Textual, interpersonal, and topical themes are used to connect the message to the previous one (textual themes), to indicate the kind of interaction between speakers or the positions which they are taking (interpersonal themes), and to signal who or what is experiencing the process (topical themes) (Butt et al., 2006).

In narratives, authors usually take advantage of theme progression to mark that events are happening in a time sequence. In addition, they draw on textual themes or conjunctive devices of time and sequence (after, as, before, since, till, until, when, while), contrast (although, even though, though, whereas, while, rather than), consequence (in consequence, as a consequence, as a result, therefore, hence, for this reason, that is why, and thus), to achieve various purposes. These purposes may include signposting the unfolding of events, signaling the crisis point of the story, or indicating a return to normality. Moreover, they bring into play interpersonal themes (e.g., unfortunately, surprisingly) to indicate the way the writer is evaluating the events of the complication. Finally, they utilize marked circumstances as topical themes to set the story in a time and place (Butt et al., 2006).

Camilo's Narrative Unit

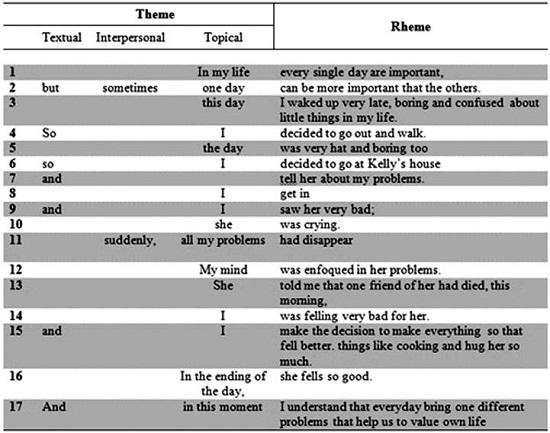

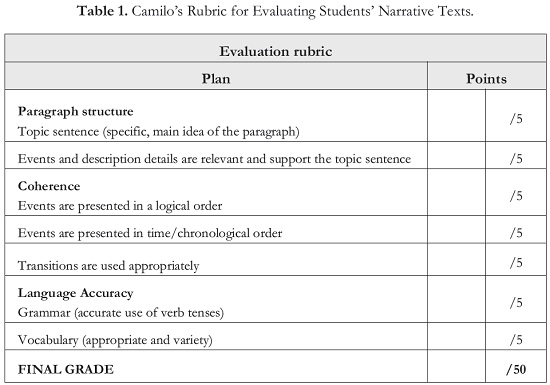

Camilo's narrative unit was taught as part of a Written Communication II course offered to students during the second semester of their EFL Teacher Education Program. The course, as one of its main objectives, had to familiarize students with reading techniques and to give them practice in writing informative, descriptive, narrative, and argumentative texts. Believing, as most product-based instructors do, that knowledge of grammar was a precondition for writing narratives, Camilo, a novice EFL writing instructor with no previous training in teaching writing, devised some exercises to practice tense forms and punctuation. Once this grammar preparation was over, he devised a series of prewriting activities based on the textbook Evergreen: A guide to writing with readings (Fawcett & Sandberg, 1996). These activities included the analysis of a narrative paragraph in terms of its structure and use of verb tenses, punctuationmarks, and cohesive devices such as transitional expressions, time markers, and repetition. They also included the pair writing of a narrative paragraph and the analysis of several of these paragraphs with the whole class based on the rubric shown in Table 1.

Finally, activities included an exam for which Camilo gave students two hours to complete. For this assessment activity, he asked students to individually write a 100 word narrative paragraph that followed the structure studied in class. As for the topic of the narrative, Camilo gave students four options: a favorite family story, a lesson about life, a story that ends with a surprise, or a triumphant or embarrassing moment. The criteria for assessment of this outline and narrative were the same used for the samples analyzed in class (see Table 1).

