Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista colombiana de Gastroenterología

Print version ISSN 0120-9957

Rev Col Gastroenterol vol.33 no.4 Bogotá Oct./Dec. 2018

https://doi.org/10.22516/25007440.327

Review articles

Serology of hepatitis B virus: multiple scenarios and multiple exams

1Profesor titular de Medicina, Unidad de Gastroenterología, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Hospital Universitario Nacional de Colombia. Gastroenterólogo Clínica Fundadores. Bogotá D. C., Colombia.

2Internista, residente de Gastroenterología, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Hospital Universitario de Colombia. Bogotá D. C., Colombia

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) has an enormous global impact. Despite the availability of a vaccine, two billion people have been acutely infected. Of these, 240 million remain chronically infected. The infection has different forms of presentation including acute infections, chronic infections, hidden infections, and reactivation when there is immunosuppression. Similarly, there are very sensitive markers such as anti-core, but a positive test can have different meanings. This recently described antigen which is related to the core antigen is an emerging marker that could replace viral DNA. In this review we discuss the laboratory tests necessary for diagnosing the various scenarios of the infection.

Keywords: B virus; hidden infection; anti-core; reactivation

El virus de la hepatitis B (VHB) tiene un gran impacto mundial. No obstante la disponibilidad de la vacuna, 2000 millones de personas se han infectado agudamente y, de ellos, 240 millones persisten crónicamente infectados. La infección tiene diferentes formas de presentación tales como infección aguda, infección crónica, infección oculta y reactivación cuando hay inmunosupresión. Así mismo, hay marcadores muy sensibles como el anticore, cuya positividad puede tener diversos significados. El recientemente descrito antígeno relacionado con el antígeno core es un marcador emergente que podría reemplazar al ácido desoxirribonucleico (ADN) viral. En la presente revisión se discuten los exámenes de laboratorio necesarios para el diagnóstico de los diferentes escenarios de la infección.

Palabras clave: Virus B; infección oculta; anticore; reactivación

Introduction

The hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a health problem throughout the world. It is estimated that 2000 million people have been exposed to the virus and that 240 million are chronically infected making it the most frequent chronic viral infection of all. 1,2 Between 15% an 40% of those with chronic infections progress to cirrhosis and its complications, including hepatocellular carcinoma. 3 In 2013, HBV produced 686,000 deaths, 3 an increase of 33% from 1990 to 2013. 3 In 2005, HBV prevalence in Central America was less than 2% and in South America it was 2% to 4%, 3 but in South America there are now 400,000 new cases each year. 3 Despite recommendations for universal vaccination against HBV, this prophylaxis has not been widely implemented in the countries with the highest prevalences due to lack of economic and logistical resources. 3

HBV is a hepatotropic virus with an external envelope and is a member of the Hepadnaviridae family of small deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) viruses (3,200 base pairs). 4,5 Its DNA is partially double-stranded and partially single-stranded, and it has a transcriptional template that is covalently closed circular DNA (cDNA) which is introduced very rapidly into the nucleus of the hepatocyte during acute infection. 6 It belongs to the genus Orthohepadnavirus which infects mammals and the genus Avihepadnaviridae which affects birds 4. It is thought that this virus originated in Africa at least 40,000 years ago. 6 It has 10 genotypes (A-J), A is frequent in North America, Northern Europe and Africa while B and C occur frequently in Asia. 4,7 Some studies have found associations between the genotype, progression of the disease, and response to interferon.4 Genotypes C and F are more frequently associated with hepatocellular carcinoma as well as some subgenotypes of type A. On the other hand, genotype A is associated with risk of progression to chronic infection.4,7 Nevertheless, any acute infection regardless of genotype can progress to a chronic infection. 4

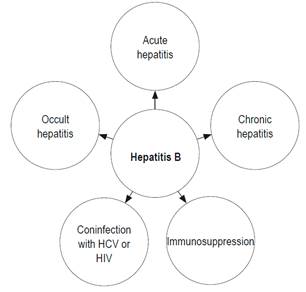

HBV is primarily transmitted through sexual, perinatal, or mucosal routes or through percutaneous parenteral routes resulting from injuries with sharp elements contaminated with infected blood. 8 This last form of transmission includes accidental punctures in hospital environments with contaminated surgical instruments, manicure procedures, pedicures, tattoos, intravenous drug abuse (sharing contaminated syringes) and piercings. 8 Infections from these procedures has decreased as the risks inherent to them have become known, sterilization of medical instruments has been implemented, and reuse of needles has been banned. 9 Sexual transmission has been reduced by education about the use of sexual protection measures. 8,9 Ninety-five percent of cases of vertical transmission occur during vaginal deliveries and 5% occur through intrauterine transmission.8 The clinical spectrum of HBV infection includes acute hepatitis, chronic hepatitis and occult infections. 10 Similarly, HBV can cause cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma and can compromise extrahepatic organs. 11-14

Due to the impact and complexity of HBV infections, this review discuss the various tests used to diagnose the infection in scenarios found in daily practice (Figure 1).

