Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

How

Print version ISSN 0120-5927

How vol.25 no.1 Bogotá Jan./Jun. 2018

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.19183/how.25.1.402

https://doi.org/10.19183/how.25.1.402

Influence of Strategies-Based Feedback in Students' Oral Performance

La influencia de la retroalimentación basada en estrategias en el desempeño oral de los estudiantes

Angie Sisquiarcoa

Santiago Sánchez Rojasb

José Vicente Abadc

aUniversidad Católica Luis Amigó, Medellín, Colombia. E-mail: angie.sisquiarcoac@amigo.edu.co

bUniversidad Católica Luis Amigó, Medellín, Colombia. E-mail: santigo.sanchezro@amigo.edu.co

cUniversidad Católica Luis Amigó, Medellín, Colombia. E-mail: jose.abadol@amigo.edu.co

Received: July 14, 2017. Accepted: October 7, 2017.

How to cite this article (APA 6th ed.):

Sisquiarco, A., Sánchez Rojas, S., & Abad, J. V. (2018). Influence of strategies-based feedback in students' oral performance. HOW, 25(1), 93-113. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.25.1.402.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. License Deed can be consulted at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

This article reports on an action research study that assessed the influence of cognitive and metacognitive strategies-based feedback in the oral performance of a group of 6th grade students at a public school in Medellin, Colombia. Researchers analyzed students' oral performance through assessment and self-assessment rubrics, applied inventories to students before and after giving them the strategies-based feedback, and interviewed all students and one parent. Results showed that strategies-based feedback supported by previous strategies instruction can help students both increase the use of strategies and improve their oral performance.

Key words: Cognitive strategies, feedback, language learning strategies, metacognitive strategies, oral performance.

Este artículo da cuenta de una investigación acción que evaluó la influencia de la retroalimentación basada en estrategias cognitivas y metacognitivas en el desempeño oral de un grupo de estudiantes de sexto grado en una institución pública en Medellín, Colombia. Los investigadores analizaron el desempeño oral mediante rúbricas de evaluación y autoevaluación, aplicaron inventarios a los estudiantes antes y después de proporcionarles la retroalimentación y entrevistaron a todos los estudiantes y a la madre de uno de ellos. Los resultados indican que la retroalimentación basada en estrategias apoyada por una instrucción previa en el uso de éstas puede ayudar a los estudiantes a incrementar el uso de estrategias y a mejorar su desempeño oral.

Palabras clave: desempeño oral, estrategias cognitivas, estrategias de aprendizaje, estrategias metacognitivas, retroalimentación.

Introduction

This research was carried out at a public school in Medellin, Colombia. At the time the study was conducted, the students' socioeconomic strata ranged between 2 and 3 (low to middle household income). The school was divided into two big sections: primary and secondary. The schools' educational project (Proyecto Educativo Institucional [PEI])1 stated its willingness to strengthen English for the primary section, but English classes were scheduled for only two hours per week. In addition, qualified teachers were hired to teach only in high school, but in the primary section there were no teachers with a bachelor's degree in English teaching. The ones who taught in this section were practicum students and homeroom teachers, but none of them was certified to teach English.

The methodology favored for English learning was grammar instruction (Schulz, 2001) and consequently teachers focused on translation, reading, and writing. Oral skills were neither at the core of instruction nor at its outcome. As a result, students had a very low development of oral skills. In addition, assessment was strictly summative (Brown & Abeywickrama, 2010). Besides, students received only a grade at the end of each evaluation activity and teachers did not provide any kind of feedback; therefore, students did not have enough elements to reflect upon their learning process. Further, students perceived assessment as a certification process, instead of an opportunity for learning.

After considering the above-mentioned issues, we decided to set out on an intervention study that aimed to make students perceive assessment as an opportunity for reflecting and learning rather than as a result or a final grade. In addition, we wanted to help students improve their oral skills by implementing feedback that included recommendations to use cognitive and metacognitive strategies. Finally, with the results obtained through this research, we wanted to promote formative assessment practices among the school's teachers.

The intervention involved the creation of a "semillero",2 which in this particular case refers to a study group of sixth graders to whom we offered English lessons after school hours. Despite their basic level, the members of this group showed motivation and willingness to learn English. Two-hour sessions were held twice a week in the high school library. This room had enough resources, including 22 computers, internet connection, round tables, chairs, and a big screen on which media material could be shown.

Literature Review

Before starting to assess the influence of cognitive and metacognitive strategies-based feedback in 6th grade students' oral performance, it is necessary to go deeper into the different concepts pertaining to our research question. In this paper, we provide some definitions from different authors about learning strategies, assessment, and feedback.

