Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista colombiana de Gastroenterología

versión impresa ISSN 0120-9957

Rev Col Gastroenterol vol.35 no.1 Bogotá ene./mar. 2020

https://doi.org/10.22516/25007440.331

Case report

Chronic diarrhea as a manifestation of a neuroendocrine tumor

1Médico internista endocrinólogo; Hospital Universitario Mayor Méderi. Docente del Departamento de Nutrición Humana; Facultad de Medicina de la Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Docente en la Escuela de Medicina y Ciencias de la Salud; Universidad del Rosario. Bogotá, Colombia

2Médica internista endocrinóloga. Docente del Departamento de Ciencias Fisiológicas de la Facultad de Medicina; Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Endocrinóloga, Instituto Nacional de Cancerología. Bogotá, Colombia

3Médica epidemióloga; Universidad Autónoma de Bucaramanga. Hospital Universitario Mayor Méderi. Bogotá, Colombia

4Médica epidemióloga; Universidad Autónoma de Bucaramanga. Hospital Universitario Mayor Méderi. Bogotá, Colombia

5Médico residente del primer año de Neurología; Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Bogotá, Colombia

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are a heterogeneous group of rare neoplasms that originate in endocrine cells with the ability to secrete amines and hormonal polypeptides. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs) can be functional or non-functional. Functional PNETs secrete common hormones such as gastrin, insulin and glucagon and much less frequent hormones such as vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP). Their characteristics depend on the peptide secreted. Vipomas are characterized by chronic diarrhea of secretory characteristics that usually lead to hydroelectrolytic disorders and can lead to serious complications associated with renal failure. This article describes the case of a 37-year-old man who had suffered chronic diarrhea with frequent hospitalization for hydroelectrolytic disorders for six months due to severe hypokalemia and acute renal damage due to dehydration. After multiple studies, a diagnosis of secretory diarrhea due to a VIP secretory functional NET was considered. Empirical therapy with Octreotide was begun to control diarrhea and correct the hydroelectrolytic disorder. More studies of PNETS are being published. They have been treated surgically intervention with favorable clinical results and complete remission of symptoms.

Keywords: Chronic diarrhea; secretory diarrhea; neuroendocrine tumor; vipoma

Las neoplasias neuroendocrinas (Neuroendocrine Neoplasms, NEN) constituyen un grupo heterogéneo de neoplasias poco frecuentes, que se originan en las células endocrinas, con la capacidad de secretar aminas y polipéptidos hormonales. Las NEN de localización pancreática (pNEN) pueden ser funcionales o no funcionales. Las pNEN funcionales secretan hormonas como la gastrina, la insulina y el glucagón y otras menos frecuentes como el péptido intestinal vasoactivo (PIV), por lo que sus características sindromáticas dependen del péptido secretado. Los vipomas se manifiestan con diarrea crónica de características secretoras, que usualmente conducen a trastornos hidroelectrolíticos e incluso a complicaciones serias asociadas como la falla renal. A continuación, se describe el caso de un hombre de 37 años con diarrea crónica de 6 meses de evolución y frecuentes hospitalizaciones por trastornos hidroelectrolíticos, generados por hipocalemia severa y lesión renal aguda por deshidratación. Después de múltiples estudios, se considera el diagnóstico de una diarrea secretora por NEN funcional, secretora de PIV. Por tanto, se inicia una terapia empírica con octreotida y se logra controlar la diarrea, así como corregir el trastorno hidroelectrolítico. Además, se amplían los estudios, para documentar las pNEN tratadas mediante intervención quirúrgica, con respuesta clínica favorable y remisión completa de la sintomatología.

