Introduction

Language assessment is a purposeful and impactful activity. In general, assessment responds to either institutional or social purposes; for example, in a language classroom, teachers use language assessment to gauge how much students learned during a course (i.e. achievement as an institutional purpose). Socially, large-scale language assessment is used to make decisions about people's language ability and decisions that impact their lives, e.g. being accepted at a university where English is spoken. Thus, language assessment is not an abstract process but needs some purpose and context to function. To meet different purposes, language assessments are used to elicit information about people's communicative language ability so that accurate and valid interpretations are made based on scores (Bachman, 1990). All assessments should have a high quality, which underscores the need for sound design (Alderson, Clapham, & Wall, 1995; Fulcher, 2010).

In the field of language education in general, language teachers are expected to be skillful in designing high quality assessments for the language skills they assess (Clapham, 2000; Fulcher, 2012; Giraldo, 2018; Inbar-Lourie, 2013). The design task is especially central in this field; if it is poor, information gathered from language assessments may disorient language teaching and learning.

In language assessment, scholars such as Alderson, Clapham, and Wall (1995), Brown (2011), Carr (2011), and Hughes (2002) have provided comprehensive information for the task of designing language assessments. Design considerations include clearly defined constructs (skills to be assessed), a rigorous design phase, piloting, and decisions about students' language ability. Within these considerations, it is notable that the creation of language assessments should not be taken carelessly because it requires attention to a considerable number of theoretical and technical details. Unfortunately, scholars generally present the design task in isolation (i.e. design of an assessment devoid of context) and do not consider -or allude to- the institutional milieu for assessment.

Consequently, the purpose of this paper is to contribute to the reflection in the field of language education on how the task of designing language assessments needs deeper theoretical and technical considerations in order to respond to institutional demands in context; if the opposite (i.e. poor design) happens, language assessments may bring about malpractice and negative consequences in language teaching and learning. The reflection intended in this article is for classroom-based assessment. Thus, I, as a language teacher, consider the readers as colleagues who may examine critically the ideas in this manuscript. The information and discussion in this paper may also be relevant to those engaged in cultivating teachers' Language Assessment Literacy (LAL), e.g. teacher educators.

I construct the reflection in the following parts. First, I overview fundamental theoretical considerations for language assessments and place emphasis on the specifics of the technical dimension i.e. constructing an assessment. Second, I stress the institutional forces that can shape language assessments. Finally, these components (theory, technicalities, and context) form the foundations for assessment analysis in the last part of the paper, in which I intend to show how the relatively poor design of an assessment may violate theoretical, technical, and institutional qualities, leading it to invalid decisions about students' language ability.

Qualities of Language Assessments

In this section, I present six fundamental qualities for language assessments. Knowing about them, although in general terms, helps to understand the assessment analysis in the last section of the paper. I draw on the work by Bachman and Palmer (2010) to represent a widely-accepted framework for language assessment usefulness. Since most qualities below have sparked considerable discussions in the field of language assessment, for comprehensive coverage of the research and conceptual minutiae, readers might resort to Fulcher and Davidson (2012) or Kunnan (2013).

Construct validity. This is perhaps the most crucial quality of language assessments. If an assessment is not valid, it is basically useless (Fulcher, 2010). Before 1989, validity was considered as the capacity of an instrument to assess what it was supposed to assess and nothing else (Brown & Abeywickrama, 2010; Lado, 1961). After 1989, Messick's (1989) view of validity replaced this old perspective and is now highly embraced: The interpretations that are made of scores in assessment should be clear and substantially justified; if this is the case, then there is relative present validity in score interpretations. For interpretations to be valid, naturally, assessments need to activate students' language ability as the main construct (Bachman & Palmer, 2010).

Reliability. Strictly in measurement terms, reliability is calculated statistically. A reliable assessment measures language skills consistently and yields clear results in scores (or interpretations) that accurately describe students' language abilities. The level of consistency is suggested when the assessment has been used two times under similar circumstances with the same students. However, as Hughes (2002) explains, it is not practical for teachers to implement an assessment twice. For illustration, suppose two teachers are checking students' final essays, so every essay receives two scores. If the scores are widely different, then there is little or no consistency in scoring, i.e. the scores are unreliable. If scores are unreliable, this will negatively impact the validity of interpretations: The two teachers are interpreting and/ or assessing written productions differently.

