Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista colombiana de Gastroenterología

Print version ISSN 0120-9957

Rev Col Gastroenterol vol.27 no.3 Bogotá July/Sept. 2012

First Colombian Consensus on Digestive Endoscopy "Agreement on fundamentals" (First part: Formative aspects)

Diego Aponte Martín, MD (1), Camilo Blanco Avellaneda, MD, MSc (2), Nadia Sofía Flores, MD, MSc (3), Alix Yineth Forero Acosta, MD, MSc (4), Raúl Cañadas, MD (5), Arecio Peñaloza Ramírez, MD (6), Fabio Gil, MD (7), Fabián Emura, MD, PhD (8)

(1) Internist, Gastroenterologist and Endoscopist, President ACED. Bogotá, Colombia.

(2) Master's Degree in Education, Associate Instructor at the Universidad El Bosque, Tenured Professor at the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, MD Gastrointestinal Surgery and Digestive Endoscopy. Bogotá, Colombia.

(3) Master's Degree in Education, Tenured Professor at the Universidad La Gran Colombia, Research Advisor at the Centro Investigación de la Universidad Pedagógica, Credentialed in Childhood Education.

(4) Master's Degree in Education, Tenured Professor at the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Speech Therapist.

(5) Professor of Gastroenterology at the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Internist, Gastroenterologist and Endoscopist.

(6) Assistant Instructor in the Gastroenterology and Digestive Endoscopy Service at the Fundación Universitaria Ciencias de la Salud, Internist, Gastroenterologist and Endoscopist.

(7) Internist, Gastroenterologist and Endoscopist, former president of ACED. Clínica Colombia, Bogotá.

(8) Specialist in Gastroenterology and Digestive Endoscopy. Professor at the Universidad de la Sabana. Bogotá, Colombia.

Received: 24-04-12 Accepted: 17-08-12

Directors (or their representatives) of graduate programs in gastroenterology and digestive endoscopy, gastrointestinal surgery and digestive endoscopy, and coloproctology which are accredited in Colombia: Arango Lázaro (Universidad de Caldas); Hani Albis (Pontifica Universidad Javeriana); Oliveros Ricardo (Universidad Militar Nueva Granada - Instituto Naciónal de Cancerología); Peñaloza Ramírez Arecio (Universidad de Ciencias de la Salud); Rey Tovar Mario (Universidad del Rosario); Sabbagh Luis Carlos (Fundación Universitaria Sanitas); Salej Jorge (Universidad Militar Nueva Granada - Hospital Militar Central); Santacoloma Mario (Universidad de Caldas)

Presidents (or their representatives) of Digestive Disease Scientific Associations in Colombia: Aponte Diego (Asociación Colombiana de Endoscopia Digestiva); Archila Paulo Emilio (Asociación Colombiana de Medicina Interna); Galiano María Teresa (Asociación Colombiana de Gastroenterología); Ibáñez Heinz (Asociación Colombiana de Coloproctología); Landazábal Gustavo (Asociación Colombiana de Cirugía)

Former Presidents of Digestive Disease Scientific Associations in Colombia: Alvarado Jaime; Aponte Luciano; Cuello Eduardo; Gil Parada Fabio Leonel; Peñaloza Rosas Arecio; Plata Guillermo; Rojas Elsa; Roldán Luis Fernando

Vice President of the Asociación Iberoamericana de Enfermería en Gastroenterología y Endoscopia (ASIEGE): Ruiz Flor Alba

Train the Trainers World Organization of Gastroenterology: Emura Fabián; Valdivieso Rueda Eduardo; Vargas Rómulo

Professors and Opinion Leaders: Blanco Camilo; Cañadas Raúl; Solano Jaime; Unigarro Iván; Vélez Fausto

Chiefs of Accredited Gastroenterology Resident Programs: Casas Fernando (Surgeon); Herrán Martha (Internista); Imbeth Pedro (Internist); Suárez Juliana (Surgeon).

Abstract

Purpose of the work. The practice of endoscopy in Colombia was modified when Resolution 1043 of 2006 authorized specialists in general surgery, internal medicine and pediatrics to perform endoscopy after completing one year of training in endoscopy at an institution of higher education. This, together with the development of relationships with different specialties within endoscopy, generated a disordered scenario which many considered to be unjust and unequal. Training requirements became differentiated. A world of tensions and interests among specialists, scientists, health care providers and service providers led to this consensus. Starting with fundamental agreements, it makes recommendations for unification of educational features that will allow endoscopic practices which aim for quality and whose central axis is the best interest of our patients.

Materials and Methods. This consensus is a descriptive, cross-sectional social research study with a mixed approach (qualitative and quantitative) based on the Delphy method. The information in this study was obtained from the event titled "Acuerdo en lo fundamental" (agreement on fundamental issues) organized on June 23, 2012 by the president of the Colombian Association of Digestive Endoscopy (ACED). Qualitative data were taken from four roundtables discussions in which 34 participants discussed 25 survey questions. The quantitative data were taken from final voting and from an individual, private electronic survey. 75% or greater agreement was defined as consensus. Qualitative analysis employed discourse analysis oriented around five variables related to formative aspects. Basic descriptive statistics centered around percentages were used for quantitative analysis.

