Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

How

Print version ISSN 0120-5927

How vol.24 no.1 Bogotá Jan./June 2017

https://doi.org/10.19183/how.24.1.348

http://dx.doi.org/10.19183/how.24.1.348

More Than Half a Century Teaching EFL in Colombian secondary schools: Tracing Back Our Footprints to Understand the Present

Más de medio siglo de enseñanza del inglés en el bachillerato colombiano: tras las huellas del pasado para entender el presente*

Jesús Alirio Bastidasa

aUniversidad de Nariño, Pasto, Colombia. E-mail: jabas3@yahoo.es.

Received: October 10, 2016. Accepted: December 19, 2016.

How to cite this article (APA 6th ed.):

Bastidas, J. A. (2017). More than half a century teaching EFL in Colombia secondary schools: Tracing back our footprints to understand the present. HOW, 24(1), 10-26. http://dx.doi.org/10.19183/how.24.1.348.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. License Deed can be consulted at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

The main theme of the 50th ASOCOPI Conference held in 2015, was an opportunity to celebrate not only its accomplishments, but also to reflect on the situation of the English as a foreign language teaching and learning process in Colombia. The purpose of this article is to share with the readers the results of a study entitled “The History of Teaching English in Colombian High Schools: 1962-1994.” The report is based on a documentary analysis and on testimonies of key informants about such topics as: teaching planning, objectives, syllabi, methods, and materials, and their impact on the history of teaching English as a foreign language. Conclusions will be drawn at the end of the article.

Key words: English as a foreign language, English language teaching, history of ELT.

El tema central del Quincuagésimo Congreso de ASOCOPI, celebrado en 2015, fue una oportunidad, no solo para celebrar los logros de la Asociación, sino también para reflexionar sobre la problemática de la enseñanza y el aprendizaje del inglés en Colombia. El propósito del artículo es compartir con los lectores los principales resultados del análisis crítico de la enseñanza del inglés entre 1962 y 1994. El método utilizado se basó en el análisis de documentos oficiales, libros de texto y testimonios de profesores de inglés de la época de estudio sobre las siguientes temáticas: planeación de la enseñanza, objetivos instruccionales, programas analíticos, métodos y materiales. Además, se incluyen las principales implicaciones de cada uno de los temas para la historia de la enseñanza del inglés en la escuela secundaria y las respectivas conclusiones.

Palabras clave: enseñanza de idiomas, historia de la enseñanza del inglés, inglés como lengua extranjera.

Introduction

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”

George Santayana

The theme of the 50th ASOCOPI Conference, “Half a Century Making History in ELT: Tracing Back our Footsteps,” held in Medellín, Colombia, in October 2015 constitutes an important motive to reflect on the history of teaching English in Colombia. These reflections are critical because they can help us understand the situation of learning and teaching English as a foreign language (EFL) in the Colombian educational context.

Although historians have strong arguments to support the importance of historical studies in any discipline, in the teaching of English to speakers of other languages (TESOL) field, there has been very little of this type of research. For example, internationally there are only three well known books about the history of language teaching: one by Kelly (1969), the second by Howatt (1984), and the third—which is the second edition of the previous one—edited by Howatt and Widdowson (2004). In Colombia, it was found that there is only one book on this topic written by Gómez (1971).

Consequently, there is a need to continue conducting more research, on the one hand, to update the history of EFL teaching and, on the other hand, to get a better understanding of its problematic situation in our Colombian high schools. One of the specific objectives of our study (Hidalgo, Bastidas, Muñoz, Caicedo, in evaluation) was to analyze the teaching planning designed and implemented by the Ministry of National Education (MEN) from 1962 to 1994 in terms of the structure of the course programs, the objectives, the syllabi, the methods, and the materials. The previous period was chosen because in 1962 the MEN published the first national language course program and in 1994 the new law of education (Law 115) was issued. Under this law the teaching of English was to be introduced starting from primary school, an official decision that could have represented a major change for the benefit of students’ EFL learning.

Method

To fulfill the objectives of the study, we mainly used a qualitative approach and an historical type of research study. We analyzed and interpreted some primary sources coming from the MEN, the publishing companies, the ASOCOPI association, the HOW journal, and from some articles and doctoral studies conducted in the US. We also interviewed some key authorities in the field who have lived the experience of teaching EFL in Colombia, and also applied a questionnaire to high school teachers.

In the next section we report the results, discussion, and some conclusions of the study, based on the analysis of the MEN’s EFL course programs, the textbooks, and the testimonies.

Results and Discussion

In this section, the findings and discussion of the analysis of the teaching planning at a national level, the objectives, the syllabi, the methods, and materials proposed by the MEN course programs are presented.

