INTRODUCTION

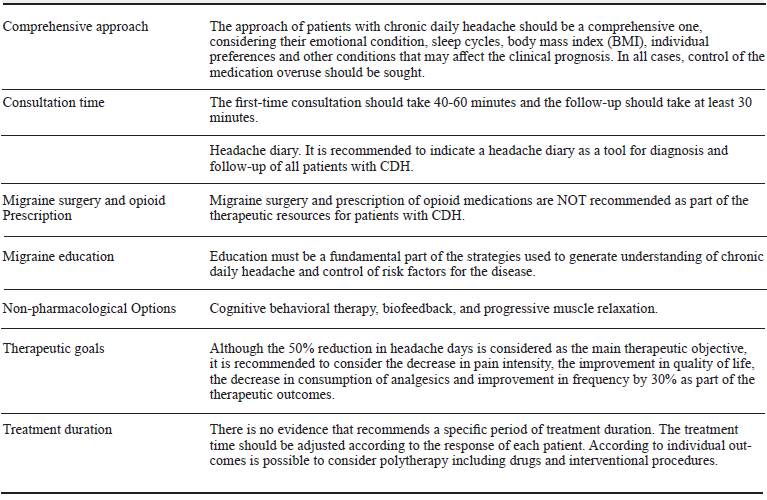

At least 50% of the general population has suffered from headache during the last year 1. Although chronic tension-type headache represents the most prevalent etiology, migraine is the entity with the greatest impact related to disease burden 2,3. Both entities can evolve to chronic daily headache (CDH), which is characterized by reaching a headache frequency equal to or greater than 15 days per month during the last three months 4,5. This syndrome presents a population prevalence of 2.6%, 1.1% for chronic migraine (CM) and 0.5% for chronic tension-type headache (CTTH) 1. In Latin America a prevalence between 5.12 and 7.76 has been reported 6. The CDH group is complemented by hemicrania continua (HC) and new daily persistent headache (NDPH), members of groups III and IV of the International Headache Society (IHS) classification, which represent 0.07% and 1.15%, respectively, in the clinical population 6. Although the IHS classification does not directly consider the concept of CDH, it does define the diagnostic criteria of each of these entities, which allows its application to clinical practice (table 1). According to the data of disease burden and therapeutic refractoriness of the CDH, this syndrome generates a high impact on the general population, measured in years lived with disability, excessive use of analgesics, decrease in labor production and role restriction 7-9.

Table 1 Diagnostic criteria based on The International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd Edition (ICHD 3).

Source: 4.

Source: authors

Delphy methodology consists of a research technique designed to reach agreements on issues in which there is uncertainty. It is based on the meeting of a group of experts who, by filling out a predetermined questionnaire, provide answers to previously designed questions in search of agreements in related behaviors 10. Its use in health sciences allows obtaining consensus behaviors applicable to clinical practice 11.

The Grade system (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) is a methodology based on a sequential analysis of evidence that determines its quality, its advantages, its disadvantages, direction, and strength of the recommendation obtained from this methodology 12,13.

Taking into account the need to establish therapeutic behaviors for the entities that make up the CDH group, the working group of the Colombian Headache Committee, which is part of the Colombian Association of Neurology (ACN in Spanish), presents the recommendations for the treatment of chronic migraine, chronic tension-type heada- che, hemicrania continua, and new daily persistent headache.

The thematic components with available evidence through systematic review are presented after the analysis with the Grade methodology, using PICO (patient,intervention, comparison and outcome) questions. Those without available evidence are presented through consensus agreements under the Delphi methodology.

METHODOLOGY

The ACN selected the methodological group and the experts that participated in the consensus according to their professional career, academic training, and willingness to participate. The evidence for the generation of the recommendations was selected according to the process described in Figure 1. This evidence was evaluated and integrated into the recommendations through the consensus method. In the questions in which evidence of adequate quality was identified, the generation of recommendations was obtained according to the Grade methodology. The identification of evidence and the consensus method were carried out in the following stages:

Stage 1. Prioritization of topics

The methodological group developed a first list of questions about the treatment of each of the four groups included in the definition of CDH. This list of questions was evaluated by a subgroup of the group of experts who rated the importance of including each question on a seven-point Likert scale (from nothing relevant to totally relevant).

The questions that obtained an interquartile range of 7 to 9 were considered for conducting systematic reviews 15.

After determining the questions related to each topic, the developer group created a search strategy based on the combination of the terms used for the denomination of the different types of chronic daily headache and the filter with the best balance of sensitivity and specificity for the identification of systematic reviews on the OVID platform. In the interventions that required searches for primary studies, no restrictions were used by type of study. All searches were carried out in the OVID version of the Medline, Embase and Cochrane databases and were limited to studies conducted in humans and published in English over the past 20 years (figure 1). Systematic reviews were evaluated by two independent evaluators who rated them using the Amstar methodology; those with a moderate and high evidence score were included in the evidence material considered for this project.

Stage 2. First round of consensus

The methodological group sent a series of preliminary recommendations and their respective tables of evidence individually to each expert via email. Each member was asked to rate their degree of agreement with each proposal, using a seven-point Likert scale. Additionally, each expert had the opportunity to openly write their comments on each preliminary recommendation. Proposals in which an interquartile range of 1 to 3 was obtained were considered as not approved by consensus and those that obtained an interquartile range of 7 to 9 were considered proposals approved by consensus. The proposals that obtained different interquartile ranges were taken to a second round of qualifications.

Stage 3. Second round of consensus

The proposals that obtained interquartile ranges between 4 and 7 in the first round of the consensus were sent back to each expert via email. Together with these proposals, each participant was sent a tabulation of the results of the qualifications in the first round and the comments made anonymously by the experts. Each of the new proposals from this group was rated individually by each participant. Proposals in which no consensus was obtained in the second round of ratings were taken to consensus through the nominal group method.

