Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Revista colombiana de Gastroenterología

versão impressa ISSN 0120-9957

Rev Col Gastroenterol vol.28 no.3 Bogotá jul./set. 2013

Microbiological profile of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in a Southern Brazilian City

Mariana do Amaral Ferreira, MD. (1), Gabriela Bicca Thiele, MD. (1), Maíra Luciana Marconcini, MD. (1), Esther Buzaglo Dantas-Correa, MD, PhD. (1), Leonardo de Lucca Schiavon, MD, PhD. (1), Janaína Luz Narciso-Schiavon, MD, PhD. (1)

(1) Núcleo de Estudos em Gastroenterologia e Hepatologia (NEGH- Nucleus for Studies in Gastroenterology and Hepatology) at the Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina (UFSC). Florianópolis, Santa Catarina, Brasil.

Received: 07-05-13 Accepted: 26-06-13

Abstract

Introduction: Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), one of the most frequent infectious complications experienced by patients with decompensated cirrhosis and ascites, has a high mortality rate.

Objective: Our objective was to identify the main agents causing SBP at a University Hospital between 2008 and 2011.

Methods: A cross-sectional study of positive results from ascitic fluid cultures was carried out. Clinical and laboratory variables were extracted from the medical records.

Results: 47 patients with positive ascitic fluid cultures were included. Average age was 55.7 years ± 15.5 years, 70.2% were men, and 53.6% of patients presented cirrhosis. All cirrhotic patients presented GASA ≥ 1.1 and mean neutrophil count in the ascitic fluid of 3,260.8 ± 5,122.9 cells. The most frequent germs found were Escherichia coli (25.5%), Klebsiella (14.9%), Enterococcus (8.5%) and Streptococcus (8.5%). No significant differences were observed between cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic patients regarding the prevalence of E.coli (19.2% vs. 33.3%; P=0.270), Klebsiella (19.2% vs. 9.5%; P=0,436), Enterococcus (7.7% vs. 9.5%; P=1.000) or Streptococcus (15.4% vs. 0.0%; P=0.117). The presence of infection by two or more germs was more common among individuals without cirrhosis (11.5% vs. 38.1%; P=0.047).

Conclusion: The microbiological profile of ascitic fluid cultures showed a prevalence of gram-negative bacteria similar to other studies related to spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

Keywords

Hepatic cirrhosis, peritonitis, ascitic fluid.

INTRODUCTION

Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis (SBP) is a frequently occurring infectious complication in patients with decompensated cirrhosis and ascites (1). This disease is characterized by an infection of the ascitic fluid and an intra-abdominal inflammatory focus similar to acute pancreatitis and cholecystitis, but without evidence of a visceral perforation (2-4). SBP normally occurs in the final stage of liver diseases and has a high rate of recurrence, about 70% in one year (5-7). In addition to decompensated cirrhosis there are other factors that predispose for SBP including jaundice, malnutrition, and upper gastrointestinal bleeding (8). Some studies also suggest high in-hospital mortality rates for patients with cirrhosis and ascites (20% to 40%) (9, 10). However, this rate has decreased in the last four decades because of early diagnosis and immediate use of proper antibiotherapy (11).

The criteria for the diagnosis of SBP require paracentesis to collect ascitic fluid for analysis. The bacterial culture test positive and/or the fluid must have a neutrophil count that exceeds 250 cells/mm3 (12). Clinical manifestations are nonspecific. The most frequent signs and symptoms include fever, abdominal pain, hepatic encephalopathy, pain or abrupt abdominal decompression, diarrhea, paralytic ileum and hypothermia. Normally, SBP is suspected when the patient begins to show signs of hepatic encephalopathy or a drastic decrease in renal functioning without any precipitating factor. Approximately 10% of patients with SBP have no signs or symptoms (13-16).

