Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Revista colombiana de Gastroenterología

versão impressa ISSN 0120-9957

Rev Col Gastroenterol vol.30 no.4 Bogotá out./dez. 2015

The effect of a gluten-free diet on alanine aminotransferase (ALT) in celiac patients

Simone Aiko Hatanaka (1), Natanael de Oliveira e Silva (1), Esther Buzaglo Dantas-Corrêa MD. PhD. (2), Leonardo de Lucca Schiavon MD. PhD. (2), Janaina Luz Narciso-Schiavon MD. PhD.

(1) Medical Student at the Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina (UFSC) in Florianópolis, Santa Catarina, Brazil.

(2) Adjunct Professor in Gastroenterology in the Núcleo de Estudos em Gastroenterologia e Hepatologia (NEGH) at the Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina (UFSC) in Florianópolis, Santa Catarina, Brazil.

Núcleo de Estudos em Gastroenterologia e Hepatologia (NEGH) at the Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina (UFSC) in Santa Catarina, Brazil

Received: 17-07-15 Accepted: 20-10-15

Abstract

Introduction: Celiac disease is an autoimmune disease triggered by ingestion of gluten. It affects approximately 0.5% to 1% of the world population. Extra intestinal manifestations include elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels. Objective: The objective of this study was to evaluate the effects of a gluten-free diet on ALT levels in patients with celiac disease. Methods: This cross-sectional study was conducted in the gastroenterology outpatient clinic of a university hospital. Results: Twenty-six patients with celiac disease were included. Average patient age was 34.1 ± 11.4 years, and 15.4% of the patients were men. Study subjects had a mean ALT level of 54.6 ± 36.3 U/L (median 40.5). There was a higher proportion of individuals with hepatitis B in the group with ALT ≥ 50 U/L than in the group of subjects with ALT < 50 U/L. Among patients tested after treatment with a gluten-free diet, we observed a significant reduction in ALT values (36.0 vs. 31.0 U/L; P = 0.008). Conclusion: Thirty-five percent of celiac disease patients had ALT levels above the upper tertile. Higher ALT levels were found in patients with viral hepatitis B and in those who do not adhere to the diet. There was a reduction of aminotransferases with a gluten-free diet.

Keywords

Transaminases, celiac disease, alanine transaminase, aspartate aminotransferases, diet, gluten-free.

INTRODUCTION

Celiac disease is an autoimmune disorder triggered by dietary gluten. Gluten is a protein complex found in wheat, rye, and barley. Celiac disease is characterized by a chronic inflammatory state of the mucosa of the proximal small intestinal that heals when foods containing gluten are excluded from the diet and returns when these foods are reintroduced (1). The disorder is characterized by a diverse clinical heterogeneity that ranges from asymptomatic to severely symptomatic. It manifests with frank malabsorption, chronic diarrhea, weight loss, and abdominal distention. Other manifestations include iron deficiency with or without anemia, recurrent abdominal pain, aphthous stomatitis, short stature, high aminotransferase levels, chronic fatigue, and reduced bone mineral density (2). Unusual manifestations of celiac disease include dermatitis herpetiformis and gluten ataxia even when there are no gastrointestinal symptoms (3).

Multicenter studies done in Europe and the United States have shown that the prevalence of celiac disease is around 0.5% to 1% (4, 5). Within European populations 0.3% to 2.4% of the people test positive for autoantibodies associated with the disease. It is less common in Germany but more common in Finland (5-7). In São Paulo, the prevalence of celiac disease is 0.6%, which is similar to the rates reported in Portugal and Italy (5, 7, 8).

A positive diagnosis of celiac disease is made by the presence of anti-tissue transglutaminase (tTG) antibodies and endomysial antibodies (EmA) in serologic tests. When positive, they confirm immunologic damage, but a biopsy of the small intestine is necessary to show tissue damage. Histological features include increased intraepithelial lymphocytes, villous atrophy, and crypt hyperplasia (3).