Stage 4. Nominal group

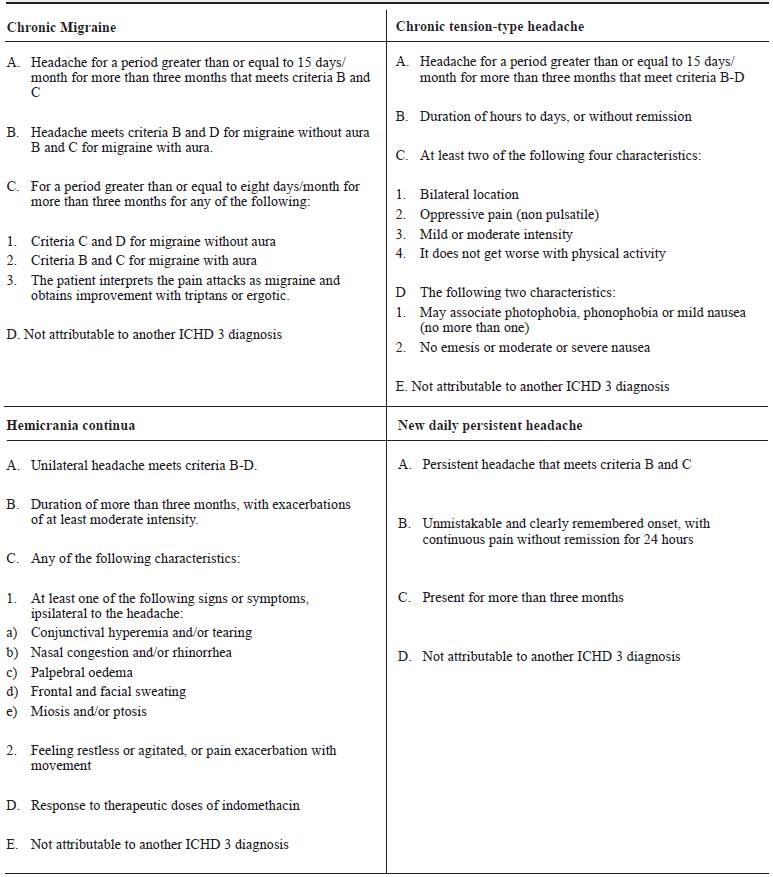

For the realization of the nominal group, the thematic leaders of each subgroup (one for each subtype of CDH) met to discuss each of the issues on which no consensus was reached. In this stage, arguments based on experience and theoretical sources were presented until reaching the consensus of the majority of the participants. At the end of the meeting, the group of experts evaluated the wording of each of the recommendations for inclusion in the final manuscript, including the general principles of the therapeutic approach of the CDH (table 2).

CHRONIC MIGRAINE

1. Is botulinum toxin A (onabotulinum toxin A) effective and safe for the treatment of patients with chronic migraine?

PICO

Population: patients with chronic migraine

Intervention: botulinum toxin (onabotulinum toxin A) 155-195 U

Comparison: placebo

Outcome: headache days/month reduction

Evidence analysis

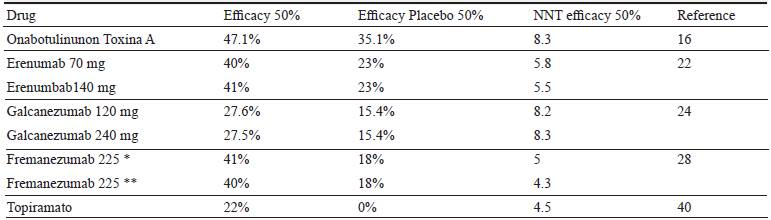

Botulinum toxin A - onabotulinum toxin A (ONABOT A) was studied in two randomized controlled clinical trials, PREEMPT 1 and PREEMPT 2. In total, 1384 individuals between 18 and 65 years of age were studied, with a dose of 155-195 u, in 31-39 places of the scalp, compared with placebo and baseline frequency vs. week 24. In PREEMPT 1, the number of headache episodes was analyzed as primary outcome, and there was no statistically significant difference vs. placebo (5.2 vs. 5.3; p=0.344). However, secondary outcomes, headache days (p=0.006) and migraine days (p=0.002) showed a significant reduction compared to placebo 14. In PREEMPT 2 the number of days with headaches was chosen as primary outcome, and superiority of ONABOT A was evidenced vs. placebo (-9.0 vs. -6.7, respectively, p<0.001) 15. The secondary outcomes in PREEMPT 2; migraine days frequency, frequency of days of moderate to severe intensity, cumulative monthly hours of migraine, proportion of patients with severe HIT-6 and frequency of headache episodes showed favorable results that support ONABOT A compared to placebo; p<0.05 in all cases. Based on the data obtained from the pooled analysis of both studies 16 (onabotulinumtoxin A 47.1% vs. placebo 35.1%; p<0.001), an NNT of 8.3 was calculated to achieve 50% improvement. Both studies showed a favorable safety profile, with a low probability of withdrawal due to side effects, NNH: 38. These findings were confirmed in a pooled analysis that showed a decrease in the incidence of adverse effects when comparing cycle 1 with 5 17. In the long-term follow-up, the COMPEL study 18 analyzed 716 patients aged between 18 and 76 years and showed a reduction of 9.2 and 10.7 days of headache at week 60 and 108, respectively, p<0.0001, from a record of 22 days/ month at baseline. These results match with the 56-week analysis based on the pivotal studies 14.

Clinical considerations

ONABOT A is effective in the treatment of chronic migraine with more evidence when comparing the reduction in headache days/month vs. migraine days/month. Studies show limitations that are represented in the risk of unmasking due to aesthetic effects in treated patients 19.