Acute hepatitis b

The diagnosis of acute Hepatitis B is confirmed by a positive blood test for HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) and IgM antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc IgM). 15 HBsAg is the serological marker of HBV infections, 15 but there are cases in which HBsAg disappears rapidly without the appearance of HB surface antibodies. This is the immunological window period in which the only evidence of acute infection with HBV is the IgM antibody. 15 HB surface antibodies appears two weeks after HBsAg and may persist for up to two years. 16 HBsAg is detectable from one week to ten 10 weeks after contact. 2 Detection of anti-HBc IgM coincides with development of general symptoms and increasing aminotransferases. 14

The resolution of acute hepatitis is characterized by disappearance of HBsAg, appearance of anti-HBsAg antibodies, anti-HBc immunoglobulin G (IgG) and normalization of alanine-aminotransferase (ALT) levels.14,15 This profile indicates apparent cure and has been defined as functional healing. 17 Nevertheless, it has been found that despite markers of disappearance of the infection, cDNA persists in the nucleus of the hepatocyte as an episome or minichromosome from which ribonucleic acid (RNA) and this DNA are generated to initiate replication viral. 18. This cDNA remains in the host indefinitely after the first 24 hours of infection. 18 Replication from this reservoir of HBV can restart if immune defense mechanisms are blocked, as occurs with immunosuppression since host immunity controls those infected cells. 19

Recently, the concept of a functional cure has been redefined as the loss of HBsAg with or without the appearance of anti-HBsAg antibody or any HBV DNA detectable in serum, but with the persistence of cDNA.6,13 In contrast, a total cure is functional healing plus elimination of cDNA.20,21 At present, it is impossible to cure HBV infections because the available drugs only suppress viral replication but cannot eliminate cDNA.19,22 The elimination of cDNA is the ideal goal of treatment of chronic HBV infections.6,19

Tests for IgM anti-HBc are positive in 10% to 15% of patients whose chronic HBV infections have reactivated and are indistinguishable from acute infections.15,16,23,24 Nevertheless, other serological characteristics can help differentiate them. In acute infections, the IgM is pentameric and has a molecular weight of 19 S, but in chronic infections, the IGM is monomeric and has a molecular weight of 7 to 8 S. 16 Titers greater than 1:1,000 are seen in 80% of acute infections with a sensitivity of 96.2% and a specificity of 93.1% when determined by enzyme immunoassay. 23 IgM titres less than 1:1,000 are seen in 70% of acutely exacerbated chronic hepatitis B cases.23,24

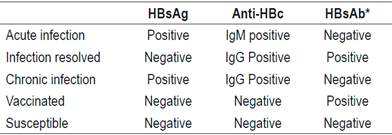

Chronic hepatitis b

An HBV infection is chronic when tests for HBsAg continue to be positive for 6 months after an acute infection is diagnosed.8,9,14 Whether HBV will become chronic depends on the interaction between HBV and the immune system, but the probability increases in cases of with immature immune system and immunosuppressed patients. 25 Ninety-eight percent of HBV cases in newborns become chronic, while twenty to thirty percent of cases among children from one to five years of age become chronic. In contrast, less than 5% of cases in immunocompetent adults become chronic.26,27 A summary of interpretations of findings from HBV serology is shown in Table 1.

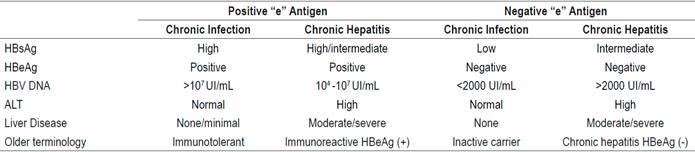

The European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) classifies chronic hepatitis B into 4 types according to positivity for the “e” antigen and the presence or absence of liver disease (Table 2). (28) This new classification replaces the previous nomenclature of expressions including inactive carrier and immunotolerance.

Treatment is indicated in the following situations: 28

Any patient who has chronic hepatitis defined by DNA> 2000 IU/mL and whose ALT is above the upper limit of normal and/or has moderate hepatic necroinflammation or fibrosis) with or without the “e” antigen.

Any patient with compensated or decompensated cirrhosis, regardless of the levels of DNA and ALT.

Any patients with DNA> 20,000 IU/mL and ALT two times the upper limit of normal, regardless of the degree of fibrosis.

Any patient older than 30 years who tests positive for the “e” antigen and has chronic infection and high DNA, levels but persistently normal ALT levels, regardless of the severity of liver histology.

Any patient with a chronic infection whether or not they test positive for the “e” antigen, who has a family history of hepatocellular carcinoma or cirrhosis with extrahepatic manifestations, even though she/he does not meet the typical indications for treatment.

It is recommended that patients with chronic hepatitis B who do not meet the treatment criteria be periodically checked:

Patients who are under 30 years of age who test positive for the “e” antigen should be monitored every 3 to 6 months.

Patients whose tests are negative for the “e” antigen and whose HBV DNA count is less than 2,000 IU/mL should be monitored every 6 to 12 months. If HBV DNA level is over 2,000 IU/mL, they should be monitored every 3 months for the first year and every 6 months thereafter.

Occult hbv infections (obis)

The existence of OBIs was first suspected in the 1970s, but the first publication on the subject was produced in 1999. 29 Initially it was defined as negative test results for HBsAg but findings of HBV DNA in the liver whether or not DNA is detectable in the serum. 30,31 Nevertheless, the difficulty and risks of taking a liver biopsy to identify HBV DNA and lack of standardization for liver DNA, led to its replacement with testing for serum DNA.31,32

