Introduction

The Chilean curriculum for teaching English as a foreign language (EFL) suggests that English language teaching should focus on the development of macro skills of listening, writing, reading, and speaking in order to promote students' ability to communicate fluently in this language (Ministerio de Educación de Chile, 2015). Most of the English Language teacher education programs in Chile have begun to train pre-service teachers in methodologies to plan lessons under these criteria of the national curriculum. This training, thus, should follow a communicative-based approach. Despite these directions, EFL lessons in Chile still seem to be based on traditional approaches for various reasons. For instance, English language teachers experience more difficulties having to do with the language. These are related to motivational aspects (Glas, 2013), linguistic deficiencies in students' L1 (Díaz et al, 2008), and contextual difficulties, which make it even harder to comply with the Ministry requirements. Therefore, teachers tend to opt for traditional teaching practices (Yilorn & Acosta, as cited in Yilorn, 2016, p.107).

In view of the above scenario, early instances of reflection should become pivotal for raising pre-service awareness about the new trends of teaching EFL (Farrell, 2013). This means that one road to be aware of new approaches to teach English, and actually being able to reconsider them during the process of teaching, is through reflection. In fact, Second Language Teacher Education (SLTE) has shown to have a great impact on undergraduates' beliefs regarding the way they will engage in different methodologies to teach EFL (Barahona, 2014a; Tagle et al., 2014). Henceforth, the importance of leaving room for EFL pre-service teachers to start reflecting upon the EFL curriculum seems crucial. It is deemed important to explore how guided instances of reflection could indeed help EFL pre-service teachers to put into practice what they are taught at university in SLTE programs. With this in mind, this article presents an action research study that explores the contribution that points of improvement as a reflective practice strategy may have in the pre-service teachers' planning of communicative-oriented lessons as part of their final practicum experience.

Theoretical Framework

Reflective practice. Echoing Dewey's words, one sees that reflection can be seen as an "active, persistent, and careful consideration of any belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the grounds that support it and the further conclusions to which it tends" (1933, p. 6). Henceforth, reflection is essential for an EFL teacher as, through it, teaching and classroom practices can be modified or reaffirmed by the identification of espoused theories or beliefs related to the exercise of their profession.

For EFL pre-service teachers, this becomes even more relevant since experiencing processes of reflection while they are starting to be immersed in school settings is seen as crucial in their learning-to-teach process (Barahona, 2014a). However, despite the importance of reflection instances, studies in the field of SLTE have shown that little time is devoted for pre-service teachers to engage in such processes, a practice which seems to be related mostly to academic and schools demands (Farrell, 2014). The Chilean context is not excluded from this reality as SLTE programs in this country still seem to be more oriented towards developing "linguistic competence and knowing about the language" (Martin, 2016, p. 37) rather than questioning or reflecting on practical matters. For example, some of the participants from Martin's study (2016), in which she investigated the curriculum of Chilean SLTE programs, reported that time was the main constraint when trying to implement lessons with a reflective focus.

For reflective practice to be carried out, there needs to be time for "language teachers [to] systematically examine their beliefs and practices about teaching and learning throughout their careers" (Farrell, 2013, p. 1). In this respect, EFL pre-service teachers in the Chilean context have been gradually introduced and immersed in these types of reflective instances in the past few years. This has been done by allowing EFL pre-service teachers to notice what their beliefs about teaching and learning and/or practices are, leading eventually to more informed pedagogical and classroom decisions, as well as to engage in different approaches to teaching (Díaz, Martínez, Roa, & Sanhueza, 2010).

In this respect, beliefs are a key element to becoming reflective practitioners; therefore, for the purposes of this study, providing an account of what is understood by beliefs in the educational context is relevant. Considering the various definitions which have been given to this construct (Borg, 2003; Kagan, 1992), beliefs will be understood here as "more or less integrated and consistent sets of ideas" (Solar & Díaz, 2009, p. 59) that impact the way teachers think, behave, and make decisions in the classroom, thus shaping their practices (Borg, 2003; Tagle-Ochoa et al., 2014). In addition, given that beliefs are ingrained in our memory, they will be seen as likely to be modified if processes of reflection take place (Farrell, 2013; Tagle et al., 2014).

