Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

How

Print version ISSN 0120-5927

How vol.23 no.2 Bogotá July/Dec. 2016

https://doi.org/10.19183/how.23.2.293

http://dx.doi.org/10.19183/how.23.2.293

Creating a Pedagogical Space that Fosters the (Re)Construction of Self Through Life Stories of Pre-Service English Language Teachers

Creación de un espacio pedagógico que fomente la (re)construcción del Yo mediante historias de vida de profesores de inglés en formación

Álvaro Hernán Quintero Poloa

aUniversidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas, Bogotá, Colombia. E-mail: aquintero@udistrital.edu.co.

Received: January 24, 2016. Accepted: April 2, 2016.

How to cite this article (APA 6th ed.):

Quintero Polo, A. H. (2016). Creating a pedagogical space that fosters the (re)construction of self through life stories of pre-service English language teachers. HOW, 23(2), 106-124. http://dx.doi.org/10.19183/how.23.2.293.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. License Deed can be consulted at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

People's true selves comprise a life story that may be considered as a narrative. With that idea in mind, the purpose of this article is to report on a pedagogical intervention that bridged life stories and a narrative perspective to examine nine, out of eighty, pre-service English language teachers' (re)construction of their true selves while engaged in a three-step introspective practice. Such (re)construction was manifested in written life stories which were interpreted and found to reveal these main themes: Meaningful Others in Shaping Their Self-as-Teacher, The Human Dimension in the Formation of Teachers of English, and Becoming Teachers of English Who Are Transformative, Instead of Transmissionists.

Key words: Construction of self, life stories, narrative, pre-service English language teachers.

El verdadero yo de las personas es una historia de vida que puede considerarse una narrativa. Con esa idea en mente, este artículo intenta compartir una intervención pedagógica que unió nueve historias de vida con una perspectiva narrativa para examinar cómo nueve, de un grupo de ochenta, futuros profesores de inglés (re)construyeron su verdadero yo mediante la introspección. Tal (re)construcción se convirtió en historias de vida escritas que fueron interpretadas y que mostraron estos temas principales: La Relevancia de Otros en la Formación de la Identidad como Profesor, la Dimensión Humana en la Formación de Profesores de Inglés y la Formación de Profesores de Inglés como Transformadores, en lugar de Transmisionistas.

Palabras clave: construcción del yo, historias de vida, narrativa, profesores de inglés en formación.

Introduction

Each day and semester in my university constitutes important steps for being what I am now, even if I do not remember many details, every experience has enriched my life, my mind and my heart. The reality I am living now is the result of the effect that education had on me and the decisions I have made during my life have been influenced in certain way by the academic experiences I had, therefore to choose my career related to education and languages was one of the most decisive ways in which education has defined my strengths and weaknesses for my future...along my life I have collected many and beautiful colors that I will use to create awesome landscapes of success. [sic] (Mabel)

This short story is part of a bigger narrative that was written by Mabel, a pre-service English language teacher. Apart from the metaphorical statement regarding success that Mabel wrote at the end of her short story, it is interesting to see that she recapitulates academic experiences by matching her statements to the events that actually occurred (past), are currently occurring (present), or are expected to happen afterwards (future). Additionally, Mabel constructs and makes sense of the nature of reality, that is, her experiences, memories (“my life”), intellect (“my mind”), and feelings (“my heart”). Sense making can also be understood as an epistemological dimension of stories (Barkhuizen, 2013). The story then becomes a form of narrative that should be read with caution, not only as a sequence of events structured into a story with a beginning, middle, and an end (Elliot, 2005), but also as an explicit evaluation and meaning making of those events, experiences, and social actors that have implications in the construction of the self. Narratives are related to the use of language as a social practice through which identities are negotiated and experiences storied (Norton & Early, 2011).

Even though the uses of narratives were not so commonly found in the contexts of language education research in past years, the narrative turn (Barkhuizen, 2013) in the field of applied linguistics in general, and in the area of second language (L2) teacher education in particular, is nowadays acknowledged not only with a focus on it as a genre (form), but also with a focus on it as a methodology and as data (a means of doing research). In this article, the conception of narrative is methodological with a qualitative approach (Clandinin & Connelly, 2000).

Drawing on the area of L2 teacher education, my main concern here is related to the need for pre-service English teachers to (re)construct and to make sense of their personal, academic, and professional selves. The reason for addressing such concern is twofold: First, future teachers should be called to make a transition from practices that make them dogmatize language education towards alternatives for transforming their realities as future professionals of language education, and second, the future teachers' subjectivities need to be made less absent in such processes of transformation. Even though transformation in teacher education is not an easy task, it is necessary to find a way that may enable future teachers to negotiate the processes of developing a sense of self (Bullough, 2008).

