Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Revista colombiana de Gastroenterología

versão impressa ISSN 0120-9957versão On-line ISSN 2500-7440

Rev Col Gastroenterol v.27 n.1 Bogotá jan./mar. 2012

Risk factors for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) associated with pancreatitis and hyperamylasemia

Martín Alonso Gómez Zuleta, MD, (1) Lindsay Delgado, MD, (2) Víctor Arbeláez, MD. (3)

(1) Gastroenterologist, Professor in the Gastroenterology Unit of the Internal Medicine Faculty at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia and at the Hospital El Tunal in Bogotá, Colombia

(2) Gastroenterologist at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia and at the Hospital de la Policía in Bogotá, Colombia

(3) Gastroenterologist at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia and at the Centro de Enfermedades Digestivas in Bogotá, Colombia

Presented at the "Congreso Colombiano de Enfermedades Digestivas - ACADI", Medellín december 7 to 8 of 2011

Received: 02-02-12 Accepted: 28-02-12

Abstract

Although both asymptomatic hyperamylasemia and pancreatitis are clinical situations associated with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), asymptomatic hyperamylasemia is a very serious entity while asymptomatic pancreatitis has minimal significance. Risks for patients following ERCP have been described in various publications, but the behavior of these factors varies from one population to another. For this reason it has become important to study these factors in our own environment to identify which patients have higher probabilities of pancreatitis and/or hyperamylasemia following ERCP so that we can make clinically applicable recommendations.

Materials and methods. This is a cross sectional, analytical, prospective and observational study of patients who underwent ERCP at the Hospital El Tunal. Before undergoing ERCP all patients filed out a form about their most important epidemiological variables, laboratory study results and imaging study results. After undergoing the procedure they remained in the hospital for at least 24 hours during which time amylase levels, pain, and other complications were monitored and evaluated.

Results. 152 patients met the study's inclusion requirements. All underwent ERCP because of cholestasis and dilation of the extrahepatic bile duct. 94 of these patients (61.8%) were women. Patients average age was 60.07 ± 15.9 years. The incidence of hyperamylasemia was 65.8 % (n=100), but only nine of these cases were accompanied by the abdominal pain typical of hyperamylasemia after the first 24 hours following the procedure. In other words, the incidence of pancreatitis following ERCP was 5.9% (n=9) while the incidence of asymptomatic hyperamylasemia was 59.8% (91 patients). Four risk factors for pancreatitis were identified: multiple attempts at biliary cannulation (OR 23.6), precut papillotomy (OR 6.0), use of contrast media in biliary duct radiography (OR 4.65), and placement of a biliary stent (OR 5.19).

Conclusion. Our work demonstrates that pancreatitis following ERCP is a very common complication, but that asymptomatic hyperamylasemia is even more common. Even though the latter does not have any implications for the patient, it does have implications for clinical practice. Our current recommendation for monitoring a patient following an ERCP is that no testing for amylases needs to be done if that patient has no abdominal pain since 60% of these cases will have elevated levels of amylase which could generate confusion. Of the four risk factors which were identified which might potentially be modified, the most important is that the ERCP should be performed by a well trained professional.

Key words

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), complications, pancreatitis, hyperamylasemia.

Even though pancreatitis and asymptomatic hyperamylasemia are clinical conditions which are frequently associated with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), pancreatitis is serious, while asymptomatic hyperamylasemia has minimum clinical significance. Its reported incidence is about 50% that of pancreatitis, but it has been studied much less as a result (1-3).

Pancreatitis is the most common complication caused by ERCP: its reported incidence ranges from 1.8% to 7.2% in most prospective series (1-4). The criteria accepted for its diagnosis since 1991 and include pancreatic type abdominal pain associated with amylase levels least 3 times their reference values. Both must occur within 24 hours of ERCP. Pain and symptoms need to be sufficiently severe to require prolongation of hospitalization or hospital readmission (1, 3, 5).

Even though 80% of post ERCP pancreatitis episodes are mild, a number of patients develop severe pancreatitis and require prolonged hospitalization, including admission to intensive care units, and require greater hospital resources (1, 5). Pancreatitis may even be fatal. Despite recent improvements in techniques and increased expertise among endoscopists, the incidence of pancreatitis has not decreased significantly. Eff orts still aim at diminishing the incidence and severity of pancreatitis (1, 3, 6).

Prospective studies of large numbers of patients using univariate and multivariate analysis have identified several specific risk factors related to both the patient and the procedure (6-9). Several factors may be responsible for the pathogenesis of hyperamylasemia and post ERCP pancreatitis. In both cases factors may act independently or together. Some technical factors include injection of contrast medium into the main pancreatic duct (duct of Wirsung), especially when bile duct cannulation is difficult, the pressure and speed with of injection of the dye, trauma due to the sphincterotomy and the type of current used (1, 3, 7). Other risk related to the patient include the presence and number of calculi found in the bile duct, female gender, age of less than 50 years, and previous history of pancreatitis (1, 2, 8).

