Introduction

Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage syndrome is characterized by the presence of blood in the pulmonary alveolus from arterioles, venules and pulmonary capillaries, as a consequence of a lesion of the alveolar wall and without an endobronchial alteration. Its presentation includes a classic triad of hemoptysis, anemia and diffuse alveolar infiltrates. It's a rare but potentially fatal entity and there are no clear data on its real incidence in the pediatric population.

Recently, Rhinovirus infection has been postulated as a cause of severe respiratory infection, mainly in patients older than one year and the severity of the disease seems to be related to viral coinfection. In 70% of the cases the infection by human Bocavirus presents coinfection with Rhinovirus; some studies suggest that this coinfection is associated with serious infections of the lower respiratory tract, especially in immunocompro-mised patients; however, there are no reports in the literature as causal agents of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage syndrome in children, except in immunocompetent patients 1-3.

We report the case of a pediatric patient, immunocompetent, with diffuse alveolar hemorrhage syndrome. For the presentation of this case, the written consent was requested from the patient's mother who authorized the publication of the clinical history data and the relevant paraclinical findings.

Clinical case

She was a four-year-old girl, previously healthy and without significant clinical history, with five days of respiratory symptoms: hyaline rhinorrhea, productive cough and fever of 38.5 ° C. At 48 hours, she was admitted to a hospital with signs of respiratory distress and a presumptive diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia.

The chest radiograph showed signs of pneumonic consolidation in the right middle and upper lobes. Oxygen therapy and treatment with ceftriaxone and clindamycin were started.

Due to her respiratory deterioration she was transferred to a center of higher level of complexity (level 3), entering to the pediatric critical care unit in ventilatory failure (arterial oxygen saturation -SatO2- of 75% with inspired fraction of oxygen -FiO2- at 100%), requiring oro-tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation was initiated (assisted / controlled mode, respiratory rate: 20, PEEP: 8, PIP: 25, FiO2: 50%). The paraclinics reported: normal blood count, C-reactive protein 16 mg/dL (normal value 0 - 0.5), renal function and uroanalysis were normal.

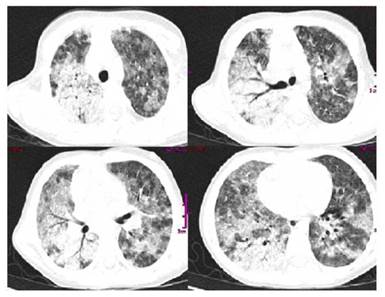

A new chest X-ray showed progression of the opacities, so were performed blood cultures and nasopharyngeal swab for the detection by immunofluorescence of respiratory syncytial virus and influenza A and B viruses, whose results were negative. A computed tomography of the thorax was requested, showing generalized ground-glass lesions with parenchymal consolidation of multifocal pulmonary appearance, suggestive of alveolar hemorrhage associated with a possible infectious process (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Chest CT scan. Bilateral multifocal frosted glass pattern. Pneumonic parenchymal consolidation in the right lung

The patient presented rutilant bleeding by tracheal tube with hemoglobin drop of 4 gr/dL in relation to the admission value, severe respiratory acidosis (pH: 7.2, pCO2: 68, pO2: 123, HCO3: 21, satO2: 94%; be: -5). Before clinical decompensation, she was sedated and relaxed with protective ventilatory management and antibiotic therapy was scaled with vancomycin and piperacillin tazobactam, as well as osel-tamivir. An immunological profile was requested, initiating empirically pulses with methylprednisolone and referred to a more complex level of care (level 4).

In this new institution she entered in regular conditions, with conventional ventilatory support, compensated gasometry, normal coagulation times; repeated infectious tests and immunological profile and echocardiogram was performed that was reported normal; also kidney and liver functions were normal.

Neumology service performed a fibrobronchoscopy that reported: normality in the anatomy of the bronchial tree, with hyperemic mucosa and diffuse mild bleeding, coming from all the lung segments. Samples were taken in the bronchoalveolar la-vage for microbiological studies (Table 1). Given the findings, a syndrome of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage with an infectious cause to be defined was considered as the first etiological possibility.

In the evaluation performed by pediatric rheumatology no skin lesions, vasculitic lesions or joint alterations were found and the immune profile was negative for all tests (anti-cardiolipins, rheumatoid factor, antiphospholipid antibodies, antinuclear antibodies, total extractable antinuclear antibodies, anti-DNA, anti-cytoplasmic antibodies of neutrophils -ANCAS-, anti-basal membrane antibodies and human immunodeficiency virus). However, they indicated five-day treatment of methylprednisolone in pulses.

Diagnostic support was requested from the microbiological laboratory in order to discard possible infectious agents: blood cultures, urine test, bronchoalveolar la-vage, purified protein derivative, which were all negative; while the polymerase chain reaction in pharyngeal swab was positive for Rhinovirus and human Bocavirus (Table 1).

