Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

How

Print version ISSN 0120-5927

How vol.22 no.1 Bogotá Jan./June 2015

https://doi.org/10.19183/how.22.1.133

http://dx.doi.org/10.19183/how.22.1.133

Analysis of the Teaching Practices at a Colombian Foreign Language Institute and Their Effects on Students' Communicative Competence

Análisis de las prácticas pedagógicas en un instituto de lenguas extranjeras colombiano y sus efectos en la competencia comunicativa de los estudiantes

María Fernanda Jaime Osorioa

Edgar Alirio Insuastyb

aUniversidad Surcolombiana, Neiva, Colombia. E-mail: mafejaos84@gmail.com.

bUniversidad Surcolombiana, Neiva, Colombia. E-mail: edalin@usco.edu.co.

Received: July 31, 2014. Accepted: February 11, 2015.

How to cite this article (APA 6th ed.):

Jaime Osorio, M. F., & Insuasty, E. A. (2015). Analysis of the teaching practices at a Colombian foreign language institute and their effects on students' communicative competence. HOW, 22(1), 45-64. http://dx.doi.org/10.19183/how.22.1.133.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. License Deed can be consulted at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

This research report is an account of a study carried out at the Foreign Language Institute of a Colombian public university. Its main purposes were to analyze the teaching practices the participating teachers used in their English lessons, and to assess the effects of these practices on the development of students' communicative competence. A qualitative-descriptive methodology was followed by means of lesson observations and semi-structured interviews. A quantitative data analysis of test results was also undertaken to measure the development of students' communicative competence. Pre-communicative teaching practices were found to be more frequent than communicative ones. Likewise, certain aspects of the students' organizational and pragmatic competences were also enhanced.

Key words: Communicative activities, communicative competence, English as a foreign language, pre-communicative activities, teaching practices.

Este reporte investigativo da cuenta de un estudio realizado en el instituto de lenguas extranjeras de una universidad pública colombiana. Sus objetivos principales fueron analizar las prácticas pedagógicas de los docentes participantes y evaluar sus efectos en el desarrollo de la competencia comunicativa de los estudiantes. Se siguió una metodología cualitativa descriptiva mediante observaciones de clases, tests y entrevistas semiestructuradas. Igualmente, se hizo un análisis cuantitativo de los resultados de tests utilizados para medir el desarrollo de la competencia comunicativa de los estudiantes. Se encontró que las prácticas pre-comunicativas son más frecuentes que las comunicativas. Asímismo, se resaltan ciertos aspectos de las competencias organizacional y pragmática de los estudiantes.

Palabras clave: actividades comunicativas, actividades pre-co municativas, competencia comunicativa, inglés como lengua extranjera, prácticas pedagógicas.

Introduction

In response to the widespread need of strengthening the teaching and learning process of foreign languages in the South Colombian region as well as conducting research in this professional field, the Instituto de Lenguas Extranjeras de la Universidad Surcolombiana (ILEUSCO) was officially created by the Higher University Council of Universidad Surcolombiana in 2006. This institute started offering English courses in 2008 with the commitment of developing the students' communicative competence at an upper-intermediate level. To this effect, a curriculum made of eleven levels with a length of 770 hours was designed. However, it has been established through anecdotal evidence that not every student who reaches the last level achieves the desired proficiency level.

In search for possible explanations to this situation, the research group ILESEARCH conducted this study aimed at analyzing the teaching practices used by the teachers and at assessing the effects of these practices on the learning process of the students.

The topic of teaching practices has already been explored in other educational settings. For example, Zúñiga Camacho, Insuasty, Macías Villegas, Zambrano Castillo, and Guzmán Durán (2009) carried out research to identify:

The teaching practices used by the English teachers working in the courses taken by undergraduate students at Universidad Surcolombiana. [Its main finding was] that pre-communicative practices aimed at developing linguistic competence were prevalent among the teachers taking part in the study. (p. 11)

Insuasty and Zambrano (2014) stated in an unpublished document that high school English teachers performed structural or quasi-communicative instructional activities rather than functional or social ones.

Even though these studies dealt with the notion of teaching practice not only as the observable behavior of the teacher in class but also as his or her system of beliefs, they failed to explore more deeply the way these teachers conceptualized their work; this being an important aspect for exploring change and improvement alternatives.

Therefore, this research analyzes the teaching practices of ILEUSCO faculty by taking into account what the teachers think, what they do in the classroom, and the outcomes they generate.

