Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista colombiana de Gastroenterología

versión impresa ISSN 0120-9957

Rev Col Gastroenterol vol.28 no.1 Bogotá ene./mar. 2013

First Colombian Consensus on the Practice of Endoscopy âFundamental Agreementâ

(Part two: Ethics)

Camilo Blanco Avellaneda, MD. (1), Diego Aponte Martín, MD. (2), Alix Yineth Forero Acosta, MD. (3), Nadia Sofía Flores, MD. (4), Raúl Cañadas, MD. (5), Arecio Peñaloza Ramírez, MD. (6), Fabio Leonel Gil, MD. (7), Fabián Emura, PhD. (8)

(1) Master's in Education, Associate Professor at the Universidad El Bosque, Professor at the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, MD in Gastrointestinal Surgery and Endoscopy

(2) Internist, Gastroenterologist, and Endoscopist, President of ACED

(3) Master's in Education, Professor at the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Speech therapist

(4) Master's in Education, Professor at the Universidad La Gran Colombia, Educational Research Advisor at the Centro de Investigaciones de la Universidad Pedagógica Nacional, Credentialed for Childhood Education

(5) Professor of Gastroenterology at the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Internist, Gastroenterologist, and Endoscopist

(6) Assistant Professor in the Gastroenterology and Digestive Endoscopy Service of the Fundación Universitaria Ciencias de la Salud, Internist, Gastroenterologist, and Endoscopist

(7) Internist, Gastroenterologist and Endoscopist, Former President of the Asociación Colombiana de Endoscopia Digestiva

(8) PhD, Specialist in Gastroenterology and Digestive Endoscopy, Associated Professor of the Medicine Faculty at the Universidad de La Sabana.

Received:08-10-12 Accepted: 31-01-13

Directors (or their representatives) of graduate programs in gastroenterology and digestive endoscopy, gastrointestinal surgery and digestive endoscopy, and coloproctology which are accredited in Colombia: Arango Lázaro (Universidad de Caldas); Hani Albis (Pontifica Universidad Javeriana); Oliveros Ricardo (Universidad Militar Nueva Granada Instituto Naciónal de Cancerología); Peñaloza Ramírez Arecio (Universidad de Ciencias de la Salud); Rey Tovar Mario (Universidad del Rosario); Sabbagh Luis Carlos (Fundación Universitaria Sanitas); Salej Jorge (Universidad Militar Nueva Granada Hospital Militar Central); Santacoloma Mario (Universidad de Caldas)

Presidents (or their representatives) of Digestive Disease Scientific Associations in Colombia: Aponte Diego (Asociación Colombiana de Endoscopia Digestiva); Archila Paulo Emilio (Asociación Colombiana de Medicina Interna); Galiano María Teresa (Asociación Colombiana de Gastroenterología); Ibáñez Heinz (Asociación Colombiana de Coloproctología); Landazábal Gustavo (Asociación Colombiana de Cirugía)

Former Presidents of Digestive Disease Scientific Associations in Colombia: Alvarado Jaime; Aponte Luciano; Cuello Eduardo; Gil Parada Fabio Leonel; Peñaloza Rosas Arecio; Plata Guillermo; Rojas Elsa; Roldán Luis Fernando

Vice President of the Asociación Iberoamericana de Enfermería en Gastroenterología y Endoscopia (ASIEGE): Ruiz Flor Alba

Train the Trainers â World Organization of Gastroenterology: Emura Fabián; Valdivieso Rueda Eduardo; Vargas Rómulo

Professors and Opinion Leaders: Blanco Camilo; Cañadas Raúl; Solano Jaime; Unigarro Iván; Vélez Fausto

Chiefs of Accredited Gastroenterology Resident Programs: Casas Fernando (Surgeon); Herrán Martha (Internista); Imbeth Pedro (Internist); Suárez Juliana (Surgeon).

QR. code

Father Llano speech.

Abstract

Purpose: The practice of endoscopy involves theoretical, practical and ethical knowledge. The first two are given widespread distribution and great importance in education. Ethics is always mentioned, but is little studied or investigated. The Colombian Association of Digestive Endoscopy (ACED) devotes the second part of the âFundamental Agreementâ consensus to the ethical practice of gastrointestinal endoscopy. We approach this topic from an analysis of the resolution of real dilemmas that arise in endoscopic scenarios shaping our practice. This is the way of conceptually appropriating ethical principles and moral values that should permeate the practice of specialists who rely on endoscopy. It is important to note that the end result is not intended to standardize the conduct of doctors. To the contrary, we propose to carry out an ongoing reflection about the continuous conflicts that arise in our specialty which should not be resolved without profound ethical and moral consideration.

Materials and methods: This consensus is a social research study. It uses a descriptive and cross-sectional approach which mixes qualitative and quantitative analysis and is based on the Delphi Method. The information used was obtained during the âFundamental Agreementâ event held on June 23, 2012 by the Colombian Association of Digestive Endoscopy (ACED). Qualitative data were taken from four roundtable discussions in which the 34 participants discussed the 21 proposed ethical dilemmas. Quantitative data used include the final voting, individual private electronic surveys. Consensus was defined as agreement of 75% or more of participants. Speech analysis was used for qualitative analysis. It was oriented around from five variables related to moral and ethical aspects of the practice of endoscopy. For quantitative analysis, basic descriptive statistics centered on percentages were used.

Results: Some of the consensus obtained were: 80.65% agreed to consult with the group that they replace in a particular institution; 80.54% shared the opinion that the type of contract limited research, educational, institutional and even personal development; 78.12% agreed that recognition of group work prevails over recognition of individual work in intellectual production, 100% agreed every individual involved in writing and publication should receive individual credit for their work; 80.64% agreed that the relationship of the patient to the health system determined the kind of attention that is given, and 90.82% agreed that the quality of care was affected by the number of patients who require care.

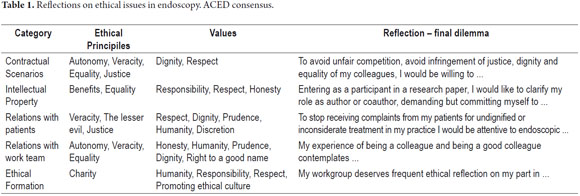

Conclusions: The Colombian consensus agrees that resolution of ethical dilemmas that arise in real-world scenarios in the practice of endoscopy should consider ethical and moral values specifically related to the particular situation faced by the specialist. Thus, conflicts related to contractual or employment issues have to consider the dignity of, and respect for, colleagues. Similarly, equality and justice as values and principles that prevail within these scenarios must be considered. Intellectual property rights require responsibility and honesty as guiding principles when situations of group or individual recognition are confronted. Endoscopists' professional relationships with patients should be framed within values and ethics including prudence, humanity, truthfulness, and choosing the lesser evil. In turn, the specialist's relations with her or his team should respect collegiality, autonomy, the right to an individual's good name, dignity and equality. A culture that promotes ethics, responsibility, humanity and charity must prevail for ethical training.

Key words

Ethical principles, moral values, consensus on endoscopy, ethics in gastroenterology and endoscopy, training in ethics, medical ethics, Colombia.

INTRODUCTION

This report contains the second part of the findings at the First National Consensus âAgreement on Fundamentalsâ on the practice of digestive endoscopy in Colombia. The consensus was organized by the Colombian Association of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and held on June 23 of 2012 in Bogotá.

