Introduction

In the following pedagogical proposal, we seek to understand what types of reflections Modern Languages students reveal about educational issues when analyzing artwork within their context. This study was developed at a public university in Colombia with twelve female students majoring in the Modern Languages Program. As part of their core curriculum, the School of Languages proposes that its students become reflective teachers throughout their educational and pedagogical practices. In fomenting the skill of reflective thinking, the hope is that these students will become community leaders, problem-solvers, and transformers of their own educational contexts.

Within the Colombian context, its public universities are usually at the forefront of educational reforms and issues. Because of this, understanding how the students majoring in the mentioned program viewed educational aspects within their university context became important to us as their teachers. The twelve Modern Languages students participating in this pedagogical proposal had not started their teaching practicum. The majority of these students expressed that they did not want to be teachers. For those who had had some experience in the field of teaching, issues like inclusion and violence had created a negative impact on their desire to become teachers. Therefore, this pedagogical proposal was aimed at providing these students with the space to reflect on and dialogue about their current role as students and future teachers.

In order to provide spaces to reflect on educational issues, we, as the participating students’ teachers, developed a pedagogical proposal. This incorporates artwork as the medium by which educational issues could be explored and be the object of reflection. First, we began by exposing students to photography and art pieces that displayed educational issues around the world, such as ethnic exclusion, child labor, and poverty. To follow up, the students analyzed national educational issues in order to gain knowledge to be able to analyze in a reflective manner the murals found within the university. Within most public universities in Colombia, murals are commonly a big part of student life and expression. At the end of the pedagogical proposal, the participating students created then analyzed their own artwork, which summarized their reflections.

For this pedagogical proposal, we attempt to answer the following research question: What type of reflections do Modern Languages students engage in while analyzing the university’s murals and their own artwork?

Theoretical Framework

Reflections. Even before the study, it was evident that the students had a lot to say in regard to educational issues in their current and future context. In many of these cases, the students had not been given the opportunity to reflect on the educational issues surrounding them. A reflection may be referred to as “a generic term for those intellectual and effective activities in which individuals engage to explore their experiences to lead to new understandings and appreciation” (Boud, Keogh, & Walker, 1985, p. 3). In order to differentiate reflection or reflective thinking from other forms of thought, Dewey (1933) provided the following criteria, “(1) a state of doubt, hesitation, perplexity, mental difficulty, in which thinking originates, and (2) an act of searching, hunting, inquiring, to find material that will resolve the doubt, settle and dispose of the perplexity” (p. 12). In other words, the first part of this definition refers to a “mental difficulty” or challenge, such as having a problem. Meanwhile, the second part of this definition is the inquiry.

As Dewey (1933) explained, an inquiry comes about when one tries to find a solution to the problem based on evidence. Ultimately, “Demand for the solution of a perplexity is the steadying and guiding factor in the entire process of reflection.” (p. 14). As mentioned before, part of the core curriculum for Modern Languages students is to be able to reflect on their pedagogical practices in order to become problem-solvers within their educational contexts. Núñez, Ramos, and Téllez (2006) explained that reflections, “allow for the recognition of possible problems in learning among students, with the purpose of identifying and reporting their causes, as well as proposing alterative solutions that lead to changes in the classroom” (p. 111, trans.). Furthermore, Núñez and Téllez (2015) added that “The notion of a problem fosters reflection since teachers’ concerns make them act to alleviate a learning difficulty” (p. 56).

In addition to finding solutions, reflective thinking also involves the ability to build on previous experiences for future reference. Though the Modern Languages students had not started their teaching practicum, it was crucial for them to start reflecting on the experiences they had had as students. Dewey (1933) added that,

Reflection involves not simply a sequence of ideas, but a con-sequence - a consecutive ordering in such a way that each determines the next as its proper outcome, while each outcome in turn leans back on, or refers to, its predecessors. The successive portions of a reflective thought grow out of one another and support one another; they do not come and go in a medley. Each phase is a step from something to something. (p. 4)

Based on the idea that reflection is built upon consecutive outcomes that support each other in the need to find a solution, we took into account two aspects that needed to be considered for the pedagogical proposal: interconnectedness and ownership. By having a similar medium and topic of reflection presented throughout the pedagogical proposal, the students could interconnect reflections that were brought up during the sessions. For instance, reflections on experiences that were discussed during the first session might appear in the students’ artwork in the last session. The second consideration was “ownership of the identified issue and its solution” (Dewey, as cited in Aguirre & Ramos, 2011, p. 172). By allowing students to analyze artwork within their own context, they could take ownership of the problem and solution as it pertained to them and their context.

