Introduction

If a doctor, lawyer, or dentist had 40 people in his office at one time, all of whom had different needs, and some of whom didn't want to be there and were causing trouble, and the doctor, lawyer or dentist, without assistance, had to treat them all with professional excellence for nine months, then he might have some conception of the classroom teacher's job. -Donald D. Quinn (The importance of teaching, 2004).

Classroom management (CM) is that subjective and almost magical element that allows teachers to either succeed or merely survive in a class, as most teachers might have experienced at least once in their professional practice. Some teachers seem to "own" the magic, while others struggle with managing conflict, assuming their authority role, or managing time. How can this be explained? Let us take a look at this idea: "We often hear educators say that teaching is both an art and a science. I take this to mean that teaching is basically a subjective activity carried out in an organized way." (Kumaravadivelu, 2003, p. 5) This statement sums up the multidimensionality and complexity of the teaching profession. CM is the perfect example of how each teacher brings their own assumptions and feelings to objective tasks like planning and executing lessons, sometimes unsuccessfully.

Foreign language (L2) teachers, novice or otherwise, struggle with stressful situations, including those associated with classroom management such as handling large classes or working with limited materials (Renaud, Tannenbaum & Stantial, 2007; Rhoades, 2013). This struggle may negatively impact L2 teachers' permanence in the teaching profession (Borman & Dowling, 2008; Lewis, 2009; Smith & Ingersoll, 2004), their students' motivation and involvement levels (Wright, 2014), and in general, the amount of learning that takes place in a classroom. Supporting novice L2 teachers is important because their well-being and their effectiveness1 in handling the classroom ultimately affect learners. Thus, the goal of this article is to outline a characterization of CM, its dimensions, and set of initial ideas to approach L2 teaching with more confidence. It is expected that these ideas will benefit not only novice L2 teachers, but also experienced ones. Even though learners cannot be removed from the teaching/ learning process, this article focuses on articulating issues about CM that novice L2 teachers need to navigate toward as they permanently construct their professional identity.

Classroom Management and Novice Teachers

Expert teachers are more sensitive to the task demands and social situation when solving pedagogical problems; expert teachers are more opportunistic and flexible in their teaching than are novices... expert teachers have fast and accurate pattern-recognition capabilities, whereas novices cannot always make sense of what they experience (Berliner, 2004, p. 201).

Berliner (2004) refers to instruction, but flexibility, responsiveness and metacognition can also be applied to CM. The relationship between CM and pre-service or novice teachers has been profusely researched in the last four decades in general education, educational psychology and foreign language teaching (Cyril & Raj, 2017; Hart, 2010; Macias, 2018; Pineda & Frodden, 2008; Quintero & Ramirez, 2011; Veldman, Admiraal, Mainhard, Wubbels, & Tartwijk, 2017). These authors coincide in the idea that setting up an adequate work atmosphere and dealing with challenges in the classroom is a sensitive and, at times, difficult area for every teacher, particularly for novices (Caner & Tertemiz, 2015; Fowler & Sarapli, 2010; Lewis, 2009; Macias, 2017; Macias & Sánchez, 2015; Marzano, Marzano & Pickering, 2003; Quintero & Ramirez, 2011; Sánchez, 2011a, Sánchez, 2011b; Pineda & Frodden, 2008; Sieberer-Nagler, 2016). Given its influence on learning outcomes, CM could be more prominent, and instruction on it could be more explicit in L2 teacher education programs, conferences and workshops for professional development. Many have voiced this need in journals (Macias, 2018; Pineda & Frodden, 2008; Quintero & Ramirez (2011), post-observation conferences, methodology courses, and blog posts (e.g., https://tesol1and2.wordpress.com/classroom-management-task/ ). In informal comments concurrent with research, student-teachers and novice teachers expressed feeling confident about their L2 communicative competence and their teaching skills (e.g., lesson planning, syllabus design), but CM was perceived as a significant challenge. An accurate impression as they "from the very first day on the job must face the same challenges as their more experienced colleagues, often without much guidance from the new school or institution" (Farrell, 2010, p. 436).