In addition, serum determination is adequately standardized and has adaquate sensitivity.31,32 The viral load is usually less than 200 IU/mL, and in more than 90% of cases it is 20 IU/mL. 33 Basic indicators for OBI are a negative test for HBsAg plus findings of HBV DNA in serum. 30 In addition, it can be seropositive or seronegative whether or not anti-HBc IgG or anti HBV surface antibodies are present.30,34,35 The majority of seropositive patients had chronic infections, and HBsAg disappeared spontaneously.34,35 HBsAg disappears annually in 0.5% -2.2% of all cases. 31 Seropositive patients have cytokine profiles that are different from those of seronegative patients. 36 Expression of interferon gamma (IFN-γ) of HBV-specific T cells is lower in seropositive patients. 36 Because of other characteristics seen in animal models of OBI, it is presumed that seropositive and seronegative patients have different forms of infection37,38. The majority of OBI patients (80%) are seropositive. 34

According to the EASL, OBI is typical of the fifth phase of chronic HBV infection and is characterized by the loss of HBsAg while tests for anti-HBc remain positive with or without antisurface antibodies. 30 In these patients, cDNA is responsible for the OBI. 30-35 The detection of DNA during the serological window period of acute infection, when HBsAg is negative, is a “false occult HBV infection”. 30

The consequences of an OBI include the possibility of transmission of infection by transfusions, induction of hepatocellular carcinoma and reactivation of the infection resulting from any type of immunosuppression.31,37 For immunocompetent individuals, OBI is harmless, but when it reactivates, the typical markers of a manifest infection reappear. 38 Initial examinations to investigate OBI are tests for HBsAg and total anti-HBc. By definition, the HBsAg test must be negative. Regardless of the result of the total anti-HBc test, HBV DNA must be investigated. However, to avoid delays in diagnosis, these tests must be done simultaneously. If the OBI criteria are met, the diagnosis is established. 30 If all tests are negative, the patient is susceptible and must be vaccinated against HBV. 39,40,41

OBI is asymptomatic, so it should be suspected and investigated in high-risk patients including:

Those infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and/or chronic hepatitis C.

Those who are immunosuppressed.

Those who have hepatocellular carcinoma.

Those who are on hemodialysis.

Those who have cryptogenic cirrhosis.

Those who have chronic liver disease whose cause has not been identified.

Those who have received a transplant or are scheduled for transplantation.

Those who will receive immunosuppression of any kind. 42

Patients with hepatitis C (HCV) who also have OBI are at risk because elimination of HCV with direct-acting antivirals can lead to reactivation of HCB and produce acute liver failure whose severity can vary even to the point of causing death.43,44,45 In 2016 the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued an alert after registering 24 of these cases between 2013 and 2016. 46 Reactivation was identified in a timely manner in half of these patients, and they were immediately treated with tenofovir/entecavir which resulted in clinical improvement and decreased viral load. The other patients received treatment late, and two died while one underwent liver transplantation. 46 Because of the potential consequences, the FDA recommends that all patients under treatment for chronic HCV infection should be tested for HBV DNA and their liver profiles should be closely monitored. These patients should consult a physician immediately if they develop symptoms of liver damage such as jaundice, discomfort, and fever. If reactivation has begun, they should receive urgent treatment with tenofovir or entecavir. 47

Isolated anti-hbc

The core antigen is the most immunogenic of all the internal components of HBV. 48 Antibodies against the core antigen are produced in all infected patients, regardless of whether or not they resolve the acute infection. 48 As previously mentioned, in acute infections the antibody is IgM whose levels decrease progressively as the infection resolves. They are replaced IgG antibodies which can persist throughout the patient’s life.49,50 The most reliable serological markers of HBV infection are called its epidemiological markers. 49

The finding of total anti-HBc antibodies, without HBsAg and antisurface antibodies, is called isolated anti-HBc. 50,51 Isolated ant-HBc is found mainly among high risk groups including users of intravenous recreational drugs, HCV patients, HIV patients, those on hemodialysis, solid organ transplant recipients and pregnant women. 51

Prevalence of anti-HBc varies from 1% to 32%, 50 and identification of it represents a challenge for the clinician since it can correspond to various situations: 51

A resolved infection (most frequent);

A false positive (frequent in people from regions with low prevalences of HBV) 50,51

An acute infection in which the IgM anti-HBc explains the positivity of the total anti-HBc.

A chronic infection with low levels of replication. This group has the highest risk when they require immunosuppression. 52

The mechanisms involved are explained below.

False Positives

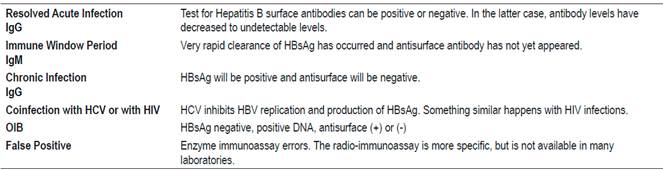

Although immunoassays currently used to identify the total anti-HBc are highly specific, errors that produce incorrect results can occur. 50 Therefore, it is recommended that results be confirmed with a second serum sample.50,61 False positives can be identified with an enzyme immunoassay even though it is less specific than a radioimmunoassay.62,63 This is important because radioimmunoassays are not available in all laboratories so cannot always be used as back up tests. 50,51

HCV and HIV Coinfections (54-60)

Co-infections with HCV or HIV can interfere with HBV replication and the host’s immune response by inducing negative regulation of HBV genes or by modulating the immune response against HBV. 50

Reciprocal inhibition has been demonstrated between HBV and HCV.54,55 The central proteins of HCV inhibit replication of HBV and synthesis of HBsAg.55,57 In HIV infections, the only marker of an HBV infection is likely to be isolated anti-HBc, 50,58 so testing for HBV DNA should be included when investigating HBV in a patient with HIV.