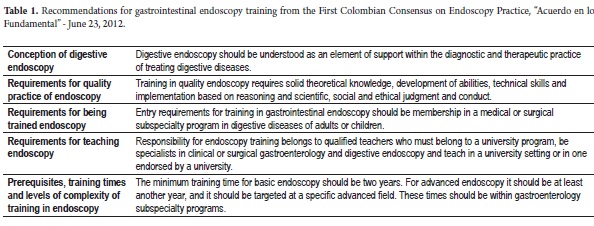

Results. Participants in the consensus included 34 directors or representatives of 8 of the 9 graduate university programs with specialties in the digestive tract, former presidents of 11 scientific associations, professors of gastrointestinal endoscopy, the vice president of the Ibero-American Nurses Association, directors of institutes of endoscopy, teachers at institutes of endoscopy and four chiefs of graduate resident programs. Some issues upon which consensus was reached include: 81.9% agreed that endoscopy is not simply a diagnostic technique; 88.2% disagreed with one year training as recommended for gastrointestinal endoscopy with quality parameters; 100% underlined that training in endoscopy should take place within qualified and accredited university teaching; More than 84.9% did not recommend training general practitioners, nurses or medical technicians in endoscopy; 85.3% recommended 2-year programs for basic training in endoscopy with 1 to 2 years for advanced endoscopy.

Conclusions. The Colombian consensus agrees that endoscopy is an element of support for both diagnostic and therapeutic practice. Training for quality endoscopy requires solid theoretical knowledge and skills, solid technical skills and knowledge and training in how to make ethical judgments. The basic requirement for training in gastrointestinal endoscopy should be that the student is enrolled in a clinical, surgical or pediatric gastroenterology subspecialty program. Responsibility for training in endoscopy should be in the hands of university professors and at well supported teaching hospitals and medical centers. The training time for basic endoscopy should be two years while advanced endoscopy requires at least another year and should be targeted towards a specific advanced field.

Key words

Endoscopy training, digestive diseases, endoscopy consensus, quality of endoscopy, Colombia.

INTRODUCTION

The scenario of gastroenterology and endoscopy practice in Colombia is very complex since it is determined by different conceptions, norms and interests.

Technical Appendix 1.1 (human resources) of Resolution 1043 of 2006 which sets out the conditions required of health service providers determines that gastroenterology and digestive tract endoscopy can be exercised by, "...physicians specializing in gastroenterology, pediatric gastroenterology, coloproctology, internal medicine with a subspecialty in gastroenterology, and pediatrics, pediatric surgery, general surgery and internal medicine who demonstrate certification of one year training in upper gastrointestinal endoscopy from an institution of higher learning recognized by the state." (1)

Law 1164 of 2007 which concerns Human Resources in Health care (2) and which was subsequently amended by Law 1438 of 2011 (3), determines, "...features regarding training, practice and management of health occupations." This must be consistent with the Colombian population and the characteristics and objectives of the general system of health care and social security defined in Law 100 of 1993 (4).

The exercise of the aforementioned laws, issued by the Ministry of Social Protection, complicates the scenario when determining the relationship that health care human resources must have in relation to the scenario of the Ministry of Education whose general guidelines, which touch upon graduate education, are stipulated in Law 30 of 1992 (5) and Law 115 of 1994 (6).

We can appreciate that the definition of formative features for the practice of gastroenterology and endoscopy were dictated from a setting different from that of education and prior to any consideration for the search for harmonious relations that working and teaching spaces must have especially in an area as sensitive as is the Colombian population's digestive health.

The apparent inconsistencies generated by these broad regulations have caused many tensions among specialists in different areas, among scientific associations, among the aforementioned ministries, among physicians who have travelled abroad to receive training, particularly in endoscopy, and who then return and seek recognition of their professional qualifications (ICFES), among those specialists who practice clinical and/or surgical) gastroenterology who study for a subspecialty, and among those who practice endoscopy after being specialists and receiving one year of training.

In the context of this reality we called for this consensus. We are convinced that gathering together all the representatives of the different scenarios that have arisen, especially those involved with endoscopic practice, will permit us to develop a B conceptual approach to the formative, ethical, educational and professional issues that should be reordered from the current situation. For this reason it has been called the, "Agreement on Fundamentals (Acuerdos Fundamentales)."

Therefore this study aims to demonstrate basic agreements that must be taken into account by government bodies. In the end these are the voices of the universities, the scientific associations and the highest scientific authorities who have built the last 50 years of history, and who are building the present, of gastroenterology and endoscopy of in Colombia.

This first part of our research focuses on the consensus achieved regarding the formative issues of gastrointestinal endoscopy.

GENERAL OBJECTIVE

To establish agreements on minimum basic issues that the training of specialists should have in order to exercise quality digestive endoscopy.

SPECIFIC OBJECTIVES

- To understand the concepts and scope of gastrointestinal endoscopy.

- To propose the knowledge, skills and training required prior to exercising quality endoscopy.

- To establish the characteristics required to be responsible for gastrointestinal endoscopy.

- To define what kind of professionals should be trained to perform digestive endoscopy.