The role of artwork and reflection. The benefits of utilizing artwork in the classroom are countless. Artwork can help develop observational, thinking, and literacy skills, among many other skills. Through artwork, students can be challenged to think critically and analytically (Barber, 2015). Moreover, the visual arts can develop logic, reasoning, and problem-solving skills (Mackey & Schwartz, n.d.). In a recent workshop titled “Applying Advanced Methods of Reflective Practice in Decision-Making” held by the Dutch Foundation for the Conservation of Contemporary Art, artwork was used to raise awareness for the creative potential and importance of empathy in this process. This practice not only implies critical self-reflection, but also the inclusion of different perspectives in order to overcome biases and create an atmosphere of curiosity and mutual respect (Schäffler, 2018, p. 45). Therefore, reflections on artwork can be a means of creating consciousness in the teaching practice. According to Núñez and Téllez (2015), “reflection is critical in raising teachers’ awareness for personal and professional growth, creating a reflective environment and a positive affective state.” (p. 54)

In addition, artwork could also promote the “inclusion of different perspectives” (Schäffler, 2018, p. 45). As part of the Lineamientos Política de Educación Superior Inclusiva [Guidelines for Inclusive Higher Education Policies] established in Colombia in 2013,

“The understanding of diversity and the inclusion of the community in educational processes as part of an intercultural dialogue are central aspects in the teaching-learning process.” (Ramos, 2017, p. 143) Nonetheless, Ramos (2017) stated that “Although the new document suggests the need to provide pre-service teachers with sufficient spaces for them to learn and reflect on the context, the emphasis is on having future educators teaching classes” (p. 146). To combat homogenization in foreign language programs, as well provide spaces for students to reflect, Ramos (2017)proposed that,

An intercultural perspective in foreign language pre-service teachers’ education understands that education is a social and situated construction. That is to say, it is a dynamic process built not only in the pedagogical space, but in and with society. From the social and situated perspective of education, this should be understood as a process that implies the participation of all society in a dialogue that promotes the understanding and encouragement of consciousness with regard to the cultural, political and economic aspects in which people live their lives. This, in turn, will allow the same community to implement proposals that transform its context. (p. 148)

From this proposal, Ramos highlighted the importance of promoting dialogue that involves the community, which could be connected to Schäffler’s concept that artwork promotes the “inclusion of different perspectives.” In this case, reflecting on artwork that is both “social and situated” could lead to the types of dialogues that promote “consciousness with regard to cultural, political and economic aspects in which people live their lives” (Ramos, 2017, p. 148). As a consequence, students in foreign language programs could reflect on and with their community to find solutions for issues within their context. This, in turn, could help future teachers make changes in their educational contexts that benefit their community.

For this study, we decided to focus on “social and situated” artwork as the medium for which students could talk about and reflect on educational issues. They would start by looking at artwork dealing with international educational issues as an initial practice. In the following sessions, they would focus on reflecting upon local art and their own creations.

Our Colombian context is rich with urban artwork that often represents social and cultural issues. In particular, Colombian public universities often display an array of murals and artwork painted by students as forms of protest and expression. Public universities, like the Universidad Nacional in Bogotá, Colombia, have been the object of studies related to murals and their portrayal of social and political issues. As Rolston and Ospina (2017) explained,

They [murals] are periodically whited out by the university authorities, only to be replaced within a short time by the next generation of political murals. In autumn 2015 the themes tackled ranged from Latin American leftwing heroes such as Camilo Torres and Che Guevara, through the rights of indigenous peoples, to women’s rights, as well as references to memory and justice in relation to the Colombian conflict. (p. 34)

In the case of the university where this study took place, murals are an abundant art form that often express educational issues in addition to the themes mentioned above. Taking the time to reflect on their purpose fosters a sense of reflective practice within the educational context and community.

