Introduction

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES), or reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome (RPLS), represents a clinical and radiological condition with diverse underlying causes, all characterized by shared neuroimaging features. The syndrome was first introduced in 1996 by Hinchey et al. 1. Although, the precise global incidence of PRES is unknown, it notably tends to manifest during pregnancy, especially among patients who develop pre-eclampsia/eclampsia, those experiencing acute elevation in blood pressure, or undergo immunosuppressive therapy 2-3. Psychiatric manifestations related to PRES are poorly described in the medical literature; they are atypical, with few case reports during and after the illness. Documented symptoms are diverse, ranging from confusion, agitation, and even hallucinations 4.

Here, we present the case of a 29-year-old woman who experienced cardiac arrest, requiring 25 minutes of advanced cardiac life support. After 15 days, she experienced depressive symptoms, hallucinations, seizures, and hypertension. A brain-computer tomography (CT) scan findings of parieto-occipital vasogenic edema suggested the diagnosis of PRES.

Case report

A 29-year-old woman, in her first pregnancy at 9.6 weeks gestation, was admitted with a chief complaint of widespread abdominal pain that had persisted for the past 20 hours. The patient had no prior medical or personal psychiatric history, with a family history of her mother attempting suicide.

Upon admission, her vital signs were as follows: hypotension (69/43 mmHg), tachycardia (120 beats per minute), delayed capillary refill (4 seconds), and signs of peritoneal irritation. Notably, her mental state remained unchanged at this stage. Shortly after admission, the patient experienced cardiac arrest, requiring immediate cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) for 25 minutes. Imaging studies, including abdominal ultrasound and transvaginal obstetric ultrasonography, indicated a likely ruptured ectopic pregnancy. Paraclinical assessments revealed severe anemia (hemoglobin: 4.8 g/dl), consumption coagulopathy, elevated lactic acid levels (12.34 mmol/l), metabolic acidosis, and elevated creatinine (2.82 mg/dl). Subsequently, the patient underwent an exploratory laparotomy, during which 3500 ml of he-moperitoneum was drained, and a left salpingectomy was performed.

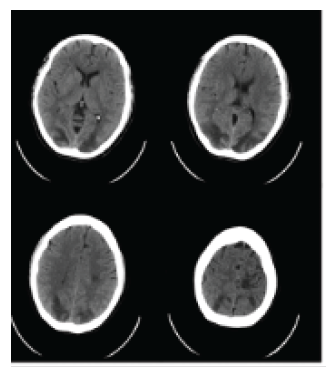

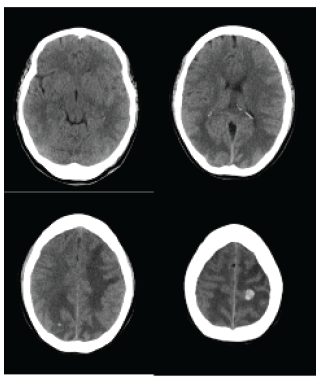

She was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), where she required mechanical ventilation care and hemodialysis after acute kidney injury. After a two-week ICU stay, she was transferred to the general wards. In the last week, she has been experiencing loss of appetite, sadness, irritability, anhedonia, hopelessness, expressing thoughts like 'I'm not going to recover,' insomnia, feelings of worthlessness, death thoughts without any suicidal intentions or plans, and poor introspection. Additionally, she presented complex visual hallucinations described as 'a black male who visits me every night and puts himself on top of the bed,' causing her to feel fear. No other abnormalities were noted on the mental examination. Psychiatry initiated treatment with olanzapine. Later, she experienced a 50-second episode of generalized tonic-clonic seizure followed by a 1-minute postictal state, and two hours later, another epileptic crisis occurred; the CT scan (figure 1) showed parieto-occipital vasogenic edema. The next day, she developed a severe holocranial headache with blurred vision; during the physical examination, a hypertension crisis (186/121 mmHg) was found, fundus examination was regular as well as cranial nerves, but there was brachiocrural hemiparesis (0/5), hypoesthesia, augmented reflexes (+++/++++) and a left foot extensor plantar response. A new CT scan (figure 2) showed subarachnoid hemorrhage, intracranial hemorrhage, and vasogenic edema that may be associated with posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. The hospital did not count on access to magnetic resonance, so it was not performed. Infections and other autoimmune diseases were ruled out as differential diagnoses.