Learning Strategies

According to Oxford (1990), "learning strategies are steps taken by students to enhance their own learning. Therefore, the use of strategies makes learning easier, faster, more enjoyable, more self-directed, more effective, and more transferable to new situations" (p. 8). Learners have the prerogative of including these steps in their learning process, but teachers can provide instruction and help students to become aware of the importance of using them. In any case, strategies are relevant for students because they can improve their oral proficiency (Huang & Van Naerssen, 1987; Nakatani, 2005) and self-confidence (Medina, 2014).

Cohen (1998) defines learning strategies as "processes which are consciously selected by learners and which may result in action taken to enhance the learning or use of a second or foreign language, through the storage, retention, recall, and application of information about that language" (p. 4). Six major groups of L2 learning strategies were identified by Oxford (1990). Next, we provide a brief definition of all of them.

According to Oxford (1990), memory strategies are used for the storage of information. They help learners link one L2 item or concept with another, but they do not necessarily involve deep understanding. Compensatory strategies help learners make up for missing knowledge. Affective strategies are related to the learners' emotional needs such as identifying one's mood and anxiety level, talking about feelings, or rewarding oneself for a good performance. Social strategies lead to increased interaction with other target language users that helps learners to better understand not only the language but also the culture (p. 46). Although all the previous strategies are useful, for the purpose of this research study we decided to focus solely on the cognitive and metacognitive ones, because through the analysis of the literature we found out that they are closely related to the theory of feedback that we considered for this study, as will be explained later when we define the concept.

Cognitive strategies (Abad & Alzate, 2016; Cohen, 2011; Cohen & Weaver, 2006) allow learners to manipulate and modify linguistic information to achieve learning goals. Oxford (1990) claims that there are four sets of cognitive strategies: practicing, receiving and sending messages, analyzing and reasoning, and creating structure for input and output. Practicing includes repeating, practicing with sounds, and practicing naturalistically. Receiving and sending messages involves getting the idea quickly and using adequate communicative resources. Analyzing and reasoning includes reasoning deductively, analyzing expressions, analyzing contrastively, translating, and transferring. Creating structure for input and output involves taking notes, summarizing, and highlighting (Oxford, 1990, p. 46). For their part, O'Malley and Chamot (1990) proposed additional cognitive strategies such as resourcing, which is using target language reference materials such as dictionaries, encyclopedias, or textbooks; and using imagery, which involves using visual images to understand or remember new information (p. 119).

According to O'Malley and Chamot (1990), "metacognitive strategies involve thinking about the learning process, planning for learning, monitoring of comprehension or production while it is taking place, and self-evaluation after the learning activity has been completed" (p. 8). Oxford (1990) established three sets of metacognitive strategies: "centering your learning, arranging and planning your learning, and evaluating your learning" (p. 136).

Centering your learning implies paying attention, overviewing information, and linking it with already known material. Arranging and planning your learning requires finding out about language learning, organizing, setting goals and objectives, and identifying the purpose of a language task. Part of this metacognitive strategy entails planning for a language task, which includes describing the task or situation, determining its requirements, checking one's own linguistics resources, and determining additional language elements necessary for the task. Finally, evaluating your learning involves self-monitoring and self-evaluating (Oxford, 1990, p. 138).

Although Oxford has continued to advance the learning strategies theory (2011), we decided to focus on her 1990's classification because it has been of considerable help in terms of understanding the notion of strategies and identifying practical examples that are appropriate for the population of this study.

Assessment

In language teaching, there is a distinction between two main types of assessment, summative and formative. According to Brown and Abeywickrama (2010), summative assessment is employed to verify how well students have reached the objectives at the end of a course or unit of instruction. However, it does not provide any suggestion for improving. In contrast, through formative assessment (Brown & Abeywickrama, 2010; Maturana, 2015), teachers not only assess students' final results, but also focus on the students' learning process by delivering appropriate feedback.

As part of the assessment process, it is important to encourage learners to think about their own actions and performance. Self-assessment (Brown & Abeywickrama, 2010; Maturana, 2015) is a continuous and intentional process through which students become aware of their strengths and weaknesses so that they can make adjustments for improving or practicing.

Feedback

Some authors (Hattie & Timperley, 2007; Sadler, 1989) define feedback as (a) information regarding aspects of students' performance and understanding, and (b) recommendations to help learners become aware of any discrepancies between what they know and what they want to achieve. In any case, feedback is intended to help students correct or improve themselves. Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick (2006) state that the quality of feedback can make a difference in students' achievement of the learning goals. Therefore, they suggest some principles in order to provide appropriate feedback: (a) clarify expected performance, (b) facilitate self-assessment in learning, (c) deliver high quality information, (d) promote teacher and peer discussion about learning, (e) foster motivational beliefs and self-esteem, (f) provide opportunities to reach the desired performance, and (g) provide information to help teachers shape teaching.