It sounds reasonable then, to promote metacognition about the theoretical and practical aspects involved in CM among novice teachers. Why? First, it helps them establish clear roles in the class and leads learners to engage in the activities planned for a lesson with less resistance. Second, if novice L2 teachers handle the planning and execution of a lesson effectively, they will be able to make the most out of the available time and resources regardless of their teaching conditions. Third, the lack of CM skills might negatively affect the roles novice teachers assume, their self-esteem, their sense of self-efficacy, and, ultimately, their permanence in the profession. Fourth, it does not matter how strong the theoretical background of an L2 teacher is, or how fluently s/ he speaks the language; if the environment s/he has created is not conducive to learning, the fundamental nature of teaching is lost. Fifth, if novice teachers enter the practicum with a basic set of principles and practices, they will have more confidence in initially approaching teaching (Sánchez, 2011b). True, CM improves with time and experience, but novice teachers cannot afford the luxury of teaching and taking their time to get a grasp of classroom dynamics. They must start teaching as part of their practicum whether they feel ready for it or not, something that is not without its consequences. As Ingersoll and Strong (2011) point out, between 40% and 50% of teachers leave the profession in the first five years adding that,

Pre-employment teacher preparation is rarely sufficient to provide all of the knowledge and skill necessary to successful teaching, and that a significant portion can be acquired only while on the job (see, e.g., Feiman-Nemser, 2001; Ganser, 2002; Gold, 1999; Hegstad, 1999). Hence, this perspective continues, there is a necessary role for schools in providing an environment where novices are able to learn the craft and survive and succeed as teachers (pp. 201-202).

One initial step in supporting novice teachers' knowledge of CM is exploring its different definitions and the elements associated with it.

Understanding Classroom Management

CM in second/foreign language (L2) teaching is interpreted from diverging perspectives, something that may obscure its meaning. These perspectives go from conceiving CM as a synonym of discipline, to seeing discipline as one sub component of CM. CM could also be something as broad as the teacher's role in a class (e.g., motivator, facilitator), or something as specific as arranging chairs in a certain way to foster interaction. For some, CM is a teaching skill that serves to create, maintain, and if the circumstances require it, reestablish the classroom atmosphere to foster teaching and learning (Brophy, 1986), while a broader view establishes it as "...a wide-array of proactive, well-established, and consistent techniques and practices teachers employ to create an atmosphere conducive to learning" (Johnson et al., 2005, p. 2). The latter view is broader in nature than discipline and encompasses planning, monitoring, transitions, and the sequencing of classroom tasks (Latz, 1992). A more recent and simplified definition sees it as "a well-planned set of procedures and routines for avoiding problems, and having a plan in place for when misbehavior does occur" (Rawlings, Bolton & Notar, 2017, p. 399). As the authors explain, this definition goes beyond early definitions that focused on the teachers' behavior, not student behavior and on the idea that CM fostered instruction. One idea agreed upon is that CM encompasses how teachers deal with multiple issues inside the classroom simultaneously: from keeping learners on task, to changing the physical environment of the classroom to foster learning, to handling misbehaving learners, to deciding how to transition into the next activity, all while working with content and assessment (Brown, 2007; Harmer, 2007; Scrivener, 2011; Ur, 2012). All these require teachers to think on their feet and think metacognitively (i.e., being aware of what they are doing and why they are doing it).

I contend that although practical hints for CM can be helpful to quickly address novice learners' concerns, CM is more than that. CM refers to the teachers' dynamic decision-making about learning, and their emotionally-mediated reactions toward disruptive situations in the classroom. These reactions reflect the teachers' beliefs about effective learning and teaching, their theoretical background regarding how an L2 is learned and the teachers' teaching experience, problem-solving and planning skills, all of which results in successful or unsuccessful learning conditions in the classroom. This idea concurs with those of Pineda & Frodden, 2008; Sánchez, 2011a; Quintero & Ramirez, 2011).