On the other hand, the percentage of patients who experience hyperamylasemia following ERCP is still not known by our profession. Hyperamylasemia does not necessarily mean pancreatitis is present because most of the time there is no pain. Nevertheless, because of ignorance in clinical practice hyperamylasemia is always considered to be pancreatitis. This not only delays proper management such as hospital discharge or performance of a cholecystectomy, it also overlooks legal implications such as the possibility of lawsuits.

Even though risk factors for pancreatitis following ERCP are described in various publications (1, 2, 5, 9), its behavior varies from one population to another. Consequently, its study in our environment is important so that we can identify those patients with a greater probability of presenting post ERCP pancreatitis and/ or hyperamylasemia and make clinical applicable recommendations.

GENERAL OBJECTIVES

Describe risk factors associated with pancreatitis and/ or asymptomatic hyperamylasemia in patients who underwent ERCP in the Hospital El Tunal in Bogotá, Colombia.

SPECIFIC OBJECTIVES

- Establish the incidence of asymptomatic hyperamylasemia in patients who received an ERCP.

- Establish the incidence of pancreatitis following ERCPs in the gastroenterology service at Hospital El Tunal.

- Determine if there are any differences in clinical manifestations related to the occurrence of asymptomatic hyperamylasemia and pancreatitis following ERCPs.

- Determine if there are any differences in the patients' characteristics (age, sex, etc.) and the occurrence of hyperamylasemia and pancreatitis following ERCPs.

- Establish if there is any relation between procedural techniques and the occurrence of hyperamylasemia and pancreatitis following ERCPs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Type of study

Prospective, observational and analytical cross section study.

Population and sample

The sample population was made up of adult patients who had been undergone ERCPs in the Gastroenterology Unit of the Hospital El Tunal in Bogota between January 2009 and August 2011.

Inclusion criteria

- Patients over 18 years old

- Patients with cholestasis and dilated extra hepatic bile ducts

- Patients with a high risk of choledocholithiasis.

- Patients with choledocholithiasis diagnosed through endoscopic ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging.

Exclusion criteria

- Patients with decompensated cardiopulmonary disease

- Patients with coagulopathies

- Patients with acute pancreatitis prior to ERCP

- Patients with bile duct lesions.

- Patients with a low or intermediate risk of choledocholithiasis.

Data collection technique

The primary source of data collection was direct patient observation while patients' clinical charts were used as secondary sources. The primary investigator was responsible for completion of Data Collection Forms using these sources. Table 1 shows the used variables.

Each patient selected signed a consent form in order to participate in the study. Patients underwent ERCPs, were interviewed, and had Data Collection Forms filled out.

All patients underwent ERCPs in radiology room under sedation administered by an anesthesiologist. One to two 2 mg/kg propofol boluses were administered in addition to continuous infusion of 4-6 mg/kg/h. Heart rate and frequency, oxygen saturation and arterial tension were monitored during the procedure. Olympus 150 series diagnostic and therapeutic duodenoscopes were used. Specific techniques used during ERCP included cannulation of Vater's Papilla, sphincterotomy, dilation, and stent insertion (5-9).

Following ERCPs patients were taken to a recovery room where they were constantly monitored. All patients were hospitalized for 24 hours after the procedure as part of the study's protocol. 24 hours after ERCPs amylase levels were checked and whether or not patients had it acute post procedure pancreatitis was determined. This diagnosis was established when pancreatic type abdominal pain (epigastric pain radiating to the back) was present and accompanied by an amylase level 3 times or more the normal limit. The diagnosis was not established if the patient was suffering colic type pain or pain in the right hypochondrium which suggests the persistence of stones.

Once the data collection was completed data was entered into the computer data base which was then reviewed and debugged in order to identify and correct any inconsistencies between the database and the clinical charts.

ANALYSIS PLAN

Descriptive statistics

Initial descriptive statistical analysis of variables included measurement of central tendencies and dispersions. Quantitative variables were then described with averages and standard deviations and qualitative variables with absolute frequencies and percentages. The incidences of asymptomatic hyperamylasemia and post ERCP pancreatitis were calculated through this analysis.

Bivariate analysis

Bivariate analysis was used to identify diff erences between the average amylase levels of the group with asymptomatic hyperamylasemia and the group with pancreatitis. Chi squared analysis was used to evaluate whether there were relations between patient factors such as technique and occurrence of pancreatitis following ERCP.

Ethical considerations

This study's protocol was elaborated using all the recommendations for human research contained in the Helsinki Declaration and Resolution 8430 of 1993 of the Colombian Ministry of Health. According to that resolution this research is considered to be a risk free investigation because there was no intervention or intentional modification of the variables under observation among the participants.

Among the most highly regarded ethical principles taken into account were confidentiality and safeguarding of professional secrecy.

Informed consent forms were signed for conducting ERCPs in all cases included in the study. Consent was preceded by a complete and clear explanation of the research objectives, and possible risks and benefits of the study.

RESULTS

A total of 152 patients who were suitable for ERCP because they presented cholestasis and dilation of the extra hepatic bile duct met the inclusion criteria. 61.8% of the patients were women (n=94). Th e average age was 60.07 ± 15.9 years old.

