Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Revista colombiana de Gastroenterología

versão impressa ISSN 0120-9957

Rev Col Gastroenterol vol.33 no.3 Bogotá jul./set. 2018

https://doi.org/10.22516/25007440.189

Review articles

Treatment of chronic hepatitis C in elderly patients with chronic kidney disease: a structured review

1Química farmacéutica. Magíster en Investigación y Uso Racional del Medicamento. Estudiante de Doctorado en Ciencias Farmacéuticas y Alimentarias, Universidad de Antioquia. Medellín, Colombia

2Químico farmacéutico. Doctor en Farmacología, Universidad de Antioquia. Medellín, Colombia

Hepatitis C (HC) is a public health problem worldwide and has especially high prevalence in patients over 50 years of age. This population is more prone to suffer from chronic kidney disease (CKD) due to HC infections as well as to age and multiple comorbidities. Those with CKD stages 4 or 5 constitute a population of greater pharmacotherapeutic complexity due to pharmacological variability and limited information on the safety and efficacy of the new antivirals for this group of patients.

Objective:

This article systematizes information about medications and proper dosages for treating chronic HC and is based on studies and reports that include elderly patients with CKD.

Materials and method:

This is a structured review of studies carried out in humans with access to full text published between 01/08/2012 and 01/08/2017 in English or Spanish found in PubMed/Medline using the terms: “Hepatitis C”, “Aged”, and “Renal Insufficiency”.

Results:

Eighty-three articles were identified, fourteen of which were selected. In addition, four manuscripts referenced in those publications were included. A table with antiviral dosing information for treatment of HC in elderly patients with CKD was structured.

Discussion:

We present information on adjustment of dosages of antiviral drugs used for chronic HC in elderly patients and CKD. This could favor prescription and monitoring thereby contributing to the effectiveness and safety of these drugs in this population.

Keywords: Hepatitis C; elderly; kidney diseases; antivirals

La hepatitis C (HC) es un problema de salud pública a nivel mundial, con alta prevalencia en pacientes mayores de 50 años. Esta población es más propensa a sufrir enfermedad renal crónica (ERC), tanto por la infección por el virus de la HC como por su edad y múltiples comorbilidades. Los pacientes con ERC en estadios 4 o 5 pueden ser una población de mayor complejidad farmacoterapéutica, por su variabilidad farmacológica y por la limitada información de seguridad y eficacia de los nuevos antivirales en ese grupo de pacientes.

Objetivo:

sistematizar información de dosificación de medicamentos para la HC crónica, a partir de estudios o reportes que incluyeran pacientes de edad avanzada con ERC.

Materiales y métodos:

revisión estructurada en PubMed/Medline con los términos: “Hepatitis C”, “Aged” y “Renal Insufficiency”; artículos publicados entre 1 de agosto de 2012 y 1 de agosto de 2017, en inglés o español, estudios realizados en humanos, con acceso a texto completo.

Resultados:

se identificaron 83 artículos, de los cuales se seleccionaron 14; además, se incluyeron 4 manuscritos referenciados en las publicaciones revisadas. Se estructuró un cuadro con información de dosificación de antivirales para el tratamiento de la HC en pacientes de edad avanzada con ERC.

Discusión:

Se presenta información sobre el ajuste de dosis de los medicamentos antivirales utilizados para la HC crónica, en pacientes de edad avanzada y ERC, que podría favorecer los procesos de prescripción y seguimiento para contribuir con la efectividad y seguridad de dichos fármacos en esta población.

Palabras clave: Hepatitis C; anciano; enfermedades renales; antivirales

Introduction

Hepatitis C (HC) is an infectious disease caused by the hepatitis C virus (HCV). It is considered a public health problem by the World Health Organization (WHO) because it affects 2% to 3% of the world’s population and is associated with high morbidity and mortality rates. Seventy to ninety percent of infected patients progress to chronic liver diseases such as cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and these diseases are sometimes associated with liver transplantation.1,2 HC affects vulnerable and largely unattended populations such as users of injected drugs and people with inadequate healthcare.

