Introduction

For several years, the Colombian Ministry of Education has been implementing a mixed course as a strategy to do two grades in one year. This educational model intends to help students who pass the average ages for fourth and fifth grades (Ministerio de Educación Nacional (MEN), 2014) to complete their primary school education. One of the issues that most of those children face when they are in a mixed course is that they skip many topics or aspects related to their educational training. Regarding the acquisition of a foreign language, several children learning under this model find it difficult to develop their oral skills. Despite the difficulties they may face, the National Ministry of Education (MEN) demands that students get an A2 level of English (based on the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching and Evaluation) when they complete the last year of their primary education (Estándares Básicos de Competencias en Lenguas Extranjeras: Inglés).

After applying a diagnostic test to students who participated in this research study, it was found that most of them did not reach the expected A2 English level, not even an A1. A first approach to the context also allowed researchers to detect problems with the coexistence of students. Aggression and behavior issues were identified in the student-teacher and student-student relationships. As an alternative to solve these problems, the research group suggested the implementation of a radio program in English. A radio program would allow students to learn the language, practice their oral ability, and develop their capacity for tolerance and respect towards others’ opinions. In fact, this alternative was considered after a deep analysis of the participants’ context, the institution’s resources, and successful civic and citizenship skills development experiences reported by countries such as Ghana, England, Canada, Sri Lanka, Solomon Islands, among others (McCowan & Gomez, 2012; UNESCO, 2014). Since the outcomes of education where the radio program is used had been proven to be effective, this research study aimed at the enhancement of students’ oral skills and at providing opportunities to develop their citizenship skills while participating in the process.

Theoretical Framework

In this section, a general concept of radio and its value as an educational strategy will be presented first. Then, since our main objective was to identify the impact of a radio program on the development of the students’ English language speaking skills and citizenship skills, a definition of the communicative competence and the oral ability in this language, as well as the citizenship competence, will be discussed.

The radio and its value as an educational strategy. The radio has remained a viable medium that proves educational worth in terms of pedagogical importance. According to Das (n.d.) on the website of All India Association for Educational Research, “[through the radio] information is transmitted to a larger population group saving time, energy, money and effective workforce.” Thereby, radio is seen as a way of broadcasting education with information and entertainment for people who cannot easily get to formal education institutions. In a like manner, Bedjou (2006, p. 28) remarks that “radio can bring authentic content to the classroom, especially in the EFL environment” which is useful in rural areas where the only source that helps students to communicate is a radio.

Throughout time, the radio has been used in different formats for educational purposes around the world; it was created with the aim to connect people and create communication. Educational radios were developed during the late nineteenth century and came into popularity as an educational medium during the early twentieth century. Although it has not had the same importance as other technologies such as television and the Internet, radio remains a viable medium that has proven its educational worth in terms of pedagogical importance. Couch (2013) states that a radio is capable of delivering high-quality educational programming to highly diversified audiences located across broad geographical expansion.

Kaplún (2002) says that a school radio procures broadcasts of value, integral development of a person and a community. Moreover, a radio program is a place of integration and inclusion for students of different ages. Additionally, school radio programs are intended to raise the level of awareness and stimulate reflection in each person. It is also a strategy that helps in the students’ English learning process. Therefore, it is a communicative space where students can expose their ideas and thoughts in a real context.

As a matter of fact, Pardo-Segura (2014) conducted a study at Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia, where she showed that radio broadcasting is an alternative that supports the enhancement of writing and reading skills in the foreign language. Moreover, she states that this strategy improves cooperative work and participants’ responsibility. In effect, school radio programs are an innovative space of socialization and knowledge construction in which the appropriation of language skills such as speaking and listening are achieved. Students can create a link between a radio program and their knowledge because radio programs are excellent stimuli to learn English while having fun.

There are different formats to present a radio program. The most common ones, according to Mefalopulos and Kamlongera (2004, p. 52) are a lecture or straight talk, interviews/discussions, drama, music, jingle/slogans, feature, magazine, and infotainment. They also mention that some basic elements should be taken into account for radio production as: technical, content, and presenters. Regarding the technical elements, they are the sound quality, special sound effects, and accent factors that can make a radio program an interesting and involving experience for the listener. The content elements are factors such as opening/closing, slogans-themes-logos, jingles, humor, simplicity, accuracy, repetitions and summaries, pacing, and interactive capability that provide the radio program with a sense of organization and program to the listener. These factors can cause the audience to have a good impression of the topics that are being presented. The last type of element is the presenters and their style of delivery. Presenters should be role models and sources of credibility as well as have clarity of speech (Ibid, p. 54).