With respect to the concept of reflection, for the purpose of this study, it will be conceived in terms of stages (Schön, 1983; Murphy, 2013; Farrell, 2013). These stages are said to be related to past, present and future teaching experiences. Each of those experiences helps EFL pre-service teachers to make sense of events that might have an impact on their pedagogical and classroom practices.

From Schön's perspective (1983, 1987), two main reflective processes are carried out when engaging in reflection: 1) when a pedagogical action is taking place and 2) after the action takes place. Those two processes of reflection are named reflection in-action and on-action respectively (Schön, 1983, 1987). Both processes are considered to be quite beneficial, particularly for pre-service teachers and nursing students (Murphy, 2013; Farrell, 2013). In order to complement the above reflective instances, Murphy (2013) and Farrell (2013) have added a third stage: reflection for-action. This phase adds the notion of future experiences by noticing the implications that the pedagogical action could have hereafter.

In view of the little space given to reflective instances in Chilean SLTE programs (Martin, 2016), the insights provided by Farrell (2000), Murphy (2013), and Schön (1983, 1987) have served as guidelines to design a reflective-based strategy, points of improvement, to equip EFL pre-service teachers from a Chilean university with awareness raising on the process of lesson planning.

Reflection on-action. Reflection on-action is related to what happens after a class has been implemented. Schön (1983) implied reflection on-action is the ability to analyze, review, and evaluate a situation in order to gain insights for future practice. According to Farrell (2013), this type of reflection allows teachers "to think critically about the lessons they taught, the learning objectives, the classroom activities and, thereby, building an awareness of the teaching process" (p. 3). For Conway (2001), this "looking back" implies "turning inward, examining one's own remembered experiences and/or anticipated experiences, not exclusively looking back in time" (p. 90). Thus, this process of reflection is related to how teachers are able to see themselves and their pedagogical decisions after they have taught.

Conway's insights (2001) on how reflection should take place help teachers to appreciate the importance of understanding the weaknesses and strengths of implemented lessons. The more these instances are provided to EFL pre-service teachers, the more they might improve 91 their awareness and willingness to modify their practices. Taking this into consideration, EFL pre-service teachers might be encouraged to look back on the lessons they have already performed in order to establish what went well, what did not, which factors might have influenced their pedagogical actions, and how those factors could eventually affect their future teaching practices and their own beliefs about language teaching and learning. EFL pre-service teachers are constantly collecting data that would allow them to plan actions (Farrell, 2012); the more they are encouraged to anticipate or prevent situations while they are planning, the more informed their decisions in the classroom might be as they have reconstructed knowledge from their own experience.

Reflection for-action. Once the aspects that need improvement have been identified in the stage described above, EFL teachers need to decide which actions will be taken and how those actions or changes would impact their future teaching practices. Thus, this reflection-for-action stage aids in improving upcoming classes since "it may entail a teacher's making note of the weaknesses in a lesson and proposing action to address these problems in future lessons" (Farrell, 2013, p. 4).

Wilson (2008) asserted that reflection for-action must be carried out in a systematic process. If this systematicity is neglected, "we are limiting the potential for the development of professionals" (Wilson, 2008, p. 183). Teacher education programs have neglected reflection for several years (Urzúa & Vásquez, 2008) and have left behind the ability to 'imagine' (Conway, 2001). Thus, pre-service teachers need to participate in instances of reflection in which they display the ability to imagine what could possibly happen in a certain situation. Urzúa and Vásquez (2008) suggest that this type of reflection might allow teachers to examine possible scenarios and anticipate events by taking action and considering their own teaching practices. Conway (2001) has added that, as pre-service teachers engage reflection for-action, they are able to deal with likely situations in a more positive perspective.

These instances would indeed "enable teachers to articulate to themselves what they do, how they do it, why they do it, and what the impact of one's teaching on students' learning is" (Farrell, 2012, p. 14). In order to achieve this, Wilson (2008) suggests aiding pre-service teachers in considering different scenarios and the strategies they need to apply to address those situations. Since EFL pre-service teachers participate from these processes, they engage in a dialogic reflection where they are able to hear their own voice by weighing competing claims and viewpoints, and exploring possible solutions (Hatton & Smith, 1995).