Teaching Planning

Teaching planning is an essential component in education because it serves to help educators make decisions in order to get the objectives and aims of a program in an economic, secure, and efficient way. In Colombia, there is some evidence that shows that the MEN had been interested in organizing a structure to be in charge of planning the teaching of languages. To accomplish this goal, they created a specific institute called “Instituto Electrónico de Lenguas” in 1958, which was then renamed “Instituto Electrónico de Idiomas (IEI)” by Decree 3092, signed by the President of Colombia on November 21, 1959. This institute, first, was dedicated to offering language courses to the public and to English teachers and then to the design of teacher training courses. In addition, the MEN signed an agreement with UCLA in California, USA, in 1962 (Asociación Colombiana de Profesores de Inglés, ACPI, 1963), to establish an institute called “Instituto Linguístico Colombo- Americano, ILCA”, which had to fulfill three main tasks: (1) to organize specialized courses in areas related to Applied Linguistics for English teachers, (2) to offer intensive courses of English for teachers who needed them, and (3) to design six Teachers’ Guides to improve the teaching methodology of English in both public and private high schools. Furthermore, the MEN had set agreements or asked for academic cooperation from the Colombo-American Center founded in Bogotá in 1942, the British Council established in 1940, and the Fulbright Commission that started its duties in 1957. Most of these agreements had the purpose of contributing to the improvement of teaching English in Colombia, not only in the secondary schools, but also in the universities. At last, a special recognition has to be given to the Colombian Association of Teachers of English (ASOCOPI) founded in 1966. Activities, such as the national conferences, regional seminars and workshops, and the publication of the HOW journal and the Newsletter have also helped teachers to develop professionally in TESOL and its related disciplines. Finally, the B.Ed. programs of languages, some of them founded in the 1960’s, have provided the theoretical and practical foundations in TESOL and its related disciplines, so that new teachers can put them into practice in high schools.

As a result of the aforementioned structure and agreements, the MEN started to design, edit, and disseminate language programs nationally. In 1962, they disseminated the first program of “Spanish, Literature, English, and French” around the country. The next program of “Spanish, Literature, and Languages” was published in 1974. Then the “Program of English” was issued in 1982 and handed in to teachers on summer vacation courses; and finally, they published the “Supplement to the Official Program of English” in 1988. The covers of these programs are shown in Figure 1.

The evidence mentioned above is an asset for the MEN because it shows that they were conscious of the need and importance of the teaching planning of English; also, it helped so that Colombian teachers could count on a specialized institution dedicated to the teaching planning of languages, to the design, publication, and dissemination of official programs, which could serve as useful guides for educators to be able to design their own course, unit, and lesson plans, and to the offer of teacher training courses.

In spite of the existence of this evidence, some of the main problems are: some of the programs (e.g., 1962’s and 1974’s) do not refer to all of the components of a course program, which usually covers the general and specific objectives; detailed contents divided into units; complete information about approaches, methods, and procedures; audio-visual materials; evaluation criteria; and appropriate and updated references. Also most programs had been designed by members of the MEN and sometimes with the support and advice of the British Council, the Fulbright Commission, the Binational Centers, and some universities. That is, they had been produced by the top levels, and delivered from the top authority to the schools. This is what is called top-down decisions. Most of the time, these types of decisions are not well received by the “on the ground users,” because those decisions are removed from the real world of everyday teaching; they are not the result of agreements with the teachers, and they are perceived as impositions from the top. Finally, there is no clear sense of continuous improvement and consistency in the design of the teaching planning. For example, while the 1962 program covers most of the components, the 1974 program is very synthetic and lacks information about specific objectives, contents of units, and suggestions about the use of audio-visual aids and textbooks. However, in 1982 the MEN, through the IEI, provided a very complete and well supported program both theoretically and methodologically. Finally, although the 1988 program was meant to be a supplement to the 1982 program in relation to communicative methodology, the contents of the units and the supplementary materials of the 1982 program were eliminated. In addition, in the 1988 program, there was no coherence between the description of each course, which is based on reading skills, and the objectives of the units, which emphasize oral and written communication.

One of the most important components of a course program is objectives, and this is the topic of the next section.

Objectives of EFL Teaching

In planning any school course a very important component is objectives, either longrange or short-range ones, because they represent the students’ learning results expected by national, regional, or institutional authorities and teachers to be accomplished at the end of an educational stage, a school year, a unit, or a lesson. They are also important to determine the course program, the organization of contents, the selection of instructional materials, the design of tasks, procedures, and methods, and the assessment and testing of students’ academic achievement (Mattos, 1974).