Palabras clave: Diarrea crónica; diarrea secretora; tumor neuroendocrino; vipoma

Introduction

Diarrhea is defined as a significant reduction in stool consistency or an increase in stool volume to more than 200 g/d. Generally, it is associated with abdominal discomfort or an urge to defecate. Chronic diarrhea is considered last more than 3 weeks although some authors say more than four weeks. 1-3

Chronic diarrhea is classified into three main groups:

Watery diarrhea is in turn subdivided into osmotic, secretory, and functional diarrhea. In osmotic, diarrhea, intraluminal water is retained by unabsorbed substances. In secretory diarrhea, absorption of water is reduced while functional diarrhea is generated by hypermotility.

Fatty diarrhea (steatorrhea) is subdivided into malabsorption syndromes and maldigestion. In malabsorption syndromes, damage or loss of absorptive capacity occurs while maldigestion is caused by loss of digestive function.

Inflammatory diarrhea (exudative diarrhea) occurs with leukocytosis and leukocytes in stool. Purulent material and blood may also be present in stool. (4)

Secretory diarrhea, a type of watery diarrhea, is caused increased secretion of electrolytes, especially sodium and chlorine, in the intestinal lumen. This alters the intestinal epithelium’s ability to transport water and electrolytes and results in excess water. 2

Clinically, secretory diarrhea is not related to intake, so patients frequently say it is predominantly nocturnal. Consequently, it does not respond to fasting. Fecal volume neither decreases nor increases, 4 and its osmolarity is similar to that of plasma (fecal osmotic gap <50 mOsm/kg). 4 Furthermore, secretory diarrhea is voluminous with as much as 1 Liter in 24 hours. It is usually associated with electrolyte disorders such as hypokalemia and metabolic acidosis due to the concomitant loss of bicarbonate. 4

Causes of secretory diarrhea include infectious etiologies such as those caused by enterotoxins such as Vibrio cholerae and Escherichia coli. Surgical operations such as gastrectomies, intestinal resections, and vagotomies can also result in secretory diarrhea. Many substances can also cause this condition. They include luminal secretagogues such as bile acids and laxatives; circulating secretagogues such as digitalis, biguanides, and misoprostol; excess thyroid hormone; 5,6 and functional NETs that produce peptides such as gastrin, glucagon, and even vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) (as in the clinical case described in this report).

Within this context, NETs are neoplasms that occur relatively infrequently and whose clinical presentation varies. Initially, they may go unnoticed. However, they do have malignant and metastatic potential.

Eighty-five percent of all NETs originate in the gastrointestinal tract, while 10% occur in the lungs and manifest as bronchial carcinoids. 7 PNETs are mostly non-functional, but some can secrete hormones that lead to unique clinical syndromes such as vipomas.

Clinical case

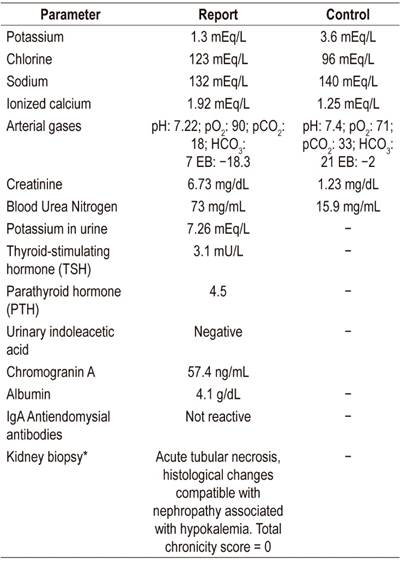

We present the case of a 37-year-old man who came to the emergency department after six months of 4 to 6 daily episodes of abundant diarrhea without mucus or blood. Episodes persisted despite fasting. The patient knew of no significant history but had come to the emergency department on several other occasions due to symptoms associated with dehydration and electrolyte disorders with severe hypokalemia and metabolic acidosis. He had required hospitalization on multiple occasions. At admission to our institution, he continued to suffer from large volume diarrhea, moderate dehydration and electrolyte disorder (Table 1).

Table 1 Principal tests before (report) and after (control) the use of octreotide during hospitalization.

