INTRODUCTION

The International Labor Organization estimates that global participation in the urban informal economy is 74 % (ILO, 2015). This type of economy consists of a large number of activities without institutional regulations, technologies, or advanced forms of production (Bacchetta et al., 2009). The World Bank maintains that female entrepreneurs make significant contributions to economic growth and poverty reduction around the world (World Bank, 2020). In Colombia, the National Department of Statistics (DANE) revealed that in 2018 informality stood at 48.2 % with salaried female workers representing 62 % of the country's informal economy (Rosales, 2013). Likewise, according to DANE, in 2017 the informal occupation of women was 49.5 % and that of men 44.8 %. In this way, by weighting the data for the past year, the indicator in the country stood at the same percentage for all of 2018 (Portafolio, 2019). For its part, the Universidad del Rosario Labor Observatory (2018, p.2) maintains that "at the gender level, women are predominantly affected by informal employment. This pattern is repeated in all the metropolitan areas of Colombia".

This trend indicates that governments such as the Colombian should understand and address the issue of informality in a strategic way in order to mitigate economic uncertainty in its citizens (Rodriguez & Calderon, 2015). Empirical studies suggest informality in developing countries is linked to tax evasion and preference for capital accumulation (De Soto, 1989). One study between formal and informal labor market entrepreneurs indicates workers prefer informal jobs for their ease (Rauch, 1991). Other women prefer informal jobs for the flexible hours that make it easier for them to reconcile their working life with unpaid care work (Castiblanco, 2018). In Latin-American countries tax evasion resulting from informality is said to slow down economic growth (Loayza, 1996).

Drivers for informality are conceived in a variety of ways by scholars. Some authors argue that rather than self-employment being an indicator of economic empowerment for developing countries, workers resort to it, when opportunitiesof employment in the formal sector are lacking (ILO, 2019); (Beneke et al., 2015). Similarly, organizations such as Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO), maintain the informal economy is comprised of workers (rural and urban) who do not have access to a constant and sufficient salary, as well as all self-employed workers with the exception of technicians and professionals. These include small traders and producers, micro-entrepreneurs, domestic workers, casual workers (for example: polishers and transporters), people who work at home (for example, in clothing or electronics), and street vendors (2015). In contrast, other authors such as De Soto (1989) and Castells, Portes and Benton (1989) understand informality as a mean for carrying out activities away from formality and taxation. The hypothesis of this research leans towards this second contribution.

The advantages of participation in the informal economy for women are said to include dignity and reduction of poverty. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OCDE) considers the economic empowerment of women as the ability to participate in the economy, contribute and benefit from growth processes in order to recognize the value of their contributions, respect their dignity and to have a fairer distribution of the benefits of growth(OCDE, 2011). While for the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (CEPAL), among the most recognized contributions of women's work is the reduction of poverty in their homes, despite the fact that they earn less than men (CEPAL, 2007). Pineda, Urrea, and Arango (2013) when explaining reasons for the higher participation of women in the informal economy in Latin America, argue that the prevailing incidence is that women can have greater relevance, not only due to their link with poverty, but also because of the gender characteristics of said poverty. The authors go on to suggest this could be due to "excess labor" rather than the socio-political nature of the markets.

Following this, it is important to mention the empirical contribution of this paper to the characteristics and causes of informality, based on theoretical contributions that are made in experimental economics literature through studies on honesty and gender. In the case of honesty studies, Nagin and Pogarsky (2001), Mazar, Amir, and Ariely (2008), relate honesty with compliance with a "partially cheating rule". Fischbacher and Föllmi-Heusi (2003), Abeler, Becker, and Falk, (2014), Pruckner and Sausgruber (2013) study the propensity to lie, and Gneezy, Rockenbach and Serra-Garcia (2013) relate the decision to lie with a "liar behavior", and how such decisions increase self-benefit. Fromthese theoretical contributions, experimental economics can empirically reveal how individuals behave when faced with honesty. The same with gender differences in willingness to compete, with studies such as those by Niederle and Vesterlund (2007) and Gneezy, Leonard, and List (2009) which present differences between women and men when competing for positions of power and specialized jobs. However, illegality and informality are not the same, This study argues that informal economy ventures producing illegal ends are subject to greater pressure to transition to the formal economy compared to ventures using illegal means to produce legal products. In contrast, the study suggest that the probability of successful transition from the informal economy to the formal economy is lower for ventures making illegal ends than for ventures using illegal means (Webb et al., 2009).

This study tests De Soto's hypothesis of informality which argues that the motivation for people entering the informal labor market is taxation avoidance.