- To propose times, prior training and levels of complexity that a specialist must have to perform quality endoscopy.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study type

Descriptive cross-sectional study with a mixed qualitative and quantitative approach

Participants

Those who were invited and who participated in the "Acuerdo en lo Fundamental" consensus were a nurse (vice president of an Ibero-American association of gastroenterological nursing), four graduate students (chief residents) from gastroenterology and endoscopy programs and 29 physicians (internists, general surgeons, gastroenterologists, coloproctologists, gastrointestinal surgeons) among whom were 8 of the 9 directors (or their representatives) of the accredited graduate programs in this country, five presidents (or their representatives) and 11 former presidents of associations of digestive tract disease sciences; professors; and professors and directors of endoscopy institutes who are considered to be opinion leaders.

The educational research group consisted of three people with Master's Degrees in Education and a research assistant who designed and implemented the study, did all data entry and analysis, and wrote this paper.

83% of participants were male and 17% were female, 80% were over 40 years old, 13% of the participants have practiced medicine for between 15 and 20 years, and 63 % have practiced medicine for more than 20 years.

Data Collection Techniques

The Delphy method for conducting consensus (7) was used for data collection. Within a scientific and humanistic environment experts expressed their views in a democratic debate. The conclusions defined as recommendations were independently and objectively developed based on the arguments expressed by all participants.

Two main variables (or dimensions) were defined: formation and ethics. In this article we are presenting the consensus reached with respect to the first variable "formative issues."

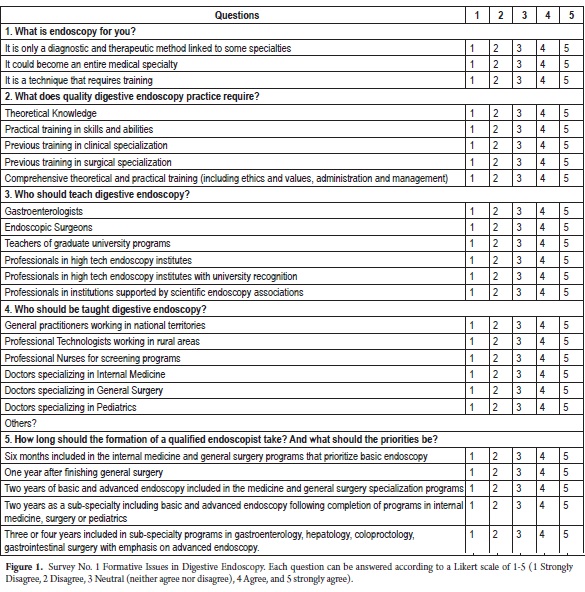

Survey No. 1 (Figure 1) was elaborated with 25 questions divided into five groups as secondary variables (or categories):

- Conception of digestive endoscopy

- Requirements for quality practice of endoscopy

- Responsibility for endoscopy training

- Candidates trained in endoscopy

- Prerequisites, training times and levels of complexity of training in endoscopy.

The survey was pilot tested twice with 8 gastroenterologists who belong to the Colombian Association of Digestive Endoscopy (ACED) who answered the survey individually and privately. Upon completion, clarity, relevance and intent of each question was discussed with each participant. Based upon their remarks, appropriate adjustments were made to produce the final survey.

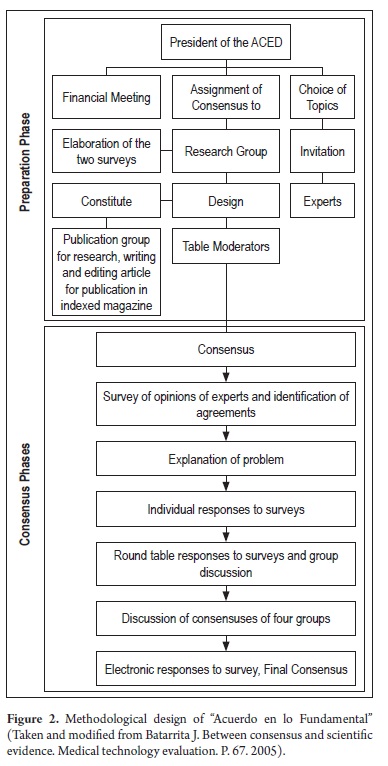

The activities at the four round tables to which the 34 participants were assigned were defined, and a moderator, a secretary and a research group counselor were appointed for each table.

The moderator was charged with developing the second part of the research model (Figure 2) which included explaining the problem and organizing the first step of having all of the participants answer the questionnaire individually in writing. Then the moderator organized the second step of the process which was the group discussion to attempt to reach a consensus. The following task for the moderator was to represent her or his group's consensus with the other three working groups. Finally, the moderator was charged with encouraging final responses to the third release of the survey. These responses were individual, private and electronic in order to avoid the effects of the leader's opinions in group discussion (8).

METHODOLOGY OF ANALYSIS

The quantitative part was handled with descriptive statistics focused on determining percentages. Consensus was considered after obtaining 75% or more of the total vote in the third release of the survey (electronic voting, individual and private). Finally three groups were settled to define the consensus: one corresponding to the sum of the percentages obtained as "Bly agree" and "Agree", the second to the sum of the percentages obtained as "Bly Disagree" and "Disagree" and the third group to the percentage obtained as "Neutral (neither agree nor disagree)."

The qualitative part was addressed from the content analysis method taking the round table discussions recorded in audio. The focus of the analysis was guided by the categories previously defined and discussed (9).