The first part of this study, published in October 2012, presented the agreements in terms of basic minimal issues to keep in mind during the formation of specialists for the practice of high quality endoscopy. Five points for implementation were agreed upon. First, endoscopy should be understood as a support element within the practice of diagnostic and therapeutic management of digestive diseases. Second, training in quality digestive endoscopy requires solid knowledge, skills and technical aptitudes. It requires implementation of judgment, reasoning and scientific, social and ethical behavior. Third, formation as an endoscopist requires access to digestive endoscopy training including a subspecialty program (medical or surgical) for adult or childhood digestive diseases. Fourth, the responsibility for formation of a digestive endoscopist should be in the hands of qualified teachers who are part of a university program, who are specialists in medical or surgical gastroenterology and digestive endoscopy, and who teach in a university setting or in a setting supported by a university. Finally, the minimum training time for basic digestive endoscopy should be two years; with at least one additional year of training in a specific advanced field for advanced endoscopy. Subspecialty gastroenterology programs should comply with these time periods (1).

This report focuses on the second stage of the consensus which investigated ethical issues concerning the exercise of gastrointestinal endoscopy. Although this was a novel exercise for the participants since this is not an issue that is addressed in the vast majority of academic activities, it was relevant to the participants because there are many medical decisions in endoscopy which touch upon ethical and moral issues.

Ethics in gastroenterology and digestive endoscopy was approached by the consensus from different perspectives: some centered on theory, others on practice.

The theoretical perspective emphasizes recent analyses which breakdown conceptions of ethics so that we can now distinguish between the ethics of direct patient care and research ethics, and ethics regarding knowledge that is generated through research. Ethics regarding knowledge generated through research is particularly important because it questions the âendoscopic epistemologyâ of generation, acceptance and validity of knowledge which is threatened by the particular interests of the pharmaceutical and medical equipment companies (2).

At the same time the practical perspective approaches ethics from the point of view of resolving ethical dilemmas, many of which are found in the exercise of e specialties that use endoscopy. There are at least 10 specific medical issues that can be listed. They include obtaining informed consent forms for specific procedures, consent and the capacity to consent, speaking the truth, quality care at the end of life, conflicts of interest in patient care, management of gastrointestinal malignancies, ethics and education in research ethics, ethical issues in artificial nutrition, euthanasia and assisted suicide. These are matters for discussion, reflection and moral and ethical decision making. The order of their significance and importance changes over time for the practitioner as he or she moves through life from being a graduate student to a practicing specialist and as the reality of practice modifies the relevance of each dilemma (3).

In our environment medical actions are conceptually framed in precise regulations. Chapter VI of Law 1164 of 2007, âBy which is established provisions concerning human resources in health care,â is dedicated to âethics and bioethics in the provision of services.â Articles 34 to 38 emphasize, â... respectful care of the life, dignity of every human being, and promotion of existential development ... without distinction of any kind ... â It also requires that, â... the conduct of those who practice a profession or occupation in health care must be within the limits of the code of ethics of their profession or occupation and the general rules that apply to all citizens under the Constitution and the Lawâ(4).

According to Fernando Sánchez Torres (5), medical ethics is, â... the discipline that deals with the study of medical acts from the moral point of view ...â He describes them as good or bad as long as they are conducted in a voluntary, conscious and individual form. He says that medical ethics are structured and systematized like a building that, â... has foundations, walls and finishings ...â which he says correspond, to general ethical principles, moral values and laws, a building constructed on the âfertile and necessary ground ...â which is mankind, who is at the same time the architect of his own being and of his ethically responsible behavior. Thus, ethical principles are attached to moral principles which Sanchez defines as, âthose that enable or facilitate acts to be good.â When you appeal to these principles, they acquire the same importance as, â... when science appeals to a law.â Principles turn into â... authorized actions whose consequences are better than any that may arise from any other alternative action.â Thus seen, the general and inclusive character acquired by both general ethical principles such as autonomy, justice, beneficence, and non-malevolence and by principles such as truth, equality, choosing the lesser evil, totality, and the principle of double effect which are associated with medical procedures can be understood (5).

On the other hand, we also understand values as qualities that possess some reality, what Sanchez calls âgoods,â and these too are worthy of esteem. For a quality to be accepted as a âmoral value,â Sanchez says it must comply with certain requirements, including having a value even though something is intangible. Other requirements include objectivity, polarity, quality and hierarchy. Despite the fact that something such as generosity is not tangible, it can be desirable, valuable and understandable. Polarity means that a value has a negative value, e.g. honesty and dishonesty while the quality of a value such as prudence is its defining asset even though it cannot be quantified. Hierarchy means that there are higher and lower degrees of values such as equality, humanity and consideration that allow us to rank them on a table that serves as a permanent incitement to moral uplift (5). This is how we understand the significance and importance of values that characterize ethical medical procedures.

As the intent of this study is not to focus the discussion on theoretical aspects of general and medical ethics which have been discussed elsewhere, this research focused its inquiry in reflection on the resolution of ethical dilemmas present in real endoscopy scenarios. These situations extended beyond those strictly related to patient care to approach problematic facts in scenarios wherever endoscopy is practiced in this country including work, training and research.

The reflection fostered, and the consensus achieved, concerning the 21 dilemmas presented constitute a general reference framework in which to unfold the moral and ethical practice of specialties that deal with endoscopy. From the inclusive posture of this framework the participants underlined, apart from their personal feelings, forms of consensus of âa social beingâ that can permeate behavior and constitute recommendations for other areas of medical practice.

GENERAL OBJECTIVE

The general objective was to reach consensus on basic issues concerning minimum and basic ethical principles and values with which the dilemmas in medical practice can be addressed by specialists who practice disciplines related to digestive endoscopy.

Specific Objectives

- Identify behaviors and attitudes when facing ethical dilemmas in different contractual situations.

- Establish considerations about respecting intellectual property rights over work in digestive endoscopy.

- Characterize the principles and values that guide current relations among specialists and patients.

- Give meaning to interactions that occur within work teams.

- Recognize the importance of training in ethical principles and values for practicing digestive endoscopy.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Type of study

Descriptive cross section study with a mixed qualitative and quantitative approach

Participants

Invited participants who attended the first Colombian consensus on the practice of gastrointestinal endoscopy âAgreement on Fundamentalsâ included a nurse who is the vice president of a Latin American association of gastroenterological nursing, four chief residents who are postgraduate students in gastroenterology and digestive endoscopy programs, and 29 physicians who include internists, general surgeons, gastroenterologists, coloproctologists, and gastrointestinal surgeons. Among the participants were eight of the nine directors, or the representatives of those directors, of the accredited graduate programs in Colombia. Also present were five presidents (or their representatives) of scientific associations related to diseases of the digestive tract and eleven former presidents of those associations. Participants included endoscopy professors and other professors and directors of endoscopy institutes and well known opinion leaders.

83% of participants were male and 17% female, 80% were over 40 years of age, 63% had practiced their professions for over 20 years, and 13% had practiced their professions between 15 and 20 years.

The research group consisted of three people with MAs in Education and a research assistant. They designed the study and its implementation, systematization, and analysis and also wrote the paper.

Information Collection Techniques

The Wideband Delphi estimation method was used (1, 6). This technique allows formulations of recommendations based on achievement of majority agreement or consensus from the expressions of opinions.

The two main variables or dimensions defined in the general work were a formative and an ethic dimension. This article presents the consensus reached with regard to the ethical variable.