In order to address my concern, I intervened in the dynamics of one academic space called Seminar VI of an English language teacher education program of a public university in Bogotá. It was a pedagogical intervention that favored a view of narratives as a way of using language to construct stories (Bruner, 1990). Furthermore, based on the belief that language is not only a way of saying things, but of doing things (Austin, 1962), the intervention also created an atmosphere for an introspective practice in which the pre-service English language teachers could narrate the meaningful experiences of their academic formation while (re)constructing their personal, academic, and professional selves.

Theoretical Considerations

In this article, attention is paid to the self as the end, and written life stories as the means. This means-end relationship is mediated by language. In other words, from a discourse and narrative perspective, stories can be considered as the representation of experience and the self. (Re)storying meaningful life experiences is an event that calls for an introspective complexity and an alternative conception of language. Such conception needs to evolve from viewing language as a mere system of communication (Stern, 1987) towards considering it as a form of self-representation that is deeply connected to people's social identities (Miller, 2003). Language is more than a mode of communication or a system composed of rules, vocabulary, and meanings. It is also an active medium of social practice through which people construct, define, and struggle with meanings in dialogue with others. Furthermore, because language exists within a large structural context, this practice is positioned and shaped by the ongoing relations of power that occur between and among individuals.

In regard to the above view of language, Pennycook (2001) states that language can be understood as an emergent social act, rather than an external code that we acquire and reproduce: a material part of social and cultural life rather than an abstract entity. Pennycook also maintains that language is a vehicle that not only reveals, but also builds the dialogic relationships among social actors in which two dimensions of language are connected: The social dimension that is often associated with group communication and the individual dimension that is usually related to the individual sense of self. Group communication involves other people in various contexts, and the individual sense of self relates to memories and self-knowledge. The interrelationship of these two dimensions leads one to think of language as a form of self-representation. In other words, we construct ourselves through narratives and share those narratives with others (Canagarajah, 2004). Moreover, Norton (1997) maintains that people's identity is determined by the manner we relate to the world, the way we construct it across time and space, and the understanding we add to what lies behind that relationship.

The notion of identity in this article is equated with the notion of self, or the self-as-teacher that future teachers construct (Hopper & Sanford, 2004). The self can be considered as a life story since it is through narration that people construct their own selves, that is, while people make sense of their past life experiences and understand their possibilities for the future they are constructing their identities (Barkhuizen, 2008; Clandinin & Connelly, 2000; Peacock & Holland, 1993). This equation is also supported by Kumaravadivelu (2012) who describes the sense of self as a set of features of an individual's identity that relates to his/her capacity and willingness to exercise agency. From this, one could infer that the representation of the self demands reflection and action upon the experiences that an individual has had throughout his/her life, the ones he/she continues to live in the present, as well as those that project him/her to the future. This can take the shape of stories that tell and contribute to making sense of one's lived experiences.

The Pedagogical Intervention

The (re)construction of the personal, academic, and professional selves of the pre-service English language teachers called for the creation of an atmosphere for a three-step introspective practice to foster life stories. Such atmosphere was implemented in the academic space of a ten-semester English language teacher education program. The academic space was a last semester seminar (i.e., Seminar VI), which is part of the research field of the program. In addition to the research field, the program has four other fields of academic formation, namely the scientific and disciplinary field, the pedagogical field, the communicative field, and the ethical and political field.

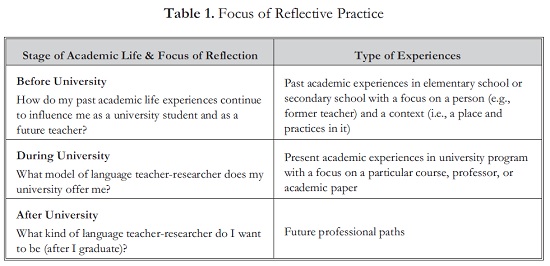

In Seminar VI, as in other seminars on the program, there has been an emphasis on teaching activities about research in a depersonalized manner. Part of that situation is the fact that the future teachers of the English language have had little or no introspective practice upon factors that impact their individual and collective dimensions. Thus, I saw it fit to modify the dynamics of that seminar. For instance, an atmosphere that fostered the pre-service English language teachers' reflective practice was created in order to (re)story meaningful experiences of their academic formation that accounted for their personal, academic, and professional selves. The future teachers focused on people, institutions, contexts, activities, and any other meaningful factors that were prompted by the questions shown in Table 1 in order to write life stories.