According to the recommendation of experts, therapy with ONABOT A should be initiated in patients who meet the ICHD 3 criteria for chronic migraine, after at least two medications at a maximum tolerated dose for a period of two months have failed. In those patients without response to the first cycle, the opportunity to perform cycle two and three can be considered, taking into account that the probability of obtaining 50% efficacy is 11.3% and 10.3% for each cycle, respectively 20; individual time and clinical conditions should be part of the analysis factors when considering this choice. If a responding patient is considered, it is recommended to maintain stable doses and intervals of application every 12 weeks. After the first year it is possible to determine the following cycles at 16 and 20 weeks, respectively, with new adjustments according to the clinical response in each case. According to Grade recommendations, the evidence strongly favors the reduction in headache days and migraine days, with partial evidence in migraine episodes (table 3).

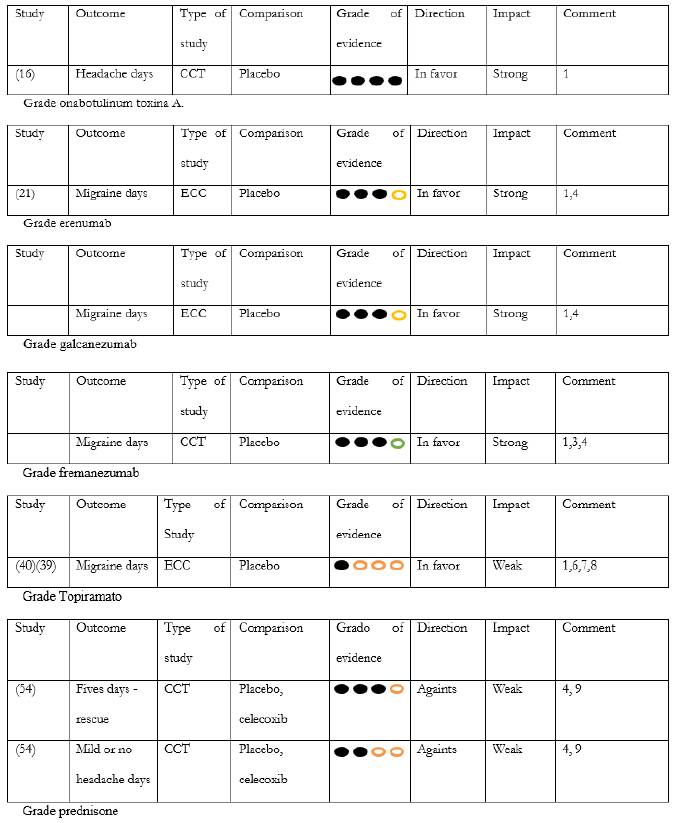

Table 3 Grade system, therapeutic options in chronic migraine.

CCT: controlled clinical trial

1. Study sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry

2. Risk of inconsistency

3. Risk of inaccuracy

4. No clarity in the selective outcome report

Acta Neurol Colomb. 2020; 36(3): 150-167

5. Unclear generation of random sequences

6. Unclear allocation concealment

7. Unclear intervention masking

8. Significant losses to follow-up (> 20 %)

9. No intention-to-treat analysis was carried out

Source: authors.

Final Recommendation: ONABOT A is recommended for the treatment of patients with chronic migraine. Quality of evidence for headache days: high, recommendation: strong

2. Are anti CGRP drugs effective and safe to treat patients with chronic migraine?

PICO

Population: patients with chronic migraine

Intervention: erenumab 70 and 140 mg

Comparison: placebo

Outcome: migraine days reduction

Evidence analysis

Two clinical trials have proven the efficacy of erenumab in patients with chronic migraine. The first one is a phase 2 study with 667 patients and an average migraine day of 18.2, comparing placebo (n=286) vs. erenumab 70 mg (n=191), or erenumab 140 mg (n=190) with an age range of 18-65 years and a 12-week follow-up. Compared to placebo, erenumab 70 and 140 mg reduced migraine days/month by 2.5 days (-2.5, 95%, CI - 3.5 to -1.4) p<0.0001 in both cases. The probability of achieving improvement of 50% or greater was 40%, 41% and 23% in the doses of 70 mg, 140 mg, and placebo, respectively, p<0.001 in both cases. The calculated NNT was 5.8 and 5.5 for the doses of 140 and 70 mg, respectively, vs. placebo. Both doses also demonstrated a significant decrease in the number of days using analgesics. In the analysis of cumulative hours of headache per month there was only statistical significance for the dose of 140 mg, p=0.0296. The probability of withdrawal due to collateral effects was less than 1% 21.

The second study is part of a subgroup analysis in which the same doses are compared against placebo, using as a primary outcome the proportion of patients with a 50% reduction in the frequency of migraine days/month after 12 months of treatment in patients with failure to more than two medications, more than three, excluding failure to more than four therapeutic options. In the failure to two or more treatments group, the primary outcome was achieved in 34.7% and 40.8%, at doses 70 and 140 mg, respectively, vs. 17.3% for placebo. In the failure to three or more treatments group, this percentage was reached in 35.6% in doses of 70 mg and 41.3% in doses of 140 mg, vs. 14.2% for the placebo group (p=0.001 in all cases, in both doses of each group when compared against placebo). The comparison of both doses against placebo in naive patients showed no statistically significant differences. The report of side effects was low in both analyzes, with a probability of withdrawal of 1.6% or less in both groups for each dose 22.

In an observational study with 65 patients in real clinical practice, a decrease of 12.2 and 15 migraine days/month was documented at week 4 and 8 when compared with the baseline. The response >50% was reached in 68.2%, 87.5% for the same periods. The study reported no significant side effects 23.

Final recommendation: erenumab is recommended for the treatment of patients with chronic migraine. Quality of evidence: moderate; recommendation: strong.

PICO

Population: Individuals with chronic migraine

Interventions: Galcanezumab 120 mg + loading dose 240 mg and Galcanezumab 240 mg without loading dose.

Comparison: Placebo.

Outcome: Migraine days per month.

