Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista colombiana de Gastroenterología

versión impresa ISSN 0120-9957

Rev Col Gastroenterol vol.30 no.3 Bogotá jul./sep. 2015

Update on Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis

Andrea Holguín Cardona (1), Juan José Hurtado Guerra (1), Juan Carlos Restrepo Gutiérrez MD. (2)

(1) Final year medical student at the Universidad de Antioquia in Medellín, Colombia.

(2) Member of the Hepatology Unit and Liver Transplant Program at the Hospital Pablo Tobón Uribe and the Universidad de Antioquia, Tenured Professor in the School of Medicine, Chief of the Gastrohepatology Section, Chief of the Graduate Clinical Hepatology Program, Member of the Gastrohepatology Group in the Faculty of Medicine, at the Universidad de Antioquia in Medellín, Colombia.

Received: 24-09-14 Accepted: 21-07-15

Abstract

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) is a serious complication that occurs among cirrhotic patients with ascites. It is a major cause of the high rates of mortality among these patients and has high rates of recurrence. Early diagnosis and optimal treatment can result in considerable improvements. It is noteworthy that high rates of prevalence of SBP have even been documented in asymptomatic patients. Primary and secondary prophylaxis are of great significance for improving patients chances of survival and for decreasing the initial incidence and recurrence of SBP. Nevertheless, treatment must be applied with great rigor and patients must be monitored carefully to prevent the development of antibiotic resistance. Some of determinants for treatment with antibiotics are previous episode(s) of SBP, digestive tract, evidence of hepatic dysfunction, low concentrations of proteins in ascetic fluid and hyperbilirubinemia. This updates is based on a review of the medical literature about SBP published in both Spanish and English over the last five years and available in major biomedical databases (PubMed, ClinicalKey, EBSCO, Scielo, Scopus and OVID). Our review revealed that there are very few publications in Colombia and the rest of Latin America and Colombia, some of which were written by the authors and their workgroup.

Keywords

Peritonitis, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, bacterial translocation, cirrhosis, ascites.

DEFINITION

Although Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis had been reported earlier, SBP was first defined by Dr. Harold O. Connen in 1964 who identified it as an infection of the peritoneal fluid with no obvious source within the abdomen that is liable to surgical treatment (1-3). SPB is diagnosed when a culture is positive for ascites and there is a high count of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN).

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Worldwide, bacterial infections occur in 25% to 30% of cirrhotic patients and are responsible for 30% to 50% of the mortality in patients with chronic liver disease (4, 5). In Latin America, the prevalence is similar: it ranges from 11.1% to 37.1% with mortality figures ranging from 21.9% to 32% (6-8). A study conducted in Colombia more than 20 years ago documented SPB prevalence at 27.2% with a mortality rate of 27.3% (9).

At one year of follow up of cirrhotic patients with ascites, the incidence of SBP is 10% to 25%. When routine diagnostic paracentesis is done on asymptomatic cirrhotic patients who have ascites at the time of admission to hospital, the incidence of SBP is 10% to 27% (10). In addition, the prevalence of SBP in asymptomatic cirrhotic patients in outpatient settings is 1.5% to 3.5% (11, 12). Bacterascites is found in 1.9% of these patients, but this figure rises to 11% among hospitalized patients (12, 13).

In the first descriptions of SBP, it was associated with mortality rates that could be as high as 90%, but this situation has improved considerably. Now the mortality rate is about 20% in standard scenarios (12, 14, 15). Still, hospitalized patients who are clinically decompensated have a probability of death during the first episode of SBP ranging from 10% to 50% (16, 17). This situation is attributed to acute deterioration of liver functioning more than to sepsis than itself which is responsible for only one third of these deaths (17).

After the first episode of SBP, the mortality rate within the next year is 70%, and the mortality rate in the second year is 80% (10). About 70% of SPB cases occur in patients with advanced cirrhosis (Child-Pugh Stage C) (10). In addition, recurrence rates a year after a first episode of SBP are as high as 40% to 70% (10, 18, 19).

SBP is considered to have been acquired during hospitalization when symptoms occur 72 hours after admission. In these cases, the infection is considered to be an independent risk factor for hospital mortality. Within 30 days of diagnosis, the mortality rate can be as high as 58.7% compared to a 30-day mortality rate of 37.3% for infections acquired in the community (20).

PATHOGENESIS

Initially the term "spontaneous" was used because the cause of the infection was not clearly identifiable (1). Over time it has been partially clarified (18, 21-23).

Many factors contribute to the pathogenesis of SBP. One of them is bacterial translocation that consists of passage of bacteria from the intestinal lumen to mesenteric lymph nodes. This process is favored by three main factors: bacterial overgrowth, alteration of the intestinal mucosal, and impaired local and systemic immunity (24-27). Bacterial overgrowth itself is favored by the impaired motility of the small intestine (28, 29) and functional changes in the intestinal mucosa are explained by increased permeability (30, 31).