Theoretical Framework

In this section, general notions about teaching practices are first discussed. Next, the teaching practices of English teachers, which are aimed at developing students' communicative competences, are examined. From a broad perspective, these practices are concerned with the basic psychological and linguistics principles English teachers are inspired by, the features of the communicative goal they pursue, the continuum of practical activities which they can rely on, and the sort of roles both teachers and learners play in the teaching and learning process.

Teaching Practices

The so-called notion of teaching practices has been characterized and defined by many scholars who have remarkably nourished its concept. Flórez Ochoa (1994), for example, defined teaching practice as the intentional and planned process to facilitate in certain individuals the appropriateness of some portion of knowledge in order to contribute to the development of their careers. Moreover, Tamayo Valencia (2002) argued that teaching practice is not simply understood as teaching contents and transmitting information, although often it seems so, but that it implicitly or explicitly comprises a complex event: It is a methodological notion that designates both theoretical and practical pedagogical models used in the different levels of education. In other words, teaching practice is the professional work of a teacher in the classroom, supported by different beliefs, research, theories, and models.

Teaching practices were also called complex by Malderez and Bodóczky (1999). They described them as a dynamic interplay of practice and theory. Teachers' professional behavior and subject knowledge is just “the tip of the iceberg” (see Figure 1). They explained that below the surface there are processes the teacher “goes through” before acting in the classroom. For example, planning and reviewing, and selecting and/or learning are the processes just below the surface; but deeper, the teacher is influenced by knowledge about students, language form and usage, activities, and process skills. All the same, those constructs are “embedded” in their concepts of education, teaching, learning, professionalism, and others that “have been previously influenced by even more fundamental beliefs, attitudes, and experiences” (Malderez & Bodóczky, 1999, p. 14).

Teaching Practices for Communicative Competence Development

In keeping with the general notion of teaching practice, the English teacher is also expected to carry out practical tasks in the classroom which are informed by some psychological or linguistic principles with the purpose of facilitating students' development of communicative competence in the target language.

As a matter of fact, in recent decades, the particular field of teaching English as a foreign language (TEFL) has promoted a wide diversity of pedagogical practices to develop students' communicative competence, the communicative approaches being the most prevalent. Some principles of learning underlying these approaches are as follows: (1) According to the theory of meaningful learning by Ausubel (1963), learning happens through a significant process of relating new concepts consistent with the knowledge that the learner has previously acquired; (2) The main reason for learning a language is the existence of a communicative necessity which makes students feel they are learning to do something useful with the second language; (3) The success of communicative language learning depends on the quality of opportunities that the student is given to use the language; (4) The existence of a socio-humanistic environment, driven by a facilitator teacher, allows the learner to express him/herself without restrictions; (5) The input (or linguistic material to which the student is exposed) should be understandable, relevant to the immediate interests, neither too complex nor strictly graduated. It should be an interesting way to help create a relaxed atmosphere in the classroom; (6) The interaction that involves negotiation of meaning makes the process of acquiring a second language easier.

To measure the structure of the communicative competence, we will briefly summarize two of the most discussed proposals in the field of the second language pedagogy, the models established by Canale and Swain (1980) and Bachman (1990).

Canale and Swain (1980) note that the construct of communicative competence consists of four basic components: The grammatical competence, which refers to the degree of domain of the linguistic code; the sociolinguistic competence, that has to do with the ability to produce appropriate statements in form and meaning in any communicative situation, which assumes knowledge of sociocultural rules of language; the discourse competence, that requires ability to connect sentences in communicative situations using markers of cohesion and coherence; and the strategic competence, which reflects the potential to use any linguistic or paralinguistic resource so that communication continues to develop.

On the other hand, Bachman (1990) proposed an alternative model for understanding the communicative competence which consists of three components: language competence, strategic competence, and psychophysiological mechanisms.

Competence in the language is described as knowledge of the language and its components, and includes two types of skills: organizational competence and pragmatic competence. First, the organizational competence refers to the domain of the formal structure of language (grammatical competence), vocabulary, syntax, and phonemic and graphic elements. It also refers to the construction of discourse (textual competence) that considers the cohesion and rhetorical organization. Second, the pragmatic competence or functional use of language (illocutionary competence) controls the functional features of language: ideational functions to express ideas and emotions; manipulative functions to make something happen; heuristic functions for teaching, learning, and problem solving; and imaginative functions to be creative. Finally, the sociolinguistic competence refers to the sensitivity towards different dialects and registers, as well as the understanding of language and cultural referents.