Treatment consists of a gluten-free diet which allows clinical remission and restores antibody negativity. Histological healing occurs 6 to 24 months after the diet has begun (9).

Liver involvement in celiac disease has been studied for more than thirty years, but the impact of celiac disease on several etiologies of liver disease has yet to be determined (10). Two different types of hepatic injuries are often described in association with celiac disease: cryptogenic and damage due to autoimmune liver diseases. Cryptogenic disorders are more common and are typically asymptomatic. They are marked by mild elevation of aminotransferases and are partially reversible with a gluten-free diet (11). In these cases, hepatic histopathology can show nonspecific reactive hepatitis (12). However, there are cases of individuals with celiac disease who have been diagnosed with cryptogenic cirrhosis and portal hypertension of unknown etiologies (13, 14).

Celiac disease has previously been described as related to primary biliary cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, and autoimmune hepatitis in which the hepatic damage is chronic and progressive (11, 15-17). The effect of a gluten-free diet in these situations is controversial (11, 18).

Because there is a lack of information about liver abnormalities related to celiac disease, this study aims to describe the behavior of transaminases in celiac disease, identify factors associated with alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels that are elevated above the superior tertile, and compare the serum levels before and after a gluten-free diet.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted a descriptive, retrospective, and cross-sectional study that evaluated the adult patients with celiac disease. The evaluations of subjects took place in the Gastroenterology Clinic of the University Hospital of the Federal University of Santa Catarina (HU/UFSC) from August 2013 to February 2014. Patients lacking clinical information or laboratory data in their medical records were excluded from this study, as were those who refused to participate.

In a routine medical appointment, individuals were invited to participate in the study. Those who agreed signed an informed consent document in duplicate. Clinical, laboratory, and histological data were then collected from the HU/UFSC medical records service.

Subjects were analyzed according to the following clinical and epidemiological variables: gender, age, family histories of celiac disease, and the presence of diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and anemia.

The laboratory variables were EmA, anti-tTG, hemoglobin, mean corpuscular volume (MCV), red cell distribution width (RDW), and serum iron, ferritin, and albumin. The results of biochemical tests were expressed in absolute values. We used the Dimension® system (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, USA) with Flex reagent (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, USA) at a temperature of 37ºC to analyze ALT and aspartate aminotransferase (AST). The level of ALT is considered to be normal when it is under 78 U/L, and the AST level is considered normal when under 37 U/L. ALT levels were divided into groups by tertiles.

Lifelong gluten-free diets were prescribed for patients with confirmed celiac disease. No other treatment was offered to these patients in this study. ALT was measured before treatment and one year after the initiation of treatment (± 6 months). Screening for celiac disease was done with serologic tests for anti-tTG and EmA (19, 20). We identified EmA with immunofluorescence tests with either rat liver sections or commercially acquired HEp-2 slides. Anti-tTG was detected using a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Quanta Lite, USA). Upper digestive endoscopy and duodenal biopsy were indicated for individuals with positive serology for celiac disease. Duodenal fragments were fixed in 10% formalin, processed with paraffin, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE). Lymphocytic infiltrate, villous atrophy, and crypt hyperplasia were analyzed for diagnoses of celiac disease (1, 20).

Statistical analysis

Patients were evaluated according to ALT levels. A bivariate analysis was conducted to identify factors related to ALT levels above the upper tertile (≥ 50 U/L). Continuous variables were compared using Student's t-test or the Mann-Whitney test, as appropriate. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test. Numerical variables were evaluated before and after treatment using Student's t-test for normal distributions or the Wilcoxon test for non-normal distributions. P values of less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. All tests were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA), version 17.0.

Ethical considerations

The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the review board of the Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina as Study Number 358.045.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the sample

From August 2013 to February 2014, twenty-nine patients with celiac disease and who were being treated in this institution were considered for enrollment. Three patients were excluded due to lack of information about aminotransferases.