The low concentration of hydrochloric acid produced by the use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) in cirrhotic patients is another factor. Some studies have found that patients who have cirrhosis and who are using PPIs have three times the risk of cirrhotic patients who do not use PPIs of developing SBP (OR 4.23, 95% CI: 1.82- 2.77) (32).

Studies have shown that bacterial translocation increases in cirrhotic patients (33-35) because of reduced local immunity that prevents bacterial clearance so that the bacteria is able to infect the mesenteric lymph nodes from where they can circulate systemically causing bacteremia (36). More frequent and longer lasting bacteremia occurs in cirrhotic patients because of their immunosuppressed states which are principally due to hypoalbuminemia and because of portosystemic shunts with alter the functioning of the mononuclear phagocyte system (10, 36, 37).

DIAGNOSIS

The most common symptoms are fever (68%), altered mental states (61%), abdominal pain (46%), gastrointestinal bleeding, chills, nausea and emesis (12). Nevertheless, it should be remembered that up to 30% of patients with SBP are completely asymptomatic (10, 14, 38). For this reason, all cirrhotic patients with ascites who are admitted to the hospital should undergo diagnostic paracentesis to remove ascitic fluid regardless of their clinical condition (4, 11). Fluid should be cultured for aerobic and anaerobic bacteria and Gram stained (although it has been reported to have a sensitivity of only 10%, it has a specificity of 97.5%) (39). Total and differential cell counts should be done. Cytochemistry should measure LDH, albumin, glucose, amylase and bilirubin (If indicated by observation of dark or yellow-brown color.) (40). As far as possible, ascites fluid must be sampled before the start of antibiotics except when the patient is in a septic shock in which case antibiotics should be started within 45 minutes (41).

SBP diagnosis is based on analysis of ascitic fluid (42, 43). A neutrophil count over 250/mm3 is sufficient to diagnose SBP regardless of the outcome of the culture. Cultures will be negative in 40% to 60% of cases according to the worldwide literature which is consistent with Latin American reports ranging from 26.9 and 59% (6, 44, 45). In contrast, negative culture reports from Colombia are as high as 78%. (46) This may be due both to the small number of bacteria in the inoculum (usually <1 bacterial cell/mL) and to the presence of confounding factors (13). Since these may include start of antibiotics prior to diagnostic paracentesis and/or poor technique in administration of antibiotics the same, it has been suggested that samples for culturing be bottled at the bedside when there is high clinical suspicion and negative cultures (10, 11, 47-50).

In addition, it has been reported that only half of patients with SBP presented positive blood cultures (2), and there are even studies in which positive blood cultures are reported in only in 25% of patients (9). Some have suggested taking 500 neutrophils/mm3 as the cutoff point for diagnosis. This would increase specificity at the expense of sensitivity (11).

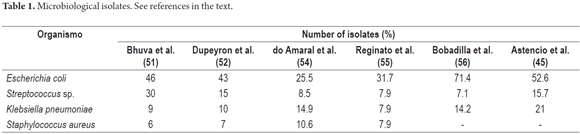

In general, the microorganisms that have been described as causes are, in descending order, E. coli, Klebsiella Pneumoniae, Streptococcus Spp, Enterococcus faecalis, E. faecium, Enterobacter Cloacae and Staphylococcus aureus (Table 1) (13, 45, 50-56).

In Latin America, E. coli isolates are the most common with percentages that range from 25.5% to a 71.4% (45, 54, 56), but there are reports in which up to 54% of cases of SBP are associated with Gram-positive bacteria (6).

A study conducted in Bogotá, Colombia between 2009 and 2013 found that the main microorganism isolated was Escherichia coli. This was treated with ampicillin and sulbactam in 65% of cases of which 39% required changes in treatment (46).

Bacteriascitis is another possible scenario. This occurs when the ascites PMN count is less than 250/mm3 and can be due to a secondary colonization of the ascitic fluid by an extraperitoneal infection. This may be a transient and spontaneously reversible colonization or it may the first stage of SBP (11, 23).

The PMN count varies according to the infecting bacteria: it is lower for patients with SBP due to staphylococcus spp. (87 ± 200 PMN/mm3) than for patients with SBP due to streptococcus spp. ( 650 ± 1359 PMN/ mm3), enterococcus spp. (771 ± 1686 PMN/mm3) and enterobacteriaceae spp. (8342 ± 3275 PMN/mm3) (57).

In patients with hemorrhagic ascites (red blood cell count > 10,000/mm3), one PMN per 250 erythrocytes/mm3 must be subtracted. (4, 40) When lymphocytosis is predominant in ascites, the differential diagnosis should include tubercular peritonitis, neoplasms, congestive heart failure, pancreatitis and myxedema. In general, this condition is not related to SBP (4, 5, 11, 38).