*Taken and analyzed at a different medical institution.

mEq: milliequivalent; pO2: partial pressure of oxygen; pCO2: partial pressure of carbon dioxide; HCO3: bicarbonate; EB: base excess; 5-HIAA: 5-hydroxyindolacetic acid; TSH: Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone; PTH: parathyroid hormone; IgA: immunoglobulin A

The initial diagnostic stool and blood cultures for infectious causes were all negative. Despite multiple previous empirical antibiotic regimens, the patient had not improved. An HIV infection was also ruled out. He was evaluated by the gastroenterology service where he underwent endoscopy of the upper digestive tract and advanced colonoscopy of the ileum with biopsy. These tests ruled out inflammatory bowel disease and celiac disease. The latter was also excluded by a negative report for antiendomysial antibodies.

Diarrhea was classified as secretory (bulky and not related to food intake), persistent and becoming more intense leading to hypovolemic shock that required vasopressor support. Persistent severe hypokalemia required replacement with parenteral potassium and even caused acute kidney damage requiring renal replacement therapy. A functional NET was suspected and endocrinology support was requested.

Given the characteristics of the patient’s diarrhea, severe hypokalemia, metabolic acidosis with severe depletion of bicarbonate levels, and hypercalcemia, we requested VIP levels. However, this measurement was not available. Given the severity of the patient’s condition, a therapeutic test with 0.1 µg of octreotide of was administered subcutaneously every 8 hours.

Somatostatin analog therapy led to complete remission of diarrhea and resolution of shock and acute kidney injury in 48 to 72 hours. Renal replacement therapy was discontinued.

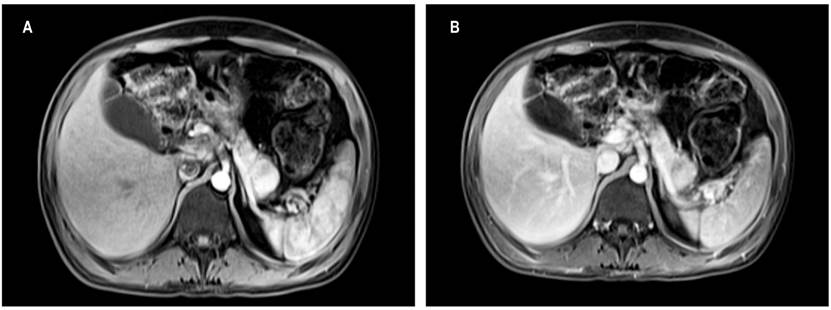

Diagnostic suspicion of vipoma was strengthened by the patient’s positive response to octreotide, so contrast-enhanced abdominal nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed. It showed a solid 22 mm hypervascular mass without metastatic lesions in the tail of the pancreas (Figure 1). The lesion was susceptible to surgical management, so the hepatobiliary surgery group performed a laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy plus splenectomy.

Figure 1 A. Contrast abdominal MRI. Solid 22 mm lesion in the tail of the pancreas with posterior enhancement by intravenous administration of contrast. Normal-sized pancreas. B. Solid 22 mm lesion in the tail of the pancreas, hypointense in T1, isointense in T2, hyperintense in diffusion, with enhancement after intravenous administration of contrast.

The histopathological study showed a grade 2 pancreatic NET (WHO) that measured 2.2 x 2 cm. Ki67 was 5% with a mitotic count of 2 mitoses for 10 high-power fields. No lymphovascular or perineural invasion was identified. During the postoperative period, octreotide was suspended in order to determine the success of the surgical procedure. Diarrhea did not recur, and the patient is currently symptom free.

Discussion

PNETs are infrequently occurring neoplasms that arise from multipotent stem cells in the epithelium of the pancreatic duct. 8 Fifty percent of them are non-functional or secrete peptides of low biological power such as pancreatic polypeptide (PP) or neurotensin. The other 50% are functional. Production of gastrin (gastrinoma) and insulin (insulinoma) is most common.