As a means to an end, the pre-service English language teachers reflected upon experience, confronted the unknown, made sense of it, took action, and storied experiences that changed the conditions under which new experiences were understood (Dewey, 1997). Thus the reflective practice had to do with the examination of conscious thoughts and feelings (Dickinson, 2012). It enabled further individual reflection and interpretation of experiences told from the perspective of the individuals concerned and led them to construct a more detailed picture of personal academic experience factors that had an impact on becoming a language educator.

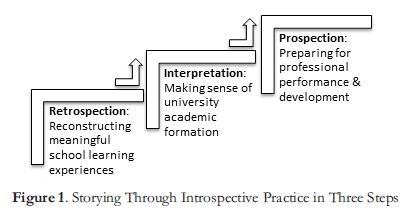

As regards the focus of the reflection in Table 1, it is relevant to describe the specific features of the reflective practice that led the future English language teachers to write their academic life stories. The stage before university included retrospection, that is, introspection time after events have already taken place; the stage during university had to do with interpretation or reflection during the time of academic formation throughout the undergraduate program; and the stage after university was about prospection, that is, introspection upon the projection for professional performance and development (see Figure 1).

Furthermore, such reflective practice took the shape of written life stories that were structured by a set of guidelines that I designed (see Appendix). This set was presented to the future teachers of English at the beginning and was used as a reference for the activities throughout the seminar. The guidelines included some instructions for reflective practice upon academic experiences before, during, and after university. Each of the three stages included activities for independent work. Near the end of the seminar, there was a wrap-up activity for pair work to conduct writing conferences, for mutual feedback, about the written stories that resulted from the previous independent work stages. At the end of the seminar, the written stories were put together into single and complete narrative texts that were submitted for analysis as explained in the following section.

The Study

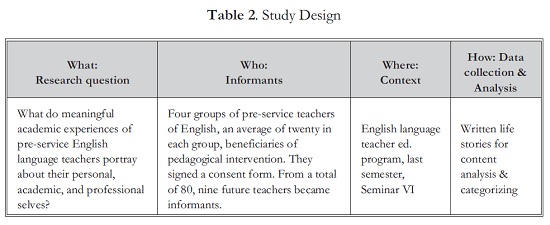

This study considered a qualitative approach that brought life stories and research together by combining two dimensions of narrative analysis: Content analysis and categorizing (Barkhuizen, 2013). In regard to the collected data, the written life stories, as a form of narrative data, here became discourses that provoked insights about how selfhood was (re)constructed (Canagarajah, 2004). The narrative data were the written stories told by the pre-service English teachers as the main social actors directly involved (Barkhuizen, Benson, & Chik, 2014) that resulted from the reflective practice of the pedagogical intervention described above. The aim of the study was to examine the way these main social actors storied meaningful academic experiences in order to (re)construct and make sense of their personal, academic, and professional selves. Eighty pre-service English language teachers benefited from the pedagogical intervention around narratives. For writing this article, a group of nine was chosen as informants from those eighty future teachers, as has been mentioned. The selection of the nine informants was done after the application of the criterion of relevance in the content of their written stories. The design of the study is summarized in Table 2.

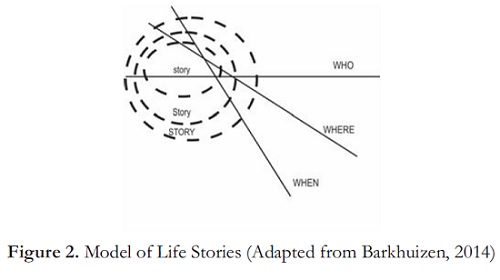

Regarding the first dimension of narrative research—content analysis, mentioned above—Barkhuizen (2014) proposes a model of life stories (see Figure 2) in which he sees the word story from three perspectives: first, story, in lowercase, involves personal thoughts, perceptions, and interactions of the life story of the author. Second, Story, with initial capital letter, refers to policies where the author has less power; this is a story in an institutional context. Third, STORY, with fixed capital letters, represents the laws of government ministries or laws of a country. In the study reported on in this article, the emphasis is on the first one, that is, the stories (lowercase) used to account for the personal domain, as they were (re)constructed by the future English language teachers. About this emphasis, it is worth mentioning that the stories showed a structure of three factors as a common feature, also mentioned by Barkhuizen (2014): Who, about stakeholders in a story; Where, referring to places where they carried out a story; and When, about the time in which the story was set.