Other methods have been used to diagnose SBP. Reactive strips have a sensitivity ranging from 45% to 100%, a specificity ranging from 81% to 100% and a negative predictive value over 95% in most studies. This makes it a suboptimal diagnostic method. Measuring lactoferrin in the ascites fluid has a sensitivity of 96% and specificity of 97% with a cutoff point ≥242 ng/mL. Measuring serum procalcitonin (PCT) has a reported sensitivity of 86% to 95% and a specificity of 79% to 80%. Other markers previously used include pH and lactate in ascites but due to doubtful diagnoses have fallen into disuse (4, 13, 58-61). The picture for use of real-time PCR is not very encouraging. One study found bacterial DNA in 92% of the cultures that were positive for SBP and in 53% of the cultures that were negative for SBP. More than this, in most cases RT-PCR could not identify the bacterial strain. There was also disagreement between the bacteria identified by culturing and amplification techniques in this study, and RT-PCR was positive in 60% of cirrhotic patients with sterile ascites (62-64).

Cirrhotic patients have higher levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) than the general population and when infection occurs, the more severe the underlying liver dysfunction, the lower the increase in CRP. However, the constant monitoring of CRP concentrations can help determine the patient's response to antibiotic therapy (35, 65-68).

It is essential to distinguish whether or not peritonitis is secondary to a source that is susceptible surgical treatment (48). This is important because surgical treatment increases survival rates when peritonitis is secondary, but surgery decreases survival rates for SPB (21, 48, 69). Secondary bacterial peritonitis is the cause of 5% to 10% of all peritonitis in cirrhotic patients with ascites. It should be suspected when there is inadequate response to treatment, when multiple microorganisms are isolated in a culture from ascites and when we have at least two of the Runyon criteria: glucose <50 mg/dL, total protein>1 g/dL, and LDH> 225 mU/mL (4).

The Runyon criteria have high sensitivity (97%) but low specificity (56%), therefore other criteria have been proposed for this differential diagnosis. They include measurement of carcinoembryonic antigen and alkaline phosphatase in peritoneal fluid. When carcinoembryonic antigen levels are over 5 ng/mL, it indicates secondary bacterial peritonitis. Similarly, alkaline phosphatase levels in peritoneal fluid over 240 U/L indicate secondary bacterial peritonitis, respectively. Reported sensitivity is 92% and reported specificity is 88% (70).

TREATMENT

Given that culture results can take 24 to 48 hours, antibiotic therapy should be started without waiting, but, as far as possible, after taking samples (10, 11). Thus, antibiotic therapy is started empirically according to the literature published on SBP and especially to the local microbiological profile.

A 2011-2013 study by the Germen group in Medellin found the following profiles of bacterial resistance in different hospital departments (Table 2) (71).

In general, the first-line antibiotics are third-generation cephalosporins (44, 72), except for treating SBP acquired during hospitalization which is mainly associated with enterococcus faecium and enterobacteriaceae spp. which produce extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) in which case carbapenems or tigecycline is indicated (11, 20, 73, 74).

Among the cephalosporins, the use of two grams of IV cefotaxime every 12 hours is preferred since it is associated with good concentrations in the peritoneal fluid (75-77). Ceftriaxone, but has proven to be less effective than cefotaxime. It is considered an alternative, but the fact that it has the possibility of inducing (ESBL) should be noted (78). Other options include amoxicillin with clavulanic acid (2) and fluoroquinolones including norfloxacin and ofloxacin (11). The latter should not be used in patients who have received prophylaxis for SBP using a drug from the same pharmacological group (11). Treatment should be continued until the PMN count in the ascites is below 250/mm3. On the average this occurs within five to ten days (74, 79, 80).

Therapeutic response should always be assessed in all patients through clinical follow-up and control paracentesis 48 hours after antibiotic therapy begins (81). It is considered that treatment has failed if the clinical picture worsens, when PMN in ascites increases, and when PMN decreases less than expected (less than 25% of the initial value of PMN at 48 hours after starting antibiotic treatment) (79). Treatment failures may be due misdiagnosis of secondary bacterial peritonitis or to resistant microorganisms (11, 48). Conversely, if the patient has improved during this monitoring period, oral administration of an antibiotic such as 400 mg ofloxacin every 12 hours can be used instead of IV or nasal-gastric tube administration (4, 5, 10, 37, 40, 44, 76, 82).