Ana's Narrative Text

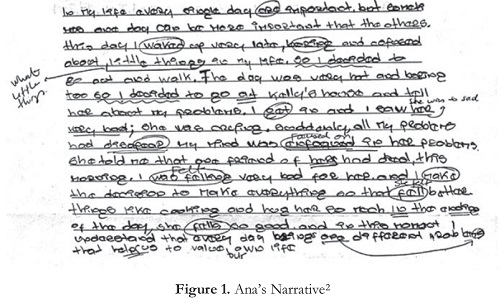

Ana1 was a 20-year-old student who was taking the course for the second time and was still struggling with the writing assignments proposed. She had entered the program after completing an associate degree in tourism. However, she claimed not to have studied English formally previous to her admittance into this program. From the four topic choices that Camilo gave students, Ana decided to choose the second option: a lesson about life (see Figure 1)2.

As can be seen in Figure 1, Camilo's initial analysis of Ana's text focused on how accurately she was using grammar features such as (a) verb conjugation (Lines 7, 9, and 11), (b) verb form (Line 3), (c) subject and verb agreement (Lines 1 and 16), (d) spelling (Lines 12 and 14), (e) number agreement (Line 15), (f) use of prepositions (Lines 6 and 13), and (g) the use of possessives (Lines 10 and 16). It did not focus on content or on meaning expansion and elaboration. Indeed, Camilo only made one suggestion on content by underlining the phrase "little things," which referred to Ana's situations in life, and by asking for more description of what those little things were (Line 4).

Analysis of Ana's Narrative Text in the Study Group

As explained earlier, once in the study group, Camilo analyzed Ana's narrative text at the field, tenor, and mode levels. As he did this, he came to the important realization not only as to how Ana had made use of experiential, interpersonal, and textual meanings but also as to how he could have better assisted her in producing a less informal, more academic, and also more elaborate and engaging narrative. In the following paragraphs, we present his analysis and realizations regarding each of these levels.

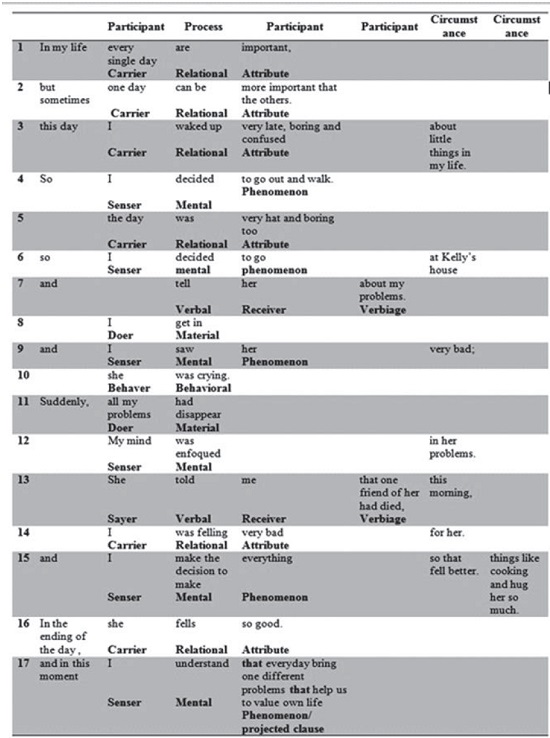

Analysis of Ana's text at the field level. As explained in the theoretical framework, to develop the topic of a text, or its field, writers make use of a series of linguistic resources available to them such as participants, processes, and circumstances. An analysis of Ana's narrative text at the field level allowed Camilo to realize that Ana could have made more effective use of these field resources. Her participants, for example, were not the individualized characters with defined identities and roles that narrative authors commonly create to develop their action sequences.On the contrary, they were rather simplistic and lacking all the force and colorfulness of most of the participants in narratives (see Appendix 1).

In effect, as can be seen in Figure 2, Ana, in her narrative, had incorporated five main participants: I (Clauses 3, 4, 6, 8, 9, 14, 15, and 17), the day (Clauses 1, 2, 5), she (Clauses 10, 13, and 16), all my problems (Clause 11), and my mind (Clause 12). To characterize them, she had scarcely employed any pre-modifiers, and these were regular adverbs, nouns, determiners, and possessives, as can be seen in clauses 1, 2, 5, 11, and 12.

(1) In my life every single day are important,

(2) but sometimes one day can be more important that the others.

(5) the day was very hat and boring too

(11) suddenly, all my problems had disappear.

