Rationale and theoretical framework

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a term used to describe two rare chronic inflammatory conditions of the gastrointestinal tract that mainly affect the colon and the small intestine: Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). IBD is characterized by multiple relapses; besides, an increased frequency of occurrence has been detected worldwide in recent years1,2. Its etiology is unknown, but it results from a complex interaction between the host’s genotype, intestinal microbiota and environmental factors, which trigger an alteration in the intestinal immune system response3. Despite CD has traditionally been considered an autoimmune disease, it does not meet the criteria to be considered as such4 and, therefore, some authors think it is actually an autoinflammatory disease5,6.

Historically, studies reporting the highest prevalence rates of IBD have been conducted in Scandinavian countries, the United Kingdom, and North America. IBD affects approximately 5 million people worldwide, including 1.4 million in the United States and about 3 million in Europe7. In this regard, a systematic review of epidemiological studies about IBD found a CD prevalence of 0.6-322, 16.7-318.5, and 0.88-67.9 cases per 100,000 people in Europe, North America, and Asia, respectively. Also, an increase in its incidence over time has been described in 75% of CD studies8. In addition, a recent systematic review that included 147 studies reported high prevalence rates of CD in Europe (where the highest prevalence was found in Germany with 322 cases per 100,000 people) and North America (being the highest prevalence found in Canada with 319 cases per 100,000 people), which have remained stable9. However, population-based studies conducted since 1990 have shown an increase in the incidence and prevalence of CD in developing countries from Asia and South America such as Brazil, Mexico, and Colombia9-13.

In Colombia, CD has been found to be less frequent than UC: in 1991, in one of the first studies published in the country about this topic, and that included 108 patients diagnosed with IBD (98 with UC and 10 with CD) between 1968 and 1990 in Bogota (Colombia), a UC/CD ratio of 9.8:1 was described14. Then, in 2010, a study conducted at the Hospital Pablo Tobón Uribe in Medellín (Colombia) found that out of 202 patients diagnosed with IBD between 2001-2009, only 15.8% were CD cases, while 80.7% had UC (classifying the type of IBD was not possible in 3.5% of the study population), that is, a UC/CD ratio of 5.1:115. In addition, in a recent work conducted at the same hospital, a UC/CD ratio of 3.0:1 was found, since out of 649 patients with IBD, 478 had UC (73.7%), 159 had CD (24.5%). and in 12 (1.8%) it was not possible to determine the form of IBD; besides, in said study, CD was predominant in men 13. Other case series carried out in Colombia have also described a higher frequency of UC cases compared to CD cases16,17. These data show that in Colombia, more and more patients are diagnosed with CD in the context of IBD, which is a similar situation to what has been reported in developed countries18.

Because of its low prevalence, CD, unlike UC, meets the criteria to be considered an orphan disease. In Colombia, an orphan disease is defined as a severe, chronic debilitating and life-threatening disease with a prevalence (the number of individuals affected by a disease within a particular period of time) of less than 1 case per 5000 people (Law 1392 of 2010/Law 1438 of 2011)19.

CD usually occurs between the second and fourth decade of life, with a small additional peak in people aged 50-60 years20. Its diagnosis is based on the simultaneous evaluation of, on the one hand, clinical signs and symptoms and, on the other, alterations in endoscopic or radiological and biochemical and histopathological studies. Isolated alterations in the histopathology report are not enough to reach a CD diagnosis. In fact, the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation, in their recently published guidelines on CD, has confirmed that there is not a “gold standard” for the diagnosis of CD, and that genetic or serological tests should not be used for diagnosing it21,22. Clinically, CD is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the gastrointestinal tract that mainly affects the colon and the small intestine; however, it can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract from the mouth to the perianal area. It can also affect organs outside the gastrointestinal tract, and its clinical course is variable with alternating periods of activity and remission of symptoms. CD produces a segmental, asymmetric and transmural inflammation, and, from a clinical perspective, is a heterogeneous, insidious and progressive disorder. Depending on the severity, location and behavior of CD, the most common symptoms and clinical signs are abdominal pain, diarrhea, gastrointestinal bleeding, and weight loss1. Smoking, living in urban areas, exposure to antibiotics, and oral contraceptive use have been described as risk factors for CD23.

When performing a physical examination in these patients, signs of systemic toxicity, dehydration, malnutrition, anemia and malabsorption, as well as abdominal pain or palpable abdominal masses must be looked for. Physical examination of the perianal area is mandatory since perianal involvement occurs in up to one third of patients1. The most frequent laboratory findings are anemia, thrombocytosis, hypoalbuminemia, and high C-reactive protein (CRP) levels; however, the latter does not correlate well with endoscopic findings and in one third of patients, CPR levels never increase21,24. Fecal biomarkers such as calprotectin have been correlated with inflammatory activity by neutrophils in the intestine and are being used as a screening test with high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of IBD25. In this regard, it has been reported that patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) symptoms and with a fecal calprotectin concentration <40 μg/g, have a 1% chance of having IBD26. On the other hand, between 60% and 70% of patients with CD may have elevated antimicrobial antibody levels, being anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCA) the most prevalent; somehow, the sensitivity and specificity of these antibodies are too low to reach a CD diagnosis27.

Endoscopic findings reported by means of ileocolonoscopy are key to the diagnosis of CD. Typical findings include the presence of multiple inflammatory aphthous ulcers with segmental involvement, associated with longitudinal and serpentiginous ulcers. Additionally, the presence of perianal involvement, fistulas, ileitis, and strictures supports the diagnosis of CD22,28. In case of negative results in the ileocolonoscopy, but clinical suspicion of CD, small bowel capsule endoscopy is indicated in the absence of obstructive symptoms or known stenosis21. Histologically, inflammatory involvement is chronic, focal, discontinuous, and transmural. Epithelioid granuloma is the histological marker of CD, but it is only found in 15% of mucosal biopsies and 70% of surgical specimens1,29. Imaging studies such as magnetic resonance (MR) enterography and Computed tomography (CT) enterography are useful to reach a CD diagnosis, as well as to determine its extent and rule out complications such as strictures and fistulas; furthermore, they can be useful for follow-up purposes, since they can be used to measure the activity of the disease and the patient’s response to treatment30. It should be noted that MR enterography is preferred due to the lower radiation exposure it involves compared to CT enterography. Finally, the use of pelvic MRI is recommended for the study of perianal and fistulizing CD30.

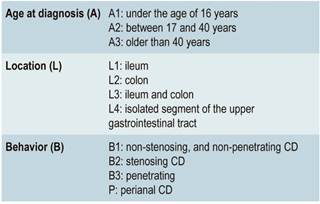

Once the diagnosis has been reached, patients with CD should be phenotyped according to the Montreal classification31 in order to determine its location and clinical behavior. The location of the disease tends to be stable, but its behavior usually changes over time32.