The incidence of hyperamylasemia in the study population was 6.8% (n=100), but only 9 of these cases had typical abdominal pain more than 24 hours after the exam hence incidence pancreatitis following ERCP in this study was 5.9% (n=9). 59.8% (91) of the patients had hyperamylasemia with no abdominal pain (asymptomatic).

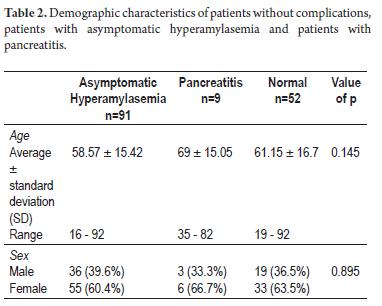

Demographic characteristics

Even though the average age was greater among the patients with pancreatitis, there were no significant diff erences among the groups of patients. The three groups had a greater percentage of female patients without any important differences (table 2).

Clinical characteristics

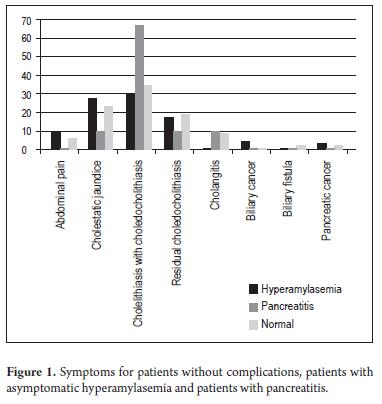

Cholelithiasis with suspected choledocholithiasis was the most frequently observed indication in all groups, although the percentage among patients with pancreatitis (66.7%) was much higher than that among patients with asymptomatic hyperamylasemia (30.8%). Cholestatic jaundice and residual choledocholithiasis occupied second place. None of the observed diff erences wwere statistically signifi cant (p > 0, 05) (Table 3, Figure 1).

All of the patients with pancreatitis and more than 90% of those who ended with asymptomatic hyperamylasemia had colicky abdominal pain prior to ERCP. Jaundice prior to ERCP was present in a slightly greater percentage of cases with asymptomatic hyperamylasemia while fever was present in a greater number of cases with pancreatitis. No statistically significant differences regarding the behavior of these manifestations were found in either group (table 3).

Clinical characteristics

Patients with pancreatitis had higher average levels of alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase (Table 4) than did other patients. On the other hand, the patients with asymptomatic hyperamylasemia showed higher average levels of alkaline phosphatase. Patients with neither entity showed higher average levels of total and direct bilirubin. No statistically significant diff erences were observed in any of these cases (p>0.05) (Table 4).

There were no important differences in percentages of patients with abnormal direct and total bilirubin among the 3 groups (p=0.968): Abnormal direct bilirubin was found in 76.9% of patients with hyperamylasemia, 77.8% and of those with pancreatitis, and 78.8% of those without any complications. Abnormal total bilirubin was found in 72.5% of patients with hyperamylasemia, 77.7% of those with pancreatitis and 73.1% of those without complications.

Transminase levels were abnormal in more than 60% of all patients. Although the percentage was slightly higher among those with pancreatitis, it was not statistically significant.

ULTRASOUND FINDINGS

Among the patients with asymptomatic hyperamylasemia 37.5% had cholelithiasis while 25% had dilated extra hepatic bile ducts without stones. One third of the patients with pancreatitis (33.3%) had choledocholithiasis and another third had normal sonograms. Among the most frequent ultra-Among the patients with asymptomatic hyperamyla-sound findings were dilation of the extrahepatic bile duct semia 37.5% had cholelithiasis while 25% had dilated without stones (38.5%) and cholelithiasis (30.8%). None extra hepatic bile ducts without stones. One third of the of the observed differences were statistically significant patients with pancreatitis (33.3%) had choledocholithia-(p=0.080) (Table 5).

ENDOSCOPIC FINDINGS

During ERCPs patients with pancreatitis had larger choledocal diameters than did those with only asymptomatic hyperamylasemia. Those with neither entity showed no signifi cant differences. Even though the majority of patients in all three groups During ERCPs patients with pancreatitis had larger choledocal of patients had normal intrahepatic bile ducts, the most frediameters than did those with only asymptomatic hyperamy-quently observed alteration in all cases was dilation (Table 6).

The papilla was normal in 69.2% of the patients with pancreatitis, in 55.6% of the patients with hyperamylasemia and in 76.9% of the normal patients. Peridiverticular papillae were the most frequently observed alterations in all three groups (Table 6).

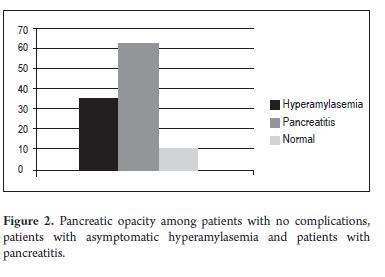

There were no differences in patient distributions in the three groups according to the number of calculi found. The calculi found also had similar average sizes in the three cases (Table 6). In contrast, pancreatic duct opacification was used significantly more frequently among patients with pancreatitis (Figure 2).