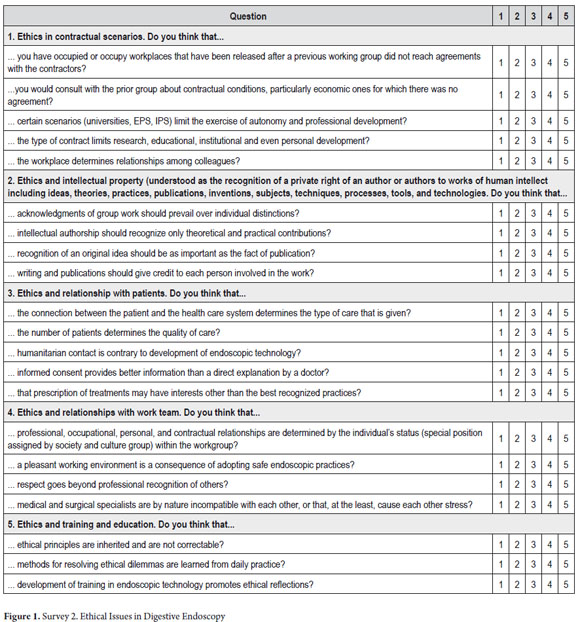

Survey No. 2 shown in Figure 1 was developed from 21 statements of dilemmas which were distributed to five groups according to the following secondary variables (or categories):

- Contractual scenarios.

- Intellectual property.

- Relationships with patients.

- Relations with the staff.

- Training in ethics

Each question was evaluated according to a 1-5 Likert scale in which 1 meant âStrongly Disagree,â 2 meant âDisagree,â 3 meant âNeutralâ (neither agree nor disagree), 4 meant âAgree,â and 5 meant âStrongly Agree.â

We conducted the survey in two stages. The first stage was a pilot survey of 8 gastroenterologists who belong to the Colombian Association of Digestive Endoscopy (ACED). They responded to the survey independently and privately. After their forms were completely filled out a discussion was held about the clarity, relevance and intentionality of each survey question. Based on those remarks, appropriate adjustments were made to the final survey used to obtain the consensus.

For the second stage, the 34 participants were distributed at four round tables. Each table had a chairperson and secretary and an advisor from the research group. The phases of the consensus were explained. They consisted of presentation of the problem, first release of individually written questionnaire answers, second release of the survey for group discussion, explanation of each group's consensus to the other participants, discussion at each table, and then the final vote on the questionnaire which was followed by a private computer based individual exercise (7).

ANALYSIS METHODOLOGY

Quantitative analysis using descriptive statistics focused on determining percentages. Consensus was defined as 75% or more of the final individual and private vote. Three groups defining the consensus were established: the sum of the percentages of those who bly agreed and those who agreed, the sum of the percentages of those who bly disagreed and those who disagreed, and a third group consisting of the percentage obtained from those who checked neutral (neither agree nor disagree).

Qualitative analysis with the content analysis method was used to analyze the audio recordings of the round table discussions. The focus of the analysis was guided by the categories defined and discussed previously (8).

Ethical issues

Participants were informed of the objectives of the consensus and research, and especially of the confidentiality with which the data would be handled. Written permission for audio and video recordings of all sessions including roundtables and general meetings of the whole group was requested to demonstrate consent. These records are securely stored.

RESULTS

The following presentation is organized according to major and minor categories. It uses a graphic summation of percentages obtained. Results that expressed consensus (75% or more) are in bold. The main arguments with which agreements were sustained and which supported the qualitative hermeneutic analysis of this study are illustrated with direct quotes from recordings which are presented below the graph.

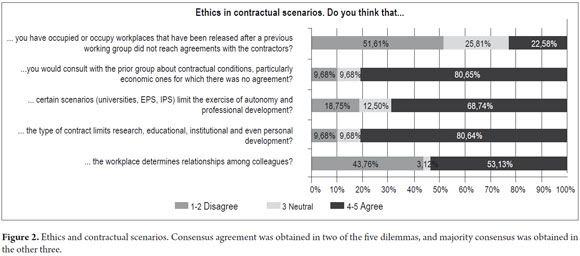

Results from the first category which sought to clarify the actions and considerations of consensus participants when facing dilemmas generated by labor and contractual spaces are presented in the Figure 2.

Consensus agreement (80.65%) was achieved regarding consultation with the prior group that had been replaced at a particular institution. This was true especially under circumstances in which the prior group had not reached an agreement with the employer, â... in any case the previous group should be asked about the reasons, conditions and any special situation for leaving their positions,â but if it is clear that the disagreement between the parties was merely economic, â... to offer one peso less, that would not do...â or â... to offer me less to take a job and then to fire someone else...âwould be to participate in unethical and unfair competition. It would be different from the position in which â... the other person might think that they were paying him or her too little, but I thought I could do the job for that amount... then that's valid ... that's another story...â Consequently, autonomy should be respected here because each professional assigns their own value to her or his work.

It is considered appropriate to know the work environment which will be accessed in depth because â... if an injustice has been done... it should not be supported... if someone is working well, and does things right, I'm not going to replace him or her and solve the administrator's problem (e.g. unfair payment).â

Consensus agreement (80.64%) was also obtained on the third dilemma which asked whether the type of contract limited research, educational, institutional and/or personal development. Majority Agreement (68.74%) was obtained on the fourth dilemma as to whether admission to certain scenarios affected or influenced autonomy and professional development of the specialist who uses endoscopy.

Participants mentioned that, although â...the type of contract, a proactive person can get investigative research done...â it is clear to the majority that in the real scenario â...the contract does limit...especially those who work for EPSs (translator's note: EPSs are similar to HMOs in the USA.)...there are restrictions and no incentives for academic involvement, development of research...or encouragement for innovation or quality...â since everything is focused on providing care. â...one cannot take a moment to look at a journal or discuss cases or anything ...the only thing you only have to do is produce.â

In this way freedoms and possibilities differ depending upon where one works. On one hand, those with ties to a university considered that â...I have never been limited by the university...the university is the place with the least restrictions...â In contrast, â... in an EPS... which should not limit autonomy...in practice they do limit it, directly or indirectly...â Examples include, â...by not accepting a particular treatment or by giving a physician a burdensome number of patients to see every hour... from 2 PM to 7 PM you must see 20 patients with only 20 minutes for each patient...and you consider that it is ethical to take at least 45 minutes per visit...so you either do it in 20 minutes, or you leave...that's what happens today with most health care workers...â

Nevertheless, it is accepted that professional autonomy has limits that go beyond individual activity. In particular, it is understood that the current health care system frames the practice of endoscopy within norms that must be understood and respected. â...autonomy should not be understood as complete freedom: I do what I want, it's my work and it works for me, I don't need a lot of evidence, I do not endorse a protocol .... Contrary to this, â...one should have some control and limits...â the system still needs to, â... have control of expenses, collateral damage, complications, etc....that requires limiting autonomy...we cannot get so far as to be esoteric...what a shame, but if doing what you want is autonomy, then I agree, they must end it. â