The translocation of bacteria through the intestinal cavity to mesenteric lymph nodes should be the main mechanism for developing bacteremia which precedes SBP manifestations. In individuals with cirrhosis, there are three mechanisms involved in this infection's pathogenesis: deficient local immune response (decline of phagocytic activity by hepatic macrophages), bacterial overgrowth in the intestinal lumen, and functional and structural alterations in the intestinal mucosal barrier (14, 17). Most of the microorganisms responsible for SBP derive from the intestinal flora and are mainly aerobic gram-negative bacteria. Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae are the most frequently isolated agents (18-20). In approximately 25% of the cases, gram-positive bacteria such as Streptococcus and Enterococcus are found. Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most common (21, 22). On the other hand, anaerobic bacteria are never the cause of SBP because of their inability to move on the intestinal mucosa and because of the high levels of oxygen on the gut wall (23).

Based on the above considerations, this study's goals were to identify the microorganisms found in ascitic fluid cultures and to describe the clinical characteristics related to the presence of infections in the ascitic fluid of patients with cirrhosis.

METHODS

Casuistic

A cross-sectional study of positive results from tests for SBP of ascitic fluid cultures in the microbiology laboratory of the Polydoro Ernani de São Thiago University Hospital at the Federal University of Santa Catarina (UFSC) was conducted from January 2008 to December 2011. Patients with data missing from their medical charts were excluded, and only the first culture of those that presented more than one positive result was included.

This study's protocol is in compliance with the ethical rules of the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the UFSC Committee on the Ethics of Research on Human Beings (certificate N. 948).

Methods

Information on all individuals submitted to paracentesis, and had positive results on the ascitic fluid culture, was reviewed. Clinical, demographic, and laboratorial variables were gathered from medical reports. The following variables were examined: age (years), gender, length of stay (days), isolated germs on cultures, positive serologies for HBsAg, anti-HCV, and anti-HIV, creatinine, hemoglobin, platelet count, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (AP), gamma glutamyltransferase (GGT), serum albumin, bilirubin, international normalization ratio (INR) and prothrombin activity (PA). The AST, ALT, FA and GGT hepatic biochemical tests were expressed on times the upper limit of normal (xULN). The other variables were expressed in absolute values. Bilirubin, INR, and creatinine were used to find the MELD (Model for End-stage Liver Disease) (24) on individuals with cirrhosis. Only laboratory tests performed within six months after the development of the culture were included in this study. These cultures were collected and plated at the bedside in vials of blood cultures (BacT/ALERT®, bioMérieux) or collected in dry tubes and plated at the laboratory on Blood Agar, MacConkey Agar and Thioglycollate Broth.

Static Analysis

Continuous variables were described with measures of central tendency and dispersion, while the categorical variables were described in absolute numbers and proportions. Continuous variables were compared using Student's t-test or Mann-Whitney as appropriate, and the categorical variables were assessed using chi-squared test or Fisher exact test, as appropriate. The p values smaller than 0.05 were considered statically significant. All tests were two-tailed and carried out using the Statistical Package for Social Science software, version 17.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Case-by-case examination

From January 2008 to December 2011, 660 ascitic fluid cultures were assessed. Among these 53 (8.03%) were positive for SBP and were evaluated for inclusion in the study. Four cultures were excluded because the medical records were insufficient and two were excluded because of repeated reactive results (Figure 1).

A total of 47 patients with positive ascitic fluid cultures were included. Their mean age was 55.7 years (standard deviation ± 15.5 years). 70.2% were male and 26 patients (55.3%) had cirrhosis.

The most commonly found pathologies among the non-cirrhotic patients were acute appendicitis, dialytic chronic renal failure, and acute cholecystitis.

Among individuals with cirrhosis, the mean MELD score was 16.3 ± 9.3 and the mean SAAG score was 1.6 ± 0.7: all had SAAG ≥ 1.1. Regarding the albumin and the neutrophil count in this group's ascitic fluid, the mean, standard deviation, and median were 0.3 ± 0.2 (0.3) g/dL and 3260.8 ± 5122.9 (892) cells, respectively. No differences were observed when comparing the median of ascitic fluid neutrophils of cirrhotic patients to infections by one or more germs (892.0 vs. 322.5; P= 0.407).