ANTIBIOTIC PROPHYLAXIS

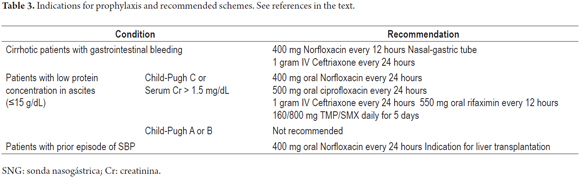

Because of the costs involved and the potential for development of bacterial resistance, antibiotic prophylaxis should be considered only for patients who are at high risk of developing SBP (Table 3). Bacterial resistance is increasing. In the case of quinolone, resistance has been documented in up to 50% of Gram-negative bacteria isolated from patients who have received prophylaxis with norfloxacin as opposed to in only 16% of those who did not receive prophylaxis. In the case of TPM/SMX, resistance has been documented in samples from 44% of patients who are treated while it has been found in only 16% of those who are not (72, 83).

The following list shows factors considered high risks for development of SBP (44, 84):

Patients with cirrhosis who have gastrointestinal bleeding have 25% to 65% probability of developing a bacterial infection including pneumonia, urinary tract infections and/or SBP within seven days. An additional infection in one of these patients increases the risk of rebleeding (4). In this patient group, 400 mg every 12 hours of oral norfloxacin or one gram of IV ceftriaxone IV every 24 hours is recommended as antibiotic prophylaxis depending on the severity of cirrhosis and on whether or not the patient has previously received quinolone prophylactically (11, 78, 85).

Patients with impaired liver and/or kidney function who have protein concentrations of less than 15 g/dL in ascites are also at risk. Antibiotic prophylaxis with 400 mg of norfloxacin every 24 hours has been shown to reduce the risk of SBP and hepatorenal syndrome at one year, and to increase survival rates at three months and one year, for these patients (4). Other antibiotics such as rifaximin have been tried without conclusive results (17, 86). Antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended for patients with low protein concentrations in ascites but with mild to moderate liver disease (11).

Patients with a prior episode of SBP have a recurrence rate of 70% in the first year. Treatment with 400 mg of norfloxacin every 24 has been demonstrated to decrease this rate to 20% (11). Intermittent antibiotic prophylaxis has been suggested, but this could quickly select more resistant flora, so it should be avoided (4). It should also be noted that, due to SBP's high mortality and recurrence rates, one episode is an indication for liver transplantation (11, 38, 44, 79, 87, 88). Prophylaxis should be continued until completion or disappearance of ascites (81).

HEPATORENAL SYNDROME

The incidence of type I hepatorenal syndrome in patients with SBP is around 30%. Renal dysfunction defined as serum creatinine over 1.5 mg/dL is the most important independent predictor of mortality. Among patients with type I hepatorenal syndrome the mortality rate is 67% compared to 11% in patients with normal renal functioning (89). These outcomes are independent of whether or not the infection is resolved.

This phenomenon has been mainly attributed to the accumulation of cytokines and nitric oxide (NO) in the plasma and ascites and to the amplified proinflammatory response which worsens circulatory dysfunction in cirrhotic patients and subsequently leads to renal hypoperfusion (90, 91).

The use of intravenous albumin to prevent hepatorenal syndrome has been studied. Doses of 1.5 g/kg at diagnosis followed by 1 g/kg at 72 hours have reduced incidence to 10%. Similarly, the addition of albumin to antibiotic therapy has led to a decrease in the mortality rate from 29% to 10% (11, 92). The principal use of albumin has been observed in patients with total bilirubin over four mg/dL and serum creatinine over one mg/dL. It has reduced both the mortality rate and the incidence of hepatorenal syndrome (91, 93).

KEY ISSUES

- SBP is one of the most feared complications in cirrhotic patients because of its high rate of recurrence and high mortality rate. It should be suspected in all cirrhotic patients with ascites, and especially if accompanied by fever, abdominal pain, encephalopathy and impaired hepatic and/or renal function. The most important measure is early diagnosis and prompt treatment.

- Diagnosis: ≥250 neutrophils/mm3. Also cell chemistry, Gram stain, and culture of ascites are required.

- Treatment starts immediately after sampling: Two g IV Cefotaxime every 12 hours for 8 days unless nosocomial infection is suspected, in which case treatment should be one g IV Meropenem every 8 hours.

- Bacteriascitis: <250 neutrophils/mm3, culture of ascitic fluid tests positive. Manage like SBP.

- Prophylaxis: 400 mg oral norfloxacin every 24 hours:

- For patients with previous episode of SBP

- For patients with gastrointestinal bleeding administration through a nasa-gastric tube every 12 hours is recommended.

- For patients with Child-Pugh C cirrhosis with ascites protein less than 5 g/dL)

- SBP is a criterion for liver transplantation since transplantation resolves the acute situation and the patient is stabilized.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Sustainability Project of the Vice-Rector for Research at the University of Antioquia.