The strategic competence develops as an integrating component of interrelationships between knowledge of the world with language, and the psychophysiological mechanisms and context. The strategic competence is not only used as a form of compensation but also as a communication strategy to ensure the effectiveness of it, to overcome impasses and the way we manipulate language in order to achieve the purposes of communication. The psychophysiological mechanisms involved in communicative proficiency comprise two types of skills: productive (oral and visual) and receptive (aural and visual).

Pre-Communicative and Communicative Activities

The development of communicative competence involves the acquisition and use of so-called language skills, which are promoted from the communicative approach in an integrated manner and with real communication purposes. To contribute to the development of these communicative language skills, the English teacher has a continuum of options ranging from so-called pre-communicative activities to proper communication activities. According to Littlewood (1998), the first are based on accuracy and present structures, functions, and vocabulary; the latter focus on fluency and involve information sharing and exchange.

The pre-communicative activities are subdivided into structural activities and quasi-communicative activities. Structural activities are described as machining and practical structures. The quasi-communicative ones are based on communication and the structure of the language.

Among the pre or quasi communicative activities we find the following: answering questions, complete discussions, true and false exercises, reading aloud, guided conversations, dictation, classification of information, dialogues, songs, writing questions, scrambled sentences, scrambled paragraphs, and information transfer.

Simultaneously, the communicative activities are subdivided into functional activities and social interaction activities. In functional communication activities, interaction becomes less controlled by artificial conventions and, in turn, meanings that learners need to express become less predictable. There is also a growing opportunity for learners to express their own individuality in the discussions. The teacher illustrates structures so that learners have to fill a void of information or solve a problem. The functional communication activities are divided basically into four groups: (a) sharing information with restricted cooperation—when a learner (or group) has information that another learner (or group) must discover; (b) sharing information with full cooperation: Instead of just asking and answering questions, learners can now use the language to describe, suggest, ask for clarification and cooperate with each other; (c) sharing and processing information: Apprentices must not only share information, but also discuss and evaluate it in order to solve a problem; (d) processing information: The stimuli for communication come from the need to discuss and evaluate in pairs or groups the facts known by the interlocutors to solve a problem or propose a solution.

The activities of social interaction add a more clearly defined social context to the dimension of functional activities. Littlewood's most significant features are: (1) Apprentices must pay greater attention to functional and social meanings that language conveys; (2) These activities more closely approximate the kind of communication that happens outside the classroom; (3) Learners should try to communicate in a way that is not merely functional, but fits the social conventions governing communication between friends or greater degree of formality; (4) Students usually do not need encouragement to communicate since they automatically engage their social role; (5) From their mother tongue, learners know that all speech is both functional containing social implications and must ultimately ensure social acceptability as the functional effectiveness; (6) There are many ways teachers can prepare students for communication in various social contexts in which they will have to act outside the classroom; (7) Within the activities of social interaction, classroom discussion is also presented as a social context. The classroom is itself a real social context where learners and teachers also enter real social situations. The most common activities within social interaction techniques are simulation and role play.

In conclusion, the teacher should consider the following factors when choosing the type of activity for social interaction:

- The teacher should correlate the language requirements of an activity as closely as possible with the linguistic capabilities of the apprentices.

- Note that the structures and functions are not subject to specific situations.

- The teacher should ensure maximum efficiency and economy in student learning.

- The situations should be able to encourage learners to a high degree of communicative engagement.

- Students' role play should have some margin of occurrence in real life.

The development of communicative activities in the classroom also implies that teachers and learners assume certain roles. Richards and Rodgers (2004) note that one of the teacher's roles is that of facilitator, which promotes interaction and communication among all participants. During the activities the teacher acts as a counselor, answering questions from students and monitoring their performance (Larsen-Freeman, 2007). Vanegas Rubio and Zambrano Castillo (1997) consider that to be a real facilitator the teacher should do several things: to expose students to a significant input, choose appropriate materials that promote interaction, generate an atmosphere of interesting and enjoyable learning, and promote independent learning, among others.

Another role is communicator, or participant suggested by Harmer (2007). The communicator teacher is sometimes expected to get actively involved in tasks that promote interaction among students, such as debates (with no control over the activity). The role of counsellor implies, according to Larsen-Freeman (2007), the teacher providing feedback from the strengths and weaknesses of students in the development of communicative competence.

Regarding the role of the learner, Bastidas Arteaga (1993) states that students must play an active role and be responsible for their own learning: “The student must go slowly becoming independent in their search for new knowledge” (p. 173). Larsen-Freeman (2007) add that the apprentice must become a negotiator of meanings to understand their partners and make themselves understood, adding that the student should primarily be a communicator. Finally, Richards and Rodgers (2004) stated the apprentice must be a negotiator between the learning process and the object of study.