Chronic HC is also associated with extrahepatic manifestations including dermatological, rheumatologic, hematological and renal disorders. 3 The latter may manifest with proteinuria, a decreased glomerular filtration rate (GFR), or even chronic kidney disease (CKD). 3,4,5,6,7,8 The development of CKD due to HCV may be related to the development of glomerulonephritis mediated by the accumulation of cryoglobulins, immune complexes of antibodies against HCV, or by deposition of amyloid. (3,5,9,10

Patients on hemodialysis (HD) are at greater risk of acquiring HCV infections due to repeated exposure to bloodborne pathogens, the need for transfusions, the duration of dialysis, the need for intravenous access and the manipulation of the catheter. 11,12 The result is high prevalence of HCV infection in patients with terminal CKD.12-17 This prevalence is 53% in Colombia. 18

Worldwide, the prevalence of HC is higher in patients over 50 years of age, 19 and, the highest proportion of cases reported in Colombia is found among patients with 65 years old and over. 20 This population is more prone to hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease and obesity which constitute additional risk factors for the development of CKD. 5,21,22 Similarly, typical physiological alterations of age, especially of those organs responsible for metabolism and drug excretion, 23 provoke pharmacological variability which makes this population even more vulnerable to adverse drug events (ADE). 24 Consequently, elderly patients with CKD and chronic HC constitute a population with great pharmacotherapeutic complexity. Furthermore, treatment options for HC in patients with stage 4 or 5 CKD are limited due to poor tolerance and low effectiveness of conventional therapies with interferon (IFN) and ribavirin (RBV). 13,17,25. In addition, there is limited information on the safety and efficacy of current direct-acting antiviral (ADA) regimens given that they have not been adequately evaluated in patients with CKD during clinical trials. 12,26

For these reasons, information on the dosage, effectiveness and safety of antivirals for treating HC in elderly patients with CKD is needed in order to achieve the best possible health outcomes and avoid ADE. Consequently, the objective of this review was to systematize the medication dosage information for chronic HC from studies or reports that included elderly patients with CKD.

Materials and methods

We searched PubMed/Medline for the following terms: “Hepatitis C” [Mesh] AND “Aged” [Mesh] AND “Renal Insufficiency” [Mesh] filtered for studies conducted in humans published between August 1, 2012 and August 1, 2017 in English or Spanish with access to full text. Studies and report whose samples included elderly patients with CKD and HC were included. Articles were excluded if they did not mention pharmacological management of HC in patients with CKD, articles with incomplete dosage information and articles related to drugs withdrawn by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the European Medicines Agency (EMA) or the National Institute of Drug and Food Surveillance of Colombia (INVIMA - Instituto Nacional de Vigilancia de Medicamentos y Alimentos). The search was complemented with publications considered relevant that were referenced in the articles found.

The titles and abstracts of all the articles identified were reviewed by both authors, and decisions to include or exclude articles were made by consensus.

The following information was structured in a database: medication evaluated, HCV genotype, GFR of the patient (s) studied, stage of CKD, dosage used, information on elimination of dialysis, efficacy/effectiveness, ADE, type of study and reference. Efficacy/effectiveness was reported as sustained viral response and defined as undetectable viral load at 12 or 24 weeks after the end of treatment (sustained virological response, SVR12 or SVR24).

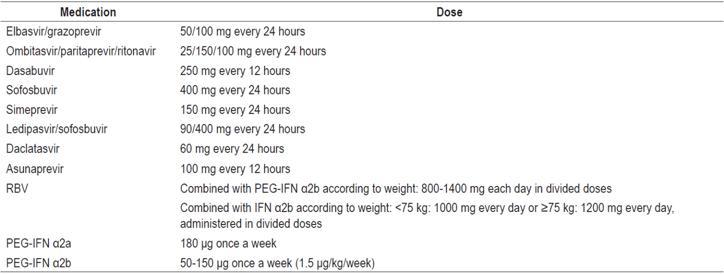

The results obtained were compared with dosages for patients with normal renal functioning (Table 1) and with dosage adjustment recommendations presented in UpToDate® and Micromedex®, two databases frequently used by physicians and pharmacists for posology.

Table 1 Dosages of drugs for treating chronic HCV in patients with normal renal function

Information extracted from medication package inserts. PEG-IFN: pegylated interferon.

RESULTS

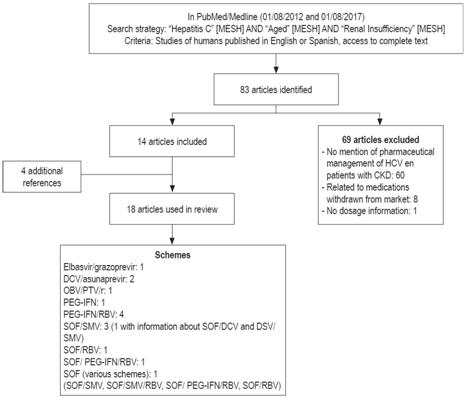

We identified 83 articles of which 14 were included. In addition, four articles referenced in the reviewed publications were considered relevant (Figure 1).

Figure 1 General flowchart of review. DCV: daclatasvir; OBV: ombitasvir; PTV: paritaprevir; r: ritonavir; SMV: simeprevir; SOF: sofosbuvir.