Parietooccipital vasogenic edema, potentially related to reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome

Source: Image provided by authors.

Figure 1 Initial axial brain CT scan

Subarachnoid hemorrhage observed in the left frontal convexity, accompanied by intraparenchymal hemorrhagic foci. Vasogenic edema, potentially related to posterior reversible leukoencephalopathy syndrome

Source: Image provided by authors.

Figure 2 Subsequent axial brain CT scan

After admission to the ICU, a pan-angiography revealed normal blood vessels, neurocritical goals were met, hypertension was successfully treated, and there were no new epileptic crises.

After one week, hemodialysis was discontinued, and without needing any additional intervention, she was again transferred to general hospitalization wards. Following her neurological condition's improvement, forty days after her admission, she was discharged with complete resolution of her neurological state.

Discussion

A case of PRES in a patient with obstetric complications who developed neuropsychiatric manifestations is presented. We will discuss the neuropsychiatric manifestations of PRES and the relevance of this case in shedding light on the significance of these symptoms. PRES is conventionally defined as a clinical and imaging syndrome marked by symptoms such as headaches, encephalopathy, visual disturbances, and seizures 1. Nevertheless, one of the most critical features of this disorder is the potential for symptom reversibility. Moreover, psychiatric co-morbidity is less frequently reported. Among the numerous potential causes of PRES, preeclampsia, and eclampsia are commonly identified as the primary triggers 5. Hence, seizures, vision loss, depressive symptoms, and suicide ideas in a full-term primigravida can yield a complex scenario with multiple potential explanations.

A retrospective case series of 47 patients over nine years in England revealed that psychiatric symptoms were reported in 26% of PRES cases. Interestingly, these symptoms could manifest before, during, or after the onset of PRES 4. The most frequently observed clinical features included speech disturbance, confusion, agitation, hallucinations, disinhibition, low mood, delusions, vivid dreams, religious preoccupations, self-harm tendencies, and anxiety 4. Precisely, this patient experienced depressive symptoms and visual hallucinations in the days leading up to the first seizure episode. A literature review of case reports summarizing psychiatric symptoms is presented in table 1. Of these, it must be remarked that the most common symptoms were catatonia, agitation, memory impairment, and psychosis. Moreover, 75% of these cases were females, and half of the patients required antipsychotics or benzodiazepines for symptom relief 6-13. It is worth noting that there is a scarcity of studies that specifically address the psychiatric aspects of PRES morbidity, which is noteworthy as it leaves a gap in our understanding of how psychiatric symptoms may manifest in patients with PRES and what implications this may have for their clinical management and long-term outcomes.

Table 1 Comparative overview of psychiatric symptoms in PRES case reports

| Author, year and country | Sex and age (years) | History of psychiatric disease | History of organic disease | Neuropsy-chiatric manifestation of PRES | Psychopharmacology drug use | Vital state (Alive or death) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gómez S et al., 2024, Colombia (this case) | Female, 29 years old | Family history | No | Irritability, anhedonia, insomnia, worthlessness ideas, death thoughts complex visual hallucinations | Olanzapine | Alive |

| Andelo J et al., 2016, Croatia 6 | Female. 26 years old | Non reported | Non reported | Short- and long-term amnesia | Non reported | Alive |

| Spiegel D et al., 2011, United States 7 | Female, 48 years old | Non reported | Arterial hypertension and cerebrovascular disease | Catatonia, grimacing, stereotypy, visual hallucinations, blunted affect | Olanzapine | Alive |

| Sarala Kumari D et al., 2020, India 8 | Female, 20 years old | Non reported | Porphyria | Irritability, agitation, psychosis | Clonazepam | Alive |

| Fernández-Sotos P et al., 2019, Spain 9 | Male, 75 years old | Non reported | Parkinson disease, arterial hypertension, kidney transplantation | Delirium, expansive mood, confusion, visual hallucinations | Non reported | Alive |