Research Design

As an exploratory descriptive study the research design intended to characterize the pedagogical practices used by teachers of the institute of foreign language ILEUSCO in their English classes. Such pedagogical practices were classified under the light of the criteria exposed by Littlewood (1998) where it is argued that communicative language teaching comprises two types of activities: pre-communicative activities and communicative activities.

The data collection was also carried out through a cross-sectional design which, according to Cohen, Manion, and Morrison (2007), aims to provide a single “snapshot” to research the incidence of the modes of one or more variables in a population. The nature of this study wanted to measure the possible effects of teachers' practices in their students' communicative competence development; therefore, the snapshot taken from tests provided us with data for retrospective and prospective enquiries.

Participants

From a population of 34 teachers who provide professional services to ILEUSCO, nine of them actively participated in this study. The choice resulted from discretionary sampling, based on signing a consent form by those who decided to collaborate. Teachers were classified according to their English course level. All of the teachers are graduates holding bachelors degrees in elementary education with an emphasis in humanities and foreign language—English—from Universidad Surcolombiana.

Instruments for Data Collection

The instruments for data collection were as follows:

Lesson observation. Each of the nine teachers was observed for eight classes continuously. These observations were carried out by either one of the principal investigators, co-investigators, or research assistants. For registration information, the class was videotaped plus the materials and the type of activities developed through information and communication technologies (ICTs) were recorded by filling out a form. Simultaneously, to tape record the lesson, the observer filled out a form of focused observation.

Semi-structured interview. The questions for the interview (see Appendix) were planned to gather information on the views of the participating teachers about communicative competence and the way they develop their pedagogical practices in English classes. Each participant was interviewed and videotaped.

Tests. In order to assess the previous knowledge of students before starting each course, they were administered a pre-test. At the end of the course, students took a post-test to assess their progress in the development of communicative competence. Both the pre-test and post-test sections were structured to assess all four language skills (listening, speaking, reading, and writing), the components of language (structures, vocabulary, and pronunciation) and pragmatic organizational skills.

Procedure

Prior to data collection, the project was explained to the teachers and they were invited to participate. Nine teachers out of 34 were selected. Then the participants were interviewed and videotaped. During the second week of classes, students took the pre-test. Afterward, eight hours of classroom observation were carried out to characterize the pedagogical practices that teachers were implementing. Finally, the post-test was conducted.

Once the information was collected, it was analysed and classified. The data obtained from the semi-structured interviews were first analyzed and classified. Then, the pedagogical practices were distinguished among those who promoted the functional use of English and those who focused too much on the development of linguistic competence. A comparison and contrast of the tests results were completed. Previous results were presented to each one of the participating teachers, who reflected and presented their opinions about the results and possible future actions to be taken to improve them. Their voices were included in the general discussion section of this article.

Analysis of Information

The project was conceived from both qualitative and quantitative methods. By using both methods, we could establish a possible cause-effect relationship between teachers' practices and students' tests results. All the same, fixed information from the surveys helped us to understand possible cause-effect relationships between teachers' beliefs and their practices in the classroom. Schutt (2012) affirms that “qualitative data can provide information about the quality of standardized case records and quantitative survey measures, as well as offer some insight into the meaning of particular fixed responses” (p. 348). Therefore, quantified data provided us with information to compare and contrast beliefs, practices, and effects.

To organize and present the collected data, Cohen et al. (2007) exposed five possible ways: by groups, by individuals, by issue, by research question, and by instrument. Data obtained from the interviews, observation forms, and tests are presented by research question, a key way of presenting it “as it draws together all the relevant data for the exact issue of concern to the researcher, and preserves the coherence of the material” (Cohen et al., 2007, p. 468). Moreover, one of the advantages presented by this method is that “there is usually a degree of systematization [in which] the numerical data for a particular research question will be presented, followed by the qualitative data, or vice versa” (Cohen et al., 2007, p. 468) allowing the researchers to establish patterns, relationships, make comparisons, and assess qualifications from the explored data types.

For data analysis the following basic and systematic steps were followed: (1) organizing the data, (2) coding and categorizing the data collected, (3) comparison of the data, and (4) interpretation of the data. Data collected were analyzed, triangulated, and categorized. Results and conclusions are presented in the following excerpts of this article.

Results

In this section, an overview of the most recurrent in-service teaching practices that ILEUSCO teachers perform is initially presented. Next, the potential effects of these teaching practices on the development of students' communicative competence are also described.