The most frequent diagnoses resulting from ERCPs were choledocholithiasis with dilated bile ducts and dilated extrahepatic bile ducts without stones. 42.9% the of patients with hyperamylasemia had choledocholithiasis with dilated bile ducts while 46.2% of the patients without complications had choledocholithiasis with dilated bile ducts. 15.4% of the patients with hyperamylasemia had dilated extrahepatic bile ducts without stones while 13.5% of the patients without complications had dilated extrahepatic bile ducts without stones. The percentages of patients with pancreatitis, Type 1 Klatskin Tumors and pancreatic cancer were 11.1% in each case. ERCP was considered to have failed for only 2 of the patients the patients without pancreatitis or hyperamylasemia. There were 25 patients with normal ERCPs most of whom were patients with asymptomatic hyperamylasemia (Table 6).

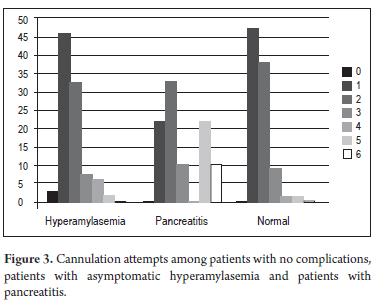

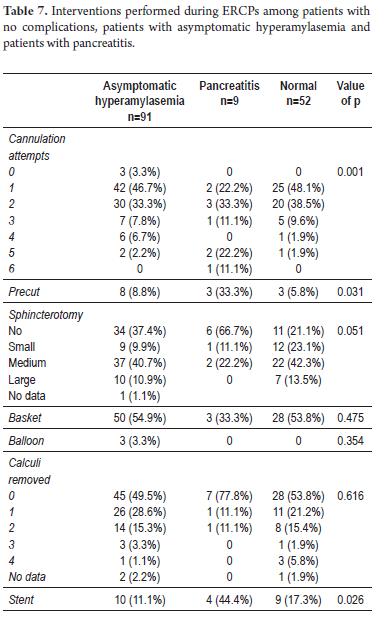

With regard to the interventions made during ERCP between patients who presented with asymptomatic hyperamylasemia and the normal group, there was a significantly higher percentage of cases who performed fewer than 5 attempts at cannulation (97.8% and 98.1% respectively) compared with those who presented with acute pancreatitis (66.7%) (p = 0.000) (figure 3).

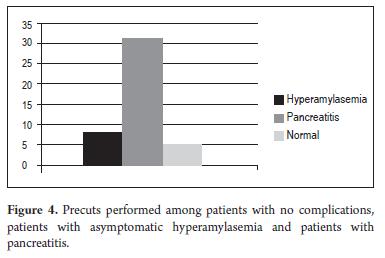

The percentage of patients who had a stent inserted was also significantly higher among the group with pancreatitis. A significantly higher proportion of patients who underwent papilla precuts later developed pancreatitis than did other patients who were stented (33.8 vs. 8.8%) (p<0.05) (Table 7, Figure 4).

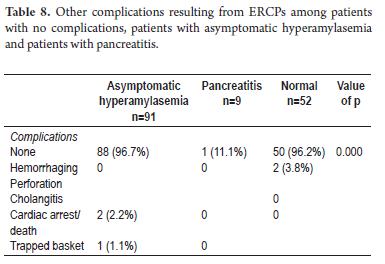

OTHER COMPLICATIONS RESULTING FROM ERCPS

In total, among all patients studied there were two cases of hemorrhaging (1.3%), two cases of cholangitis (1.3%) and 1 case of a trapped retrieval basket (0.6%). There were no cases of perforations or deaths resulting from the procedure (Table 8).

RISK ESTIMATES

Using the findings described above, Odds Ratios (ORs) were calculated for variables that showed some statistical association with the appearance of pancreatitis.

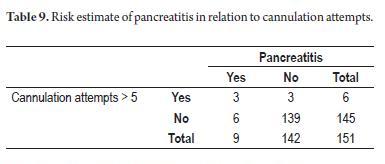

Of the six patients who had had 5 or more cannulation attempts 50% developed pancreatitis. According to the OR calculated for this variable, patients with 5 or more cannulation attempts had 23.16 time the risk of developing pancreatitis than did those patients who had undergone fewer cannulation att empts. This is a statistically significant association according to its 95% confi dence interval (CI): OR = 23.16, 95% CI= 3.84 to 139.71 (Table 9).

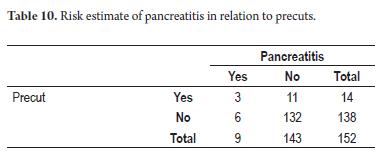

Patients upon whom the precut technique was used also had a risk of developing pancreatitis six times greater than did those patients who did not undergo this procedure. This association was also statistically significant according to its confidence interval: OR=6, 95% CI= 1.31 to 27.33 (Table 10).