Assessment of patients included according to the diagnosis of cirrhosis

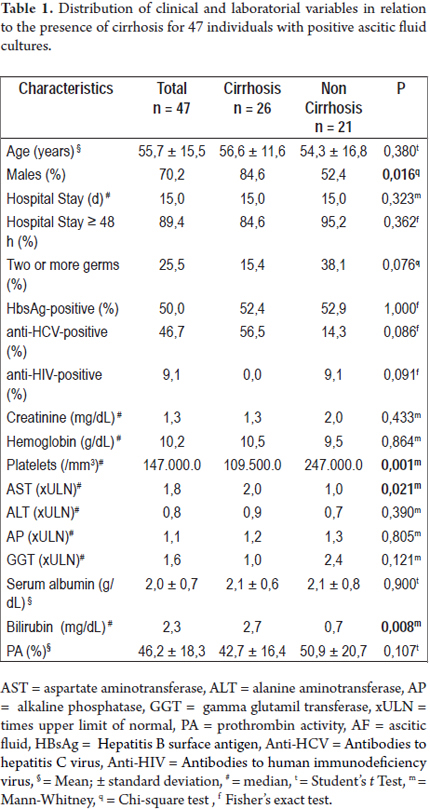

When comparing hepatic cirrhotic patients with others (Table 1), we noted a larger proportion of males (84.6% vs. 52.4%; P = 0.016); larger AST medians (2.0 vs. 1.0 xULN; P = 0.021), higher levels of bilirubin (2.7 vs. 0.7 g/dL; P = 0.008) and smaller platelet medians (1,095,000 vs. 2,470,000 /mm3; P = 0.001). No differences were found in terms of age, length of hospital stay, infection by one or more germs, or for positive results for HBsAg, anti-HCV and anti-HIV. Regarding laboratory variables, no differences were found for creatinine, hemoglobin, platelets, ALT, AP, GGT, albumin and PA values.

Assessment of culture results according to the presence of cirrhosis

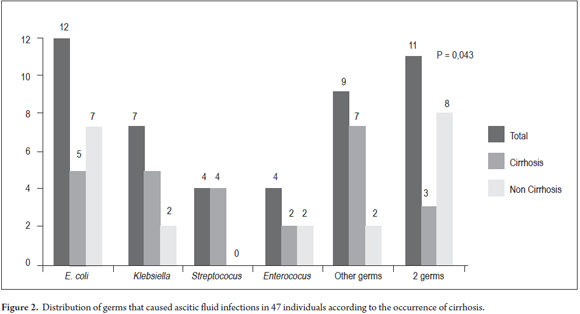

Escherichia coli (25.5%) were the most frequently found germs, followed by Klebsiella (14.9%), Enterococcus (8.5%) and Streptococcus (8.5%). The detailed microbial profile is described in table 2. When comparing the frequency of these germs in the ascitic fluid cultures of cirrhotic patients to other germs (Figure 2), it was impossible to note great differences in the prevalence of E.coli (19.2% vs. 33.3%; P = 0.270), Klebsiella (19.2% vs. 9.5%; P = 0.436), Enterococcus (7.7% vs. 9.5%; P = 1.000) and Streptococcus (15.4% vs. 0.0%; P = 0.117). Infection by two or more germs was most commonly found among individuals without cirrhosis (P = 0.047).

DISCUSSION

The mean age of the individuals suffering from cirrhosis with SBP ranges between 54.3 ± 10 years and 58.3 ± 13.1 years (25-27) which is quite similar to what was found in this study. Nonetheless, lower mean ages ranging between 48.3 ± 1.8 and 49 years-old have been reported by other authors (28, 29). Higher prevalences of males have been reported by several authors. It can vary from 52.3 to 78.2% (25, 29) and has been emphasized in up to 100% of the cases (29).

Due to the reduction of endotoxins and bacteria, liver insufficiency results in greater susceptibility to infections. It can even cause immunosuppression in some patients. Although Shaw et al. have described that SBP is linked to HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) infection in cirrhotic patients (30), in this study none of the patients with cirrhosis and SBP were infected with HIV. Accordingly, it was observed that 9% of the non-cirrhotic patients were HIV positive, possibly because the immunosuppression derived from HIV is a risk factor for infection, regardless of the presence of cirrhosis.