In sum, engaging EFL pre-service teachers in reflection on-action and for-action may lead to informed teaching decisions, and thus, a more suitable environment for learning.

Points of improvement as a dialogic strategy for reflective practice. Taken into consideration all the aforementioned characteristics of a systematic reflective procedure, points of improvement, as a dialogic strategy, is defined as an instance in which EFL pre-service teachers identify areas in which they feel weak, need to keep working, or need support. Through a guided dialogue, they are oriented in the process of reflection, which helps them gain awareness from previous lesson performance and determine the course of action to be taken. This dialogue will also guide them when considering the factors that might have affected their decisions, so that they are more likely to explore alternative solutions. This dialogic reflection considers "stepping back from, mulling over or tentatively exploring reasons" (Hatton & Smith, 1995, p. 42) as teachers become more aware of "the problematic nature of the professional action" (Hatton & Smith, 1995, p. 46). When EFL pre-service teachers engage in determining points of improvement, they have the opportunity to challenge their own beliefs about the process of teaching and learning. Hence, this reflective strategy aims at supporting them during their teaching practicum so that they are able to deal with those aspects that need more attention.

The Communicative Language Teaching approach. The Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) approach is widely used by language teachers over the world. It meant a shift away from the traditional approaches to English language teaching which focused on mechanical repetition and decontextualized tasks. Despite its popularity, this approach is often "misunderstood and misapplied" (Scrivener, 2011, p. 31). This misunderstanding can be related to the idea of emphasizing only speaking and listening skills in the classroom, not being explicit on learners' errors, and also on excluding grammar from the curriculum (Wu, 2008). It can be argued then that EFL teachers might not be familiarized with what the application of CLT in the classroom really implies, and thus, their own beliefs regarding the main characteristics of this approach might have an impact on how they teach English.

The main focus of CLT is to promote the development of learners' communicative competence. According to Richards (2005), in order to be engaged in a more communicative-oriented methodology, language teachers should focus language learning on real communication, providing learners with opportunities to try out what they know, to be tolerant of learners' errors, and to understand them as examples of progress in communicative competence. In addition, opportunities for learners to develop both accuracy and fluency should be provided by integrating skills such as speaking, reading, and listening, and by allowing students to unveil language structures. Hence, in order to carry out a communicative language class, a lesson plan with these characteristics and clear awareness of the local teaching context must be designed. In the Chilean context, providing learning experiences that are context dependent, and close to students' lives and interests, is highly relevant. Given the inequality gap (Agencia de Calidad, 2019), there are many contexts in which English is perceived as irrelevant, and associated with well-off groups (British Council, 2015). Thus, English language lessons are expected to have a communicative purpose that allows learners to connect and engage with the language experience.

Lesson planning. Planning is helpful when EFL pre- and in-service teachers need to decide what they are going to teach based on their school demands and context. Therefore, lesson planning should be considered as a "proposal for action" (Harmer, 2015, p. 211) which serves as guidance and not as a fixed set of procedures that must be carried out by language teachers. In this respect, Richards and Renandya (2002) define lesson planning as "a process of transformation during which the teacher creates ideas for a lesson based on understanding of learners' needs, problems, and interests, and on the content of the lesson itself" (p. 27). In addition to this, Scrivener (2011) characterizes lesson planning as a "thinking skill" since it serves to foresee what will happen in the classroom (its atmosphere, learners, and materials).

In the EFL context, lesson planning should address learners' needs, problems, and interests (Richards & Renandya, 2002), and consider external elements which may affect the enactment of the plan, namely space, students, time, and materials (Diaz Maggioli & Painter-Farrell, 2016). Similarly, lesson planning should address the integration of the four language skills, contextualized and authentic tasks, and meaningful patterns of interaction among learners, all of this in order to promote communication (Ministerio de Educación de Chile, 2015). However, this task turns out to be challenging for EFL pre-service teachers when they realize their students' level of English, the resources and space available, and the administrative challenges that they have to face in their daily teaching. Henceforth, knowing how to design and implement a lesson that results appropriate for their teaching context is crucial for these teachers.