Evidence analysis

A phase III randomized clinical trial with participants between 18 and 65 years of age, with an average of 19,4 migraine days, treated as follows: 240 mg loading dose followed by 120 mg monthly dose (n:278); 240 mg monthly dose without loading dose (n:277); monthly placebo (n: 558). Both dosages of Galcanezumab resulted in a higher rate of success in reducing the migraine days per month, as follows: placebo -2,7; 120 mg Galcanezumab -4,8; 240 mg Galcanezumab -4,6 (p <0,001 for each dose relative to placebo). The probability of improving at a 50% rate was calculated to be 15,4% for placebo; 27,6% for 120 mg; and 27,5% for 240 mg 24. The number needed to treat (NNT) calculated for 120 mg and 240 mg vs. placebo stood at 8,2 and 8,3 respectively. Furthermore, this trial evidenced statistically significant differences between the 120 mg and 240 mg doses in the reduction of days with headache, hours without pain and migraine, p under 0,005 in all cases. Quality of Life (QOL) scales and the likelihood of reduced use of analgesics were significant only at the 240 mg dose. There were 6 placebo-related withdrawals and 5 Galcanezumab-related withdrawals. There were no significant differences in laboratory tests when comparing Galcanezumab vs. placebo 24.

One study compared Galcanezumab vs. placebo in patients with failure to > 2 and reported a reduction of 5.35, 2.77 and 1.01 migraine days per month for the 120mg, 240mg and placebo doses, respectively. A reduction of 5.35, 3.53 and 2.02 at doses of 120 mg, 240 mg and placebo, respectively, was observed in the group of failure to > 1 preventive, with p less than 0.05 in all cases. In the group without previous failure, the difference was statistically significant only at a dose of 240 mg 25. There was a decrease in the number of migraine days per month at month three in patients with therapeutic failure to onabotulinum toxin as follows: -3.91, -5.27, -0.88 for Galcanezumab 120mg, Galcanezumab 240mg, and placebo, respectively 26. Open-phase follow-up in 9 patients with an average of 18.38 ± 3.74 migraine days showed reductions of 5.38 ± 4.92 at weeks 1-4 (p = 0.001), 4.75 ± 4.15 at weeks 5-8 (p = 0.001), and 3.93 ± 5.45 at weeks 9-12 (p = 0.014). There was no statistically significant difference when comparing the migraine days per month 12 weeks after completing the open phase against the last 4 weeks of this phase 27.

Final recommendation: Galcanezumab is recommended as a treatment for patients with chronic migraine. Quality of evidence: moderate; recommendation: strong.

PICO

Population: Individuals with chronic migraine

Interventions: Fremanezumab 225 mg - loading dose 675 mg.

Comparison: Placebo.

Outcome: Headache days per month.

Evidence analysis

A phase 3 clinical trial with 1130 participants suffering from chronic migraine having an average of 13.1 headache days per month was conducted to compare the following: 225 mg subcutaneous injection applied monthly and a loading dose of 675 mg (379); 225 mg subcutaneous injection applied monthly and a loading dose of 675 mg; and placebo (375).

The average reduction of headache days per month when comparing the baseline vs. week 12 was 4.6± 0.3 when administering the drug on a monthly basis, 4.6± 0.3 when administering the drug in a quarterly basis, and 2.5 ± 0.3 when administering the placebo (p<0.001 in both groups vs. placebo). The difference in days between the monthly dose and the placebo was 1.8, while the difference in days between the quarterly dose and placebo was 2.1. A similar result was found when comparing fremanezumab vs. placebo in patients with therapeutic failure to other preventative treatments including onabotulinum toxin 28. Improvement at a rate of 50% was reported to be 38% for the quarterly injection, 41% for the monthly injection, and 18% for the placebo (p<0.001 in both groups vs. placebo) 29. NNT: 5 for the quarterly injection, and NNT: 4.3 for the monthly injection. These differences have been documented from week 1 following the start of treatment with doses of 225 mg (p:0.048) maintaining efficacy in the second and third week up to month 3 (p:0.04, p:0.025 and p<0.001, respectively) 30. This effect is maintained when fremanezumab is part of the adjuvant therapy 31. The analysis of secondary outcomes revealed significant differences in the number of migraine days per month, the number of days using acute treatments, and the disease disability score as measured by the Headache Impact Test (HIT) 6 (p<0.001 in all cases). Serious adverse effects were reported in 2% of patients who received placebo and 1% of those who received fremanezumab. Withdrawal for side effects due to treatment was reported in 3% of patients who received fremanezumab vs. 2% of patients who received a placebo 29.

Final recommendation: fremanezumab is recommended as a treatment for patients with chronic migraine. Quality of evidence: moderate; recommendation: strong

Clinical considerations

The consensus analysis recommends prescribing Erenumab, Galcanezumab or Fremanezumab to patients with chronic migraine following the failure of two first-line drugs at maximum tolerated doses for a minimum period of two months 32. The efficacy analyses in real life mirror those reported in pivotal trials (table 4). In these observations, super-responder rates (70-100%) have been reported in 14 to 18% of cases 33. In case of previous treatment with ONABOT A, it is recommended to apply at least two cycles before considering these therapeutic alternatives.

Table 4 Comparative efficacy preventive treatments in chronic migraine. Source: authors.

*monthly

**quarterly

Although the available results for Eptinezumab revealed statistically significant differences compared to the placebo, the source trials were designed for dose exploration, thus Eptinezumab has not been included as part of the recommendations derived from this consensus 34.

In terms of safety, no significant cardiovascular effects have been reported in phase 2 and 3 clinical trials. These findings are consistent with safety data of Erenumab in individuals with stable angina 35 and high blood pressure in combination with Sumatriptan 36. However, the length of the observation periods in these trials is not enough to extrapolate conclusions to clinical practice, which is why this type of medication is not recommended for patients with uncontrolled cardiovascular risk factors. Additionally, these drugs are not to be prescribed for pregnant or lactating women or individuals with severe mental disorders 32. Caution should be exercised in patients with rigid rheumatic diseases and in cases of recent bone injury 37. There is still no information on the effect of anti CGRP on the HPA (Hypothalamic pituitary axis) axis, and therefore these drugs are not recommended for individuals who have not reached hormonal maturity 37.