Twenty-six patients with celiac disease were included. The mean age was 34.1 ± 11.4 (median 32.0) years, and 15.4% of the patients were men. Clinical features were as follows: 70.8% had abdominal pain, 50.0% had diarrhea, 47.8% had iron deficiency with or without anemia, and one patient had dermatitis herpetiformis. A family history of celiac disease was known for 35% of the patients. EmA values were positive in 72.7% of the patients, and anti-tTG IgA antibodies were positive in 91.3%. No patient had an IgA deficiency. Histologic patterns suggestive of celiac disease were exhibited in 91.67% of the patients. Upper digestive endoscopy and duodenal biopsies were positive in two patients (latent celiac disease).

During the evaluation, seventeen patients (65.4%) followed a gluten-free diet. Of these, there was a reduction of symptoms in 88.2% of the patients, but only 82.3% tested negative for antibodies.

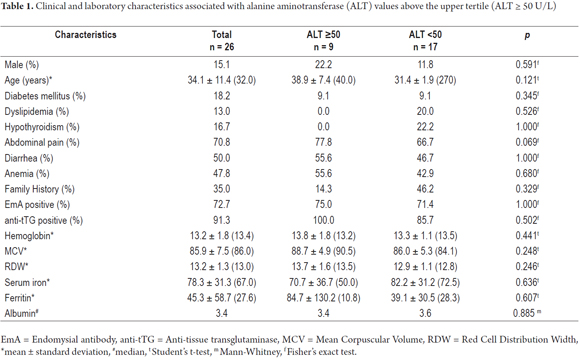

Patients' clinical and laboratory characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The average ALT value was 54.6 ± 36.3 (median 40.5) U/L. Nine patients had ALT values above the upper tertile (ALT ≥ 50). All of the four patients who tested positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) had ALT levels above the upper tertile. Both of the patients who were positive for HBsAg and anti-HBe reactive had low viral loads (< 2,000 IU/L) and were diagnosed as inactive carriers who did not need antivirals. The two other patients who were anti-HBe reactive had high viral loads and advanced fibrosis which characterizes chronic hepatitis due to pre-core hepatitis B virus (HBV) mutants. They were being treated with antivirals: one with tenofovir and the other entecavir.

Comparative analysis of patients above the upper tertile of alanine transaminase with those below the upper tertile

A comparison of patients with ALT ≥ 50 U/L with those with ALT < 50 U/L (Table 1) found a higher proportion of patients with hepatitis B infections in the ALT ≥ 50 group than in the group below the tertile (data not shown). No differences in terms of in gender, age, diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypothyroidism, abdominal pain, diarrhea, anemia, family history of celiac disease, positive EmA, or positive anti-tTG were found between the two groups. Similarly, no differences were observed in hemoglobin, MCV, RDW, iron serum, ferritin, or albumin.

There were higher proportions of individuals in the group with ALT ≥ 50 U/L for:

- Patients who did not adhere to a gluten-free diet (42.9% vs. 93.3; P = 0.021)

- Remission of symptoms (50.0% vs. 100%; P = 0.021)

- Autoantibodies remission (50.0% vs. 91.7%; P = 0.035).

No correlations were observed with ALT, age, weight, hemoglobin, MCV, RDW, iron, ferritin, or albumin.

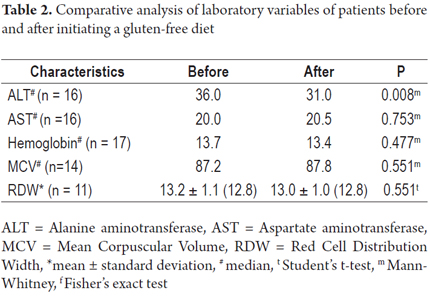

Evaluation of laboratory variables before and after gluten-free diet

Among patients who were tested following treatment of celiac disease, we observed a significant reduction in ALT values after a gluten-free diet (36.0 vs. 31.0 U/L; P = 0.008). No differences in AST, Hb, MCV, or RDW were observed (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Studies of blood donors have been performed in various regions of Brazil to determine the seroprevalence of celiac disease in this country. Based on levels of EmA and anti-tTG, the prevalence of celiac disease in Sao Paulo was 0.6%, and the prevalence in Curitiba was 0.3% (8, 21). In Brasilia, out of 2,045 blood donors, 62 tested positive in gliadin antibody tests and two presented positive EmA (22).