Majority agreement (51.61%) was reached about the dilemma of occupying positions after the previous working group had not reached agreement with the contracting party. The discussion was wide to the extent that in these contractual scenarios, âThe maximum limits of ethical values are tested for those who can easily dispense with them...â At any moment different interests may interfere with â...the ethical vision we have of professional practice...â This is especially true when these values have not solidified, for example collegiality because, â...a good relationship between colleagues should prevail over everything else...â In hypotheses such as those posited, the answers vary according to particular contexts. In this sense it would be relevant and valid to learn the reasons for disagreement and withdrawal from a group. In this way it would be unethical to occupy these positions if â...the motives for departure were reasonable...â For example, â...because they are making you do something against the law or ethics...â To the contrary, you should not occupy these positions if the reason for disagreement was institutional pressure in which â...the group resigns because it was obliged to do unethical things...to perform endoscopies with little time for reprocessing...because endoscopy hardware is reused outside of legal standards...or because they demand an exaggerated level of productivity...â The fifth dilemma inquired if the workplace determined relationships between colleagues. The majority (53.13%) disagreed. Although they considered that the space does not create a causal link, it can contribute to positive or negative relationships among colleagues. Nevertheless, it is accepted that, â...the atmosphere at different workplaces is different because there are people who are very hostile... you enter a place where everyone is stressed... by a bad work environment... then it affects you...â But the kind of relationship with medical colleagues should not change, â... work where you work.â Although you should be aware that, â...the way in which you work does affect colleagues working with you...if you are someone who uses foul language, it will affect others... now, if you work in a harmonious way, it will have a positive influence ...â

Along this line of thought some work environments generate little contact among colleagues and their relationships are very political, distant and cold. This is especially true when, â... workloads, administrative requirements, pressure, the need to produce according to indicators...â alienate professionals. Nevertheless, stimulating resent among colleagues is not the only thing such a workplace can do, it can also stimulate appreciation and respect for other colleagues, â...principles that are above those stressful environments ... for one must be a good colleague independent of where you are ... because if my workplace requires me to be bad person, I must leave that place.â

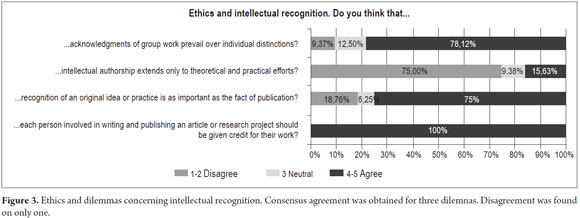

Results from the second category which referred to ethics and dilemmas concerning intellectual recognition are presented in the Figure 3.

The first dilemma inquired whether group work should prevail over individual recognition in professional and intellectual work. Consensus agreement (78.12%) was obtained. For the participants it is important to recognize the role played by all members of a group while maintaining a balance between teamwork and individual work given that when, â...working in a group it must have a leader...but there must be recognition for all members...(to the extent that) each member brings something that is important to the group.â The ideal is â...the recognition of group work and the contributions that each individual makes...which predominates is a value judgment...that must be made within groups...from the inner maturity the group.â

The dilemma about whether each person involved in writing and publishing an article or research project should be given credit for their work resulted in consensus agreement (100%). Participants highlighted the importance of recognizing the individual contributions of each group member such as, â...in some recent articles... (which) show the contribution of each author...â

They specified that, â...international authorship standards require that each person who appears as an author must have contributed (in one way or another)...to the planning, analysis, patient care, checking of the final text, comments on the study...â in a way that reflects the functions internally established by the group and actually showing their, â... contributions to the study (which) must be real and not nominal... in the design, planning and execution of the article and work (beyond administration).â

The dilemma about whether recognition of an original idea or practice is as important as the fact of publication resulted in consensus agreement (75%). The importance of recognizing the original idea carries a face value of honesty regarding who conceived the idea. Nevertheless, the participants highlighted the importance of publishing whenever â... it is the starting point of it all, it is only recognized when it is patented by you... because if, in a lecture, you mentioned an idea, but I took it and developed it for several years. I cannot recognize that...your idea was great, but you didn't start the project, but the idea was yours...â Thus, the participants insisted that when faced with an idea, what you should do is publish it because, â...until it is published, the idea does not exist ... publication is required to crystallize the idea...â

The dilemma about whether intellectual authorship extends only to theoretical and practical efforts resulted in disagreement (75%) because â...there are ideas that are important, not only beyond what is written and what is said...there are ideas and especially practices that are not published, from long ago...that should be recognized as someone's life work.â Thus, there must be a balance between what an idea gives that is embodied in a practice or in a publication because, â...sometimes ideas do not achieve solidity...many practices are works that are permanently under construction (such as a school) ...the complete work of a life that is recognizable by its multiple actions over many years...â

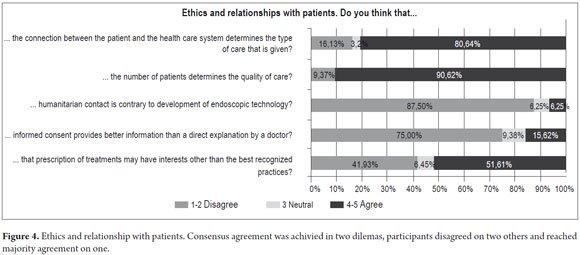

Results for the third category regarding ethical relationships with patients are summarized in the Figure 4.

Consensus agreement (80.64%) was reached on the proposition that the type of relationship the patient has to the health care system determines the type of care that is given. Participants considered that, â...Law 100, the health care system, and intermediaries...have made us look at patients from different modalities differently...frankly care differs between subsidized patients and prepaid patients and patients who cover their own costs...it shouldn't be different...but in quality of care...this is a reality.â

The regulations imposed on the physician by the system in general (and in particular in each of the payment regimes mentioned above) have caused, for example, physicians who perform endoscopic procedures to â...begins to act defensively...or makes a diagnosis...or...a formulation...or a specific procedure ...,â but, according to the type of affiliation the patient has, â...you have to strictly do what you were told to do, since you will be paid accordingly for whatever you do... and you have to do the best you can within that... then the system does affect the type of care that is given...â

This does not mean that there is no awareness of the risks involved in the profession's ethical performance under current conditions in the current Colombian health care system. From this point, participants advocated maintaining principles and core values such as, â...talking to the patient (which) is above all...the reason one cannot work where you cannot talk to the patient.â This basic act of communication is permeated by the ethical value of veracity which can be threatened by facts such as, â...in many places, the doctor does not know the patient's name and still puts a tube inside.â Both patient care and professional practice are affected and, â...fragmented among different agencies and professionals, the patient is sent to a doctor, then to a procedure, then to another procedure, then to another check up, then to another doctor for surgery...â Thus, the regulations, in some scenarios can be so extreme that the perceived risks affect employment, â...if you pass the general over the soldier and you save the soldiers life and not the general's ... the next day you will be fired from the hospital, right?â Undoubtedly, we face ethical dilemmas constantly.

Consensus agreement (90.82%) was achieved for the second dilemma which asked whether the quality of care is affected by the number of patients one is forced to attend. This is consistent with the dilemma discussed above. The demands of the current health care system affect quality of care, not only because of the type of patient affiliation, but also because of, â... many other aspects: type of patient, site conditions, equipment washing times ... I think an endoscopist should do as many procedures as he can do ethically in an orderly way...but institutions are programming a larger number of patients per hour than should be done.â

On this central point, participants considered that there should be a pact on patient care protocols in which â...there should be agreement on the maximum number of procedures per hour...between employers and doctors which takes into account the particular situation...â This pact should also interpret institutional needs since endoscopic practices are not always the same as in university settings where, â...I cannot work in a hurry...and need at least thirty minutes to talk to each patient...â or in scenarios devoted exclusively to patient care in which sometimes, â... protocol limits are surpassed...because time limits are established for a time and then these are violated by the excessive number of patients...the humanitarian concept goes against this ...â

Faced with an inefficient system where, on the one hand, there is a high incidence of digestive cancers which are diagnosed late, and on the other hand there are long delays and lack of timely access to endoscopic health care, many ideas for addressing the serious dilemma of health care were heard and widely debated. Examples include a reference to continued acceptance of performance of gastrointestinal endoscopy by specialists with only one year of training, â...facing our reality ... I prefer a 90% well done endoscopy rather than an endoscopy that is delayed for 180 days.â

Most participants disagreed (87.5%) with the third dilemma that posited that humanitarian contact with the patient and the technological development of endoscopy inherent in current digestive endoscopy practice are contrary to each other. Contrary to dissociation between these aspects, participants said, â...I would still be close to my patient, I would explain what I am going to do... the best (human and technological) possibility that I have... and I have to say and do all of it...â In this way humanitarian treatment cannot be replaced or overtaken by various technological advances which, however, must serve the welfare, dignity and full respect due the patient. The patient must receive sufficient information about their level of development, scope, limitations, risks and advantages.