This study shows that patients with cirrhosis and SBP presented liver dysfunction accompanied by low platelet counts, low concentrations of serum albumin, low Pas, high MELD scores, and low albumin concentrations in the ascitic fluid. All of these variables are associated with poor prognoses for patients with cirrhosis (31, 32). It is clear that SBP generally occurs in patients with advanced cirrhosis. The higher the patient's MELD score the greater the risk for developing ascitic fluid infections (33). The mean MELD in this study was 16.3 ± 9.3 for cirrhotic patients which is similar to that of 16.5 ± 5.1 found by Shi et al (27) buy less than the 23.8 ± 8.4 found by Desai et al (26). In this study, low platelet counts were evident. The mean was 129,650.0 ± 97,739.0/mm3 for cirrhotic patients which is higher than those found in other studies in which mean platelet counts ranged from 77,960.0 ± 48,370.0 to 109,000.0 ± 73,000.0/mm3 (27, 34). In this research, the average prothrombin activity in patients with cirrhosis was 42.7 ± 16.4 % which is lower than that of 55.4 ± 14.2 % described by Shi et al (27). Mean serum albumin for patients with cirrhosis ranges from 2.0 ± 0.4 to 2.8 ± 0.3 g/dL (28, 34-36) which is similar to that found in our study. Solá et al. acknowledged the tendency of a higher incidence of SBP in individuals with low protein concentrations in the ascitic fluid (37). The mean of 1.0 ± 0,5 g/dL of proteins in the ascitic fluid that we found in this study is similar to that of 1.2± 1.0 g/dL found by Kim et al (35) The amount of albumin in the ascitic fluid ranges between 0.6 ± 0.3 g/dL and 1.0 ± 1.0 g/dL (35, 25). The mean number of neutrophils in the ascitic fluid among patients with cirrhosis and SBP is compatible with the one described in the literature, with values that vary from 529 to 4,900 cells/mm3 (25, 28, 34, 38).

When using conventional techniques of microbiological diagnosis for SBP, the ascitic fluid culture tests negative in more than 60% of the cases. This is true even in the presence of suggestive clinical manifestations such as fever, abdominal pain, unexplained encephalopathy, acidosis, azotemia, hypotension or hypothermia. This occurs due to deficient culturing techniques. Inoculation of with at least 10mL of ascitic fluid in vials of blood culture at bedside makes it possible to increase chances of obtaining a positive culture test up to 90%. Transporting fluid to the laboratory using nonspecific containers such as syringes or tubes is also a factor that can decrease the sensitivity of the test. In our milieu, we still frequently collect ascitic fluid in a dry tube which might explain in part why only 8% of the ascitic fluid samples test positive for SBP (although the cellularity of the ascitic fluid of these individuals is not known since this fact that was not assessed in this study) (39-41).

In the United States, Desai et al (26) examined 55 patients with SBP and found that 40% of cultures tested positive for SBP with 20% testing positive for gram-negative bacteria and 5.5% testing positive for more than one microorganism. Singh et al (29) assessed 61 individuals with SBP and found that 42 positive cultures tested positive for SBP with 48% testing positive for gram-positive bacteria, and 40% for gram-negative bacteria. Candida species were found in 12% of the cases. With regard to the bacteria found, Escherichia coli was detected in 21.4% of the cultures, Enterococcus faecalis in 16.7%, Streptococcus viridans in 14.3%, Staphylococcus aureus in 11.9%, Klebsiella pneumoniae in 7.1%, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in 4.7%. In addition, one positive case of each of the following germs was found: Streptocococus pneumoniae, Rhodococcus spp., Klebsiella oxytoca, Enterobacter cloacae and Critrobacter freundii.

In Mexico, Bobadilla et al (42) evaluated 31 cases of SBP and found 14 positive cultures and that Escherichia coli was the most common germ (71.4%) followed by Klebsiella pneumoniae (14.2%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (7.1%), Streptococcus faecalis (7.1%) and Serratia marcescens (7.1%). In 13 cases in Barcelona, Solá et al (37) noticed 46.2% with Escherichia coli, 23.1% with Pneumococcus, 15.4% with Klebsiella pneumoniae, 7.7% with Streptococcus viridans and 7.7% with Staphylococcus aureus.