In a similar vein, Hattie and Timperley (2007) suggest that effective feedback answers three questions: "What are the goals? What progress is being made toward the goal? And what activities need to be undertaken to make better progress?" (p. 86). From these premises they propose a feedback model that works at four levels: task level, process level, self-regulation level, and self-level.

The first two levels are task and process. For Hattie and Timperley (2007), task-level (or corrective) feedback refers to "how well a task is being accomplished or performed, such as distinguishing correct from incorrect answers, acquiring more or different information, and building more surface knowledge" (p. 91). Process-level feedback focuses on the main process needed to understand or perform a task. It may include information to identify relationships or errors, and recommendations to use different learning strategies.

The last two levels involve the self. Self-regulation level feedback refers to the way students monitor, direct, and regulate their actions towards a learning goal. Self-level feedback directs attention away from the task to the self. Hence, it involves personal evaluations and affect about the learner, so it focuses on aspects such as the learner's effort and engagement (Hattie & Timperley, 2007).

Strategies-Based Feedback

Our notion of strategies-based feedback came as a result of combining the learning strategies theory (Oxford, 1990) with the feedback four-level model (Hattie & Timperley, 2007). This combination emerged from us believing that feedback can include recommendations to use learning strategies in order to favor students' performances. Process-level feedback can include suggestions for using cognitive strategies because it involves "a deep understanding of learning, the construction of meaning (understanding) and relates more to the relationships, cognitive processes, and transference to other more difficult or untried tasks" (Hattie & Timperley, 2007, p. 93). Likewise, self-regulation-level feedback can include recommendations for using metacognitive strategies (Oxford, 1990) since they involve planning, reflecting, and monitoring the learning process. The integration of feedback with learning strategies facilitates the former's main purpose, which is "to reduce discrepancies between current understandings/performance and a desired goal" (Hattie & Timperley, 2007, p. 86).

Research Antecedents

In this study, we want to take into consideration the results of some research projects that were carried out in the Colombian educational context. In a study that assessed elementary school students' oral performances in response to out-of-school practice, Medina (2014) found that formative assessment is useful not only to identify factors that affect students' performances and language competence development, but also to give students opportunities to improve their learning. She concluded thereby that "formative assessment as preparation for an oral test fosters students' self-confidence to participate in a specific activity" (Medina, 2014, p. 33). Regarding strategies instruction and oral performance assessment of college level students, Abad and Alzate (2016) concluded that when rubrics are used in combination with strategies instruction, students gain greater control over their learning process and prepare more effectively to enhance their test performance.

The analysis of the problem and the exploration of the literature led to the following question: How can feedback that includes recommendations to use cognitive and metacognitive strategies influence the performances of sixth grade students in oral presentations? With this study, we had as our main goal to assess the influence, if any, of cognitive and metacognitive strategies-based feedback in 6th grade students' oral performances.

Method

The following section explains in detail how this study was carried out. First, we present the research paradigm and research methodology this study subscribes to. Second, we describe the participants' selection and their demographic characteristics. Then, we describe the data collection and analysis. Finally, we go over the intervention used in this study.

Research Paradigm and Methodology

This study subscribes to the qualitative paradigm, in which "researchers are interested in constantly communicating with the subjects in order to understand their perceptions regarding a specific phenomenon or their living conditions" (Bonilla-Castro & Rodríguez Sehk, 1995, p. 52). In addition, this study was conducted under the action research methodology (Burns, 2010), as it aimed to identify a "problematic" situation that the participants considered worth looking into—in this case, oral performance—and to attempt a positive transformation of it. As a result of our effort to intervene in the problematic situation, we provided students with learning strategies instruction and then gave them feedback that included recommendations to use cognitive and metacognitive strategies in order to help them improve their preparation for and performances in oral evaluations. Although qualitative in nature, this study included quantitative instruments to complement the data collection and analysis.

Participants

Researchers chose the participants through deliberate sampling (Lankshear & Knobel, 2004) because only the 6th graders who integrated the semillero and whose parents authorized participation through an informed consent were included in the study.

They were eight female students aged 11 to 12 years who came from a middle-class socioeconomic background. The students' proficiency level was A1 according to the Common European Framework of Reference (Council of Europe, 2001). These students were not taking any English classes other than the ones they received at school, so they considered this semillero course as an opportunity for improving their language skills.