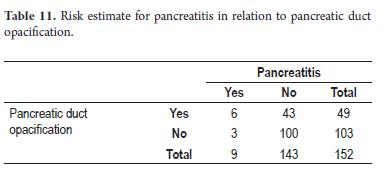

On the other hand, patients with pancreatic duct opacification had 4.65 times higher risk of developing pancreatitis than did those without opacification. The 95% confidence interval for this factor was also statistically significant: OR= 4.65, 95% CI = 1.11 to 19.46 (Table 11).

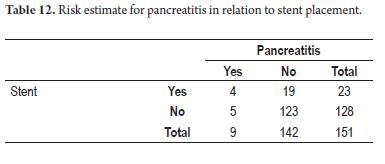

17.4% of the patients who received stents developed pancreatitis whereas only 3.9% of those who were not stented developed pancreatitis. Patients with stents had a 5.19 time greater risk of developing this complication than did patients who were not stented. This association is statistically significant: OR= 5.19, 95% CI=1.27 to 21.01 (Table 12).

DISCUSSION

Even in expert hands ERCPs are high risk procedures with a complication rate that varies between 5% and 10% in selected series and a mortality rate as high as 1% (1, 3, 5, 10). Acute pancreatitis, with an incidence varying between 1.8% and 7.2%, continues to be the most common and feared complication (1, 3, 11) Asymptomatic hyperamylasemia secondary to ERCP is much more frequent but fortunately has no risk for the patient. These two post ERCP clinical situations have great relevance to our daily practice: pancreatitis because of associated morbidity and mortality, and hyperamylasemia because of ignorance in our field about its frequency. This ignorance has led some physicians to mistakenly treat it is as pancreatitis. For these reasons, research is needed to establish risk factors associated with occurrence of pancreatitis and/or hyperamylasemia.

In this study, pancreatitis following ERCPs developed in 9 out of 152 patients (5.9%) while 91 out of 152 patients (59.8 %) developed asymptomatic hyperamylasemia. While the incidence found for pancreatitis is within the range described in the literature (1, 7, 8, 11), we found the incidence of hyperamylasemia to be much higher than those reported in studies such as that by Christoforidis et al. which reported an incidence of only 16.5% (1). While this has no relevance for patients with hyperamylasemia, it is important for clinical practice since, according to our study, almost 60% of the patients who underwent ERCPs will present hyperamylasemia without developing pancreatitis. This means that it is not necessary to keep them hospitalized, prohibit oral ingestion or to delay other treatments, such as performance of cholecystectomies, on these patients.

Even though some studies (1, 3, 12) have shown that women have higher risks for developing pancreatitis, these studies have not taken the clinical context or the technical difficulty of ERCP into account. Other studies have not found female sex to be an independent risk factor for development of following ERCP (2, 7, 13). Th e mechanism implied by this association remains speculative but might be greater frequency of dysfunctional sphincters of Oddi as shown by Freeman et al (2) Our research found a statistically insignificantly greater incidence of pancreatitis among female patients of p=0.895. This agrees with the above cited (1, 2, 7, 11, 15). We found no statistically significant diff erences in incidence of pancreatitis and/ or hyperamylasemia related to patients' ages. Although the traditional belief is that young people are at higher risk for this complication (1, 3, 16), most of the patients we receive in our ERCP center are older than 60 years of age. In addition patients are carefully selected for diagnostic ERCPs. These two factors may explain why age did not appear to be a risk factor in our study.

Of the clinical and paraclinical characteristics of patients prior to performance of ERCPs, cholelithiasis with suspected cholecholithiasis, accounting for 34.2% of the procedures, was the main reason the procedure was requested. Colicky abdominal pain prior to the procedure was present in 96% present of all cases while jaundice was present in 65% of all cases without any statistically significant diff erences among the 3 groups. The percentages of patients with elevated total and direct bilirubin in each of the three groups were very similar, p= 0.968. Th e absence of statistically significant differences contrasts with the differences reported in the literature (2, 11, 16-18). Th ose reports show that a low bilirubin level prior to the procedure is an independent risk factor for development of pancreatitis following ERCP. This may be due to its association with the presence of normal choledocal diameters (11, 16-19). However, it is important to highlight that in our study most of the patients who underwent ERCPs had dilated bile ducts which was a requirement for undergoing the procedure.

Technical variables are probably the most important factors in performance of an ERCP for avoiding consequent pancreatitis. This is why training is fundamental for the person who performs the procedure. Greater expertise results in fewer cannulation attempts, the bile duct rather than the pancreatic duct is opacified, and precut techniques are used less often (3, 20). Difficult cannulation is defined as those that require five or more attempts in order to gain access to the bile duct. This occurred in 6 patients, 50% of whom also developed pancreatitis. According to the risk estimate calculated for this variable, these patients had 23.1 times the risk of developing pancreatitis, a statistically significant association: OR= 23.16, 95% CI = 3.84 to 139.7. Th is is similar to reports in the literature (1, 3, 20) which demonstrate that the rate of pancreatitis increases with multiple cannulation attempts (1-3, 29). This may be caused by excessive local trauma and consequent edema that alters pancreatic draining (1, 13, 21). To control this factor, the training of the person performing the cannulation should be taken into account since the more procedures the gastroenterologist performs the better he or she will perform. Cannulation of the papilla by an experienced physician will likely require fewer attempts than when it is performed by an individual in training. ERCPs must be performed by a gastroenterologist who has been formally trained in this procedure in college. Doctors who take short courses and have no basic endoscopic dexterity should not jump in and perform ERCPs which is to have a high level of complexity in gastroenterology.