The oral ability development. Speaking is one of the four language skills and the means by which people can communicate with others to express their intentions, opinions, and viewpoints (Burns & Joyce, 1997). According to these authors, it is an interactive process of constructing meaning that involves producing and receiving, and processing information. Its form and meaning depend on the context in which it occurs, including characteristics of the participants themselves, their collective experiences, the physical environment, and the purposes of the message. Additionally, it is often spontaneous, open-ended, and evolving.

Likewise, Aamer (n.d.) from Alama Iqbal Open University compares language as a tool for communication. Furthermore, she says that individuals cannot communicate without speech; otherwise, the language would be a simple script. As can be seen, speaking is important to express ideas and to know others’ opinions as well; it means that it is necessary to develop the oral ability permanently because any gap in communication creates misunderstandings and problems.

Nevertheless, for English language learners, oral ability is one of the most difficult language skills to develop. In fact, Segura-Alonso (2013) has found that in EFL contexts, a difficulty emerges when students can be structurally competent but cannot develop authentic communication. Moreover, the author claims that interaction is the most difficult aspect at the moment of speaking in a second language.

Spoken English cannot usually be planned or organized, unless is preparing a speech or a presentation, there is not much time for reflection so, it is frequently full of repetitions, pauses, incomplete sentences, hesitations or fillers. It needs the response of another speaker or listener, it usually comes into the form of turns and when speakers are talking, they must also pay attention to gestures, intonation, stress or even pauses that other speakers are doing because are clues to understanding the meaning of what they are trying to say. (Ibid, p. 23)

The context wherein students learn and practice English is the classroom. In EFL contexts, there is not much practical use of English in the real world because citizens may constantly communicate with each other in their mother tongue: Spanish in the case of this current study. For students, then, it is easier to go straight to the practice of Spanish to communicate with their peers and teachers. All the same, since there is not enough time in the curriculum for teachers to develop the speaking skills in the classroom —especially with a group that has discipline and behavior issues— they focus their efforts on teaching grammar and vocabulary.

One effective approach toward developing the oral ability is the task-based approach (Peña & Onatra, 2009; García Cardona, 2016; Córdoba Zúñiga, 2016). Abd El Fattah Torky (2006) states that there are three stages for task-based instruction: The pre-task stage, the during-the-task stage, and the post-task stage (See Figure 1):

Figure 1 Abd El Fattah Torky’s task based instruction model. Taken from Abd El Fattah Torky (2006, p. 101)

Pre-task activities can include inductive learning activities; consciousness raising activities; and pre-task planning. During the task stage implies speaking spontaneously focusing on fluency and using whatever language is available. Post task activities include reflection, consciousness-raising activities, as well as public performance and post-task analysis-oriented activities. These activities enable learners to allocate their attention differently between form and meaning while they are completing an earlier task. (Ibid, p. 104)

Then, taking into account that speaking is one of the hardest language skills to be strengthened due to its intrinsic characteristic of communication, this research study aimed to develop the oral skills by teaching students how to plan a radio program recording and emission through interviews, talks, section presentations, and discussions while acting as reporters.

The citizenship skills development. So far we have covered two key constructs which were the basis for the development of our research project: the radio and speaking ability. Nevertheless, one of the concepts that might have been left aside is the development of citizenship competences and skills. The use of the radio as a pedagogical strategy and the use of workshops to teach children how to record a radio emission or program allowed us to go beyond foreign language teaching per se.

The citizenship competences are described as the “cognitive, emotional, and communicative knowledge and skills that are articulated, [and that] make a citizen act in a constructive manner in a democratic society” (Ministerio de Educación, 2004, p. 8). This means that by creating opportunities for students to reconcile their differences, and peacefully and creatively solve their problems, teachers are giving them the chance to develop knowledge and skills for them to participate in the creation of a fair and democratic society.