For this, a field experiment was carried out on 500 women in the city of Bogota. This consisted of a compilation which employs a publication developed in France. Furthermore, in order to identify the characteristics of the research participants, a sociodemographic survey was conducted showing differences in wages, hours, job security and occupations.

To analyze the relationship between the participation of women in the informal labor market in the city of Bogota and tax evasion as argued by legalistic theory, the results of the field experiment were divided into two groups. The first group corresponds to women within formal businesses and the other within informal businesses. That is, those who in the sociodemographic information questionnaire identified that they were employed in the formal labor market or, on the contrary, in the informal labor market in the city of Bogota.

1. METHODOLOGY AND EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

This study adopts the premise that the result of an experiment is, likewise, a model and therefore, the combination of economic theory and experimental work provides easy-to-use tools to further knowledge of the real world. Therefore, by using the experimental method, the objective was to measure the availability of women participating in the informal labor market of the city of Bogota based on preferences due to rational decisions, following De Soto's hypothesis of social disobedience generated by the inclination to avoid tribute (De Soto, 1989).The experiment consisted of two parts. The first part corresponded to a tax evasion game based on Coricelli et al. (2017), the original experiment was carried out with 48 participants and has its own ethics committee approval from Université de Lyon, France.

In this task, participants were asked to randomly select a small paper with the value of a hypothetical income, which they were asked to report, and pay 10 % in taxes. Participants had two options: either to report the true value, or instead a lower value, thereby paying a lower value of tax. Additionally, the participants were aware that they could be audited during the game and in the event of being found misrepresenting their income, they would be subject to a penalty fee.

The objective of this game was to show attitudes towards the payment of taxes and to prove a significant difference between participants who hold formal and informal jobs. The methodological contribution of this research is found in extending and adapting the previous experimental designs conducted in Europe to the city of Bogota, with 500 women. Likewise, the addition of a survey showing socioeconomic characteristics allowed us to explore the reality of the participating women, and therefore, suggest public policies to mitigate informality in the city. These indications are intended to corroborate the work of the legalistic school and therefore accept or reject the hypothesis raised in this investigation.

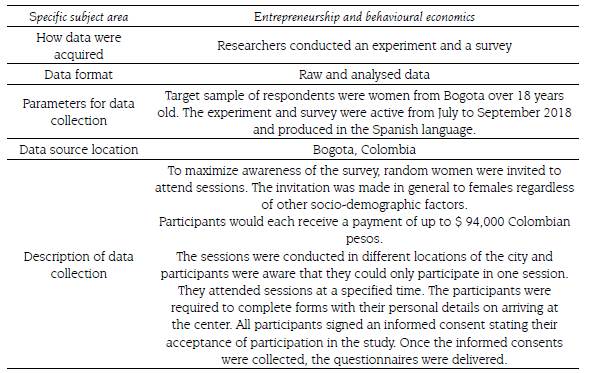

The second part consisted on a sociodemographic information survey. All questionnaires were delivered in person as well as its collection. The questionnaires were numbered from one to five hundred (001-500). Table 1 shows the data specifications.

1.1 Adaptation and validation

The experiment used as reference for the purpose of this research was originally conducted in English. In order to validate the experiment, and once the linguistic adaptation was carried out; the experiment was submitted to the Ethics Committee of the Loyola University, Andalusia, following a pilot test conducted with women located in the south of the city of Bogota, during which 25 surveys were conducted. Through the application of the surveys of the pilot testing, the response time of the respondents, the clarity of the questions and the general design of the experiment were validated. The study found that the questions were clear and understandable for the participants.

1.2 Population and sample size

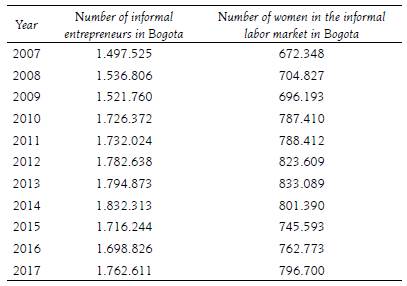

According to figures from DANE, in 2016 the number of women employed informally in the city of Bogota reached 762,773, i.e, a 44.9 %. In 2017 these figures were 796,700 and a 45.2 % respectively (Table 2). The type of sampling was random. The sample size was 384. When the hypothesis tests were conducted, we considered the risks of making type I and type II errors. For that reason, a confidence interval of 95 % and an error one of 5 % has been applied. However, considering the non-response rate for this type of research, in this case a larger sample was sought to ensure reliability. Therefore, the experiment was carried out with 500 women in the city of Bogota.