REFERENCES

1. Conn HO. Spontaneous peritonitis and bacteremia in laennecs cirrhosis caused by enteric organisms. a relatively common but rarely recognized syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1964;60:568-80. [ Links ]

2. Garcia-Tsao G. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: A historical perspective. J Hepatol. 2004;41(4):522-7. [ Links ]

3. Guarner C, Runyon BA. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Gastroenterologist. 1995;3(4):311-28. [ Links ]

4. Pleguezuelo M, Benitez JM, Jurado J, Montero JL, De la Mata M. Diagnosis and management of bacterial infections in decompensated cirrhosis. World J Hepatol. 2013;5(1):16-25. [ Links ]

5. Runyon BA. Management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis: An update. Hepatology. 2009;49(6):2087-107. [ Links ]

6. Mathurin Lasave SA, Agüero López AP, Spanevello Petrin VA, Chapelet Cisi AG. Prevalencia, aspectos clínicos y pronóstico de la peritonitis bacteriana espontánea en un hospital general. Rev Cubana Med. 2008;47:0. [ Links ]

7. Coral G, de Mattos AA, Damo DF, Viégas AC. Prevalence and prognosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Experience in patients from a general hospital in Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil (1991-2000). Arq Gastroenterol. 2002;39(3):158-62. [ Links ]

8. Garzón M, Granados C, Martínez J, Rey M, Molano J, Guevara L, et al. Ascitis cirrótica y sus complicaciones en un hospital de referencia departamental. Rev Col Gastroenterol. 2004;19:86-93. [ Links ]

9. Restrepo JC, Toro JM, Murillo ML, Maya LM, Leyva J, Correa G, et al. Peritonitis bacteriana espontánea: estudio en pacientes cirróticos descompensados con ascitis. Iatreia Rev Med Universidad de Antioquia. 1995;8:7. [ Links ]

10. Alaniz C, Regal RE. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: A review of treatment options. P t. 2009;34(4):204-10. [ Links ]

11. EASL clinical practice guidelines on the management of ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2010;53(3):397-417. [ Links ]

12. Evans LT, Kim WR, Poterucha JJ, Kamath PS. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in asymptomatic outpatients with cirrhotic ascites. Hepatology. 2003;37(4):897-901. [ Links ]

13. Lippi G, Danese E, Cervellin G, Montagnana M. Laboratory diagnostics of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Clin Chim Acta. 2014;430:164-70. [ Links ]

14. Jain P. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: Few additional points. World J Gastroentero: WJG. 2009;15(45):5754-5. [ Links ]

15. Cejudo-Martin P, Ros J, Navasa M, Fernandez J, Fernandez-Varo G, Ruiz-del-Arbol L, et al. Increased production of vascular endothelial growth factor in peritoneal macrophages of cirrhotic patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Hepatology. 2001;34(3):487-93. [ Links ]

16. Oladimeji AA, Temi AP, Adekunle AE, Taiwo RH, Ayokunle DS. Prevalence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in liver cirrhosis with ascites. Pan Afr Med J. 2013;15:128. [ Links ]

17. Hanouneh MA, Hanouneh IA, Hashash JG, Law R, Esfeh JM, Lopez R, et al. The role of rifaximin in the primary prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in patients with liver cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46(8):709-15. [ Links ]

18. Gonzalez Alonso R, Gonzalez Garcia M, Albillos Martinez A. Physiopathology of bacterial translocation and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhosis. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;30(2):78-84. [ Links ]

19. Tito L, Rimola A, Gines P, Llach J, Arroyo V, Rodes J. Recurrence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhosis: Frequency and predictive factors. Hepatology. 1988;8(1):27-31. [ Links ]

20. Cheong HS, Kang CI, Lee JA, Moon SY, Joung MK, Chung DR, et al. Clinical significance and outcome of nosocomial acquisition of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in patients with liver cirrhosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(9):1230-6. [ Links ]

21. Runyon BA, Hoefs JC. Ascitic fluid analysis in the differentiation of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis from gastrointestinal tract perforation into ascitic fluid. Hepatology. 1984;4(3):447-50. [ Links ]

22. Pelletier G, Lesur G, Ink O, Hagege H, Attali P, Buffet C, et al. Asymptomatic bacterascites: Is it spontaneous bacterial peritonitis? Hepatology. 1991;14(1):112-5. [ Links ]

23. Runyon BA. Monomicrobial nonneutrocytic bacterascites: A variant of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Hepatology. 1990;12(4 Pt 1):710-5. [ Links ]

24. Runyon BA, Squier S, Borzio M. Translocation of gut bacteria in rats with cirrhosis to mesenteric lymph nodes partially explains the pathogenesis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. J Hepatol. 1994;21(5):792-6. [ Links ]

25. Guarner C, Runyon BA, Young S, Heck M, Sheikh MY. Intestinal bacterial overgrowth and bacterial translocation in cirrhotic rats with ascites. J Hepatol. 1997;26(6):1372-8. [ Links ]