Data Collection

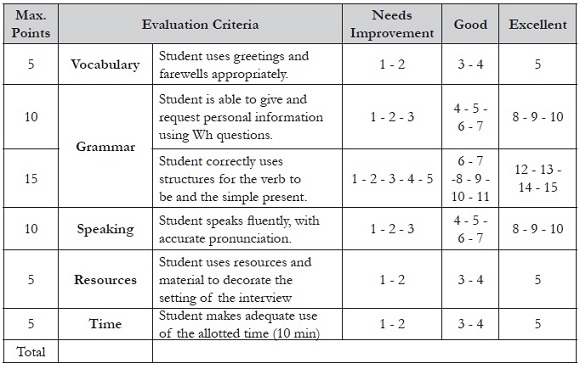

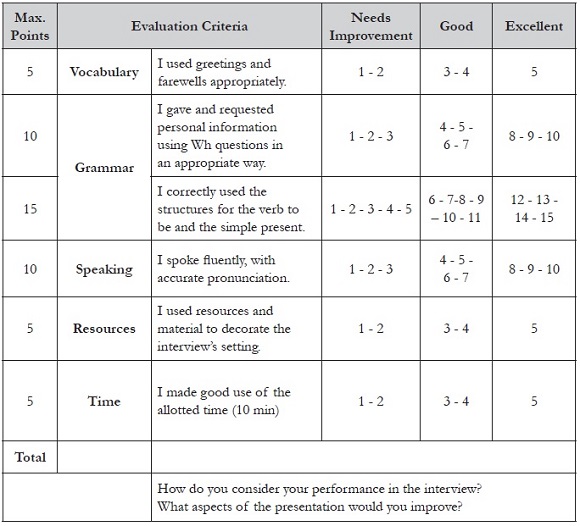

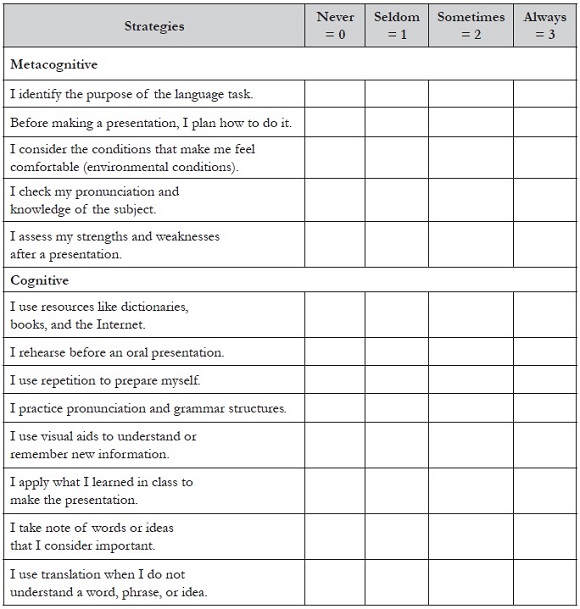

This research was developed in three stages. In the first stage, students were assigned a pre-test, which consisted of an oral presentation to assess their oral performance through a rubric (Appendix 1), followed by a self-assessment rubric (Appendix 2). After that, students completed a learning strategies inventory (Appendix 3) so we could diagnose their use of strategies before providing the intervention and the strategies-based feedback.

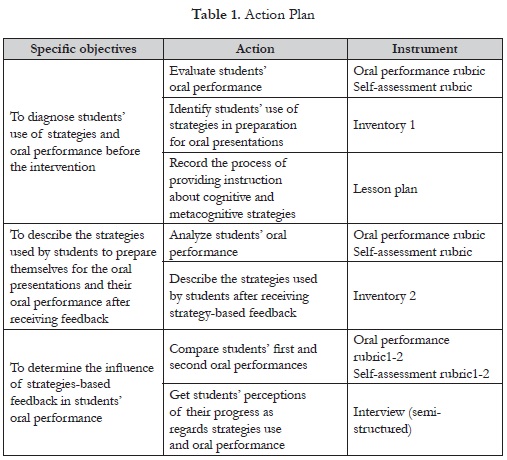

In the second stage, students received direct instruction on cognitive and metacognitive strategies (the intervention is described in detail in the section below). Later, teachers used a form (Appendix 4) through which they delivered feedback to students that included suggestions as to using specific strategies to prepare for the next oral presentation. In addition, a second oral presentation was assigned to assess whether the strategies-based feedback had had an influence on students' preparation and oralperformance. For these purposes, a second set of performance and self-assessment rubrics was applied and students answered a second inventory. Finally, to determine the influence of strategies-based feedback on students' oral performance, all the students and one parent were interviewed. Also, a comparison was made between the first and the second oral performance rubrics and between the inventories that students completed before and after the intervention. Table 1 summarizes the actions taken and the instruments used for data collection.