To get the most out of objectives, they should be written clearly and precisely, and should include some minimum level criteria for successful achievement. In addition, objectives should be realistic and attainable. The four programs issued between 1962 and 1988 covered general and specific objectives, so that teachers knew the concrete learning outcomes of students’ learning, both at the end of each year and at the end of high school.

A careful analysis of the objectives written in the four programs in terms of congruence between general and specific objectives, appropriateness of their formulation, characteristics, and possibility of achievement shows that the MEN was not consistent. First, the general and specific objectives of the 1962 and 1974 programs are not congruent because while the general objectives focus on the development of the four language skills, most of the specific objectives refer to grammar. Fortunately, this incongruence is overcome successfully in the 1982 program. Second, the objectives stated in all of the four programs consist of the action and the contents. But only the 1982 and 1988 programs incorporated the achievement indicators. In addition, the 1962 and 1974 programs demonstrate confusion between objectives and contents in the statement of specific objectives. Third, the objectives of the 1974, 1982, and 1988 programs are clear, precise, and measurable, but most of the 1962 program objectives are vague, imprecise, and ambiguous. Finally, while the general and specific objectives of the 1962 and 1982 programs could be achieved, those of 1974 were too ambitious and those of 1988 were too many to be accomplished at the end of high school. This fact was corroborated by the designers of the 1982 program when they referred to the effect of the audio-aural methods previously applied in Colombia: “Unfortunately, the objectives were too ambitious for our environment and therefore were not achieved” (MEN, 1982, p. 3, translated by the author). It is also important to add that in the four programs, there is no reference to the aims of the Colombian educational system. This might suggest that in the decades which started with the years 1960, 1970, 1980, and 1990, the objectives of the teaching of English were not connected to the aims of the educational system.

In conclusion, the previous analysis shows that there is a pattern of irregularity, incompleteness, and discontinuity in the formulation and characteristics of the objectives proposed by the MEN between 1962 and 1994. This means that high school English teachers could not rely on most of the objectives stated in the official programs, with the exception of those stated in the 1982 program, which was the most complete and attainable one.

As a result of the statement of objectives, a teacher is also establishing the contents to be learned by the students. In the TESOL field this contents is called syllabus, an area developed since the 1970’s, as discussed in the following section.

EFL Language Syllabi

A syllabus is a set of themes, topics, or items to be taught in a certain period of school time. Crombie, for example, defines it as “a list or inventory of items or units with which learners are to be familiarized” (as cited in Bastidas, Alvarado, Ossa, Ruiz, & Vanegas, 1992, p. 11). Traditionally, in TESOL the items referred to grammar forms, situations, and communicative functions. In the eighties and nineties, course planners started to design syllabi based on abilities, tasks, and contents (Krahnke, 1987). It is important to clarify that in most of the planning activities, the previous syllabi were not used in isolation, that is, the language courses combined two or more types of syllabus, but they could keep one type as the core one.

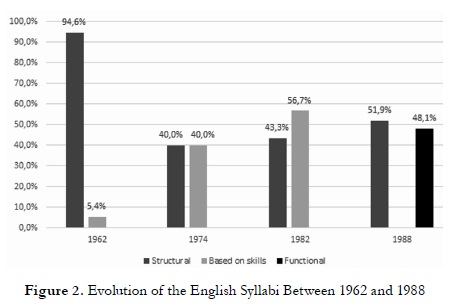

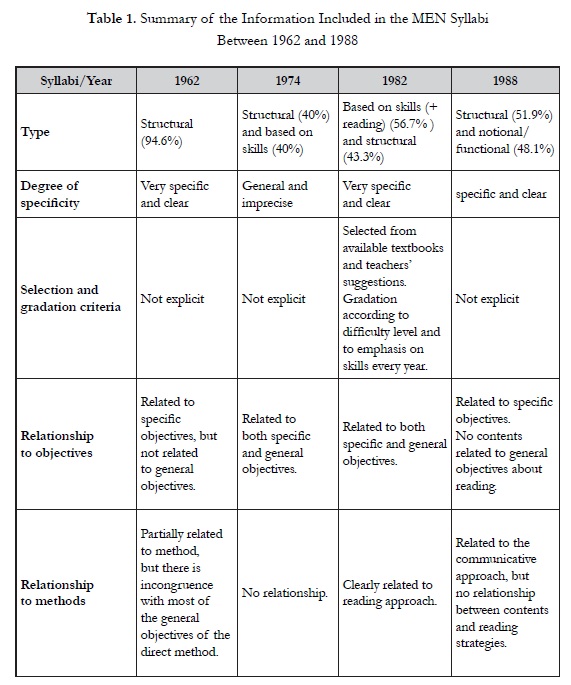

The EFL programs published by the MEN demonstrate the use of the structural syllabus (1962’s), structural and based on skills syllabus (1974’s and 1982’s), and structural and notional/functional syllabi (1988’s). This indicates that there was some progress in the use of syllabi according to the international trends stated above. This development and percentage of emphasis on the syllabus type are shown in Figure 2.