Table 2 Number of informal entrepreneurs and women in the informal labor market in Bogota

Source: own elaboration with data fromDANE 2017.

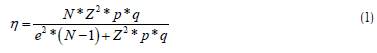

To calculate the sample size, data was taken from the number of women who were part of the informal labor market in the city of Bogota in 2017, using the following sample size formula proposed by Aguilar-Barojas (2005):

η: Sample size; N: Population size; Z: confidence level; p: Probability of success; q: Probability of failure; e: Margin of error

1.3 Ethical approval and registration

The experiment met the ethical requirements regulating the experimentation with human subjects and was considered to be of methodological relevance by the Ethics Committee of the Loyola University, Andalusia, in Seville-Spain, thus being approved in July 2018. Pre-registration and registration were completed in Open Sciences Framework (OSF) and Aspredicted respectively.

2. RESULTS

2.1 Sociodemographic information

Table 3 shows the distribution of respondents by formality and permanence of job with weekly hours worked, marital status, level of education and age. The majority of respondents were informal entrepreneurs: 330 (66 %), while formal were170 (34 %). Of the informal entrepreneurs, the majority have temporary jobs (50.91 %), 28.57 %are married and 34.01 % partnered and 40.7 %are aged between 41-51. The level of education is equal between formal and informal entrepreneurs. Table 4 shows the distribution of respondents by tax attitudes, job description, social security and job history. The formal entrepreneurs paid more taxes, but both consider important to pay taxes. Moreover, 40,00 % of the informal entrepreneurs consider their jobs as secure and have the same occupation as their mothers.

Participants within formal business completed university education, 10.41 % more than women with informal business, which would allow us to argue that the formal market in the city of Bogota absorbs the most qualified workforce and that, perhaps, one of the reasons for the informality of the city, is due to the structural damages of the Colombian economy. In the case of dependents, women with formal and informal jobs have on average the same number of children.

Another important aspect refers to the number of working hours. Participants with informal business work and earn more during the week and their jobs tend to be unsafe due to them working in insecure environments. Women in informal business work 12.48 hours more than women in formal business and, on average, earn $ 118,941 Colombian pesos more per week. In the same way, they consider that they can freely manage their time 11.61 % more than women within formal business. However, they are 6.08 % less satisfied with their trade, and 7.29 % consider their work to be unsafe.

Attitudes towards taxation for participating women within formal and informal business are the same. In contrast to the approaches of the Legalist School, for the women in this research who have formal and informal jobs, paying taxes is of equal importance. However, women with formal jobs argue that they have paid 15 % more taxes, which may be due to the costs of legalizing work.

Participating women within informal business desire to create a new formal business enterprise more than women within formal business. For both groups of participants, the desire to start a formal business is 35.27 % for women within informal business, with women with formal business is 4.14 %. This lack of motivation in women with formal business is primarily due to the fact they consider starting a formal business in the country to be expensive. However, 9.15 % of women with informal business who perceive it to be expensive to start a formal business, are willing to do it more frequently and have attempted to, 7.73 % more than formal ones.

Once more, these results contrast with the approaches of the Legalist School according to which women with informal jobs are described as not wanting to create formal companies in order to avoid taxation. The women with informal jobs in this study indicated a willingness to legally start a business; however, their workforce is not absorbed by the formal labor market, due to its structure in Bogota city.

2.2 Tax evasion game (taxes, audits and penalty fees)

The process of this experiment, as previously stated in section 2., required participants to take randomly a small piece of paper with the value of a hypothetical income which they had to report and pay 20 % in taxes of that amount. Participants had two options: report the true value or report a lower value in order to pay a lower tax value. In the same way, the participants were aware that they could be audited during the game, and in that case, they would have to pay a fine, if they had not reported the true value. The penalty fee was 15 % on income. That is, real income -15 % penalty fee.

The objective of this game was to observe the decisions about payment of taxes and to test, if there were differences in decisions between the participants with formal and informal jobs. The tax game had two rounds and two audits. The results of each round are presented below.

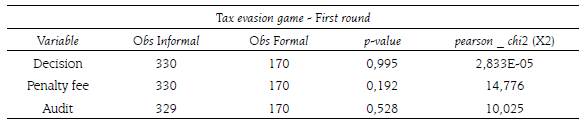

First round: Women in informal jobs were found to prefer reporting their true income and pay required taxes. In the first round, of the 500 women with formal and informal jobs who participated, 93 % of the participants with informal jobs opted to report the true income, and 6.97 % preferred to report a false entry. Likewise, 91.76 % of the participants with formal jobs chose to report a true income and 8.24 % to report a false income. The audit was applied randomly and in the first round, 15.20 % of the participants with informal work and 14.20 % of participants with formal work were manually audited

The probability of reporting a false income was low. That is, both groups of participants made similar decisions about paying taxes, however, women with informal jobs were 2 % more likely to report a higher income and, therefore, pay the corresponding tax. This result opens the discussion that will be raised in the next section of this investigation.