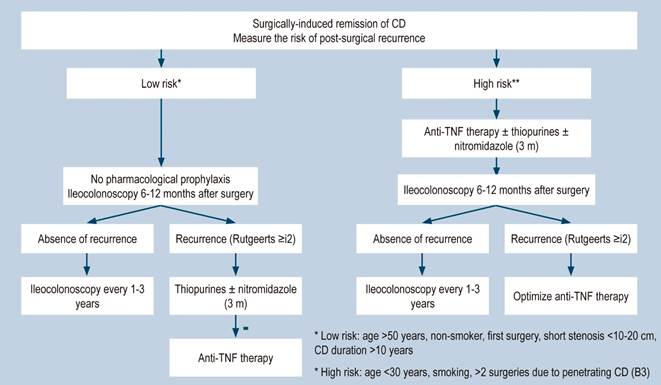

A systematic review that included population-based studies found that the risk of surgery in patients with CD was 16.3%, 33.3%, and 46.6% at 1, 5, and 10 years of follow-up, respectively33. Unfortunately, CD cannot be cured with surgery: 50% of patients report clinical recurrence, 80%, endoscopic recurrence, and 30% require additional surgical management34. In addition, patients with CD are classified based on the risk of developing complications35. On the other hand, conditions that are associated with a poor prognosis in these patients include isolated location in the ileum or location in the ileum and colon, severe involvement of the small bowel or extensive involvement of the upper gastrointestinal tract, perianal lesions, severe rectal involvement, deep ulcers on colonoscopy, history of intestinal surgical resections, stenosing and penetrating behavior of the disease, the need for steroid use at the time of diagnosis, young age at diagnosis (<30 years) and being a smoker35,36.

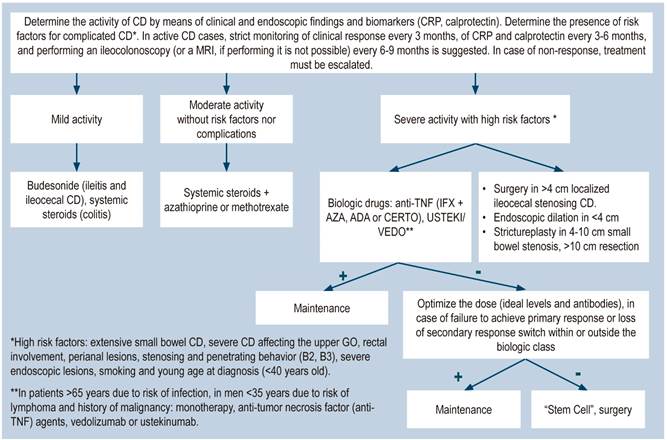

The current objective of CD treatment is to induce and maintain the clinical and endoscopic remission of its symptoms in order to prevent its progression37,38. In the past, the goal was to control CD symptoms; however, they do not correlate with the inflammatory activity of the involved areas. Therefore, the lack of this correlation has shifted the treatment goals to achieve a “deep remission”, which includes both, clinical remission, and endoscopic healing1,39. When “deep remission” is achieved, there are fewer relapses, fewer surgeries, and less intestinal damage (38). Considering that deep remission is the current goal of treatment for CD, therapeutic targets (“Treat to Target”) have been identified40, and recent studies suggest that this strategy, besides being cost-effective, should have an impact on CD progression and improve outcomes in these patients41.

Drugs used in the treatment of CD aim to attenuate or reduce the chronic abnormal inflammatory activity by acting on the immune pathways of the disease1. It should be noted that none of the available treatment cures CD. Drugs used to treat CD include 5-aminosalicylates (5-ASA); systemic (prednisone, prednisolone) or topical (budesonide) steroids; immunomodulators (azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, methotrexate); biological therapy (tumor necrosis factor-alpha [TNF-α] inhibitors): infliximab, adalimumab, and certolizumab pegol; anti-integrins: natalizumab, vedolizumab, anti-L12/23 p40 subunit, ustekinumab; probiotics, and antibiotics (ciprofloxacin, metronidazole). Surgical treatment is also available. Furthermore, the expiration of the patent of infliximab has allowed the introduction of its biosimilar37,42-44.

Given the complexity of CD, management by a multidisciplinary team is necessary, which, in addition to the gastroenterologist, includes the fundamental participation of a colon and rectal surgeon expert in the disease, as well as a nurse, a radiologist, a pathologist, a nutritionist and a psychologist, among others45.

The standard of care includes the education of patients and their families, the absolute prohibition of smoking and the vaccination of patients46-49.

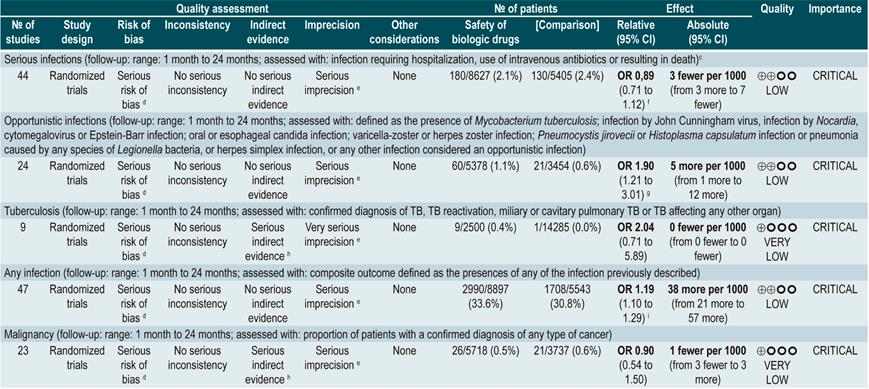

Once the CD diagnosis has been established, ruling out the presence of diseases that may recur or be exacerbated when starting immunosuppressive treatment (steroids, immunomodulators or biological therapy) is essential50. Therefore, performing some tests is required, including tuberculin test; chest x-rays; hepatitis B virus panel: hepatitis B surface antigen, HBsAb (hepatitis B surface antibody), anti-HBc or HBcAb (hepatitis B core antibody); HCV antibody (anti-HCV test); human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), varicella zoster, and Epstein-Barr virus tests51. On the other hand, a concern when using biological therapy is the risk of infection, serious infection, and opportunistic infection. A serious infection occurs when the patient requires hospitalization or intravenous administration of antibiotics, and an opportunistic infection is caused by the weakening of the immune system, since it does not occur in immunocompetent individuals. Some examples of this type of infection include those caused by Clostridium difficile, mycobacterium, candida, cytomegalovirus, and varicella zoster50. Per se, CD activity also increases the risk of infections: when the disease is moderate-severe, the risk of serious disease increases twofold. For every 100 points of activity, the risk of serious infection and opportunistic infections increases by 39% and 31%, respectively51.

CD treatment involves an induction pharmacological regimen and then a maintenance pharmacological regimen. The choice of medication depends on the severity of the disease, the use of the medication in any previous treatment, and the presence of risk factors for developing complications35,37,52,53.