Although the previous trend is plausible, a careful analysis of the pros and cons of each type of syllabus, as expressed by Krahnke (1987), of the selection and gradation criteria, of the relationship between contents and objective and between contents and methods, reveal some gaps and incongruences, which might have impeded the effectiveness of the programs. A synthesis of this analysis is presented in Table 1.

In addition to incorporating the contents to be studied, objectives also serve to identify and select the method and materials that could serve to reach them. Below, the evolution and the analysis of the approaches, methods, and textbooks proposed by the MEN and used in high schools are presented.

Evolution of Teaching Methods and Materials

In general didactics a method has been conceptualized as a set of orderly procedures composed of activities and supported by instructional materials in order to guide students to achieve objectives successfully. In addition, its importance is automatically supported and expressed without any doubt or question. In that regard, de Mattos (1974) affirms: “The importance in the method of teaching and learning is apparent, and there is no need of additional comments” (p. 78, translated by the author).

Although a similar definition was used by Anthony in 1963 in an attempt to clarify this term and to differentiate it from approach and technique, other authors have tried to support it at the level of teaching theory (Stern, 1983), or principles and techniques (Larsen-Freeman, 1986), and of a construct (Kumaravadivelu, 2006) in the TESOL field. Finally, Richards and Rodgers (1982) subordinated the concepts of approach and technique to method and affirmed that this is composed of three levels: approach, design, and procedure. In this way, Richards and Rodgers practically converted the method into a curriculum. The previous development of the concept of method in TESOL unfortunately has caused confusion instead of clarification as Mackey had already stated in 1965.

The TESOL field has been very dynamic and rich in the design and implementation of teaching methods, most of them developed according to the context of the US and Europe, and then spread around the world through reference books or textbooks. For example, Richards and Rodgers (2014) refer to 17 methods and approaches; they are: oral approach, situational language teaching, audio-lingual method (ALM), communicative language teaching, content based instruction, content and language integrated learning (CLIL), whole language, competency-based language teaching, task-based language teaching, text-based instruction, lexical approach, multiple intelligences, cooperative language learning, natural approach, total physical response, community language learning, and suggestopedia.

As a result of the analysis of data collected from documents, textbooks, interviews, and questionnaires, we can affirm that in Colombia the MEN has promoted the use of various methods according to international trends. This is corroborated by the history of teaching EFL in secondary schools, which demonstrates the use of methods from grammar-translation method (GTM) to the communicative approach (CA). According to Gomez (1971), from the 1850’s to the 1950’s, the textbooks used in high schools were mainly based on the GTM. He provides evidence of 12 textbooks published in that period of time. Although these textbooks were based on the GTM, some of them also included oral activities and information about phonetics taken from the oral methods that were being proposed in the US and Europe by the beginning of the XX century, especially from the direct method (DM), which was spread around the world, mainly by Berlitz (1888/1992, 1907). In the 1960’s the MEN suggested the use of the DM and there is evidence of its usage in the textbook Let’s Learn English in our high schools. In the 1970’s, although the MEN recommended the integration of a variety of methods, such as the natural method, the DM, the audio-visual method, the grammatical method, the ALM, the transformational method, etc., the adoption of such textbooks as Practice Your English, English 900, English This Way, New Concept English, New Horizons in English, Target, Lado English Series, Bridges to English, and English for Today, among others, shows that the teaching of English in our high schools followed the ALM. This was also corroborated by most of the testimonies given by university teachers who were high school teachers at that time. For example, Mr. García stated:

[The methodology] was rote and repetitive, with an audio lingual tendency, but it did not have a sense of conviction for the teacher, although it was comfortable. The textbooks were small books that included annotations...they weren’t at all bad texts, however for the teacher it was very easy to skip through their pages. The exercises were easy for some students and impossible for others; they required nearly automatic production, they were more about memorizing. This was the method of learning at the time. What we tried to address was language production; but we weren’t prepared for that yet. (Miguel García, personal interview, August, 2011, translated by the author)