The fourth dilemma posited that informed consent forms provide better information than a direct explanation by a doctor. Most participants (75%) disagreed. It was argued that the scope of informed consent, â...may be ethical or legal, but verbal consent is more ethical, while the written word is more legal.â In this sense it was posited that there could be, â...tacit consent that exists when you have a good relationship, one can check it through nurses...it does work like a verbal contract...â Nevertheless, it is accepted that, â... when providing expert testimony in a lawsuit, what matters is what is written and in tangible letters...â

This legal consideration confronts perceptions that, in some cases, â...the patient becomes calmer when the doctors speak to them, but not when they only have the two sheets of paper...one must speak at least two words...â Participants considered that the patient has more clarity when the physician explains each procedure to be carried out in detail. In most cases, â...many patients do not read the agreement, do not get it...and they sign it just because, they don't pay attention to it...(For this reason) in our service, for cholangiography (ERCP) we take the time to explain all possible risks, including death, even by drawing pictures and even if the anesthesiologist is furious.â

This is in accordance with Colombian law in which â...the code of ethics (Article 11 of Law 23 of 1981, Standards of Medical Ethics) says that one should not worry unnecessarily about frightening the patient too much, but at the same time you must explain everything...there should be a balance...(I think) it is easier to get it in spoken language than in writing...that depends on whether the patient can read...(but) here patients do not read, contrary to patients in the USA where they read and are informed.â

It is not to be forgotten that technology allows the use of videos to help patients understand what they need to about the procedure that will be performed. It was also taken into account, that â...the patient should be informed (days prior to the procedure) so that the patient had time to meditate about it at home... and even with a lawyer...â In the same way, the presence of a witness is of great importance when filling out the consent form. It is best that, â...the patient goes with a family member (the closest one they have)... and that he/she also hears that explanation...because when the patient has complications, the ones who will fight for the patient are the family members.â

Participants insisted that verbal and written informed consent should not be considered to be mutually exclusive. Instead, â...practice and medical law say that both methods should be used, it is mandatory to give consent in writing and to explain it before witnesses because what is written is not entirely valid since the patient can then say that she or he did not understand and he was forced to sign something that he or she did not understand...â attempting to override what the specialist assumes.

The last dilemma in this category posited that that prescription of treatments may have interests other than the best recognized practices. This obtained majority agreement (51.61%) with a marked divergence due to the perception of the intervention of the pharmaceutical and medical equipment industries through the support they provide to many gastroenterologists, especially for continuing education activities (usually through attendance at conferences related to the specialty). Nevertheless, it is clear that, â...the welfare of the patient should not be affected by commercial interests, or any interest...doctors should act exclusively to ensure that their only goal is the welfare of the patient, with no distinction of culture or economics...â

Some people perceive that the reality of the relationship with the pharmaceutical industry â...is that it puts pressure on doctors to prescribe...and then they must have the ethics and behavior for doing so...â and there are even times when interests other than continuing education stand out, and these seem to be closer to the profit motive, â... these are threats to ethics...they use very powerful elements like...travel, conferences, personal perks that should not interfere but are threatened...even in the EPSs, for example treatments for non-POS treatment programs...â (Translator's note: POS is a category of government approved and subsidized prescription drugs and procedures.) The understanding that both the interests of the pharmaceutical industry and the ethical framework of professional behavior can go together to the extent that the medical act is never separated from core values that protect the patient and that have to do with, â...the benefit obtained with safety, accuracy, efficiency, effectiveness, equity and opportunity... therefore there is nothing more important than ensuring the values of respect, humanity and dignity of the patient...â

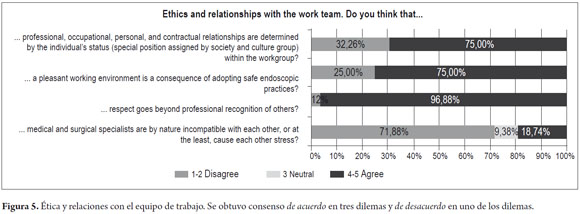

Results for the fourth category regarding ethics and relationships with work team are summarized in the Figure 5.

The first dilemma posited that professional, occupational, personal and contractual relationships were determined by individual status (understood as the particular position assigned by society and culture group) of a person in the group. Consensus agreement (75%) was achieved, although some participants considered that relations, â... with colleagues and nurses and all should be equal...â while others argued that â...types of relationships are determined by status...At the same time as they are conditioned by social and economic relations of friendship or kinship... assigned by society, group and culture...that is a reality of Colombia...not ideal but it is like that...â

The second dilemma postulated that pleasant work environment is a consequence of eligible and safe endoscopic practices. Consensus agreement (75%) was obtained. Some participants see no relationship between work environment and safe practices as in the following statements, â... you can have a very good working environment but do perform very poor endoscopy ... or you can have good practices and a bad work environment...â However, other participants said, â...if you work where there are safe practices, there should be a good atmosphere... because if everyone works under the same conditions, the group will have good results and the work environment will be good...â Contributing to a good working environment is, â...the fact that you know that you have a safe work team which includes the endoscopy unit and that protocols are followed and become the rule... this creates an atmosphere of tranquility...â

In the same way, having good relationships that go beyond the social sphere is markedly important because nothing comes from â...good relations if there is no good practice... this causes misunderstandings very frequently...â because deficiency of professional practice, â...ends up affecting the working environment...this is also a consequence...â A typical example of this is â...some state hospitals that have a spectacular working environment... however, they do not always have the safest conditions for patients... but the work environment is great... because people might need to work with... their nails.â But bad relationships can also have safety implications in professional practice such as, â...some private clinics, where all resources are available but doctors struggle within hostile environments...â that may interfere with fair or good decisions for their patients.

Consensus agreement (96.88%) was obtained for the third dilemma which posited that respect goes beyond professional recognition of others. Arguments supported the general concept of human equality in areas of gender, race and religious beliefs. This concept was placed well above disparities between levels of professional training or the type of discipline each person works in.

A majority (71.88%) disagreed with the proposition of the last dilemma that ancestral differences between clinical gastroenterologists and surgical specialists cause their apparent incompatibility or natural tension. Participants considered that this assessment is, â... a myth that has spread... but of course there is some tension between the two.â

However, it is clear that in some training programs there is clinical exclusivity, so â...I have no problem with surgeons, but I will not let them into our service... our service was created by and for internists...â Nevertheless, some gastroenterology programs with surgical emphasis are aware that, â... surgeons finish the program and (must solve and) work as gastroenterologists without enough clinical gastroenterology training, but they have to handle it...they should receive training from internists...for which reason we send them to hospital shifts with you (the internists)...â

In this sense, we see how groups where there are, â... people from both sides, this strengthens...and generates mutual aid, and has strengthened the group...â Where they share knowledge, they support each other technically and conceptually, so that now there is a tendency to accept the complementary nature of these specialties. This opening promotes another dimension of communication between internists and surgeons which is that, â...respect in interpersonal relationships positively affects both the development of the workplace and collegiality...â This is a greater value than other interests or discrepancies that push colleagues away from each other.