Authenticity. Authenticity refers to the degree of correspondence between an assessment (its items, texts, and tasks) and the way language is used in real-life scenarios and purposes; these scenarios are also called TLU (Target Language Use) domains (Bachman & Palmer, 2010). Assessments should help language teachers to evaluate how students can use the language in non-testing situations, which is why authenticity is a central quality of language assessments (Bachman & Palmer, 2010).

Interactiveness. Language assessments should help students activate their language skills (i.e. the constructs of interest) and strategies for dealing with the assessment itself. If an assessment only stimulates a student's knowledge of math (or any other subject) then this assessment scores low on interactiveness. Likewise, the assessment should activate the relevant topical knowledge to perform, for example, in a speaking or writing task.

Practicality. Suitable and available human and material resources should contribute to the design, administration, and scoring procedure for a language assessment. If resources are scarce, assessment practicality decreases. Since human, physical, and time resources are needed (Bachman & Palmer, 2010), they should be used in a way that helps to streamline the assessment development process, ergo making it practical. Using a long writing assessment in a 40-student group may not be practical for scoring, as it will take too much time for one teacher to assess and interpret students' constructs; this can be especially impractical if the teacher needs to balance other teaching responsibilities, namely planning future lessons.

Washback. It is generally considered as the impact that assessments have on teaching and learning. It can be positive or negative (Alderson & Wall, 1993). Washback has been discussed as part of impact, or the influence of assessments on people and society. After Messick (1989), the field has conceptualized impact as consequential validity. Taken together, the overall consensus seems to be that language assessments should lead to beneficial consequences for the stakeholders involved (Bachman & Damböck, 2018; Shohamy, 2001). In language classrooms, results of language assessments should help improve students' language ability. Shohamy (2001) remarks one should not use them as elements of power, e.g. to discipline students for their misbehavior in class.

Ethics and fairness. Even though these two principles are not part of the framework in Bachman and Palmer (2010) or of technical discussions for assessment design, they have had much heated debate in language assessment. As such, ethics and fairness are not qualities of assessment (reliability and authenticity are) but philosophical pillars that drive professional practice. Thus, ethics refers to professional conduct to protect the assessment process from malpractice; this conduct involves stakeholders in assessment, namely test-takers and professional testers (International Language Testing Association, 2000) but arguably includes language teachers and students (Arias, Maturana, & Restrepo, 2012). Fairness, on the other hand, refers to the idea that all students should have the same opportunity to show their language skills. No student should have an advantage over others (ILTA, 2000); similarly, irrelevant variables (e.g. a student's race) should not be used to assess students differently, for better or for worse. Thus, an unfair use of an assessment can be unethical.

In terms of the qualities of construct validity, reliability, authenticity, interactiveness, practicality, and washback, Bachman and Palmer (2010) and others (for example, Fulcher, 2010) argue that they are relative rather than absolute. An assessment is relatively practical rather that completely practical or totally impractical. The qualities are evaluated by, first of all, having an assessment's purpose in mind. Additionally, as commented earlier, these qualities have received considerable attention and led to differing views on their state of affairs. When it comes to design, however, guidelines for constructing assessments are agreed; this is the next topic I review in this paper.

Technical Considerations for Designing Language Assessments

These considerations refer to the nuts and bolts for writing useful items, tasks, and rubrics to be used in language assessments. As explained earlier, when authors refer to design technicalities, the focus is usually on assessments themselves rather than the theoretical and institutional universe to which the assessments respond.