The Colombian Ministry of Education has classified the citizenship competences into three groups: Coexistence and Peace (appraising the existence of other human beings), Participation and Democratic responsibility (making decisions based on respect towards others’ rights), and Plurality, Identity and Appraisement of differences (acknowledging and enjoying human diversity).

The use of a radio program as a strategy to enhance students’ citizenship competences works if teachers understand it as the building of horizontal communication mechanisms in which they can favor a dynamic and clear organization, which allows a democratic scholar environment. This is highly recommended by the Colombian Ministry of Education (2011, p. 32), along with communication with respect for the dignity of all the members as a base, as well as the guarantee of the promotion of a pacific coexistence, participation, and the valuing of differences. We consider these types of proposals as a balm in the times of post-conflict and education for peace; indeed, these two are the promoted pillars in Colombia nowadays. As a matter of fact, when addressing the conflict situation of Northern Uganda, which emerged in 1986, Cunningham (as cited in McCowan & Gomez, 2012) stated that:

While NGOs responded to the urgencies of the conflict and post-conflict situation, and have been successful in sensitizing people to the idea of rights, this approach is not sustainable in the long term. Indeed there is evidence that the pressure on time and resources has resulted in a superficial approach that is in danger of creating a backlash... It is necessary for comprehensive human rights knowledge to be firmly built into the taught curriculum. (Ibid, p. 11)

This indicates that if the Colombian government is to provide guidelines to empower students’ development of citizenship skills, these should be embedded to the national curriculum. Thus, English language teachers around the country would be called upon to offer students opportunities for deep reflection and practice of these skills; otherwise, it would result in students talking about doing what they think is right, but acting differently when facing troublesome situations.

There are documented case studies in which the introduction of civic education and citizenship skills in the curriculum, or the formal education of the Commonwealth countries’ students proved to be effective because education was seen as the ideal process for social cohesion to start taking place (McCowan & Gomez, 2012). In countries like Mexico, for example, the development of civic competences to construct civic praxis on children has been relevant in recent years (Escorza-Heredia et al., 2014). They state that “The social media, groups of friends, and other socialization groups provide permanent areas, in which the contents of civic education, ethics, and politics are confronted in a continuous, dialectic, and permanent process” (p. 2). Therefore, we believe that formal education settings and the institutions where our students coexist are the core places for them to learn values that help them understand and live in harmony with others who have different lifestyles, thoughts, ideas, etc.

Methodology

Action research is well known for providing teachers with the identification of areas of concern so as to deal with them by developing or testing alternatives or experimenting with new approaches (Kumar, 2011). This action research study was initiated to solve an identified immediate problem (students’ poor oral communication in the English language) through a reflective process which involved workshops, recording, reflecting and assessing a radio program created by children in the English language. Three cycles of action research were carried out and they involved the basic steps by Kemmis and McTaggart (1988): Plan, act, observe, reflect.

Instruments for data collection. Action research studies allow researchers to collect qualitative information by means of numerous instruments. For the purpose of knowing students’ interests, opinions, likes and dislikes, and their learning preferences, a survey was applied at the beginning of the study. Then, in order to learn students’ perception of the pedagogical interventions to create the radio program, three semi-structured interviews were implemented at the end of each action research cycle for a focus group of students. We also interviewed the cooperating teacher to collect her views about the students’ performances and progress in the English language at the end of the intervention process.

Another instrument to collect qualitative data from the participants was comprised of observations. Field notes taken from observing students’ behavior during each one of the interventions helped us to understand students’ social construction and negotiation of meaning. According to Kumar (2011), by analyzing the information obtained through observations, researchers can find emerging categories that help them understand the phenomenon. In addition, it provides the opportunity to study participants’ behaviors.

All the same, to collect quantitative data on students’ oral ability development, three tests were applied. Tests are described by Brown (2004) “as a method of measuring a person's ability, knowledge, or performance in a given domain.” The first test (pre-test) took place before the interventions and it had a double purpose: to learn students’ speaking level and to acquaint them with the test mechanics. A mid-term test was applied after the first intervention and a final test after the last intervention. The number and nature of questions were similar for the three tests so that the number of correct answers could be quantified and compared so as to measure students’ oral ability progress.