The dissatisfaction with the ALM and the oral methods motivated some university teachers (e.g., Silva, 1977), ASOCOPI (1977) and the MEN, ASOCOPI and the British Council (Mendoza & Díaz, 1977) to start designing and implementing materials and workshops to develop the students’ reading comprehension skills. In addition, the MEN, through the IEI, designed a new program of English in 1982 with the support of an English language teaching officer from the British Council in order to develop high school students’ comprehension of written texts, but without ignoring the other language skills. This is indicated in the 1982 program:

For a long time in Colombia it was thought that audio-lingual methods helped to fulfill the objectives of learning foreign languages, because they attempted to develop within the students all of the linguistic skills of a native speaker. Unfortunately, the objectives were too ambitious for our context and therefore they were not achieved. (MEN, 1982, p. 3, translated by the author)

In this way, the methodology of the 1980’s was guided by a reading approach, which was supported by the reading theories and strategies of that time (e.g., Grellet, 1981; Scott, 1982). In addition, the IEI organized and implemented a teacher training program offered each year from 1984 to 1988 to prepare in-service teachers from all of the Colombian regions, so that they could implement the new program and put into practice the reading strategies and materials received and practiced in the summer vacation courses (Gutiérrez, 1985). They could also select activities from the textbooks promoted by the publishing companies. Examples of specialized textbooks that emphasized reading were Conquest (Escobar, Fisher, & Zimerman, 1981), Reading & Understanding (Durán & Pearse, 1983), Taller de Inglés (Jiménez, 1986), and Reading English is Fun (Cardona, 1987). Evidence of the courses and materials designed and implemented by the IEI is supported in one of our key testimonies as follows:

We ourselves had a thermometer, which was the high number of teachers involved in our courses who shared with us their experiences of school throughout the country. When one had finished the course, they would tell us about the difficulties they faced, what they had accomplished, and what had been the most difficult areas for them. The instructional materials were made by us ourselves. (Melida Blanco, personal interview, August, 2011, translated by the author)

The design and implementation of the RA in our high schools were a very important contribution for the accomplishment of EFL objectives that were more realistic and achievable. Notwithstanding, the spread of the CA around the world in the 1980’s arrived in Colombia very soon, and the academic community started to write about it. For example, Issue 49 of the HOW: English Teaching Magazine (April-June, 1984) was devoted to this approach. In addition, various editorial companies started to promote communicative English as a second language (ESL) textbooks.

Consequently, the 1990’s mark the establishment of the communicative era. The Supplement to the 1982 Program of English issued in 1988, textbooks from the end of the 1980’s and beginning of 1990’s, and the testimonies of academic authorities corroborate this historical fact. For example, in the Supplement to the Program of English it states:

The main purpose of this publication is to offer English teachers throughout the country an up to date review of the published program from 1982. It included a methodology chapter with techniques taken from the communicative approach that had been put into practice in training courses and seminars in recent years. (MEN, 1988, p. 1, translated by the author)

Also the textbooks suggested by the IEI in the 1988 program are these: Odyssey, I love English, In Touch, Prism, On Your Way, Side by side, World English, and Turning Points, whose authors asserted that they were based on the CA. In addition, a very relevant and outstanding event in the history of teaching of English in Colombia was the publication of such textbooks as Express it in English and Interacting in English (Angel, Pappenheim, & Ruiz, 1983, 1987), and Looking Around (Silva & Roldán, 1988), all of them by Colombian authors. These textbooks were based on the CA and attempted to respond to the Colombian students’ needs. The covers of these textbooks are shown in Figure 3.

Even though the methods promoted by the MEN demonstrate a positive evolution for the history of teaching English in high schools in Colombia, a closer analysis of their application in the classroom reveals some drawbacks, which might have damaged the effectiveness of teaching and the students’ academic achievement. First of all, there is some evidence provided by some high school and university teachers, who affirm that the national programs were not used to design their institutional English programs. In most situations, they were designed according to the contents of the textbooks that were produced and published in the US or Great Britain for ESL students, with the exception of the Colombian textbooks published in the 1980’s. Consequently, both methods and textbooks produced for an ESL context were adopted for an EFL context, which we all know has more differences than similarities (Bastidas, in press; Maple, 1987). Secondly, although some teachers used textbooks designed following a specific method, some testimonies of university teachers indicate that the high school teachers adapted the contents and exercises under the GTM guidelines. For example, the grammar points were explained in Spanish, the vocabulary was practiced by memorizing lists of words in both English and Spanish, and the readings were used for translation purposes (Bastidas, interview October, 2011).