| Shen FC et al., 2008, Taiwan 10 | Male, 60 years old | Non reported | Porphyria | Psychosis, disorientation | Non reported | Alive |

| Takaoka Y. et al., 2020, Japan 11 | Female, 26 years old | Schizophrenia | Non reported | Attention disorder, decreased visual memory, delusions, catatonia | Non reported | Alive |

| Tsai S et al., 2016, Australia 12 | Female, 57 years old | Non reported | Non reported | Delusional infestation | Aripiprazole | Alive |

| Klingensmith K et al., 2017, United States 13 | Female, 61 years old | Schizoaffecti-ve disorder | Non reported | Catatonia, auditory manifestations, acute-onset confusion | Lorazepam | Alive |

Source: Data generated by authors.

While no specific diagnostic criteria exist, PRES is increasingly recognized as a disorder. Even if it is not common, in the presentation of psychiatric symptoms, the clinician may promptly become suspicious and proceed with diagnostic assessments. In the appropriate clinical setting, neuroimaging is crucial for diagnosis. In bilateral cerebral regions supplied by the posterior circulation, edema is apparent in non-contrast computed tomography (CT) brain scans 1. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), when available, is preferred for its sensitivity to vasogenic edema through fluid-attenuated inversion recovery and T2-weighted sequences; it typically reveals signal changes in the bilateral white-matter regions, often within the occipital lobes 14. This patient's CT neuroimaging revealed bilateral symmetrical hypo-densities in the white matter of the parieto-occipital areas. The characteristic involvement of the occipital and posterior parietal lobes, which is a defining feature of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES), may be attributed to lower sympathetic innervation in these posterior cerebral regions, compared to the anterior circulation 15. This lower sympathetic innervation renders these areas more susceptible to injury during blood pressure fluctuations 16-17.

An association can be established between neuropsychiatry symptoms and the temporal-limbic network lesions commonly found in PRES 18-19. Neuropsychiatric symptoms often stem from disruptions in specific limbic networks, widely distributed throughout the brain 17. Despite their diffuse nature, these symptoms remain recognizable as manifestations of temporolimbic lesions, albeit lacking neuroanatomical specificity 19. There is an association between hippocampal sclerosis and psychosis in epilepsy that has been well-documented 20.

Additionally, individuals with schizophrenia often display changes in the hippocampi, including gray matter loss, reduced glutamate and disarray of hippocampal cells 21. Moreover, delusions, emotional behaviors, and other neuropsychiatric symptoms may occasionally be secondary to PRES, due to the middle and posterior cerebral arteries supplying regions of the temporal lobe 17. Despite its label as "reversible," PRES can lead to residual infarcts and subsequent leukomalacia affecting areas of the mesolimbic system, potentially resulting in possible sequelae of neuropsychiatric symptoms 18.

Although PRES is generally considered a reversible condition, it is essential to acknowledge that residual infarcts and leukomalacia can occur as potential consequences, which may align with the possibility of long-term psychiatric symptoms in some patients 4. PRES typically leads to favorable outcomes when managed appropriately, with patients often recovering from neurological deficits within a consistently observed two-week timeframe in subsequent studies 15. The recovery of the presented case aligns with these findings, as the gradual reduction of blood pressure often results in a marked improvement in patients' conditions 22. She also had improvement in psychomotor agitation, and the hallucinations ceased. Nevertheless, it is crucial to recognize that it may lead to residual brain damage, which may be associated with the development of permanent severe neurological impairments and long-term psychiatric symptoms.

Future research and case series on PRES should aim to comprehensively document psychiatric comorbidity, including the period preceding the condition's onset. This approach will help clarify the true significance of these findings and their connection with the neuropsychiatric trajectory of such illnesses.

Conclusions

This case sheds light on the importance of recognizing psychiatric symptoms as a manifestation of PRES, which should not be underestimated. While they are not clearly understood, there are apparent anatomical relationships between PRES pathogenesis and limbic circuits. Consider this possibility as a diagnosis in the appropriate clinical scenario when evaluating psychiatric symptoms. Further investigations could expand our understanding of the neurobiology of this correlation and the short- and long-term clinical outcomes that a neuropsychiatric presentation in PRES could generate in patients.