A Pakistani study of 44 individuals with SBP by Kamani et al (34) found that 14.9% had blood cultures that were positive for SBP and 23.5% had positive ascitic fluid cultures of which 72.7% were gram-negative. Escherichia coli was the most commonly found microorganism (61.3%), followed by Streptocococus pneumoniae (11.3%), Pseudomonas species (9.0%), Staphylococcus species (6.8%), Enterococcus species (6.8%), Bacillus species (2.2%) and Group D Streptococcus (2.2%).

In Egypt, Abd Elaal et al (36) evaluated 36 patients with SBP. Among these patients 12 patients had ascitic fluid cultures that were positive for SBP. The most commonly found germs in the study were Escherichia coli (75.0%), Streptococcus faecalis (16.6%), and Klebsiella pneumoniae (8.3%).

A study conducted in the city of Seoul, Korea by Kim et al (35) evaluated 130 patients diagnosed with SBP. Thirty seven (28.5%) had ascitic fluid cultures that tested positive for SBP. The majority of the samples collected were enteric gram-negative Escherichia Coli (62.1%). Other germs were also found, including Aeromonas (13.5%), Streptococcus (10.8%), Klebsiella pneumoniae (8.1%), and Pseudomonas in 5.4% in the positive samples. In another Korean study, Song et al (43) compared the infections in patients' ascitic fluid acquired in the community with those acquired in the hospital. From October 1998 to August 2003, a total of 106 patients whose ascitic fluid cultures had tested positive were studied. They discovered that 32 cases of SBP were caused in-hospital, and 74 were acquired in the community. Gram-negative bacilli, such as Escherichia coli, predominated in both the community and in-hospital group. In 58.5% of the total samples, Escherichia coli were detected as the agent causing the SBP. Klebsiella Pneumoniae was the cause in 11.3% of the cases. Germs, such as Streptococcus pneumoniae (7.5%), others species of Streptococcus (7.5%), Enterococco (5.6%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (1.9%), Acinetobacter baumanii (5.6%) and Aeromonas hydrophila (1.9%) were also isolated.

In a study conducted from June 1987 to April 1991 in the Dutch city of Rotterdam, Siersema et al (38) compared the two methods most often used for culturing ascitic fluid: vials of blood culture and the conventional culturing method. In this period, 31 suspect cases of SBP were diagnosed in 28 patients. Employing the conventional culturing method, the samples of ascitic fluid showed positive results for 11 of the 31 cases of SBP (35%) as against 26 positive results from the 31 cases (84%) by using the vials for blood cultures. Every sample in which there was no bacterial growth using the conventional method also had no bacterial growth when the blood culture method was used. From 26 positive cultures, gram-negative bacilli were detected in 17 cases (65%) and the gram-positive cocci were detected in 9 cases (35%). The same study isolated Escherichia coli in 38.5% of cultures, Klebsiella Pneumoniae in 7.7%, Pseudomonas aeruginosa in 7.7%, Enterobacter cloacae in 3.8%, Acinetobacter sp. in 3.8%, unspecified Gram-negative bacteria in 3.8%, Streptococcus Alpha-hemolytic sp. in 7.7%, Enterococcus faecalis in 7.7%, Streptococcus pneumonia in 11.5%, Staphylococcus aureus in 3.8% and Staphylococcus epidermidis in 3.8% of the cases.