Looking Into the In-Service Teaching Practices of ILEUSCO Faculty

In keeping with the notion that a teaching practice is not only concerned with what the English teachers actually do in the classroom, but also with the sorts of pedagogic assumptions that they go by, we found out about participants' personal motives for having chosen the teaching profession, their meaningful experiences as English learners, the theoretical principles they are committed to, and their conceptions and methodological strategies to promote the development of students' communicative competence. In addition, we present the findings of the eight observed lessons of each participating teacher.

Participants' Beliefs

Throughout the interview, the participants were asked their views on different aspects which were divided into these categories: Reasons for Becoming a Teacher, Experiences as a Language Learner, Theoretical Principles Which Guide Their Practice, Notions of Communicative Competence, and Methodological Strategies.

According to the teachers the most relevant reason for their having followed the teaching path was their own interest in the English language. In fact, seven out of nine teachers considered that taste and vocation were fundamental when selecting their career. For instance, T1 said: “My preference for English was a determining factor for my teaching vocation.” T4 stated: “My teaching vocation comes from the motivation and taste I have felt since my high school education;” and likewise T6 mentioned: “I have always felt a vocation and inclination towards teaching.” Other factors mentioned by them were family tradition and chance.

When asked about their own experience as language learners, the contributors mentioned that one of the most meaningful experiences was having had contact with good English language teachers, some of them native English speakers. Some teachers affirmed that:

T3: In high school the teacher used to speak English all the time.

T4: Having had great teachers in high school and university gave me the bases that I later used when I traveled abroad.

T9: I had English lessons for four hours a week with Colombian and foreign teachers, some of whom tried very hard to give us communicative practice. In such a way, I learnt vocabulary and structures. Having met some foreign speakers was a real life situation from which I learnt a lot.

Interestingly, most teachers seem to be guided by different theoretical principles. Among the ones they named are the communicative approach, total physical response, a communicative strategy, the eclecticism, and the inductive method. Most of them agree on the practice of activities in which students can express themselves and enjoy with others. For instance, T1 said: “Here at the ILEUSCO we manage the communicative approach. We carry out several playful activities which make our students feel at ease.”

Although they claim to obey different teaching principles, they all agreed on the idea that teacher and students must play important active roles in the classroom. The first must act as a guide who facilitates learning, for instance, making it meaningful and creating opportunities for language practice, while the others (the latter) should play an active and autonomous role so they can be consciously involved in their learning process:

T2: The teacher's role is to accompany, guide, support and cooperate in class. The learner's role should be active by experiencing, proving, trying.

T4: The teacher should act as the monitor of the learning process. Learners should be active and autonomous students aware enough of the learning process.

T6: The teacher's roles are to facilitate, guide and motivate students. The student is the main character. He is the reason of being. The learners should be attentive, willing and motivated.

T7: The teacher's roles are to guide in an effective way.The student should be 100% receptive and restless.

Teachers also agreed that ICTs should be used more as tools to support the language learning process; they think learners are eager to use them or already use them. For example, T5 and T6 respectively said: “Because of their age, students are prone to work with technology,” “ICTs are a reality which we cannot ignore.” There are those who claim to use them to foster communication and autonomous learning outside the classroom; for instance, T8 stated: “ICTs are like an external practice and help” and T9 said: “ICTs are just a tool.”

Consequently, teachers believe they tend to use methodological strategies that foster communication in the classroom through communicative activities, and use the ICTs to promote autonomous learning and communicative practices outside the classroom. Among others, the strategies mentioned are: individual or group presentations, activities based on the Internet use (duolingo app, Learning Management System Duoling, Jatket platform, online exercises, blog creation in blogspot.com, recording of voice dialogues in vocaroo.com, presentations and descriptions of pictures by Fotobable, the use of social networks such as Facebook or Linkedin, online grammar practice exercises), games, films, video, vocabulary drills, homework, songs, dialogues, sketches, pair or group work, videoclips, workshops, role play, script creation, interaction tasks, contests, and listening exercises.

Features of the Teaching Practices Used by ILEUSCO Faculty

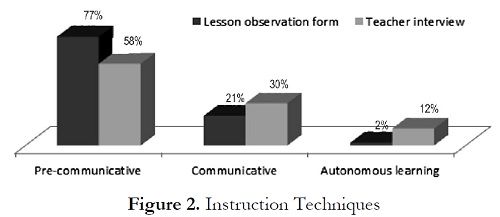

Figure 2 reveals that in a total of 72 English lessons observed, 77% of the instructional activities used by the English teachers were pre-communicative, 21% were communicative, and only 2% were based on autonomous learning. In the interview, these English teachers had admitted practing these activies with different percentages of occurrence, pre-communicative at 58%, communicative at 30%, and autonomous learning at 12%.