Observational analytical studies accounted for 38.9% of the articles, descriptive observational studies accounted for 33.3% and experimental studies accounted for 27.8%.

Information was identified for seven therapeutic strategies using second generation direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) including elbasvir/grazoprevir, paritaprevir/ombitasvir/ritonavir, dasabuvir, sofosbuvir, simeprevir, daclatasvir and asunaprevir combined with PEG-IFN and/or RBV. The studies and reports reviewed contained information on the use of anti-HCV medications for patients between 18 and 79 years of age.

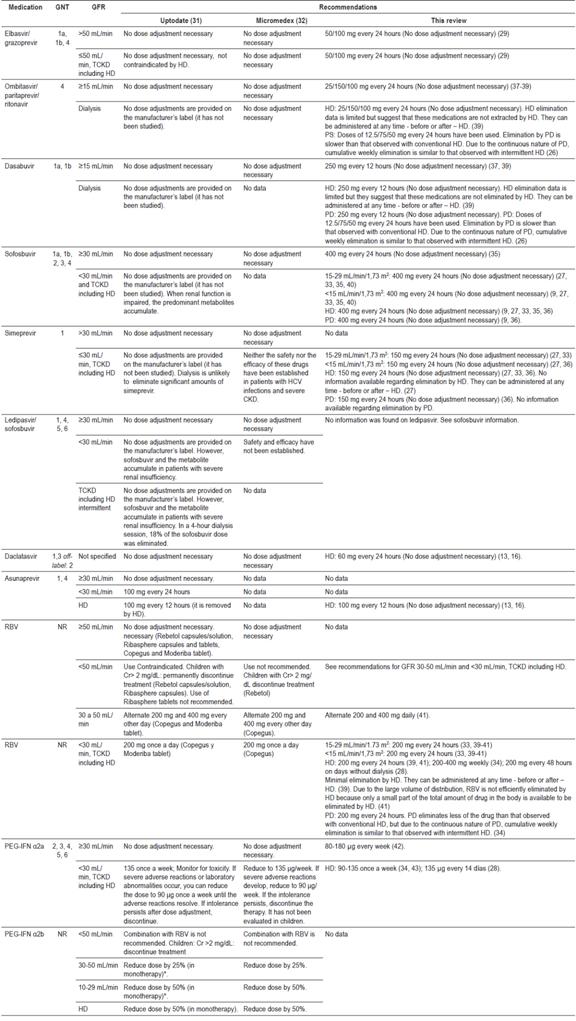

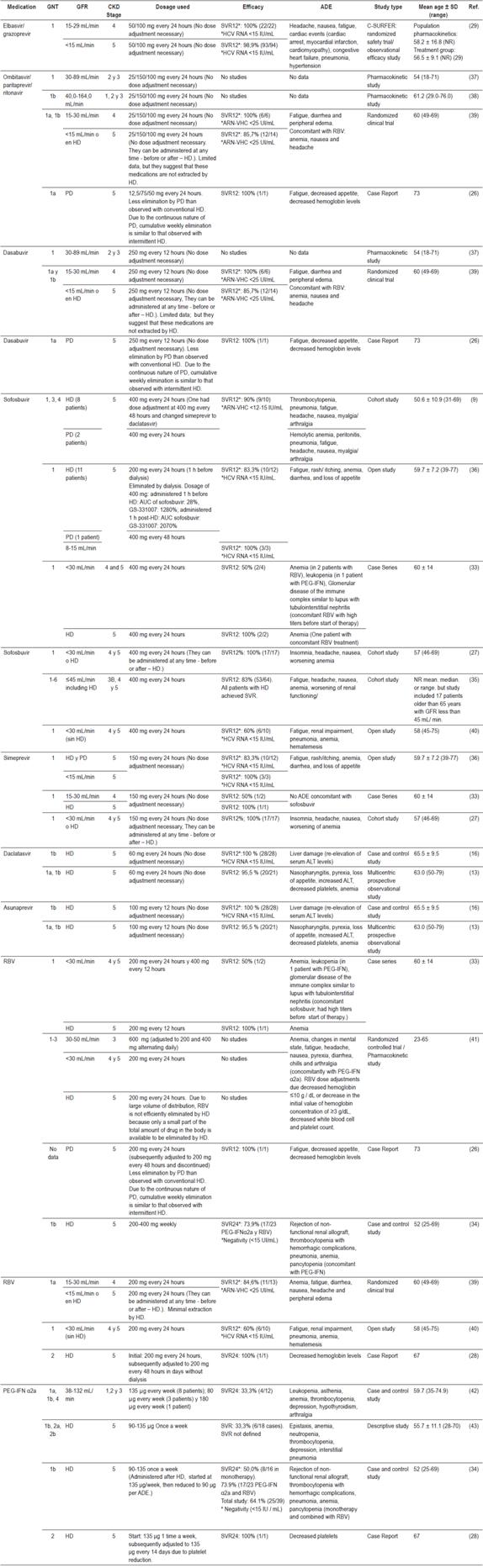

Table 2 shows a summary of the dosage recommendations according to renal function from UpToDate® and Micromedex®) and from the articles and information reviewed for this article. Table 3 presents complete information obtained from our review.