Third, most of the teachers preferred popular methods and the textbooks based on such methods, without understanding that there is no ideal method, no unique method, and no fixed method that could be used in any context (Kumaravadivelu, 2006; Mackey, 1965; Stern, 1983). Lastly, some of the classroom realities of our Colombian high schools that have prevailed over time, such as: large groups, reduced number of hours per week, lack of audiovisual aids, teachers’ low level of proficiency in English, and incomplete knowledge and skill in the use of methods, have become serious obstacles to applying those methods that emphasize the development of the oral skills, such as the DM and the CA (Bastidas, 1991; Oviedo, 1981; Strevens, 1977). This is supported by the following testimony:

There were too many students, there was a period where classes were conducted with 50 students in 6th, 7th, and 8th grades. In an extremely overpopulated class, the teacher couldn’t ensure a good standard of learning, above all without audio-visual equipment...still to this day there are many problems: the high number of students has always been constant, there are a lack of teachers, and even more a lack of prepared teachers, not only in terms of language, but also in methodology. (Euclides Valencia, personal interview, August, 2011, translated by the author)

To sum up, the MEN, with the advice and support of such institutions as the Fulbright Commission, the American Embassy, the British Council, the ASOCOPI association, and the universities, had promoted the use of up-dated methods and textbooks to teach English in Colombia according to international trends. The most notable methods and approaches have been the GTM, the DM, the ALM, the reading approach, and the CA. Despite the fact that there is clear evidence of the use of textbooks and audio-visual aids written according to the guidelines of the previous methods and approaches, the weakness of the unique method that cannot fit into any context, the inappropriateness of ESL textbooks for EFL contexts, the influence of some GTM activities in the adaptation of textbooks, and the classroom constraints of our Colombian schools have produced a generalized dissatisfaction with the reduced EFL teaching effectiveness and the low high school students’ level of academic achievement.

Conclusions

The urgent need to get a better understanding of the traditional and persistent problems of the EFL learning and teaching processes in our Colombian high schools motivated the conduction of this historical study between 1962 and 1994. Additionally, the study responded to the necessity of updating the history of the evolution of EFL teaching in our country.

The findings of the study reveal that there has been an important evolution in EFL teaching in Colombia from 1962 to 1994. This evolution and progress have been shown in the planning of teaching, in the syllabi, in the methods and in the textbooks used in high school classrooms. First of all the MEN, in consultancy with such institutions as the Fulbright Commission, the British Council, the Binational Center in Bogotá, the ASOCOPI Association, and some Colombian and American universities, have promoted the previous development through the design, publication, and dissemination of course programs at a national level in 1962, 1974, 1982, and 1988. In addition, the syllabi progressed from structural and based on skills type syllabi in the 1970’s and 1980’s to structural and notional/ functional type syllabi in the late 1980’s and early 1990’s and this progress responded to the international trends (Kranhke, 1987).

Finally, according to the primary sources consulted and the testimonies of key authorities, who were high school or university teachers in the period of the study, there was a clear change and evolution in the methods and the textbooks suggested by the MEN and implemented in the classrooms by teachers. For example, the evidence shows that in the 1960’s the method most promoted and partially used in class was the DM. This was, additionally, supported by the use of such textbooks as Let’s Learn English, which was based on the DM according to its characteristics. In the 1970’s, although the MEN suggested the use of all the available methods up to 1974, the testimonies of key authorities, of high school teachers, and the use of textbooks showed that the most frequently applied method was the ALM. Despite the fact that the change to oral methods was a novelty by the 1960’s and 1970’s, the dissatisfaction of many authorities in the field (e.g., Silva, 1977) and of the IEI’s teams of teacher trainers (MEN, 1982)with the students’ academic achievements as a result of the use of the previous methods and objectives, favored the emergence of an approach designed and implemented according to the students’ needs in our country in the 1980’s. This was the reading approach that was supported by the reading theories of the epoch (MEN, 1982). In addition to the reading materials designed by the IEI, some national and international university teachers published textbooks (Cardona, 1987; Durán & Pearse, 1983; Escobar et al., 1981; Jiménez, 1986; Silva, 1977). At last, the late 1980’s and the early 1990’s represented the flourishing of the communicative era in Colombia. This fact was corroborated by the Supplement to the 1982 Program published in 1988 by the MEN and by the use of a series of textbooks that claimed to be based on the CA. Something that needs to be highlighted for this period of the history of teaching English in Colombia is the publication of the series of textbooks by Angel et al. (1983, 1987) and Silva and Roldán (1988). These series were written in response to the needs of Colombian students and were guided by the principles of the communicative approach.