ETHICAL ISSUES

At the beginning of the entire data collection activity all participants were informed of the research objectives and consensus objectives, especially on the confidentiality with which data would be handled. Authorization was also requested in writing (by way of consent) so that all sessions (roundtables and general meetings of the whole group) could be recorded on audio and video. These records are secured and under safeguards.

RESULTS

The presentation of the consensus below is organized according to the aforementioned categories.

Questions and responses to questions are included for each graph. Statistical results greater than 75% in the final vote are highlighted in black. The ratings are shown in the figures. Graphs are followed by summaries of the arguments that led to the respective consensus with direct quotes indicated in the text. Arguments are the main axes of the qualitative content analysis.

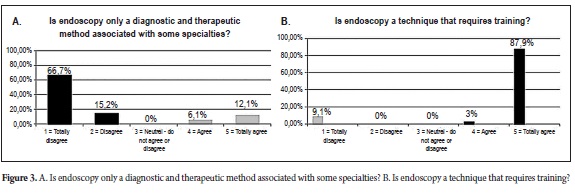

Figure 3 shows Category 1, the Concept of endoscopy, and the question based on this concept, what is endoscopy for you? This question sought to explore the nature of the general conception that participants had about endoscopy.

In Figure 3 consensuses of 81.9% and 90.9% were obtained regarding the conception and scope of gastrointestinal endoscopy. As one participant said, "...endoscopy is not simply sticking a tube in and pulling it out again, it's something integrated." In other words, endoscopy cannot be taken as a simple diagnostic or therapeutic method but rather is part of a broader concept of general medical and surgical knowledge of digestive diseases. The proper interpretation of results depends on the conceptual domain of the practitioner.

Similarly, endoscopy cannot be seen as only a simple, or even a very advanced, technique because its use requires comprehensive training in theoretical, practical and ethical issues. Performance of endoscopy on people implies having humanistic and quality considerations because, "...it includes the whole relationship with the patient, beginning with taking the patient's history and continuing until the outcome of the diagnosis." And, "...endoscopy is linked to a whole that is the overall approach to the patient. And, "...it is linked to the complete medical task."

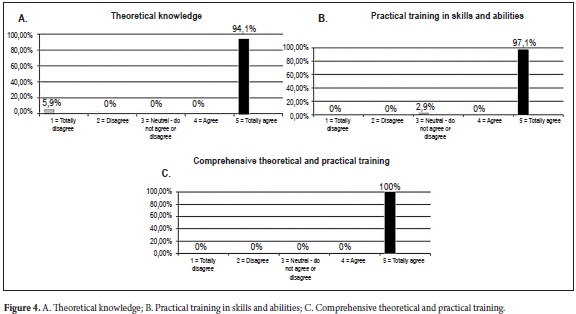

Figure 4 shows consensuses regarding the second category which explores academic, institutional and training requirements through the question, "What does the practice of quality digestive endoscopy require?

Figure 4 shows consensus of 94.1%, in favor of theoretical knowledge, 97.1% in favor of practical training in skills and abilities and 100% in favor of comprehensive theoretical and practical training.

For the participants talking about quality in the practice of endoscopy necessarily includes the domain of knowledge, abilities, "...developed with the help of the teacher," skills, "...perfected in the course of training and practice," and achievement of a, "...humanistic and ethical development that must be immersed in training programs since they are a central part of the professional practice."

Moreover, the technological development of endoscopy and high costs of instruments, tools, support and maintenance requires administrative and management skills, therefore training must transcend spaces which focus only on digestive diseases.

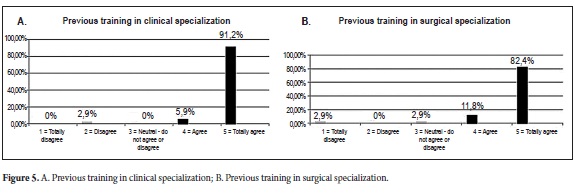

Figure 5 concerning the need to have clinical training or pre-surgical endoscopy training in accordance with current legal requirements, shows broad consensuses of 97.1% in favor of previous training in clinical specialization and 94.2% in favor of Previous training in surgical specialization. One participants said, "The surgeon must have the concepts and clinical knowledge, and the internist must have certain abilities and surgical skills." While another said, "However, current regulations require only one year of training in endoscopy so that specialties from general surgery, internal medicine or pediatrics can be part of the human talent needed to perform an endoscopy."

Currently Colombia has a double standard for training requirements because those who take a subspecialty in Gastroenterology or Surgical Gastrointestinal or Coloproctology are required to undergo two years of training in order to practice endoscopy.

It is agreed that ideally in the future, the law must demand prior training in digestive diseases, from the clinical or surgical standpoint in the specialties of gastroenterology, gastrointestinal surgical, pediatric gastroenterology or coloproctology. All of these face, to a greater or lesser degree, clinical and surgical challenges that require knowledge of how to overcome a wide spectrum of clinical and surgical problems. In addition legally required training time should be equitable.