Even though teaching is both an art and a science, and is always affected by teachers' idiosyncrasies, teachers need to approach CM as a task that requires planning and a basic knowledge of its components instead of as an unplanned reaction guided by mere intuition. Getting acquainted with extant research, reflecting and writing about these issues, and analyzing examples of exemplary teaching are initial steps in that direction. Further knowledge is gained by acknowledging the challenges and consequences of not handling the dynamics of the classroom, something that has been researched from different perspectives, while highlighting the prominent role of CM in the classroom (Landau, 2001; Latz, 1992; Yerli Usul & Yerli, 2017). For some, CM is the most essential issue in a teacher's day-to-day professional practice (Wright, 2005), the most valuable set of skills instructors can have (Landau, 2001), or one of the most difficult responsibilities that teachers deal with in the classroom (Caner & Tertemiz, 2015).

Research is a healthy way to understand the scope of CM. Future research avenues may revolve around isolating the elements found in the dimensions of CM and observing the effects of an intervention (e.g., intervening in class size by dividing a class into two groups and comparing the classroom dynamics of the smaller groups versus those of an undivided one); working with novice teachers to understand, from their narratives, their conceptions of CM and how these evolve, or observing the effects of explicit instruction on classroom management in a group of pre-service teachers versus no additional instruction.

Having outlined a definition for CM and its relevance, we can now discuss its dimensions.

The Dimensions of Classroom Management

The divergence observed in the definitions of CM is also found when advancing its components. However, it is possible to find recurring topics in the literature: effective classroom management relates to teachers, students and classroom atmosphere, and these can be stated as "(1) rules and procedures, (2) disciplinary interventions, (3) teacher-student relationships, and (4) mental set". (Marzano, Marzano & Pickering, 2003, p. 8)

Table 1 presents novice teachers with a quick glance at recurrent components of L2 classroom management (Brown, 2007; Harmer, 2007; Scrivener, 2011; Ur, 2012). The table provides teachers with an inventory of the elements included in CM and shows that the interaction of a number of elements may enhance or hinder the teaching and learning process. For instance, novice L2 teachers might underestimate the effect of acoustics or board use on their lessons. This table might help them visualize the wide array of elements that could disturb instruction.

Table 1 Classroom Management Components

Note: Adapted from Brown (2007), Harmer (2007), Scrivener (2011), and Ur (2012)

It is important to clarify that some of these components are particularly permeated by context: Teaching under adverse circumstances reiterates the role of subjectivity in teaching and deserves some comment. For instance, the definition of "large class" is subjectively and culturally defined (Brown, 2007). The challenges for teachers in Colombia as reported by Macias (2018) are not different from those reported in other settings, but similar circumstances may be perceived as challenging depending on the context. For instance, working with 40 students is not uncommon in some EFL settings, but in other contexts a group of 25 learners may be too large to handle. Other issues include: grouping learners with different L2 proficiency levels or dividing them, making decisions about the selection of content, and deciding on suitable methodology for the course.

Discipline, one of the elements included in classroom management, is also context-dependent since cultural expectations vary. In some contexts, a certain amount of noise is acceptable since the goal is that learners use the language communicatively and it is not problematic, whereas other contexts will require teachers to keep students quiet all the time. Discipline does not have a unidimensional definition, but as Ur (1996) suggests, if in a classroom a) learning is taking place, b) teacher and students cooperate to achieve a common goal, c) students are motivated to engage in the tasks planned by the teacher and d) the lesson is going as planned, then discipline is present. Finally, teaching roles and styles are also mediated by culture. Students from different backgrounds (e.g., Colombian, Chinese, and American) may have diverging expectations on classroom dynamics, on how explicit teachers are in the provision of feedback, error correction, and how they are supposed to handle instruction and assessment. These expectations might affect how teachers are perceived and how students relate to them. In one context, a teacher might be perceived as authoritarian or rude, while in a different context the teacher is perceived as strict.