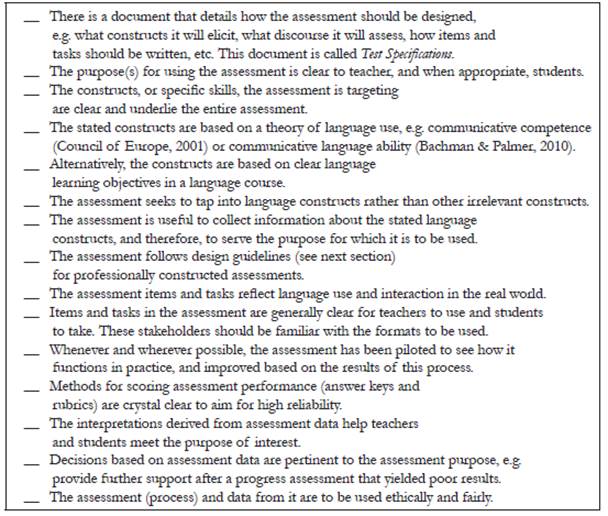

In language assessment textbooks specifically designed for language teachers, authors walk readers through the genesis, qualities, development, and evaluation of assessments in general (for example, McNamara, 2000). Conversely, authors dedicate extensive sections of their books to explaining the intricacies of writing assessments. Table 1 below synthesizes the considerations that generally apply to all assessments, as seen in Alderson, Clapham, and Wall (1995), Buck (2001), Hughes (2002); Brown and Abeywickrama (2010), Brown (2011), and Carr (2011). The table is presented as a checklist for those interested in using it for classroom-based language assessment.

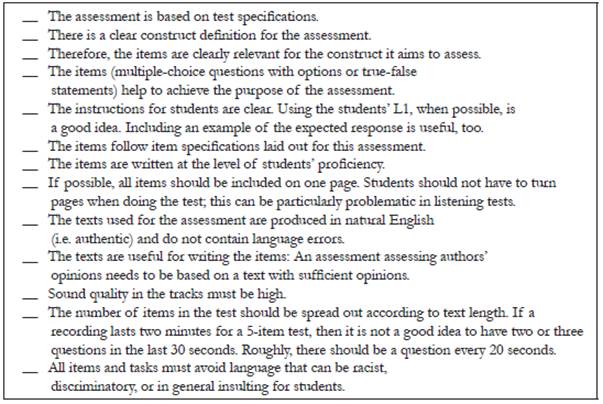

The considerations in Table 1 represent sound practice in assessment for language teaching and learning. They imply professionalization of the field and, when implemented properly, they reflect high levels of LAL, as scholars have discussed (Fulcher, 2012; Taylor, 2013; Malone, 2017). At a granular level, Brown (2011) and Carr (2011), for example, have provided specifics for constructing assessments. Tables 2 and 3 below contain a synthesis of guidelines for constructing listening assessments. I must state that I chose this skill arbitrarily as it is the construct underlying the sample assessment in the last part of the paper, Analysis of a Language Assessment. The listening assessment I examine is meant as an example of how a poorly designed assessment can be problematic. Tables 2 and 3 below gather ideas from the authors in Table 1 (except for Fulcher, 2010, whose ideas I included in these new tables). I present the tables as checklists for teachers to design or evaluate their assessments. In Table 2, readers can find crucial generalities for designing listening assessments. Notice that most of these guidelines can also apply to the design of reading assessments.