Regarding tolerability, real-life patient follow-up has revealed an incidence of constipation, fatigue, and depression at 6-20%, 4-6% and 3-6%, respectively 33. Erenumab, Galcanezumab and Fremanezumab may be prescribed along with preventive oral medications, although treatment with ONABOT A has been recommended before starting an anti CGRP 32. The complementary mechanism of action 38 along with the increase in efficacy reported without impact on safety could allow this combination in selected cases 33. Based on expert recommendations, this consensus suggests maintaining therapy for 6-12 months. Further recommendations will be considered as clinical developments and new evidence come to light 32.

3. Is topiramate effective and safe for the treatment of patients with chronic migraine?

PICO

Population: patients with chronic migraine

Intervention: topiramate

Comparison: placebo - other interventions Outcome: migraine days/month reduction

Evidence analysis

Two multicenter, randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trials have shown topiramate's efficacy in the treatment of patients with chronic migraine. The first of these, which took into account 306 individuals (topiramate, n=153; placebo, n=153), showed a reduction in migraine headache days (topiramate -6.4 vs. placebo -4.7, p=0.010) (39). The second study included 59 patients and reported a decrease of 3.5 migraine days/month from a baseline of 15.5 days/month, compared with an increase of 0.2 days/ month from 16.4 in the baseline (p=0.02), the percentage of patients with 50% improvement was 22% for patients with topiramate and 0% for patients with placebo (40). In both studies, paresthesias were reported as the most frequent side effects.

Clinical considerations

The recommended dose, according to clinical trials, should be 100 mg. This dose is based on the results obtained in the clinical trials in episodic migraine in which a balance of greater efficacy and safety was demonstrated, however, according to the clinical response it is possible to reach 200 mg 41. The results obtained in both clinical trials included patients that presented excessive use of analgesics, a variable in which no significant efficacy was demonstrated when compared with placebo, which may be due to the calculation of power in the sample studied. This factor should be considered relevant in clinical practice in those patients in whom it is not possible to significantly reduce the frequent consumption of analgesics. The efficacy of topiramate has been reported equivalent to that obtained with ONABOT A in the global determination of improvement, headache-free days and MIDAS scores at week 12 of treatment 42, Table 4. Other factors to take into account regarding safety are memory impairment, which occurs more frequently with doses greater than 100 mg, urolithiasis, glaucoma and weight loss 41.

Final recommendation: topiramate is recommended for the treatment of patients with chronic migraine. Quality of the evidence: low; recommendation: weak.

4. What other pharmacological options can be considered as part of preventive treatment in patients with chronic migraine?

Evidence analysis

Amitriptyline: in a dose of 25-50 mg, amitriptyline in an open study showed therapeutic equivalence to ONABOT A 250 UI, in the probability of improvement 50% at frequency, 67.8% vs. 72% (p=0.78; RR=0.94; CI=0.11-8). Nor were there significant differences in pain intensity and use of analgesics. Weight gain was described in 11.8% of patients treated with ONABOT A vs. 58.3% of those treated with amitriptyline (p=0.0001). Drowsiness was reported in 4% of patients with ONABOT A vs. 52.7% of those who received placebo (p=0.0001). Constipation occurred in 0% of the ONABOT A group vs. 38.8% of the amitriptyline group 43.

Fhinarizine: an open study that compared the efficacy measured in days/month of headache in subjects with and without excessive use of analgesics, showed no differences between patients receiving 10 mg of flunarizine vs. TPM 50 mg during an observation period of eight weeks (-4.9 ± 3.8 vs. -2.3 ± 3.5; difference -2.6, 95%; CI -4.5 to -0.6; p=0.012), respectively. The safety and tolerability profile did not show statistically significant differences between the two groups (44). An open study in 40 patients also showed no statistically significant differences at the fourth month of observation but showed a reduction in days of severe pain by 75% for TPM vs. 70% for flunarizine (p=0.6236), in doses of TPM 100 mg vs. 5 mg 45.

Divalproex sodium: the comparison of ONABOT A 100 Ul vs. divalproex sodium 500 mg/day in a double dummy design with 59 patients with evaluations at months 1, 3, 6, and 9. In the analysis of the chronic migraine subgroup, no statistically significant intergroup differences were observed in the reduction of the number of migraine days, 50% efficacy rate and disability indices 46.

Naratriptan: in an observational study in patients with refractory chronic migraine with a dose of 2.5 mg twice a day, a reduction in headache frequency was reported after two-month treatment (15.3 days vs. 24.1 days on baseline, p<0.001), six months (9.1 days vs. 24.1, p<0.001), and after one year (7.3 days vs. 24.1, p<0.001) 47.

In a similar study, statistically significant reduction to one month (20.4, p<0.001), two months (18.9, p<0.001), and three months (19.0, p<0.001), with better HIT 6 score in every aspect (p<0.05 in all cases) was demonstrated 27.1 days/month after baseline by ITT analysis 48.

Clinical considerations

The data obtained for amitriptyline, flunarizine, and naratriptan are based on open studies, a consideration that limits the probability of generating evidence-based recommendations; however, obtaining therapeutic alternatives prior to the indication of high-cost medications establishes an option of interest in daily clinical practice. Despite the methodological limitations of the observational studies, amitriptyline, flunarizine, and divalproex sodium- valproic acid have similar degrees of efficacy to botulinum toxin A and topiramate; however, the presence of side effects that must be adjusted to the profile of each patient should be considered in order to maintain therapeutic adherence. The indication of naratriptan should only be considered in highly refractory patients. Blood pressure monitoring and informed consent are recommended in all cases and should not be indicated in patients with uncontrolled cardiovascular risk factors.