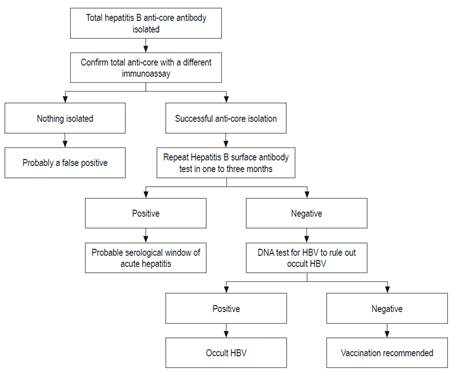

The evaluation of a patient who has tested positive for anti-HBc is shown in Figure 2. 61

Figure 2 Evaluation of patients who are positive for anti-HBc. Modified from: Pondé RA et al. Arch Virol. 2010; 155 (2): 149-58.

A synthesis of the meaning of the isolated anti-HBc is shown in Table 3.

Reactivation of infections

HBV reactivation in individuals who had apparently been cured of acute infection but who then received immunosuppressants was described more than 50 years ago.64,65 Immunocompetence controls HBV, but when it is lost, the virus can reactivate.66,67 Loss of immunocompetence may be spontaneous or induced by immunosuppressants.67,68

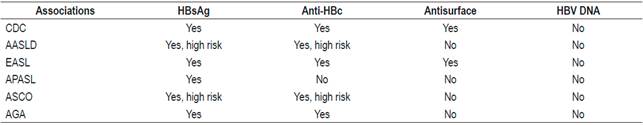

Scientific associations have different recommendations about which HBV tests should be performed before starting immunosuppression (Table 4). 28,68,69,70

Table 4 Recommendations of scientific organizations

AASLD: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; AGA: American Gastroenterological Association; APASL: Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver; ASCO: American Society of Clinical Oncology; CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

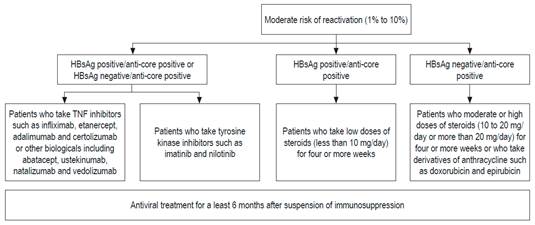

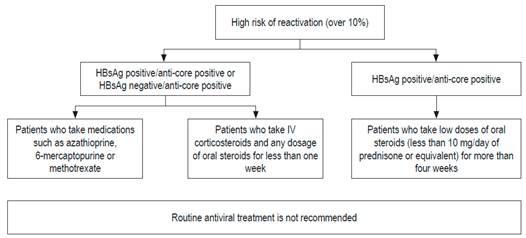

These differences are probably due to the lack of prospective studies and the varying prevalences of HBV in different parts of the world. 69 In the Asian Pacific guide, total anti-HBc is not requested, because that region’s HBV prevalence is very high: around 30%. 71 Based on published evidence, all patients undergoing chemotherapy or immunosuppression should have HBsAg, total anti-HBc and antisurface antibody tests. If they have only test positive for anti-HBc, a test for HBV DNA should be done.72,73,74 These recommendations are also valid for patients who have concomitant diseases that impair immunity.72,73,74 The risk of reactivation depends on the serological profile and the type of chemotherapy. Immunosuppression schemes that most frequently induce reactivation are those that include rituximab. This chimeric monoclonal antibody against the CD20 protein is mainly expressed in the plasma membrane of B cells. 74-77 Recently, the AGA published guidelines on immunosuppression and HBV infections whose recommendations are based on stratification of the risk of reactivation. 68,69 Those recommendations are presented in Figures 3, 4 and 5. 72

Figure 3 Patients with a high risk of reactivation of HBV. Modified from: American Gastroenterological Association. Gastroenterology 2015; 148 (1): 220.

Figure 4 Patients with moderate risk of reactivation of HBV. anti-TNF: inhibitor of tumor necrosis factor. Modified from: American Gastroenterological Association. Gastroenterology 2015; 148 (1): 220.

Figure 5 Patients with low risk of reactivation. Modified from: American Gastroenterological Association. Gastroenterology 2015; 148 (1): 220.

If a patient tests positive for HBsAg, and antiviral prophylaxis is not used, the risk of reactivation is 30% to 80%. These patients should be treated with adefovir or entecavir. 73 The origin of reactivation is the cDNA, but as the amount of antisurface antibodies increases, the risk of reactivation decreases. 68,69 One study found HBV did not reactivate in any of ten patients whose antisurface antibody levels were above 100 IU/mL. 74 Reactivation is identified by changes in DNA and ALT. 68 In patients who are HBsAg positive who test positive for anti-HBc and HBV DNA, reactivation is confirmed if the amount of HBV DNA is raised 1 Log (10 times) or if the test for DNA is positive when it was negative previously. 69,76 The ALT may be three or more times the normal upper limit. When the amount of these enzymes increases, patients prognoses worsen. 76 Clinical manifestations of reactivation range from asymptomatic to acute liver failure and death. 76,77 The recommendation of the AGA is to provide prophylactic treatment rather than simply monitoring DNA. 68

When monitoring indicates reactivation is likely the behavior is called deferred treatment. 68 Reactivation can also occur in patients who have had resolved acute infections with serologic evidence of functional cure (negative HBsAg, positive antisurface with positive or negative anti-HBc) 75,76,77. HBV reactivates in 16% of these cases when they undergo chemotherapy containing rituximab. 75 For patients with resolved infections, the recommendation is to monitor viral DNA every 4 weeks and if it becomes positive, therapy for HBV should be administered. 76 A recent study compared monitoring this type of patient with treating them prophylactically. 78 At 18 months of follow-up, the virus had reactivated in 3/28 patients in the monitoring group but had not reactivated in any (0/33) of those who received prophylactic therapy with tenofovir. 78 Since this difference was not statistically significant, a study with a larger sample size is needed to determine which is the best option or whether there are any differences. In the latter case, the choice will depend on the cost of the drugs versus the cost of measuring DNA every 4 weeks.