Insulinomas, clinically characterized by hypoglycemia with neuroglycopenic symptoms, are benign in up to 90% of cases. 7 Gastrinomas are characterized by peptic ulcers, severe diarrhea, and gastroesophageal reflux secondary to production of large amounts of gastrin. 7,8 Glucagonomas manifest through diabetes mellitus, thrombosis, depression and a skin rash known as migratory necrolytic erythema. This rash is red-brown, exfoliative and erythematous with superficial necrolysis and occurs mainly in the lower limbs. 5,6

Vipomas (or Verner-Morrison syndrome), first described in 1958, 7,8 are very rare. Their incidence is just 1 case per 10,000 people per year. They occur in non-insulin-producing pancreatic islets B and are usually large (72% measure more than 5 cm) and malignant (64% to 92%) at the time of diagnosis. 7,9 They generate profuse diarrhea, hypokalemia and classical achlorhydria due to the secretion of VIP in plasma. They also produce a 28 amino acid polypeptide that is widely distributed in the gastrointestinal tract and the brain. It relaxes vascular and visceral smooth muscle. All of this leads to the secretion of fluids and electrolytes in the intestinal lumen. 6,10,11

Secretory diarrhea, unlike osmotic diarrhea, persists during fasting. It is produced by increased secretion of water and electrolytes into the intestinal lumen to the point that it exceeds absorption capacity. 6 It is secondary to external factors such as VIP which stimulate production of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (AMP). 12

When in NETs secrete large quantities of VIP, patients often experience severe diarrhea, dehydration, erythema, and weight loss. VIP also promotes hepatic glycogenolysis that results in hyperglycemia, dilates peripheral systemic blood vessels, and inhibits hydrochloric acid secretion. 13

Imaging studies play important diagnostic roles since they make it possible to determine the extent of the lesion, involvement of neighboring organs, infiltration, and its relationship with vascular and nerve structures. Transabdominal ultrasound’s sensitivity varies between 20% and 86% depending on tumor size, but it is difficult to visualize tumors on the surface of the pancreas and duodenum. 14.Consequently, this test is useful as a guide for percutaneous biopsy, if indicated.

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is very useful for tumors located in the head of the pancreas and in the duodenal wall, 14 but it does not allow evaluation of extrapancreatic lesions given the potential of pNETs for malignancy. 15

On the other hand, computed tomography (CT) scans can locate the primary tumor and possible secondary lesions and has a sensitivity of 30% for tumors of 1 to 3 cm, and 95% for tumors larger than 3 cm. 14,16 Its performance improves notably with the use of multiphase techniques.

In the case of small lesions, gadolinium MRI has the highest sensitivity (91% to 94%). 14 Either multiphasic CT scans, MRI, or both can be used to plan the surgical approach and subsequent follow-up. 14,17

Essential initial treatment is correction of potentially fatal hydroelectrolytic disorders. Once the compromise has been defined by imaging, surgical resection is the next step. If a tumor cannot be completely removed, surgical reduction may have a palliative benefit especially when combined with treatment with somatostatin analogues which have antisecretory and antiproliferative effects, with tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as sunitinib, or with mTOR inhibitors such as everolimus. 11

In summary, the diagnostic approach to the patient described in this clinical case was partially limited because serum levels of VIP could not be processed. Nevertheless, diagnostic confirmation of a PNET was obtained histopathologically.

This case was first presented at Hospital Universitario Mayor Méderi and the Fundadores Clinic and is now being published to demonstrate our experience with this pathology which started with a relatively frequent reason for consultation: chronic diarrhea. Despite initial difficulties diagnosing the patient, a correct diagnosis was made, and he was treated correctly until resolution.

Conclusions

Vipoma is very rare: its incidence is 1 per 10,000 people per year. Profuse secretory diarrhea is the main symptom, and it frequently leads to hypokalemia, weight loss, and achlorhydria. This pathology may or may not be malignant, but it is always vitally important to recognize that this entity is potentially fatal given its severe hydro-electrolyte disturbances.