I consider classroom management to involve three dimensions related to the components already described, but more comprehensive in nature. Those dimensions are: the teacher, the planning, and the environment. The first one includes teachers' attitudes, the roles they may assume, and the decisions they make before, during, and after the lesson, all of these in order to foster the best possible conditions for language learning. The second dimension is planning, including course planning, lesson planning, classroom management planning (e.g., establishing routines to give learners a predictable framework), and even planning how to react in certain challenging situations. The third dimension is the environment which has to do with working on the constraints of the classroom and creating an atmosphere of cooperation, respect, and well-being (i.e., what Brown, 2007, calls energy) so that tangible elements as materials, equipment, tasks, and tests can be used effectively and foster learning.

These dimensions address potential sources of CM problems prevalent in the reviewed literature for this paper. These dimensions are more suitable being managed by the teacher and more likely to be addressed with planning and awareness.

Successfully Managing the L2 Classroom

CM might not be rated as one of the strongest stressors for L2 teachers (Lewis, 2009) if teachers had at their disposal some adaptable guidelines for facing it. Although teachers can find some straightforward, practical advice in books and websites such as Edutopia, Teaching Channel or The Teacher's Guide; in the long run, it is desirable to undertake teaching as an activity led by principles (Jackson, 2009) and reflection (Richards & Lockhart, 1996). Thus, situations like student misbehavior will not be read as a challenge to teachers' authority, but as a deviation from the class principles. Unfortunately, some educators may not be that objective, leaving CM to be guided by perceptions of what is acceptable or not. In fact, sometimes teachers may objectively know what to say, but this will be different from what they do:

Ask around and you'll likely find that most every teacher that you question believes that he or she is an effective classroom manager, including ones who clearly struggle. Disconnect between perception and reality occurs at times because even less-effective teachers can point to certain maxims that they accept as the foundation of quality management, and identify the specific things that they do to carry them out. (Englehart, 2012, p. 70)

Consciously attempting to make the connection between what you say and what you do needs to be kept in mind to approach CM according to contextual demands. Coherence is important: what you say should match what you do. To be coherent in their professional practice and create a sense of predictability in their lessons, teachers need to determine which role they want to play, what their beliefs are, how they match their planning to the actual lesson execution, and how their class interactions enhance learning. In short, we need to be reflective (Richards & Lockhart, 1996).

Next is a set of perspectives which are connected to the three dimensions of classroom management (i.e., the teacher, the planning, and the environment), and which can contribute to managing a classroom. Let us begin with the person in charge of managing all the moves in the classroom so the conditions facilitate learning.

The teacher. CM should not be based on improvised reacting, but on being proactive. That is, L2 teachers need to have a plan when they enter the classroom and this plan begins with themselves. L2 teachers need to be knowledgeable about the theoretical background of their profession, including but not limited to, foreign language methodology, second language acquisition (SLA), research methods, and instructed second language acquisition (ISLA). In addition to this specific knowledge, L2 teachers also need to support their practices with findings from general education. For instance, educational psychology, particularly group processing (Schmuck & Schmuck, 2001), can be useful in understanding the dynamics of classrooms and providing principles for classroom management. In this light, students are not seen as individuals, but as a group that behaves and interacts in unique ways, and which exerts influence on each other and whose goals, roles, and emotions affect, among other things, classroom climate, and consequently, CM. A strong background can help L2 teachers make evidence-based decisions, shape their plans for CM, reflect on their past actions, and if needed, introduce modifications to enhance their future actions, but again, a good plan involves action, a deliberate attitude, and a sense of agency on the part of the teacher towards the craft of teaching and towards managing the class. As it has been suggested,

A major theme of classroom management research is that teachers who are effective classroom managers demonstrate an ethos of "warm demander," that is teachers signify to all that they care for their students and simultaneously hold high expectations for their academic, social and overall continued success (Pool & Everstone, 2013 as cited by Salvosky, Romi & Lewis, 2015, p. 57).