Table 2 Recommendations for adjustment of drug doses for patients with HCV and CKD

* Suspend use if renal functioning decreases during treatment. Cr: creatinine; PD: peritoneal dialysis; TCKD: terminal chronic kidney disease; GNT: genotype; HD: hemodialysis; NR: No report.

Table 3 Results of review of safety and efficacy of drugs for HC in elderly patients with CKD

AUC: area under the curve; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; RNA-HCV: (viral load) ribonucleic acid of hepatitis C virus; PD: peritoneal dialysis; HD: hemodialysis; NR: No report; SVR: sustained virological response.

Discussion

For patients with chronic HC, antiviral treatment is considered essential for preventing complications and improving prognoses, especially when there is evidence of extrahepatic manifestations such as renal alterations that may require dialysis or kidney transplantation. 13,25 In addition, failure to treat patients who have acquired HCV through dialysis and who are waiting for kidney transplantation can allow HC to progress to HCC adding a need for liver transplantation thus adversely affecting allocation of organs and resources for organ transplantation. 27 Failure to treat HCV infections in patients with CKD reduces patient and graft survival (in cases of transplant patients and transplant candidates) and increases mortality. 8,12,13,14,28,29

This review has allowed us to expand the amount of dosing information available for antiviral drugs used to treat HCV in elderly patients with CKD. This information has been structured into a table which may be useful for health professionals involved in prescribing and monitoring these patients. We found information that was not available in UpToDate® and Micromedex®, frequently used databases. This information includes doses of paritaprevir/ombitasvir/ritonavir and dasabuvir for patients with HD and peritoneal dialysis (PD) as well as dosage information for sofosbuvir and simeprevir treatment of patients with GFR less than 30 mL/min who are on either HD or PD. Similarly, the existing information on UpToDate® and Micromedex® has been confirmed for daclatasvir, elbasvir/grazoprevir, PEG-IFN and RBV while information found in UpToDate® on the use of asunaprevir for patients on HD was found to be unsupported because it has not been approved in the United States. This information was not available in Micromedex®.

Among the dosing recommendations that varied the most were those in studies and reports about RBV. Three of the five studies that reported its use in patients with HD showed that doses administered differed from the 200 mg a day recommended in the information of the insert 30 and in the reference databases. 31,32 For example, Hundemer et al. 33 used 200 mg of RBV every 12 hours for one patient who also received sofosbuvir at full doses. That patient developed anemia that required the use of erythropoietin during antiviral treatment although adjustment or suspension of the medications used was not required. Other authors such as Sperl et al. used reduced doses of RBV of 200 to 400 mg weekly in combination with PEF-IFN α2a. 34 In that study, 73.9% (17 of 23 treated) reached SVR at 24 weeks, and only 9 patients presented worsening of anemia. Eight of the nine required erythropoietin, and one patient required transfusion. Similarly, Hidalgo et al. started treatment with 200 mg a day of RBV together with PEG-IFN but had to reduce the dose of RBV to 200 mg every 48 hours due to decreasing hemoglobin in the patient. 28 In addition, it was necessary to increase the dose of Darbepoetin alfa.

There were also differences among sofosbuvir dosages used in HD or PD patients with GFR <15 mL/min/1.73 m2. This can be explained by the lack of information in the drug insert and precautions for renal excretion. Beinhardt et al., Hundemer et al., Nazario et al., and Saxena et al. used sofosbuvir doses of 400 mg daily in patients with a GFR <15 mL/min/1.73 m2 and patients on HD. 9,33,27,35 Bhamidimarri et al. used doses of 400 mg every 48 hours for patients with GFR <15 mL/min/1.73 m2 and 200 mg daily for patients on HD. 36 Only two studies reported the use of sofosbuvir for patients on PD: Beinhardt et al. used full doses while Bhamidimarri et al. adjusted the dose to 400 mg every 48 hours. 9,36

Authors such as Bunchorntavakul C et al. 12 have evaluated the treatment of HCV in patients with GFRs <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 who underwent kidney transplantation or who had CKD related to HCV. Based on the information found, they developed strategies for the management of HCV in patients with CKD and TR that use PEG-IFN, RBV, sofosbuvir, simeprevir, boceprevir and telaprevir (The last two have been withdrawn from the market). Similarly, Sorbera et al. produced a table with dosage recommendations for sofosbuvir, simeprevir, ledipasvir, daclatasvir, ombitasvir/paritaprevir and dasabuvir for use in patients with renal impairment. 11