A critical analysis of the previous findings indicates that the MEN has made commendable efforts to plan the teaching of EFL from 1962 to 1994 through the publication of four official course programs. However, on the one hand, these programs have shown various shortcomings in relation to objectives, syllabi, and methods. In addition, they converted themselves into ideal programs in theory, with the exception of the 1982 program. On the other hand, in practice, most teachers elaborated their course programs based on the textbooks available in each decade, and in extreme cases, the textbook itself became the program. That is, the MEN neither controlled nor followed up on the application of their proposed course programs in the classrooms, and allowed the teachers to do their own planning freely. Additionally, the implementation of the ESL methods and textbooks in class was modified and maybe distorted by teachers according to their own beliefs and teaching preparation. The previous divorce between the MEN’s theoretical planning and a modified teachers’ real and personal course program design and implementation, based on ESL textbooks, can serve to understand and maybe to partially explain the very scant effectiveness of teaching EFL and of students’ learning in our Colombian high schools between 1962 and 1994.

Given the importance of the topic and the findings of this study, there is a need to continue carrying out similar historical studies, not only to understand, but also to explain the problems of learning and teaching English in our country. It is also suggested that a follow up of this research would be a study of the history of teaching EFL in secondary schools from 1995 to the present. Finally, time has come for the national and local official authorities of education, the high school teachers and students, the university researchers, and teacher educators, the ASOCOPI Board of Directors, and the international institutions related to the English language to stop working in isolation and spending so much effort and money in providing or implementing partial solutions. The problem of learning and teaching EFL in our high schools is a complex process that cannot be solved with top-down decisions focused on ideal language teaching planning, frequently based on imported international language frameworks, and on teacher training courses that emphasize language development and methodology improvement. Let us not forget that this process can be strongly affected by other critical factors, such as the learners and their own physical, cognitive, linguistic, and affective characteristics. After all, since the 1970’s learners have been at the center of the learning and teaching process. Also, context plays a very important role. Factors such as classroom and school constraints (e.g., class size, number of hours per week, lack of audiovisual aids, etc.), local and national sociocultural and educational factors, and national and international socioeconomic and political trends and mandates cannot be overlooked and ignored (Bastidas, 1991; Oviedo, 1981; Stern, 1983; Strevens, 1977; among others). What we urgently need is teamwork with the participation of representatives of all the people mentioned above, who can elaborate a state of the art approach to the learning and teaching situation of EFL in Colombia in order to formulate, implement, and evaluate a realistic, achievable, and flexible proposal to improve the level of EFL proficiency of the future generations of Colombian high school students.

*This article has been written to report the results of one of the specific objectives of the study conducted by Hidalgo, Bastidas, Muñoz, and Caicedo (in evaluation). It is also an elaborated version of a lecture given at the 50th ASOCOPI Conference held in Medellín, Colombia, on October 8, 2015.

References

Angel, M., Pappenheim, R., Ruiz, M. (1983). Express it in English. Bogotá, CO: Educar Editores. [ Links ]

Angel, M., Pappenheim, R., & Ruiz, M. (1987). Interacting in English. Bogotá, CO: Educar Editores. [ Links ]

Anthony, E. M. (1963). Approach, method, technique. ELT Journal, 17(2), 63-67. [ Links ]

Asociación Colombiana de Profesores de Inglés, ACPI. (1963). El Instituto Lingüístico Colombo-Americano empieza su segundo año [The Instituto Lingüístico Colombo-Americano starts its second year]. Revista English, 3(1), 32-33. [ Links ]

Asociación Colombiana de Profesores de Inglés, ASOCOPI. (1977). 23rd ASOCOPI Congress: The importance of reading. Paipa, Colombia. [ Links ]

Bastidas, J. A. (1991). ‘EFL’ in the Colombian high schools: From ivory tower to the poorest high school in Colombia. Paper presented at the 26th Annual National ASOCOPI Conference, Santafé de Bogotá, Colombia.

Bastidas, J. A. (in press). La educación inicial de los profesores de lenguas extranjeras [Foreign language teachers’ initial formation]. Pasto, CO: Editorial Universidad de Nariño.