This means that a commanding, authoritative presence is important. How do we achieve it? Again, how do we own the magic? There are simple things L2 teachers can do: Be aware of your posture and how you address your audience. Be comfortable with being the authority in the classroom and show that you enjoy teaching, be in touch with your emotions as you teach and try to read your students' reactions to what you are doing. Also, make sure your students can hear you and see you clearly, which means you need to be as mobile as possible, even if the layout of the classroom does not allow you to reach every corner of it. It is important not to hide behind your desk or just stand next to the board. Mobility will help you do different things: notice who is absent, monitor what students are doing, keep them on task, attentive (no one speaks when the teacher is standing right next to you!), and deal with little disruptions (e.g., learners are not using the L2) without drawing too much attention to the issue.

A final word about the role of L2 teachers has to do with avoiding self-,0(J defeating attitudes: not every student likes the class we teach. Students do not always have to behave perfectly, and L2 teachers do not need to be in total control of the class all the time. Unrealistic expectations will leave L2 teachers feeling stressed, frustrated, and threatened by learners (Macias, 2018), even resenting their students. Instead of taking things personally and responding to feelings only, a metacognitive attitude will allow L2 teachers to respond adequately and make positive choices (Lewis, 2009). L2 teachers need to monitor their reactions and attitudes during and after the class, because as Lewis and Lovegrove (1988) (as cited in Lewis, 2009) conclude, students "may become less interested in subjects taught by teachers who display anger, mis-target and punish innocent pupils, and don't give warnings before issuing punishments" (p. 28).

Classrooms, however, are unpredictable; they are complex and under constant reshaping and construction thanks to the interaction between L2 teachers and learners, the contributions of learners, and the context. Not everything can be solved solely by the teachers' attitude and presence, but planning and awareness can contribute to fostering learning and positive classroom dynamics.

Planning classroom management. The perfect plan would be one that completely avoids disruption in the classroom, but again, that is not realistic. The next best thing is creating a tight lesson plan following the coherence, variety and flexibility principles (Jensen, 2001), and including a clear goal, explicit transitions among stages, and specific roles for learners in each stage of the lesson. It should suffice to prevent difficulties, and potential disruptions could even be noted in the lesson plan, along with the possible alternatives to solve them. Over preparing is strongly suggested, especially for novice L2 teachers. Getting materials ready beforehand (e.g., hand-outs, photocopies, movies, audio files), knowing how the equipment works, and deciding how learners will interact/ work at different points in the lesson (e.g., group work, pair work) will enhance teachers' confidence and keep the pace of the class. Two important elements to highlight inside planning are routines and conflict strategies.

Establishing routines. Routines are part of planning and teacher preparation, and can contribute to creating a predictable environment and safe spaces where learners can practice the L2 (e.g., start every class greeting in English and getting two students to provide a one-minute oral report on an interesting piece of news). The benefits of routines include decreasing the likelihood of teacher stress and teacher burnout, the prevention of chaotic classroom environments, the establishment of a culture of respect and care inside the classroom, and effective time management (Rawlings Lester, Bolton Allanson & Notar, 2017). Routines need to be determined by the teacher and included in lesson planning. These routines need to have a clear purpose. This will help teachers think about transitions, required materials and featured language skills (i.e., listening, speaking, reading, and writing). A good example of routines for beginner L2 learners is classroom language. Classroom language refers to the vocabulary, commands, and expressions used in the lesson. When beginners do not understand what they are being asked to do, they might start talking to others or be unable to follow the task. Classroom language could be the focus of the class for at least two or three weeks. At the beginning of each class, teachers can establish a routine for practicing, recycling the expressions previously learned and introducing new ones until learners are familiar with the language the teacher uses to direct attention (e.g., I want you to just listen to the story), use materials such as textbooks (e.g., open your books to page X), or organize a task (e.g., I want you to get in pairs and find the differences in the picture). Similar routines can be planned for the last minutes of the class (e.g., a vocabulary game can be played to reinforce contents) when learners tend to be tired, become disruptive, and/or do not want to work.