Unlike the other reviews discussed, this paper presents recommendations about seven therapeutic strategies that use PEG-IFN and RBV and second generation direct acting antivirals: elbasvir/grazoprevir, paritaprevir/ombitasvir/ritonavir, dasabuvir, sofosbuvir, simeprevir, daclatasvir and asunaprevir. We expand the information about the use of sofosbuvir in elderly patients whose GFR is less than 30 mL/min and who are on dialysis. Bunchorntavakul et al. could not include doses for daclatasvir, ombitasvir/paritaprevir, dasabuvir, or elbasvir/grazoprevir since they were not available at the time of their review, and Sorbera et al. neither provided data on the use of asunaprevir at any stage of CKD nor did they provide information on elbasvir/grazoprevir.12,11 In addition, those reviews did not report the ages of the patients included in the studies they reviewed, nor did they present information on ADEs which makes it impossible to know the use, dosage and safety of DAAs in elderly patients with CKD.

Treatment of HC in elderly patients with CKD

Preferably, elderly patients with HC and CKD should be treated with drugs that are not excreted by the kidneys to prevent accumulation of the drugs or their metabolites. On the one hand, elbasvir/grazoprevir, paritaprevir/ombitasvir/ritonavir, dasabuvir, daclatasvir, asunaprevir, ledipasvir and simeprevir are metabolized mainly by the liver while sofosbuvir, the cornerstone of several schemes, has renal excretion (through the inactive metabolite GS-331007). 16,26,44 This may limit concomitant use of other DAAs such as ledipasvir, simeprevir and daclatasvir in patients with TCKD. 26

Currently, the sofosbuvir insert does not contain dosage recommendations for patients whose GFRs are less than 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 or who have TCKD because there is evidence of higher exposures (up to 20 times) of the predominant sofosbuvir metabolite, GS331007. 4,5 However, studies included in this review have shown the successful use of full doses of sofosbuvir (400 mg every 24 hours) in stages 4 and 5 including treatment of patients on HD and PD without major implications for safety. Also, some of the ADEs reported in patients who used sofosbuvir could be primarily associated with concomitant use of PEG-IFN and/or RBV.

Patients with HD should be considered to eliminate a considerable amount sofosbuvir and its predominant metabolite, 45 but authors who reported the use of full doses of this drug in this population do not provide information on the most appropriate time to administer it. For example, Nazario et al. 27 administered sofosbuvir and simeprevir at any time, before or after dialysis, and achieved SVR 12 in 100% of the patients. ADE was not documented during treatment in 76% (13/17) of the patients. Reported ADEs were insomnia (12%), nausea (5%), headache (5%) and anemia (5%). 27

In terms of effectiveness, DAAs achieved SVR12 in 83.3% to 100% of the study populations with high cure rates in patients treated with these schemes. Bhamidimarri et al. 36, achieved an SVR12 in 83.3% of their HD and PD patients (10/12) using adjusted dosages of sofosbuvir while they achieved SVR12 of 100% for patients with GFRs between 8 and15 mL/min (3/3).

Several of the ADEs reported in the studies of different drugs may be associated with high prevalences of comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease in elderly patients with CKD, especially in patients on dialysis.

This structured review offers systematized information on DAA guidelines used in elderly patients with HC and CKD especially in routine clinical practice as well as information on which schemes have proven to be effective and safe in treated patients. This information can strengthen the processes of prescription and pharmacotherapy follow-up thus contributing to the effectiveness and safety of treatment.

Sofosbuvir is one of the most widely used drugs because it inhibits replication of multiple HCV genotypes, has a high genetic barrier to resistance, is well tolerated and has limited potential for drug-drug interactions. 46 Administration of the full dose (400 mg every 24 hours) in elderly patients with stage 4 and 5 CKD, including those on HD or PD can be considered when none of the schemes that are eliminated through the liver are available (elbasvir/grazoprevir, paritaprevir/ombitasvir/ritonavir/dasabuvir, daclatasvir/asunaprevir) or when they are contraindicated. This is the case for patients with decompensated cirrhosis (Child-Pugh B or C) for whom the use of elbasvir /grazoprevir and paritaprevir/ombitasvir/ritonavir/dasabuvir are not indicated.