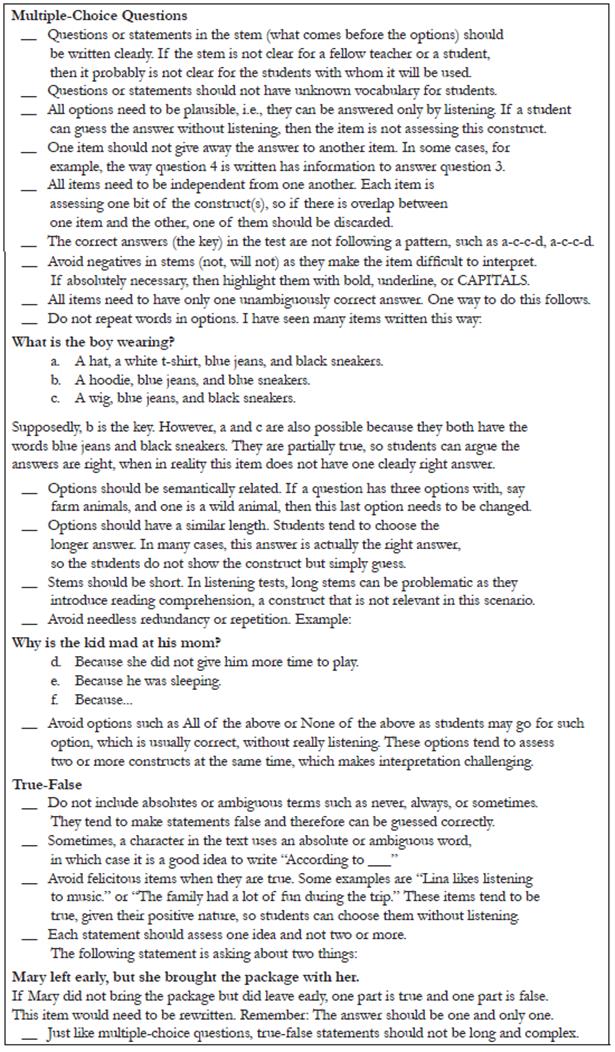

Table 3 explains the specifics for creating sound multiple-choice and true-false items to elicit listening skills specifically. However, as is the case with Table 2, applicable guidelines below can be used for designing reading assessments.

Tables 1, 2, and 3 synthesize the most important technicalities for listening assessments as they bring together ideas that conform to conscientious design. Additionally, they can help language teachers to critically evaluate and reflect upon how they design language assessments. Although the above guidelines are used to analyze a sample listening assessment in this paper, broad connections can be drawn to the other language skills, namely reading, speaking, and writing. Such relationships include the following:

Language assessments serve purposes, so they must be clear for all parties involved; examples are diagnostic, progress, and achievement assessments.

Any language assessment needs to have a clear description of the constructs (specific skills) to be assessed.

Language assessments should be based on test specifications; this is a document that explains what the instrument measures and what its purpose is; how items (for listening and reading) and tasks (for speaking and writing) can be constructed, including the number of sections, for example, among other considerations.

The method used (i.e. the assessment itself) should elicit the construct in the test specifications and be useful to achieve the stated purpose.

For further evaluation and reflection, language teachers may consider their assessment life-worlds (Scarino, 2013), i.e. the institutions where they do assessment. I discuss this matter in the next paragraphs.

Institutional Considerations for Designing Language Assessments

The previous section displays the key issues to design or evaluate language assessments as a task that requires detailed attention. Now I refer to what may be uncharted territory in the design of language assessments. Specifically, I discuss the institutional policies that can shape language assessments, particularly in the Colombian context. The overall message is that contextual and institutional considerations should be well-thought-out for designing useful assessments.

In Colombia, Decreto 1290 by the Ministry of National Education (2009) enacts the concepts, characteristics, procedures, and policies that guide assessment at educational institutions. Colombian elementary and high schools should implement this decree. Consequently, the decree is written for all school teachers in Colombia and also, naturally, it applies to language teachers, so it may be construed as a powerful force that has the potential to influence language assessment. For example, the decree establishes the use of self-assessment instruments, a practice that is highly encouraged in language assessment (Oscarson, 2013). This means that alternative assessment, in which students are responsible for their own learning, is suggested in the decree and the field of language assessment.

Additionally, the decree alludes to ethical uses of assessment, so it is exclusively concerned with documenting and improving student learning. That is to say, assessment should be used to see how much students are learning about a subject, whether it is biology or French; it should not be used to scare students or control them.

National standardized examinations in Colombia (such as Pruebas Saber 111) represent another influential national and institutional policy that impacts language assessment. Language teachers in Colombia may replicate test items and tasks from this examination so that they prepare students to take it, although this is not necessarily a successful practice (Barletta & May, 2006). This same situation is evident in other contexts where language teachers' assessments reflect the constructs of national tests (for example, see Sultana, 2019).

Additionally, specific details about how assessment should be done are described in the PEI (Proyecto Educativo Institucional - Institutional Educational Project) and the Manual de Convivencia (roughly translated as Manual for Coexistence) of each Colombian school. Both documents have origin in the Colombian general law of education No. 115. Because these two documents regulate schools as a whole, they can as well influence language teachers' work. Although the documents are indeed necessary in schools, oftentimes their prescriptions conflict with language teachers' perceptions, a situation which can lead to tensions in language assessment (Barletta & May, 2006; Hill, 2017; Inbar-Lourie, 2012; Scarino, 2013).