(12) My mind was enfoqued in her problems [sic]

Similarly, Ana had employed very few post-modifiers and these were simple adjectives, not relative, participial, and infinitive clauses, or prepositional phrases as is characteristic of narratives. She had only included a comparative phrase (Clause 2), two participial phrases (Clause 3), and two adjectives pre-modified by the adverbs very and so (Clauses 5, 14, and 16).

(2) but sometimes one day can be more important that the others.

(3) this day I waked up very late, boring and confused about little things in life.

(5) the day was very hat and boring too

(14) I was felling very bad for her.

(16) In the ending of the day, she fells so good. [sic]

As Camilo saw this, he also realized he could have helped Ana better characterize and identify these participants by encouraging her to add some relative clauses (Clause 11). He could also have prompted her to add some chains of adjectives and adverbs (Clauses 12 and 14); and some participial and infinitive clauses (Clause 16), while at the same time making some small modifications to her tense use (Clause 14).

(11) suddenly, all the problems that were causing me pain up to that moment had disappeared.

(12) My previously tormented and restless mind.

(14) I felt anguished, distraught and extremely sad for her.

(16) She felt more calmed and willing to accept the difficulties that life brings.

As for the processes in Ana's narrative, Camilo came to see that these were also far from being the varied, forceful, and metaphorical ones that are common in narratives. In effect, although Ana had incorporated five mental processes (decided, saw, was enfoqued [sic], make the decision, and understand), only one was a verbal process (tell, in Clause 7), and this is repeated in Clause 13, modifying merely the tense (told). Also, Ana had barely included any material processes (get in and had disappear, Clauses 8 and 11). As a consequence, readers could have very little understanding of what the participants in her narrative actually said or did.

To expand Ana's repertoire of choices in terms of processes, Camilo realized that he could have asked her to think of and list other verbal processes that could provide not only more variety to her narrative but also a more metaphorical picture of what was being said, as can be seen in Clauses 7 and 13. In addition, he could have shown her how to incorporate dialogue in her narrative, as can be seen in Clause 13.

(7) and shared all my problems with her.

(13) She screamed to me in a hoarse voice, "My friend Alfredo died this morning."

Furthermore, he could have prompted her to think of how to introduce more action sequences in which she could paint a better picture of what exactly happened. For example, in her complication, he could have encouraged her to insert a few clauses such as the ones below, which better described what she cooked and what her friend did while she tried to make her feel better.

(*) I knew Kelly liked noodles,

(*) so, I went to the kitchen and searched for a package.

(*) I found it and cooked it with meatballs, lots of onions, and a half cup of Maggi broth.

(*) As I did this, Kelly talked about the last moments she had shared with her friend.

(*) When she described those moments, her voice sounded calmer, her breathing became even, and her eyes brightened up.

Finally, Camilo also came to understand he could have assisted Ana in making more effective use of circumstances. Indeed, she had introduced only one circumstance of matter (Clause 3), two of location (Clauses 6 and 13), one of manner (Clause 9), and one of cause (Clause 15), which left the reader with more questions than answers in regard to where, when, how, and why events had happened. Camilo could have helped her exploit this useful resource by showing her how not only to insert new circumstances but to expand upon the ones she had. For example, in Clauses 4, 8, and 10, Ana could have inserted a few more circumstances of extent (Clause 4), location (Clause 8), and manner (Clause 10).

(4) I decided to go out and walk for a while at a nearby public park.

(8) I get in a little before lunch.

(10) She was crying loudly as if something terrible had happened to her.

Also, in Clauses 6, 12, and 13, she could have expanded the circumstances she had to provide a better representation of where, how, and when events had taken place.

(6) so I decided to go to my friend Kelly's house where my soul knew it would find comfort.

(12) My mind was enfoqued in how to help her overcome her sadness and recover her liveliness.

(13) She told me that one friend of her had died that same seemingly bright but truly awful morning. [sic]

In sum, had Camilo had a deeper knowledge of how to effectively use experiential resources to construct narratives, he could have better assisted Ana in achieving the purpose of her narrative, that is, to describe the events that took place on one particular day. Additionally, he could have provided better help to Ana in writing a significantly richer narrative in which she presented a more detailed picture of the events that had happened that day, the people involved, and the circumstances under which these events had taken place. Consequently, Ana probably could have been better positioned to help her future EFL students write effective narratives.