Participants’ background and context. The study was conducted in a lay, private-public, open-door and non-profit institution. It is concerned about children’s rights and it is linked to the National System of Family Wellbeing (Sistema Nacional de Bienestar Familiar). This institution welcomes children between the ages of 7 and 15 from marginal sectors of the city of Neiva (Colombia). These children may be at high social risk due to displacement, mistreatment, abuse, neglect, or orphanhood. The participants of the radio program in English consisted of 32 students whose average age oscillated from 10 to 14, from social stratum 1 and 2. Some of the children live with their parents, others live with their grandparents, aunts, a surrogate mother, and 3 students are interns in the institution. During the study, we worked with the whole group (32 students), but at the end only 18 remained part of the research. One of the reasons why this happened was that the remaining 14 students missed some classes when the interventions and methods took place.

The study collected the information for data analysis from a focus group of 18 students since not all the participants attended the classes regularly. Some students’ absences prevented them from taking one of the tests, or providing answers for our interviews; therefore, despite their being part of the groups in some of the sessions and their participation in the radio recording and emission, their data were discarded.

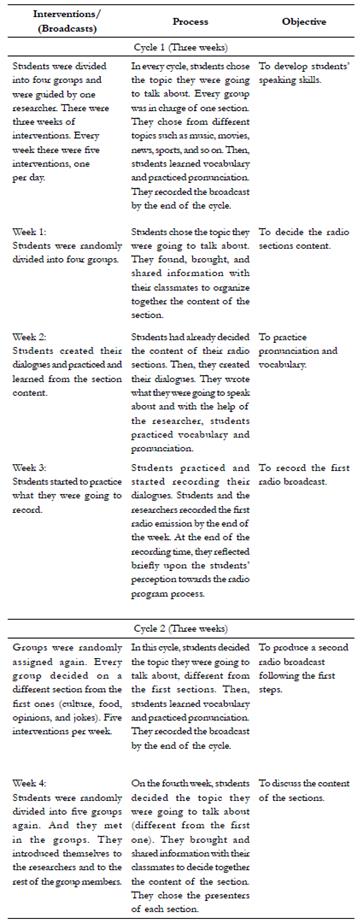

Procedure. Participants were selected by simple random sampling where students from a mixed class (4th and 5th grades) were assigned to four different groups. Each group, guided by one researcher, was composed of eight students. After three weeks and having finished the first radio emission, groups were randomly selected again for the next two cycles of action-research.

A survey, a diagnostic test, and four lesson observations were carried out to establish a diagnosis of the problem and the possible course of action (planning). During the second stage of the project, the researchers began the intervention process. This process started with the researchers teaching each of the groups the basic elements of a radio program and providing an example of the expected outcome. Each group was in charge of one section of the radio program. Once the sections were joined, the initial recording and emission of the program took place. After finishing this process, researchers and students broadcasted the program during the recess period at the institution, and then evaluated the process.

As part of the action research process, we as the researchers reflected on the process and implemented the same research instruments for a second time. Results were then analyzed and modifications to the intervention process planned. The second cycle of action research took place after the second radio program broadcast.

Pedagogical proposal. This pedagogical proposal aimed to raise methodological ideas that support the use of a radio program in the English language to enhance students’ oral and citizenship skills. Before starting the radio program, we explained to the participating students the history of radio, how a radio program is created, and what types of broadcasts exist. Each one of the four groups decided not only on the content of the section (music, movies, news), but they were also enabled to disseminate information and ideas while focusing their oral production on different issues such as conflict, cultural identity, education, music, movies, etc. Students also decided on the content and dialogues to be presented on the radio program. We as the researchers acted as facilitators and teachers in the process.