According to Barkhuizen (2013), the second dimension, categorizing, has to do with “coding for themes, categorizing these and looking for patterns of association among them” (p. 11). In this study, themes were identified in the short stories that were part of the larger narratives written by the participants. Then, commonalities among themes were identified. Finally, commonalities were grouped as constituents of the same concept.

Findings

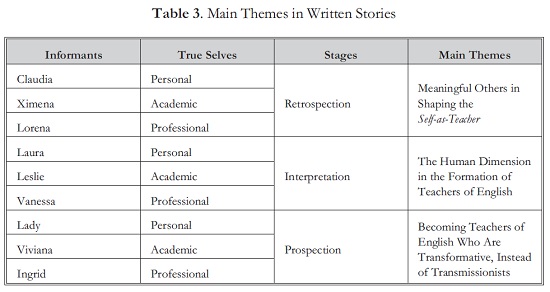

The resulting written stories by the future teachers were analyzed based on the dimensions of content analysis and categorizing proposed by Barkhuizen (2013). Table 3 summarizes the themes organized by participants (not their real names), the true selves, and the stages.

Meaningful Others in Shaping the Self-as-Teacher

The theme Meaningful Others in Shaping the Self-as-Teacher emerged as related to the fact that relatives, teachers, and classmates are social actors that play a role of identity shapers. These social actors helped the participants shape their identity through encouragement and support during learning experiences. Furthermore, these identity shapers were seen as models of authority, teaching, and personality. These three factors generate either affiliation or resistance towards a model of a teacher. The following three extracts belonging to the retrospection stage of the pedagogical intervention illustrate this idea.

I was not anymore one of the best students because this class was larger and there were very smart girls in it. I was an average student so that was really hard for me but I knew it was because of the kind of school I was in and the kind of teachers I had and also all of them used to be very strict and they wanted their students to be the best ones. I realized that this made me a responsible and constant person and taught me to do my best in everything I do. I consider that relevant to for making me a good language learner since the constancy I put in my studies not only in the learning of a second language but also in my entire academic life defines me as an achiever in my teaching career. [sic] (Claudia, Retrospection, Personal self)

In this extract, Claudia declares that there is a relationship between her strict teachers and the type of person and learner that she became. That shows the influence of a figure of authority in the construction of her teaching self.

The decision of becoming a teacher came from a long time ago, from the very beginning of my life I understood the compromise [commitment] that this career implies, my mom who is a pre-school teacher was my guide in my first years of school, she guided me towards all my academic and personal development, she taught me the essential things you need, to grow on your character, she contributed in my formation helping me to understand why learning is important, thanks to her guidance and the discipline I learned at school I can say now that I am a good learner and will be a good teacher. [sic] (Ximena, Retrospection, Academic self)

Ximena refers to her mother as the motivator of her personal and academic growth. This illustrates the presence of a relative as a shaper of Ximena's academic identity.

They taught me about values, responsibility, fun, politics, music and life itself. However, the persons that really changed me were the ones I met at (elementary and secondary) school, one of the most important places for me. My teachers that without imagining it are a good example of who I want and do not want to be as a professional. [sic] (Lorena, Retrospection, Professional self)

This extract shows how Lorena positions her former teachers as models of a professional engaged in language education that she wants to be or not to be. This implies that school teachers and their practices constitute an influence in making decisions about professional self.

Claudia, Ximena, and Lorena show themselves as individuals that undergo evolution of their true selves as other individuals or social groups become significant to them. The reference to other people that the three participants make in their texts serves the purpose of characterizing themselves as learners and future professionals. In this regard, Pavlenko and Blackledge (2004) assert that society offers alternatives for people to opt for in a specific time and place “to self-name, to self-characterize, and to claim social spaces and social prerogatives” (p. 19). That explains why individuals are continuously involved in the (re)creation of modes of being and belonging and creation of new selves. Claudia, Ximena, and Lorena encounter conditions that comply with their expectations in relation to others, as well as the opportunities to fulfill their academic formation goals.