In France, Dupeyron et al (44) assessed a total of 240 cases of SBP over a 20 year period of time from April 1977 to April 1997. The study analyzed changes in the microbiological profile of the agents that cause SBP. At the end of the study, the majority of the ascitic fluid infections were caused by enterobacteria, with no significant change in the percentage between that in the initial period and that at the end of the study. The prevalence of Escherichia Coli was noted in 43.3% of the cases. Other bacteria found included Klebsiella pneumoniae (10%), Groupe D Estreptococcus (7.6%), Enterococcus faecalis (6.7%), Serratia marcescens (4.6%), Staphylococcus aureus (4.6%), Enterobacter cloacae (2.5%), Streptococcus pneumoniae (3.3%), Streptococcus (2.6%), Streptococcus pneumoniae (3.3%), among other agents. We also found in smaller quantity germs such as: Morganella morganii (0.8%), Citrobacter freundii (0.8%), Providencia stuarttii (0.4%), Pseudomonas aeroginosa (1.3%), Streptococcus pyogenes(0.8%) Streptococcus agalatiae (0.8%), Enterococcus avium (0.4%), Enterococcus faecium (0.4%), Staphyloccocus coagulase negativo (2.9%), Listeria monocytogenes (0.8%), Bacterioides (2.1%), Clostridium (1.7%), Candida albicans (0.4%), Candida glabrata (0.4%), Fusobacterium (0.4%), and Aerococcus viridans (0.4%).

A study conducted in São Paulo by Reginato et al (25) looked at 219 patients who had been diagnosed with SBP. Among them were 123 individuals who had had their ascitic fluids cultured. Sixty-three of them (33.8%) had positive culture results. The microbiological profile enumerated 31.7% Escherichia coli, 7.9% Streptococcus pneumoniae, 7.9% Staphylococcus aureus and 7.9% Klebsiella pneumoniae. In the state of Rio Grande do Sul Almeida et al (45) retrospectively evaluated cirrhotic individuals with SBP whose cultures ascitic fluids tested positive for SBP during two distinct periods: 1997-1998 and 2002-2003. In the first period (1997-1998) 33 cases were included. Three of them (9 %) had polymicrobial infections. The most frequent bacteria were Escherichia coli (13 patients, 36.1%), Coagulase negative Staphylococci in (6 patients, 16.7%), Klebsiella pneumoniae (5 patients, 13.9%), Staphylococcus aureus (4 patients, 11.1%) and Streptococcus faecalis (3 patients, 8.3%). From 2002 to 2003, there were 43 cases, and two (5.0 %) of them had polymicrobial infections. The most frequent bacteria were Coagulase negative Staphylococci in 16 patients (35.6%), Staphylococcus aureus in 8 (17.8%), Escherichia coli in 7 (15.6%) and Klebsiella pneumoniae in 3 patients (6.7%). There was a modification in the bacterial population that caused spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in the two periods analyzed. There was a predominance of gram-negative bacteria in the first period and a predominance of gram-positive bacteria in the second period.

In addition to suggesting contamination, the ascitic fluid cultures that were positive for more than one germ may suggest peritonitis secondary to intestinal perforation. For diagnostic elucidation of these cases, evaluations with imaging tests are indicated. In this study, three cirrhotic individuals presented SBP as the result of infections with two germs, but secondary peritonitis was not confirmed in either case (46).

The samples of individuals with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis observed in this study exhibit characteristics similar to those described in the literature. This is true not only in relation to clinical characteristics, but also to hepatic functions and microbial profiles of the ascitic fluid. There was a high prevalence of enterobacteria which reflects the overall characteristics.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Acknowledgments

This paper was presented as a requirement for obtaining a Medical Doctor's (MD) degree from Federal University of Santa Catarina.

Financial disclosure

Nothing to report.

REFERENCES

1. Garcia-Tsao G. Bacterial infections in cirrhosis: treatment and prophylaxis. J Hepatol 2005; 42: 85-92. [ Links ]

2. Berg RD. Mechanisms promoting bacterial translocation from the gastrointestinal tract. Adv Exp Med Biol 1999; 473: 11-30. [ Links ]

3. Guarner C, Soriano G. Bacterial translocation and its consequences in patients with cirrhosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005; 17: 27-31. [ Links ]

4. Moore K. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis SBP. En Warrel DA, et al. Oxford Textbook of Medicine, 4th Edition, Oxford University Press, Vol 2. Sections 11-17; 2003. p. 739-41. [ Links ]

5. Runyon BA. Management of adult patients with ascites caused by cirrhosis. Hepatology 1998; 27: 264-72. [ Links ]

6. Navasa M, Rodes J. Management of ascites in the patient with portal hypertension with emphasis on spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Semin Gastrointest Dis 1997; 8: 200-9. [ Links ]