Intervention

Teacher-researchers designed and implemented the semillero to address the problems observed as regards students' oral production. The semillero involved four face-to-face instructional hours per week over the course of three months. As it was conceived as an extra-curricular activity, students met with the instructors on Mondays, after regular school hours, and on Saturday mornings. Taking part in the semillero involved no additional costs and was completely voluntary.

The strategies instruction workshop was developed in two of the semillero sessions. In the first one, students were trained in metacognitive strategies and in the second one, in cognitive strategies. In each session, we supplied a working definition of the strategies and generated a reflection upon their use and importance through a problem-solving activity in which the participants had to advise a person how to prepare for an oral presentation by suggesting learning strategies. Afterwards, the strategies-based feedback was delivered to each participant in a form (Appendix 4) that included strengths, weaknesses, and suggestions as to the use of specific strategies for improving their preparation and oral performance for the post test.

Data Analysis

For the analysis, three data sources were considered: the answers from the inventories, the results from the pre- and post-tests, and the answers from the interviews. In order to compare the strategies that students used for the preparation of the oral presentations, we calculated the means of the frequency of strategy use. Then, we made a distinction between the results of the inventories applied before and after the intervention.

In order to analyze the results of the presentations, we calculated the rubrics' total scores. Subsequently, in order to define the progress that students had made after the intervention, we estimated the means and then established the difference between the results achieved on both the pre- and post- tests. It is worth noting that the results obtained for the different evaluation criteria used in the rubrics were calculated as percentages to facilitate the reading of the figures by using the same scale.

Afterwards, we analyzed the answers obtained in the interviews to determine the influence of the strategies-based feedback in the oral performance. This analysis was made by categorizing, grouping, and interpreting the answers in a deductive way as the categories were established based on the learning strategies classification proposed by Oxford (1990).

We employed a number of methods to maximize trustworthiness (Burns, 2010). First, we used time triangulation (Denzin as cited in Burns, 2010) because we used the rubrics and inventories before and after the intervention. Second, we included researcher triangulation (Denzin as cited in Burns, 2010) because three people were involved in the data collection and analysis throughout the research process. Third, there was methods triangulation (Burns, 2010) as we employed different methods to collect various forms of data. For instance, rubrics and inventories provided quantitative data while the interviews generated qualitative data. Fourth, we triangulated data by including different sources of information; namely, the classroom teachers, students, and parents. By doing this, we gave voice to multiple members of the community, which also increased the level of democratic validity (Burns, 2010). Finally, the results were compared with previous studies.

Results

Students' Use of Strategies

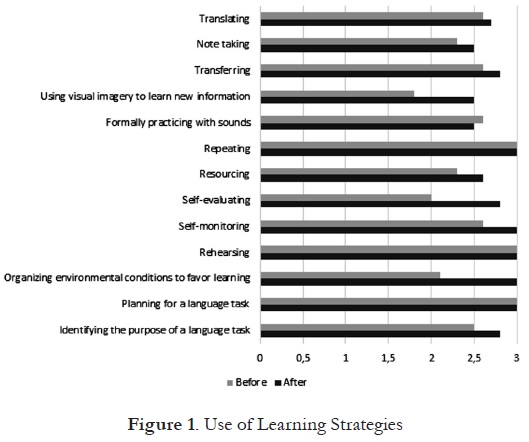

In order to diagnose the strategies used by students, we compared the answers from the first and the second inventories. These were answered by the eight participants. Figure 1 shows the average use of strategies before and after providing the instruction and the strategies-based feedback. The first seven strategies represent the cognitive strategies, and the other six, the metacognitive strategies. Each strategy is represented with two bars which show the use made by students before and after the intervention.

Before providing the instruction and the strategies-based feedback, the metacognitive strategy that students used the most was planning for a language task whereas the cognitive strategies that students used the most were repeating and rehearsing. After providing instruction and feedback, there was a change in the use of metacognitive strategies since students used not only planning for a language task, but also organizing environmental conditions to favor learning and self-monitoring. However, students were constant in the use of cognitive strategies since they continued rehearsing and repeating. Results indicate that the instruction and the strategies-based feedback provided by the researchers helped to increase the use of learning strategies employed by students.