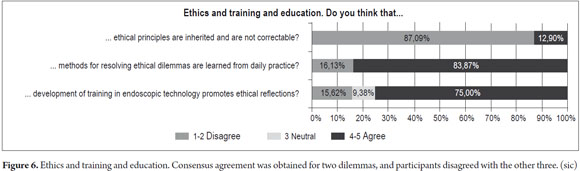

Results for the fifth category regarding ethics and education and training are summarized in the Figure 6.

The first dilemma posited that ethical principles are inherited and cannot be modified. The consensus of participants (87.09%) disagreed with this, although it was stated that, â...there is something that is transmitted from the cradle...there is also the ability to think, reason, change and improve things in the course of life...â while accepting that the human being and his or her experiences allow a person to discern and change her or his attitudes.

In the same way, medical training, practice and consequently ethics which are inherent must be permanent because they help doctors resolve dilemmas and confront situations of conflict. The goals of the medical profession should always be kept in mind, and while this is exercised, ethics must be a constant of the natural evolution of our profession.

On the other hand, the importance of education in values is understood, since â...the teacher teaches students more than endoscopy...the teacher also teaches morals, how to greet colleagues, how to treat patients or the woman serving the coffee...and that is not inherited, it is learned... and is summed up in one word ... formation...â

In the same way, to assume that values and ethical principles cannot be modified contradicts the teaching activity of many gastroenterologists because, â...not having the possibility of modifying the ethical or moral burden that is brought...denies the position of any teacher... (Which) is not easy... just as cholangiography is not easy, but you learn how to do it... so it is the same with ethical problems...â So ethical training cannot be seen as a tangible or obvious teaching in contrast to performance of colonoscopy of which there can be immediate visual verification. Nevertheless, the evidence that ethics and morals are learned is obvious when the endoscopist is faced with a real variable and unpredictable dilemma.

The second dilemma postulated that ethical conflict resolution was learned from daily practice. It obtained consensus agreement (83.87%). Without forgetting that daily practice only provides a fragment of the learning of that resolution, theoretical accuracy of principles and values is essential, so that, â...values must be emphasized to people...it also requires education... relating experience to motivations...showing the meaning of them, coherence and acceptance of true ethical principles... and learning how to apply them ...â In practice, endoscopist do not have the possibility of learning ethics through trial and error, but rather must have maturity and the capacity to make proper and responsible decisions which are always for the benefit of the patient.

The third dilemma posited that development of training in endoscopic technology promotes ethical reflections. This obtained consensus agreement (75%). Since technological development continuously accompanies medical practice, it is a necessity for professionals to constantly upgrade because, â...to the extent that technology advances, the doctor has to have a much more complete and determined criteria of what he will do...technology allows a doctor to choose...â new techniques and indicators which are brought into working and academic contexts. These, â...require that the team produce...then such development promotes the ethical reflection that we also go through in gastroenterology meetings...â New developments and additions create a need to, â...limit their use, and there must be reflection on the ethics of usage...because if there is not, technology could be used in ways that it should not be used...technology does not obligate me... my own values do...if there is no temptation, there will be no reflection...â

Just as the use of new technologies to provide optimal patient treatment is important, a key moral value in the formation of physicians is collegiality with the proposal that, â...one must try to have less ego (I know everything, I have everything, the truth I have, I am the best) to be more ethical, to have more respect for others, to understand human beings...â This constitutes the essence not only of professional behavior, but also of personal behavior.

These new applications demand ethical reflections on patients' safety and welfare. When dealing with, â... a technological development that is not within the reach of our own training, the ethical thing to do is to refrain from this procedure and ask a colleague for a hand...I want to do this...for the welfare of my patient...you don't always have to think of fame or power...or money...you have to think of your patient...what is best for him?â

This brings up the important role of teachers. In particular it brings up fostering of solid pedagogical and ethical training since in several â...college scenarios...specialists (new graduates) automatically become university professors...and have to teach theory...and these boys and girls are forced by circumstances to jump into the role of the surgeon (or endoscopist)...and assume legal responsibility for their actions...and are not even paid for doing so.â This discourages the labor of teaching and affects the formation of new specialists.

DISCUSSION

Participation in a consensus of specialists using endoscopy as a diagnostic and therapeutic tool acquires a special complexity when one of the topics has to do with ethics in professional practice.

Clearly, when invited to reflect on ethical dilemmas, we do not seek to give specific recommendations or solutions but rather to brainstorm and identify options from the context of the experiences of the participants.

For this reason, we invite people with experience in professional practice to this kind of consensus since the approach to the main issue is facilitated by the resolution of their personal cases. Thus, we can achieve better contextualization of a general problem. In this respect, the joint participation of experts in events like this allows us to propose mature ethical decisions that are not in any case silver bullets for solving dilemmas because the way people react to them will always be very difficult (not to mention unpredictable).

The specialist who uses endoscopy (similar to the entire medical community) is then faced with ethical and moral uncertainty when confronted with situations that require a position and that goes beyond scientific issues because these situations also touch upon social or technological areas as can be seen in the dilemmas in this study.

These uncertainties may be caused, in part, by lack of training in ethics which prevents doctor from having a framework that conceptually defines the problem, facilitates understanding, and enables the physician to provide solutions (9).

The definition of ethics varies in different contexts, but parameters of medical ethics have been found and accepted and have become permanent with the passage of time. Now, their general acceptance is universal. These parameters, medical practice and service to health care, have been established as constants which have served as the axis for maintaining the concept of medical ethics for centuries. (9) In this respect, this work looked at three categories which are stable constants: the relationship with patients, relationships in working groups and training in ethics. We also considered several unstable variables that can modify the ethical sense of action and that are related to variable sociopolitical moments such as the law and health care systems oriented by a particular economic view. These variables were behavior in employment scenarios and intellectual property issues.

Ethics and contractual scenarios

Dilemmas that may occur in employment scenarios and contractual relationships involve ethical issues in three intersecting and special value situations: conflict resolution, the right to work and receive payment for services, and collegiality.

Workplace conflicts may be administrative, over remuneration, or about patient care. Operating policies and decisions usually go beyond strictly medical matters and involve doctors who face limited resources or health care guidelines focused on coverage (as mentioned by consensus participants). Physicians should to adopt stances in which principles of medical ethics prevail. In other words they should focus their interests on protecting the patient. It was suggested that disagreements between administrators and doctors should not be vented in front of patients and instead should be dealt with privately and in the following order. First, attempt to find initial solutions as informally as possible by negotiating directly with the staff members with whom you disagree. Second, obtain and respect the opinion of everyone involved. Third, provide a wide range of possible solutions, making it clear to the patient that resources are limited. Finally, respect the final decision of the person who must make that decision or invoke the arbitration if no definite agreement is reached (10).