Data Analysis and Findings

To analyze the data, the six steps proposed by Creswell (2012, pp. 236-238) were followed: Prepare and organize the data for analysis; read through the data and code them; build general interpretations of them; represent findings through narratives and visuals; make a personal interpretation of the results; and validate the accuracy of the findings. Also, the data were triangulated with the instruments that we implemented to give validity and reliability to our study. We have organized the findings according to our research objectives in the following three sections:

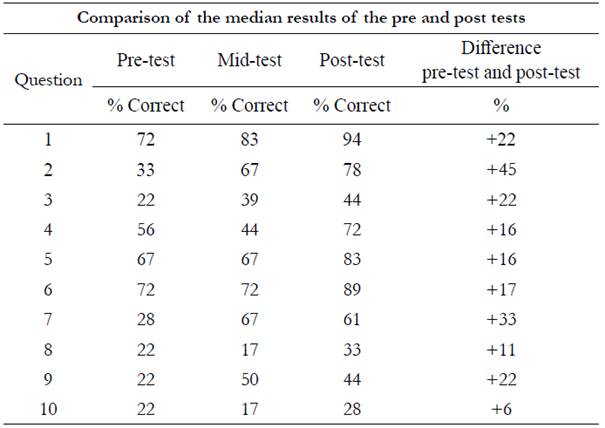

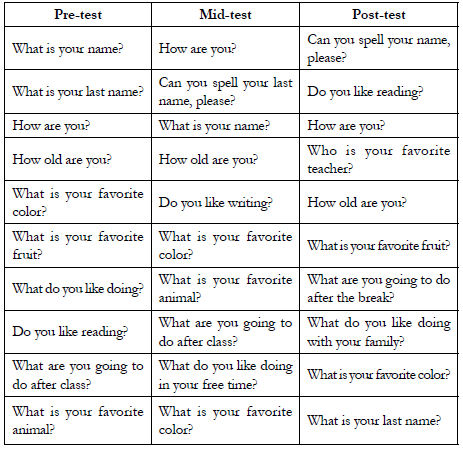

The impact of the radio program on students’ speaking skills. Three oral tests were applied in order to identify students’ improvement of the speaking skills. Each test consisted of a series of ten questions (See Appendix A) that were provided to students at three different moments: before, in the middle, and after the intervention process. Eighteen students participated. Table 2 shows a comparison between the median results of students’ correct and incorrect answers on the oral pre-test and post-test.

Table 2 shows that before the intervention process, students performed poorly in the pre-test due to aspects such as vocabulary, grammar and poor knowledge of the English language, in general. Despite their understanding some of the questions, they were not able to answer them in English. As a result, it was necessary to work on those difficulties through the interventions that took place on the different cycles. At the end of the first cycle, the second test took place and the test results showed a slight improvement in students’ oral ability. By the end of the second cycle, the final test showed a notorious improvement in comparison with the previous tests. The levels of correct answers varied from 4 to 6, which showed that the number of children who answered correctly increased. This means that children learned some basic things in the English language such as to introduce themselves, to describe events, and to identify colors, among others.

Another instrument we used to measure the impact of the radio program strategy on students’ oral skills was the interview. Three interviews in Spanish were applied before, in the middle, and at the end of the intervention process. The first interview inquired about students’ intention to participate in a radio program as part of their learning process for the English language lessons. The second and the third interviews, on the other hand, required students to assess their own oral skills progress while they took part in the radio program recording and broadcasting.

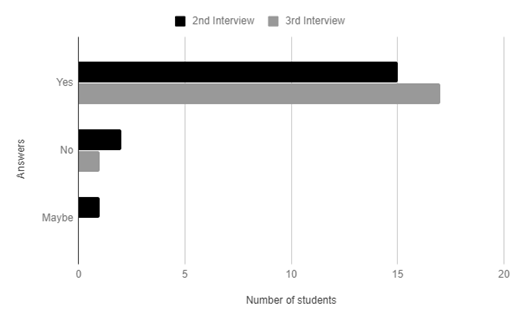

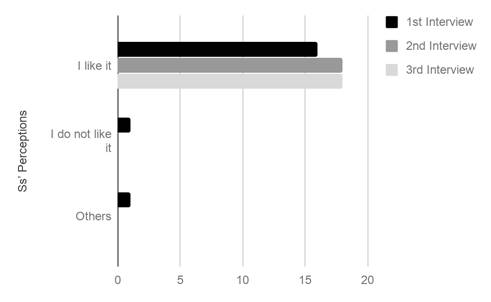

Figure 2 illustrates students’ answers to the question: Do you believe that your participation in the radio program has helped you to improve your oral skills? We can notice that in the middle of the process, there were three students whose perception was negative. They believed their oral skills did not improve after their participation in the radio program recording. Nevertheless, at the end of the process, just one out of the eighteen students from the focus group believed that his/her oral skills did not improve. Through subsequent questions, most students made it clear that they had practiced the language a lot, and that they had learned new vocabulary. A significant minority thought that even though they lacked “love” for the English language, they had learned and practiced some new structures and vocabulary through the radio program.