The creation of artwork can also aid in the process of reflection. Wallas (as cited in Tyler & Likova, 2012, p. 3) described the following experiential aspects associated with the creation of artwork:

Preparation by focusing on the domain of problem and prior approaches to its solution

Incubation by subconscious processes without explicit activity related to the problem

Intimation that a solution is on its way

Insight into a novel solution to the problem

Verification and elaboration of the details of the solution

The abovementioned aspects are similar to Dewey’s problem and inquiry stages of reflection. By having students create their own artwork, they could reflect upon educational issues within their context, while considering possible solutions. Furthermore, by reflecting on their own and others’ individual pieces, they might also take ownership of their own solutions and outcomes. Participation as a group yields and/or can also encourage an intercultural perspective in the classroom when it comes to constructing solutions and taking action for the benefit of the community.

Pedagogical Proposal

Context of the experience. This pedagogical proposal took place at a public university in Colombia, and was carried out with a group of twelve female students from the ages of eighteen to twenty five. The participants are in their fifth and sixth academic semester of the Modern Languages Program of the university. This program focuses on three main aspects (which are related to the fields of education and language teaching), pedagogy, research, and communicative competence. For the most part, students are expected to become elementary or high school Spanish and/or English language teachers after they graduate.

The pedagogical proposal was carried out with the Intermediate English II group. As part of the overall teaching methodology for the course, the communicative approach was employed. This approach views language as the expression of one’s worldview in order to interact and communicate with “the other” and the world. Students enrolled in the course attend twice a week in two-session classes for sixteen weeks in a semester. For the most part, the students come from neighboring cities and towns. They must also travel approximately thirty minutes to an hour every day to get to the university, which demonstrates the commitment they have to their undergraduate studies.

At this point in their learning process, the students are expected to have a high intermediate level of English in order to communicate and teach English as a foreign language. One particularity of this group was that ten out of the twelve participants were unsure about wanting to be teachers. This was unique given the pedagogical focus of the program whose main goal is to educate them to become language teachers after graduation. That is why it seemed essential to provide them with activities that supported them not only as language learners, but also as individuals who are still in the process of constructing themselves as teachers.

Objective of the pedagogical proposal. The main objective of this pedagogical proposal was for the participating students to discuss educational issues within their contexts. In particular, they would reflect on these issues through the artwork found on their university murals and their own creations. The teacher-researchers who directed this experience were the same authors of this paper. Both worked together in order to select and provide the material used in class, as well as guide the discussions regarding the university murals and the artwork created by the students.

The role of the teacher-researchers and students. The main role of the teacher-researchers was to provide students with the space to reflect on the educational issues within their context. We looked to provide a comfortable, trustworthy, and natural environment where they could express their thoughts. For the focus group discussion pertaining to the murals, we began with a general question regarding visual aspects of the artwork. The students would answer the question and lead the discussion to the topics they wanted to reflect on. In some cases, we would also interact with the discussion. Our interaction was meant to stimulate conversation, model speech, and build a rapport with the students. Therefore, “the collective view is given more importance than the aggregate view” (Descombe, as cited in Dilshad & Latif, 2013, p. 192).

The students played the most important role in this pedagogical proposal given that they were the ones providing their reflections while we listened. As no particular student was directed to speak, they could talk and join the conversation whenever they felt comfortable to do so. The students were also the authors of the artwork that they created, and they were free to choose what they wanted to draw based on their reflections about educational issues in their context.