The Human Dimension in the Formation of Teachers of English

The theme The Human Dimension in the Formation of Teachers of English results from the perception of teaching as both a human and a genuine social practice that inspires the true selves of the participants in this study. Teaching is seen as a central part of the intellectual life in school. This is a life experience of relevance for the participants because it mediates knowledge and helps to form attitudes and values. This leads the participants to perceptively and reflectively value their own university experiences as part of their formation and to consider themselves as autonomous moral agents living under a variety of real constantly-changing circumstances that can never be exactly repeated. The following short stories from the interpretation stage relate to the description of this theme:

My teaching practicum classes have aided me to be more patient with students and keep away the stress that is always implicit in our profession. Going back to all this experiences, I would say that I'm more sensitive towards students' needs because I always tend to put myself into their shoes and develop activities which involve their daily life and accomplish their particular necessities...my mother considers that I'm more human because I'm more aware of them and their learning. [sic] (Laura, Interpretation, Personal self)

Laura's short story contains an account of the empathetic component of her personal self. This implies a transition from a technical to a human dimension of teaching.

She also shared her cultural experiences with us too, which motivated us to learn more, be more interested and engaged on the class. I do not remember any other teacher doing that at the university; usually English teachers just taught the contents from a book or copies, but never got us close to the real use of the language which is a determining factor for me as a future teacher. [sic] (Leslie, Interpretation, Academic self)

In this extract, Leslie declares that there is a relationship between her strict teachers and the type of person and learner that she became. That shows the influence of a figure of authority in the construction of her teaching self.

I felt that teaching fills my life...the quality of the teachers I had at [public university] cannot be compared with teachers in private university. In the [public university] I had the opportunity of experiencing a personal and professional growing and I understand the importance of education and pedagogy. Deciding to study in a public university was the best decision I could made. [sic] (Vanessa, Interpretation, Professional self)

In this extract, Vanessa's declaration implies that her personal and professional self stems from the quality of teachers of a public university as contrasted with a private one. Quality in this extract may have to do with a balance between the technical and human dimension of teaching.

Laura's, Leslie's, and Vanessa's university stories can be thought of as experiences that led them to grow as teachers who are basically human beings full of emotionality, feelings, and rationality. For instance, Laura's portrait or portrayal of an empathetic personal identity in her story implies a rational and affective attitude towards her students' needs. The teacher-student type of relationship, as the one described by Laura, determines and can be determined by the sensitivity and sensibleness of being a language educator.

The human dimension of education in Leslie's story implies the need to rethink those teaching practices that revolve around pre-established and remote objectives that do not assure a real use of the language. An inference from Leslie's story can be that the language teaching and learning experiences should be granted with sense and genuineness in order to assure continuity and immediateness of human life in and outside schools (Apple, 2006).

In the same vein, Vanessa maintains in her story that she is aware of the role of education and pedagogy as activities that cannot be utilitarian serving only extrinsic goals; they should be valued intrinsically. The human potential of teaching is therefore an alternative to value-free and uncritical technicians (Quintero Polo, 2013).

Becoming Teachers of English Who Are Transformative, Instead of Transmissionists

The theme Becoming Teachers of English Who Are Transformative, Instead of Transmissionists relates to the conceptualization of transformation as seen in the stories about innovation and change in educational practices written by the informants of this study. Innovation can be understood as the individual and collective intentions to implement new alternatives in educational practices, and change can be considered as the perspectives from which educators see their own implementation and duration of their innovations (Piñeros Pedraza & Quintero Polo, 2006). Moreover, transformative teachers are those who move from commodity, recipes, and prescriptions towards taking risks personally or professionally and search for educational alternatives in their schools (Nieto, 2003). It is through stories that transformative educators reveal a socio-critical perspective of education elucidated in their holistic view of the teaching labor, their social commitment, and their determination to sensitize and empower learners to transform their social realities. The short stories below from the prospection stage illustrate this theme:

The university, as my second home has taught me about life, it awakens that spirit of rebellion and adventure that permits me to understand many things and realize that we can dream but reality is different...even more, as English teacher I have the possibility to change different contexts, make use of multicultural aspects and the language itself to communicate and understand the world through different experiences allowing students to appropriate of that language and become users of it in a real context. [sic] (Lady, Prospection, Personal self)

This story serves the purpose to illustrate the transformative trait in Lady's personal self. She relates her rebellious and adventurous spirit to her intention to implement changes in teaching and learning practices aimed at assuring language experiences as a means to communicate and understand the world.

Another aspect I think a teacher has to do to make a change and do things differently is the pedagogical materials and activities implementation. Over and over, students keep using the same books, doing the same grammar exercises (drills)...Why not changing the strategy to get different results? From my own classroom interactions and practices, I have realized that the way teachers teach is the same as the ones from my time... we need to move from just grammar contents, exercise books, and activities which they all have little meaning or relevance for the student. [sic] (Viviana, Prospection, Academic self)

Viviana lets one see her concern about an over emphasis on grammar descriptions that imply a view of language as something static. She also identifies with the need to transform the language teaching practices.