One of the drawbacks found through the interviews was that the learners who disliked the radio program creation process felt concerned about their classmates’ behavior because they thought that it turned hostile and aggressive when they were making decisions or discussing the topics and dialogues to be presented and recorded. Those findings led us to pay more attention to provide students with democratic and controlled environments in which they would experience freedom of speech; in other words, an environment in which they could develop their citizenship competence.

The impact of the radio program in the development of students’ citizenship skills. Our field notes were used in order to find out the development of students’ citizenship skills. Classes were observed before and during the intervention process. The participants of the project reflected on the effect of having neither qualified education at home nor enough economical resources; these students belong to a vulnerable population protected by the ICBF (Colombian Institute of Family Wellbeing). It was easy to find students whose aggressiveness caused disruptions in the English language classroom. In fact, we may have sometimes found the environment a bit intimidating and demanding at first, but this environment evolved with the passage of days and by the time the first cycle had ended, measures had been taken to achieve a transformation of students’ behavior through the development of their citizenship competence.

At the beginning, most of the students were reluctant to cooperate; they kept being rude, and provoked some other classmates into annoyance; but after some days, the students started to be interested in the different themes worked in every group and they changed their behavior to motivate themselves and their classmates to keep on; as a consequence, students’ will to learn the language was increasing.

Moreover, we noticed that students liked to work in a cooperative way, as each section of the radio program was made in groups. Actually, when the children listened to the first radio broadcast, they were glad to listen to what they were able to do. They wanted to go back to the recording process because it was funny and interesting for them. We believe that a key to provide students with a safe environment to give their opinions without the fear of being mocked or attacked by their classmates was what we called a reflective roundtable.

This exercise started with students listening to the radio program and assessing their performance in a critical and friendly manner. Students were encouraged to speak in English while participating in the reflective roundtable; nevertheless, most of them made use of their mother tongue when struggling to communicate the intended message to their peers and teachers. Students gave their opinion respectfully and everyone agreed to listen without causing interruptions. Taking turns when talking allowed them to practice their democratic right to talk, being aware of the fact that others can have different opinions, and that it is also their right to express them.

After the second radio broadcast, the students listened to it and the reflective roundtable took place again. This time, we as the researchers, facilitators, and teachers, had to intervene less. Students were more aware of the process and the respect they should exercise during their participation. Something that caught our attention was that during the assessment of the process, they recognized that they could provide a solution to the situations on which they did not agree; for instance, when making decisions about the content of the section or the creation of the dialogues, students asked one of the researchers to intervene, or they found the way to negotiate their demands so as to reach agreements and solve the problematic situation instead of making use of violence, as was previously practiced by them during our observation and planning period. We believe that students developed knowledge, attitudes, and skills during their participation in the project with these practices. We observed changes towards a more respectful attitude towards other classmates and the teachers; their conflict management and resolution, as well as their tolerance, responsibility, and respect for diversity was then developed to some extent.

Perceptions about the radio program and the project itself. Throughout the project, three interviews were done in order to find out the students’ perception of the radio program in the English language. The first was done at the beginning of the project in order to find out if students were interested in the creation of the radio program. Then, the second was carried out after the first cycle to account for students’ opinions. Consequently, the third interview took place at the end of the project, which helped to find out if the radio program was received as a positive strategy. Their answers were categorized as follows: students’ opinions about the radio program, and their desire to continue working on the recording and broadcasting of subsequent radio programs.

We found that, in general, students’ impression of the radio program was positive. Those responses support what is shown in Figure 2, where the bar graph shows that the creation of the radio programs in the English language was welcomed by the participants in the first stage of the project. It can be seen that 16 out of 18 students liked the idea of recording a radio program from the beginning of the project. Fortunately, at the end of the project, all students had a positive viewpoint of the new learning strategy. Additionally, we noticed that students believed that the radio program helped them to learn English in a non-traditional style. The next excerpts1 were taken from the students’ interviews, in which the positive effects of their participation are highlighted:

Extract 1: “I like it because I can learn English, and then I would go to other countries to teach English.”