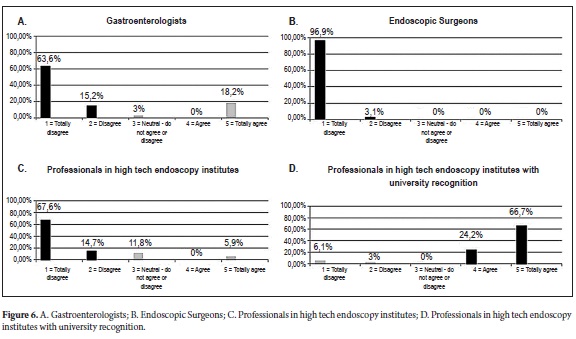

Figure 6 shows the consensuses regarding the third category which explored who should be people responsible for imparting training in endoscopy throughthe question, "Who should teach digestive endoscopy?

Figure 6 concerning who should teach digestive endoscopy shows consensuses of 78.8% in favor of gastroenterologists providing this training, 100% in favor of endoscopic surgeons providing this training, 82.3% in favor of professionals in high tech endoscopy institutes and 90.9% in favor of professionals in high tech endoscopy institutes with university recognition. Figure 6 does not endorse, per se, that these categories should teach endoscopy.

In contrast, the places where endoscopy is taught should have all the physical and pedagogical structure supported by university programs with qualified registration or accreditation. These features should target all institutions that aspire to be training sites, including high technology institutes. In other words, the formation processes cannot be above the law which clearly says that "...we should not have training programs outside of university programs."

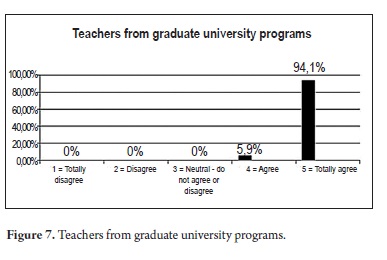

Figure 7 concerning who should teach endoscopy shows a 100% consensus. Following this logic, one who teaches "... should know what is going to be taught ... and know how to teach what will be taught ... according to the law."

Therefore, an endoscopy teacher must meet three requirements: "... be a university level professor, teach endoscopy within university programs, and teach within university medical centers".

The defense of these qualities seeks to safeguard against the risks of inadequate teacher training. Nevertheless, we cannot forget other factors related to the characteristics of each university such as whether or not a university places academic interest above money, and whether or not an institution has the real possibility of offering high technology and adequate sites for practice.

Not all programs can ensure these high quality requirements because, "... there are many garage universities with no technology, and that is a problem we cannot ignore."

The development of the teacher is an element that assumes fresh significance in relation to new needs and new technologies, "... you have to train educators. They need to have training and excellence in education." In particular, training should not be confused with formation because the connotations and degree of integrity, ethics, and humanistic conceptual learning required are different. "You can be in one place, you can build or teach a technique, but you may not have the ability to form endoscopists, one thing is to train and another is to form."

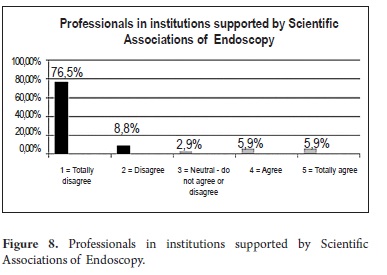

As shown in Figure 8, the possible role of scientific associations and accrediting institutions in relation to training programs does not generate positive consensus, "...because it is not their primary function ... they do not replace the role of the university, they should be providers and developmental agencies."

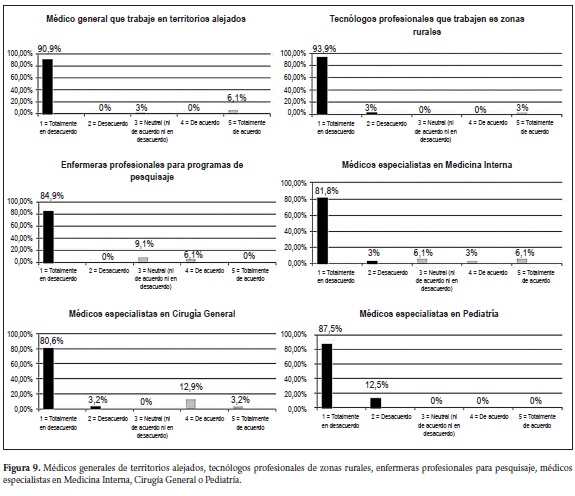

Figure 9 concerns the fourth category about who should taught digestive endoscopy, in other words who should be candidates for training and formation in endoscopy.

Figure 9 shows general consensuses of 90.9% against training general practioners working far from cities in endoscopy , 96.9% against training technicians in endoscopy, 84.9% against training professional screening nurses in endoscopy, 81.8% against training doctors specializing in internal medicine in endoscopy, 80.6% against training doctors specializing in general surgery in endoscopy and 100% against training doctors specializing in pediatrics in endoscopy. This opposition was specifically against performing procedures.

To be consistent with the consensus results from the first group of questions which understand endoscopy as an integral element of digestive disease management, these responses lead to a conclusion that neither non-medical personnel nor physicians without a special in areas directly related to digestive diseases are appropriate for solving endoscopic care issues even in the most remote areas of the country. Providing training in endoscpy to these groups would be neither fair nor just to the patients.

In fact, one participant thought that, "...this would be a social evil, this would be an antiethical thing ... this would be as if only from necesiity if there is no neurosurgeon in a remote area then we take a general practitioner to train in operating on aneurysms." One participant said that a person who uses the fact that she or he is working in a remote area to gain support to become an endoscopist, "... returns to the big cities to work the very day after receiving legal certification."