During EFL pre-service teachers' education, compulsory subjects in the curriculum include those related to methodologies and approaches to teach English. Martin (2016)) carried out a study related to SLTE in Chile, in which she found that SLTE programs included modules related to the history of traditional methods, lesson planning, and strategies for developing the four language skills. In addition, she unveiled that while only 31% of these universities had instances of reflection present in their programs, most of them had one or two EFL methodology courses with four hours weekly on average. This situation means that the fundamental instances when pre-service teachers in these programs could integrate their teaching knowledge and reflect on their teaching beliefs may not be enough. This insight could bring implications to their future as teachers of English.

In the program in which this current study took place, the reality did not seem much distant from the one reported by Martin (2016). Fortunately, curricular changes were carried out in 2016 and a new plan was designed. This new plan provides teacher educators with the opportunity to include instances of reflection such as reflective practice as a core topic in all pedagogical modules, starting from first year.

Another difficulty EFL pre-service teachers seem to face when planning a lesson is related to various elements such as learners' needs, teaching context, curriculum demands, and ministerial recommendations. Despite these teachers' theoretical knowledge on approaches to language teaching, EFL pre-service teachers seem more concerned with preventing or solving situations in the classroom rather than paying attention to the instruction delivery (Barahona, 2014b; Díaz & Ortiz, 2017). In this regard, SLTE in general, and in Chile in particular, should embrace this tension during pre-service teachers' education so that they could feel more open in being flexible in the delivery, as well as being context aware to design lessons in a more effective way.

Second language teacher education in Chile. SLTE programs in Chile are undergraduate courses which last five years in most universities. Generally, in their last year, pre-service teachers in these programs are expected to undertake the final teaching practicum, in which they have to carry out different tasks required by both the program and the school where they do their practicum. However, tension arises between university programs and schools as both institutions tend to focus on theory and practice respectively (Barahona, 2014a). In this scenario, planning an English language lesson can become a challenging task as school realities can strike pre-service teachers really strong (Sahintaskin, 2017). What EFL teachers find in their context helps them reconceptualize how planning should be and how it should be addressed. This is why reflection is seen as a useful tool to change or reshape pre-service teachers' planning ideas (Barahona, 2014a; Díaz & Ortiz, 2017; Farrell, 2001; Tagle-Ochoa et al., 2014).

Method

This study is framed within an action research design. It studies a particular educational setting to improve its learning and teaching processes. Therefore, its design involves the following overlapping stages: planning, action, observation, and reflection (Burns, 2009).

Research problem. As part of the planning stage, the problem which was identified was based on my personal experience as a teacher educator. EFL pre-service teachers struggle when they are required to plan lessons within the CLT. This has been noticed, particularly, within the module Professional teachingpracticum at a Chilean university where this study was conducted. The group of pre-service teachers, who participated in the study, faced problems when they had to plan communicative-oriented lessons since they did not fully understand how to apply CLT in their own teaching context. Even though they were able to establish points of improvement regarding this challenge, these points were neither present in their following lesson plans nor reflected in the implementation of their lessons. It seemed at that point that the main issue was their lack of reflection on their pedagogical decisions. This was evident during the process of lesson planning, since they were not able to consider sequence of activities, meaningful tasks and topics, students' preferences, interests and characteristics, and macro-skills.

During the weekly sessions, this group of pre-service teachers reported that they wanted to work on their lesson plans in order to make them communicative-oriented. With this in mind, the research question guiding this study is: how does the use of points of improvement, as a strategy for reflective practice, support EFL pre-service teachers' skills to plan communicative-oriented lessons?

Research objectives. The objectives of the study are (1) to explore the contribution of using points of improvement, as a reflective strategy, on the participating EFL pre-service teachers' ability to plan communicative-oriented lessons; and (2) to identify the participating EFL pre-service teachers' beliefs about communicative-oriented lessons and their perceptions regarding the contribution of using points of improvement, as a reflective strategy, on their ability to plan communicative-oriented lessons.

Participants. There were eleven EFL pre-service teachers participating in this study, eight females and three males aged from 23 to 25 years old. Their participation was based on their full attendance to the course called Professional Teaching Practicum Workshop provided as part of a teacher education program by a Chilean university. The criteria for selecting this sample considered the following aspects:

Previous courses of ELT methodology: all the participants have taken courses of ELT methodology.

Lesson planning courses: the participants have been part of courses in which they had to plan English language lessons.