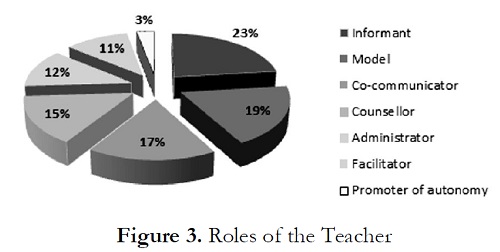

As shown in Figure 3, the English teachers played diverse roles in the 72 observed lessons. The pre-communicative roles of informant and model had 23% and 19% of occurrence, respectively. However, the communicative roles of co-communicator, counsellor, administrator, and facilitator had a thorough frequency of 55%. The role of promoter of autonomous learning had only 3%.

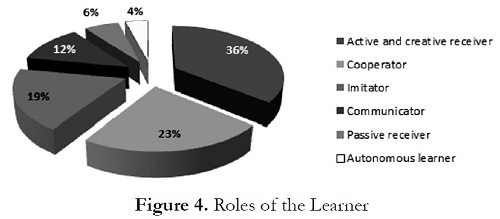

Figure 4 reflects the performance of diverse pre-communicative and communicative roles by the learners. The most frequent was the role of active and creative receptor with 36% of frequency. The second most observed role was that of being a collaborator with 23%. The role of imitator had a frequency of 19%. However, the role of communicator, that is, the one which is concerned with taking the initiative to spotaneously express one's feelings and opinions, had an occurrence of 12%. The least represented roles were the autonomous learner and the imitator with 4% and 6%, respectively.

Achievement Results of Students in the Pre-test and Post-test

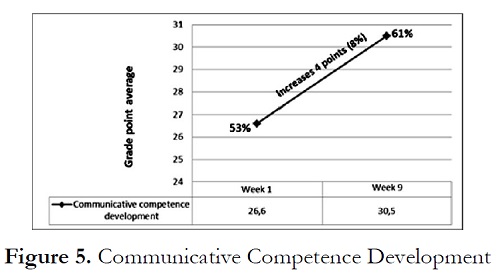

Figure 5 shows the average results students achieved on the pre-test and the post-test. On the first one they got a mean of 2.66 and on the second one a mean of 3.05, on a scale of 1 to 5. Even though there seems to be a slight amount of progress in these results, the difference does not turn out to be meaningful enough as to assert that the students have already acquired communicative competence in the target language.

General Discussion

In this section, the previously shown statistical results are turned into three comprehensive conceptual categories through which the research questions are tackled. In addition, an emerging category concerned with the way the teachers reacted to the findings is also presented.

Recognition of Teachers' Beliefs

As has been suggested by Richards, Gallo, and Renandya (2014), the nature of teacher change (and improvement) depends on understanding the beliefs and principles they operate from. More specifically, here is an overview of the way ILEUSCO teachers conceptualize their work.

Most of ILEUSCO faculty admits having entered the teaching profession driven by their teaching vocation or inspiration from their former teachers. With regard to their experiences as language learners, it is worth mentioning that some of the teachers enhanced the communicative methodology their teachers practiced at their high school or university. Some others contended that they had the opportunity to practice their English with native speakers. Others stated that their initiative to study English came from having had good grades or from having failed English tests.

As to the theoretical principles underlying their teaching practices, most of the participating ILEUSCO teachers invoked the communicative approach. One of them said he had recourse to eclecticism. Another said he used the multiple intelligences theory. Other discrete responses were the inductive method, total physical response, and ICTs.

Most of the participants identified the notion of communicative competence as knowing how to make meaningful and functional use of the target language, either in a written or oral way, without disregarding the importance of giving attention to accuracy.

In order to achieve this, ILEUSCO faculty recognized the need that the teacher play diverse roles such as facilitator, guide, motivator, model, and monitor. As far as learners are concerned, they are expected to be autonomous and active participants e.g., aware enough of their learning process. The main methodological strategies that ILEUSCO faculty claims to be using are interaction tasks, pair work, group work, presentations, games, video, the learning management system Edmodo, and other web-based activities.

Finally, all of the teachers acknowledged the relevance and usefulness of ICTs in the English learning and teaching process.

Prevalence of Pre-Communicative Teaching Practices

In general terms, this study revealed the prevalence of the pre-communicative teaching practices in comparison to the communicative or autonomous learning based ones. As a matter of fact, the ratio of pre-communicative activities to the other two types was 2 to 1. According to Littlewood (1998), pre-communicative activities are focused on accuracy and give priority to structures, functions, and vocabulary. Particularly, the ones that took place with higher frequency were answering questions, oral reading, filling in the blanks, and other drills.