Bastidas, J. A., Alvarado, L., Ossa, C., Ruiz, G., & Vanegas, L. (1992). A proposal of a framework for the teaching of English in the Colombian B.A. programmes. London, UK: Thames Valley University. [ Links ]

Berlitz, M. D. (1888/1992). The Berlitz method for teaching modern languages: English part. New York, US: The Berlitz School. [ Links ]

Berlitz, M. D. (1907). The Berlitz method for teaching modern languages: English part (Illustrated edition for children). New York, US: The Berlitz School. [ Links ]

Cardona, G. (1987). Reading English is Fun. Manizales, CO: Publicaciones Universidad de Caldas. [ Links ]

de Mattos, L. A. (1974). Compendio de didáctica general [Compendium of general didactics]. Buenos Aires, AR: Editorial Kapelusz. [ Links ]

Durán, R. M., & Pearse, E. A. (1983). Reading and Understanding. Mexico D.F., MX: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Escobar, J., Fisher, P., & Zimerman, E. (1981). Conquest. Bogotá, CO: Voluntad Editores. [ Links ]

Gómez, G. A. (1971). La enseñanza del inglés en Colombia: Su historia y sus métodos [Teaching English in Colombia: History and methods]. Bogotá, CO: Universidad Nacional de Colombia. [ Links ]

Grellet, F. (1981). Developing reading skills. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Gutiérrez, A. (1985). Teacher training courses given by the Instituto Electrónico de Idiomas (IEI), Ministry of Education. HOW: English Teaching Magazine, 6(51-52), 44-48. [ Links ]

Hidalgo, H., Bastidas, J. A., Muñoz, G., & Caicedo, M. (in evaluation). La enseñanza del inglés en la educación secundaria en Colombia: 1962-1994. Una historia basada en los programas, los métodos y los textos [English teaching in secondary school in Colombia (1962-1994): A history of the programs, methods, and textbooks]. Pasto, CO: Editorial Universidad de Nariño. [ Links ]

Howatt, A. P. R. (1984). A history of English language teaching. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Howatt, A. P. R., & Widdowson, H. G. (2004). A history of English language teaching (2nd ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Jiménez, H. (1986). Taller de inglés [English workshop]. Bogotá, CO: Educar Editores. [ Links ]

Kelly, L. G. (1969). 25 centuries of language teaching. Rowley, US: Newbury House. [ Links ]

Krahnke, K. (1987). Approaches to syllabus design for foreign language teaching. Englewood Cliffs, US: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2006). Understanding language teaching. Mahwah, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Larsen-Freeman, D. (1986). Techniques and principles in language teaching. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Mackey, W. F. (1965). Language teaching analysis. London, UK: Longman. [ Links ]

Maple, R. (1987). TESL versus TEFL: What’s the difference? TESOL Newsletter, 21(2), 35-36.

Mendoza, M., & Díaz, S. (1977). A review of the series of seminars/workshops offered by the Ministry of Education, ASOCOPI, and the British Council. HOW: English Teaching Magazine, 28, 5-8. [ Links ]

Ministerio de Educación Nacional, MEN. (1962). Programas analíticos de español y literatura, inglés y francés [Analytic programs for Spanish and literature, English, and French]. Bogotá, CO: Editorial Bedout. [ Links ]

Ministerio de Educación Nacional, MEN. (1974). Programas de español y literatura e idiomas [Programs of Spanish and literature and languages]. Bogotá, CO: Editorial Bedout. [ Links ]

Ministerio de Educación Nacional, MEN. (1982). Programa de inglés [Program of English]. Bogotá, CO: Editorial Printer Colombiana. [ Links ]

Ministerio de Educación Nacional. (1988). Suplemento al programa oficial de inglés [Supplement to the official program of English]. Bogotá, D. E.: MEN. [ Links ]

Oviedo, T. N. (1981). Ojeada a la problemática de la enseñanza-aprendizaje de los idiomas extranjeros [A glance at the problems of teaching/learning foreign languages]. Revista Lenguaje, 11, 19-29. [ Links ]

Richards, J. C., & Rodgers, T. (1982). Method: Approach, design, and procedure. TESOL Quarterly, 16(2).153-168. https://doi.org/10.2307/3586789. [ Links ]

Richards, J. C., & Rodgers, T. (2014). Approaches and methods in language teaching (3rd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Scott, M. (1982). Read in English. London, UK: Longman. [ Links ]

Silva, F. (1977). First Course in English Through Reading. Tunja, CO: Ediciones Universitarias. [ Links ]

Silva, F., & Roldan, M. (1988). Looking Around: A Communicative English Language Course for Secondary Schools. Bogotá, CO: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Stern, H. H. (1983). Fundamental concepts of language teaching. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Strevens, P. D. (1977). New orientations in the teaching of English. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

The Author

Jesús Alirio Bastidas A. is a Professor at Universidad de Nariño, Colombia. His educational background includes Postdoctoral Studies at Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, España (2011-2013) and a PhD in Language, Literacy, & Learning at University of Southern California, Los Angeles, USA (1995-1999). His publications can be found at www.researchgate.net/profile/Jesus_Bastidas2/contributions.