Furthermore, we found that the learning strategies provided were used not only for preparing the oral presentations, but also for assisting tasks from other subjects. According to a parent: "Strategies have had a big influence not only for the preparation of oral presentations, but also for tasks in other subjects. They have helped [my daughter] to prepare tests, presentations." (Interview, Mother)3

Effectiveness of Learning Strategies

For the participants, the most effective metacognitive strategies were organizing environmental conditions to favor learning and rehearsing. In contrast, using visual imagery to learn new information and translating were considered the less effective strategies. One of the students stated, "for me, all the strategies are very useful, but the most effective strategy for me is practicing many times the speech before making a presentation" (Interview, student DS). Yet another student commented:

The most effective strategy for me is looking for a good place or time to study, because for me the most important is to be comfortable and relaxed and the strategy that I don't use is translating because it does not work for me. (Interview, student SP)

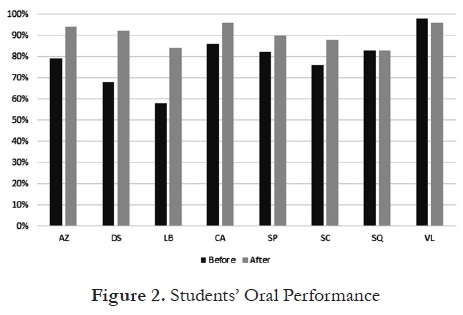

Impact of Strategies-Based Feedback on Students' Oral Performance

In the first presentation, the oral performance was good and the average grade of students was 4 (80%). In contrast, in the second presentation the average grade was 4.5 (90%). Figure 2 shows the average grades from the first and second oral presentations.

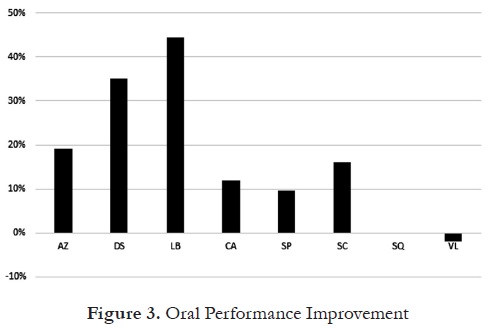

After comparing the results, we observed a positive change in students' oral performance. Thus, we concluded that the strategies instruction and feedback that students received helped to improve their performance. Figure 3 illustrates the improvement in the results after the intervention.

Considering the increase in the scores for the second presentation, we find it is possible to say that the strategies the students used helped them to improve their oral performance. For instance, when we asked a student how she considered her performance was, she answered: "I think I did it very well because I felt more fluid, more natural compared to the first presentation which was more rehearsed, more...not so fluid" (Interview, student SC).

Participants' Perception About Strategies-Based Feedback

After providing instruction on learning strategies and feedback that included cognitive and metacognitive strategies, students considered that this intervention favored their oral performance. For example, a student was asked to give her opinion about it and she answered:

I speak very softly and with the strategies you gave us, such as how to use more movements and raise the volume of the voice, I did it better. So, that was a very good thing of the strategies and the feedback. On the other hand, because I think these helped me with academic performance, with the presentations and everything. (Interview, student SP)

Data suggest that the provision of strategies and strategies-based feedback helped students feel more confident and comfortable about presenting. In this respect, another student said:

[The strategies] influenced [me] positively because, for example, they helped me to have more confidence when presenting, speaking and all that [because] I am very shy. (Interview, student AZ)

On this same aspect, the mother of one of the students mentioned:

With the recommendations you gave my daughter, she has improved the way she speaks, she pronounces better and she looks more confident. Even in the English area she has improved a lot, the teacher says she is more active in the class, so the feedback has really helped her (Interview, Mother)

In the next section, we answer the research question by explaining how strategies-based feedback can be implemented and why it is effective in helping students to improve their oral performance. We also provide some pedagogical and methodological recommendations towards its effective implementation and research.

Discussion

Results showed that strategies-based feedback supported by previous strategies instruction helped students to increase the use of strategies and thereby to improve their oral performance. This outcome was due to the fact that strategies-based feedback guided students to identify not only the progress they had made but also the strategies they could apply to overcome their communication deficiencies. Along with Dumford, Cogswell, and Miller (2016), we conclude that the use of metacognitive strategies can directly impact the effectiveness of student preparation, including how information is learned and retained. Furthermore, in our case, metacognitive and cognitive strategies optimized students' preparation and boosted their confidence to make presentations. We believe that this improvement occurred largely because strategies-based feedback and the subsequent use of learning strategies fostered both students' sense of autonomy when preparing for their presentations and their sense of competence when they actually had to present.