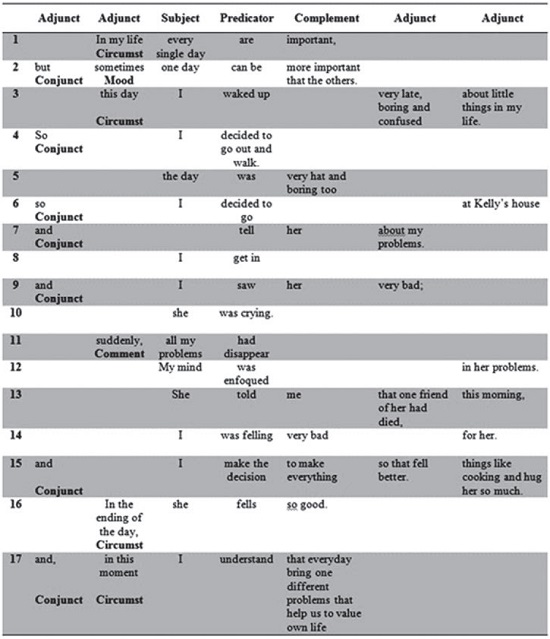

Analysis of Ana's text at the tenor level. As was explained previously, to build a relationship with the reader and to express their affect, judgment, and appreciation towards the events and characters in their texts, writers employ resources such as mood, modality, and appraisal. An analysis of these devices in Ana's text revealed to Camilo that, as with field, Ana could have made a more effective use of these resources in the construction of her narrative. In regard to mood, for instance, Ana had not included any exclamatives, rhetorical questions, quoted speech, imperatives, or one-word sentences in her text, as is common in narratives. She had only constructed declarative clauses, most of which were simple, containing only a subject, and a predicator (e.g., I get in); or a subject, a predicator, and a complement (e.g., the day was very hat and boring too), or a subject, a predicator, a complement, and an adjunct (e.g., I was felling very bad for her [sic]) (see Appendix 2).

To help her make more effective use of mood devices, Camilo could have advised Ana to incorporate some clauses, such as the ones below, in which the characters questioned themselves or others, and in which some rhetorical questions, exclamatives, and quoted speech were included.

(*) Who hasn't, at some point in their lives, experienced the death of a beloved one? Death is everywhere!

(*) She said, "My friend Alfredo died this morning! Can you imagine? Alfredo, the person most full of life I had ever known!" "Oh, God, no!" I heard myself saying.

(*) As I hugged her, I softly mumbled, "Cry my dear! Tears are good for the soul!"

As Camilo progressed with the analysis of tenor in Ana's narrative, he realized that she could also have made more appropriate use of appraisal devices. Indeed, Ana had included very few expressions of affection or emotion: boring and confused (Clause 3), very bad (Clause 14), better (Clause 15), and so good (Clause 16). She had also incorporated only one expression of judgment: very bad (Clause 9). Moreover, she had utilized scarcely three expressions of appreciation: important (Clauses 1 and 2), little things (Clause 3), and very hat and boring too [sic] (Clause 5).

Perhaps Camilo could have assisted Ana by analyzing with her where and how she could have provided more information both about the characters and events populating her narrative, and about her feelings and thoughts towards them. To illustrate, after Clause 3, Ana could have provided more information about both the little things tormenting her and how she felt about them. She could have written the following:

(*) The previous night, I had heard that my usually stoic and equanimous mother had decided to separate from my beloved but apparently cheating father because she could no longer stand his disrespect and lack of consideration towards her.

Also, in Clause 9, Ana had stated that her friend looked bad but her only explanation for this was that she was crying. She could have further explained why she thought her friend looked bad by adding some remarks about where she found Kelly, her physical condition at the time she saw her, and/or Kelly's emotional state. To do this, she could have written as follows:

(*) She was lying in bed still in her pajamas with two blankets on.

(*) Her eyes were red with deep black circles around them, and somber looking.

