Introduction

The knowledge of vocabulary is one of the most challenging issues for both teachers and researchers (Coady & Huckin, 1997; Khoii & Sharififar, 2013). It is true that learning a sufficient repertoire of vocabulary is as important as learning grammar (Krashen, 1988). No one can communicate without knowledge of vocabulary; the expression of different meanings is possible only through memorizing a range of words by L2 learners (McCarthy, 1990). But, words are sometimes more than single lexical items. That is, two-to-three-word combinations are as frequent as single words in a language. These combinations of words are called collocations in the literature (e.g., Melcuk, 1998; Shehata, 2008).

Collocation is a subcategory of vocabulary. As Melcuk (1998, p.14) maintained, “Word combinations involve two lexical items, one of which is selected arbitrarily by the other lexical item to convey a particular meaning.” “The combination is not a fixed expression but there is a greater-than-chance likelihood that the words will co-occur” (Jackson, 1988, p. 96). Learners in an EFL/ESL setting have different kinds of problems including the accurate use of collocations in their daily communication, which has not been addressed appropriately by the teachers or researchers in the field, that is, researchers or teachers can only measure learners’ productive skills (writing and speaking), though they often have different problems in both skills.

Some lexical errors that happen in co-occurrence of words like “heavy tea”, “long person” arise from learners’ insufficient knowledge about how words are used together. Learners’ collocational knowledge is crucial for producing language which is both more natural and also closer to native speakers’ language (Ellis, 1996; Nation, 2001; Produromou, 2003). Lewis (1997) declared that “learners can have more effective communication only through collocations, and they have the ability of saying whatever they want with restricted language resources” (p. 33).

Previous research findings suggest that second language learners have difficulties dealing with collocations (Ellis, 1996; Lewis, 1997; Miyakoshi, 2009; Pei, 2008; Produromou, 2003; Shehata, 2008; Vural, 2010). For instance, Vural (2010) claimed that learners have problems with how to find out the meaning of words without the knowledge of collocations. Whenever one non-native speaker wants to produce language, it clearly sounds unnatural. Lack of enough exposure to the natural patterns causes difficulties for learners to produce sufficient collocations as fluently as possible.

The use of literature and literary texts, however, goes back to the grammar translation era, during which literature was considered as the main source of material to be used in the classroom, founded on the assumption that studying the literary texts of the target language was the best way to learn both the new language and the culture. But, later there was a slow movement toward discarding literature as a source to be used in the classroom, and finally, during the period from the 1940s to the 1960s, it disappeared from the language curriculum entirely, possibly because “literary texts were thought to embody archaic language which had no place in the world of audio-lingualism, where linguists believed in the primacy of speech, thus considering the written form somewhat static”, as De Riverol (1991, p.65) states. One of the most influential figures in the field of literature, Maley (as cited in Khatib & Rahimi, 2012, p.32) mentions that the lack of empirical research in support of the facilitative role of literature can be the main reason for this negative view.

Nevertheless, in the 1970s and 1980s, the growth of communicative language teaching methods led to a reconsideration of the place of literature in the language classroom. This, as Carter (2007, p.6) noted, was mainly due to the “recognition of the primary authenticity of literary texts and the fact that more imaginative and representational uses of language could be embedded alongside more referentially utilitarian output”. Furthermore, many scholars have endorsed the benefits of using literature in the language classroom (Collie & Slater, 1990; Ghosn, 2002; Hirvela, 2001; Ur, 1996; Maley, 1989; Tasneen, 2010).

Reading literature is promising in several ways. It provides authentic and varied language material; it creates contextualized communicative situations, real patterns of social interaction, and use of language (Collie & Slater, 1994)).Despite theoretical recognition of the possibly important role of literature and literary content in teaching a second language, the field of second language teaching still suffers a paucity of research in this domain. Therefore, the present study aims at bridging this gap by including literary content as a design feature in teaching collocations to EFL learners, who are often deprived of being exposed to authentic linguistic input. To this end, this study has aimed at comparing the effects of literary versus non-literary contents on EFL learners’ collocation learning. The impetus for such an empirical attempt has been that the recent theoretical arguments in favor of the potential of literary contents cannot be relied upon unless its utility is put to experimental scrutiny and verification.