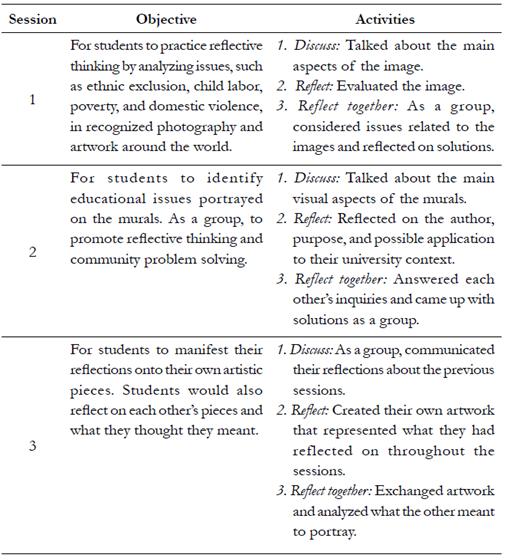

Conditions of the implementation. For this pedagogical proposal, the students engaged in three steps throughout the reflection process carried out in three separate sessions. These steps were: discuss, reflect, and reflect together. The table below outlines the session, objective, and activities implemented in each one of the steps.

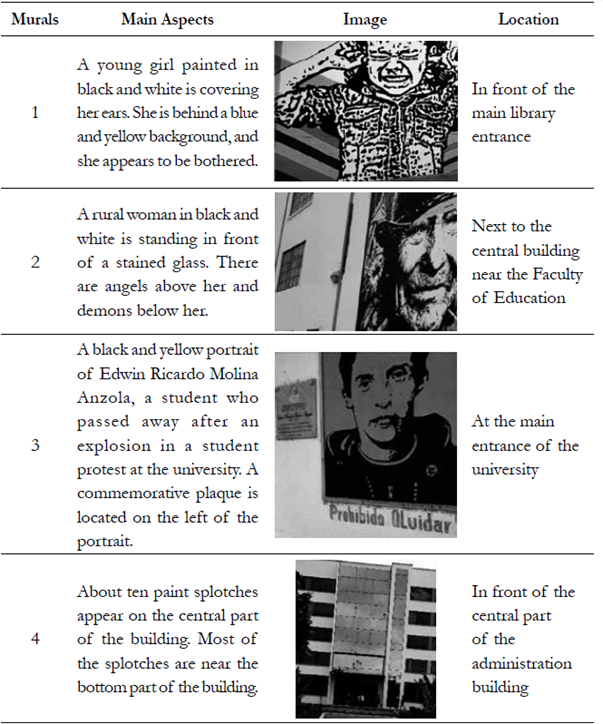

For the second session, we previously selected four murals that the students had to analyze. The location of the murals was also considered given that the students probably walked by them every day on their way to class. It is worth noting that even though the fourth mural might not be considered as such, it is an integral and significant part of the university with an author and purpose. Therefore, we decided to include it as part of the artwork analyzed for this pedagogical proposal. The table below outlines the main aspects of the murals, provides an image, and describes the location.

Data Analysis and Findings

Given that we were working with a particular group and context, the data were collected keeping a case study approach in mind. According to Baxter and Jack (2008), a case study is an approach to research that facilitates exploration of a phenomenon within its context using a variety of data sources. This decision ensures that the issue is not explored through one lens, but rather a variety of lenses that allows revealing and understanding of multiple facets of the phenomenon (p. 544). In order to collect the data, we took field notes before, during, and after each session. During the sessions, the students provided their reflections within focus group discussions, which were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed. In the last session, the students created and commented on their own artwork, which was also recorded, transcribed, and analyzed.

Once all the data were collected, common patterns regarding educational issues and reflective thinking emerged. We used the grounded theory approach to analyze the data, which “involves the progressive identification and integration of categories of meaning from data” (Willig, 2013, p. 70). In the case of the field notes and focus group discussions, we used a system of color-coding to determine patterns present in the information. For the students’ artifacts, we analyzed the artwork for patterns, and we confirmed our interpretation with the students’ comments provided in the focus groups.

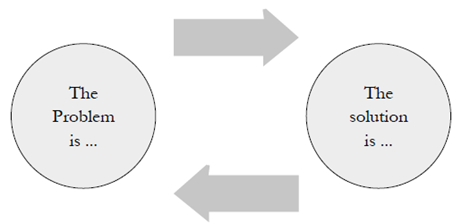

From the data obtained, two main categories emerged based on the educational issues explored in the artwork, which were The Problem is… and The Solution is… As seen in Figure 1 below, the students’ reflections interchanged between identifying a problem and announcing a solution. Additionally, as one student would propose a problem, another might recommend a solution and vice versa.