Final recommendation: amitriptyline, divalproex sodium, and flunarizine are recommended as part of the first-line therapeutic options in chronic migraine or as part of polytherapy. Naratriptan on a daily basis may be a treatment option in highly refractory patients. Consensus.

5. Is prednisolone effective in transitional therapy in chronic migraine and excessive use of analgesics?

PICO

Population: patients with chronic migraine and excessive use of analgesics

Intervention: prednisolone

Comparison: placebo - celecoxib - naratriptan

Outcome: percentage of patients requiring rescue analgesics, percentage of patients with moderate and severe pain hours.

Evidence analysis

Prednisolone. The comparison of prednisolone 100 mg vs. placebo in 20 patients showed significant reduction in headache hours of moderate or severe intensity in the first 72 hours after the withdrawal of analgesics (18.1 vs. 36.7 h, p=0.031, and 27.22 vs. 42.67 h, p= 0.05) 49. A second randomized, double-blind study carried out in 100 patients used a 60 mg dose of prednisolone, with progressive reduction to day 5, compared with placebo, and calculated the average days of headache, including frequency and intensity. The primary outcomes for each group did not show statistically significant differences (1.48 [CI 1.281.68] vs. 1.61 [CI 1.41-1.82]) 50. In a similar analysis, the comparison of 100 mg of prednisolone for five days showed statistically significant differences in the rate of analgesic consumption compared to placebo. This analysis found no differences in the reduction of hours with moderate and high intensity headache attacks 51. Comparison between prednisolone 75 mg with celecoxib 400 mg found reduction in pain intensity favoring celecoxib (p<0.001). This same study did not show differences in the reduction in headache frequency and consumption of analgesics (p=0.115, p=0.175, respectively) 52 (table 3).

Clinical considerations

The pooled analysis comparing prednisolone, celecoxib and placebo does not allow to establish differences about the ratio of hours with moderate and severe headache, and consumption of analgesics. There was a significant difference regarding pain intensity, which favors celecoxib. Although the studies coincide with the time of observation, randomization and similarity in the basic characteristics, there are differences in the outcome reports, loss to follow-up, and co-interventions. The mentioned factors indicate low quality evidence, an aspect that suggests the need for studies with a greater methodological scheme that allow exploring the usefulness of prednisolone, especially aimed at decreasing headache intensity and the need for analgesic consumption. The comparison in open design of prednisolone 60 mg vs. naratriptan showed statistically significant intragroup differences when compared to baseline, in headache frequency and intensity, rebound symptoms, and analgesic consumption (p<0.05 in all cases); however, this difference was not determined when performing the intergroup comparison 53 (table 3). There were also no differences found when comparing intra vs extra hospital treatments.

Final recommendation: prednisolone is not recommended for transitional therapy in patients with chronic migraine and with excessive use of analgesics. Evidence quality: moderate for headache rescue cases, low for mild or nonexistent headache days. Recommendation: weak.

CHRONIC TENSION-TYPE HEADACHE

6. What medications are effective and safe in the treatment of patients with chronic tension-type headache?

Amitriptyline

In a placebo-controlled clinical trial, slow-release amitriptyline 75 mg (25 mg the first week, 50 mg the second week, and 75 mg starting from the third week) significantly reduced the average daily duration of headache in patients with chronic tension-type headache between weeks 1 and 6; the effect of amitriptyline began to be significant at week 3 of treatment 55. In a controlled clinical trial with 60-90 mg amitriptylinoxide, 50-75 mg amitriptyline and placebo, no significant differences were found in the headache duration x frequency index or in the 50% reduction in headache intensity during 12 weeks of treatment 56. Amitriptyline was studied with citalopram in a 32-week placebo-controlled crossover clinical trial for chronic tension-type headache prophylaxis without depression. This medication reduced the area under the headache curve by 30%, compared to placebo, with a significant reduction in the frequency and duration of headache 57. In another controlled clinical trial of patients with chronic tension-type headache, 203 patients were assigned to amitriptyline 100 mg or nortriptyline 75 mg, placebo; stress management therapy and placebo; or stress management therapy and antidepressant. The three treatment groups improved, compared to placebo, but the improvement was faster with antidepressant medication than with stress management therapy with a response one month after treatment 58. In a meta-analysis with 387 patients, the amitriptyline group had 6.2 headache days less compared to placebo at week 4, the result was maintained at weeks 8, 12 and 24. Additionally, amitriptyline reduces the amount of analgesics and the headache index, in addition to improving the quality of life, with an evidence quality evaluated as high 59. The most frequent side effects of amitriptyline are dry mouth and drowsiness.

Venlafaxine

The efficacy and safety of venlafaxine was assessed in a controlled clinical trial in the treatment of chronic tension-type headache in patients without anxiety or depression 60. Thirty-four patients were treated daily with venlafaxine XR 150 mg, while 26 patients were provided with placebo for 12 weeks. Venlafaxine was taken once a day after breakfast; the first week they took 75 mg and then the dose was raised to 150 mg. The venlafaxine group showed a significant reduction in the number of headache days (from 14.9 to 11.7 days) compared to the placebo group, which did not decrease headache days (from 13.3 to 14.2). The number of responders (a 50% or more reduction in the headache days) was significantly higher in the venlafaxine group (44%) than in the placebo group (15%); NNT was 3.48. In the venlafaxine group, six patients discontinued treatment due to adverse effects (vomiting, epigastralgia, nausea, loss of libido/anorgasmia) and none of the patients were reported to withdraw in the placebo group. The NNH for a side effect was 5.58.

Imipramine

In a controlled clinical trial, the efficacy of imipramine 25 mg was evaluated every 12 hours in patients with chronic tension-type headache, compared to transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation. Imipramine significantly reduces headache intensity, with a score of 6.71 to 2.49 on the visual analog scale, with a significantly better reduction compared to transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation 61.