Review of the Related Literature

Wilkins (1972, pp.111-112) argued that “Without grammar little can be conveyed, without vocabulary nothing can be conveyed”. Carter and McCarthy (1988, cited in Higuchi, 1999, p. 46) believe that “Three key groups in the area of language learning and teaching neglect vocabulary study: linguists, applied linguists, and language teachers”. As McCarthy (1990, cited in Higuchi, 1999, p. 12) noted, “Vocabulary should be taught through collocations…. The relationship of collocation is fundamental in the study of vocabulary, and collocation is an important organizing principle in the vocabulary of any language”.

Maley (1989, as cited in Bagherkazemi & Alemi, 2010, p.4) emphasizes ‘the use of literature as a resource for language learning”, and Higuchi (1999) argued that authors of stories rarely use unusual collocations in their works, so typical collocations should be taught through stories. As a result, he believes that EFL learners can take advantage of short stories as proper resources to get familiar with apt collocations. He also states that reading activities can really be fruitful in terms of raising learners’ consciousness about collocations.

Studies on collocation have addressed it from different angles. Waller (1993) explored the characteristics of near-native proficiency in using collocations in writing. Källkvist (1998) analyzed the types of collocational errors made by advanced Swedish learners of English. Channell (1981) investigated advanced EFL students’ use of collocations and the errors they made in using them compared with Standard English. Arnaud and Savignon (1997) compared the knowledge of rare words and complex lexical units in advanced ESL learners of French L1, and found that the learners performed better on the use of rare words than complex phrases. Bahns and Eldaw (1993) compared the collocational knowledge and general vocabulary knowledge and found that the knowledge of collocations lags behind the knowledge of general vocabulary.

EFL students find reading texts in English as complicated when they come across a new word in a text. However, it is extremely important that EFL teachers employ new strategies to help these students make those words part of their lexicon. EFL teachers use various strategies to catch students’ attention so they can become aware of unknown words and store them in their long-term memory. As mentioned above, the role of literature and literary content in foreign language teaching is under-researched so far and awaits proper investigation. Ebrahimi-Bazzaz, AbdSamad, Arif Bin Ismail, and Noordin (2014), who reviewed the studies conducted on collocations in Iran, acknowledged the scarcity of studies carried out in this regard. Ghonsooli, Pishghadam, and Mohaghegh Mahjoobi (2008) carried out a study on the effect of teaching collocations on Iranian EFL learners’ English writing and found out that it contributed to writing performance. However, no study has compared the impact of using collocations in literary and non-literary contents in the Iranian context. Therefore, this study addresses this issue. More specifically, it has aimed at answering the following question:

1. Does teaching collocations through literary and non-literary contents differentially influence EFL learners’ learning of those collocations?

Method

Participants. The participants of this study were composed of 30 EFL students selected from a larger group of 52 students (24 male and 28 female) learning English at an English language institute in Sanandaj City, Iran. The age range was from 15 to 19 years old. They were all at the intermediate level based on the criteria set by the institute. In other words, the level of the participants had already been assigned by the institute based on the procedure they had been taught, the scores they had obtained from different tests as well as the books they had studied earlier.

Instruments and materials. The instruments used in this study included the assessment materials, the songs of American English File series (Starter and Volumes 1-3), and the tasks and activities employed for each group. The assessment materials were a test of general English proficiency, i.e. the PET test and collocation tests developed by the researchers. The Preliminary English Test (PET) was piloted followed by checking the reliability of the pilot data using Cronbach’s alpha, which indicated that it had a reliability coefficient of .93. Then, the test was administered to the 52 students. The PET included four parts which comprised listening, speaking, reading, and writing. The researchers used only three parts: listening, reading, and speaking. The listening, reading, and writing subsections included 25, 35, and 7 questions, respectively. The listening subsection had 25 points, and the reading and writing subsections each had 50 points. Thus, the total score one could obtain was 75.