(*) She seemed anguished, distraught, and extremely sad.

Besides, Ana had stated that her friend had died. However, she had not provided many details about her friend or the circumstances in which this had happened. She could have offered a clearer picture not only of this event but of Kelly's feelings toward him by inserting a few clauses such as the following:

(*) She mumbled, "He had a terrible accident."

(*) His car crashed strepitously into another before going off a cliff.

(*) I don't know what I will do. He was my heart and soul, so kind and patient all the time, and always so willing to help."

Finally, Ana's predicators, or verbs, lacked the force that is typical of these linguistic devices in narratives. In effect, her simple predicators provided readers with a very partial image of how exactly she got in the house, how her friend had told her about her misfortune, or how hard her friend was crying.

To provide more support to Ana with the use of predicators, Camilo understood he could have instructed her to think of synonyms for those she had used in her narrative (e.g., get in, was crying and told). He could also have pointed out to her the nuances in meaning that were achieved by using synonyms such as drag myself in, was sobbing, and shouted, which not only described the action but also the manner in which the events had happened (e.g., with difficulty, in a noisy way, very loudly), to wit:

(8) I dragged myself in.

(10) she was sobbing.

(13) She shouted, "My friend Alfredo died this morning."

In sum, had Camilo had a deeper understanding of how writers deploy interpersonal resources such as mood, modality, and appraisal to interact with the audience, to sneakily appeal to their feelings and to help them transport themselves to a specific moment and place, he would have been better able to help Ana write more appealing and involving narratives. Moreover, he probably would have been better prepared to guide Ana as to how to help her future EFL students write engaging texts that readers would want to read to the end.

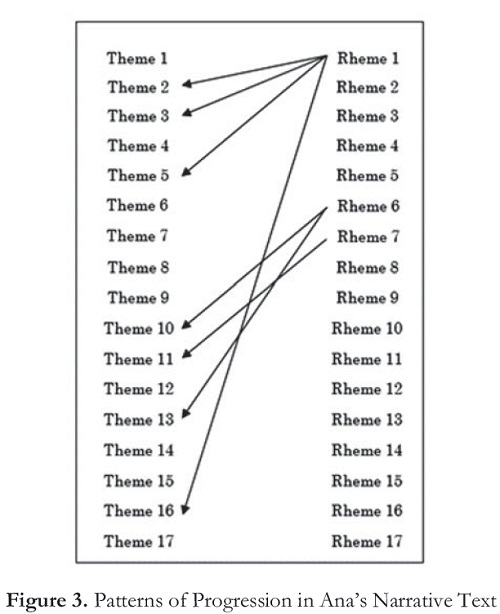

Analysis of Ana's text at the mode level. As explained in the theoretical framework, writers use theme-rheme progression, and textual, interpersonal, and topical themes to weave meanings together and to create a cohesive whole. As Camilo analyzed Ana's theme progression, he realized this could have better facilitated the reader's task of following the participants and processes introduced in the text. Indeed, although in her themes Ana had picked up on elements of her previous themes and rhemes (see Figure 3), her themes had not been very elaborate and had provided little information about the participants and processes introduced in the rhemes of the previous clauses (see Appendix 3).

As a consequence, the reader had been left wondering about the details of many of the participants (little things in my life, Kelly's house, her problems, one friend, and everything) and processes (decided to go out and walk, decided to go to Kelly's house, get in, saw her very bad, was feeling bad for her, and cooking and hugging). What were these little things? Where is Kelly's house? What were Ana's problems? Who was this friend? Why walk? Where did she go? How did she get in? Why to Kelly's house? Why did she look bad? Why did Ana feel bad for Kelly? What did she cook? How long did they hug? These are all questions that emerge from Ana's text that could have been answered in the rheme part of her clauses but are left unanswered.

To help Ana improve her themes, Camilo realized he could have advised her to think of ways in which the nouns and processes introduced in her rhemes could be elaborated on in her themes instead of being left aside, as shown below:

(4) These things concerned my mother and my father, specifically and the...

(7) Her place was just a few minutes away from my house...

(12) These were seemingly worse than mine...