26. Runyon BA. Early events in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gut. 2004;53(6):782-4. [ Links ]

27. Sheer TA, Runyon BA. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Dig Dis. 2005;23(1):39-46. [ Links ]

28. Madrid AM, Cumsille F, Defilippi C. Altered small bowel motility in patients with liver cirrhosis depends on severity of liver disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42(4):738-42. [ Links ]

29. Perez-Paramo M, Munoz J, Albillos A, Freile I, Portero F, Santos M, et al. Effect of propranolol on the factors promoting bacterial translocation in cirrhotic rats with ascites. Hepatology. 2000;31(1):43-8. [ Links ]

30. Scarpellini E, Valenza V, Gabrielli M, Lauritano EC, Perotti G, Merra G, et al. Intestinal permeability in cirrhotic patients with and without spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: Is the ring closed? Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(2):323-7. [ Links ]

31. Ersoz G, Aydin A, Erdem S, Yuksel D, Akarca U, Kumanlioglu K. Intestinal permeability in liver cirrhosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11(4):409-12. [ Links ]

32. Bajaj JS, Zadvornova Y, Heuman DM, Hafeezullah M, Hoffmann RG, Sanyal AJ, et al. Association of proton pump inhibitor therapy with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients with ascites. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(5):1130-4. [ Links ]

33. Casafont F, Sanchez E, Martin L, Aguero J, Romero FP. Influence of malnutrition on the prevalence of bacterial translocation and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in experimental cirrhosis in rats. Hepatology. 1997;25(6):1334-7. [ Links ]

34. Cirera I, Bauer TM, Navasa M, Vila J, Grande L, Taura P, et al. Bacterial translocation of enteric organisms in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2001;34(1):32-7. [ Links ]

35. Wiest R, Garcia-Tsao G. Bacterial translocation (BT) in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2005;41(3):422-33. [ Links ]

36. Gonzalez Alonso R, Gonzalez Garcia M, Albillos Martinez A. Physiopathology of bacterial translocation and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhosis. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;30(2):78-84. [ Links ]

37. Fica C. A. Diagnóstico, manejo y prevención de infecciones en pacientes con cirrosis hepática. Rev Chil Infecto. 2005;22:63-74. [ Links ]

38. Moore KP, Aithal GP. Guidelines on the management of ascites in cirrhosis. Gut. 2006;55(Suppl 6):vi1-vi12. [ Links ]

39. Chinnock B, Fox C, Hendey GW. Grams stain of peritoneal fluid is rarely helpful in the evaluation of the ascites patient. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54(1):78-82. [ Links ]

40. National Guideline C. Management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis: Update 2012 [2/18/2014]. Rockville MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Available from: http://www.guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=45103. [ Links ]

41. Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, Annane D, Gerlach H, Opal SM, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock, 2012. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39(2):165-228. [ Links ]

42. Nunez Martinez O, Merino Rodriguez B, Diaz Sanchez A, Matilla Pena A, Clemente Ricote G. Optimization of ascitic fluid culture in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;34(5):315-21. [ Links ]

43. Runyon BA, Montano AA, Akriviadis EA, Antillon MR, Irving MA, McHutchison JG. The serum-ascites albumin gradient is superior to the exudate-transudate concept in the differential diagnosis of ascites. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117(3):215-20. [ Links ]

44. Navasa M, Casafont F, Clemente G, Guarner C, Mata Mdl, Planas R, et al. Consenso sobre peritonitis bacteriana espontánea en la cirrosis hepática: diagnóstico, tratamiento y profilaxis. Gastroentero Hepato. 2001;24(1):37-46. [ Links ]

45. Astencio Rodríguez G, Espinosa Rivera F, Sainz López SM, Castro Caballero K, Pomares Pérez YM. Peritonitis bacteriana espontánea en el paciente con cirrosis hepática. Rev Cubana Med. 2010;49:248-362. [ Links ]

46. Salinas Gómez DC. Caracterización clínica, citoquímica y microbiológica de pacientes cirróticos con peritonitis bacteriana en la Fundación Cardioinfantil. 2014. [ Links ]

47. Runyon BA, Canawati Hn Fau - Akriviadis EA, Akriviadis EA. Optimization of ascitic fluid culture technique. (0016-5085 (Print)). [ Links ]

48. Akriviadis EA, Runyon BA. Utility of an algorithm in differentiating spontaneous from secondary bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology. 1990;98(1):127-33. [ Links ]

49. Hoefs JC. Serum protein concentration and portal pressure determine the ascitic fluid protein concentration in patients with chronic liver disease. J Lab Clin Med. 1983;102(2):260-73. [ Links ]

50. Rubinstein Aguñín P, Bagattini JC. Aspectos microbiológicos de interés en el diagnóstico de la peritonitis bacteriana espontánea del paciente con cirrosis hepática. Rev Med Uruguay. 2002;18:225-9. [ Links ]