Even though it was understood that current law allows, "... the internist or general surgeon, with one year of training..." to practice endoscopy and "... provide a service to people in remote areas to which they have a right ... " we obtained a consensus that, in the future internists, surgeons and pediatricians should not be given this brief type of training.

For the sake of quality,which has ethical implications about the type of professional that provides endoscopic services, training in endoscopy should be exclusively for dcotors in a medical subspecialty in surgical or clinical gastroenterology or in adult or pediatric coloproctology. This will be shown in the following consensus. In any case, it was agreed that in places other than Colombia where general practitioners, nurses and health technicians play different roles, training them in endoscopy may have a place, especially in screening programs.

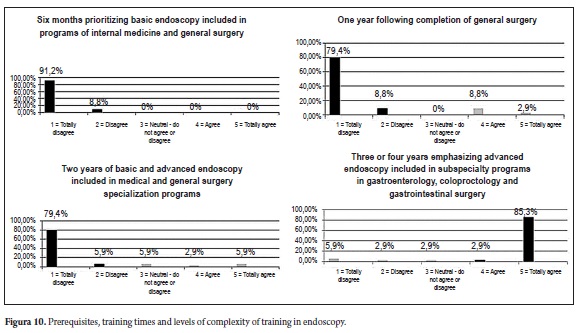

Figure 10 concerns the fifth category which explored the time, scope and training requirements needed prior to studying endoscopy through the questions, "How long should the formation of a qualified endoscopist take? And what should the priorities be?"

Figure 10 shows a consensus of 100% against recommending a 6 month training program for basic endoscopy within the general surgery and/or internal medicine programs. There was an 88.2% consensus against a 1 year training program in basic endoscopy after finishing general surgery, internal medicine or pediatrics, despite the fact that this is currently accepted by the law. There was an 85.3% consensus against two years of full time training in the internal medicine or surgery programs.

Although current regulations allow "... basic endoscopy for handling basic emergencies in outlying areas of Colombia to be performed by a surgeon with one year of training." the consensus is, "One year of training helps a physician look for gastritis, but it is not enough to interpret and handle emergencies." And, "... with basic training one can remove a foreign body or interpret where bleeding is located and what is causing it ... but it is not enough to make decisions or control endoscopic treatments." Instruction time is insufficient to provide the physician with the necessary elements for making more complex decisions or performing more complex actions.

The consensus considered that, given the current complexity of endoscopy, especially in its role as a diagnostic and therapeutic tool for treatment of patients with digestive diseases, quality training requires at least three years to approach the level of basic and advanced endoscopy when that training takes place within a subspecialty program of clinical or surgical gastroenterology. "Technological development and knowledge of endoscopy have enabled progress and the emergence of new techniques which require specific training and dedication in every area."

Thus, basic endoscopy may be learned sufficiently well in two years, but at least one more year is required to reach an advanced level, but this must always (over and over) be within programs only for "gastroenterologists, gastrointestinal surgeons, proctologists, eventually pediatric gastroenterologists and pediatric surgeons, "...and within university programs with qualified registration or accreditation.

The third or fourth year which include advanced endoscopic approaches should focus on ERCP, endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR or mucosectomy), endosonography, enteroscopy, prosthetics and other areas because it is logical that, "The commitment is to focus on a specific field and do very well in that field." Until more specialized medical centers are developed in Colombia, in addition to those that now exist, training outside of the country will remain the primary alternative for specific fields of advanced endoscopy.

Finally, the realities of professional practice and training in digestive endoscopy today mean that increased time and prerequisite for training in endoscopy have the provision of greater benefits for patients and society as their principal aim.

DISCUSSION

The Real Academia Española (Royal Academy of the Spanish Language) defines consensus as, "Consensual agreement produced amongst members of a group." (10) This occurs through consultations or expert commissions which seek decisions or agreements in diverse social or professional situations whenever there may be differences that somehow create tensions damaging an otherwise a harmonious environment.

With this and with the perception of some difficulties in the practice of gastrointestinal endoscopy, the Colombian Association of Digestive Endoscopy (ACED) gathered a group of experts for the first Colombian consensus called the "Acuerdo en lo Fundamental." Its results have been presented above. The research findings have provided evidence of conceptual, educational, professional and ethical issues that cut across the different actors and contexts of training in gastrointestinal endoscopy in Colombia.

After expressing the legal, academic and working complexity of gastrointestinal endoscopy, as well as its occasional disorganization, the study has made clear that the reality is that the goals of training are not being met with full profile physicians practicing gastrointestinal endoscopy. National training programs for specialization in gastroenterology define those goals for the graduate profile as forming, "...leadership specialists with skills to impart knowledge and develop research programs..." with extensive knowledge in digestive system skills, and, "...to understand, learn and implement various technological advances in gastrointestinal endoscopy." (11, 12) An entry requirement for all programs in the country is that the student be a specialist in internal medicine and/or general surgery. Until 2006 the practice of endoscopy was authorized only for graduates of these programs, with endoscopy being understood as an important, but not central or final, medical practice related to digestive diseases.