The problem is... In this category, the focus was the students’ reflections based on educational issues identified either in their university context or in their past experiences as students. One of the murals that produced most of the reflections was the fourth one (see Table 2 above). The students began by first describing the visual aspects of the mural, although we noticed that they immediately moved into describing the problem, as seen in the excerpt below:

I think that students were the subjects that made this painting, and I think that they attacked this building because it is the center of power in the university…So, usually when they state a new rule or a new decrit for the university, students don’t agree with those rules. So, the idea is to block the building and to say we aren’t in agree with those rules. [sic] (Maria Camila, Session 2, Focus group 2)

In this excerpt, Maria Camila described the enforcement of educational reforms as being an educational issue within her context. As she mentioned, students block the university in protest when these new rules are imposed at the university. Moreover, her reflections showed how she took ownership of the issue. As she finalized her statement, she used the word “we”, in which she placed herself with the “students” who do not agree with the enforcement of new rules without their consent.

Another student, Karou, talked about how her position of power is an educational issue in her context. She explained,

I think it’s difficult to talk with him (vice principal) about the situation about our career, but he didn’t listen us because we are a low level. We are students. We are unimportant to him. This is the reason why the spots are low and not high of the building. [sic] (Karou, Session 2, Focus group 2)

In this except, we analyzed how Karou saw herself as a student. Given her reflection that she was unimportant in her educational context, she associated herself with the low spots on the building. This was supported by a statement Nana made about a splotch of blue paint in front of the administration building with the words No privatización [No privatization] written nearby. She added:

The blue of these people and how they differ from us, from them because probably they thought, they think they are in a different stages, so they can do what they want without the perspective of the opinions that we have in our lives. So, it’s about the relation between blue blood and red blood, the real blood. [sic] (Nana, Session 2, Focus group 2)

Once again, we observed how the students reflected on what they saw visually and appropriated it to their own educational issues. In this case, Nana made a distinction between her social group (students) and the other (administration). An interesting point that Nana made is her distinction between blue blood, often associated with royal blood, and “red blood”, which she called “the real blood”. Despite the lack of symmetry in decision making and being disadvantaged by it, she considered herself as a “real” human being and social actor in her context.

Many instances of profound reflection were evident in this focus group discussion. As one of the teacher-researchers reflected:

From my perception, I was really impressed to see that some students have some valuable perceptions about a single colorful spot….I think it was really interesting to see how just by a single image they can say so many things about a single person. (Teacher-Researcher 2, Session 2, Field notes 2)

With the first mural (see Table 2 above), the students were also able to provide their reflections on the current educational issues seen within public schools in rural areas. When they were asked about what they observed in the mural, Camila mentioned the following:

Maybe violence with girls, work, maybe with child work, things like this, maybe bullying. [sic] (Camila, Session 2, Focus group 2)

From her statement, we saw how Camila interpreted the mural given current educational, and even cultural, issues that she was aware of in her context. In the next excerpt, Maria Camila complemented this statement by adding her reflection on rural students’ disinterest in attending school. She stated:

Students don’t want to go to the classes because teachers don’t have the patience to teach them. And they want kids to learn knowledge, knowledge, and only knowledge, and that they repeat all the things the teacher says. So, students don’t want to continue listening to those teachers, and they want to speak. [sic] (Maria Camila, Session 2, Focus group 2)

In this excerpt, we noticed that Maria Camila took what she saw visually and tied it to an educational issue. In her case, she reflected upon traditional methodologies of teaching and the role of the teacher as a transmitter of knowledge and nothing else. It is worth noting that even though Maria Camila focused on the problem at first, she finalized with a reflection on what the student might want to do, which is “to speak”. This is important in the sense that Modern Languages students should be provided with spaces to reflect upon educational issues and the practice of teaching before starting their practicum.

The solution is... The following category emerged as a result of the students reflecting on solutions to the educational issues that were discussed within the sessions. As seen in the literature review, inquiry is the stage that proceeds identifying an issue, in which a solution to the problem is explored. In the excerpt that follows, Karou recalled her own educational experience in a religious institution before starting college.