Given that, as of publication of this review, Colombian and international clinical practice guidelines have not recommended the use of schemes containing sofosbuvir for patients with stages 4 or 5 CKD, including end-stage renal disease, the recommendations of this review should be considered with caution. The decision to treat HC in elderly patients with CKD, especially stages 4 and 5, should be individualized, should consider available medications, should consider risks and expected benefits of treatment, and should consider the patient’s life expectancy and comorbidities. When a decision has been made to use DAAs appropriate dosage adjustments, careful follow-up of renal function, and careful monitoring for the appearance of ADE and SVR are all necessary.

Similarly, the need for prospective safety and effectiveness studies of DAAs for treatment of HCV in elderly patients with CKD is highlighted.

Limitations

This review has several limitations, and the information in it should be interpreted with caution by prescribing physicians. On one hand, we only searched the PubMed/Medline database while the general recommendation for this type of study is to search in two or more databases. However, the review of the references of the articles included could mitigate this limitation. On the other hand, the articles reviewed include information on patients of various age groups, but usually did not classify data according to age. Consequently, it was not possible to extract the dosing and efficacy information exclusively for patients 65 years or older. Despite this, the studies reviewed show the use of DAAs in this age group which could indicate the absence of problems with their use.

In addition, none of the articles reviewed included information for patients aged 80 and older. Consequently, it is not possible to make firm recommendations regarding treatment of this population.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Pharmaceutical Promotion and Prevention Research group of the University of Antioquia in Medellín, Colombia

REFERENCES

1. Hajarizadeh B, Grebely J, Dore GJ. Epidemiology and natural history of HCV infection. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10(9):553-62. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.107. [ Links ]

2. Kohli A, Shaffer A, Sherman A, Kottilil S. Treatment of hepatitis C: a systematic review. JAMA. 2014;312(6):631-40. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.7085. [ Links ]

3. Park H, Adeyemi A, Henry L, Stepanova M, Younossi Z. A meta-analytic assessment of the risk of chronic kidney disease in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Viral Hepat. 2015;22(11):897-905. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12413. [ Links ]

4. Chen YC, Lin HY, Li CY, Lee MS, Su YC. A nationwide cohort study suggests that hepatitis C virus infection is associated with increased risk of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2014;85(5):1200-7. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.455. [ Links ]

5. Li WC, Lee YY, Chen IC, Wang SH, Hsiao CT, Loke SS. Age and gender differences in the relationship between hepatitis C infection and all stages of Chronic kidney disease. J Viral Hepat. 2014;21(10):706-15. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12199. [ Links ]

6. Kurbanova N, Qayyum R. Association of Hepatitis C Virus Infection with Proteinuria and Glomerular Filtration Rate. Clin Transl Sci. 2015;8(5):421-4. doi: 10.1111/cts.12321. [ Links ]

7. American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Patients with Renal Impairment. AASLD [Internet]. 2017 [acceso el 26 de agosto de 2017]. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.hcvguidelines.org/unique-populations/renal-impairment . [ Links ]

8. Blé M, Aguilera V, Rubín A, García-Eliz M, Vinaixa C, Prieto M, et al. Improved renal function in liver transplant recipients treated for hepatitis C virus with a sustained virological response and mild chronic kidney disease. Liver Transpl. 2014;20(1):25-34. doi: 10.1002/lt.23756. [ Links ]

9. Beinhardt S, Al Zoairy R, Ferenci P, Kozbial K, Freissmuth C, Stern R, et al. DAA-based antiviral treatment of patients with chronic hepatitis C in the pre- and postkidney transplantation setting. Transpl Int. 2016;29(9):999-1007. doi: 10.1111/tri.12799. [ Links ]

10. Hsu YC, Lin JT, Ho HJ, Kao YH, Huang YT, Hsiao NW, et al. Antiviral treatment for hepatitis C virus infection is associated with improved renal and cardiovascular outcomes in diabetic patients. Hepatology. 2014;59(4):1293-302. doi: 10.1002/hep.26892. [ Links ]

11. Sorbera MA, Friedman ML, Cope R. New and emerging evidence on the use of second-generation direct acting antivirals for the treatment of hepatitis C virus in renal impairment. J Pharm Pract. 2017;30(3):359-365. doi: 10.1177/0897190016632128. [ Links ]

12. Bunchorntavakul C, Maneerattanaporn M, Chavalitdhamrong D. Management of patients with hepatitis C infection and renal disease. World J Hepatol. 2015;7(2):213-25. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i2.213. [ Links ]

13. Suda G, Kudo M, Nagasaka A, Furuya K, Yamamoto Y, Kobayashi T, et al. Efficacy and safety of daclatasvir and asunaprevir combination therapy in chronic hemodialysis patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Gastroenterol. 2016;51(7):733-40. doi: 10.1007/s00535-016-1162-8. [ Links ]