For patients who have infection markers, the recommendation is antiviral drugs that target HBV. Adefovir and entecavir are recommended because of their low capacities of inducing HBV resistance. Despite the high risk of reactivation, the availability of clinical practice guidelines on the subject and HBV research among oncologists in the United States is suboptimal. 68,75,79

Other markers of hbv infection

Hepatitis B Core Related Antigen (HBcrAg)

HBcrAg is a new marker of HBV infection. First described in 2002, it is being used for monitoring and establishing prognoses.80,81 Its serum concentration has an excellent correlation with HBV DNA in the blood, but it is superior to HBV DNA for determining viral replication and intrahepatic cDNA. 82 HBV DNA and HBsAg in blood are a reflection of intrahepatic cDNA, but HBcrAg is more sensitive than these classic markers. Seventy-eight percent of patients who have test negative for DNA due to antiviral treatment still test positive HBcrAg. 83 Another study by Lai et al. found that 51% of patients who tested negative for HBV DNA had liver biopsies that tested positive for cDNA. 84

Similarly, other studies have shown that there is no correlation between the disappearance of serum DNA and the disappearance of intrahepatic cDNA. 80 In contrast, HBcrAg is a better reflection of cDNA. 80 Patients whose tests are negative for HBsAg, positive for anti-HBc, negative for DNA and positive for HBcrAg positive while undergoing chemotherapy have a reactivation rate that can reach 40%. 85 Due to the greater sensitivity of HBcrAg as a marker of cDNA, it is considered to be a very promising new tool which could allow better monitoring of the treatment of chronic HBV infections and which could become very useful for monitoring reactivation of HBV in patients with OBI. 80

Acknowledgements

The authors are indebted to Dr. Sandra Rubiano and Dr. Walter Chávez, excellent internists and teachers from Colombia, for their critical reading of the initial manuscript and for their recommendations which significantly improved this study

REFERENCES

1. World Health Organization. Global health sector strategy on viral hepatitis 2016-2021. [internet] 2018 [acceso el 1 de marzo de 2018]. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.who.int/hepatitis/strategy2016-2021/ghss-hep/en/ [ Links ]

2. World Health Organization. Hepatitis B. [internet] 2018 [acceso el 1 de marzo de 2018]. Disponible en: Disponible en: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-b [ Links ]

3. Stanaway JD, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Fitzmaurice C, Vos T, Abubakar I, et al. The global burden of viral hepatitis from 1990 to 2013: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2016:388;1081-8. [ Links ]

4. Peeridogaheh H, Meshkat Z, Habibzadeh S, Arzanlou M, Shahi JM, Rostami S, et al. Current concept on immunopathogesis of hepatitis B virus infection. Vir Res. 2018;245:29-43. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2017.12.007. [ Links ]

5. Sandhu P, Haque M, Humphries-Bickley T, Ravi S, Song J. Hepatitis B virus immunopathology, model systems, and current therapies. Front Immunol. 2017;8: Article 436. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00436. [ Links ]

6. Li X, Zhao J, Yuan Q, Xia N. Detection of HBV Covalently Closed Circular DNA. Viruses. 2017;9(6). pii: E139. doi: 10.3390/v9060139. [ Links ]

7. Valaydos ZS, Locarnini SA. The virological aspects of hepatitis B. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;31:257-64. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2017.04.013. [ Links ]

8. Yang S, Wang D, Zhang Y, Yu C, Ren J, Xu K, et al. Transmission of Hepatitis B and C Virus Infection Through Body Piercing: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(47):e1893. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001893. [ Links ]

9. Yuen MF, Ahn SH, Chen DS, Chen PJ, Dusheiko GM, Hou JL, et al. Chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Disease revisited and management recommendations. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50:286-94. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000478. [ Links ]

10. Fattocich G, Bortolotti F, Donato F. Natural history of chronic hepatitis B: special emphasis on disease progression and prognostic factors. J Hepatol. 2008;48:335-52. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.11.011. [ Links ]

11. Schweitzer A, Horn J, Mikolajczyk RT, Krause G, Ott JJ. Estimations of 2080 worldwide prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: A systematic 2081 review of data published between 1965 and 2013. Lancet 2015;386:1546-55. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61412-X. [ Links ]

12. Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2095-128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [ Links ]

13. Seeger C, Mason W. Molecular biology of hepatitis B virus infection. Virology. 2015;479-480:672-86. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.02.031. [ Links ]

14. Trepo C, Chan H, Lok A. Hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet. 2014;384 (9959):2053-63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60220-8. [ Links ]

15. Villar LM, Medina-Cruz H, Ribeiro-Barbosa J, Souz-Bezerra C, Machado-Portilho M, Scalioni L. Update on hepatitis B and C virus diagnosis. World J Virol. 2015;4(4):323-42. doi: 10.5501/wjv.v4.i4.323. [ Links ]