Surgical resection, the mainstay of treatment, has achieved complete remission of symptoms as occurred in the case described here. Our final objective is to encourage publication of cases with similar characteristics in order to unify early diagnosis approaches in a way that minimizes complications.

Referencias

1. Fernández F, Esteve E. Diarrea crónica. En: Montoro MA, García JC. Gastroenterología y hepatología: problemas comunes en la práctica clínica. Barcelona: Jarpyo Editores, 2ª edición; 2012. p. 125-146. [ Links ]

2. Pineda LF, Otero W, Arbeláez V. Diarrea crónica. Diagnóstico y evaluación clínica. Rev Col Gastroenterol. 2004;19(2):115-126. [ Links ]

3. Higuera-de la Tijera MF, Alexanderson-Rosas EG, Servín-Caamaño AI. Abordaje del paciente con diarrea crónica. Med Int Mex. 2010;26(6):583-589. [ Links ]

4. Juckett G, Trivedi R. Evaluation of chronic diarrhea. Am Fam Physician. 2011 15;84(10):1119-26. [ Links ]

5. Schiller LR. Secretory diarrhea. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 1999;1(5):389-97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11894-999-0020-8 [ Links ]

6. Thiagarajah JR, Donowitz M, Verkman AS. Secretory diarrhoea: mechanisms and emerging therapies. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12(8):446-57. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2015.111 [ Links ]

7. Vargas CC, Castaño R. Tumores neuroendocrinos gastroenteropancreáticos. Rev Col Gastroenterol. 2010;25(2):165-176. [ Links ]

8. Sívori E, Blanco D. Tumores neuroendocrinos del páncreas. Cirugía Digest. 2009;IV-489:1-9. [ Links ]

9. Dasari A, Shen C, Halperin D, Zhao B, Zhou S, Xu Y, et al. Trends in the Incidence, Prevalence, and Survival Outcomes in Patients With Neuroendocrine Tumors in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(10):1335-1342. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0589 [ Links ]

10. André R, Koessler T, Polet D, Roth A, Ritz M, Kherad O. VIPoma : a rare etiology of diarrhea with hypokalemia. Rev Med Suisse. 2018;14(592):289-293. [ Links ]

11. Cavalli T, Giudici F, Santi R, Nesi G, Brandi ML, Tonelli F. Ventricular fibrillation resulting from electrolyte imbalance reveals vipoma in MEN1 syndrome. Fam Cancer. 2016;15(4):645-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10689-016-9906-4 [ Links ]

12. Belei OA, Heredea ER, Boeriu E, Marcovici TM, Cerbu S, Mărginean O, et al. Verner-Morrison syndrome. Literature review. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2017;58(2):371-376. [ Links ]

13. Dimitriadis GK, Weickert MO, Randeva HS, Kaltsas G, Grossman A. Medical management of secretory syndromes related to gastroenteropancreaticneuroendocrine tumours. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2016;23(9):R423-36. https://doi.org/10.1530/ERC-16-0200 [ Links ]

14. Díez JJ, Iglesias P. Pruebas de imagen en el diagnóstico de los tumores neuroendocrinos. Med Clin (Barc). 2010;135(7):319-325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medcli.2009.04.048 [ Links ]

15. Anderson CW, Bennett JJ. Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2016;25(2):363-74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soc.2015.12.003. [ Links ]

16. Varas-Lorenzo MJ, Cugat E, Capdevila J, Sánchez-Vizcaíno E. Detección de tumores neuroendocrinos pancreáticos: 23 años de experiencia. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2019;84(1):18-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rgmx.2018.02.015 [ Links ]

17. Muros de Fuentes MA. Técnicas de imagen en el diagnóstico de los tumores neuroendocrinos gastroenteropancreáticos. Cir Andal. 2009;20:19-24. [ Links ]

Received: December 12, 2018; Accepted: March 26, 2019

texto en

texto en