The practices that took place at the university, the pedagogical experience, and the research project that was developed throughout the years of my professional education allowed me to create my own vision of education and to build my profile as a foreign language teacher. For me, teaching is a process that contributes to form critic human beings, in other words, I believe that education is a commitment with society inasmuch as we contribute not only to teach a foreign language, but also we encourage our students to think about the world in which they are living and the decision they make in life. [sic] (Ingrid, Prospection, Professional self)

Ingrid refers to the formation of critical human beings as an activity that is not only about language teaching, but also about developing sensitivity towards the world and life. She declares that her commitment as a future teacher is key in achieving this type of formation.

In their stories, Lady, Viviana, and Ingrid address the possibility of transforming their future teaching labor by considering language not as a goal, but as the means for social construction and transformation. By referring to the contribution they make to construct a vision of the world, Lady and Ingrid can be interpreted as willing to become social transformers, rather than passive agents intended to reproduce officially sanctioned patterns and ideas. It can also be said that the exploration of their meaningful experiences within a formative environment allows a transition from dogmatizing language education towards transforming realities. This implies that they prepared themselves to make a transition from the heavy emphasis that their teacher education program places on the theory about how to teach, how to do research, and how to innovate in the field of language education towards a sensible and practical reality of doing language teaching, research, and innovation. The question Viviana poses, “why not changing the strategy to get different results?” leads one to think that she is willing to “step outside the mold...though needing to engage in actions contrary to her beliefs about teaching and learning in order to satisfy one or another set of externally imposed mandates” (Bullough, 2008, p. 5).

Conclusions and Implications

In this study, pre-service teachers of English wrote their own personal narratives as a way to represent their personal, academic, and professional selves. It took place by means of an alternative pedagogical intervention that fostered reflection upon the future teachers' academic life experiences. The intervention also considered writing as a practice that contributed to the (re)construction of the future teachers' selfhood. These elements led to a study of nine informants' life stories in order to answer the question what do meaningful academic experiences of pre-service English language teachers portray about their personal, academic, and professional selves?

The storied academic experiences of participants constituted a form of selfrepresentation of social interaction that involved other people. This led the future teachers of English to see themselves as part of a community where they interacted with meaningful others who shaped their identities as social actors who played the role of educators.

Additionally, the university program helped the future teachers become aware of education and language as human and social practices. It was the university that provided them the theoretical and practical tools to make sense of the human dimension of education that determines their identity as future professionals of language education and their role in society.

To finish answering the abovementioned question, it can be said that the participants have been immersed in models of the transmissionist type since elementary school. Once they entered the university, they started to find alternatives to question these models. As a result, they have developed a critical view and social sensibility in order to project themselves as transformative educators, who acknowledge the value of education and research to become agents of change.

Addressing the implications of the study, it is relevant to say that the participation of the future English language teachers in this pedagogical and research experience showed signs of the origins and reformulation of their personal, academic, and professional identity. Going back in time, making sense of the present, and having a vision of the professional path helped them see the beginnings of their opinions and beliefs, and provided a sense of reflection upon their identities in educational contexts. From this perspective, the future English language teachers are thought of as intellectuals (Giroux, 1988) who can challenge the traditional models of language education that are based on the notion of “effective instruction” (Cummins, 2008, p. 74). Their role is not merely technical or mechanical (Guerrero & Quintero, 2004) because they show themselves as willing to abandon the comfort zone of the ready-made answers and recipes in language teaching and willing to perform their roles as teachers and researchers immersed in the context of their classroom, school, or community. That serves the purpose for future teachers to explore the possibilities of (re)constructing their own selves, both as individuals and professionals who can transform their lives and be responsible for the holistic development of their true selves (Kumaravadivelu, 2003).

In addition, the pedagogical and research experience around a group of pre-service English language teachers' stories reported in this article is an effort to introduce identity work into an English language teacher education program. This type of work is connected with the challenges of the dichotomy traditional-alternative education. Moreover, past, present, and future are made a whole by the coherence of the narrative which has a beginning, middle, and end, as well as the intervention of social actors in social contexts, in a certain time. A very good definition that matches this last thought is one provided by Hinchman and Hinchman (1997) who maintain that in order for stories to offer interpretations about people's life experiences, they can be considered as “discourses with a clear sequential order that connects events in a meaningful way” (p. 3).