However, the English teachers are increasingly making efforts to develop more communicative activities, especially functional ones through which, according to Littlewood (1998), interaction becomes less controlled by artificial conventions and meanings. Social interaction activities were the least frequent. One possible explanation for this is that the English classroom is not being exploited enough as a real and alternative social context where more authentic communication tasks can be developed.

Moreover, it was clear that both teachers and students played pre-communicative and communicative roles. Teachers showed a strong trend to give information about the language structures and to carry out repetition drills. With lower frequency, they assumed the role of facilitator which, according to Richards and Rodgers (2004), implies promoting interaction. As far as students are concerned, they seemed to be willing to carry out listening comprehension exercises and to take an active part in functional communication tasks. Bastidas Arteaga (1993) exactly suggests that the learner should play an active role and become responsible for his or her own learning process.

Effects of Teaching Practices on the Development of Communicative Competence

On the whole, the teaching practices adopted by the ILEUSCO faculty seem to have had a somewhat strengthening effect on the development of some components of the communicative competence. Students demonstrated a proportional increase of eight points from the pre-test to the post-test. Such an improvement was more evident when students served ideational, manipulative, heuristic, or imaginative functions, those being important components of pragmatic competence (Bachman, 1990). To a lesser extent, the administered tests also revealed students' progress in their organizational competence, which is concerned with the ability to control the structure of language and with the knowledge of cohesion and rhetorical conventions for joining utterances to form a text (Bachman, 1990).

One of the possible explanations for these linguistic and communicative achievements lies in the fact that pre-communicative and communicative activities are undertaken by teachers as a continuum. Cooperative learning activities and the use of ICTs served as catalysts for making the transition between pre-communicative and communicative tasks. Cooperative learning was promoted by means of pair or group work which, according to Jolliffe (2007), enabled students to improve their own learning process and their peers', based on mutual help. Some of the teachers also used diverse web tools through which their pedagogy catered to different learning styles, especially the ones of the “digital generation” who “approach learning as a ‘plug-and-play' experience; [and] are inclined to plunge in and learn through participation and experimentation” (Duderstadt, Atkins, & Van Houweling, 2002, p. 9).

Etic and Emic Reflections

Once data were gathered and analyzed, each of the participating teachers was made aware of the main findings of their prevailing teaching practices and their students' results on the administered tests. This was intended to have them reflect on the whys and wherefores for what happens in their respective classrooms.

In broad terms, some of the teachers tried to make sense of the research findings by pinpointing reasons such as class size, differences in the ages of students, lack of time to cover the syllabus completely, among others. A few teachers adopted a defensive posture by questioning the theoretical foundations of the study. Others justified the lack of more communicative tasks in their classrooms due to the coursebook syllabus. However, it seems that few teachers took the methodological guidelines provided by the teacher's book into account in order to promote more interaction in the English class.

All of the participating teachers agreed that the use of ICTs can facilitate the development of students' autonomous learning. However, these teachers also stated that technology-based instruction is time demanding and represents an additional labor load for them because there needs to be an asynchronous revision of tasks. Some other teachers seem to lack for strategies to make efficient use of ICTs.

Finally, it is just through these arguments and counter arguments made by ILEUSCO teachers that new exploration and professional development alternatives can be conceived and put into practice.

Conclusions

In order to provide a thorough view of the way the research problem was tackled, the following conclusions were derived:

The most common teaching practices used by the ILEUSCO faculty were based on structural and quasi-communicative activities which imply that the teacher and the students play pre-communicative roles. However, a great deal of students seemed to have a more communicative commitment.

There seems to be a mismatch between these observed teaching practices and the way the participating ILEUSCO teachers conceptualized their work from a communicative perspective, as reflected in their own expressed beliefs and assumptions.

Most of these teaching practices were developed by using the adopted coursebook, which provides teachers with methodological guidelines and suggested activities aimed at a functional use of the target language. But the teachers seemed to have disregarded these helping tools and opted for getting through the syllabus in a conventional way.

In general terms, it was established that the teaching practices used by the ILEUSCO faculty had a satisfactory influence on the development of students' communicative competence, more at the level of the pragmatic component than the organizational one. This was an interesting finding which challenges the expectation of matching the prevalence of pre-communicative teaching practices with the achievement of better grammatical results on the students' part.