16. Pondé RAA. Acute hepatitis B virus infection or cute exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B infection: the differential serological diagnosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;35:29-40. doi: 10.1007/s10096-015-2522-7. [ Links ]

17. Durantel D. New treatments to reach functional cure: virological approaches. Best Pract res Clin Gastroenterol 2017;31:329-36. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2017.05.002. [ Links ]

18. Valaydon ZS, Locarnini SA. The virological aspects of hepatitis B. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;31:257-64. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2017.04.013. [ Links ]

19. Hong X, Kim ES, Guo H. Epigenetic regulation of hepatitis B virus covalently closed circular DNA: implications for epigenetic therapy against chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 2017;66(6):2066-77. doi: 10.1002/hep.29479. [ Links ]

20. Durantel D, Zoulim F. New antiviral targets for innovative treatment concepts for hepatitis B virus and hepatitis delta virus. J Hepatol. 2016;64:S117-31. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.02.016. [ Links ]

21. Zeisel MB, Lucifora J, Mason WS, Sureau C, Beck J, Levrero M, et al. Towards an HBV cure: state of the art and unresolved questions-report of the ANRS workshop on HBV cure. Gut. 2015;64(8):1314-26. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308943. [ Links ]

22. Schreiner S, Nassal M. A role for the host DNA damage response in hepatitis B virus cccDNA formation and beyond? Viruses. 2017;9(5):125. https://doi.org/10.3390/v9050125 [ Links ]

23. Han Y, Tang Q, Zhu W, Zhang Y, You L. Clinical, biochemical, immunological and virological profiles of and differential diagnosis between, patients with acute hepatitis B and chronic hepatitis B with acute flare. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1728-33. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05600.x. [ Links ]

24. Kumar M, Jain S, Sharma BC, Sarin SK. Differentiating acute hepatitis B from the first episode of symptomatic exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51(3):594-9. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-3175-2. [ Links ]

25. Lin CJ, Kao JH. Natural history of acute and chronic hepatitis B: the role of HBV genotypes and mutants. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;31:249-55. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2017.04.010. [ Links ]

26. Beasley RP. Rocks along the road to the control of HBV and HCC. Ann Epidemiol 2009; 19:231-4. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.01.017. [ Links ]

27. Sherlock S. The natural history of hepatitis B. Postgrad Med J. 1987;63:7-11. [ Links ]

28. European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL 2017 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol 2017;67:370-98. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.03.021. [ Links ]

29. Cacciola I, Pollicino T, Squadrito G, Cerenzia G, Orlando ME, Raimondo G. Occult hepatitis B virus infection in patients with chronic hepatitis C liver disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:22-6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907013410104. [ Links ]

30. Raimondo G, Allain JP, Brunetto MR, Buendía MA, Chen DS, Colombo M, et al. Statements from the Taormina expert meeting on occult hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2008;49:652-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.07.014. [ Links ]

31. Kwak MS, Kim YJ. Occult hepatitis B virus infection. World J Hepatol. 2014;6(12):860-9. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v6.i12.860. [ Links ]

32. Kang SY, Kim MH, Lee WI. The prevalence of “ati-HBc alone” and HBV DNA detection among anti -HBc alone en Korea. J Med Virol. 2010;82:16508-14. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21862. [ Links ]

33. Yuen MF, Lee CK, Wong DK, Fung J, Hung I, Hau A, et al. Prevalence of occult hepatitis B infection in a highly endemic area for chronic hepatitis B: a study of a large blood donor population. Gut 2010; 59:1389-93. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.209148. [ Links ]

34. Makvandi M. Update on occult hepatitis B virus infection World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(39):8720-34. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i39.8720. [ Links ]

35. Sagnelli C, Macera M, Pisaturo M, Zampino R, Coppola M, Sagnelli E. Occult HBV infection in the oncohematological setting. Infection. 2016; 44(5):575-82. doi: 10.1007/s15010-016-0891-1. [ Links ]

36. Zerbini A, Pilli M, Boni C, Fisicaro P, Penna A, Di VP, et al. The characteristics of the cell-mediated immune response identify different profiles of occult hepatitis B virus infection. Gastroenterology 2008; 134:1470-81. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.017. [ Links ]

37. Mulrooney-Cousins PM, Michalack TI. Persistent occult hepatitis B virus infection:experimental findings and clinical implications. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:5682-6. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i43.5682. [ Links ]

38. Raimondo G, Caccamo G, Filomia R, Pollicino T. Occult HBV infection. Sem Immunopathol. 2013;35:39-52. doi: 10.1007/s00281-012-0327-7. [ Links ]

39. Mohsen W, Levy MT. Hepatitis A to E: what’s new? Intern Med J. 2017;47:380-9. doi: 10.1111/imj.13386. [ Links ]

40. Gisbert JP, Chaparro M, Esteve M. Review article: prevention and management of hepatitis B and C infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011; 33:619-33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04570.x. [ Links ]

41. Melmed GY. Vaccination strategies for patients with inflammatory bowel disease on immunomodulators and biologics. Inflam Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1410-6. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20943. [ Links ]

42. Squadrito G, Spinella R, Raimondo G. The clinical significance of occult HBV infection. Ann Gastroenterol. 2014;27(1):15-9. [ Links ]

43. Fabbri G, Mastrorosa I, Vergori A, Mazzotta V, Pinnetti C, Grisetti S, et al. Reactivation of occult HBV infection in an HIV /HCV co-infected patient successfully treated with sofosbuvir/ledipasvir: a case report and review of the literature. BMC infect Dis. 2017;17:182. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2287-y. [ Links ]