Other mode devices that Ana could have more aptly employed were textual, interpersonal, and topical themes. Indeed, an analysis of Ana's textual themes showed Camilo that Ana had not used any time or sequence conjunctions in her narrative, in spite of the fact that narratives are characterized first and foremost by presenting a series of events in a time sequence. Instead, Ana had included the coordinating conjunction and four times in Clauses 7, 9, 15, and 17. This had created the feeling of an oral as opposed to a written narrative, and had done little in the way of guiding readers through the time sequence of the narrative. Also, although Ana had written one contrast conjunction (but) and a consequence conjunction (so), she had incorporated these in the most unlikely places. In effect, she had injected but in Clause 2 as part of her abstract when in narratives this conjunction usually appears in the complication that signals the crisis point of the story. Besides, she had inserted so in Clauses 4 and 6 as part of her orientation when, in narratives, this is normally found in the resolution "to signal a return to normality" (Butt et al. 2006, p. 154).

To contribute to Ana's more effective use of textual themes, Camilo realized he could have reviewed with her the different conjunctions that are available to narrative authors to establish time, sequence, contrast, and consequence. Additionally, he could have examined with her the stages of the narrative in which each of these devices were likely to be found. Next, he could have assisted her in choosing the ones that could have better signposted the events in her narrative such as the following:

(4) Soon after that, I decide to go out and walk.

(8) When I got in,

(16) As a consequence, in the ending of the day, she fell so good.

As for Ana's interpersonal themes, an analysis of these showed Camilo that Ana could also have made a more extensive use of these, allowing readers to have a clearer view of her evaluation of the events presented in her narrative and of their relevance. Indeed, Ana barely used two interpersonal themes: sometimes (Clause 2), and suddenly (Clause 11).

To facilitate Ana's understanding of interpersonal themes, Camilo could have suggested others such as usual, surprisingly, and evidently, which she could have distributed throughout the text to better set the stage for the events to be described.

(6) As usual, I decided to go at Kelly's house

(9) Surprisingly, I saw her very bad

(12) Evidently, my mind was enfoqued in her problems [sic]

As for Ana's use of topical themes, Camilo realized that these did not really allow her to mark a progression in time, as is common in narrative writing. Indeed, her topical themes can be summarized as follows:

Participants: one day, the day, I (x6), she (x2), all my problems, my mind

Circumstances: in my life, this day, in the ending of the day, and in this moment

This analysis shows that Ana had mainly been concerned with herself as an actor, not with the events that had taken place or with the sequencing of these events, as the lack of processes, or nominalized processes (e.g., the walk, her crying, the cooking) in this topical position suggests. Besides, even though in her topical themes she had made use of some marked circumstances of location such as in my life, this day, in the ending of the day and in this moment, these had not really built a progression in time.

To better guide Ana in her use of topical themes, Camilo realized he could have made a list with her of all of the participants and circumstances in her topical theme position and asked her to think of ways in which she could have better exploited this position in order to follow the events that took place on that day and the sequence in which they occurred. This way, the reader could have more easily followed the thread of the narrative. Here are four examples:

(*) The walk turned out to be less pleasant than I had planned.

(8) Twenty minutes later, I get in.

(*) Her crying was desperate.

(15) Before the afternoon gave room to the night, I make the decision to...

In sum, had Camilo had a better grasp of how narrative writers can use textual resources, theme progression, and textual, interpersonal, and topical themes to create a tapestry of meanings, he could have more proficiently helped Ana do the following: (a) write a cohesive text in which readers could have found tighter connections between clauses, (b) think of ways in which the events of that day would sound less repetitive and monotonous and more cohesive and entertaining, and (c) help her future students become "aware of the choices they have for thematic structure and the meanings that different thematic choices convey" (Schleppegrell, 1998, p. 206).

Discussion and Conclusions

By presenting the insights that Camilo, a novice EFL writing instructor, gained from the SFL analysis of the narrative that one of the students in his course had produced, we intended for this article to contribute to the conversation about what approaches could be most useful in helping university students, particularly EFL pre-service teachers, write the type of academic texts that they need to write during the course of their academic programs.