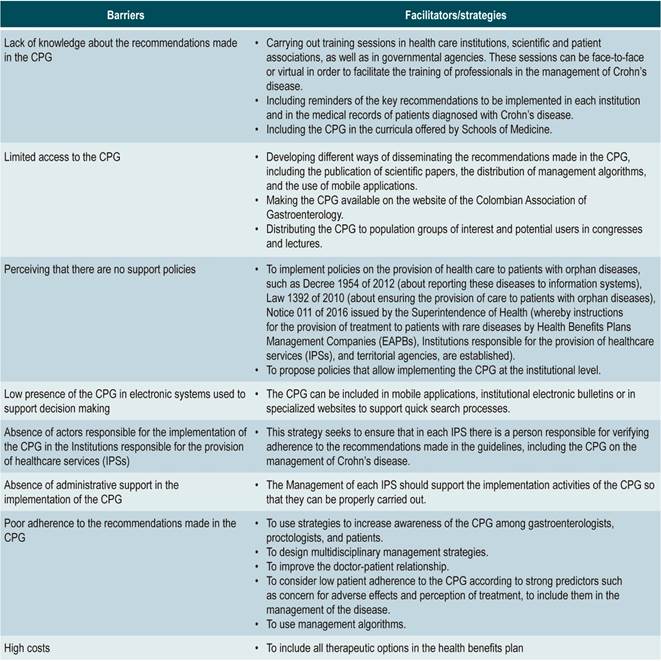

Currently, there are several pharmacological therapies and surgical interventions to treat CD; however, and despite there are multiple randomized studies, some clinical conditions related to CD are still managed based on clinical judgment and experts’ opinion, which has been reflected in the existing conceptual differences regarding the treatment of these patients. Taking this into account, and the fact that CD is a chronic disease that mostly affects young people, as well as the resulting social and economic implications, the development by multidisciplinary groups of a clinical practice guideline (CPG) for the treatment of this disease based on the best and more recent available evidence is necessary to unify the criteria for the successful management of CD in Colombia. The wide variety of clinical scenarios and the diverse individual and social circumstances of these patients difficult the provision of medical care to them, which is one of the justifications for developing this GPC with the aim of reducing the unjustified variability of criteria for treating patients with CD. Although the concepts presented here are based on the best published scientific evidence, this CPG provides recommendations that shall be used according to the clinical judgment of the treating physician.

Objectives

This CPG was developed taking into account the following objectives:

To make evidence-informed recommendations for the treatment of patients with CD.

To contribute to the timely and safe treatment of patients with CD, considering the minimization of the need for hospitalization and sequelae.

To support decision makers in the development of policies for the proper management of CD.

Population

Population groups to be considered

Patients older than 16 years diagnosed with CD, regardless of the time of progression and the clinical stage of the disease, nor the health care insurance plan they are enrolled in.

Users of the clinical practice guideline

This CPG is intended for health care workers such as gastroenterologists, colorectal surgeons (coloproctologists), gastrointestinal surgeons, internal medicine specialists, family medicine specialists, general practitioners, as well as for patients and other health care professionals interested in the management of CD.

Funding of the clinical practice guideline

The development of this GPC was funded by the Colombian Association of Gastroenterology.

Editorial independence statement

The funding organization provided support to the group in charge of the development of the guidelines (GDG) during its development, thus guaranteeing that its contents are transferable and applicable in the Colombian context. The scientific research work, as well as the recommendations included in this document were carried out independently by the GDC. The funding organization did not have any influence on the contents of the CPG.

Scope

This CPG is directly intended for health care professionals who provide medical care to patients with CD, but it is also indirectly intended for health care decision makers in the context of health care provision, and health insurance companies, health care payers, and health care policy makers. This CPG is intended to establish guidelines for the treatment of CD, and its scope is limited to the target population.

Health care provision setting

This CPG aims to help medical care providers treating patients older than 16 years with CD in any level of care. It should be noted that the management of very specific conditions by health care professionals involved in the care of patients with CD requires specific recommendations, which are beyond the scope of this guideline.

This CPG provides recommendations for all levels of care in which patients with CD are treated. It also provides health care professionals with enough information to provide guidelines for the proper management of CD.

Main clinical aspects

Clinical aspects addressed by the CPG:

The CPG will address the medical and surgical treatment of CD and poor prognostic factors in patients older than 16 years.

Aspects related to the diagnosis of the disease or the rehabilitation of these patients will not be addressed since, due to their length and complexity, these should be addressed in separate CPGs to be developed de novo (NICE, 2010).

Guideline audit support

Review criteria and assessment indicators have been included in the development of the CPG.

Updating the clinical practice guideline

Recommendations made in this guideline must be updated within the next three (3) years or sooner if new evidence modifying said recommendations becomes available. This process should be carried out by creating an expert panel responsible for making the necessary changes.

Glossary

Active disease: CD is clinically classified as mild, moderate, and severe. The severity of the disease is determined using the Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI). In most clinical trials, CD is classified depending on the score as follows: mild: 150-220; moderate: 220-450, and severe: >450.

Steroid-dependent Crohn’s disease:

patients in which reducing the steroid dose below the equivalent of prednisone 10 mg/day (budesonide 3 mg/day) within the first 3 months after being administered the steroids is not possible without experiencing disease recurrence; or

patients who relapse within the first 3 months after steroids are suspended.

total length of steroid therapy should not exceed 3 months.

Extensive disease: intestinal involvement >100 cm, regardless of CD location. The sum of inflammation areas alternating with non-involvement areas is included.

Localized disease: intestinal involvement of less than 30 cm.

Steroid refractory disease: patients with CD activity despite the administration of up to 1 mg/kg/day prednisone for 4 weeks.

Relapse: exacerbation of symptoms in a patient with CD who was in clinical remission, either if it occurs spontaneously or after medical treatment; a 70-point increase in the CDAI. Confirming the relapse with laboratory, endoscopic or imaging studies in the clinical practice is suggested.

Early relapse: exacerbation of symptoms in less than 3 months in a patient with CD in clinical remission and undergoing medical treatment.

Recurrence: recurrence of endoscopic lesions after undergoing surgical resection.

Clinical recurrence: recurrence of symptoms after performing the complete macroscopic resection of the disease, and after confirming the recurrence of endoscopic lesions. Confirming the presence of lesions is important, since there are conditions with symptoms that can mimic those of CD (bile salts malabsorption, motility disorders, bacterial overgrowth, among others).

Morphological recurrence: appearance of new CD lesions after performing the macroscopic resection of the disease, usually in the neo-terminal ileal stricture or in the anastomosis; it is usually detected through endoscopy, imaging studies or surgery. Endoscopic recurrence is classified according to the RUTGEERTS score: 0: no evident lesions. 1: less than 5 anastomotic aphthous lesions. 2: more than 5 apthous lesions with normal mucosa between the lesions. 3: diffuse aphthous ileitis with diffusely inflamed mucosa. 4: ileitis with ulcers, nodules, and/or strictures.

Clinical remission: CDAI <150 points. Confirming clinical remission by means of objective parameters based on laboratory (fecal calprotectin, CRP), endoscopic or imaging studies in the clinical practice is suggested.

Response to treatment: a change in the CDAI score, a ≥100 points decrease in the CDAI score.

Methodology

This section has been adapted from the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) template available in the Strengthening national evidence-informed guideline programs. A tool for adapting and implementing guidelines in the Americas document, published in 2018.

Composition of the group

The GDG was composed by experts in gastroenterology, colorectal surgery, gynecology, epidemiology, pharmaceutical chemistry, and public health. In addition, cooperation by the Colombian Cochrane STI (Sexually Transmitted Infections) Group was received by the GDG. The Cochrane STI Group performed the systematic search of the relevant literature, retrieved the full text of the studies and created the GRADE tables.

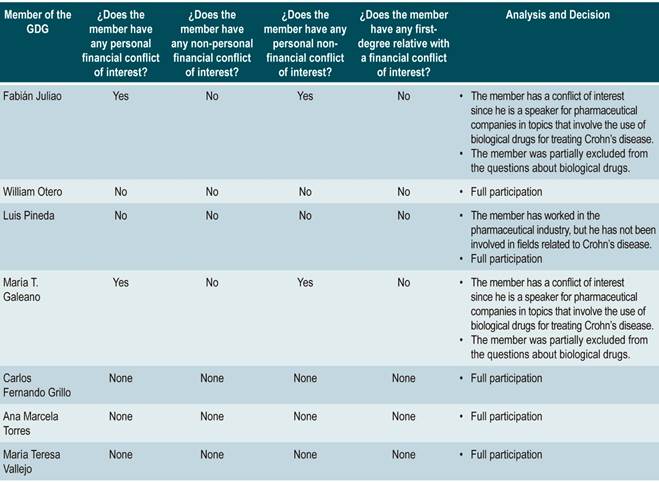

Conflicts of interest statement

Those who took part and are responsible for the making of the recommendations presented in this CPG shall state in writing and in advance any conflicts of interest regarding said recommendations.