When disagreement involves firings or resignations, there are various dilemmas to be faced by the person or the group that replaces the person or people who have left. These dilemmas are widely covered by the results. Here we will mention an issue which is central to the decision, payment of professional fees. It is well established that every doctor is entitled to receive fees, since they are â...a payment to the doctor who deserves an honor for his services...â which, to avoid becoming a source of abuse, falls under some guidelines set forth in each society. Considerations that must be taken into account include not charging colleagues fees, respecting well established and agreed rates, not requiring advance payment (â...it is not part of professional decorum...â) (11).

When fees are not charged, it may be considered unethical if what is sought is a political position or advertising which could create an unfair situation for other colleagues who charge fair rates. Similarly, commercialism in the profession is considered to be unethical. This is particularly true if a patient is directed to a particular specialist, laboratory or pharmacy which gives the doctor a percentage of the patient's payment for goods or service. This practice is unfair and violates the patient's autonomy and the rights of other professionals who are not favored. Doctors should not be brokers because they have no legal right to demand payment for services other professionals provide to their patients (11).

To charge fees properly, a doctor must be talented, thoughtful and honorable. Her or his primary consideration should be the health of the patient and the understanding that this compensation is much more valuable than all the money that could be received (11). Independent of the pressures of the modern, globalized world, the medical profession must never lose its altruism. When faced with negotiating a fee, physicians they should act fairly and loyally towards departing colleagues while recognizing that the level of remuneration and working conditions should be compensated with the prestige and status that the individual or group believes they have reached.

The third element that matches these dilemmas has to do with the medical collegiality since being a good colleague is inevitably bound to being a good doctor since both conditions require âgoodâ features, qualities and responsibilities that are the result of a comprehensive education with b family, academic and human foundations. Since becoming is a process, there are no classes that teach how to be a good colleague. The fundamental principles and values being a good colleague might be:

Honesty: what is said and what is done a reflection of the consciousness and thought of the doctor that meets the legal and moral standards of society including of a medical society such as that of gastroenterology.

Respect: the decency and the dignity and of the other permeate all interpersonal relationships.

Benevolence: the continuous search for good physical, mental and social development of the other, or sympathy and goodwill towards the other (12).

These precepts of a good colleague should be reflected in behaviors of loyalty and mutual consideration towards other doctors. It is especially important not to allow the changing characteristics of the health care system and real dilemmas such as those proposed in this study influence the partnership and support among and between colleagues. Nor can we forget to perform other such as teaching respect for reputation and each others' good names, the necessity of an understanding attitude towards medical errors, and professional courtesy (12).

Ethics and intellectual recognition

The first concerns brought up about ethical behavior related to others' intellectual production focused attention on respect for production activities and participation in scientific writing, brainstorming, and project development. In general it was agreed that explicit recognition of each type of contribution (large or small) reflected an ethical act based on the principle of justice and values such as loyalty, honesty, sincerity and respect for the intellect and the person.

Based on this, intellectual property should assess value concerning authorship and order of authorship in research (scientists). Being the first author results in benefits at work, benefits of institutional and professional recognition, and economic benefits. For this reason the first author has been defined as, â...an individual who has taken the most responsibility for the article, usually the one who has the greatest interest in developing a topic...â (13).

Participants also considered it advisable to define other aspects of authorship such as the order of the authors from the outset. This can be done by specifying the responsibilities of each participant that will take part in the research. These responsibilities may change during the process, a change that requires a reflective exercise by the whole team so that it can honestly and fairly recognize work performed. Formats for authorship and co-authoring have been found to facilitate recognition of the work produced by each member of a research team. These proposed formats provide the possibility of objectively changing the initial agreements on rights of authorship and co-authorship at the end of the investigation or manuscript according to the roles and tasks that were actually performed by each person. This depends entirely on the responsibilities undertaken and executed by each and every member of the team and on the ethical values upon which such agreements were reached (13).

An element that was left out of this category has to do with the validity of knowledge and with the epistemology of medical knowledge that is generated by medical research. Much of its cruelest face was shown in the XX century at places like Auschwitz and Dachau where research had no ethical framework to limit it. This lack of control led to the emergence of codes of ethics for biomedical research such as Nuremberg Code, the Declaration of Helsinki and the Good Clinical Practice guidelines of the FDA of 2007. These have established social boundaries, agreed upon principles and values that govern not only personal but also institutional research in areas that can endanger human life and health (14, 15, 16).

Similarly, this study calls on endoscopists to reflect on respect for both individual and intellectual contributions and to monitor ethical principles and values that should be addressed in any research activity. The endoscopist should be critical of the ways knowledge arises from specific investigations since they are the ones who will conduct the clinical practice. It is difficult to predict what may happen in the practice of a professional when the knowledge with which she or he operates has emerged from unethical people or scenarios.

Ethics and relationships with patients

The overall policy framework in medical ethics focuses attention on two perspectives. The first deals with the conduct of the doctor towards the patient. This is called deontology or the application of principles, values, virtues and duties that correspond to what are defined as âinternal goodsâ. The second perspective, makes note of the relationship between biomedical practices, whether clinical or experimental, and individuals and communities. These are relationships in which principles and values that ensure respect for human rights must also be guarded and which are defined as âexternal goodsâ (2, 17).

The principles and values of charity including confidentiality, truthfulness and respect apply to the first perspective related to internal goods whereas the principles and values of âdo not harmâ including solidarity and justice apply to the perspective related to external goods.

Research has shown that the line between the two perspectives tends to become confused or to be erased as the doctor-patient relationship exceeds strict care and approaches biomedical research or enters into work and contractual relationships.

Constraints within the current social security laws in Colombia have had a profound impact on the doctorpatient relationship. Nevertheless, the perspective of some authors who say that this is a perverse inheritance of the twentieth century should not be forgotten. Although we talk about the rights of patients, the model of justice in health care or the right to health in many contexts, these are protected while in fact they are violated in particular conditions such as those mentioned by participants of this consensus (2). Under these conditions general practitioners, and especially gastroenterologists and endoscopists can have the judgments that guide their practices clouded when they forget principles, values and ethical standards that should always be respected.

In the same way that the external circumstances have influenced medical practice, social developments and changes in information technology throughout the world have made patients leave behind the kind of absolute belief in the doctor who knew everything and who could not be questioned. This change has provided momentum for âobtaining informed consentâ as the guiding moral compass of respect for the patient because informed consent tend to give the patient adequate information about their condition. This is especially true in endoscopy because of the need and the obligation to explain to the patient the nature of the procedures to be performed, as well as the risks and benefits which might result and the possible alternatives treatments that might be used (18).

This allows creation of an effective partnership between the doctor and the patient in which the doctor believes that obtaining consent is a very significant form of showing respect for the autonomy and self-determination of the patient. It provides protection against complaints and malpractice lawsuits.

Thus, it is an obligation for the endoscopist to always obtain written consent for performance of any procedure or treatment that involves some risk. The physician must take into account that, if the patient has not received the appropriate information, the patient can argue that she or he has not given consent despite signing the paper. Moreover, we must not forget that studies have come out that suggest that the use of technological tools such as videos are as useful and effective as the presence of the doctor and the video together (19).

Similarly, the question about whether the prescription of treatments including endoscopy has different interests involved other than recognized best practices gave rise to two scenarios for reflection. First, the relationship that doctors may have with the pharmaceutical and medical equipment industries in terms of research, scholarship, support, and sponsorship should not influence diagnostic or therapeutic decisions. These decisions should be guided solely by values that seek the welfare and safety of the patient. On the other hand, by maintaining these values the endoscopist can protect his own principle of autonomy and be able to act justly. An example would be prescribing drugs that are cost accessible to patients which respects the patient's right to improve or heal (20).