The average age of individuals with celiac disease varies from 32 to 37 years which is similar to the finding in this present study (23-25). Many authors have reported that this disease is most common in females who account for 73% to 80% of all cases (23, 25, 26). However, celiac disease has occasionally been described as being more frequent among men, particularly when evaluations are based on blood banks. This occurs because the majority of blood donors are male (27, 28).

At the time of diagnosis, 34.6% of the patients in this study had ALT levels above the upper tertile (ALT ≥ 50 U/L). Hypertransaminasemia has been found in 9.18% to 40.4% of individuals with celiac disease (23-26, 29). The behavior of ALT in patients with celiac disease following a gluten-free diet has been analyzed in various studies (23-26, 29, 30),{Bardella, 1995, Prevalence of hypertransaminasemia in adult celiac patients and effect of gluten-free diet} but this is the first Brazilian study to evaluate this.

Novacek and colleagues (1999) conducted a retrospective study of 178 patients with celiac disease. AST and/or ALT levels were elevated in 40.4% of these individuals. Following one year on a gluten-free diet, ALT and AST levels were normalized in all but eight cases (4.6%). Four patients were considered to be noncompliant, and the others had hepatic steatosis due to poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, autoimmune liver disease, or alcoholic fatty liver disease (23).

The prevalence of hypertransaminasemia and the effect of a gluten-free diet were evaluated by Bardella and colleagues (1995) in 158 adult celiac patients. At diagnosis, 67 patients (42%) had elevated aspartate and/or alanine transaminase levels (AST mean: 47 IU/L with range 30 to 190; ALT mean: 61 IU/L with range from 25 to 470). At one year, a highly significant improvement in intestinal histology was observed in both groups (P < .0001), and transaminase levels had normalized in 60 individuals (95%). For patients whose ALT remained high, liver biopsies showed fatty infiltration, chronic active hepatitis, chronic infections with either hepatitis B or hepatitis C virus, or an autoimmune condition (25).

Casella and colleagues (2013) studied data from 245 untreated patients with celiac disease and found that 43/245 (17.5%) patients had elevated values of one or both aminotransferases. The elevation was mild (< 5 times the upper reference limit) in 95% and marked (> 10 times the upper reference limit) in the remaining 2 (5%) patients. Following one year on a gluten-free diet, aminotransferase levels normalized in all but four patients who had either hepatitis C infections or primary biliary cirrhosis (26).

Recently, Korpimaki and colleagues (2011) and Moghaddam and colleagues (2013) have evaluated celiac patients and also observed transaminase reductions following a gluten-free diet (29, 30). Although serum transaminase values were within the normal range in the majority of untreated patients in the Korpimaki study, liver enzyme levels initially decreased significantly following initiation of a gluten-free diet (30).

Zanini and colleagues (2013) assessed the factors affecting hypertransaminasemia in 683 patients with celiac disease and 304 with functional syndromes. Hypertransaminasemia was detected in 20%. It was associated with malabsorption and increasing severity of mucosal lesions. Hypertransaminasemia was detected in 7% of the functional gastrointestinal syndrome group and was associated with the World Health Organization's BMI categories. The transaminase level was significantly higher in celiac patients at baseline (25.2 ± 16.9 U/L AST) than in patients with functional syndromes (20.6 ± 9.9 AST, p<0.0001). While following a gluten-free diet, the serum AST levels decreased from 25.2 ± 16.9 U/L at baseline to 19.9 ± 6.6 U/L (P < .0001). A similar effect was observed for ALT (28.1 ± 21.7 vs. 20.4 ± 9.5 U/L, P < .0001), and there was a reduced prevalence of hypertransaminasemia (from 13% to 4%) (24).