Here, the nuns only taught me about values and religion and beliefs. But I think that things, important things, like drugs, alcoholic issues, or gays, or things like that are important topics to talk in class. [sic] (Karou, Session 3, Focus group 3)

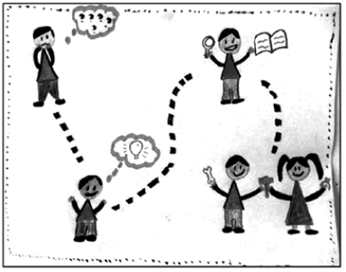

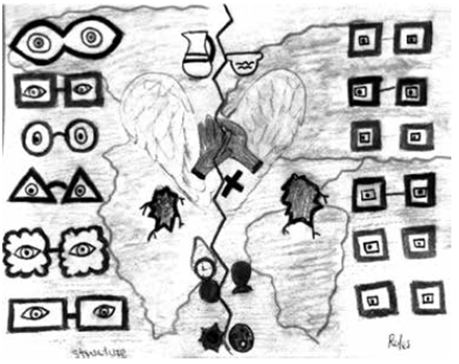

She reflected on the idea that current issues within her context should be taught in schools before students go away to college. This was apparent in her artwork (see Figure 2 below), in which she added:

I consider that in many subjects the teacher just focus on their main topics. For that reason, they forget the importance to teach critical thinking. Wouldn’t it be nice if all students have the opportunity to learn not only about geography or grammar, but also how this kind of knowledge can be integrated with issues in our real context? [sic] (Karou, Session 3, Focus group 3)

We observed how she viewed education as an open door for meaningful learning in terms of not only focusing on content itself but giving students the chance to integrate real issues that are present in their current context. Additionally, she came to the conclusion that critical thinking should also be integrated into the curriculum, along with different life lessons.

Figure 2 Karou’s reflection on the importance of teaching critical thinking. (Karou, Session 3, Students’ artifacts 1).

In Maria’s case, she shared an experience she had in visiting a rural elementary school. In analyzing the first mural (see Table 2 above), her reflections demonstrated how her experience helped her develop empathy and understanding of students’ situations in rural areas.

I saw, for example, a girl, she needed to walk every day for one hour to go to the school, and one hour to go back to the house. I saw in the class that the children feel better in the class ‘cause maybe they have a lot of problems in the family. And in the school, they feel comfortable. [sic] (Maria, Session 2, Focus group 2)

Maria’s reflection is particularly relevant to her role as a future teacher, as some of the students might work in rural settings after graduation. She also realized that going to school might be a haven for some students, which might make her reconsider her role as a nurturer rather than just a transmitter of knowledge.

In terms of the educational issues within their university context, problem solving appeared after the situation had been analyzed in several ways. Once again, Angela invited her social group to think about taking part in the solution after analyzing the fourth mural (see Table 2 above):

As we are students, we cannot try to change the administrative part, but maybe, if we are as a resistance, maybe can be listened in some way. But if we are as a passive students, we cannot say nothing, and they never listen us, and the situation at the university cannot change never. [sic] (Angela, Session 2, Focus group 2)

Interestingly, this statement came after an analysis of the spots on the administrative building and how they might represent “a few students that fight” (Karou, Session 2, Focus group 2). So, we saw how one idea helped build another, which eventually provided a solution. In this case, the solution was to work together as a force of resistance in order to be heard. The idea of constructing solutions together is supported by the teacher-researcher’s field notes:

They were all able to build different and multiple perspectives and were able to scaffold on each other’s ideas. (Teacher-researcher 1, Session 2, Field notes 2)

The idea of working together and building on each other's ideas was also evident in the students’ artwork. We saw a common theme associated with problem solving and finding solutions (see Figures 3 and 4 below). As Figure 3 showed, there was a person with a question who sought a solution. After searching for the answer, and with the help of someone, he found the tools to solve the problem. In Figure 4, different kinds of people were working to put the pieces of the puzzle together.