An analysis of the conflicts of interest was carried out and, based on the conflict or conflicts stated, partial or full participation was decided. Two experts were excluded from the formulation process of recommendations related to biological drugs for they are speakers for several pharmaceutical companies on the use of these drugs for treating CD. This analysis is available in Annex 1.

Definition of the scope and objectives of the clinical practice guideline

The scope and objectives of this CPG were defined by the Colombian Association of Gastroenterology with the purpose of supporting health professionals that provide medical care to patients with CD, so that they can provide high quality, equitable, efficient, and homogeneous medical care to these patients. After conducting a literature review on CD, the GDG wrote a document considering the heterogeneity in clinical practice, the availability of new evidence, the existence of new therapeutic alternatives, the inadequate use of resources, and the quality problems found in clinical practice resulting from the health care provision system. The topics that were addressed and those who were not addressed, as well as the target population and main clinical aspects of the CPG were also defined.

Decision on the development or adaptation of the clinical practice guideline

The GDG conducted a systematic search of the literature in order to identify all Colombian and international CPGs addressing the management of patients with CD and that had a similar scope and objective to those proposed for this CPG. The quality of the CPGs retrieved was evaluated using the AGREE II tool54 and each document was graded independently by two raters in order to determine the overall quality of each guideline. According to the guidelines proposed by international CPG developers, once the grading process was completed, discrepancy levels for each guideline were assessed to identify the domains that required to be reviewed. This discrepancy was evaluated using the rating system proposed by the AGREE group54.

Once the overall quality of each guideline was determined and the domains that needed to be reviewed were identified, informal consensus meetings were held to establish the possibility of adapting or developing de novo the CPG. Bearing this in mind, the GDG used the criteria included in the CPG adaptation or de novo development decision matrix as input55.

The following aspects are considered in the decision matrix:

The scope and objective of the retrieved CPGs must be related to the scope and objectives of the CPG to be developed.

The CPGs retrieved were developed using evidence-based methodologies, have evidence tables and are less than 5 years old.

The CPGs must have a have an adequate score in terms of methodological quality and editorial independence when evaluated using the AGREE II tool.

The CPGs must be recommended by both raters.

Based on the results of the decision matrix, the GDG considered that none of the eligible CPGs met all the necessary criteria to be adapted, so the de novo development of the CPG was started.

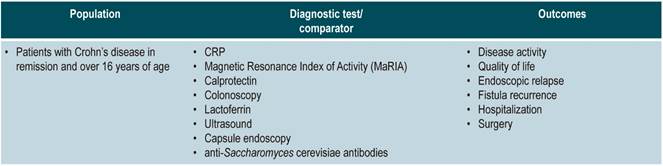

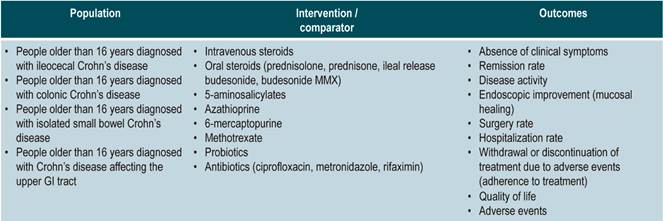

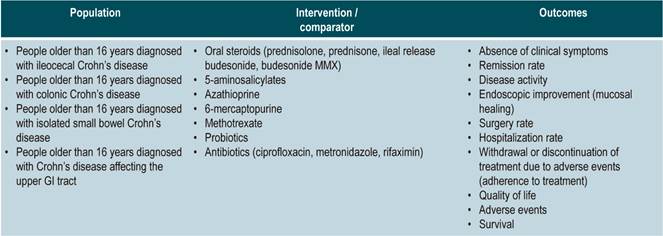

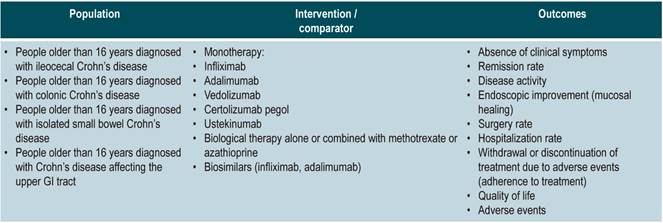

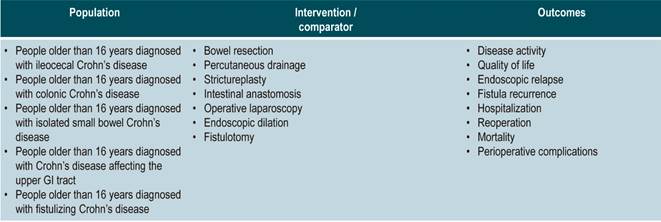

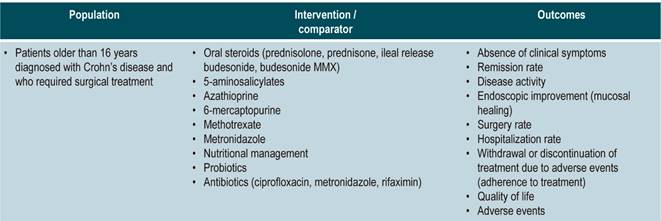

Formulation of the clinical questions of the clinical practice guideline

The GDG reviewed the relevant clinical aspects to be included in the CPG and, based on them, formulated basic questions which were then restructured according to the PICO (population, intervention, comparison, and outcome) framework. The resulting questions can be found in Annex 2.

Identification and grading of the clinical practice guideline outcomes

Literature search for the de novo development

The first step for the de novo development was conducting a search of systematic reviews in the following databases: MEDLINE (via Ovid) EMBASE (via embase.com) and Cochrane Library, which in turn includes the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database, the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) and the NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED).

Search strategies were developed and performed by the search coordinator of the Cochrane STI Group; the GDG contributed to this process too. For this purpose, identification forms of words related to the clinical questions were used to select controlled language and free language terms, which in turn allowed creating the search syntaxes for each database (Annex 4). No publication date or language restrictions were applied in the search. Classic and relevant studies about CD proposed by experts were also included for full analysis. Clinical questions that were not addressed by systematic reviews were answered by including primary studies.

Grading of the evidence

Evidence was graded according to the type of evidence. The systematic reviews (SR) that were retrieved were assessed using the AMSTAR checklist56; besides, the contents, quality and clinical relevance of each SR were evaluated to identify those with the highest methodological quality, which were finally included in the GPC. When there were no high-quality systematic reviews, primary studies were assessed using the risk of bias tool recommended by Cochrane57.

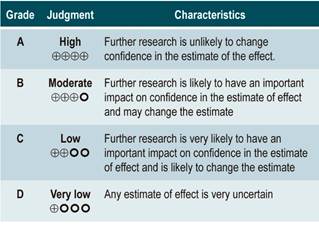

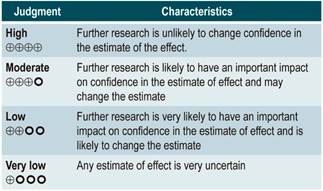

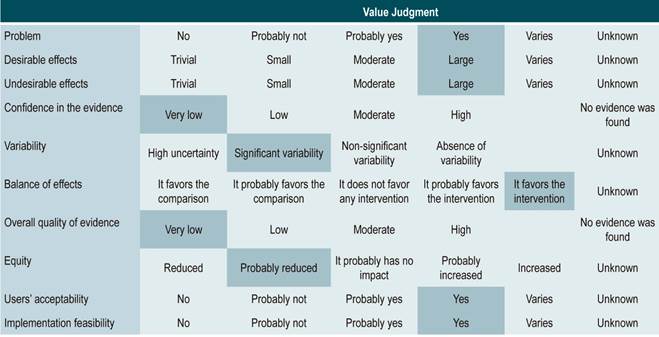

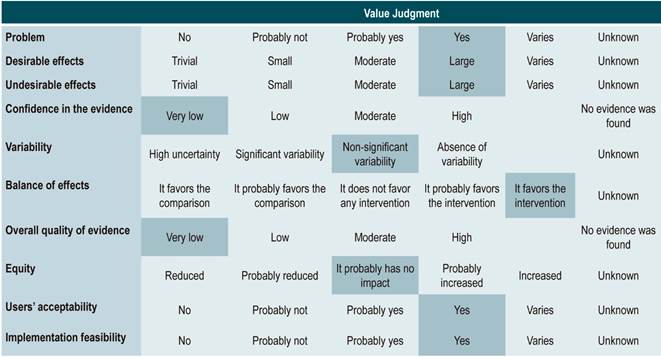

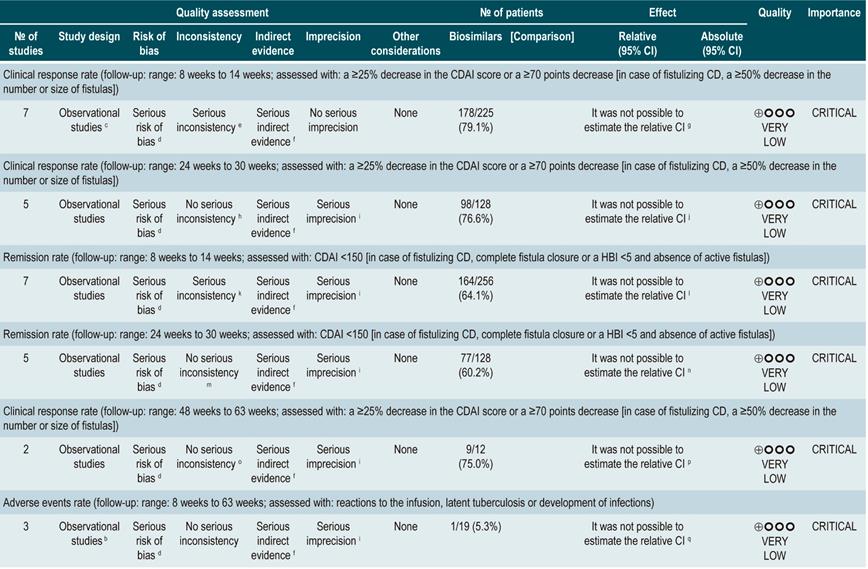

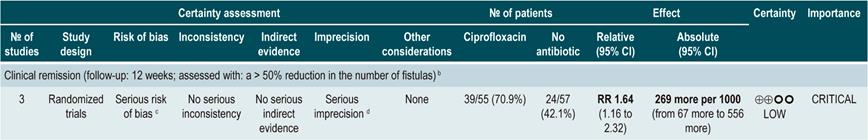

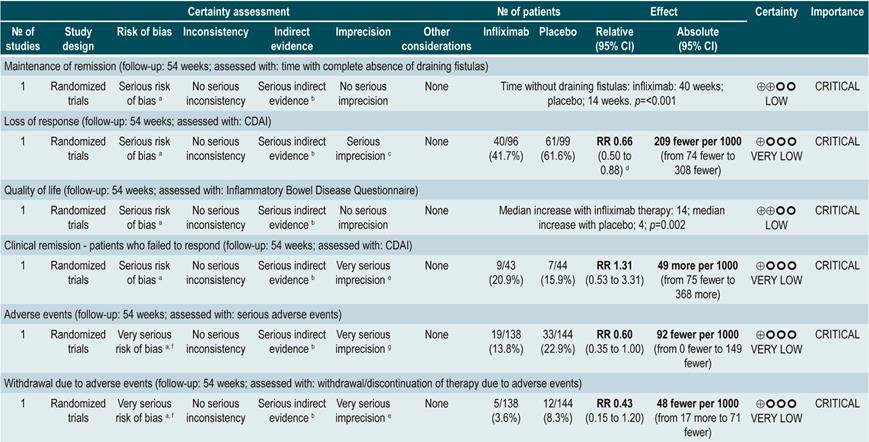

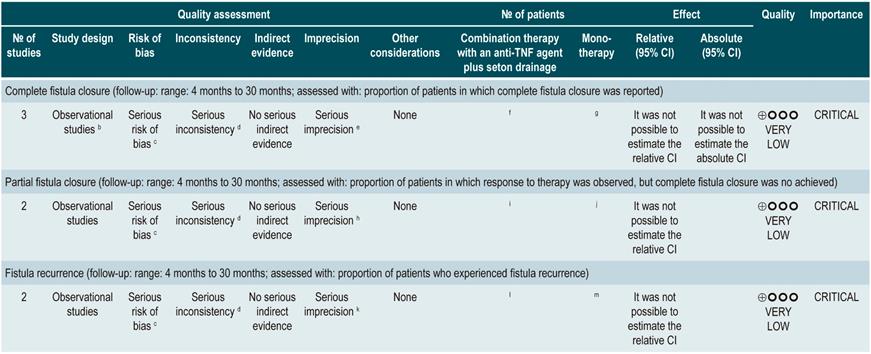

Evidence profiles were created using the www.guidelinedevelopment.org website to summarize the evidence found, and the levels of evidence were graded according to the GRADE classification, which grades the quality of the evidence in four levels58.

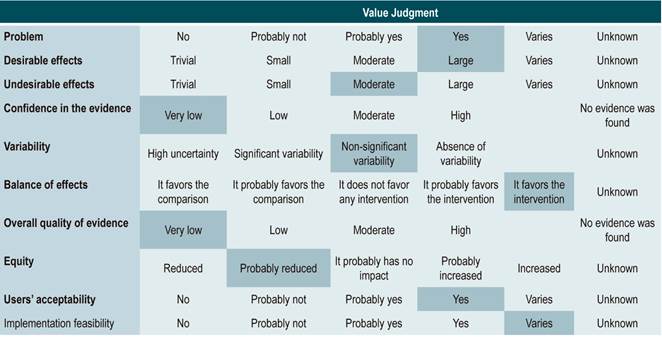

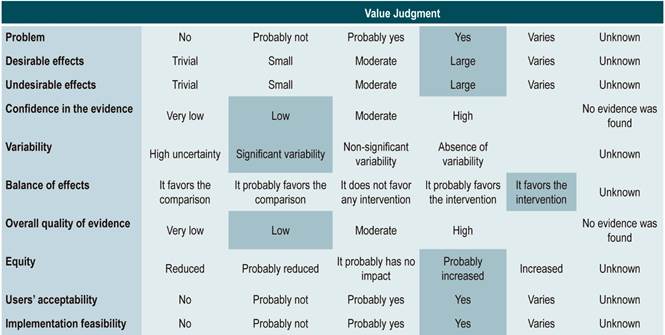

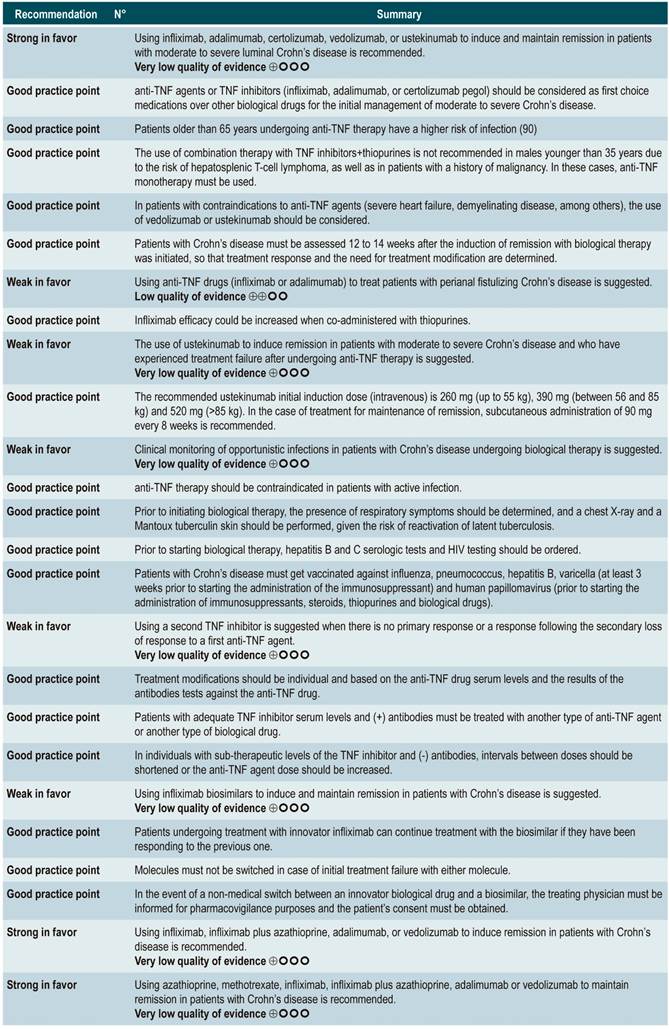

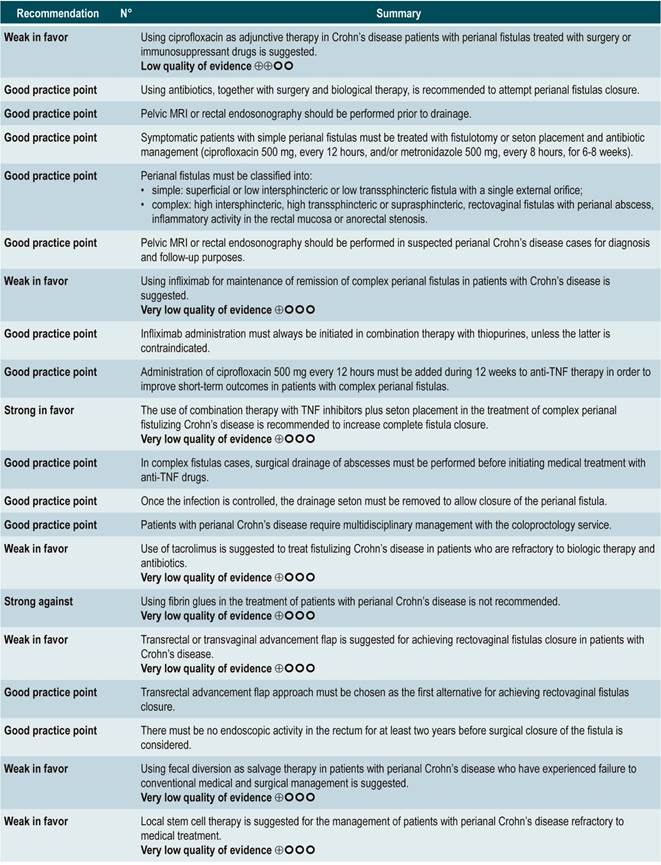

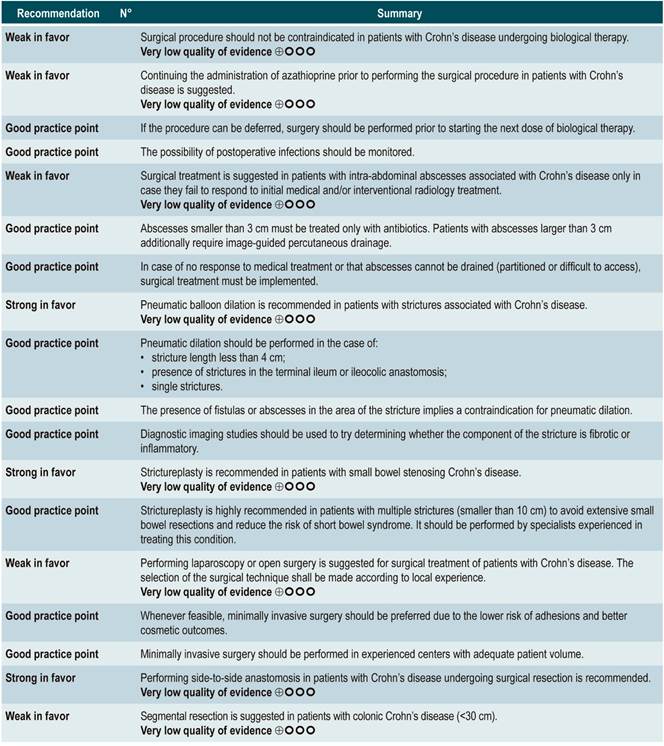

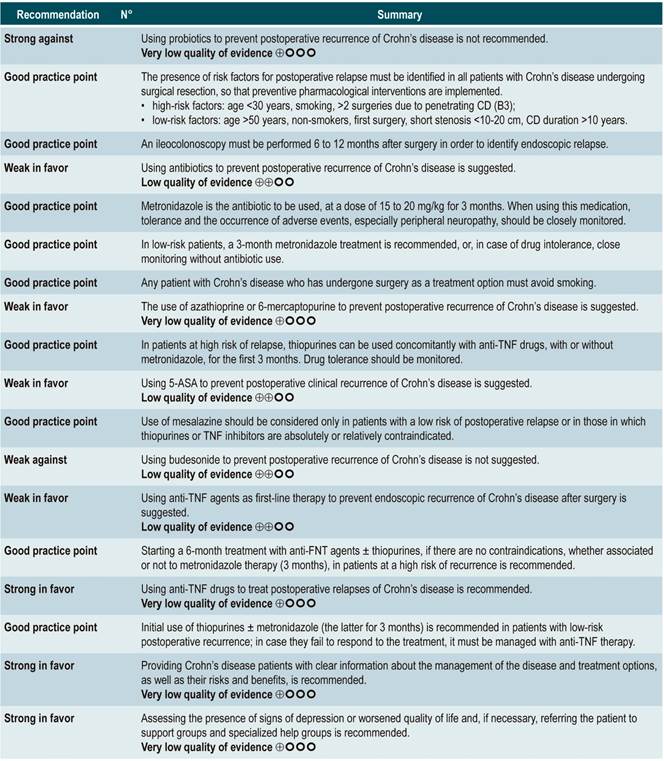

Grading the strength of the recommendations

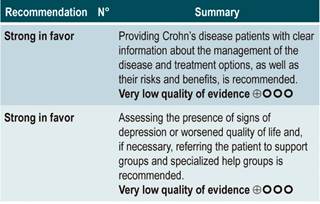

Recommendations were formulated in two steps. First, the GDG made the preliminary recommendations considering the risk-benefit balance, the preferences of patients, and the Colombian context. Then, the recommendations were discussed and adjusted in an expert panel with the representatives of users and patients. The strength of each recommendation was determined based on the level of evidence and other additional considerations that were fully reviewed by the GDG, the managing body of the CPG, and the expert panel taking into account the different scenarios of the Colombian context.

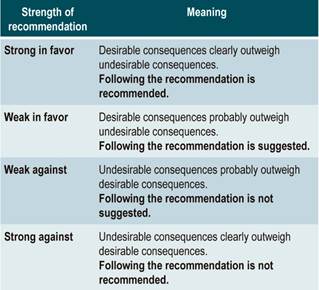

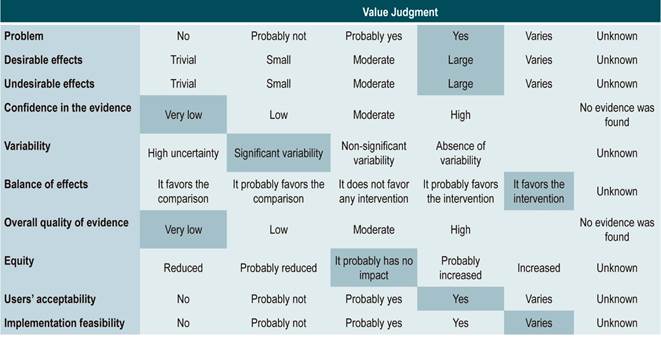

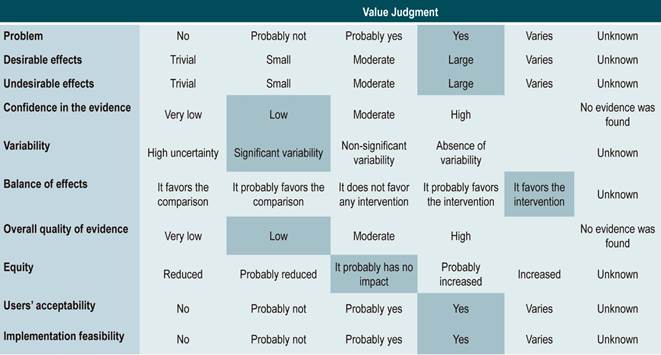

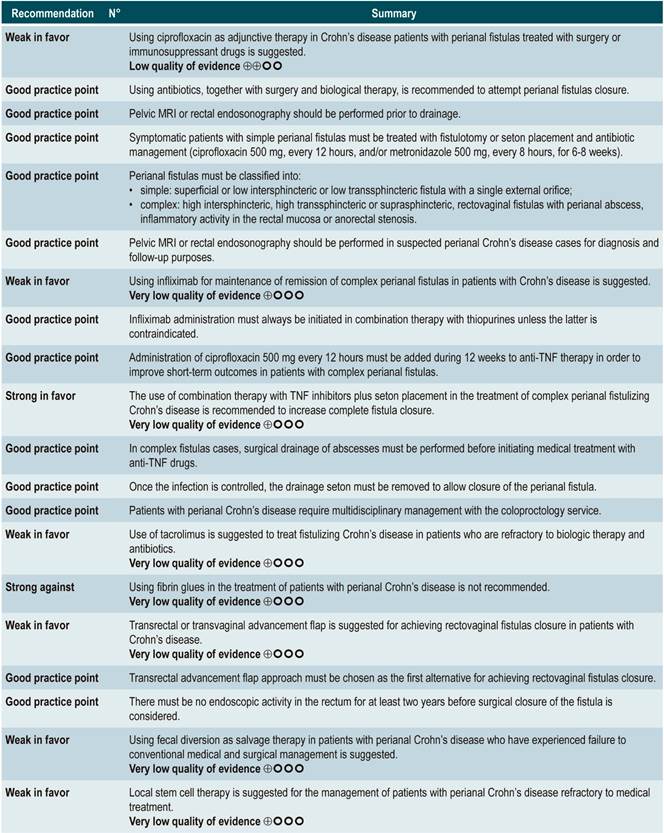

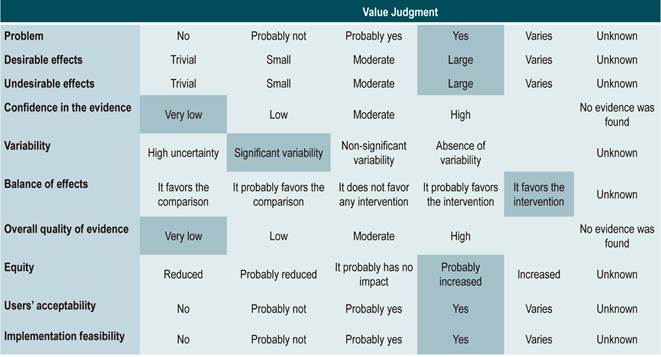

The GRADE methodology grades the strength of a recommendation as “Strong” or “Weak”. Once the risk-benefit balance, the quality of evidence, the values and preferences of patients, and the Colombian context were considered, the strength of each recommendation was determined using the following structure:

Finally, expert panel agreement with the recommendations that were suggested and the inclusion of the participants’ perspective in them was verified. All recommendations and their grades were voted on.

Good practices

Good practices are operational suggestions based on the experience of the GDG and the GRADE working groups where different stakeholders participated; although they are not evidence-based, they are part of the good diagnosis, treatment, or follow-up practices of patients. Good practices are intended to support the recommendations made in the CPG.

Inclusion of costs and preferences of patients

A cost-effectiveness assessment was not performed in the development of this CPG. The preferences of patients were identified through a systematic review, where the values and treatment preferences of patients and their perception of CD were assessed, which in turn helped strengthen the recommendations.

Cost-related considerations were not included in the development of this CPG given the variability of the Latin American context, so they are not included in the value judgment table of the recommendations. In addition, cost-influenced recommendations were not identified. Regarding preferences and values of patients, a search was performed, but it yielded only one study. However, given the disease, the management strategy and the target population, there are few recommendations that can be influenced by the preferences of parents or caregivers.

Formulation of questions by expert consensus

In the case of clinical questions in which no evidence was found or where evidence was controversial, the GDG made clinical practice recommendations based on their professional experience and good practices; these recommendations were submitted to formal consensus in the GRADE working groups.