Strategies-based feedback favors students' autonomy and competence. It favors students' autonomy because it makes available a series of meaningful choices as regards the strategies they can use to prepare for an oral exam. The provision of meaningful choices is a key teaching strategy to foster students' autonomy, engagement, and academic achievement (Niemiec & Ryan, 2009). Hence, educators should offer students different resources and strategies to induce a meaningful decision-making process in their learning. Strategies-based feedback can also raise students' confidence level for making a public presentation that will be subject to evaluation. When students identify the strategies that help them to improve their preparation and performance, they often feel more confident about their ability to perform, which directly supports their sense of competence and self-efficacy (Niemiec & Ryan, 2009; Ryan & Deci, 2000a, 2000b).

Although strategies-based feedback can be highly beneficial for students, teachers should keep in mind some pedagogical considerations when implementing it. On the one hand, for this type of feedback to be fully effective, it should be preceded by direct instruction on what learning strategies are and how they can be used. In fact, when direct instruction in learning strategies is supplemented with strategies-based feedback, students are likely to use strategies more and to do it more effectively than they did before. On the other hand, teachers also ought to think about time, context, and theoretical knowledge. Enough time and training are required for both students' appropriation of learning strategies and teachers' implementation of strategies-based feedback. Therefore, in order to make the latter effective, teachers need to become familiar with learning strategies and feedback models, consider the characteristics of their school context, and make sufficient class time to train their students on what learning strategies are and how they can be used.

In regard to doing research on strategies-based feedback and oral skills, there are some methodological recommendations we would like to make. It would be ideal to collect records of students' actual performances. This type of data could be linked to manuscripts as meta-data that could be accessed online. In some instances, it is possible to get participants' authorization to do so. However, researchers must bear in mind that audio or video recordings of students constitute sensitive data that could endanger their integrity. In addition, the use of recording devices during presentations could intimidate some students and affect their performance. These issues are particularly problematic when participants are underage students. Ultimately, in the face of a quandary between what is convenient and what is ethical, researchers should always play on the safe side, abide by the law, and act in the best interests of their participants.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is important that teachers implement formative assessment practices that include effective feedback. According to Sadler (1998), formative assessment "is specifically intended to provide feedback on performance to improve and accelerate learning" (p. 77). Effective feedback is explicit about desired learning goals, progress that has been made, and the required steps for additional achievement (Hattie & Timperley, 2007).

Strategies-based feedback offers some significant benefits to student learning. More specifically, feedback that includes recommendations to use learning strategies can positively influence students' preparation for and performance in oral presentations because it helps them to recognize their level of progress and gives them alternatives about steps to follow in order to get better results. Further, the implementation of this type of feedback in combination with direct strategies instruction has a powerful impact on students' oral performance because it fosters their sense of autonomy and competence.

The impact of strategies-based feedback, nevertheless, goes well beyond the language classroom. By properly implementing this type of feedback, teachers can help learners to perceive assessment as an opportunity for learning and not merely as a certification process reduced to a grade. According to Jones (2005), "assessment for learning is all about informing learners of their progress to empower them to take the necessary action to improve their performance" (p. 5). Moreover, when students understand and apply the recommendations provided in the strategies-based feedback, they are more likely to appropriate those strategies and to transfer them into other areas of knowledge; therefore, strategies are applied not only for English language tasks but also for tasks in other subject areas. However, for all these benefits to be accrued, teachers need to carefully consider aspects such as time and context for implementation and adequate appropriation of theoretical knowledge regarding learning strategies and feedback models.

1PEI is the school's official long-term plan, which includes its mission, vision, principles, organizational structure, and stated curriculum.

2The term "semillero" in this article should not be taken for a research incubator, that is, a group of young researchers guided by a tutor, which is, nonetheless, a more common definition for the term within the academic context.

3Excerpts were translated from Spanish into English for publication purposes.

References

Abad, J. V., & Alzate, P. A. (2016). Strategies instruction to improve the preparation for English oral exams. Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 18(1), 129-147. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v18n1.49592. [ Links ]

Bonilla-Castro, E, & Rodríguez Sehk, P. (1995). Más allá del dilema de los métodos [Beyond the methods dilemma]. Bogotá, CO: Universidad de los Andes. [ Links ]

Brown, H. D., & Abeywickrama, P. (2010). Language assessment: Principles and classroom practices (2nd ed.). White Plains, US: Pearson. [ Links ]

Burns, A. (2010). Doing action research in English language teaching: A guide for practitioners. New York, US: Routledge. [ Links ]

Cohen, A. D. (1998). Strategies in learning and using a second language. Harlow, UK: Longman. [ Links ]

Cohen, A. D. (2011). Second language learner strategies. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning (Vol. II, pp. 681-698). New York, US: Routledge. [ Links ]

Cohen, A. D., & Weaver, S. J. (2006). Styles-and-strategies-based instruction: A teachers' guide. Minneapolis, US: University of Minnesota. [ Links ]