Use of precuts was required in 14 patients (9.21%). Although no perforations occurred, three of these patients developed pancreatitis (21.43%). There was a significantly greater proportion of these patients among those who developed pancreatitis following ERCPs: p<0.05. Th e risk estimate was 6 times greater for pancreatitis following ERCP with a statistically significant association: OR = 6, 95%CI = 1.31 to 27.3. This finding is related to that presented by other authors who report that precuts are a risk factor in univariate analyses. Unlike this report, those reports do not report precut technique as an independent risk factor (1-3, 17, 19). Nevertheless, we found no factors in our series that could explain this result. Th e probable mechanism whereby pancreatitis develops in this clinical scenario is temporary obstruction of the pancreatic duct caused by direct thermal damage (3, 9, 22), but the precut itself is probably not a factor in development of pancreatitis. Since we use precuts as a last resort after several cannulation attempts have failed to reach the bile duct, edema has already affected the papilla when this procedure is used. Some authors have shown that if one performs the precut at the start prior to any cannulation attempts then the incidence of pancreatitis does not increase (4, 11, 15, 23). Since this usage is not accepted, out group uses the precut as a final resort after standard cannulation fails.

Unintentional opacification of the duct of Wirsung occurred in 32% of the patients, among whom 36 (39.6%) developed hyperamylasemia while six of these patients (66.7%) were among the nine who developed pancreatitis and 7 (13.5%) were in the normal group. Th is group contained the largest number of patients who developed pancreatitis following ERCP with a statistically signifi cant relation of p=0.000. It was 4.65 times more probable for these patients to develop pancreatitis following ERCP: OR= 4.65, 95% CI 1.11 to 19.46. Since this risk factor for pancreatitis following ERCP has already been described in the literature (1, 3, 15, 24), it is important to highlight that it must be avoided at all costs. In our research the frequency of unintentional opacification of the duct of Wirsung was very high. The explanation is that hydrophilic guide wires were not used in some patients to ease the cannulation. This guide wire avoids the need to inject contrast dye to verify whether or not the papillotomy is in the common bile duct. When reviewing Colombian literature we found an incidence similar to the 28.5% reported by Peñaloza et al. Nevertheless, there was only one patient reported who had developed pancreatitis (15) in contrast to this study which establishes unintentional opacification as an independent risk factor more in line with the literature of the rest of the world (1, 8, 22) and with the pathophysiology of pancreatitis. Injection of contrast dye into the duct of Wirsung when attempting pancreatic acinarization during ERCP significantly increases pancreatic inflammation associated with hydrostatic lesions (1, 8, 23).

On the other hand, we have observed that the duct of Wirsung opacified in some patients even when a guide wire was used. This occurred because the papillotomy was too far away from the papilla. For this reason it is recommended that the papillotomy be placed within 2 to 3 cm of the papilla to avoid remaining in the common duct that communicates with the duct of Wirsung. Otherwise both ducts may opacify with a risk of pancreatitis following ERCP as high as the 4.6 times found in this study. Even though placement of pancreatic prostheses is completely accepted as a measure to protect against pancreatitis, none were used in this study because adequate prostheses were not available in our environment. Nevertheless, placing a prosthesis requires good training and has procedure costs both of which must be taken into account when considering this procedure (1, 3, 23).

Stents were used in the bile ducts of 23 patients (15.1%): ten (11.1%) had asymptomatic hyperamylasemia, four (44.4%) had pancreatitis, and 9 (17.3%) were in the normal group. Stents were used more often among patients who developed pancreatitis following ERCP than among other patients. The association was statistically significant with p=0.026). The risk of developing pancreatitis was 5.19 times greater among these patients: OR = 5.19, 95% CI = 1.27 to 21.01, making it an independent risk factor for development of pancreatitis. This association was not found in the literature reviewed (1, 3, 5, 11, 18, 22) which is why we need a prospective study to specifically explore this risk factor. Nevertheless, we know that when we place a stent in the common bile duct it usually causes significant trauma to the papilla and can indirectly occlude Wirsung's orifice. Both of these coincide theoretically with our results.

Cotton's international severity classification (5, 19) was used in our report of complications. The incidence of post ERCP pancreatitis in this study was 5.9% (9 of 152 patients). The 9 pancreatitis cases were mild no mortality resulted. Other complications were 2 cases of hemorrhaging (1.3%) and 2 other cases of post ERCP cholangitis. These findings are in line with those reported in other series (3, 11, 13, 14).