The collocation test, which was developed by the researchers as a pre-test to assess the collocation knowledge of the participants, was the second instrument used in this study. It was a 60 item multiple-choice collocation test to ensure their homogeneity regarding collocation knowledge. The newly developed collocation test was piloted prior to the real administration and its items were analyzed by the researchers after the pilot study in terms of item facility, item difficulty, and choice distribution. The items with a discrimination index near 1 were chosen, but the item facility of more items was less than ideal. In the pilot study, the reliability of .96 was obtained. The results of this test indicated that the participants were homogeneous in terms of their collocation knowledge prior to the treatment.

A second test was developed by the researchers to measure the participants’ collocation knowledge after the treatment as the posttest. It was a 60-item multiple-choice test which was entirely based on the collocations that were taught during the treatment. However, five items were omitted after item analysis following the pilot study, after which the test demonstrated a reliability index of .96. The content validity of both collocation tests was insured by submitting them to the judgment of a panel of experts until complete agreement was reached on the items to be kept in the test. The Starter and Volumes 1-3 of the American English File Series as well as three short stories were utilized as the sources of collocations used in the study. The participants were provided with both MP3 songs as well as their photocopied lyrics of the songs in the American English File series. Also, other exercises such as matching and fill-in-the-blank exercises were used.

Procedure. First, the PET test was administered to the 52 students and each one was given a score based on their performance on the test. Out of the 52 students, 37 students whose scores were between one standard deviation above and below the mean were selected as the participants of the study. Next, based on the piloted collocation test, those who answered 20 or less than 20 percent of the 60 items (N=6) were excluded from the study. Besides, one more student was also randomly omitted from the study to form 2 equal experimental groups. Then, the remaining participants (N=30) were randomly divided into two equal groups of 15.

The researchers followed Rieder’s (2002) model which includes three processes helping students to make understanding possible when they encounter a new word in a text. The first process is defined as Enrichment/Focus; in this process, the student identifies the context in which the word was found, helping him/her to classify the word into a category that will facilitate its acquisition. The second process is Abstraction/Integration, in which the identified word is taken out of the context where it was found in order to look for its literary meaning. Then, students elaborate the range of the denotative concept, followed by the integration of the word into the knowledge structures already acquired. This helps one understand and assimilate the complete meaning of the word. Finally, Consolidation/Association, the traditional procedure in which students reassure the word by making connections between the written word and its definition using memorization or practice through different activities.

The study lasted for 12 sessions. The classes were held three times a week, half an hour for each session for teaching the collocations under study. Every session, around 5 collocations were taught. At the beginning of the treatment, the concept of collocation was defined for the students, and the rationale for learning collocations was explained. The learners in both groups were required to guess the meaning of the collocations being taught; if they could not do so, the Farsi equivalents of collocations were given to them.

Next, in the literary group, the participants were asked to use the collocations they had learned in songs and stories and produce sentences containing the collocations in five groups of three students. First, they were given some time to come up with their own example sentences and paragraphs. Meanwhile, the groups were supervised by the teacher to correct errors made by the groups, only in terms of using collocations in the context. While commenting on the examples, the teacher tried to provide the learners with proper examples to help the learners better understand the use of collocations taught through literary contents.

For the non-literary content group, however, the students, in five groups of three members, were supposed to do various exercises such as matching collocations with their definitions, completing sentences with collocations (the list of collocations was not provided), true/false exercises, and filling in the blanks using collocations given in a list. Meanwhile, the teacher, supervising the learners on possible problems, corrected their errors in using collocations. Then, all the exercises with their correct answers were checked by the whole class to make sure that all the students had noted the correct use and format. Finally, both groups took the collocation posttest the day after the treatment had been finished.

The design of the study. As the selection of the participants was based on convenient non-random sampling, the design of the study was quasi-experimental. The instructional treatment with two levels, i.e., collocation teaching contextualized in literary content and non-literary content, constituted the independent variable, and the dependent variable was the participants’ collocation learning as measured by the collocation posttest.