Council of Europe. (2001). Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Strasbourg, FR: Author. Retrieved from http://www.coe.int/t/dg4/linguistic/Source/Framework_en.pdf. [ Links ]

Dumford, A. D., Cogswell, C. A., & Miller, A. L. (2016). The who, what, and where of learning strategies. Journal of Effective Teaching,16(1), 72-88. [ Links ]

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77, 81-112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487. [ Links ]

Huang, X.-H., & Van Naerssen, M. (1987). Learning strategies for oral communication. Applied Linguistics, 8(3), 287-307. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/8.3.287. [ Links ]

Jones, C. A. (2005). Assessment for learning (Vocational learning support programme: 16-19). London, UK: Learning and Skills Development Agency. [ Links ]

Lankshear, C., & Knobel, M. (2004). A handbook for teacher research: From design to implementation. New York, US: McGraw Hill. [ Links ]

Maturana, L. M. (2015). Evaluación de aprendizajes en el contexto de otras lenguas [Learning evaluation within the context of other languages]. Medellín, CO: Fondo Editorial Funlam. [ Links ]

Medina, M. I. (2014). Out-of-class practice strategies to promote self-confidence for speaking in oral English evaluation (Undergraduate thesis). Fundación Universitaria Luis Amigó, Medellín, Colombia. [ Links ]

Nakatani, Y. (2005). The effects of awareness-raising training on oral communication strategy use. The Modern Language Journal, 89(1), 76-91. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0026-7902.2005.00266.x. [ Links ]

Nicol, D. J., & Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in Higher Education, 31(2), 199-218. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070600572090. [ Links ]

Niemiec, C. P., & Ryan, R. M. (2009). Autonomy, competence, and relatedness in the classroom: Applying self-determination theory to educational practice. Theory and Research in Education, 7(2), 133-144. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477878509104318. [ Links ]

O'Malley, J. M., & Chamot, A. U. (1990). Learning strategies in second language acquisition. New York, US: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139524490. [ Links ]

Oxford, R. L. (1990). Language learning strategies: What every teacher should know. Boston, US: Heinle & Heinle. [ Links ]

Oxford, R. L. (2011). Teaching and researching: Language learning strategies. New York, US: Routledge. [ Links ]

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000a). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 54-67. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1020. [ Links ]

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000b). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68-78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68. [ Links ]

Sadler, D. R. (1989). Formative assessment and the design of instructional systems. Instructional Science, 18(2), 119-144. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00117714. [ Links ]

Sadler, D. R. (1998). Formative assessment: Revisiting the territory. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 5(1), 77-84. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969595980050104. [ Links ]

Schulz, R. A. (2001). Cultural differences in student and teacher perceptions concerning the role of grammar instruction and corrective feedback: USA-Colombia. The Modern Language Journal, 85(2), 244-258. https://doi.org/10.1111/0026-7902.00107. [ Links ]

The Authors

Angie Sisquiarco holds a B.A. in English teaching from Universidad Católica Luis Amigó, Colombia. She works in a private school with high school students. Her interests include language assessment and research in education.

Santiago Sánchez Rojas holds a B.A. in English teaching from Universidad Católica Luis Amigó, Colombia. He has worked as an English teacher for the language center of a national public university. His interests include language assessment and language teaching.

José Vicente Abad holds an M.A. in education from Saint Mary's University, Canada. He works as associate professor at Universidad Católica Luis Amigó, Colombia. A member of the EILEX research group, he coordinates a research incubator on language teachers' education. His research interests include language assessment, learning strategies, and language teacher professional development.

Appendix 1: Oral Performance Rubric

Teacher:

Student:

Date:

Activity: Students will plan an interview of their favorite celebrity.

To complete this task successfully you need to:

- Ask for personal information using WH questions.

- Provide information using simple present structures.

- Express tastes and preferences using vocabulary and structures about likes and dislikes.

- Present the interview clearly using appropriate tone of voice, body language, good pronunciation, and supporting material.

Instructions: The activity will be done in pairs. One member will assume the role of presenter and the other the role of celebrity; then roles will be exchanged. Both will produce a questionnaire with open questions about personal information, tastes, and preferences. They will also prepare material to decorate the space where the interview will take place. Finally, it is recommended to practice the interview as often as necessary, taking into account the established criteria.

Minimum passing score: 3.0

Appendix 2: Self-Assessment Rubric

Student:

Date:

Instructions. Select one of the following performance descriptors for each evaluation criterion.

Appendix 3: Learning Strategies Inventory

How do I prepare for an oral presentation?

Student:

Date:

Instructions: Indicate to what extent you use the following learning strategies to prepare for your oral presentation.

Student:

Date: