Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista colombiana de Gastroenterología

Print version ISSN 0120-9957

Rev Col Gastroenterol vol.35 no.3 Bogotá July/Sept. 2020 Epub Mar 01, 2021

https://doi.org/10.22516/25007440.523

Review article

Irritable bowel syndrome. Relevance of antispasmodics

1Centro Médico Bustos Fernández (CMBF); Buenos Aires, Argentina

Irritable bowel syndrome is a disorder characterized by abdominal pain related to changes in bowel movements. Despite the progress made in the knowledge of its pathophysiology and the emergence of new therapeutic forms, antispasmodics have remained over time as an effective way to treat symptoms, especially pain. The purpose of this review is to search for scientific evidence on the use of antispasmodics in the treatment of irritable bowel symptoms.

Keywords: Irritable bowel syndrome; Antispasmodic; Abdominal pain

El síndrome de intestino irritable se caracteriza por la existencia de dolor abdominal relacionado con cambios en el ritmo evacuatorio. A pesar de los avances en el conocimiento de su fisiopatología y de la aparición de nuevas formas terapéuticas, los antiespasmódicos se han mantenido en el tiempo como una forma efectiva para el manejo de los síntomas de este síndrome, en especial para el dolor. Así pues, el propósito de esta revisión es la búsqueda de evidencia científica que soporte el uso de antiespasmódicos en el manejo de los síntomas del síndrome de intestino irritable.

Palabras clave: Síndrome de intestino irritable; antiespasmódicos; dolor abdominal

Introduction

Functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGID) are characterized by the appearance of predominant symptoms such as abdominal pain, bloating, distension or abnormal bowel habits (e.g. constipation, diarrhea, or both). FGIDs can be differentiated from other gastrointestinal disorders by their chronicity (6 months since symptom onset), current activity (symptoms within the last 3 months), frequency (symptoms, on average, at least 1 day per week), and the absence of obvious anatomical or physiological abnormalities identified through routine diagnostic tests, as deemed clinically appropriate 1.

FGIDs are classified into 5 different categories:

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

Functional Constipation (FC).

Functional Diarrhea (FD).

Functional abdominal bloating (FAB).

Unspecified annoyances.

IBS is the most frequent of these diseases, with a prevalence of 11.2% worldwide. These data are based on a meta-analysis of 80 studies in which 260 960 subjects were evaluated. According to said study, IBS prevalence rates are higher in women than in men, while younger people are more likely to be affected by it than those over 50 2.

In this context, IBS is a multifactorial disorder with a complex physiopathology. Factors that increase the risk of developing this syndrome may be genetic, environmental, or psychosocial, and aspects that trigger the onset or exacerbation of symptoms may include previous gastroenteritis, food intolerances and chronic stress 3.

Physiopathological mechanisms vary in each individual. They may include altered motility, visceral hyperalgesia, increased intestinal permeability, immune activation, altered microbiota, and alterations of the bowel-brain axis.

On the other hand, different psychological disorders have been associated with IBS 4,5. The most frequent complaints are anxiety, depression, emotional vulnerability, and self-esteem disorders 6. In this sense, the treatment of IBS begins by providing the patient with information about the characteristics of the syndrome, reassuring them about the benign natural history of the condition, and educating them about the usefulness and safety of diagnostic tests.

Treatment is planned according to the type of symptoms and their severity. Lifestyle modifications can improve these symptoms. These changes include engaging in physical activity, reducing stress, and improving sleep quality 7. Different treatments have been proposed for the management of IBS, which are based on controlling its main symptoms.

Diarrhea:

Constipation:

Abdominal pain:

Antispasmodics

Antispasmodics belong to a group of drugs that act on the intestinal smooth muscle. These substances prevent or interrupt the “spasm” or painful contraction 44. This is one of the mechanisms causing pain associated with IBS 23. According to their mechanism of action, they can be classified as follows:

Direct smooth muscle relaxing agents (mebeverine, papaverine-derived agents).

Anticholinergics (hyoscine butylbromide, hyoscine, hyoscyamine, levofloxacin, dicycloverine, butylscopolamine, trimebutine and cimetropium bromide).

Calcium channel blockers (pinaverium bromide, otilonium bromide, alverine, fenoverine, rociverine and pyrenzepine).

Direct smooth muscle relaxants reduce muscle tone and peristalsis. In this way, they can relieve intestinal pain without substantially affecting gastrointestinal motility. On the other hand, anticholinergics attenuate spasms or contractions in the intestine and, therefore, have the potential to reduce abdominal pain 23,24. Meanwhile, calcium antagonists relax the intestine by preventing calcium from entering intestinal smooth muscle cells. Since calcium triggers the cascade of events that triggers muscle contraction, its inhibition in the cells causes intestinal relaxation. This group of drugs can decrease the gastrocolic reflex and modify bowel transit time by reducing the motility rate.

Hyoscine N-butylbromide is the most widespread antispasmodic on the market, both as an over-the-counter and as a prescription drug. It is marketed as a single drug or combined with painkillers. This is an alkaloid derived from belladonna, whose pharmacological properties are due to its anticholinergic effects, which make it effective to reduce the frequency and intensity of spams in the gastrointestinal tract.

The ability of this drug to prevent motion sickness and vomiting is believed to be associated with vestibular inhibition in the central nervous system (CNS), which results in an inhibition of the vomit reflex. In addition, it has a direct action on the vomiting center, located in the reticular formation of the brain stem. This action makes it as an alternative to treat functional dyspepsia 25.

Antispasmodics in IBS

Different reviews and meta-analyses have been carried out to evaluate the management of IBS. In 2014, the American College of Gastroenterology published a review reporting that antispasmodics have been used for decades to treat IBS. This work was based on the concept that many of the symptoms of IBS are associated with intestinal smooth muscle spasms 16.

In said review, 25 controlled studies that evaluated 2154 patients were identified. Only three of these used standardized diagnostic criteria (Rome I, II) 26-28, while the other was conducted before the publication of the Rome criteria. This review shows that antispasmodic therapy has a statistically significant effect on the improvement of IBS symptoms, with a number needed to treat (NNT) of 5.

However, the effect of therapy with a single antispasmodic is variable and difficult to interpret, as there are only a small number of studies evaluating each of the 12 different drugs available for review. With respect to individual agents, otilonium bromide 26-28, hyoscine butylbromide 29-31, cimetropium bromide 32-34, pinaverium bromide 35 and dicyclomine hydrochloride 36 have showed beneficial effects with NNTs of 5, 3, 3, 3 and 4, respectively.

Indeed, a meta-analysis that assessed the effectiveness of smooth muscle relaxant agents in IBS concluded that these drugs are more effective than placebo in the treatment of this syndrome 21.

In a recent review on the treatment of IBS, other smooth muscle regulators were assessed 45.

Other smooth muscle regulators

Mebeverine

Mebeverine is a musculotropic antispasmodic that acts directly on the intestinal smooth muscle, so it is not associated with adverse anticholinergic effects. Results in individually randomized clinical trials differ. However, when analyzing the data available in the meta-analyses, no statistically significant differences are observed in favor of this drug regarding an overall improvement of symptoms, whether bloating or abdominal pain 21,37.

Otilonium bromide

Otilonium bromide is an antispasmodic with effect on muscarinic receptors. In addition, it is a calcium channel blocker and has been widely used for treating IBS. A meta-analysis published in 2012 grouped 4 randomized clinical trials that evaluated otilonium bromide versus placebo. There were statistically significant differences in favor of otilonium bromide with respect to the overall improvement of symptoms with an NNT of 7, and abdominal pain with an NNT of 8. The adverse effects of otilonium bromide were similar to those observed in the placebo group 21,38.

Alverine citrate

Alverine citrate is an antispasmodic calcium channel blocker, commonly associated with simethicone, used in the treatment of IBS. Several randomized clinical trials comparing its action to placebo use or conventional treatments have been published, showing statistically significant differences in favor of this agent in terms of overall improvement of symptoms and abdominal pain, with NNTs of 8 and 11, respectively.

Also, alverine citrate has been proven to generate a statistically significant improvement in abdominal distension and quality of life in individual studies conducted on IBS patients. Moreover, it appears to have a high safety profile, with adverse effects that do not differ from those reported in placebo groups 38,39.

Pinaverium bromide

Pinaverium bromide is also an antispasmodic calcium channel blocker used to treat IBS. It is usually administered alone or in combinations. In a meta-analysis conducted by Cochrane in 2011 that included 4 randomized clinical trials assessing the overall improvement of IBS symptoms in patients treated with this agent, statistically significant differences were found in the treatment group. In 3 of these randomized clinical trials, the efficacy of the drug to improve abdominal pain was also evaluated, finding significant differences in favor of pinaverium. Another meta-analysis published a year later, assessed the benefits of treatment of IBS based on the combination of pinaverium bromide and simethicone in two randomized clinical trials. One of them reported significant benefits of such combination regarding the improvement of abdominal distension, while the other one did not describe any advantages regarding overall improvement of symptoms and abdominal pain in comparison with the use of placebo.

Thus, both alone and in combination, otilonium bromide appears to be a safe drug, with adverse effects similar to those caused by placebo 21,37,38.

Trimebutine maleate

Trimebutine maleate is another calcium channel blocker used to treat IBS. In high concentrations, this drug reduces the amplitude of spontaneous contractions and action potentials. It also has an analgesic effect and acts as a weak μ opioid receptor (MOR) agonist. A meta-analysis published in 2001 reported statistically significant differences in favor of trimebutine regarding overall symptom improvement.

Meanwhile, another meta-analysis, previously cited in this review, describes significant advantages of using trimebutine for abdominal pain. However, studies assessing this drug have been carried out in a low number of patients, which explains why when including or excluding any publication from the analysis, the conclusions of the meta-analyses differ.

Regarding adverse effects, no differences versus placebo were reported in any of the publications included in this review 17-19.

Peppermint oil

Peppermint oil acts through several mechanisms: it is a calcium channel blocker, a κ-opioid receptor (KOR) antagonist, and a 5-HT3 antagonist. For this reason, besides having antispasmodic properties, it has other relevant effects on the treatment of IBS, such as the normalization of the orocecal transit time 40.

The available evidence on its use for treating IBS seems to be stronger than that of conventional antispasmodics. This is reported in a meta-analysis in which a significant improvement in abdominal pain and overall symptoms is observed, with an NNT of 4 and 3, respectively. Adverse effects such as nausea, vomiting, and heartburn were reported in this review. The latter seems to decrease when the drug is administered in three-layer tablets 40,41.

Eluxadoline

Eluxadoline is a μ and κ opioid receptor agonist, as well as an δ-opioid receptor (DOR) antagonist in the enteric nervous system. The agonist action of MORs promotes delayed gastric emptying, slowed transit constipation, and increased anal sphincter pressure.

On the other hand, the effects of DORs antagonists counteract the resulting constipation and increase the analgesia of MOR agonism 42. Eluxadoline is indicated in the treatment of IBS cases with diarrhea and has shown NNTs ranging from 8 to 33, with average values of 12.5.

A meta-analysis on the use of Eluxadoline, conducted in 2017 and in which 2427 patients were included, showed a statistically significant improvement in abdominal pain relief, stool consistency, overall symptoms, and IBS-related quality of life.

However, significant adverse effects were also reported, including nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and constipation. A higher incidence of pancreatitis and spasm in the sphincter of Oddi was also found, particularly in patients who had previously undergone a cholecystectomy. Due to these events, the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) contraindicates the use of eluxadoline in people with a history of biliary disorders, pancreatitis, severe liver failure or alcoholism, as well as in individuals who have undergone cholecystectomy 42,43.

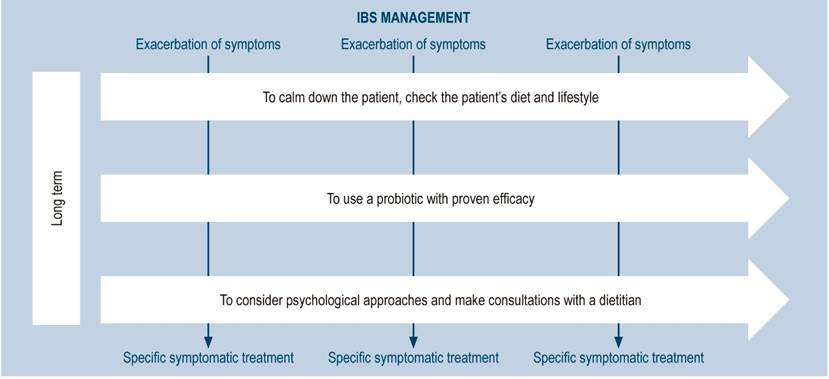

IBS treatments according to the WGO

In 2016, the World Gastroenterology Organisation (WGO) published the latest revision of the IBS guidelines, where issues regarding the treatment of this syndrome are addressed, and therapeutic options are proposed in accordance with the economic possibilities of the population 44.

Low economic level

General measures: providing the patient with information, reassuring them, reviewing their diet and lifestyle.

Symptomatic treatment:

Middle economic level

A quality probiotic with proven efficacy is added to the treatment mentioned above.

High economic level

Psychiatric drugs, psychological treatments, consultations with specialized dietitians and specific pharmacological agents (lubiprostone, linaclotide, rifaximin) can be added.

These data make it clear that the group reviewing these guidelines proposes the use of the most locally available antispasmodics as the first line of treatment 44.

These guidelines propose a scheme to treat IBS, which includes a specific symptomatic treatment depending on the type and intensity of the symptom, as well as on the availability of the drug (Figure 1).

On the other hand, the guidelines of the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) report a significant improvement in IBS symptoms when using antispasmodics. However, they point out that the use of these drugs is limited since most of them are not marketed in the United States 46.

In 2019, the latest meta-analysis assessing different therapies for the treatment of IBS was published. Soluble fiber, antispasmodic drugs and neuromodulators of the gut-brain axis were included. Regarding antispasmodics, it was concluded that the evidence supporting the use of peppermint oil is the most convincing and significant 46.

Conclusions

The treatment of IBS has different levels of complexity. With that in mind, antispasmodics continue to gain relevance in the management of this syndrome, supported by several scientific evidence. Beyond the fact that greater knowledge of the physiopathology of the disease has made it possible to find new therapeutic options, the use of these medications continues to be valid as a specific symptomatic treatment.

REFERENCES

1. Lacy BE, Mearin F, Chan L, Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Simren M, Spiller R. Bowel Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(6):1393-1407. http://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.031 [ Links ]

2. Lovell RM, Ford AC. Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10(7):712-721.e4. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2012.02.029 [ Links ]

3. Camilleri M, Lasch K, Zhou W. Irritable bowel syndrome: methods, mechanisms, and pathophysiology. The confluence of increased permeability, inflammation, and pain in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;303(7):G775-G785. http://doi.org/10.1152/ajpgi.00155.2012 [ Links ]

4. Drossman DA, McKee DC, Sandler RS, Mitchell CM, Cramer EM, Lowman BC, Burger AL. Psychosocial factors in the irritable bowel syndrome. A multivariate study of patients and nonpatients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1988;95(3):701-8. http://doi.org/10.1016/s0016-5085(88)80017-9 [ Links ]

5. Blewett A, Allison M, Calcraft B, Moore R, Jenkins P, Sullivan G. Psychiatric disorder and outcome in irritable bowel syndrome. Psychosomatics. 1996;37(2):155-160. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0033-3182(96)71582-7 [ Links ]

6. Drossman DA. Do psychosocial factors define symptom severity and patient status in irritable bowel syndrome?. Am J Med. 1999;107(5A):41S-50S. http://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00081-9 [ Links ]

7. Johannesson E, Simrén M, Strid H, Bajor A, Sadik R. Physical activity improves symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(5):915-922. http://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2010.480 [ Links ]

8. Rao AS, Wong BS, Camilleri M, Odunsi-Shiyanbade ST, McKinzie S, Ryks M, Burton D, Carlson P, Lamsam J, Singh R, Zinsmeister AR. Chenodeoxycholate in females with irritable bowel syndrome-constipation: a pharmacodynamic and pharmacogenetic analysis. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(5):1549-58, 1558.e1. http://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.052 [ Links ]

9. Biesiekierski JR, Newnham ED, Irving PM, Barrett JS, Haines M, Doecke JD, Shepherd SJ, Muir JG, Gibson PR. Gluten causes gastrointestinal symptoms in subjects without celiac disease: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(3):508-14; quiz 515. http://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2010.487 [ Links ]

10. Vázquez-Roque MI, Camilleri M, Smyrk T, Murray JA, Marietta E, O’Neill J, Carlson P, Lamsam J, Janzow D, Eckert D, Burton D, Zinsmeister AR. A controlled trial of gluten-free diet in patients with irritable bowel syndrome-diarrhea: effects on bowel frequency and intestinal function. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(5):903-911. http://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2013.01.049 [ Links ]

11. Moayyedi P, Quigley EM, Lacy BE, Lembo AJ, Saito YA, Schiller LR, Soffer EE, Spiegel BM, Ford AC. The Effect of Dietary Intervention on Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2015;6(8):e107. http://doi.org/10.1038/ctg.2015.21 [ Links ]

12. Wong BS, Camilleri M, Carlson P, McKinzie S, Busciglio I, Bondar O, Dyer RB, Lamsam J, Zinsmeister AR. Increased bile acid biosynthesis is associated with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10(9):1009-15. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2012.05.006 [ Links ]

13. Ford AC, Quigley EM, Lacy BE, Lembo AJ, Saito YA, Schiller LR, Soffer EE, Spiegel BM, Moayyedi P. Efficacy of prebiotics, probiotics, and synbiotics in irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(10):1547-61. http://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2014.202 [ Links ]

14. Pimentel M, Lembo A, Chey WD, Zakko S, Ringel Y, Yu J, Mareya SM, Shaw AL, Bortey E, Forbes WP; TARGET Study Group. Rifaximin therapy for patients with irritable bowel syndrome without constipation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(1):22-32. http://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1004409 [ Links ]

15. Lembo A, Pimentel M, Rao SS, Schoenfeld P, Cash B, Weinstock LB, Paterson C, Bortey E, Forbes WP. Repeat Treatment With Rifaximin Is Safe and Effective in Patients With Diarrhea-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2016;151(6):1113-1121. http://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.08.003 [ Links ]

16. Ford AC, Moayyedi P, Lacy BE, Lembo AJ, Saito YA, Schiller LR, Soffer EE, Spiegel BM, Quigley EM; Task Force on the Management of Functional Bowel Disorders. American College of Gastroenterology monograph on the management of irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109 Suppl 1:S2-26. http://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2014.187 [ Links ]

17. Chapman RW, Stanghellini V, Geraint M, Halphen M. Randomized clinical trial: macrogol/PEG 3350 plus electrolytes for treatment of patients with constipation associated with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(9):1508-1515. http://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2013.197 [ Links ]

18. Drossman DA, Chey WD, Johanson JF, Fass R, Scott C, Panas R, Ueno R. Clinical trial: lubiprostone in patients with constipation-associated irritable bowel syndrome--results of two randomized, placebo-controlled studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29(3):329-41. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03881.x [ Links ]

19. Chey WD, Drossman DA, Johanson JF, Scott C, Panas RM, Ueno R. Safety and patient outcomes with lubiprostone for up to 52 weeks in patients with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35(5):587-599. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04983.x [ Links ]

20. Omer A, Quigley EMM. An update on prucalopride in the treatment of chronic constipation. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2017;10(11):877-887. http://doi.org/10.1177/1756283X17734809 [ Links ]

21. Poynard T, Regimbeau C, Benhamou Y. Meta-analysis of smooth muscle relaxants in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15(3):355-361. http://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.00937.x [ Links ]

22. Ford AC, Quigley EM, Lacy BE, Lembo AJ, Saito YA, Schiller LR, Soffer EE, Spiegel BM, Moayyedi P. Effect of antidepressants and psychological therapies, including hypnotherapy, in irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(9):1350-65. http://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2014.148 [ Links ]

23. Spiller R, Aziz Q, Creed F, Emmanuel A, Houghton L, Hungin P, Jones R, Kumar D, Rubin G, Trudgill N, Whorwell P; Clinical Services Committee of The British Society of Gastroenterology. Guidelines on the irritable bowel syndrome: mechanisms and practical management. Gut. 2007;56(12):1770-98. http://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2007 [ Links ]

24. Lembo T, Rink R. Current pharmacologic treatments of irritable bowel syndrome. participate (international foundation for functional gastrointestinal disorders). N Engl J Med 2002;11:1-4. [ Links ]

25. Bouin M, Lupien F, Riberdy-Poitras M, Poitras P. Tolerance to gastric distension in patients with functional dyspepsia: modulation by a cholinergic and nitrergic method. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18(1):63-68. http://doi.org/10.1097/00042737-200601000-00011 [ Links ]

26. Clavé P, Acalovschi M, Triantafillidis JK, Uspensky YP, Kalayci C, Shee V, Tack J; OBIS Study Investigators. Randomised clinical trial: otilonium bromide improves frequency of abdominal pain, severity of distention and time to relapse in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34(4):432-42. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04730.x [ Links ]

27. Glende M, Morselli-Labate AM, Battaglia G, Evangelista S. Extended analysis of a double-blind, placebo-controlled, 15-week study with otilonium bromide in irritable bowel syndrome. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14(12):1331-1338. http://doi.org/10.1097/00042737-200212000-00008 [ Links ]

28. Mitchell SA, Mee AS, Smith GD, Palmer KR, Chapman RW. Alverine citrate fails to relieve the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16(6):1187-1195. http://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01277.x [ Links ]

29. Nigam P, Kapoor KK, Rastog CK, Kumar A, Gupta AK. Different therapeutic regimens in irritable bowel syndrome. J Assoc Physicians India. 1984;32(12):1041-1044. [ Links ]

30. Ritchie JA, Truelove SC. Treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with lorazepam, hyoscine butylbromide, and ispaghula husk. Br Med J. 1979;1(6160):376-378. http://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.1.6160.376 [ Links ]

31. Schäfer E, Ewe K. The treatment of irritable colon. Efficacy and tolerance of buscopan plus, buscopan, paracetamol and placebo in ambulatory patients with irritable colon. Fortschr Med. 1990;108(25):488-92. [ Links ]

32. Centonze V, Imbimbo BP, Campanozzi F, Attolini E, Daniotti S, Albano O. Oral cimetropium bromide, a new antimuscarinic drug, for long-term treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1988;83(11):1262-1266. [ Links ]

33. Dobrilla G, Imbimbo BP, Piazzi L, Bensi G. Longterm treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with cimetropium bromide: a double blind placebo controlled clinical trial. Gut. 1990;31(3):355-8. http://doi.org/10.1136/gut.31.3.355 [ Links ]

34. Passaretti S, Guslandi M, Imbimbo BP, Daniotti S, Tittobello A. Effects of cimetropium bromide on gastrointestinal transit time in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1989;3(3):267-276. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.1989.tb00213.x [ Links ]

35. Virat J, Hueber D. Colopathy pain and dicetel. Prat Med. 1987;43:32-4. [ Links ]

36. Page JG, Dirnberger GM. Treatment of the irritable bowel syndrome with Bentyl (dicyclomine hydrochloride). J Clin Gastroenterol. 1981;3(2):153-156. http://doi.org/10.1097/00004836-198106000-00009 [ Links ]

37. Martínez-Vázquez MA, Vázquez-Elizondo G, González-González JA, Gutiérrez-Udave R, Maldonado-Garza HJ, Bosques-Padilla FJ. Effect of antispasmodic agents, alone or in combination, in the treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2012;77(2):82-90. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.rgmx.2012.04.002 [ Links ]

38. Ruepert L, Quartero AO, de Wit NJ, van der Heijden GJ, Rubin G, Muris JW. Bulking agents, antispasmodics and antidepressants for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(8):CD003460. http://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003460.pub3 [ Links ]

39. Ducrotte P, Grimaud JC, Dapoigny M, Personnic S, O’Mahony V, Andro-Delestrain MC. On-demand treatment with alverine citrate/simeticone compared with standard treatments for irritable bowel syndrome: results of a randomised pragmatic study. Int J Clin Pract. 2014;68(2):245-254. http://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.12333 [ Links ]

40. Khanna R, MacDonald JK, Levesque BG. Peppermint oil for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48(6):505-512. http://doi.org/10.1097/MCG.0b013e3182a88357 [ Links ]

41. Cash BD, Epstein MS, Shah SM. A Novel Delivery System of Peppermint Oil Is an Effective Therapy for Irritable Bowel Syndrome Symptoms. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61(2):560-571. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-015-3858-7 [ Links ]

42. Fragkos KC. Spotlight on eluxadoline for the treatment of patients with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2017;10:229-240. http://doi.org/10.2147/CEG.S123621 [ Links ]

43. Harinstein L, Wu E, Brinker A. Postmarketing cases of eluxadoline-associated pancreatitis in patients with or without a gallbladder. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47(6):809-815. http://doi.org/10.1111/apt.14504 [ Links ]

44. Hani A. Antiespasmódicos. Guía Latinoamericana de Dispepsia Funcional. Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam. 2014;44(sup2):S57-S60. [ Links ]

45. Bustos Fernandez LM, Hanna-Jairala I. Tratamiento actual del síndrome de intestino irritable. Una nueva visión basada en la experiencia y la evidencia. Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam 2019;49(4):381-393 [ Links ]

46. Quigley EM, Fried M, Gwee KA, Khalif I, Hungin AP, Lindberg G, Abbas Z, Fernandez LB, Bhatia SJ, Schmulson M, Olano C, LeMair A; Review Team: World Gastroenterology Organisation Global Guidelines Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Global Perspective Update September 2015. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50(9):704-13. http://doi.org/10.1097/MCG.0000000000000653 [ Links ]

Citation: Bustos-Fernández LM. Irritable bowel syndrome. Relevance of antispasmodics. Rev Colomb Gastroenterol. 2020;35(3):338-334. https://doi.org/10.22516/25007440.523

Received: March 10, 2020; Accepted: May 05, 2020

text in

text in