Likewise, this study showed that some of the ILEUSCO teachers were also committed to promoting cooperative learning as well as to incorporating the use of ICTs into the English lessons, especially through the Edmodo platform. However, we were faced with the limitation of not having done any systematic follow-up of the students' autonomous learning since no proper conditions were generated in the English classroom for its promotion or implementation.

Finally, it is hoped that this first research endeavor at ILEUSCO can be considered as the point of departure for future explorations with the active participation of the ILEUSCO teachers as agents of their self-actualization and professional development.

References

Ausubel, D. P. (1963). The psychology of meaningful verbal learning. Oxford, UK: Grune & Stratton. [ Links ]

Bachman, L. F. (1990). Fundamental considerations in language testing. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Bastidas Arteaga, J. A. (1993). Opciones metodológicas para la enseñanza de idiomas [Methodological options for language teaching] (1st ed.). Pasto, CO: JABA Ediciones. [ Links ]

Canale, M., & Swain, M. (1980). Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. Applied Linguistics, 1(1), 1-47. [ Links ]

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2007). Research methods in education. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Duderstadt, J. J., Atkins, D., & Van Houweling, D. (2002). Higher education in the digital age: Technology issues and strategies for American colleges and universities. Westport, CT: American Council on Education and Praeger Publishers. [ Links ]

Flórez Ochoa, R. (1994). Hacia una pedagogía del conocimiento [Towards a pedagogy of knowledge]. Bogotá, CO: McGraw Hill. [ Links ]

Harmer, J. (2007). The practice of English language teaching. Cambridge UK: Pearson Longman. [ Links ]

Insuasty, E. A., & Zambrano, L. C. (2014). Análisis del proceso enseñanza-aprendizaje del inglés en las instituciones educativas públicas del Huila [Analysis of the English teaching-learning process in public educational institutions in Huila] (unpublished report). Neiva, CO: Universidad Surcolombiana. [ Links ]

Jolliffe, W. (2007). Cooperative learning in the classroom: Putting it into practice. London, UK: Paul Chapman Publishing. [ Links ]

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2007). Reflecting on the cognitive-social debate in second language acquisition. The Modern Language Journal, 91, 773-787. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2007.00668.x. [ Links ]

Littlewood, W. (1998). Communicative language teaching: An introduction. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Malderez, A. & Bodóczky, C. (1999). Mentor courses: A resource book for trainer-trainers. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Richards, J. C., & Rodgers, T. S. (2004). Approaches and methods in language teaching. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Richards, J. C., Gallo, P. B., & Renandya, W. A. (2014). Exploring teachers' beliefs and the processes of change. Retrieved from http://www.chan6es.com/uploads/5/0/4/8/5048463/exploring-teacher-change.pdf. [ Links ]

Schutt, R. K. (2012). Investigating the social world: The process and practice of research (7th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Tamayo Valencia, L. A. (2002). Modelos pedagógicos y prácticas pedagógicas en la educación superior [Pedagogical models and practices in higher education]. Paper presented at the Encuentro nacional de prácticas pedagógicas universitarias. Neiva, Colombia. [ Links ]

Vanegas Rubio, L. E. & Zambrano Castillo, L. C. (1997). Cómo enseñar inglés en primaria: una propuesta metodológica [How to teach English in primary school: A methodological proposal]. Neiva, CO: Corpus Litografía. [ Links ]

Zúñiga Camacho, G., Insuasty, E. A., Macías Villegas, D. F., Zambrano Castillo, L. C., & Guzmán Durán, N. (2009). Análisis de las prácticas pedagógicas de los docentes de inglés del programa interlingua de la Universidad Surcolombiana [Analysis of the teaching practices of interlingua]. Revista Entornos, 22, 11-20. [ Links ]

The Authors

María Fernanda Jaime Osorio holds a Master in Teaching English as a Foreign Language from Universidad Iberoamericana. She is the coordinator of the research group ILESEARCH and is currently working as a part-time teacher at Universidad Surcolombiana.

Edgar Alirio Insuasty holds a Master in English Didactics from Universidad de Caldas (Colombia). He is an associate professor at Universidad Surcolombiana and is currently the coordinator of ILEUSCO. He is also an active member of the research groups ILESEARCH and COMUNIQUÉMONOS.

- How did you get into the world of teaching?

- How did you learn English? Do you remember any meaningful experience that has influenced in your teaching practices?

- What theoretical principles do you use as a basis to your English classes? Mention some examples.

- What is the role of communicative competence in teaching a foreign language?

- What methodological strategies do you use to develop communcicative competence in your students?

- What is the role of information and communication technologies in teaching/learning a foreign language?