51. Bhuva M, Ganger D, Jensen D. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: An update on evaluation, management, and prevention. Am J Med. 1994;97(2):169-75. [ Links ]

52. Dupeyron C, Campillo B, Mangeney N, Richardet JP, Leluan G. Changes in nature and antibiotic resistance of bacteria causing peritonitis in cirrhotic patients over a 20 year period. J Clin Pathol. 1998;51(8):614-6. [ Links ]

53. Ho H, Zuckerman MJ, Ho TK, Guerra LG, Verghese A, Casner PR. Prevalence of associated infections in community-acquired spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91(4):735-42. [ Links ]

54. do Amaral Ferreira M, Bicca Thiele G, Marconcini ML, Buzaglo Dantas-Correa E, de Lucca Schiavon L, Narciso-Schiavon JL. Perfil microbiológico de la peritonitis bacteriana espontánea en una ciudad del sur de Brasil. Rev Col Gastroentero. 2013;28:191-8. [ Links ]

55. Reginato TJ, Oliveira MJ, Moreira LC, Lamanna A, Acencio MM, Antonangelo L. Characteristics of ascitic fluid from patients with suspected spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in emergency units at a tertiary hospital. Sao Paulo Med J. 2011;129(5):315-9. [ Links ]

56. Bobadilla M, Sifuentes J, Garcia-Tsao G. Improved method for bacteriological diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27(10):2145-7. [ Links ]

57. Campillo B, Richardet JP, Kheo T, Dupeyron C. Nosocomial spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and bacteremia in cirrhotic patients: Impact of isolate type on prognosis and characteristics of infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35(1):1-10. [ Links ]

58. Angeloni S, Nicolini G, Merli M, Nicolao F, Pinto G, Aronne T, et al. Validation of automated blood cell counter for the determination of polymorphonuclear cell count in the ascitic fluid of cirrhotic patients with or without spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(8):1844-8. [ Links ]

59. Parsi MA, Saadeh SN, Zein NN, Davis GL, Lopez R, Boone J, et al. Ascitic fluid lactoferrin for diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(3):803-7. [ Links ]

60. Nousbaum JB, Cadranel JF, Nahon P, Khac EN, Moreau R, Thevenot T, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the Multistix 8 SG reagent strip in diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Hepatology. 2007;45(5):1275-81. [ Links ]

61. Viallon A, Zeni F, Pouzet V, Lambert C, Quenet S, Aubert G, et al. Serum and ascitic procalcitonin levels in cirrhotic patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: Diagnostic value and relationship to pro-inflammatory cytokines. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26(8):1082-8. [ Links ]

62. Soriano G, Esparcia O, Montemayor M, Guarner-Argente C, Pericas R, Torras X, et al. Bacterial DNA in the diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33(2):275-84. [ Links ]

63. Zapater P, Frances R, Gonzalez-Navajas JM, de la Hoz MA, Moreu R, Pascual S, et al. Serum and ascitic fluid bacterial DNA: A new independent prognostic factor in noninfected patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2008;48(6):1924-31. [ Links ]

64. Such J, Frances R, Munoz C, Zapater P, Casellas JA, Cifuentes A, et al. Detection and identification of bacterial DNA in patients with cirrhosis and culture-negative, nonneutrocytic ascites. Hepatology. 2002;36(1):135-41. [ Links ]

65. Pieri G, Agarwal B, Burroughs AK. C-reactive protein and bacterial infection in cirrhosis. Ann Gastroenterol. 2014;27(2):113-20. [ Links ]

66. Gabay C, Kushner I. Acute-phase proteins and other systemic responses to inflammation. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(6):448-54. [ Links ]

67. Bota DP, Van Nuffelen M, Zakariah AN, Vincent JL. Serum levels of C-reactive protein and procalcitonin in critically ill patients with cirrhosis of the liver. J Lab Clin Med. 2005;146(6):347-51. [ Links ]

68. Lazzarotto C, Ronsoni MF, Fayad L, Nogueira CL, Bazzo ML, Narciso-Schiavon JL, et al. Acute phase proteins for the diagnosis of bacterial infection and prediction of mortality in acute complications of cirrhosis. Ann Hepatol. 2013;12(4):599-607. [ Links ]

69. Runyon BA. Bacterial peritonitis secondary to a perinephric abscess. Case report and differentiation from spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Am J Med. 1986;80(5):997-8. [ Links ]

70. Wu SS, Lin OS, Chen YY, Hwang KL, Soon MS, Keeffe EB. Ascitic fluid carcinoembryonic antigen and alkaline phosphatase levels for the differentiation of primary from secondary bacterial peritonitis with intestinal perforation. J Hepatol. 2001;34(2):215-21. [ Links ]

71. Germen G. Programa de Vigilancia de Resistencia Bacteriana http://www.grupogermen.org/2013 [cited 2015 06/02/2015]. Available from: http://www.grupogermen.org/. [ Links ]