44. Chen G, Wang C, Chen J, Ji D, Wang Y, Wu V, et al. Hepatitis B reactivation in hepatitis B and C coinfected patients treated with antiviral agents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2017;66(1):13-26. doi: 10.1002/hep.29109. [ Links ]

45. Perrillo RP. Hepatitis B virus reactivation during direct-acting antiviral treatment of chronic hepatitis C: A hidden danger of an otherwise major success story. Hepatology. 2017;66(1):4-6. doi: 10.1002/hep.29185. [ Links ]

46. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA warns about the risk of hepatitis B reactivating in some patients treated with direct-acting antivirals for hepatitis C. FDA [internet] 2016 [acceso el 27 de diciembre de 2017]. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/UCM523499.pdf . [ Links ]

47. Zhou K, Terrault N. Management of hepatitis B in special populations. Best Pract Res Clinl Gastroenterol. 2017;31:311-20. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2017.06.002. [ Links ]

48. Milich DR, McLachlan A. The nucleocapsid of hepatitis B virus is both a T-cell-independent and a T-cell-dependent antigen. Science. 1986;234:1398-1401. doi: 10.1126/science.3491425. [ Links ]

49. Busch MP. Should HBV DNA NAT replace HBsAg and/or anti-HBc screening of blood donors? Tranfus Clin Biol. 2004;11(1):26-32. doi: 10.1016/j.tracli.2003.12.003. [ Links ]

50. Wang Q, Klenerman P, Semma N. Significance of anti-HBc alone serological status in clinical practice. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2(2):123-34. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(16)30076-0. [ Links ]

51. Wu T, Kwok RM, Tran TT. Isloated anti HBc: the relevance of hepatits B core antibody: a review of new issues. Am J Gastroenterol 2017;112:1780-8. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.397. [ Links ]

52. Marusawa H, Uemoto S, Hijikata M, Ueda Y, Tanaka K, Shimotohno K, et al. Latent hepatitis B virus infection in healthy individuals with antibodies to hepatitis B core antigen. Hepatology. 2000;31(2):488-95. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310232. [ Links ]

53. Berger A, Doerr HW, Rabenau HF, Weber B. High frequency of HCV infection in individuals with isolated antibody to hepatitis B core antigen. Intervirology 2000;43:71-6. doi: 10.1159/000025026. [ Links ]

54. Marusawa H, Osaki Y, Kimura T, Ito K, Yamashita Y, Eguchi T, et al. High prevalence of anti-hepatitis B virus serological markers in patients with hepatitis C virus related chronic liver disease in Japan. Gut. 1999;45(2):284-8. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2.284. [ Links ]

55. Jilg W, Sieger E, Zachoval R, Schätzl H. Individuals with antibodies against hepatitis B core antigen as the only serological marker for hepatitis B infection: high percentage of carriers of hepatitis B and C virus. J Hepatol. 1995;23(1):14-20. [ Links ]

56. Wedemeyer H, Cornberg M, Tietmeyer B. Isolated anti-HBV core phenotype in anti-HCV-positive patients is associated with hepatitis C virus replication. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004;10:70-2. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.00771.x. [ Links ]

57. Chu CM, Yeh CT, Liaw YF. Low-level viremia and intracellular expression of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) in HBsAg carriers with concurrent hepatitis C virus infection. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2084-6. [ Links ]

58. Wagner AA, Denis F, Weinbreck P, Loustaud V, Autofage F, Rogez S, et al. Serological pattern ‘anti-hepatitis B core alone’ in HIV or hepatitis C virus-infected, patients is not fully explained by hepatitis B surface antigen mutants. AIDS. 2004;18(3):569-71. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200402200-00028. [ Links ]

59. Piroth L, Binquet C, Vergne M, Minello A, Livry C, Bour JB, et al. The evolution of hepatitis B virus serological patterns and the clinical relevance of isolated antibodies to hepatitis B core antigen in HIV infected patients. J Hepatol. 2002;36(5):681-6. [ Links ]

60. Loustaud-Ratti V, Wagner A, Carrier P, Marczuk V, Chemin I, Lunel F, et al. Distribution of total DNA and cccDNA in serum and PBMCs may reflect the HBV immune status in HBsAg+ and HBsAg- patients coinfected or not with HIV or HCV. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2013;37(4):373-83. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2012.11.002. [ Links ]

61. Pondé RA, Cardoso DD, Ferro MO. The underlying mechanisms for the ‘anti-HBc alone’ serological profile. Arch Virol. 2010;155(2):149-58. doi: 10.1007/s00705-009-0559-6. [ Links ]

62. Parkinson AJ, McMahon BJ, Hall D, Ritter D, Fizgerald MA. Comparison of enzyme immunoassay with radioimmunoassay for the detection of antibody to hepatitis core antigen as the only marker of hepatitis B infection in a population with a high prevalence of Hepatitis B. J Med Virol. 1990;30:253-7. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890300405. [ Links ]

63. Silva AE, McMahon BJ, Parkinson AJ, Sjögren MH, Hoofnagle JH, Di Bisceglie AM. Hepatitis B virus DNA in persons with isolated antibody to hepatitis B core antigen who subsequently received hepatitis B vaccine. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:895-7. doi: 10.1086/513918. [ Links ]

64. Galbraith RM, Eddleston AL, Williams R, Zuckerman AJ. Fulminant hepatic failure in leukaemia and choriocarcinoma related to withdrawal of cytotoxic drug therapy. Lancet. 1975;2:528-30. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(75)90897-1. [ Links ]