Even though there are many other approaches that can either be used individually or combined with SFL to help university students improve their writing, the analysis presented here shows the tremendous writing possibilities that open up for instructors when they are knowledgeable of SFL theories and approaches; that is, when they are aware of the experiential, interpersonal, and textual resources that are commonly deployed by effective writers of the genres they are teaching.

The analysis also demonstrates that despite the fact that narratives seem to be one of the genres that present the least difficulty to students, their teaching needs to be carefully planned for at least two reasons: First, effective academic narratives are not as easily constructed as it would seem. They require extensive vocabulary and ample knowledge of the experiential, interpersonal, and textual resources that narrative writers in that particular culture deploy when producing narrative texts, a clear understanding of the context, situation and audience, and an awareness of the differences between oral and written modes. Second, as referred to by Knapp and Watkins (2005), they appear in most of the macro-genres that we ask students to produce during their programs of study, namely, research reports, information reports, and essays. As such, they need to be conferred as much importance as other genres.

Finally, the analysis presented here proves the importance of creating study groups, such as the one described here, in which EFL writing instructors have a space to not only expand their knowledge of the structure of the genres that they will be teaching but also of how they can use that knowledge to support EFL students' writing. As Schleppegrell (1998) claims, teachers need explicit knowledge of the particular lexical, grammatical, and textual features of the academic genres that students are asked to produce (Schleppegrell 1998) "and a metalanguage to make that knowledge accessible to their students" (Achugar, Schleppegrell, & Oteíza, 2007, p. 21). They also need spaces where they can "think about the assignments they give in new ways [and where they can become] more aware of the linguistic challenges of the tasks they assign" (Schleppegrell, 1998, p. 209).

Spaces such as these should be provided by universities. Programs cannot expect that the EFL writing instructors who are hired have this knowledge or that they quickly develop it by themselves without participation in professional development programs that allow them to develop it. Although this type of programs can imply a great investment for universities, the efforts are worth it. EFL programs, and EFL teacher preparation programs in particular, cannot continue to ignore their responsibility in offering professional development to the instructors they hire. Neither can they afford to graduate students, particularly EFL teachers, who cannot write the academic texts that they are required to write in their advanced courses or after graduation. If indeed it is true that the ability to write academic texts "may not automatically or always translate into future economic gains and political power for students" (Luke as cited in Fang et al., 2006, p. 251), it is also true that it may increase students' possibilities for "access to education at higher levels [and expand] the range of opportunities outside of school" (Fang et al., 2006, p. 250).

For EFL pre-service teachers such as Ana, the need for this type of knowledge is even stronger since they will be the ones in charge of helping prospective university students to adopt a different view of texts as purposeful and situated. Furthermore, they will be the ones responsible for apprenticing students as to how to become text analysts, and for interrupting the cycle of frustration that now has EFL university instructors blaming students, students blaming EFL school teachers, EFL school teachers blaming EFL teacher preparation programs, and directors of EFL teacher preparation programs blaming students. The experience with Camilo and the study group suggests that the study of SFL theories through study groups will allow EFL writing instructors to make that shift in views and pedagogical practices, and hopefully stop this cycle.

However, more research is needed to document how a systematic study of SFL theories by EFL writing instructors attending study groups not only translates into changes in classroom practice but also improves EFL students' understanding and production of academic genres, such as narratives, both across and outside university courses. Studies are also needed on how EFL pre-service teachers receiving this type of instruction put this knowledge into practice in the school and university settings where they work, and on whether these practices actually position them to better assist their prospective students with the writing of academic genres. Although there is documentation as to the success of this approach in several parts of the globe, particularly in Australia and the US (see most authors cited above), little is known about its real usefulness in EFL settings such as ours.

1A pseudonym has been used to protect the student's identity.

2The figure shows a copy of Ana's narrative paragraph in her handwriting, with Camilo's scribbles on top.