Data analysis. First, the assumptions underlying ANCOVA were checked, including the linearity for each group, the homogeneity of regression slopes between the covariate and the dependent variable for each group, and the assumption of equality of variances. Then, data of both groups on the collocation pretest and posttest were fed into the SPSS, while the pretest scores were defined as the covariate. Next, the descriptive statistics of the groups were computed and a One-way ANCOVA was run to compare the groups’ scores and check any possible differences between the groups’ performance on the posttest.

Results

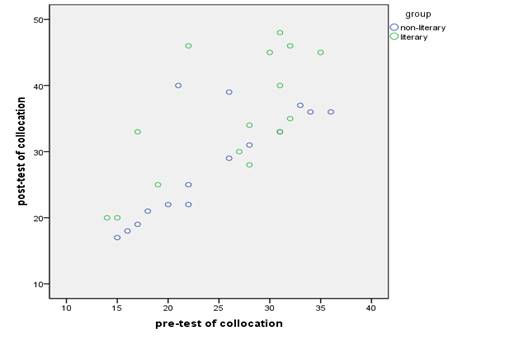

The analysis for the linearity between the covariate and the dependent variable is displayed in Figure 1, below.

The output generated in Figure 1 provided a number of useful pieces of information. First, the general distribution of scores for each of the groups was checked. As the figure shows, there appeared to be a linear (straight-line) relationship for each group. Indeed, there was no indication of a curvilinear relationship. The relationship was clearly linear, so there was no violation of the assumption of the linear relationship. Table 1 below shows the analysis for checking the homogeneity of regression slopes.

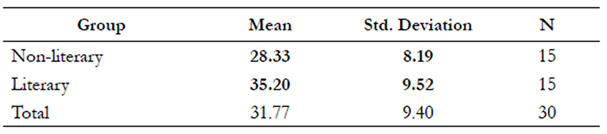

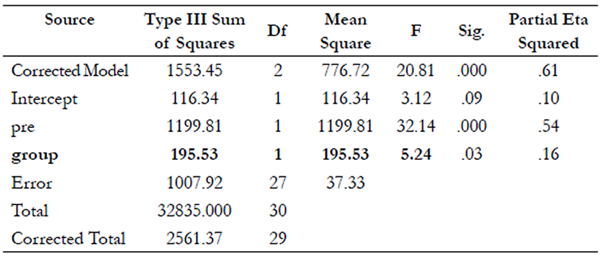

Table 1 Tests of between-subjects Effects for Collocation

a. R Squared= .61 (Adjusted R Squared = .56)

As Table 1 shows, the Sig. level for the Group * Pre interaction was greater than .05, well above the cut-off point (p = .92), which shows that the interaction was not statistically significant and indicates that the assumption of the assumption of homogeneity of regression slopes was not violated. Below, the assumption of equality of variances will be checked, as shown in Table 2.

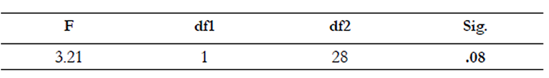

Table 2 Levene's Test of Equality of Error Variances for Collocation

Tests the null hypothesis that the error variance of the dependent variable is equal across groups. a. Design: Intercept + pre + group

The results in Table 2 above indicate that the assumption of equality of variances has been met (p = .08 ˃ .05). After the assumptions of ANCOVA had been satisfied, the One-Way ANCOVA was run to check the inter-group differences in terms of collocation learning. The related analyses are presented in Tables 3 and 4, below.

As shown in Table 3, the means score of the non-literary group was 28.33 with the standard deviation of 8.19, and the mean score of the literary group was 35.20 with the standard deviation of 9.52. The number of participants in each group was 15.Further analyses are presented in Table 4 and these specifically answer the research question in this study.