As in the studies described above, this study also showed that ALT declined following a gluten-free diet, but the same behavior was not observed with AST. A possible limitation could be the lack of control of factors that affect levels of ALT and AST. These include day of collection, body mass index, physical activity, collection storage, hemolytic anemia, and muscle injuries (31-34). Since this was a retrospective study, ALT and AST levels were not measured at specific times relative to diagnosis or the beginning of the diet. Instead, both aminotransferases were measured in the same collection which reflects the daily basis of clinical care of these patients.

It has been noted in the medical literature that patients with celiac disease and coexisting liver disease from other causes do not show a reduction in ALT levels after beginning a gluten-free diet (25). In this study, a patient with hepatitis B showed a reduction in ALT following a gluten-free diet. This individual had a pre-diet ALT level of 51 U/L and a pre-diet AST level of 26 U/L while post-diet levels fell to 46 U/L and 25 U/L, respectively. There are no similar examples in the medical literature since studies that evaluate aminotransferases before and after a gluten-free diet exclude individuals who are serum positive for hepatitis B which is a confounding factor for hypertransaminasemia. Further studies are necessary to determine whether a gluten-free diet can also improve aminotransferases levels in patients with chronic liver disease.

The mechanism of hepatic injury in individuals with celiac disease is poorly understood. Normalization of serum aminotransferases after following a gluten-free diet suggests a causal relation between gluten ingestion and injuries to the liver and intestine. Patients with hypertransaminasemia have increased intestinal permeability compared to those with normal levels (23). This increased intestinal permeability can lead to augmented absorption of toxins or antigens into portal blood, and this can lead to the hepatic injuries observed in these individuals (35). The fact that tTG is present in the liver and in other tissues besides the intestinal basal membrane suggests the possibility of a pathological role for humoral immunity (anti-tTG) in the hepatic injury observed in those with celiac disease (36).

There are some limitations to this study. It is a retrospective study which includes a limited number of individuals when the high prevalence of European descendants in Southern Brazil and the prevalence of celiac disease in this population are considered. Neverthelss, the University Hospital is a referral center for gastrointestinal disorders and serves individuals throughout the state of Santa Catarina which is one of the smallest states in Brazil.

In addition, the study sample is similar to other samples of patients with celiac disease (37). This reflects the reality observed in our medical practice. The study has a design similar to others that have previously been published although we did not perform liver biopsies on patients to define which individuals presented histological lesions (23, 26, 30). However, since the causal relation between hypertransaminasemia and celiac disease is well known, liver biopsies are currently recommended only for patients in whom aminotransferase levels do not normalize following initiation of a gluten-free diet. There were no individuals in this study who maintained high ALT levels.

A multivariable analysis was not performed, due to the limited number of patients with ALT above the upper tertile (n = 9). Although this is not a rigid rule, most authorities recommend a minimum of ten events per variable when performing logistic regression analysis. This is based on studies that show that fewer than ten events (and especially, fewer than five) lead to an increase in polarization and variability, unreliable confidence-interval coverage, and problems with convergence.

CONCLUSION

Among patients with celiac disease, 34.6% had ALT levels above the upper tertile. Higher ALT levels were found in individuals who did not adhere to a gluten-free diet. Specific studies are needed to establish the mechanism of hepatic damage in celiac patients.

Acknowledgments

This paper was presented as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Medical Doctor (MD) degree from the Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina (UFSC).

Sources of funding

None.

Conflicts of interest

None.