Previous practicum experiences at schools: all participants have already been immersed in school contexts. Participating pre-service teachers had previous experiences of teaching English at least two hours weekly at school.

The aforementioned criteria allowed the participants to rely on their previous teaching knowledge and experiences to reflect on their current practices.

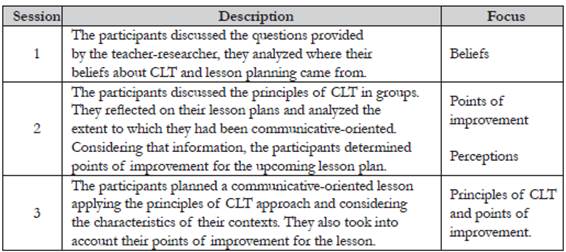

Research procedures. In the intervention (action stage), a planning phase was first carried out within a four-week period of time in which the teacher-researcher in charge of the Professional Teaching Practicum Workshop observed the participants' lesson delivery and provided feedback on the design of their lesson plans. Based on this first phase, the need for reflecting on the participating teachers' decisions appeared. Points of improvement emerged then as a plausible strategy to guide the participating EFL pre-service teachers as a first attempt for reflective practice. Eventually, the intervention stage was carried out focusing exclusively on encouraging and developing processes of reflection upon the procedure followed for designing the participating teachers' lesson plans. This stage lasted for a month, with a frequency of one session (90 minutes each) per week.

Data collection instruments

Questionnaire (see Appendix A). This instrument sought to collect information regarding the participants' beliefs about the process of lesson planning and communicative-oriented lessons. It consisted of a set of open-ended questions with two dimensions: process of lesson planning and CLT.

Focus group (see Appendix B). The focus group was conducted after the implementation of the reflection instances in order to explore the extent to which the use of points of Stages of the action plan. The action plan had three stages as described below: improvement contributed to enhance the teachers' lesson plans. This instrument was chosen based on its usefulness to unveil factors that may influence motivation, perceptions, or opinions about a topic; in this case, the contribution of the reflective strategy in their ability to plan communicative-oriented lessons (Silverman, 2013).

Data analysis techniques. Thematic analysis was used to analyze the data collected from the questionnaire and focus group. By following Braun and Clark (2006), the analytical stages considered: Familiarization with the data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing, defining and naming the themes.

Findings

Findings will be reported in line with the research objectives by showing the most recurrent categories and codes yielded from the participants' responses. Each code within a category will be described and illustrated with excerpts.

Pre-service teachers' beliefs about communicative-oriented lessons. The most repeated categories related to pre-service teachers' beliefs about communicative-oriented lessons are related to the contextualization of the contents to be taught and the skills which should be fostered in the different activities done in class. The group of participants considers contextualization relevant as they expressed that giving a context or situation for the class activity would allow their students to understand the purpose of using English. The following excerpts illustrate the participants' most recurrent opinions:

"Contextualization of the content: this is highly important since students need to know when and how to use what they learn." (PST2, Questionnaire)

"Students need a situation in which they can use the language effectively and in a realistic way." (PST3, Questionnaire)

These responses show that the participating EFL pre-service teachers are more likely to engage in communicative-oriented lessons as, for them, contextualization of the contents presented seems crucial. By doing so, they would help their students to acquire the language in a meaningful way as they are able to access English in real-life situations.

Participating EFL pre-service teachers also consider linguistic skills as important when delivering their lessons because these might promote students' involvement in the lesson, with particular attention to productive skills. The following excerpts show this point.

"Emphasis on productive skills (speaking-writing)." (PST6, Questionnaire)

"Focus on skills rather than structure because the communicative approach proposes teaching by motivating students to learn through developing or actually using skills instead of focusing on structures." (PST2, Questionnaire)

These perceptions suggest that the participants understand the manner in which they need to orient their lessons, always by following communicative aspects such as contextualization of language content and using the language through actual (written or oral) communication. However, these are only two aspects of communicative-oriented lessons. The participants did not mention aspects related to interaction among learners or diverse assessment instances, amid the various characteristics of a communicative-focused class (Richards, 2005).

Thus, it seems that what these teachers have so far experienced in their language teaching methodology courses might have had an effect on their beliefs regarding what is most important to include in communicative-oriented lessons. At this pre-service stage, they seem to be aware of some of the main aspects of CLT to be developed in their classes, so it is expected that such knowledge is extended during their preparation stage while immersed in the various courses related to teaching methodological issues (Martín, 2016).