More specifically, assessments may be influenced by the language learning philosophy of each school. If a school considers communicative competence as the main goal for language education, and this is clearly stated in the school curriculum, then assessments should likewise elicit communicative competences. However, as studies in Colombia and elsewhere have shown (Arias & Maturana, 2005; Cheng, Rogers, & Hu, 2004; Díaz, Alarcón, & Ortiz, 2012; Frodden, Restrepo, & Maturana, 2004; López & Bernal, 2009), there tends to be a discrepancy between beliefs and practices: Language teachers believe communicative language assessment is important but frequently their practices show emphasis on linguistic constructs through traditional assessments.

In a related manner, the language curriculum, and specifically syllabi, built from each school's PEI can directly influence language assessment.2 Scholars in language assessment (for example, Bachman & Damböck, 2018; Brown & Hudson, 2002) argue that instruments have content validity provided that they elicit the specific language skills and knowledge that are part of a course or syllabus. Hence, syllabi serve as a point of reference to develop assessments and interpret the data that emerge from them.

Another aspect that influences language assessments is each school's modality. For example, in Colombian schools, in tenth and eleventh grades, students usually receive additional instruction in a particular subject, e.g. commerce, mechanics, interculturality, and tourism, among others. Given these modalities, language assessments may revolve around these general topics to document and drive language learning. Even though I have not seen any published studies describing this practice in Colombia, my personal interaction with high school teachers has confirmed that they connect language assessments to the school's modality, hoping to make this assessment more relevant and authentic for students.

Last but not least, language teachers consider students for designing language assessments. Learner characteristics that may shape assessment include their proficiency level, learning styles, age, needs, and even interests. Since classroom language assessment is mainly concerned with improving language learning (Bachman & Damböck, 2018; Fulcher, 2010), it becomes paramount then to devise high-quality language assessments for students as stakeholders who are directly impacted by them.

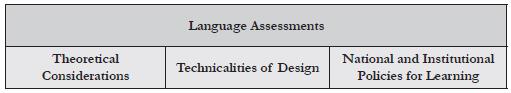

To summarize, language assessments can be influenced by three major components: theoretical ideas that apply to language assessments, technical issues that represent professional design, and contextual and institutional policies in which language assessment occurs. Figure 1 depicts the relationship between language assessments and the forces that can shape and support them.

Taken together, the aforementioned force a position of language assessment as a central endeavor for teachers and students. Given the importance that the process of doing assessment represents, the design of assessments is one of its pillars.

Analysis of a Sample Language Assessment

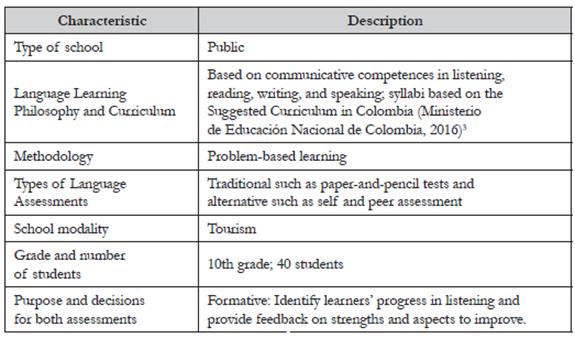

The purpose of the analysis presented in this section is to have readers, especially language teachers, reflect on the design of a listening assessment in light of the discussion held in the preceding sections. For context, Table 4 includes information of an example scenario for this sample listening assessment.

The listening assessment is targeting this construct: Identify specific information on how ecotourism projects have impacted the areas where they operate and the people who live in and visit them. There are ten items -five multiple-choice and five true-false-meant to elicit this construct. Further, the assessment was to be applied in the middle of a language course, hence the purpose of checking progress.

I recommend that readers copy and paste or print out the Appendix (i.e. the assessment) so that they can reflect on it as they read the analysis that follows. The analysis starts with theoretical aspects, then uses technical considerations, and finalizes with institutional policies.