Studies by Immunopediatrics (immune profile, cytometry and lymphocyte subpopu-lation) ruled out immunodeficiency. The patient had marked improvement allowing extubation at 72 hours, leaving the intensive care unit on the fifth day, discontinuing vancomycin and completing seven days of piperacillin / tazobactam and was discharged without apparent sequelae.

Review of the literature

In this report, a four-year-old girl, immunocompetent, who presented alveolar hemorrhage with clinical criteria and images such as chest CT, fibrobronchoscopy and bronchial-alveolar lavage confirmatory of the disease. The etiological search ruled out an immune cause and the results of microbiological laboratory and molecular biology led to conclude that the presentation of the syndrome was secondary to coinfection by Rhinovirus and human Bocavirus.

The syndrome of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage is characterized by the presence of blood in the alveolar space, coming from arterioles, venules and pulmonary capillaries, as a consequence of the lesion of the wall of the alveoli 1. It is an uncommon but potentially lethal entity in children, although there is no clear data on its actual epidemiological behavior 1-3.

It is manifested as the association of hemoptysis, pulmonary opacities on chest radiography, cough of acute or subacute onset, anemia and hypoxemic respiratory distress, because of the accumulation of intra-alveolar red blood cells, from the alveolar capillaries and, less frequently, of the pre-capillary arterioles or of the post-capillary veins 4-6. Up to 40% of cases might occur without hemoptysis and with mortality of 20 to 30%.

In immunocompetent patients have been found more than 100 causes of the syndrome. They might be grouped into three large groups (autoimmune, cardiovascular and of unknown origin). However, occasionally the etiology remains unknown (Table 2) 7-9.

To confirm the diagnosis, early bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage is indicated, finding hemosiderin in the alveolar macrophages; however, the sensitivity is low to define the cause of the hemorrhage 1,9-11.

In immunocompetent patients, pulmonary infection is rarely associated with the syndrome; however, there are more reports of infectious diseases that trigger severe disease and alveolar hemorrhage, with worse outcomes 4,5.

Cytomegalovirus, Adenovirus, Aspergillus spp, Mycoplasma spp, Legionella spp, Hantavirus, Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Strongyloides spp. Infections are more frequent in immunodeficient patients; whereas in immunocompetent patients the most associated infectious etiology is Influenza A / H1N1 Virus, Dengue Virus, Leptospira spp, Plasmodium spp and Staphylococcus aureus, in addition to sometimes undetected viral infections behaving as a serious and rare complication 8,12-14.

Recent advances in molecular techniques have allowed the diagnosis of emerging viral pathogens such as Rhinovirus, Metapneumovirus, Influenza A / H1N1, HBoV, Polyomavirus and Parechovirus, among others, in severe respiratory disease 3,15-16.

The human Rhinovirus is one of the most important causes of respiratory infections, mostly associated with common cold, especially in children, with those over one year more susceptible and with more severe affection 14,16,17.

Also, human Bocavirus infections, due to their ability to persist long time in the mucosa of the respiratory tract, seem to have a more aggressive behavior when it is associated with another virus, especially with Rhinovirus, reaching co-infection rates of up to 83%, acting as exacerbating factor and increased the severity of respiratory infection by other pathogens 18,19,21.

Having as factors of serious illness elevated levels of viral load, coinfection with other viruses, children older than one year and hospitalized patients or suffering a chronic disease; although studies have detected a high rate of carriers, which makes it difficult to conclude that this alone, would have a preponderant role in the etiology of acute respiratory disease 20,21.

Hemoptysis is the major clinical sign, which might develop acutely or over a period of days to weeks; however, it may be initially absent up to 33%. Some patients have anemia secondary to bleeding, acute respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation. The severity of the disease is variable and, in some cases, fatal 1,5-7.

Chest radiography may show diffuse alveolar opacities of alveolar occupation and acute onset. Chest tomography may show nonspecific findings; however, it is common to see different degrees of frosted glass pattern occupying much of the lung fields. Histopathology is characterized by intralveolar red blood cells and fibrin, with accumulation of hemosiderin within the macrophages (siderophagia) 4-6.

Once the diagnosis is made, the cause must be established to begin immediate treatment and improve outcomes. Recurrent episodes of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage syndrome produce pulmonary interstitial fibrosis and restrictive functional changes 4,5.

Lung biopsy will clarify the etiological cause, immunofluorescence can provide information about immune deposits and the polymerase chain reaction will define the infectious etiology 1,7,15.

The treatment is aimed at establishing the basic diagnosis, providing respiratory support and preventing the progression of microcirculatory damage, typically with steroids and different immunosuppressive agents 11. In some cases, advanced therapies such as rituximab and plasmapheresis will be required, especially in cases with associated vasculitis and there is no response to steroid management 19.

Conclusion

The diffuse alveolar hemorrhage syndrome is an entity with high Morbi-mortality and although the main etiology is due to autoimmune diseases, reports of non-immune causes are becoming more common, specifically due to respiratory infectious processes, where viruses take great relevance. There are no reports in the literature of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage syndrome due to Rhinovirus and Human Bocavirus, alone or in coinfection, much less in immunocompetent patients.