Dealing with conflict. Having a plan regarding CM also means knowing how to react when disruptions do occur despite careful planning. When the problem is starting to manifest itself, teachers can deal with the disruption quietly. If someone is playing with a phone, the teacher can stand next to the student, call him/her by name and ask him/her to pay attention. Do not overreact (e.g., crying, yelling, storming out of the classroom - remember: you will have to come back to that same classroom eventually). Avoid begging or playing the victim (e.g., I'm too young, I'm not the main teacher, or I do not have experience). Avoid taking things personally, or using threats you do not intend to follow up on. In short, keep cool; keep your poise (Brown, 2007). Remember that "teachers who lose their tempers and yell at such pupils, or attempt to quell their misbehavior by using cutting sarcasm, are likely to escalate the conflict" (Lewis, 2009, p. 22).

When conflict has manifested itself, there are three ways to deal with it: explode, give in, or negotiate in a way the learners cannot refuse (Ur, 1996). Let us elaborate on these options.

Explode. Exploding does not refer to being aggressive, sarcastic or offensive, but rather to being assertive and giving a brief, loud, firm command; telling learners what you expect them to do at that moment. This might be followed by a quick reminder of the rules they need to follow in your class.

Give in. Imagine that your students get too involved playing a vocabulary game and do not want to go on to the next activity you have planned. Do not get engaged in a confrontation with the whole class as you will spend time arguing and you will always lose face. Give in and allow them to keep on playing, but make sure they know they need to compromise. Tell them they will have to do the activities you had planned as homework, or that they will research the topic in small groups so the class does not fall behind.

Negotiate. In the final option, teachers can use three strategies: postpone (e.g., I can give you 20 minutes tomorrow to discuss the problems you have had with the project. Right now, let us continue with the task...), compromise (e.g., the date for the test will be kept, but I will post the possible questions on the class blog), or arbitrate (e.g., since we cannot reach a decision, you will vote on the deadline for the presentation and the whole class will accept the result).

A caveat is needed here: If you use these brief outbursts too often, give in too often or allow learners to make decisions too often, these strategies will lose their effectiveness. Use your judgment and remember that prevention is better than cure.

The environment. The final component of classroom management discussed here is the classroom itself and it is relevant to include it since it influences the effectiveness of teaching and learning. Some prevalent characteristics of classrooms that might be a challenge include the organization of desks in rows, having a separate space or even a raised platform for the teacher, and having the board as the only available material (Wright, 2005). Although there is not much that L2 teachers can do to actually change the physical features of the classroom (acoustics, number of desks or equipment), L2 teachers can stand up and interact with others, walk around and get closer to the learners instead of directing the class from the platform. Also, L2 teachers can ask learners to bring one large picture taken from a magazine to create a picture file that can later be used in pair work or in oral tests. Other elements to consider include getting things ready before learners come in the classroom, and asking them to hand things out instead of wasting time going from desk to desk handing papers out. If L2 teachers are using technology, they need make sure the classroom has electrical outlets, and that the whole class can see or hear what has been prepared. Also, L2 teachers should erase the board, and make consistent use of it; for instance, writing key vocabulary on the right side, new information in the central part, and the date and homework reminders on the left side (Brown, 2007).

One aspect that influences classroom management and the environment, although it is not a physical entity per se, is time.

Time. Similar to class size, time is a relative concept. Some L2 teachers may feel that teaching two hours is too long, while others are comfortable teaching for three hours or more. Again, lesson planning is key in preventing time management problems such as finishing the class without having achieved the set goal, making learners write a paragraph they did not get to read to the class or rushing to do two or three activities in ten minutes. Specific timing is needed for practicing, for assimilating the new vocabulary or form introduced by the L2 teacher, to engage in routines and to assess the outcomes of the class. Depending on how L2 teachers shape their lesson plans, there could also be time for checking homework or clarifying doubts. L2 teachers' decisions about how to use the allotted time will also help them choose and prepare materials accordingly. For example, it is not uncommon for novice L2 teachers to find themselves taking ten minutes out of a 45-minute class to set up the equipment for watching a 5-minute video. Time is a valuable asset for teachers, students are quick to notice when a teacher is either killing time because they ran out of activities, or desperately trying to cram everything when the first fifteen minutes of the class were spent doing small-talk. We structure our lives around time and teaching should not be an exception. Time, same as CM, can be a teacher's friend or foe.