Pre-service teachers' perceptions about the contribution of points of improvement for their ability to plan communicative-oriented lessons. Regarding points of improvement, the participants mostly mentioned the benefits that this strategy provided them. One of the first benefits mentioned had to do with how this activity helped them raise their awareness of their teaching decisions and what needs further development. These pre-service teachers mentioned the positive impact of reflecting before and after they designed their lesson plan as a way of monitoring their own teaching decisions. This aspect can be observed in the following excerpt:

"It has helped me a lot to establish improvement points, and it's the first thing I do after class. I am more aware in classes." (PST1, Focus Group)

"I have become more aware of my pros and cons as a teacher while establishing points of improvement. When you are conscious about them, you know that you can change that situation. During the feedback session I could reaffirm and realize what was effective or not. I can make more informed decision while I am teaching. If you are committed to what you do, you constantly think about how to improve and that becomes your routine as a teacher." (PST, Focus Group)

For this group of teachers, establishing points of improvement seemed useful and easy to do as part of their teaching practice since they focused on a particular aspect of their lessons as a starting point, this in turn allowed them to observe their practice mindfully. The participants reported that, after the intervention, they felt more aware of their teaching decisions while giving the lesson. This could be an example of reflective practice, as it allows teachers to think back about their lessons and how to improve them (Farrell, 2013). This is an interesting finding since awareness of how their teaching occurs is more likely to happen when they have been exposed to these reflective tasks for a longer period of time. Thus, this insight seems to suggest that EFL pre-service teachers' involvement when they determine points of improvement in their lesson plans has positively influenced their beliefs since the gap between their disciplinary and pedagogical knowledge started to narrow down.

In this respect, Contreras and Prieto (2008) assert that beliefs represent a relevant basis for pre-service teachers during their teaching practicum, because beliefs guide their teaching. That is to say, if beliefs are not challenged, they would remain, and changes will not take place. The fact that they reflect on their teaching actions is the first step to start modifying their pedagogical practices, since this reflective practice strategy guided them on entering into "a dialogue with themselves and other teachers so that they can reach a new level of awareness and understanding of their practice" (Farrell, 2015, p. 35).

In fact, the participating EFL pre-service teachers described points of improvement as a strategy that they could incorporate in most of their lessons as shown below:

"I always think of my points of improvement, but I consider them for all the lessons, not only for the ones being observed at university." (PST10, Focus Group)

"Immediately after I establish these improvement points, I go and investigate how I can improve that. I'm looking for strategies on the internet and I'm asking 'how can I implement it?' and I start testing it in class." (PST7, Focus Group)

How these pre-service teachers used this strategy for reflection aimed at overcoming challenges in a creative way is evident in the previous excerpts. These also illustrate that the pre-service teachers take an agent role in their teaching decisions showing willingness to find solutions and improve their practice. It could be argued that they are becoming reflective practitioners, as they are able to notice improvements in their own lessons.

Another benefit resulting from the use of points of improvement was considering new elements in their planning. The lesson plans included more communicative-oriented activities, educational contexts played a huge role in their lesson, and English became a means to give more importance to students' cultural backgrounds and preferences. The fact that after the intervention they started using engaging topics related to their students' interests shows that they are more concerned about their own teaching contexts and the tasks they prepared. This point can be observed in the following excerpts:

"There is an element that I take into account: whatever it is, it should be communicative and simple, so that the students can quickly understand the idea of what to communicate and feel safe." (PST1, Focus Group)

"I consider that I do have to create a story to present the context of the task. I use let's imagine that, because in that way they feel they have a purpose to communicate and not just answering questions to the teacher." (PST2, Focus Group)

"It's to take into consideration the students' preferences: what motivates them, where they move, what the focus of their communication is. The learning objective of the class should be according to how students live, their experiences; we teachers adapt the class to them, not them to the class." (PST7, Focus Group)

As can be seen, through the use of points of improvement, the participants were able to consider elements of CLT, their students' experiences, and the inclusion of a communicative purpose and context as fundamental for their lesson planning. By doing so, this group of EFL pre-service teachers show that this approach was suitable to help their students learn English despite their usual struggle to apply CLT in the classroom (contextual factors, such as class size and institutional requirements).