REFERENCES

1. Rostom A, Murray JA, Kagnoff MF. American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute technical review on the diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1981-2002. [ Links ]

2. Fasano A, Berti I, Gerarduzzi T, Not T, Colletti RB, Drago S, Elitsur Y, et al. Prevalence of celiac disease in at-risk and not-at-risk groups in the United States: a large multicenter study. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:286-92. [ Links ]

3. Guandalini S, Assiri A. Celiac disease: a review. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168:272-78. [ Links ]

4. Rubio-Tapia A, Ludvigsson JF, Brantner TL, Murray JA, Everhart JE. The prevalence of celiac disease in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1538-44; quiz 1537, 1545. [ Links ]

5. Mustalahti K, Catassi C, Reunanen A, Fabiani E, Heier M, McMillan S, Murray L, et al. The prevalence of celiac disease in Europe: results of a centralized, international mass screening project. Ann Med. 2010;42:587-95. [ Links ]

6. West J, Logan RF, Hill PG, Lloyd A, Lewis S, Hubbard R, Reader R, et al. Seroprevalence, correlates, and characteristics of undetected coeliac disease in England. Gut. 2003;52:960-5. [ Links ]

7. Antunes H, Abreu I, Nogueiras A, Sá C, Gonçalves C, Cleto P, Garcia F, et al. First determination of the prevalence of celiac disease in a Portuguese population. Acta Med Port. 2006;19:115-20. [ Links ]

8. Alencar ML, Ortiz-Agostinho CL, Nishitokukado L, Damião AO, Abrantes-Lemos CP, Leite AZ, Brito T, et al. Prevalence of celiac disease among blood donors in São Paulo: the most populated city in Brazil. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2012;67:1013-8. [ Links ]

9. Fasano A, Catassi C. Clinical practice. Celiac disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2419-26. [ Links ]

10. Narciso-Schiavon JL, Schiavon LL. Is screening for Celiac Disease Needed in Patients with Liver Disease? International Journal of Celiac Disease 2015;3(3):91-94. [ Links ]

11. Mounajjed T, Oxentenko A, Shmidt E, Smyrk T. The liver in celiac disease: clinical manifestations, histologic features, and response to gluten-free diet in 30 patients. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136:128-37. [ Links ]

12. Volta U, De Franceschi L, Lari F, Molinaro N, Zoli M, Bianchi FB. Coeliac disease hidden by cryptogenic hypertransaminasaemia. Lancet. 1998;352:26-9. [ Links ]

13. Kaukinen K, Halme L, Collin P, Farkkila M, Maki M, Vehmanen P, Partanen J, et al. Celiac disease in patients with severe liver disease: gluten-free diet may reverse hepatic failure. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:881-8. [ Links ]

14. Singh P, Agnihotri A, Jindal G, Sharma PK, Sharma M, Das P, Gupta D, et al. Celiac disease and chronic liver disease: is there a relationship? Indian J Gastroenterol. 2013;32:404-8. [ Links ]

15. Sima H, Hekmatdoost A, Ghaziani T, Alavian SM, Mashayekh A, Zali MR. The prevalence of celiac autoantibodies in hepatitis patients. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;9:157-62. [ Links ]

16. Logan RF, Ferguson A, Finlayson ND, Weir DG. Primary biliary cirrhosis and coeliac disease: an association? Lancet. 1978;1:230-3. [ Links ]

17. Kingham JG, Parker DR. The association between primary biliary cirrhosis and coeliac disease: a study of relative prevalences. Gut. 1998;42:120-2. [ Links ]

18. Volta U. Pathogenesis and clinical significance of liver injury in celiac disease. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2009;36:62-70. [ Links ]

19. Rubio-Tapia A, Murray JA. The liver in celiac disease. Hepatology. 2007;46:1650-58. [ Links ]

20. Green PH, Jabri B. Celiac disease. Annu Rev Med. 2006;57:207-21. [ Links ]

21. Pereira MA, Ortiz-Agostinho CL, Nishitokukado I, Sato MN, Damião AO, Alencar ML, Abrantes-Lemos CP, et al. Prevalence of celiac disease in an urban area of Brazil with predominantly European ancestry. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:6546-50. [ Links ]