The efficacy of mirtazapine in chronic tension-type headache was evaluated in a controlled crossover clinical trial 62. Mirtazapine 15 to 30 mg or placebo was administered, two to three hours before bedtime for eight weeks separated by a two-week wash period. The area under the headache curve (duration x intensity) was 34% lower during treatment with mirtazapine than with placebo in 22 patients who participated for the whole study. During the last four weeks of treatment with mirtazapine, 45% of patients improved the area under the curve by at least 30% compared to placebo. The number of headache days in the four weeks decreased from 28 during the placebo period to 25.5 during the period with mirtazapine. Two patients withdrew during active treatment due to the effects.

Clinical considerations

Despite its high prevalence, there are no clinical trials with a solid methodology to confirm the efficacy of the available medications. In all cases, the diagnosis of chronic migraine with intensity pattern modification should be ruled out before considering chronic tension-type headache. It is recommended to start with the lowest possible dose and raise in accordance with efficacy and tolerability. It is necessary to take into account the profile of cholinergic side effects that significantly limit adherence to treatment.

Final recommendation: amitriptyline, mirtazapine, venlafaxine and imipramine are recommended therapeutic options for the treatment of chronic tension-type headache. Consensus.

HEMICRANIA CONTINUA

7. What medications are indicated for the treatment of patients with hemicrania continua?

Indomethacin

Indomethacin has proven to be an effective medication in the acute and preventive treatment of hemicrania continua, even since the initial reports 63,64. This efficacy has been demonstrated with doses between 25-150 mg/day with total symptom control after 72 hours of treatment initiation 65,66.

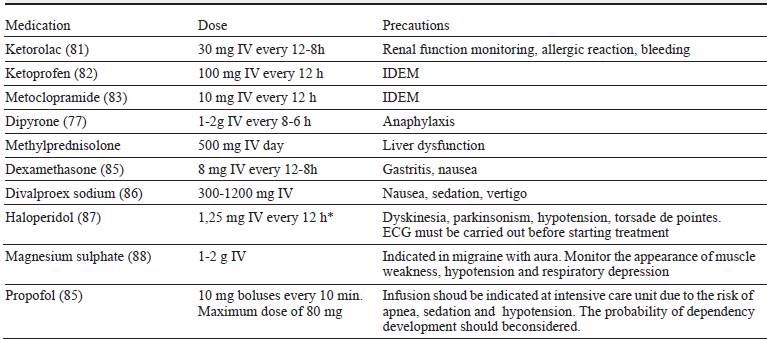

Table 5 Pharmacological options in the hospital treatment of patients with refractory chronic migraine.

* The recommended dose is lower than that used in clinical trials, in order to reduce the likelihood of side effects.

Source: authors.

In a cohort of 36 patients, 33 with criteria for HC who received placebo and indomethacin at different times achieved total pain control in 89% of the cases when they were exposed to the medication (average dose 176 mg/ day, with a minimum of 25 and maximum of 500 mg/ day). None of the patients in the placebo group achieved improvement 67. Another series of 36 patients exposed to oral indomethacin test with a maximum dose of 250 mg/day reported pain control in all patients; however, poor tolerance to high doses of the molecule was described 68. In a retrospective case series, three out of ten patients diagnosed with hemicrania continua reported efficacy in doses of 50-300 mg with limited gastrointestinal tolerability in all cases 69.

In a series of 26 patients with an average dose of 75 mg, 16 with a diagnosis of hemicrania continua, 3.8 years were followed up, and improvement was reported within the first three days of treatment. During follow-up, 42% of patients maintained clinical control, which allowed the dose to be reduced up to 60% 66.

Melatonin

In 2006, the case of a 42-year-old patient was reported, with HC and indomethacin intolerance (but with complete response to it), who achieved total pain control with the use of 7 mg of melatonin during the 5-month-follow-up time 70. Subsequently, three women with indomethacin intolerance used melatonin in ascending dose every fifth day, starting with 3 mg to achieve total pain control (maximum allowed 24 mg/day), two of them at 9 mg and the third at 15 mg reported total pain control; in cases of pain attack, control was reported with 6 mg rescue dose 71.

In 2013, the case of a 60-year-old patient with a response to indomethacin was reported, but with limited tolerability, in which the administration of melatonin 9 mg/day produced complete pain control 72. The largest case series presented the retrospective analysis of 11 patients (nine women, two men). Of these, six showed no response to the use of melatonin in doses of 9-27 mg/ day, two achieved total pain control at low doses of 3-6 mg/day, while the remaining three obtained only partial control, which allowed the decrease of the daily dose of this medicine 73.

Topiramate

In 2006, two cases were reported with hemicrania continua and a positive response to indomethacin, but with adhe- rence limitations due to non-tolerability. Both patients, who received topiramate between 100 and 200 mg/day, being intolerant as well though, achieved pain control similar to that obtained with indomethacin 74. Afterwards, based on the previous reference, two similar cases were reported with indomethacin intolerance due to gastrointestinal effects. After the start of topiramate at 150-200 mg/day, sustained pain control was achieved after six and eight months of treatment suspension 75. Recently, pain control was reported in two patients, combining indomethacin 75 mg/day and topiramate 50 to 75 mg/day, given the non-tolerance at higher doses in one or both molecules, which shows synergy between them and total pain control 76.

Celecoxib

In a series of 14 patients, nine with rofecoxib and five with celecoxib, the latter group, in weekly ascending dose up to a maximum of 800 mg/day, produced total or partial response in 80% of cases 77. In a report of four patients with hemicrania continua and indomethacin intolerance, total pain control was documented in doses ranging from 200-400 mg/day and with persistence of the clinical effect to the continuous use of the molecule in a range of 6 to 18 months later 78.