72. Fernandez J, Navasa M, Gomez J, Colmenero J, Vila J, Arroyo V, et al. Bacterial infections in cirrhosis: epidemiological changes with invasive procedures and norfloxacin prophylaxis. Hepatology. 2002;35(1):140-8. [ Links ]

73. Soares-Weiser K, Paul M, Brezis M, Leibovici L. Evidence based case report. Antibiotic treatment for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. BMJ. 2002;324(7329):100-2. [ Links ]

74. Acevedo JG, Fernandez J, Castro M, Garcia O, de Lope CR, Navasa M, et al. Current Efficacy Of Recommended Empirical Antibiotic Therapy In Patients With Cirrhosis And Bacterial Infection. J Hepato. 2009;50:S5. [ Links ]

75. Such J, Runyon BA. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27(4):669-74; quiz 75-6. [ Links ]

76. Chavez-Tapia NC, Soares-Weiser K, Brezis M, Leibovici L. Antibiotics for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009(1):Cd002232. [ Links ]

77. Felisart J, Rimola A, Arroyo V, Perez-Ayuso RM, Quintero E, Gines P, et al. Cefotaxime is more effective than is ampicillin-tobramycin in cirrhotics with severe infections. Hepatology. 1985;5(3):457-62. [ Links ]

78. Fernandez J, Ruiz del Arbol L, Gomez C, Durandez R, Serradilla R, Guarner C, et al. Norfloxacin versus ceftriaxone in the prophylaxis of infections in patients with advanced cirrhosis and hemorrhage. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(4):1049-56; quiz 285. [ Links ]

79. Rimola A, Garcia-Tsao G, Navasa M, Piddock LJ, Planas R, Bernard B, et al. Diagnosis, treatment and prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: A consensus document. International Ascites Club. J Hepatol. 2000;32(1):142-53. [ Links ]

80. Runyon BA, McHutchison JG, Antillon MR, Akriviadis EA, Montano AA. Short-course versus long-course antibiotic treatment of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. A randomized controlled study of 100 patients. Gastroenterology. 1991;100(6):1737-42. [ Links ]

81. Garcia-Tsao G, Lim JK. Management and treatment of patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension: Recommendations from the Department of Veterans Affairs Hepatitis C Resource Center Program and the National Hepatitis C Program. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(7):1802-29. [ Links ]

82. Fernandez J, Gustot T. Management of bacterial infections in cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2012;56 Suppl 1:S1-12. [ Links ]

83. Tandon P, Delisle A, Topal JE, Garcia-Tsao G. High prevalence of antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections among patients with cirrhosis at a US liver center. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10(11):1291-8. [ Links ]

84. Cohen MJ, Sahar T, Benenson S, Elinav E, Brezis M, Soares-Weiser K. Antibiotic prophylaxis for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients with ascites, without gastro-intestinal bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009(2):Cd004791. [ Links ]

85. Garcia-Tsao G, Bosch J. Management of varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(9):823-32. [ Links ]

86. Lutz P, Parcina M, Bekeredjian-Ding I, Nischalke HD, Nattermann J, Sauerbruch T, et al. Impact of rifaximin on the frequency and characteristics of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in patients with liver cirrhosis and ascites. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e93909. [ Links ]

87. Santos O, Marín J, Muñoz O, Mena A, Guzmán C, Hoyos S, et al. Trasplante hepático en adultos: estado del arte. Rev Col Gastroentero. 2012;27(1):21-31. [ Links ]

88. Altman C, Grange JD, Amiot X, Pelletier G, Lacaine F, Bodin F, et al. Survival after a first episode of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Prognosis of potential candidates for orthotopic liver transplantation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1995;10(1):47-50. [ Links ]

89. Tandon P, Garcia-Tsao G. Renal dysfunction is the most important independent predictor of mortality in cirrhotic patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(3):260-5. [ Links ]

90. Frances R, Munoz C, Zapater P, Uceda F, Gascon I, Pascual S, et al. Bacterial DNA activates cell mediated immune response and nitric oxide overproduction in peritoneal macrophages from patients with cirrhosis and ascites. Gut. 2004;53(6):860-4. [ Links ]

91. Salerno F, Navickis RJ, Wilkes MM. Albumin infusion improves outcomes of patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11(2):123-30.e1. [ Links ]

92. Sort P, Navasa M, Arroyo V, Aldeguer X, Planas R, Ruiz-del-Arbol L, et al. Effect of intravenous albumin on renal impairment and mortality in patients with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(6):403-9. [ Links ]

93. Sigal SH, Stanca CM, Fernandez J, Arroyo V, Navasa M. Restricted use of albumin for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gut. 56. England2007. p. 597-9. [ Links ]

texto en

texto en