The current consensus reached agreements showing the impertinence of accepting training times for endoscopy of only one year following a general specialization. It shows the relevance of scientific, technological, social and ethical implications for requiring basic endoscopy training time of not less than two years, and total training time of between 3 and 4 years for advanced endoscopy. In both cases, training must always be part of a clinical gastroenterology, clinical pediatric gastroenterology, gastrointestinal surgery, coloproctology, or pediatric surgery sub-specialty in accordance with international standards (13, 14, 15).

These formative features are supported by the importance of development of cognitive abilities and technical skills in procedures related to digestive diseases and by the capacity required of the physician to interpret a digestive condition and design an appropriate approach for treatment, recovery or rehabilitation (13). A positive consensus was also reached on the importance of explicitly introducing training activities related to ethics, values, administration and management.

The consensus has not ignored the law currently in force in Colombia in 2012. Those laws allow general surgeons or internists with a 1 year training supported by a university to perform an endoscopy. The consensus did not ignore the governmental motivation for authorizing this type of practice. It approach s motivation was based on criteria of universality, equity and equality which are defined as principles in the Health and Social Security System because of an apparent or actual shortage of specialists in this area (Article 153 of Law 100 of 1993 and Article 3 of Law 1438 of 2011).

The consensus has proposed, as opposed to these postulates, another principle of the same system and aforementioned laws: the principle of quality. There have been many demonstrations which led to the consensus which has been reached for recommending against continuing the practice of endoscopy, even of basic diagnostic endoscopy, with so little preparation time. This practice is not moral or ethical because its alleged fairness and equality cannot assure patients whether or not the practitioner has adequate and sufficient preparation according to the opinion of the greatest gastroenterology experts in the country.

The central criterion for endorsing endoscopy training as adequate is not certification in a specific number of procedures (15). Rather, supervised, followed up, academic and technological study and research are required to turn a certain number of procedures into evidence of really adequate training. This is formative evidence that in truth becomes an instrument that generates social justice.

These considerations regarding prerequisites and minimum formation times did not arise out of prejudices or apriori judgments. These are the observations and reflections of teachers and professionals, most of whom have over 20 years of teaching experience and work. For these experts the center of the discussion is the understanding what endoscopy is.

The consensus broadly rejected viewing endoscopy as a specialty independent of digestive disease specialties. They also do not perceive it to be a simple technique which can be indiscriminately applied by other specialties when they focus on other digestive diseases. Instead, digestive endoscopy is seen as part of comprehensive training in the gastroenterological specialties previously mentioned.

In this sense the consensus was careful not to assign responsibility of endoscopic formation to practice centered techniques, even if they are highly specialized. Neither economic nor technological resources can replace or displace the comprehensive training provided by gastroenterology and endoscopy teachers. Those teachers should be prepared according to the existing programs for educational qualification at universities and elaborated by international scientific associations.

Discussions in international bodies such as the American Association of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (AAGE) and the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) begin with an established core curriculum and focus on training and quality issues such as holistic understanding of endoscopy, biosecurity compliance, improved interpretation of endoscopic findings, identification of risk factors, limitations of procedures and quality measures. (14, 15) In contrast, her in Colombia we must still resolve challenges that are not strictly related to training, patient care and research, but have other concerns such as the type of recruitment system for intermediaries and the definition of tariff floors.

Nevertheless, it is the responsibility of all parties to resolve differences regarding the formative dimension in endoscopy. Everyone involved in medical practice has a moral and ethical duty to go beyond interests which remove our attention from ensuring the integral welfare of our patients.

CONCLUSIONS

The main agreements of this consensus are shown in Table 1. They postulates demand to be heard and seen by government agencies, academia, universities, scientific associations, health care institutions, and especially by the medical professionals upon which much of the integral and gastroenterological health of Colombians rests.

REFERENCES

1. Resolución que establece las condiciones que deben cumplir los Prestadores de Servicios de Salud para habilitar sus servicios e implementar el componente de auditoría para el mejoramiento de la calidad de la atención y se dictan otras disposiciones. República de Colombia. Ministerio de Protección Social. Resolución No. 1043 de 2006.

2. Talento humano en salud. Ley 1164 de 2007. Ley Pub. No. 1164 de 2007. Congreso de Colombia; 2007 (Octubre 3 de 2007).

3. Reforma el Sistema General de Seguridad Social en Salud y se dictan otras disposiciones. Ley 1438 de 2011. Ley Pub. No. 1438 de 2011. Congreso de Colombia; 2011(Enero 19 de 2011).

4. Sistema de Seguridad Social Integral. Ley 100 de 1993. Ley Pub. No. 100 de 1993. Congreso de Colombia; 1993 (Dic. 23 de 1993).

5. Organiza Servicio Público de la Educación Superior de la República de Colombia. Ley 30 de 1992. Ley Pub. No. 30 de 1992.Congreso de Colombia; 1992 (Dic. 28 de 1992).

6. Ley general de Educación de la República de Colombia Ley 115 de 1994. Ley Pub; 1994 (Febrero 8, 1994).

7. Astigarraga E. Método Delphy. Universidad de Deusto San Sebastián. (citado 1 de Junio de 20012) (s.f.). Disponible en URL: http://www.echalemojo.com/uploadsarchivos/metodo_delphi.pdf. Consultado 01 de junio de 2012.