In conclusion, our study shows that post ERCP pancreatitis is a very frequent complication and asymptomatic hyperamylasemia is an even more frequent complication. Although asymptomatic hyperamylasemia does not have any implications for the patient, it does have important implications for clinical practice. One implication is our recommendation that for patients who do not have abdominal pain within the 24 hours following an ERCP, amylase tests should not be requested since it will be elevated in 60% of the cases, and because this information will not be useful for the doctor but may cause confusion leading to inappropriate actions already mentioned. The reason why some patients eventually develop post ERCP pancreatitis and not hyperamylasemia is still unknown. Identification of risk factors in our population is what is important. According to our investigation the most important factor is complicated cannulation (OR = 23.1, 95% CI 3.84 to 139.79). This procedure during ERCP should only be performed by a professional with formal training and a great deal of experience in this procedure. It is oft en better to abandon this procedure, try again at a later, opportunity, or evaluate the papilla to determine if it might be better to perform an early precut since later precuts have also proven to be a risk factor (OR = 6, 95% CI = 1.31 to 27.33). Opacification of the pancreatic duct (OR = 4.65, 95% CI = 1.11 to 19.46) must be avoided at all costs. We suggest that hydrophilic guide wires always be used to verify cannulation and deeply introduce the papillotomy before injecting contrast dye. Finally, we regard the use of a biliary stent (OR = 5.19, 95% CI = 1.27 to 21.01) to be a probable risk factor, although this is not well supported in the literature. Nevertheless, we recommend that it must be reserved for patients who have clear indications for its use.

REFERENCES

1. Christoforidis E, Goulimaris I, Kanellos I, Tsalis K, Demetriades C, Betsis D. Post ERCP pancreatitis and hyperamilasemia: patient related and operative risk factors. Endoscopy 2002; 34: 286-292.

2. Freeman ML, DiSario JA, Nelson DB, Fennerty B, Lee JG, Bjorkman DJ, Overby CS. Risk factors for post ERCP pancreatitis: a prospective multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc 2001; 54: 425-434.

3. Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber HG. Complications of endosopic biliary schinterotomy. N Engl J Med 1996; 335: 909-918.

4. Chi - Liang C, Foliente RL, Santoro MJ, Walter MH, Collen MJ. Risk factors post ERCP pancreatitis: a prospective multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101: 139-147.

5. Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes JA, Geenen JE, . Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc 1991; 37: 383-393.

6. Masci E, Toti G, Mariani A, Curioni S, Lomazzi A. Complications of diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP. A prospective multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol 2001; 96: 417-423.

7. Vandervoort J, Soetikno R, Tham T, Wong R. Risk factors for complications after performance of ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc 2002; 56: 652-656.

8. Cheng CL, Foliente RL, Santoro MJ, Walter MH. Risk factors for post ERCP pancreatitis: a prospective multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101: 139-147.

9. Testoni P, Mariani A, Giussani A, Vailati C, Masci E, Macarri G. Risk factors post ERCP pancreatitis in high and low volume centers and among expert and non expert operators: a prospective multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol 2010; 105: 1753-1761.

10. Elta GH, Barnett JL, Wille RT, et al. Pure cut electrocautery current for sphincterotomy causes less post procedure pancreatitis than blended current. Gastrointest Endosc 1998; 7 (2): 149-153.

11. Sherman S, Ruffolo TA, Hawes RH, Lehman GA. complications of endoscopic sphincterotomy. A prospective series with emphasis on the increased risk associated with non dilated bile ducts. Gastroenterology 1991; 101: 1068-1075.

12. Haber GB. Prevention of post ERCP pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc 2000; 51: 1- 5.

13. Sherman S, Lehman GA. ERCP and endoscopic sphincterotomy induced pancreatitis. Pancreas 1991; 6: 350-367.

14. Everson L, Artifon A, Chu A, Freeman ML, Sakai P, Usmani A. Comparison of the consensus and clinical definitions of pancreatitis with a proposal to redefine post ERCP pancreatitis. Pancreas 2010; 39: 530-535.

15. Peñaloza A, Leal C, Rodríguez A. Adverse events of ERCP at San Jose Hospital Bogota Colombia. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2009; 101 (12) 837-849.

16. BoenderJ,Nix GA,Ridder MA,Van Blankenstein M.Endoscopic papillotomy for common bile duct stones: factors influencing the complication rate. Endoscopy 1994; 26: 209-216.

17. Loperfido S, Angelini G, Benedetti G, Chilovi F, Costan F. Major early complications from diagnostic andtherapeutic ERCP: a prospective multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc 1998; 48: 1-10.

18. Dickinson RJ, Davies S. Post ERCP pancreatitis and hyperamylasaemia: the role of operative and patient. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1998; 10: 423-428.

19. Cotton PB. Precut papillotomy: a risky technique for experts only. Gastrointest Endosc 1989; 35: 578-579.

20. Baillie J. Complication of endoscopy. Endoscopy 1994; 26: 185-203.

21. Freeman M. Adverse outcomes of ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc 2002; 56: 273-282.

22. Cooper S, Slivka A. Incidence, risk factors, and prevention of post ERCP pancreatitis. Gastroenterol Clin N Am 2007; 36: 259-276.