As a final remark, language teacher education can benefit from life stories that turn into narratives (Johnson & Golombek, 2011). Narratives should also be seen as an alternative way of carrying out research that values the future teachers' voices and active engagement in constructing the terms and conditions of their own academic formation (Pavlenko & Lantolf, 2000). This leads to the conclusion that in language teacher education programs, storying meaningful experiences (i.e., narratives) should also be considered as a model of thought.

References

Apple, M. (2006). Educación, política y transformación social [Education, politics, and social transformation]. Opciones Pedagógicas, 32, 54-80. [ Links ]

Austin, J. L. (1962). How to do things with words. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Barkhuizen, G. (2008). A narrative approach to exploring context in language teaching. ELT Journal, 62(3), 231-39. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccm043. [ Links ]

Barkhuizen, G. (Ed.) (2013). Narrative research in applied linguistics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Barkhuizen, G. (2014). Revisiting narrative frames: An instrument for investigating language teaching and learning. System, 47, 12-27. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2014.09.014. [ Links ]

Barkhuizen, G., Benson, P.,& Chik, A. (2014). Narrative inquiry in language teaching and learning research. New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Bruner, J. (1990). Acts of meaning. Cambridge, UK: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Bullough, R. V., Jr. (2008). Counter narratives: Studies of teacher education and becoming and being a teacher. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. [ Links ]

Canagarajah, S. (2004). Multilingual writers and the struggle for voice in academic discourse In A. Pavlenko & A. Blackledge (Eds.), Negotiation of identities in multilingual contexts (pp. 266-289). London, UK: Multilingual Matters. [ Links ]

Clandinin, D. J., & Connelly, F. M. (2000). Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers. [ Links ]

Cummins, J. (2008). BICS and CALP: Empirical and theoretical status of the distinction. In B. Street & N. H. Hornberger (Eds.), Encyclopedia of language and education (2nd ed., Vol. 2, pp. 71-83). New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media LLC. [ Links ]

Dewey, J. (1997). How we think. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. [ Links ]

Dickinson, S. J. (2012). A narrative inquiry about teacher identity construction: Pre-service teachers share their stories (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Missouri-Columbia, USA. [ Links ]

Elliot, J. (2005). Using narrative in social research: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. London, UK: Sage Publications. http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9780857020246. [ Links ]

Giroux, H. A. (1988). Teachers as intellectuals: Toward a critical pedagogy of learning. Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey. [ Links ]

Guerrero, C. H., & Quintero, A. (2004). Teachers as mediators in undergraduate students' literacy practices: Two pedagogical experiences. HOW, 11(1), 45-54. [ Links ]

Hinchman, L. P., & Hinchman, S. K. (Eds). (1997). Memory, identity, community: The idea of narrative in the human sciences. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. [ Links ]

Hopper, T. F., & Sanford, K. (2004). Representing multiple perspectives of self-as-teacher: School integrated teacher education and self-study. Teacher Education Quarterly, 31(2), 57-74. [ Links ]

Johnson, K. E., & Golombek, P. R. (2011). The transformative power of narrative in second language teacher education. TESOL Quarterly, 45(3), 486-509. [ Links ]

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2003). Beyond methods: Macrostrategies for language teaching. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2012). Individual identity, cultural globalization, and teaching English as an international language: The case for an epistemic break. In L. Alsagoff, S. L. McKay, G. Wu,& W. A. Renandya (Eds.), Principles and practices for teaching English as an international language (pp. 9-27). New York, NY: Routledge. [ Links ]

Miller, J. (2003). Audible difference: ESL and social identity in schools. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters. [ Links ]

Nieto, S. (2003). The personal and collective transformation of teachers. In P. A. Richard-Amato (Ed.), Making it happen: From interactive to participatory language teaching. White Plains, NY: Longman. [ Links ]

Norton, B. (1997). Language, identity, and the ownership of English. TESOL Quarterly, 31(3), 409-429. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3587831. [ Links ]

Norton, B., & Early, M. (2011). Researcher identity, narrative inquiry, and language teaching research. TESOL Quarterly, 45(3), 415-439. [ Links ]

Pavlenko, A., & Blackledge, A. (2004). Negotiation of identities in multilingual contexts. London, UK: Multilingual Matters. [ Links ]