65. Nagingthon J. Reactivation of hepatitis B after transplantation operations. Lancet. 1977;1:558-60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(77)91995-X. [ Links ]

66. Martinot-Peignoux M, Asselah T, Marcellin P. HBsAg Quantification to Optimize Treatment Monitoring in Chronic Hepatitis B Patients. Liver Int. 2015;35(Suppl 1):82-90. doi: 10.1111/liv.12735. [ Links ]

67. Di Bisceglie AM, Lok AM, Martin P, Terrault N, Perillo RP, Hoofnagle JH. Recent US Food and Drug Administration warnings on hepatitis B reactivation with immune-suppresing and anticancer drugs: just the tip of the iceberg?. Hepatology. 2015;61(2):703-11. doi: 10.1002/hep.27609. [ Links ]

68. Perrillo RP, Gish R, Falck-Ytter YT. American Gastroenterological Association Institute technical review on prevention and treatment of hepatitis B virus reactivation during immunosuppressive drug therapy. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:221-44. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.10.038. [ Links ]

69. Reddy KR, Beavers KL, Hammond SP, Lim JK, Falck-Ytter Y. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on the prevention and treatment of hepatitis B virus reactivation during immunosuppressive drug therapy. Gastroenterology 2015; 148:215-9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.10.039. [ Links ]

70. Bessone F, Dirchwolf M. Management of hepatitis B reactivation in immunosupressed patients: an update on current recommendations. World J Hepatol. 2016;8(8)385-94. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v8.i8.385. [ Links ]

71. Lau GKK. How do we handle the ant-HBc positive patient (in highly endemic settings): The Anti-HBc positive patient. Clinical Liver Disease 2015;5:29-31. doi: 10.1002/cld.399. [ Links ]

72. American Gastroenterological Association. AGA Institute guidelines on Hepatitis B reactivation (HBVr): Clinical Decision Support Tool. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(1):220. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.11.040. [ Links ]

73. Paul S, Dickstein A, Saxena A, Terrin N, Viveiros K, Balk EM, et al. Role of Surface antibody in hepatitis B reactivation in patients with resolved infection and hematologic malignancy: a meta-analysis. Hepatology 2017;66 (2):379-88. doi: 10.1002/hep.29082. [ Links ]

74. Pei SN, Ma MC, Wang MC, Kuo CY, Rau KM, Su CY, et al. Analysis of hepatitis B surface antibody titers in B cell lymphoma patients after rituximab therapy. Ann Hematol. 2012;91(7):1007-12. doi: 10.1007/s00277-012-1405-6. [ Links ]

75. Mozessohn L, Chan KK, Feld JJ, Hicks LK. Hepatitis B reactivation in HBsAg-negative/HBcAb-positive patients receiving rituximab for lymphoma: a meta-analysis. J Viral Hepat. 2015;22:842-9. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12402. [ Links ]

76. Loomba R, Liang TJ. Hepatitis B Reactivation Associated With Immune Suppressive and Biological Modifier Therapies: Current Concepts, Management Strategies, and Future Directions. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(6):1297-309. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.02.009. [ Links ]

77. Paul S, Saxena A, Terrin N, Viveiros K, Balk EM, Wong JB. Hepatitis B virus reactivation and prophylaxis during solid tumor chemotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2016; 164:30-40. doi: 10.7326/M15-1121. [ Links ]

78. Buti M, Manzano ML, Morillas RM, García-Retortillo M, Martín L, Prieto M, et al. Randomized prospective study evaluating tenofovir disoproxil fumarate prophylaxis against hepatitis B virus reactivation in anti HBc-positive patients with rituximab-based regimens to treat hematologic malignancies: the PREBLIN study. Plos One. 2017;12(9):e0184550. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184550. [ Links ]

79. Kwak YE, Stein SM, Lim JK. Practice Patterns in Hepatitis B Virus Screening Before Cancer Chemotherapy in a Major US Hospital Network. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63(1):61-71. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4850-1. [ Links ]

80. Mak LY, Wong DKH, Cheung KS, Seto WK, Lai CL, Yiuen MF. Hepatitis B core-related antigen (HBcrAg): an emerging marker for chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:43-54. doi: 10.1111/apt.14376. [ Links ]

81. Ji M, Hu K. Recent advances in the study of hepatitis B virus covalently closed circular DNA. Virol Sin. 2017;32(6):454-464. doi: 10.1007/s12250-017-4009-4. [ Links ]

82. Kimura T, Rojuhara A, Sakamoto Y. Sensitive enzyme immunoassay for hepatitis B virus core-related antigens and their correlation to virus load. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:439-45. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.2.439-445.2002. [ Links ]

83. Wang DK, Seto WK, Cheung KS. Hepatitis B virus core-related antigen as a surrogate marker for covalently closed circular DNA. Liver Intern. 2017;37:995-1001. doi: 10.1111/liv.13346. [ Links ]

84. Lai CL, Wong DP. Reduction of covalently closed circular DNA with long-term nucleos(t)ide analogue treatment in chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2017;66:275-1. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.08.022. [ Links ]

85. Yeo W, Chan PK, Zhong S, Ho WM, Steinberg JL, Tam JS, et al. Frequency of hepatitis B virus reactivation in cancer patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy: a prospective study of 626 patients with identification of risk factors. J Med Virol. 2000;62(3):299-307. [ Links ]

Received: February 05, 2018; Accepted: March 12, 2018

text in

text in