14. Grimaldi V, Sommese L, Picascia A, Casamassimi A, Cacciatore F, Renda A, et al. Association between human leukocyte antigen class I and II alleles and hepatitis C virus infection in high-risk hemodialysis patients awaiting kidney transplantation. Hum Immunol. 2013;74(12):1629-32. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2013.08.008. [ Links ]

15. Chebrolu P, Colombo RE, Baer S, Gallaher TR, Atwater S, Kheda M, et al. Bacteremia in hemodialysis patients with hepatitis C. Am J Med Sci. 2015;349(3):217-21. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0000000000000391. [ Links ]

16. Toyoda H, Kumada T, Tada T, Takaguchi K, Ishikawa T, Tsuji K, et al. Safety and efficacy of dual direct-acting antiviral therapy (daclatasvir and asunaprevir) for chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection in patients on hemodialysis. J Gastroenterol. 2016;51(7):741-7. doi: 10.1007/s00535-016-1174-4. [ Links ]

17. Lin MV, Sise ME, Pavlakis M, Amundsen BM, Chute D, Rutherford AE, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Direct Acting Antivirals in Kidney Transplant Recipients with Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0158431. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158431. [ Links ]

18. Millet Torres D, Curbelo Rodríguez L, Ávila Riopedre F, Benítez Méndez M, Prieto García F. Overall outcomes in kidney transplant recipients with hepatitis C in a district hospital in Camagüey, Cuba. Nefrologia. 2015;35(5):509-11. doi: 10.1016/j.nefro.2015.06.003. [ Links ]

19. Center for Disease Analysis. Hepatitis C prevalence [Internet]. 2012 [acceso el 19 de febrero de 2017]. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.centerforda.com/HepC/HepMap.html . [ Links ]

20. Instituto Nacional de Salud. Informe del comportamiento en la notificación de los eventos hepatitis B, C y coinfección/suprainfección hepatitis B/delta hasta período epidemiológico VI. Colombia: Instituto Nacional de Salud; 2017. [ Links ]

21. Levey AS, Coresh J. Chronic kidney disease. Lancet. 2012;379(9811):165-80. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60178-5. [ Links ]

22. Chen YC, Chiou WY, Hung SK, Su YC, Hwang SJ. Hepatitis C virus itself is a causal risk factor for chronic kidney disease beyond traditional risk factors: a 6-year nationwide cohort study across Taiwan. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:187. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-14-187. [ Links ]

23. ElDesoky ES. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic crisis in the elderly. Am J Ther. 2007;14(5):488-98. doi: 10.1097/01.mjt.0000183719.84390.4d. [ Links ]

24. Salvi F, Marchetti A, D›Angelo F, Boemi M, Lattanzio F, Cherubini A. Adverse drug events as a cause of hospitalization in older adults. Drug Saf. 2012;35 Suppl 1:29-45. doi: 10.1007/BF03319101. [ Links ]

25. Moorman AC, Tong X, Spradling PR, Rupp LB, Gordon SC, Lu M, et al. Prevalence of Renal Impairment and Associated Conditions Among HCV-Infected Persons in the Chronic Hepatitis Cohort Study (CHeCS). Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61(7):2087-93. doi: 10.1007/s10620-016-4199-x. [ Links ]

26. Stark JE, Cole J. Successful treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection in a patient receiving daily peritoneal dialysis. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2017;74(19):1541-1544. doi: 10.2146/ajhp160729. [ Links ]

27. Nazario HE, Ndungu M, Modi AA. Sofosbuvir and simeprevir in hepatitis C genotype 1-patients with end-stage renal disease on haemodialysis or GFR <30 ml/min. Liver Int. 2016;36(6):798-801. doi: 10.1111/liv.13025. [ Links ]

28. Hidalgo-Collazos P, Marín-Ventura L, Sánchez R, García-López L, Criado-Illana MT. Tratamiento de la infección por virus de la hepatitis C en hemodiálisis. Nefrologia. 2014;34(1):132-3. doi: 10.3265/Nefrologia.pre2013.Sep.12268. [ Links ]

29. Roth D, Nelson DR, Bruchfeld A, Liapakis A, Silva M, Monsour H Jr, et al. Grazoprevir plus elbasvir in treatment-naive and treatment-experienced patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection and stage 4-5 chronic kidney disease (the C-SURFER study): a combination phase 3 study. Lancet. 2015;386(10003):1537-45. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00349-9. [ Links ]

30. Roche Farma S.A. COPEGUS® (ribavirin) Tablets FDA [Internet]. 2011 [acceso el 27 de noviembre de 2017]. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/021511s023lbl.pdf . [ Links ]

31. UpToDate Inc. Drug information [Internet]. [ acceso el 9 de noviembre de 2017]. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search . [ Links ]