Chi-square statistical tests with p-value of 95 %, confirm that there is no statistical evidence to associate the decisions regarding the tax game with which the participants carry out formal and informal entrepreneurship (Table 5).

Table 5 Chi-square test. Tax evasion game (first round) showing decisions to declare actual earnings and the occurrence of audits and penalties.

Source: own elaboration.

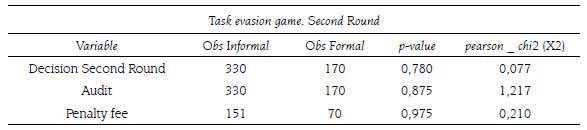

Second round: The experience of the audit in the first round was found to strengthen the willingness of participants to declare their real income in the second round. The rules for the second round were the same as in the first round and all participants had witnessed the random audits and saw some were fined in consequence for reporting inaccurate incomes. In this second round, the auditing percentages were 19.41 % and 18.79 % for participants within formal and informal business, respectively, of which 11 participants, six formal entrepreneursand five informal entrepreneurs, were fined.

Results show that, in the second round, participants continued the trend of reporting true income with increases going from 93.03 % to 96.67 % for informal entrepreneurs, and going from 91.76 % to 95.29 % in formal entrepreneurs, equivalent to three and four percentage points respectively. However, while those women within informal business were found to report true income more than those within formal business, the behaviors remained similar.

Regarding the Chi-square test of the second round, it is confirmed that at confidence levels of 95 % there are no significant differences between the decision to report true income and the formal or informal employment relationship of the participants (Table 6).

Table 6 Chi-square test. Tax evasion game (second round) showing decisions to declare actual earnings and the occurrence of audits and penalties and feelings of shame

Source: own elaboration.

Results of the study were presented in line with a formulated hypothesis as given below:

Ho: Formal entrepreneurs are significantly contributing to the payment of taxes

In the first round, 500 women participated with both formal and informal business. In this round, 93 % of the participants with informal jobs chose to report actual income and 6.97 % preferred to report a false income. Both groups of participants made similar decisions regarding the payment of taxes. Contrary to expectations, women with informal business were 2 % more likely to report actual income and therefore pay the corresponding taxes. Tables 5 and 6 show that Chi-square statistical tests at 5 % (.05) level of significance. The Null hypothesis (Ho) is rejected. The statistical tests of means with confidence values at 95 % confidence confirm that there are no significant differences between the groups. This implies that there is no significant positive difference between formal and informal female entrepreneurs in Bogota.

3. CONCLUSIONS AND LIMITATIONS

It is evident from the official figures of DANE that labor informality in the city of Bogota is predominantly made up of women, and the employment rate shows that men are more likely to carry out formal jobs. These figures lead to the question of why women participate at a higher rate in the informal sector of the economy in the city, assuming, from a gender perspective, that women and men have different opportunities in the labor market.

This quantitative research was aimed at the analysis of the linkage of women to the informal labor market in the city of Bogota, under the hypothesis of the legalistic school led by De Soto (1989) who argues that informality occurs due to individuals desiring to evade taxes and therefore preferring informal jobs. To meet this objective, an experimental field exercise is carried out, as well as a sociodemographic survey of 500 women in Bogota.

Among the primary findings of this research carried out in the city of Bogota, it was found that a significant proportion of the participants had inherited their occupation from their mothers, who taught their profession to their children as a means of earning a living. Regarding education, it was found that informal entrepreneurs have less formal education, work longer hours, and their hourly wage is higher than that of formal entrepreneurs, which may be related to their link to the informal labor market.

Structuralist and institutionalist schools assume that the least qualified labor force is not absorbed, and is therefore moved to informal or underground economies. This is particularly evident in women, who are found to suffer from different forms of discrimination in the labor market due to the gendered division of labor, or in a neoclassical view due to "women's preferences". In conclusion, it is argued that the DANE figures and the data collected in the field on the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants, strengthen the theory of women's work conceptualised by Parella (2000), where working women are situated in the most precarious activities , less socially valued and, and that the inherited trades and altruism in the theories of women's work, agree with the data found.