References

Achugar, M., Schleppegrell, M. J., & Oteíza, T. (2007). Engaging teachers in language analysis: A functional linguistics approach to reflective literacy. English Teaching: Practice and Critique, 6(2), 8-24. [ Links ]

Artunduaga Cuéllar, M. T. (2013). Process writing and the development of grammatical competence. HOW, A Colombian Journal for Teachers of English, 20(1), 11-35. [ Links ]

Butt, D., Fahey, R., Feez, S., Spinks, S., & Yallop, C. (2006). Using functional grammar: An explorer's guide. National Center for English language Teaching and Research, Sydney, AU: Macquarie University. [ Links ]

Cárdenas, M. L., Nieto, M. C., & Martin, Y. M. (2005). Conditions for monograph projects by preservice teachers: Lessons from the long and winding route. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 7, 75-94. [ Links ]

Cárdenas, M. L., Nieto, M. C., Bellanger, V., Cortés, L., & Ruger, A. (2005). La problemática de los trabajos monográficos en un programa de licenciatura en idiomas: Análisis y perspectivas [Problems in monographs from an undergraduate program in languages: Analysis and perspectives]. Ikala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 10(16), 315-342. [ Links ]

Chala, P. A., & Chapetón, C. M. (2013). The role of genre-based activities in the writing of argumentative essays in EFL. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 15(2), 127-147. [ Links ]

Chapetón, C. M., & Chala, P. A. (2013). Undertaking the act of writing as a situated social practice: Going beyond the linguistic and the textual. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 15(1), 25-42. http://dx.doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2013.1.a02. [ Links ]

Cheng, F. W. (2008). Scaffolding language, scaffolding writing: A genre approach to teaching narrative writing. The Asian EFL Journal, 10(2), 167-191. [ Links ]

Derewianka, B. (2004). Exploring how texts work. Newtown, AU: Primary English Teaching Association. [ Links ]

Eggins, S. (2004). An introduction to systemic functional linguistics. London, UK: Continuum. [ Links ]

Fang, Z., & Schleppegrell, M. J. (2010). Disciplinary literacies across content areas: Supporting secondary reading through functional language analysis. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 53(7), 587-597. http://dx.doi.org/10.1598/JAAL.53.7.6. [ Links ]

Fang, Z., Schleppegrell, M. J., & Cox, B. E. (2006). Understanding the language demands of schooling: Nouns in academic registers. Journal of Literacy Research, 38(3), 247-273. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15548430jlr3803_1. [ Links ]

Fawcett, S., & Sandberg, A. (1996). Evergreen: A guide to writing with readings. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company. [ Links ]

Halliday, M. A. K. (1978). Language as social semiotic: The social interpretation of language and meaning. London, UK: Edward Arnold. [ Links ]

Knapp, P., & Watkins, M. (2005). Genre, text, grammar: Technologies for teaching and assessing writing. Sydney, AU: University of New South Wales Press. [ Links ]

Rivera Barreto, A. M. (2011). Improving writing through stages. HOW, A Colombian Journal for Teachers of English, 18(1), 11-23. [ Links ]

Robayo Luna, A. M., & Hernandez Ortiz, L. S. (2013). Collaborative writing to enhance academic writing development through project work. HOW, A Colombian Journal for Teachers of English, 20(1), 130-148. [ Links ]

Schleppegrell, M. J. (1998). Grammar as resource: Writing a description. Research in the Teaching of English, 32(2), 182-211. [ Links ]

Schleppegrell, M. J. (2004). The language of schooling: A functional linguistics perspective. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Thompson, G. (2004). Introducing functional grammar (2nd ed.). London, UK: Arnold. [ Links ]

Zúñiga, G., & Macías, D. F. (2006). Refining students' academic writing skills in an undergraduate foreign language teaching program. Ikala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 11(17), 311-336. [ Links ]

The Authors

Doris Correa holds a Doctorate degree in Language, Literacy, and Culture from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Currently, she works as an Associate Professor at the School of Languages, Universidad de Antioquia (Colombia), where she has done research in English language policy, critical literacies, systemic functional linguistics, and linguistic landscapes.

Camilo Domínguez is currently pursuing a Master's degree in Foreign Language Teaching and Learning at Universidad de Antioquia (Medellín, Colombia), where he currently works as an EFL instructor. He is a member of the GIAE Research Group and has done research in areas such as critical literacies and linguistic landscapes.

Appendix 1: Field Analysis of Ana's Text

Appendix 2: Tenor Analysis of Ana's Text

Appendix 3: Mode Analysis of Ana's Text