Ethics and relations with the work team

The resolution of dilemmas related to the team is covered by values and principles similar to those outlined above, especially those related to contractual scenarios. This is where collaborative work is settled in groups. This is the cornerstone of safe quality digestive endoscopy.

The rules of good collegiality apply to the resolution of misunderstandings between surgeons and clinicians which occur less and less frequently. In general, relationships with other health professionals should be guided by the same principles that govern doctor-patient relationships (11). The reason for this is egalitarian conception is that, while not all health care personnel have the same levels of training and education, what makes all personnel humanly equal is their common concern for the welfare of patients. Thus, two key values must remain in this relationship:

- Non-discrimination. It is not acceptable that a person be separated based on age, ethnicity or race, gender, sexual or political orientation, social class, nationality, illness or disability.

- Respect (as opposed to non-discrimination which can be seen as passive in a relationship) has an active and positive connotation since it reassesses the knowledge and experience of all team members as well as reassessing each of them as a person (12).

These two values should help overcome conditions in which lack of confidence in the ability or integrity of another person (or in the presence of irreconcilable personal conflicts) alters the entire work environment with consequences that can even place patient welfare at risk.

Ethics and training

As mentioned above, difficulties and a sense of ethical uncertainty can be attributed to the lack of specific training in ethics. But it must be borne in mind that the teaching of ethics has special considerations, since it is not an area that can be taught solely in theory nor can the learning of ethics be confirmed by performing a traditional evaluation.

In other words, ethics is not behavior itself but rather a framework for the physician's behavior. Training and education in ethics has to give sufficient weight to the individual aspects of the students including experience, motivation, emotions, his family, religious education and other factors (9).

Other issues that should be considered are social and/or political changes in contemporary society, and family or religious dogmas that may come into direct conflict with scientific principles. Similarly, situations in clinical care that can cloud an endoscopist's thinking seem pertinent to ethical training. This is especially true for high pressure scenarios related to emergency care and to issues of time, dedication to each patient, and financial reward. In a more personal sphere this is true for pressures related to success, failure, prestige and vanity.

At the same time inclusion of medical history is considered to be an important part of ethical training because it allows us to understand fundamental elements in ethical medical practice. Of course, ethical training should include the theoretical basis in the guiding principles of medical ethics which with students will have a conceptual framework to address the dilemmas of daily practice (5, 9).

A key and definitive objective of training in medical ethics is achievement of consistency between what is said (words and ideas), and what is done. This falls into the large space of uncertainty of the teacher who will only see whether the students learned what she or he taught, or wanted to teach, after several years.

CONCLUSIONS

The first Colombian Consensus âAgreement on Fundamentalsâ in the practice of digestive endoscopy has conceptually clarified ethical principles and values related to the resolution of ethical dilemmas found in real scenarios of the practice of endoscopy as shown in Table 1.

At the same time, we propose reflection on a final dilemma of the many dilemmas that have arisen. From this final dilemma approximations involving ethical and moral actions in the specialty medical practice in Colombia a private practice or group can be reached.

Finally, the way the Colombian Association of Digestive Endoscopy conceived and developed this project and its general sense was not intended to standardize the way in which endoscopists behave individually or in groups towards certain dilemmas. Rather it was conceived to invite reflection, â... arouse concern, stimulate critical being, forget the rules and force continuous self examination ... which is not easy ...â (9).

1. Aponte D, Blanco C, Flores N, Forero A, Cañadas R, Peñaloza R, et al. Primer consenso colombiano sobre la práctica de endoscopia digestiva "Acuerdo en lo fundamental" (Primera parte. Aspectos Formativos). Rev Col Gastroenterol 2012; 27(3): 185-198. [ Links ]

2. Vidal M. Las fracturas éticas del modelo globalizado: estándares éticos en la práctica clínica y la investigación biomédica. Universidad El Bosque, Revista Colombiana de Bioética 2010; 5(2): 60-82. [ Links ]

3. Malhotra K, Ottaway CA. Ethical issues in Canadian Gastroenterology: Results of a survey of Canadian gastroenterology trainees. Can J Gastroenterol 2004; 18(5): 315-317. [ Links ]

4. Talento Humano en Salud. Ley 1164 de 2007. Ley Pub. No. 1164 de 2007. Congreso de Colombia; 2007 (Octubre 3 de 2007). [ Links ]

5. Sánchez Torres F. Temas de ética médica; 1995 disponible en URL: http://www.tensiometrovirtual.com/upload/BE012_g.pdf consultado el 10 de septiembre de 2012. [ Links ]

6. Astigarraga, E. Método Delphi. Universidad de Deusto San Sebastián. (citado 1 de Junio de 2012) (s.f.). Disponible en URL: http://www.echalemojo.com/uploadsarchivos/metodo_delphi.pdf. Consultado 01 de junio de 2012. [ Links ]

7. Batarrita J. Entre el consenso y la evidencia científica. Gac Sanit 2005; 19 (1): 65-70 [ Links ]

8. Gil J. Análisis de datos cualitativos. Aplicaciones a la investigación educativa. En "El análisis de datos cualitativos" Aproximación interpretativa al contenido de la información textual. 1994. p. 31-63. [ Links ]

9. Rodríguez A. Utopía o realidad: ¿Tiene sentido enseñar ética médica a los estudiantes de medicina? Anales Médicos Asoc Med Hosp ABC 2000; 45(1): 45-50. [ Links ]

10. William J. Medical Ethic Manual. AMN. El médico y los colegas. Cap. 4. 2005. p. 80-93. [ Links ]

11. López E. Ética médica. Universidad Autónoma de Centro América. Colección Décimo Aniversario. Recuperado 2011; 8: 77-82. [ Links ]

12. Carrillo G. Consideraciones sobre ética y colegaje. Revista Colombiana de Ortopedia y Traumatología 1999; 13(2): 100-104. [ Links ]

13. Acosta A. Cómo definir autoría y orden de autoría en artículos científicos usando criterios cuantitativos. Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias, PUJ 2007; 12(1): 67-81. [ Links ]

14. Asociación Médica Mundial (WMA). Declaración de Helsinki. Disponible en URL: http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/17c.pdf. Consultado 05 de septiembre de 2012. [ Links ]

15. FDA. Normas de Buenas Prácticas Clínicas. 2007; Disponible en URL: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/ Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm073128.pdf. Consultado 07 de septiembre de 2012. [ Links ]

16. Pfeiffer M. Investigación en medicina y derechos humanos. Andamios. 2009; 6(12): 323-345. [ Links ]

17. Torres R. Las dimensiones éticas de la relación médico paciente frente a los esquemas de aseguramiento. Presentación realizada durante el XIII curso OPS/OMS-CIESS legislación de salud: la regulación de la práctica profesional en salud. México, D.F.; 2006. [ Links ]

18. Rodríguez C. Consentimiento informado en endoscopias digestivas: ¿es necesaria una consulta preendoscópica? Publicación cuatrimestral del Master en bioética y derecho 2008; 14: 29-33. [ Links ]

19. Ahuja A, Tandon RK. Ethics in diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopy. En Stanciu C, Ladas S (Eds.). Medical Ethics. Focus on Gastroenterology and Digestive Endoscopy. Beta Medical Arts; 2002. p. 97-108. [ Links ]

20. Ladas SD et al. Second European Symposium on Ethics in Gastroenterology and Digestive Endoscopy. Endoscopy 2007; 39: 556-565. [ Links ]

texto en

texto en