32. Truven Health Analytics. Dosing & therapeutic tools database. IBM [internet] [acceso el 9 de noviembre de 2017]. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.micromedexsolutions.com . [ Links ]

33. Hundemer GL, Sise ME, Wisocky J, Ufere N, Friedman LS, Corey KE, et al. Use of sofosbuvir-based direct-acting antiviral therapy for hepatitis C viral infection in patients with severe renal insufficiency. Infect Dis (Lond). 2015;47(12):924-9. doi: 10.3109/23744235.2015.1078908. [ Links ]

34. Sperl J, Frankova S, Senkerikova R, Neroldova M, Hejda V, Volfova M, et al. Relevance of low viral load in haemodialysed patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(18):5496-504. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i18.5496. [ Links ]

35. Saxena V, Koraishy FM, Sise ME, Lim JK, Schmidt M, Chung RT, et al. Safety and efficacy of sofosbuvir-containing regimens in hepatitis C-infected patients with impaired renal function. Liver Int. 2016;36(6):807-16. doi: 10.1111/liv.13102. [ Links ]

36. Bhamidimarri KR, Czul F, Peyton A, Levy C, Hernandez M, Jeffers L, et al. Safety, efficacy and tolerability of half-dose sofosbuvir plus simeprevir in treatment of Hepatitis C in patients with end stage renal disease. J Hepatol. 2015;63(3):763-5. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.06.004. [ Links ]

37. Polepally AR, Badri PS, Eckert D, Mensing S, Menon RM. Effects of mild and moderate renal impairment on ombitasvir, paritaprevir, ritonavir, dasabuvir, and ribavirin pharmacokinetics in patients with chronic HCV infection. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2017;42(2):333-339. doi: 10.1007/s13318-016-0341-6. [ Links ]

38. Gopalakrishnan SM, Polepally AR, Mensing S, Khatri A, Menon RM. Population Pharmacokinetics of Paritaprevir, Ombitasvir, and Ritonavir in Japanese Patients with Hepatitis C Virus Genotype 1b Infection. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2017;56(1):1-10. doi: 10.1007/s40262-016-0423-2. [ Links ]

39. Pockros PJ, Reddy KR, Mantry PS, Cohen E, Bennett M, Sulkowski MS, et al. Efficacy of Direct-Acting Antiviral Combination for Patients With Hepatitis C Virus Genotype 1 Infection and Severe Renal Impairment or End-Stage Renal Disease. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(7):1590-8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.078. [ Links ]

40. Martin P, Gane E, Ortiz-Lasanta G, Liu L, Sajwani K, Kirby B, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Treatment With Daily Sofosbuvir 400 mg + Ribavirin 200 mg for 24 Weeks in Genotype 1 or 3 HCV-Infected Patients With Severe Renal Impairment. Boston: 66th Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases [Internet]; 2015 [acceso el 29 de septiembre de 2017]. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.natap.org/2015/AASLD/AASLD_134.htm [ Links ]

41. Brennan BJ, Wang K, Blotner S, Magnusson MO, Wilkins JJ, Martin P, et al. Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of ribavirin in hepatitis C virus-infected patients with various degrees of renal impairment. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(12):6097-105. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00608-13. [ Links ]

42. Hassan Q, Roche B, Buffet C, Bessede T, Samuel D, Charpentier B, et al. Liver-kidney recipients with chronic viral hepatitis C treated with interferon-alpha. Transpl Int. 2012;25(9):941-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2012.01520.x. [ Links ]

43. Kojima A, Kakizaki S, Hosonuma K, Yamazaki Y, Horiguchi N, Sato K, et al. Interferon treatment for patients with chronic hepatitis C complicated with chronic renal failure receiving hemodialysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28(4):690-9. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12118. [ Links ]

44. Perumpail RB, Wong RJ, Ha LD, Pham EA, Wang U, Luong H, et al. Sofosbuvir and simeprevir combination therapy in the setting of liver transplantation and hemodialysis. Transpl Infect Dis. 2015;17(2):275-8. doi: 10.1111/tid.12348. [ Links ]

45. Gilead Sciences Inc. SOVALDI® (sofosbuvir) tablets, for oral use. FDA [internet]. 2017 [acceso el 3 de noviembre de 2017]. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.gilead.com/~/media/Files/pdfs/medicines/liver-disease/sovaldi/sovaldi_pi.pdf . [ Links ]

46. Yau AH, Yoshida EM. Hepatitis C drugs: the end of the pegylated interferon era and the emergence of all-oral interferon-free antiviral regimens: a concise review. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28(8):445-51. [ Links ]

Received: December 13, 2017; Accepted: January 20, 2018

texto em

texto em