Figure 4 Different people coming together to solve the puzzle. (Maria Camila, Session 3, Students’ artifacts 1)

In analyzing her partner’s artwork, Tatiana had the following to say:

…we arrive to a specific think, that is to give a solution to bring help to different people. [Sic] (Tatiana, Session 3, Focus group 3)

The idea of finding solutions with different perspectives also came up in several other reflections, such as that provided by Alejandra, who mentioned the following regarding Figure 5 below:

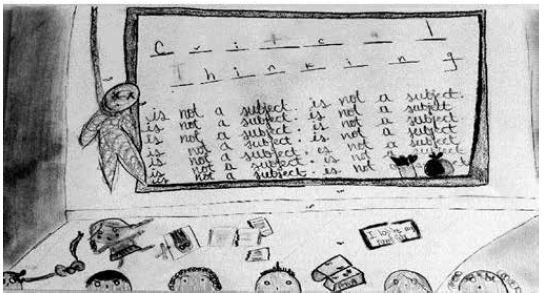

So, the people who follow rules, they see, they accept the same problem with the same glasses. They don’t go beyond that to analyze a problem. But people who see the problem with different glasses, with different perspectives because they have different thinkings about the same problem. [Sic] (Alejandra, Session 3, Focus group 3)

In Figure 6 below, Maria reflected on the importance of having one’s eyes open to new experiences. According to Maria, when the eyes are open, they can see many perspectives. Meanwhile, when a person is close-minded, his or her eyes are closed as well. For that reason, he or she can only see darkness.

Through their artwork, the students primarily reflected on the importance of working together to find solutions. In particular, they discussed the significance of viewing a problem from different perspectives. The use of colors, eyes, and multiple people helped show this idea.

Conclusions and Pedagogical Implications

The main objective of this pedagogical proposal was to explore the types of reflections Modern Languages students had when analyzing artwork in their university context. From the data collected, we noticed that students began by analyzing the visual aspects of art, whether it was the murals or personal art pieces. This was immediately followed by a focus on the issue. As the discussions continued, the students worked together to expand on the problem from different perspectives. Moreover, they also suggested solutions to the problem, which relied on helping each other to solve the issue.

At the fourth mural, students primarily discussed the problem with educational reforms being imposed on students without their consent. In the case of Maria Camila, she took ownership of the problem by including herself as a person affected by the issue. Similarly, Nana and Karou talked about their positions of power in relation to that of the administration and how their status as students affected their education. When discussing issues related to rural, public, and traditional education, the students relied on previous experiences. One thing that marked these reflections was that the students were more willing to come up with solutions. Though they had little or no teaching experience, it was evident that their reflections showed an understanding of empathy toward the student. Both Maria Camila and Camila also questioned the role of the teacher as just being a transmitter of knowledge.

In the second part of the reflective process, we considered the types of solutions the students provided. For the most part, they talked about the importance of working together to solve the puzzle. Their artwork showed this through the use of puzzle pieces and multiple people. Another commonality was the use of colors to show diversity of thought, as well as eyes to show different perspectives. As Alejandra reflected, “people who see the problem with different glasses, with different perspectives.” Overall, the students demonstrated two main aspects when it comes to problem solving, which were working together yields a diversity of perspectives.

Engaging students’ in reflective thinking is not a novelty within the Colombian context. There have been significant benefits reported when it comes to reflective thinking and students in the field of language education. As Cote (2012) concluded on reflective thinking and foreign language student teachers, “they were better able to question the types of materials used, better balance the allocation of time to class activities, and implement sudden changes on the students’ particular attitudes and reactions” (p. 33). Likewise, Núñez and Téllez (2015) commented that “Reflection also serves the purpose of creating a reflective learning environment that engages teachers in appropriate and relevant activities and motivates them to ponder their pedagogical and research practices” (p. 67).

Though the Modern Languages students had little to no experience in teaching, they were able to reflect on issues and solutions related to their educational context. As seen in the findings, the students leaned toward helping the student out and taking on nurturing roles in the classroom. Furthermore, having the space to talk about issues with their peers and teachers also motivated them to consider solutions to possible issues that could be encountered in their teaching practicum and educational contexts. Therefore, it would be useful to engage students, even if they have not started their practicum yet, in reflective thinking. They could begin by practicing on educational issues related to their context so that when the time comes to teach, they will be better prepared as reflective thinkers and social actors in their communities.