Clinical considerations

Indomethacin, in doses of 25 up to 250 mg per day, is considered the medication of choice; its efficacy is diagnostic criteria in HC 4. However, there are cases in which there is no efficacy, or this is limited to aspects of tolerability and safety. In this type of cases it is possible to consider the use of melatonin 3-30 mg/day, topiramate 75-200 mg/day or celecoxib 200-400 mg/day in joint or replacement therapy. Prior to this consideration, the addition of sodium, potassium or misoprostol-type prostaglan-din pump inhibitors may improve indomethacin tolerance. The cardiovascular risk profile associated with celecoxib should be considered.

Final recommendation: indomethacin is the medication of choice for patients with hemicrania continua. In cases of non-efficacy or non-tolerability, the use of melatonin, celecoxib or topiramate is recommended in addition or replacement therapy. Consensus

NEW DAILY PERSISTENT HEADACHE

8. What pharmacological options can be effective in the treatment of patients with new daily persistent headache?

Gabapentin

Gabapentin, in doses of 1800 and 2700 mg per day has reported efficacy in series of patients with new daily persistent headache 79,80; the main adverse effects include sedation, ataxia and fatigue.

Doxycycline

In an open study that included four patients with new daily persistent headache and elevated tumor necrosis factor in the open CSF, doxycycline was used at a dose of 100 mg every 12 hours for three months; at two months of treatment, partial or total improvement was reported; the main adverse effects were nausea, vomiting and epigastralgia 80.

Clinical considerations

The low prevalence of new daily persistent headache makes it difficult to obtain information based on studies that provide evidence for the treatment of this medical condition. The therapeutic response is limited and, probably, the resolution of symptoms is explained by the disease's own remission, rather than the effect provided by the pharmacological agents. Two disease phenotypes have been described, one similar to migraine and the second to tension-type headache. According to each of them it is possible to choose approved pharmacological options for each of these entities.

Final recommendation: despite the limited evidence, the use of gabapentin and/or doxycycline is recommended as treatment options for new daily persistent headache. Consensus.

COMPLEMENTARY INTERVENTIONS

9. "When should hospitalization be considered in patients with chronic migraine?

Clinical considerations

It is recommended in patients without response to outpatient treatment despite optimal doses of acute and preventive medications, presence of comorbidities that limit adherence to therapeutic indications and excessive use of opioids. This procedure is justified by the use of parenteral medications and comprehensive assessment including psychiatry, neuropsychology, nutrition and other specialties considered according to the basic profile of each patient 11. The recommended options in hospital treatment vary according to the comorbidities of each patient and the options available in each institution (table 4).

10. What procedures are indicated in the treatment of patients with chronic daily headache?

Nerve blocks

CDH is included as one of the indications for the pericranial nerve blockade 89. In chronic migraine, efficacy has been described in a study of 36 patients who compared bupivacaine infiltrations of the occipital nerve vs placebo. This study showed a significant reduction in the frequency, intensity and duration of headache episodes compared to baseline and placebo 90. A second study, with 44 patients, showed similar results also comparing placebo vs. bupivacaine 91. According to observations in real clinical practice, the efficacy of this type of intervention starts minutes after infiltration 92.

The sphenopalatine ganglion block has also shown a significant reduction in the numerical pain scale compared to placebo in patients with chronic migraine in measurements at 15, 30 minutes and 24 hours, after irrigation of the ganglion with bupivacaine. This difference between placebo and treatment was not reached after months 1 and 6, despite the difference in the numerical scale compared to the baseline 93. In a series of cases with hemicrania continua composed of 36 patients (28 women, 8 men), 13 were operated for non-tolerance to indomethacin with block 1:1 mixture of bupivacaine/mepivacaine. Of this group, 7/13 obtained total pain control, 5/13 got a decrease of three points in pain scale, and one had no response; the therapeutic effect lasted an average of three months 68.

In a prospective series of 22 patients with hemicrania continua, nine cases of indomethacin intolerance were intervened with greater occipital and supraorbital nerve blockade, with 1:1 mixture of bupivacaine/mepivacaine; in the cases of trochlear block 4 mg of triamcinolone were injected. Regarding the presence of pain in the point exploration, 5/9 patients obtained total pain control and 4/5 partial control. The duration of the most frequent analgesic effect was three months 94. Sphenopalatine ganglion block was reported effective in a patient with hemicrania continua, intolerant to indo- methacin, topiramate and no response to melatonin. After ipsilateral irrigations with bupivacaine 0.5%, twice a week for 6 weeks, through Tx360® and injecting from week 6, total pain control was achieved, and subsequently control blockades were made every four to five weeks 95.

Several retrospective case series with a small number of patients with new daily persistent headache (3-23 patients, 57 patients in total) were treated with bupivacaine and methylprednisolone, or lidocaine and methylprednisolone blockade, in different nerves, and it was the greater occipital nerve the most frequently operated. These reports described a response rate of 33.3 to 66% with a response duration of one day to 5.4 weeks 73,89-92.

Clinical considerations

Nerve blocks seek to control the phenomenon of peri-cranial hypersensitivity common to several subtypes of headaches, including those of the primary type, and the entities that make up the CDH. Although most of the reports are described with bupivacaine, it is possible to use lidocaine in equivalent doses to 1-2 ml per point in the occipital region and 0.1-0.3 ml in the temporal region and facial points. Its use is safe in pregnant women and a short-term clinical effect is expected, which can be useful in the transition of the effect of the chosen preventive medications and in the detoxification due to excessive use of analgesics.

CONCLUSION

The recommendations generated for the preventive treatment of chronic migraine, chronic tension-type headache, hemicrania continua, and new daily persistent headache coincide with the concepts contained in similar documents published by other scientific societies, with modifications adjusted to the population 32.

Regarding the limited availability of evidence in most of the recommended molecules, the consensus methodology complements the information obtained through systematic review and Grade methodology.

This strategy increases treatment alternatives prior to indication of high-cost therapies, which allows economic factors to be considered alongside clinical decisions. This document must be modified within five years, based on the guidelines of the ACN headache group and the need for incorporation of new sources of scientific evidence.

texto en

texto en