In the same way, the experiment obtained results that contrast with the theoretical contributions of the Legalist school led by De Soto, whose approach was taken as a hypothesis in this research, regarding the payment of taxes and the possible preference to evade taxes. The option to report the real value of income and pay the corresponding tax was the decision most favoured by the participants. Auditing and penalty fees further underpinned the participants' decisions to report true earnings. Consequently, both participants, those with formal and informal jobs, opted for the payment of taxes, contributing to the rejection of the hypotheses of this research.

This research concludes with the argument that there is no association between the participants' formal or informal business status in tax decisions, at a significance level of 95 %. Therefore, the hypothesis on informality of the Legalist School led by De Soto does not apply to the population of women in central and southern Bogota.

Consequently, women's motivations to join the informal labor market are based on the desire to provide for their families and covering their basic needs. The lack of formal job opportunities evidenced in the unemployment figures and the employment gaps between genders, allow us to affirm that the motivations for linking the female labor force to the informal labor market are not based on personal decisions regarding intertemporal preferences, neitheron values or preferences to avoid tribute; but rather attributed to the need for having economic income and being able to subsist, which is approximated with the theoretical contribution of the ILO (2019).

To conclude, in order to overcome the limitations of this study, the authors propose that future experiments might be carried out with the use of computers, since this research was carried out on pencil and paper, in order to avoid errors in data transcription. Future research agendas may consider an alternative approach to the relevance of access to formal education in women, since as evidenced in this work, women with informal jobs have less formal education and this is likely to be a determining factor in the structural problem of the formal labor market. This line of enquiry could be compared to men's education in order to establish the importance of education in the employability of labor and its influence on informality.

3.1 Proposal for mitigating the informality

As mentioned above, this research proposes education offers as an alternative pathway for informalfemale workers. For this, an increase in access to education is suggested. This is supported by previous studies carried out in Latin-America and Colombia. For example, a study carried out in Argentina shows that informality is a response to the inability of the formal sector to occupy all available labor, and education is considered a fundamental factor in differentiating and selecting an individual for formal employment (Beccaria & Groisman, 2008).

In the case of Colombia, researchers found through empirical evidence that the marginal effect of education on informality is negative (Uribe et al., 2002), demonstrating that people who carry out informal activities lack formal education (Menni, 2004).In cities such as Barranquilla, Cartagena and Monteria, factors such as education, age, marital status and being head of household influence the probability of being an informal worker (Uribe et al., 2008). In the case of the young population, education is the means that facilitates their entry into the labor market, with the culmination of secondary studies and the design and implementation of educational strategies or plans (Vasquez & Ospino, 2009).

Among the results obtained in this research, several data regarding education are concerning. The first of these is that 40 % of the participating women with informal jobs have the same occupations as their mothers. This is not a negligible percentage if the percentage of females represented in informal occupation in Bogota for 2018, which was 45.2 %, is taken into account.

Therefore, to ensure that informality is not an inherited occupation and that the children of women who have informal jobs are not limited to the same job as their mothers in the future, it is suggested that formal education at all educational levels should be expanded. Taking as a reference that education is a conditioning factor for social change (Niebles, 2005). It is important to mention that in the results of this research it was found that 91.54 % of women of this study with informal jobs did not wantedtheir children to have the same occupation. This expansion of the coverage of public education in the country must be at all educational levels and in both, face-to-face and distance, learning options. This would allow future generations of informal workers to have access to better working conditions.

For women who carry out informal work in the city of Bogota, it is proposed that the district provides facilities to access formal education with the support of the Secretary of Education and the Ministry of Education. As evidenced in this research, of the women with informal jobs, only 26.38 % have fully completed the highest level of education, which presents a barrier to accessing formal employment. It is suggested that the District Secretary for Education provides spaces for these women to complete their formal basic middle and high school education in District schools, at night or on weekends, and that transportation subsidies be granted to aid women in attending classes.

For those who wish to receive training in specific technical labor courses, it is further proposed that SENA (Colombian National Training Service) offers more affordable courses to women who work informally, either by taking these courses with agreements in district schools or with the support of community actions by neighborhoods of the city, allowing instructors or professors to go to each locality.

Additionally, it is suggested that women with informal jobs who wish to enter higher education, can do so through the support of the Ministry of Education, with the granting of scholarships, as well as subsidies for books and materials and preferential access to public education. At the culmination of their baccalaureate, technical and professional studies, women who currently hold informal jobs will become skilled workers, who are able to enter the formal labor market either as employees or as entrepreneurs and therefore contribute to their sons and daughters having a different future rather than entering the informal labor market. Consequently, these proposals that aim towards increasing the duration of female participation in education are considered to have greater potential to mitigate the informality of current and future female workers in the city of Bogota.