Theoretical level. The listening assessment is about collecting information on how students identify specific information on the impact of ecotourism projects. Items 1 (organizations speakers talk about), 3 (location of Los Flamencos), 9 (changes in the sanctuary), and 10 (Henry's team) are about collecting information on other specific information, not the one expected in the construct. One way to circumvent the problem of assessing irrelevant constructs is to rewrite the construct specification for this assessment. Additionally, items 2 (what Nativos Activos do) and 3 (location of Los Flamencos) have more than one possible answer: Options a and cin item 2 overlap, which also happens with options c and d in item 3. This has an effect on the reliability of this assessment because the right answer is not consistent. In other words, the correct answer should be only one, and not two as it happens with these two items. Option c in question 4 (why Minra loves working with Nativos Activos) is the longest answer and it happens to be the key (i.e. the correct answer). This means a student can guess and get the item right for the wrong reasons (i.e. without actually listening); students tend to choose the longest answer when everything else fails (Brown, 2011; Carr, 2011). Guessing can also happen with item 10 (Henry's team), which seems obviously false in the context expressed in the recording.

Multiple-choice and true-false items lack authenticity as these are not operations we do in real life: We do not listen to natural conversations with options from which to choose. However, the topic in the recording (touristic places in Colombia) and the places talked about are real; also, in real life, students may be interested in listening to someone explaining the impact of ecotourism projects, especially at a school with the modality explained in Table 4.

This assessment is relatively interactive as it engages listening skills and test-taking strategies (e.g. guessing); the latter can obscure interpretations about the target construct. If students knew about the places being discussed in the recording, then the assessment would be eliciting world knowledge rather than listening skills. On the other hand, items 5 (benefit Minra does not mention) and 6 (structural improvements) seem to be directly engaging the operations necessary for students to show the construct. As for practicality, the item types in this assessment can be scored easily, but their design requires a high level of detail and expertise, as Tables 2 and 3 suggest.

The washback effect of this assessment may have been limited, since students got a score but did not receive information on what exactly to improve. This is particularly problematic as this assessment was meant to provide feedback on progress; in short, it was more summative than formative, as initially considered in Table 4.

Finally, since this assessment has poorly designed items, there may be wrong conclusions about students. Some may have gotten items wrong because of design, so the scores do not lead to clear interpretations. This then causes a problem of fairness because the score does not accurately represent students' listening construct of interest. If the teacher realizes that there are problems with the assessment, after administering and checking it, he/she should not use scores or interpretations from it; if she/he does, then this is an unethical practice.

Technical level. This listening assessment has the following technical strengths:

It can be argued that the construct is clear; this is a strength because it should help language teachers to design items that target this construct and not others.

The recording for this assessment includes several instances of effects on area and people; thus, the strength is that the text is useful for the construct of interest.

The items are spread throughout the recording and not piled up in a short period of time. This is good, as it can help students focus on relevant information while listening, and not have them worried about having to understand a great deal of information in a short period of time.

The items do not contain any biases towards students, i.e. language used in the items is neutral. The strength, therefore, is that the assessment is not insulting and should not have any negative impact on students' affect.

In general, the items are short, so influence of reading comprehension is low. This is positive because listening is the construct about which the assessment is eliciting information.

In contrast, the following are some aspects that render this assessment problematic:

Items 1, 3, 9, and 10 are not construct-relevant. Specifically, the problems are that they are not collecting information about the intended listening skill; they may be assessing listening but not the specific construct for this assessment.

Item 1 can be answered with information from items 2, 4, 5, and 9, so the problem is that this diminishes the reliability of interpretation: Did students get items right because they have the skill or because they guessed?

The problems with items 2 and 3 are that they have more than one correct answer because options overlap. Again, this creates a violation of reliability. If a teacher assigns a distractor as wrong yet it is right, there will not be score consistency. Additionally, since a right answer is considered wrong, then the assigned interpretation -that the student does not have the skill- is not valid.

Item 7 is both true and false. The first part is true and the second part (have educated visitors) is false, so this is a problem because the item should be either true or false, not both. Also, this item is noticeably longer than the others, which may introduce reading comprehension in this listening assessment; this is a problem because the construct of interest is listening.

Item 9 is neither true nor false. There is no information in the recording for students to judge this item. Changes may be needed but the speaker does not mention anything about this concern, so it cannot be said that the statement is false. This may be problematic because the item is not assessing the construct for this assessment.

Item 10 can be guessed without listening, so the problem is that a correct answer for this item does not imply existence of the construct, i.e. it is not reliable. Henry works in a project where they have visitors, so it is very unlikely that his team does not like to educate them.