Pavlenko, A., & Lantolf, J. P. (2000). Second language learning as participation and the (re)construction of selves. In J. P. Lantolf (Ed.), Sociocultural theory and second language learning (pp. 155-77). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Peacock, J. L., & Holland, D. C. (1993). The narrated self: Life stories in process. Ethos, 21(4), 367-383. http://dx.doi.org/10.1525/eth.1993.21.4.02a00010. [ Links ]

Pennycook, A. (2001). Critical applied linguistics: A critical introduction. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Press. [ Links ]

Piñeros Pedraza, C., & Quintero Polo, A. (2006). Conceptualizing as regards educational change and pedagogical knowledge: How novice teacher researchers' proposals illustrate this relationship. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 7, 173-186. [ Links ]

Quintero Polo, A. H. (2013). Perspectivas humanística y técnica acerca de la pedagogía: un énfasis en el currículo y la evaluación de lenguas extranjeras [Humanistic and technical perspectives on pedagogy: An emphasis on curriculum and evaluation of foreign languages]. Revista Enunciación, 17(2), 103-115. [ Links ]

Stern, H. H. (1987). Fundamental concepts of language teaching. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

The Author

Álvaro Hernán Quintero Polo is a doctoral candidate in education from Universidad Santo Tomás (Colombia). He is an associate teacher of the BA in Basic Education program with an Emphasis on English at Universidad Distrital in Bogotá, Colombia. He is a co-director of the research group Estudios Críticos de Políticas Educativas Colombianas.

Appendix: Guidelines for Reflective Practice and Written Life Stories

In this introspective or reflective practice, you are encouraged to engage in reflection upon your academic experiences before and during university studies, as well as a projection to future professional performance. The introspective practice will take the shape of written life stories (i.e., events and trajectories that provoke insights about your academic experiences) to construct a picture of you as a person, as a pre-service teacher, and as a future professional of English language education.

The introspection will be developed in three stages during the academic semester: Independent work I for retrospection upon experiences before university, Independent work II for interpretation of academic experiences during the university program, and Independent Work III for prospection upon professional performance after university.

Independent Work I (Before University)

- As a preliminary activity, you need to think of people, institutions, environments, activities, and any other influencing factor about your academic formation before university. Focus your attention on the following question: How do my life experiences continue to influence me as a university student and a future teacher?

- With the proposed question in mind:

- Choose a meaningful past event either in elementary or secondary school.

- Talk with key people or, if possible, visit the school.

- Take notes on the meaningful event, people, or place.

- Using your notes, write a narrative text that accounts for your retrospection (i.e., the reconstruction of meaningful past experiences) about your academic formation. Write as much as you wish and pay attention to contents, not to form.

- Keep the narrative text for later use.

Independent Work II (During University)

Please consider the following in order to write the continuation of the narrative text you wrote in Independent Work I.

- Reconstruct and reflect upon meaningful experiences during your university program. Think of only one key event, academic space, professor, or classmate that you may consider relevant for your formation as a future teacher. For this, focus on the following question: What kind of language teacher-researcher am I being educated to be?

- With the above question in mind:

- Choose a meaningful past event.

- Talk with key people at the university.

- Take notes on the meaningful event and people.

- Using your notes, write a narrative text that accounts for your reflection upon your own meaningful experience at the university. Write as much as you wish and pay attention to contents, not to form.

- Keep the narrative text for later use.

Independent work III (After University)

As the continuation of Independent work I & II

- Conduct an inquiry on graduate programs and schools that you consider related to your own profile as a future English language teacher. Use the following question for this work: What kind of language teacher-researcher do I want to be (after I graduate)?

- With the above question in mind:

- Inquire about graduate programs of your interest (local, national, international) that fit your personal and academic profile.

- Inquire about schools where you could apply for a job. Prefer a match between the school's philosophy and your personal and academic profile.

- Take notes on each aspect that you may consider relevant.

- Using your notes, write a narrative text about your projection as a future professional of language education. Write as much as you wish and pay attention to contents, not to form.

- Keep the narrative text for later use.

Wrap-up Activity: Pair Work

Use the narrative texts that resulted from the Independent Work I, II, and III to have a writing conference with a classmate.

- Share your texts and talk with your classmate about the following questions:

- What meaningful event/person/context did you decide to focus on for your narrative texts?

- Why does that event/person/context represent a lot of meaning for you?

- How did the meaningful event/person/context shape your own view of your academic formation and your future career as a professional of language education?

- After talking with your classmate, your answers to the questions above may lead you to make some additions to your narrative texts.

- Incorporate your classmate's feedback into your texts and make the corrections you may feel are relevant.

- Submit the resulting narrative texts to your professor.