The intention of this paper is not to prescribe or homogenize classroom management practices. Nothing guarantees that a strategy will always work. However, after 20 years as a teacher educator, I have learned that novice teachers appreciate having a scaffold before walking into a classroom. As Macias (2018) claims, "research on classroom management in foreign language education has also focused on providing ways or mechanisms to help foreign language teachers reduce the impact of classroom management issues in their courses" (p. 162), and this should be a positive thing.

Conclusions

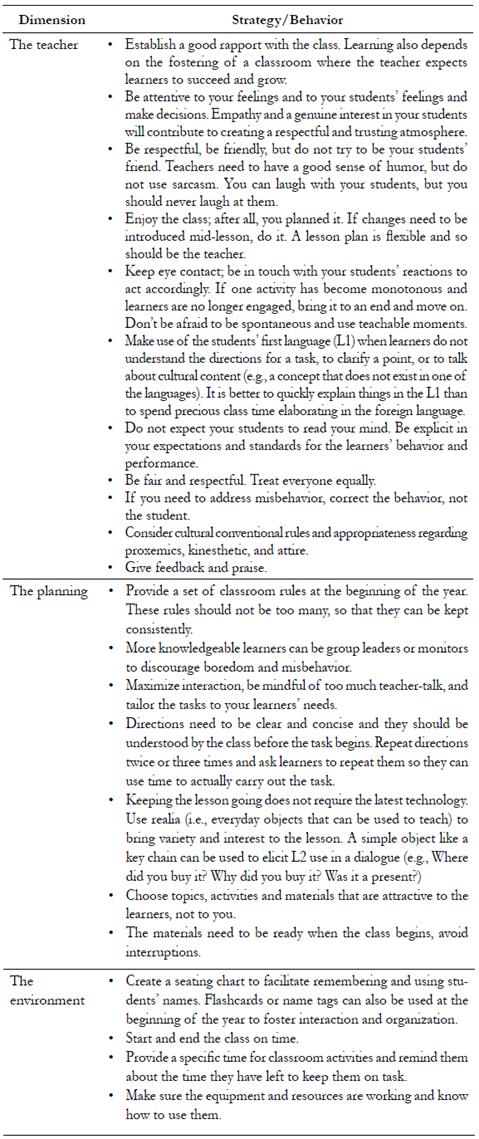

It has been suggested in this article that CM is to be assumed as a reflective and planned activity rather than one guided by impromptu reaction, and that teaching is supported more effectively by principles than by a one-size-fits-all set of rules. However, this article looks to provide novice L2 teachers with practical ideas to enhance their initial encounter with teaching, thus the following compilation of ideas of authors addressing each classroom management dimension (Brown, 2007; Castellanos, 2002; Quintero & Ramirez, 2011; Renaud, Earlier in the article, it was suggested that CM is challenging for novice L2 teachers. The challenge is always there, even for L2 experienced teachers. That is why the decision-making of teachers is dynamic: A perfectly planned lesson can go wrong, and a disruption can be transformed into a teachable moment. Paradoxically, L2 teachers' job consists of expecting the unexpected and being ready for things that cannot be anticipated when they walk in the classroom. What novice L2 teachers need to remember is that being comfortable in their own skin, good planning and knowing how to work with the environment will contribute to facing those challenges more effectively. In the long run, being attentive to what works and what does not in the classroom, and making decisions to appraise and address the situation (i.e., being metacognitive) will lead L2 teachers to effective classroom management. As experience is gained, CM will likely become their ally. In sum, be confident, be knowledgeable, be organized, be flexible, be tidy, be reflective, and be ready.

Table 2 This summary gives novice L2 teachers the idea of the multiple tasks they will have to control in the classroom, and they can take away some preliminary strategies that facilitate approaching these tasks.

Note. Adapted from Brown (2007), Renaud, Tannenbaum, and Stantial (2007), Ur (1996; 2012), Quintero & Ramirez (2011), and Wright (2005).