7. Guarner C, Sorian G. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Semin Liver Dis 1997; 1: 203-17. [ Links ]

8. Arroyo V, Ginès P, Gerbes AL, Dudley FJ, Gentilini P, Laffig G, et al. Definition and diagnosis criteria of refractory ascites and hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. Hepatology 1996; 23: 164-75. [ Links ]

9. Sort P, Navasa M, Arroyo V, Aldeguer X, Planas R, Ruiz-del-Arbol L, et al. Effect of intravenous albumin on renal impairment and mortality in patients with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. N Engl J Med 1999; 341: 403-9. [ Links ]

10. Toledo C, Salmeron JM, Rimola A, Navasa M, Arroyo V, Llach J, Ginès A, Ginès P, Rodés J. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhosis: Predictive factors of infection resolution and survival in patients treated with cefotaxime. Hepatology 1993; 17: 251-7. [ Links ]

11. Genuit T, Napolitano L. Peritonitis and abdominal sepsis. E Medicine; 2004. [ Links ]

12. Hoefs JC, Canawati HN, Sapico FL, Hopkins RR, Weiner J, Montgomerie JZ. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Hepatology 1982; 2: 399-407. [ Links ]

13. Levison ME, Bush LM. Peritonitis and intraperitoneal abscesses. En Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 6th Edition, Elsevier, Churchill Livingstone, Philadelphia; 2005. p. 927- 51. [ Links ]

14. Such J, Runyon BA. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Clin Infect Dis 1998; 27: 669-74. [ Links ]

15. Parsi MA, Atreja A, Zein NN. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: recent data on incidence and treatment. Cleve Clin J Med 2004; 71: 565-69. [ Links ]

16. Angeloni S, Leboffe C, Parente A, Venditti M, Giordano A, Merli M, Riggio O. Efficacy of current guidelines for the treatment of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in the clinical practice. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14: 2757-62. [ Links ]

17. Guarner C, Soriano G. Bacterial translocation and its consequences in patients with cirrhosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005; 17: 27-31. [ Links ]

18. Runyon BA. Management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis. Hepatology 2004; 39: 841-56. [ Links ]

19. Wiest R, Garcia-Tsao G. Bacterial translocation in cirrhosis. Hepatology 2005; 41: 422-33. [ Links ]

20. Strauss E, Caly WR. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2003; 36(6): 711-7. [ Links ]

21. Ginès P, Cárdenas A, Arroyo V, Rodés J. Management of cirrhosis and ascites. N Engl J Med 2004; 350: 1646-54. [ Links ]

22. Thalheimer U, Triantos CK, Samonakis DN, Patch D, Burroughs AK. Infection, coagulation and variceal bleeding in cirrhosis. Recent Advances in Clinical Practice Gut 2005; 54: 556-63. [ Links ]

23. Fernández J, Navasa J, Colmenero J, et al. Bacterial infections in cirrhosis: epidemiological changes with invasive procedures and norfloxacin prophylaxis. Hepatology 2002; 35: 140-8. [ Links ]

24. Kamath PS, Wiesner RH, Malinchoc M, et al. A model to predict survival in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology 2001; 33: 464-470. [ Links ]

25. Reginato TJ, Oliveira MJ, Moreira LC, Lamanna A, Acencio MM, Antonangelo L. Characteristics of ascitic fluid from patients with suspected spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in emergency units at a tertiary hospital. Sao Paulo Med J 2011; 129: 315-9. [ Links ]

26. Desai AP, Reau N, Reddy KG, Te HS, Mohanty S, Satoskar R, Devoss A, Jensen D. Persistent spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: a common complication in patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and a high score in the model for end-stage liver disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2012; 5: 275-83. [ Links ]

27. Shi KQ, Fan YC, Ying L, Lin XF, Song M, Li LF, Yu XY, Chen YP, Zheng MH. Risk stratification of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhosis with ascites based on classification and regression tree analysis. Mol Biol Rep 2012; 39: 6161-9. [ Links ]