8. Batarrita JA. Entre el consenso y la evidencia científica. Gac Sanit 2005; 19(1): 65-70.

9. Gil F. Análisis de datos cualitativos. Aplicaciones a la investigación educativa "El análisis de datos cualitativos" Aproximación interpretativa al contenido de la información textual. Barcelona: PPU, S.A.; 1994. p. 31‐63.

10. Real Academia de la Lengua Española. Consenso (Serial en línea) (citado 16 de julio 2012). Disponible en: http://lema.rae.es/drae/. Consultada 16 de julio de 2012.

11. Fundación Universitaria Sanitas. Organización sanitas internacional. Especialización en gastroenterología y endoscopia digestiva. Disponible URL: http://www.unisanitas.edu.co/index.php/gastroenterologia-y-endoscopia-digestiva. Consultada 9 de julio de 2012.

12. Universidad del Rosario. Escuela de medicina y ciencias de la salud. Especialización en gastroenterología. Disponible: http://www.urosario.edu.co/EMCS/Especializaciones/gastroenterologia/ Consultada 9 de julio de 2012.

13. González JA, y cols. ¿El adquirir una habilidad técnica, es suficiente para realizar la endoscopia digestiva? Una reflexión de la experiencia de un centro de entrenamiento universitario. Revista de Gastroenterología de México 2011; 76(1): 1-5.

14. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE). Principles of training in GI endoscopy. Report on training 2012; 75(2): 231- 235.

15. Taullard D. Mejor calidad de la endoscopia digestiva. Capacitación y certificación. La Sociedad Interamericana de Endoscopia Digestiva (SIED). Foro Latinoamericano de Endoscopia Digestiva (FLAED) Dr. Roque Sáenz /2M Impresores: Chile; 2010. p. 20-28.

1. Resolución que establece las condiciones que deben cumplir los Prestadores de Servicios de Salud para habilitar sus servicios e implementar el componente de auditoría para el mejoramiento de la calidad de la atención y se dictan otras disposiciones. República de Colombia. Ministerio de Protección Social. Resolución No. 1043 de 2006. [ Links ]

2. Talento humano en salud. Ley 1164 de 2007. Ley Pub. No. 1164 de 2007. Congreso de Colombia; 2007 (Octubre 3 de 2007). [ Links ]

3. Reforma el Sistema General de Seguridad Social en Salud y se dictan otras disposiciones. Ley 1438 de 2011. Ley Pub. No. 1438 de 2011. Congreso de Colombia; 2011(Enero 19 de 2011). [ Links ]

4. Sistema de Seguridad Social Integral. Ley 100 de 1993. Ley Pub. No. 100 de 1993. Congreso de Colombia; 1993 (Dic. 23 de 1993). [ Links ]

5. Organiza Servicio Público de la Educación Superior de la República de Colombia. Ley 30 de 1992. Ley Pub. No. 30 de 1992.Congreso de Colombia; 1992 (Dic. 28 de 1992). [ Links ]

6. Ley general de Educación de la República de Colombia Ley 115 de 1994. Ley Pub; 1994 (Febrero 8, 1994). [ Links ]

7. Astigarraga E. Método Delphy. Universidad de Deusto San Sebastián. (citado 1 de Junio de 20012) (s.f.). Disponible en URL: http://www.echalemojo.com/uploadsarchivos/metodo_delphi.pdf. Consultado 01 de junio de 2012. [ Links ]

8. Batarrita JA. Entre el consenso y la evidencia científica. Gac Sanit 2005; 19(1): 65-70. [ Links ]

9. Gil F. Análisis de datos cualitativos. Aplicaciones a la investigación educativa "El análisis de datos cualitativos" Aproximación interpretativa al contenido de la información textual. Barcelona: PPU, S.A.; 1994. p. 31‐63. [ Links ]

10. Real Academia de la Lengua Española. Consenso (Serial en línea) (citado 16 de julio 2012). Disponible en: http://lema.rae.es/drae/. Consultada 16 de julio de 2012. [ Links ]

11. Fundación Universitaria Sanitas. Organización sanitas internacional. Especialización en gastroenterología y endoscopia digestiva. Disponible URL: http://www.unisanitas.edu.co/index.php/gastroenterologia-y-endoscopia-digestiva. Consultada 9 de julio de 2012. [ Links ]

12. Universidad del Rosario. Escuela de medicina y ciencias de la salud. Especialización en gastroenterología. Disponible: http://www.urosario.edu.co/EMCS/Especializaciones/gastroenterologia/ Consultada 9 de julio de 2012. [ Links ]

13. González JA, y cols. ¿El adquirir una habilidad técnica, es suficiente para realizar la endoscopia digestiva? Una reflexión de la experiencia de un centro de entrenamiento universitario. Revista de Gastroenterología de México 2011; 76(1): 1-5. [ Links ]

14. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE). Principles of training in GI endoscopy. Report on training 2012; 75(2): 231- 235. [ Links ]

15. Taullard D. Mejor calidad de la endoscopia digestiva. Capacitación y certificación. La Sociedad Interamericana de Endoscopia Digestiva (SIED). Foro Latinoamericano de Endoscopia Digestiva (FLAED) Dr. Roque Sáenz /2M Impresores: Chile; 2010. p. 20-28. [ Links ]

text in

text in