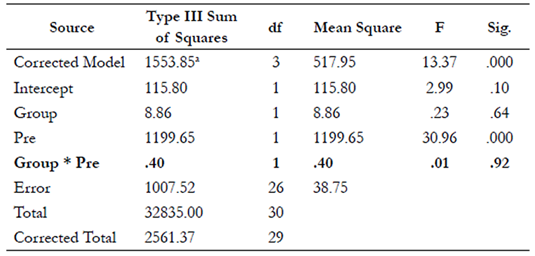

Table 4 Test of Between-Subjects Effects for the Collocation Posttest

a. R Squared= .606 (Adjusted R Squared = 5.77

The results presented in Table 4 show that there was a significant difference between the two experimental groups in their performances on the collocation posttest (p = .03 ˂ .05), indicating that the literary group outperformed the non-literary group on the post-test of collocations. Furthermore, the partial eta squared value turned out to be .16, which signals a large effect size. Hadaway, Vardell, and Young (2002) report three advantages of incorporating literature into EFL classes. The first one is the contextualization of language. EFL learners get familiarized with the use of language in various situations when they read a piece of literature. As students have also to deal with language intended for native speakers, they become familiar with many different linguistic forms, communicative functions, and meanings.

Discussion

With respect to the results obtained from this study, it can be concluded that teaching English language collocations through literary contents in English turned out to be significantly more effective than teaching them through non-literary content. One possible reason for this finding could be the use of authentic materials for contextualizing collocation instruction. Mazzeo, Rab, and Alssid (2003) refer to context as a wide range of instructional strategies designed to link the learning of basic skills and academic or occupational contents by focusing English language teaching and learning on tangible applications in a specific context that is appealing to the students. This is also in line with Bachman’s (1990) argument for the use of authentic texts which enhance better interaction between the learner’s mind and the text. Nevertheless, the other group which practiced English language collocations primarily through fill-in-the-blank exercises is likely to have suffered the shortcoming of being detached from appropriate context.

The results of this study are in line with those in McCarthy (1990), who found that contextualizing collocation instruction facilitated L2 learners’ learning collocations. Furthermore, language input can be not only internalized and comprehensible but also memorable when the language is contextualized by using relevant topics for learners (Bourke, 2008).Moreover, this study corroborates the studies carried out by Shahbaiki and Yousefi (2013) and Pahlavani, Bateni, and Shams Hosseini (2014) who concluded that learning English language collocations positively influenced the ability to understand and translate literary texts in English. However, the findings can challenge the results of studies done by Nation (1994) and Hulstijn and Laufer (2001), who questioned the contextualized method of teaching English language vocabulary for all learners. They argued that learning words out of context through wordlists, doing vocabulary exercises, or even by reading through a dictionary are more useful, specifically for beginners and intermediate levels.

Tosun (2008) believes that the employment of stories in English, particularly authentic animated ones for children, might create not only rich, varied, and contextualized language but might also develop opportunities for the EFL teacher to present and practice this target language through tasks and activities derived from story themes which enable teachers to contextualize the whole lesson. All in all, the findings of this study can be interpreted as implying that the provision of a meaningful context for embedding linguistic elements does not make a difference when only learning grammatical structures in English. Rather, such contextualization seems to foster the acquisition of semantically-oriented linguistic elements such as lexical items and collocations in English. If this is the case, EFL teachers would better look for appropriate contexts for rendering the task of English language learning elements more and more interesting and practical.

Conclusion

Resorting to literature and literary texts can be both facilitating and fascinating to English language teachers and learners alike in that they bridge the gap between contrived instructional materials and activities which might not always attract students’ attention and curiosity. As teaching vocabularies and collocations in English in isolation is not as effective as they are learned in context, teaching typical collocations in English through real and authentic contexts such as literary contents is expected to be more beneficial.

Mere memorization of word lists is both impractical and ineffective. Therefore, this study and the like can open the doors to a new horizon of incorporating the rich repertoire of literature into the confined limits of the EFL classroom. It would possibly enhance students’ motivation to engage in contents which seem to be closer to the reality of their lives outside of the classroom. And this, in turn, will reconcile them with the English language learning activities by removing the pessimism prevalent among EFL learners about the ultimate uses of learning English in an EFL setting.

This study will provide EFL teachers and materials writers with the insight that the use of literary texts in English could be considered a suitable means of contextualization and a feasible alternative to the de-contextualized discrete-point activities often relied on in EFL classrooms.