23. Dumonceau J, Andriulli A, Deviere J, Mariani A, Rigaux J, Baron TH, Testoni P. European society of gastrointestinal endoscopy guideline: prophylaxis of post ERCP pancreatitis. Endoscopy 2010; 42: 503-515.

24. Tarnasky P, Cunningham T, Cotton P, Hoffman B, Palesch Y, Freeman T, et al. pancreatic sphincter hypertension increase the risk of post ERCP pancreatitis. Endoscopy 1997; 29: 252-257.

1. Christoforidis E, Goulimaris I, Kanellos I, Tsalis K, Demetriades C, Betsis D. Post ERCP pancreatitis and hyperamilasemia: patient related and operative risk factors. Endoscopy 2002; 34: 286-292. [ Links ]

2. Freeman ML, DiSario JA, Nelson DB, Fennerty B, Lee JG, Bjorkman DJ, Overby CS. Risk factors for post ERCP pancreatitis: a prospective multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc 2001; 54: 425-434. [ Links ]

3. Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber HG. Complications of endosopic biliary schinterotomy. N Engl J Med 1996; 335: 909-918. [ Links ]

4. Chi - Liang C, Foliente RL, Santoro MJ, Walter MH, Collen MJ. Risk factors post ERCP pancreatitis: a prospective multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101: 139-147. [ Links ]

5. Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes JA, Geenen JE, . Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc 1991; 37: 383-393. [ Links ]

6. Masci E, Toti G, Mariani A, Curioni S, Lomazzi A. Complications of diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP. A prospective multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol 2001; 96: 417-423. [ Links ]

7. Vandervoort J, Soetikno R, Tham T, Wong R. Risk factors for complications after performance of ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc 2002; 56: 652-656. [ Links ]

8. Cheng CL, Foliente RL, Santoro MJ, Walter MH. Risk factors for post ERCP pancreatitis: a prospective multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101: 139-147. [ Links ]

9. Testoni P, Mariani A, Giussani A, Vailati C, Masci E, Macarri G. Risk factors post ERCP pancreatitis in high and low volume centers and among expert and non expert operators: a prospective multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol 2010; 105: 1753-1761. [ Links ]

10. Elta GH, Barnett JL, Wille RT, et al. Pure cut electrocautery current for sphincterotomy causes less post procedure pancreatitis than blended current. Gastrointest Endosc 1998; 7 (2): 149-153. [ Links ]

11. Sherman S, Ruffolo TA, Hawes RH, Lehman GA. complications of endoscopic sphincterotomy. A prospective series with emphasis on the increased risk associated with non dilated bile ducts. Gastroenterology 1991; 101: 1068-1075. [ Links ]

12. Haber GB. Prevention of post ERCP pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc 2000; 51: 1- 5. [ Links ]

13. Sherman S, Lehman GA. ERCP and endoscopic sphincterotomy induced pancreatitis. Pancreas 1991; 6: 350-367. [ Links ]

14. Everson L, Artifon A, Chu A, Freeman ML, Sakai P, Usmani A. Comparison of the consensus and clinical definitions of pancreatitis with a proposal to redefine post ERCP pancreatitis. Pancreas 2010; 39: 530-535. [ Links ]

15. Peñaloza A, Leal C, Rodríguez A. Adverse events of ERCP at San Jose Hospital Bogota Colombia. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2009; 101 (12) 837-849. [ Links ]

16. BoenderJ,Nix GA,Ridder MA,Van Blankenstein M.Endoscopic papillotomy for common bile duct stones: factors influencing the complication rate. Endoscopy 1994; 26: 209-216. [ Links ]

17. Loperfido S, Angelini G, Benedetti G, Chilovi F, Costan F. Major early complications from diagnostic andtherapeutic ERCP: a prospective multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc 1998; 48: 1-10. [ Links ]

18. Dickinson RJ, Davies S. Post ERCP pancreatitis and hyperamylasaemia: the role of operative and patient. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1998; 10: 423-428. [ Links ]

19. Cotton PB. Precut papillotomy: a risky technique for experts only. Gastrointest Endosc 1989; 35: 578-579. [ Links ]

20. Baillie J. Complication of endoscopy. Endoscopy 1994; 26: 185-203. [ Links ]

21. Freeman M. Adverse outcomes of ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc 2002; 56: 273-282. [ Links ]

22. Cooper S, Slivka A. Incidence, risk factors, and prevention of post ERCP pancreatitis. Gastroenterol Clin N Am 2007; 36: 259-276. [ Links ]

23. Dumonceau J, Andriulli A, Deviere J, Mariani A, Rigaux J, Baron TH, Testoni P. European society of gastrointestinal endoscopy guideline: prophylaxis of post ERCP pancreatitis. Endoscopy 2010; 42: 503-515. [ Links ]

24. Tarnasky P, Cunningham T, Cotton P, Hoffman B, Palesch Y, Freeman T, et al. pancreatic sphincter hypertension increase the risk of post ERCP pancreatitis. Endoscopy 1997; 29: 252-257. [ Links ]

texto em

texto em