Extract 2: “I think it is good because you teach us English, at least for some hours.”

Extract 3: “It’s good because we have learned things in English.”

Extract 4: “It was a good experience, you taught us good lessons and we didn’t waste our time.”

Extract 5: “I like English now, because of the radio program.”

Extract 6: “The best part of all this process was the joy, I think it was fun.”

The second category emerged in the second and third interviews after the first cycle had finished. Students were asked if they would like to continue working with the radio program, and all the participants wanted to keep on with the project. Throughout the project it was found that students became aware of the importance of the English language, claiming that even if they did not receive help, they would enjoy working on the project on their own since they believed they had the elements to do so, and because they wanted to learn and practice their English. Here are some of the answers given by two participants of the project:

Extract 1: “Yes, because I want to learn English, it does not matter if you are not working here, I will keep practicing my English speaking skills.”

Extract 2: “Yes because I want to be someone important, and when I travel, speaking English will be helpful.”

Extract 3: “I think the best part of the radio program was to share [time] with others. I would continue because when one speaks English, one learns many things that one did not know.”

Extract 4: “The best part of the process was making the radio [program], I would not change anything and I would continue making radio.”

We also interviewed the cooperating teacher at the institution to learn of her perception about the impact of the project on her students. She believed it was a useful project, especially because those students were about to start their secondary education. She believed the project conducted researchers to an almost personalized work with students which somehow increased their wish to know new things and pay attention.

She said: “This is a very difficult group, they are thirty-two students from different background and social strata, different families, families in which there is no union, or where there is no family; it is the reason why the only space they have to enjoy their childhood and adolescence is the Albergue.” She highlighted the importance of the project mechanics, especially the reflective roundtable strategy since it allowed students to be heard and valued. In her own words:

I would like the research group to come back again with the radio program. I would like it to be… to be like a projection to the future; that everything was managed in English because, in that way students stop being afraid, they stop being shy, they listen to themselves more easily, they feel heard, they feel more prepared for a future.

Conclusion

The creation of a radio program in the English language is a meaningful alternative for teaching a foreign language. Throughout the process, the improvement of students’ speaking skills level was evident. For instance, learners showed a remarkable advance on the speaking tests, in spite of the absence of English language teachers before the project started. However, as stated above, this absence did not affect the impact of the radio program in students’ English language speaking skills.

Additionally, on account of the teacher’s and students’ perception about the radio program, we conclude that both parties were in favor of the creation and continuity of the radio program in the English language. Both parties expressed that applying techniques like the creation of a radio program was a highly motivating and meaningful learning method. Then, we can say that the oral proficiency was not the only positive aspect enhanced through the process.

An additional point to consider is the fact that, at the beginning, some students were reluctant to participate, but at the end, those participants were the most pro-active members of the group. Of course, despite the obvious lack of good oral ability of the participants of the program they almost always showed their desire of continuing the process. This is a valuable result we want to highlight.

Finally, students could develop their citizenship skills to some extent through their participation in the project. At the beginning of the process some students’ behavior was aggressive and they were reluctant to follow rules and agreements. They showed not much respect to partners or teachers, but they progressively improved this behavior as long as the reflective roundtable spaces were provided. This was a strategy which proved to be effective so they could develop problem solving skills and appreciation towards difference.

Recommendations

Taking into account the process of creating and implementing the radio program, we observed the need for some recommendations. First of all, projects that include the use of media such as the radio are welcome to foster communication among students in both English and Spanish. This fact provides English language learners with opportunities to share views, experiences, opinions, and expectations that provoke language and general learning, and a democratic use of people’s rights. Students’ oral skills, in English and even in Spanish and their citizenship competence can be highly benefited by these types of alternatives. Second, we believe that for the project to be more successful, more time is needed for its implementation, so as to prepare a group of infants to record the radio broadcasts. It is necessary to provide pro-active students with extra activities which, at the same time, should be managed with extra care to keep their engagement and agency. Finally, further study on these matters are recommended for the purpose of exploring different alternatives of peace practices in the post-conflict times that Colombian society requires nowadays.