Institutional level. Lastly, this assessment partially aligns with Colombian policies for assessment. It partly assesses listening, which is a skill or content in the English as a foreign language class in Colombia and elsewhere. Further, the assessment uses item types (true-false, multiple choice) students can take in the Pruebas Saber 11, but this examination does not include listening as a construct. The assessment is aligned with the school's language learning philosophy as it is meant to assess listening, a communicative skill. Also, the assessment is based on standards from local policies for language learning in Colombia and is clearly aligned with the school's modality. Specifically, the standard for the assessment comes from El Reto (Ministerio de Educación Nacional de Colombia, 2006), a document that states the specific communicative competence students are expected to develop in Colombian high schools.

Since the purpose of the assessment, as stated in Table 4, was to provide feedback on strengths and aspects to improve upon, then the decisions the language teacher made should be more aligned with this overall purpose. Instead of assigning numbers, the feedback from this assessment can be based on what students felt while taking it, including problems they had and the process by which they got items right. However, as there are design problems with this assessment, then its potential to meet the stated purpose is rather limited.

If the instrument were used for self-assessment purposes, and thus aligned with principles in the Decreto No. 1290, other problems could emerge. If students guessed answers correctly, then they would not really be reflecting on their listening skill. Furthermore, since several items are inappropriately designed, students might get confused between what they got right/wrong and what the transcript states.

In conclusion, although some aspects of this assessment are aligned with theoretical, technical, and institutional considerations, there are serious design problems. Because these problems exist, the usefulness of the assessment to gauge listening comprehension and to meet the stated purpose is highly questionable. Failure to meet expected design guidelines can, therefore, lead to inaccurate interpretations of students' language ability. Likewise, if general considerations (see Table 1, for example) are not met in general language assessment design, then their value and usefulness may be limited.

Limitations

There are three limitations that warrant discussion in this paper. To start, language assessment in context may be conditioned by other factors not included in this paper. For example, I do not consider theoretical issues such as summative and formative assessment; technical aspects such as how to write distractors; and institutional considerations such as classroom routines. Thus, the reflection and analysis of the sample assessment may be limited in their scope, especially because the assessment of other language skills is not considered.

Second, the analyses are based only on my perception as a language assessment enthusiast. Other stakeholders may have different views towards the items presented in this instrument and, therefore, provide a different picture of what it represents and how useful it can be. Scholars have suggested that more people should be involved in analyzing tests and their quality for a better picture of their validity (for example, Alderson, Clapham, & Wall, 1995).

Lastly, the analysis was based on one assessment for one language skill. Given space constraints, I could not include assessments for other skills, which may have communicated with a wider readership. For instance, there are specific design considerations for speaking, reading, and writing assessments, namely a clear construct definition, written items and tasks, and items or tasks aligned with institutional policies for language learning. Thus, further practitioner reflections on language assessment design should be welcomed.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Scholars have written extensively about the design of language assessments for classroom contexts. Their work directly targets the needs that language teachers may have when tasked to develop assessments. What seems to be a gap in the literature is that sample assessments are not analyzed against the theory, design instructions, and context where they happen most: the classroom. To contribute to filling this gap, in this paper I first overviewed common theoretical considerations in language assessment at large (e.g. validity and reliability). Then, as a way of illustration, I provided a detailed description of technicalities for the design of listening assessments and included institutional, school-based features that impact language assessment. I used this example to highlight the craft of design and I hope language teachers realize that this level of detail is present in designing assessments for other skills, e.g. speaking.

In the last section, I analyzed one assessment for the target skill by combining theoretical, technical, and institutional dimensions. In doing so, my purpose was to raise awareness of the implications of creating assessments and how, in this process, various expectations converge. The more aligned with these considerations, the more useful assessments can be for the contexts in which they are used.

A related recommendation for practitioners is to use Tables 1, 2, and 3 in this paper as checklists to evaluate the assessments they create. Although the tables are not comprehensive, they offer the best practices in design, as I have synthesized from various authors in language testing. Specifically, teachers can discuss the guidelines as they illuminate their practice and arrive at personal reflections for improvement; teachers working in teams can exchange their assessments and analyze each other's design to see how they align or not with guidelines.

If teachers reflect on the assessments they design and use and consider theoretical, technical, and institutional facets, they will be in a better position to potentiate students' language learning so as to arrive at reliable, valid interpretations of language ability.