28. Mohan P, Venkataraman J. Prevalence and risk factors for unsuspected spontaneous ascitic fluid infection in cirrhotics undergoing therapeutic paracentesis in an outpatient clinic. Indian J Gastroenterol 2011; 30: 221-4. [ Links ]

29. Singh N, Wagener MM, Gayowski T. Changing epidemiology and predictors of mortality in patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis at a liver transplant unit. Clin Microbiol Infect 2003; 9: 531-7. [ Links ]

30. Shaw E, Castellote J, Santín M, Xiol X, Euba G, Gudiol C, Lopez C, Ariza X, Gudiol F. Clinical features and outcome of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in HIV-infected cirrhotic patients: a case-control study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2006; 25: 291-298. [ Links ]

31. Deschenes M, Villeneuve JP. Risk factors for the development of bacterial infections in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol 1999; 94: 2193-7. [ Links ]

32. Runyon BA. Low-protein-concentration ascitic fluid is predisposed to spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology 1986; 91: 1343-6. [ Links ]

33. Obstein KL, Campbell MS., Reddy KR, Yang YX. Association between model for end- stage liver disease and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2007; 102: 2732-6. [ Links ]

34. Kamani L, Mumtaz K, Ahmed US, Ali AW, Jafri W. Outcomes in culture positive and culture negative ascitic fluid infection in patients with viral cirrhosis: cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol 2008; 8: 59. [ Links ]

35. Kim SU, Chon YE, Lee CK, Park JY, Kim do Y, Han KH, Chon CY, Kim S, Jung KS, Ahn SH. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in patients with hepatitis B virus-related liver cirrhosis: community-acquired versus nosocomial. Yonsei Med J 2012; 53: 328-36. [ Links ]

36. Abd Elaal MM, Zaghloul SG, Bakr HG, Ashour MA, Abdel-Aziz-El-Hady H, Khalifa NA, Amr GE. Evaluation of different therapeutic approaches for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Arab J Gastroenterol 2012; 13: 65-70. [ Links ]

37. Solà R, Andreu M, Coll S, Vila MC, Oliver MI, Arroyo V. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients treated using paracentesis or diuretics: results of a randomized study. Hepatology 1995; 21: 340-4. [ Links ]

38. Siersema PD, de Marie S, van Zeijl JH, Bac DJ, Wilson JH. Blood culture bottles are superior to lysis-centrifugation tubes for bacteriological diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. J Clin Microbiol 1992; 30: 667-9. [ Links ]

39. Rimola A, Garcia-Tsao G, Navasa M, Piddock LJ, Planas R, Bernard B, Inadomi JM. Diagnosis, treatment and prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: a consensus document. J Hepatol 2000; 32: 142-53. [ Links ]

40. Castellote J, López C, Gornals J, Tremosa G, Fariña ER, Baliellas C, Domingo A, Xiol X. Rapid diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis by use of reagent strips. Hepatology 2003; 37: 893-6. [ Links ]

41. Runyon BA. Strips and tubes: refining the diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Hepatology 2003; 37: 745-7. [ Links ]

42. Bobadilla M, Sifuentes J, Garcia-Tsao G. Improved method for bacteriological diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. J Clin. Microbiol 1989; 27: 2145-7. [ Links ]

43. Song JY, Jung SJ, Park CW, Sohn JW, Kim WJ, Kim MJ, Cheong HJ. Prognostic significance of infection acquisition sites in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: nosocomial versus community acquired. J Korean Med Sci 2006; 2 1: 666-71. [ Links ]

44. Dupeyron C, Campillo B, Mangeney N, Richardet JP, Leluan G. Changes in nature and antibiotic resistance of bacteria causing peritonitis in cirrhotic patients over a 20 year period. J Clin Pathol 1998; 51: 614-6. [ Links ]

45. Almeida PR, Camargo NS, Arenz M, Tovo CV, Galperim B, Behar P. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: impact of microbiological changes. Arq Gastroenterol 2007; 44: 68-72. [ Links ]

46. Akriviadis EA, Runyon BA. The value of an algorithm in differentiating spontaneous from secondary bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology 1990; 98: 127-33. [ Links ]

texto em

texto em