22. Gandolfi L, Pratesi R, Cordoba JC, Tauil PL, Gasparin M, Catassi C. Prevalence of celiac disease among blood donors in Brazil. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:689-92. [ Links ]

23. Novacek G, Miehsler W, Wrba F, Ferenci P, Penner E, Vogelsang H. Prevalence and clinical importance of hypertransaminasaemia in coeliac disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:283-88. [ Links ]

24. Zanini B, Baschè R, Ferraresi A, Pigozzi MG, Ricci C, Lanzarotto F, et al. Factors that contribute to hypertransaminasemia in patients with celiac disease or functional gastrointestinal syndromes. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(5):804-10.e2. [ Links ]

25. Bardella MT, Fraquelli M, Quatrini M, Molteni N, Bianchi P, Conte D. Prevalence of hypertransaminasemia in adult celiac patients and effect of gluten-free diet. Hepatology. 1995;22:833-6. [ Links ]

26. Casella G, Antonelli E, Di Bella C, Villanacci V, Fanini L, Baldini V, Bassotti G. Prevalence and causes of abnormal liver function in patients with coeliac disease. Liver Int. 2013;33:1128-31. [ Links ]

27. Kochhar R, Sachdev S, Aggarwal A, Sharma V, Prasad KK, Singh G, Nain CK, et al. Prevalence of coeliac disease in healthy blood donors: a study from north India. Dig Liver Dis 2012;44:530-32. [ Links ]

28. Remes-Troche JM, Ramírez-Iglesias MT, Rubio-Tapia A, Alonso-Ramos A, Velazquez A, Uscanga LF. Celiac disease could be a frequent disease in Mexico: prevalence of tissue transglutaminase antibody in healthy blood donors. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:697-700. [ Links ]

29. Alavi Moghaddam M, Rostami Nejad M, Shalmani HM, Rostami K, Nazemalhosseini Mojarad E, Aldulaimi D, et al. The effects of gluten-free diet on hypertransaminasemia in patients with celiac disease. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4:700-4. [ Links ]

30. Korpimäki S, Kaukinen K, Collin P, Haapala AM, Holm P, Laurila K, Kurppa K, et al. Gluten-sensitive hypertransaminasemia in celiac disease: an infrequent and often subclinical finding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1689-96. [ Links ]

31. Cordoba J, O'Riordan K, Dupuis J, Borensztajin J, Blei AT: Diurnal variation of serum alanine transaminase activity in chronic liver disease. In: Hepatology. Volume 28. United states, 1998;1724-25. [ Links ]

32. Fraser CG. Biological variation in clinical chemistry. An update: collated data, 1988-1991. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1992;116:916-23. [ Links ]

33. Salvaggio A, Periti M, Miano L, Tavanelli M, Marzorati D. Body mass index and liver enzyme activity in serum. Clin Chem. 1991;37:720-723. [ Links ]

34. Ono T, Kitaguchi K, Takehara M, Shiiba M, Hayami K. Serum-constituents analyses: effect of duration and temperature of storage of clotted blood. Clin Chem. 1981;27:35-8. [ Links ]

35. Volta U, Granito A, De Franceschi L, Petrolini N, Bianchi FB. Anti tissue transglutaminase antibodies as predictors of silent coeliac disease in patients with hypertransaminasaemia of unknown origin. Dig Liver Dis. 2001;33:420-5. [ Links ]

36. Korponay-Szabo IR, Halttunen T, Szalai Z, Laurila K, Kiraly R, Kovacs JB, Fesus L, et al. In vivo targeting of intestinal and extraintestinal transglutaminase 2 by coeliac autoantibodies. Gut. 2004;53:641-8. [ Links ]

37. Caglar E, Ugurlu S, Ozenoglu A, Can G, Kadioglu P, Dobrucali A. Autoantibody frequency in celiac disease. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2009;64:1195-1200. [ Links ]

texto em

texto em