Thus, this point shows that SLTE programs should consider opportunities for EFL pre-service teachers to adapt CLT to their own reality. Factors such as large classes and low performance in the English language subjects could hinder the process of lesson planning. However, that could be changed if EFL pre-service teachers develop more awareness -through reflective instances such as the one studied here - about their context and how to take advantage of the socio-cultural background of their students.

Conclusions

This study aimed at exploring the contribution that points of improvement, as a reflective practice strategy, may have in pre-service teachers' planning of communicative-oriented lessons as part of their final practicum experience. The participants' perceptions in this respect showed that their beliefs regarding communicative-oriented lessons are more related to the contextualization of the language content and on a focus on producing the language.

Similar aspects were also highlighted in relation to the potential benefits of using points of improvement - as a strategy for reflective practice - when planning their lessons with a communicative focus. These EFL pre-service teachers became more aware of these aspects which they perceived as fundamental of CLT, but which they had to adapt to their own teaching contexts. This latter realization, that of the need for adapting their lesson plans, was one of the main results of the reflective strategy studied here. By using points of improvement these pre-service teachers became more aware of their own teaching decisions and what needed further development and improvement. This reflective instance also encouraged their agency to look for solutions to overcome the challenges faced (e.g. adapting CLT to their own contexts), thus to improve their teaching practice. Hence, the benefits of using such reflective instance served these participants to "gain some reflective distance to understand better the meaning of lived experience" (Conway, 2001, p. 90), in this case, of their initial experiences at planning lessons with a communicative focus.

Despite the small scale of this study, the benefit of providing a systematic reflective instance to those who are soon to become teachers is quite evident. Reflection needs a high status as part of teacher education, particularly in SLTE, in order to promote major changes in the Chilean EFL classroom.

Changes cannot be made if pre-service teachers are not immersed in instances where they can share their experiences and challenge their own beliefs in a supported environment. The findings of the current study suggest that, by being given the opportunity and guidance, EFL pre-service teachers could embrace reflection as part of their teaching practice. Slight changes in courses in EFL teaching methodology, close to the local context, can actually open the door to a reflective teacher who embraces the richness of the Chilean classroom.

Further research

As this study mainly focused on reflection on and for action, it would be interesting to see how EFL pre-service teachers are able to consider their points of improvement when they have to implement their lesson plan in the classroom. It would also be interesting to study the implementation of this strategy for reflection all along the practicum line within a teacher education program. This would serve to confirm the benefits reported here and to extend evidence of its potential usefulness.

Limitations and Implications

This action research study was carried out as part of the weekly sessions that a group of EFL pre-service teachers had at a university as part of their undergraduate SLTE program for a limited period of time; therefore, there were no opportunities to observe their spontaneous decisions while they were teaching and how those decisions may have influenced the way they conceived the process of lesson planning.

Participants declared feeling unprepared to design communicative-oriented lessons. The main implication for the teacher-researcher in her/his practice as teacher educator is that more instances to apply and reflect on their knowledge about CLT and the Chilean teaching contexts must be included in the syllabus in order to guide the participating pre-service teachers in bridging the gap between theory and practice. Similarly, the first sessions of the Professional Teaching Practicum Workshop should be devoted to talking about this approach and unveiling the pre-service teachers' beliefs about it in an attempt to help them shape their teaching skills. This opportunity is relevant for these pre-service teachers to discover whether they are actually applying the principles of a communicative-oriented lesson that is appropriate for their local context.

Another important implication is for the teacher-researcher as a teacher educator: more room should be given to reflection. It was clear that despite the few sessions devoted to the intervention of points of improvement, the EFL pre-service teachers benefited considerably. They expressed the opportunity they had to think about their past, present and future teaching actions systematically, which allowed them to identify what needed to be improved and modified. The major benefit of such reflection helped this particular group of teachers to reconceptualize their communicative-oriented lessons by considering their specific teaching contexts, thus adapting the theoretical understandings of the concept not only to the physical context of the class, but also to the particular needs of their students. Hence, formal reflective instances such as the one here proposed may indeed be aiding in narrowing the gap between theory and practice.