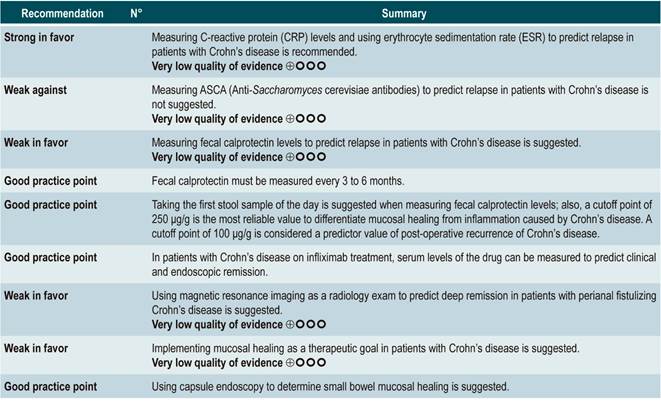

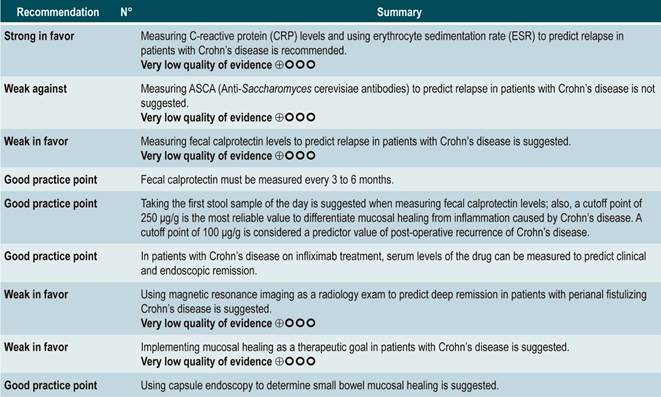

Question N° 1. What are the predictors of relapse of crohn’s disease in patients older than 16 years?

Summary of evidence

C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and ASCA

A systematic review (AMSTAR score 8/11) assessed the predictive ability of C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and ASCA in patients with CD who were in remission. The outcome of interest was the occurrence t of relapse, defined as having a CDAI score >150; the prognostic value was expressed using hazard ratios (HR) or risk ratios (RR)59.

There was heterogeneity among studies included in the review regarding the reporting of outcomes and the cut-off points assessed; thus, summarizing the evidence using meta-analysis techniques was not possible.

C-reactive protein: a cohort study performed a relapse prediction model based on the biological parameters of 101 patients with fistulizing, inflammatory or stenosing, intestinal or extraintestinal CD. Based on this model, it was established that, during the first year of follow-up, a CRP level greater than 10 mg/L substantially increases the probability of relapse (HR: 1.5; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.1-1.9) within the next 92 days. The model was adjusted by fistulizing CD, presence of colitis, and level of stress60.

A second cohort study assessed the prognostic value of CRP in 71 patients with ileal, ileocolonic or colonic CD, using a cutoff value of 20 mg/L. According to this study, a positive result in the CRP test markedly increases the risk of relapse (RR: 10.5; 95% CI: 2.3-48.1) within the next 6 weeks61. Finally, a third study analyzed the role of CRP together with other serological tests as predictive markers in 53 patients with colonic CD. In said study, when the model was adjusted by calprotectin levels, gender, presence of smoking, extent of the disease, and azathioprine consumption, no significant differences in the risk of recurrence were found when CRP levels exceeded 9 mg/L (HR: 9.1; 95% CI: 0.5-53.3)62.

In addition, in a meta-analysis that was already described above24, a CPR sensitivity of 49% (95% CI: 0.34-0.64) and specificity of 92% (95% CI: 0.72-0.96) for the detection of endoscopic disease activity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease was found.

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR): a cohort study analyzed the predictive value of several biological tests in 101 patients with fistulizing, inflammatory or stenosing, intestinal or extraintestinal CD; in the bivariate analysis, no association between ESR values and subsequent risk of relapse was found (HR: 1.3; 95% CI: 1.0-1.7)60. On the other hand, another cohort study conducted in 71 participants determined the prognostic usefulness of ESR in patients with ileal, ileocolonic or colonic CD, reporting that when ESR exceeded 15 mm, the risk of relapse increased during the next 6 weeks (RR: 6.1; 95% CI: 1.9-18.9). Finally, according to the same study, high levels of CRP (>20 mg/L) and ESR (>15 mm) were significantly associated with recurrence of active Crohn’s disease within the next 6 weeks (RR: 9.9; 95% CI: 3.3-29.7)61.

Anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCA): only one cohort study, conducted in 101 patients with fistulizing, inflammatory or stenosing, intestinal or extraintestinal CD, determined the role of this biomarker as a predictor of relapse in CD patients. The analysis of this study failed to show an association between positivity for this marker and the subsequent development of active CD (HR: 1.2; 95% CI: 0.54-2.5)60.

Quality of evidence: very low ⊕ΟΟΟ

Fecal calprotectin

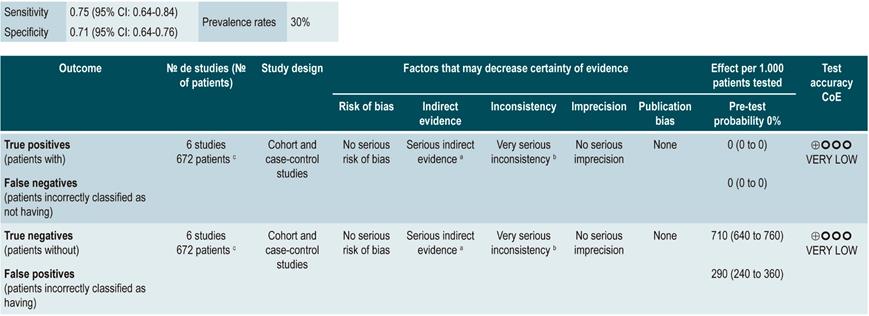

A systematic review and meta-analysis63 (AMSTAR score 8/11) evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of fecal calprotectin to predict relapse of CD. The presence of active Crohn’s disease, defined as having a CDAI score >150 or a Harvey-Bradshaw index score greater than 4 was determined as the standard of reference, and diagnostic accuracy was reported in terms of sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative likelihood ratios (LR+, LR-) and area under the curve values.

Based on the information provided by the six studies included in the systematic review, it was found that a positive value in fecal calprotectin levels (positivity range from 130 µg/g to 340 µg/g) acceptably predicts the development of recurrence of CD (sensitivity, 75%; 95% CI: 64%-84%; specificity, 71%; 95% CI: 64%-76%; LR+, 2.37; 95% CI: 1.56-3.61; LR-, 0.41; 95% CI: 0.27-0.61), with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.79 (95% CI: 0.74-0.64). Besides, the test performance was quite similar in the case of patients with colonic CD (sensitivity, 76%; 95% CI, 59%-88%; specificity, 77%; 95% CI, 69%-83%; LR+, 3.26; 95% CI, 1.89-5.25; LR-, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.19-0.60), with an AUC of 0.81 (95% CI, 0.76-0.86)63.

In the case of post-operative endoscopic recurrence of CD, sensitivity and specificity were 0.90 and 0.36, respectively, for a fecal calprotectin cutoff point of 50 μg/g; 0.81 and 0.57, for a cutoff point of 100 μg/g; 0.70 and 0.69, for a cutoff point of 150 μg/g; and 0.55 and 0.71, for a cutoff point of 200 μg/g. In patients with a small bowel CD diagnosis confirmed by capsule endoscopy, the sensitivity and specificity values were 0.83 and 0.53, for a cutoff point of 50 μg/g, and 0.42 and 0.94, for a cutoff point of 200 μg/g, respectively64.

The recently published CALM study combined the use of fecal calprotectin and CRP levels, reporting a mucosal healing rate in 79% of patients with calprotectin and CRP levels <250 μg/g and <5 mg/L, respectively65.

Quality of evidence: very low ⊕ΟΟΟ

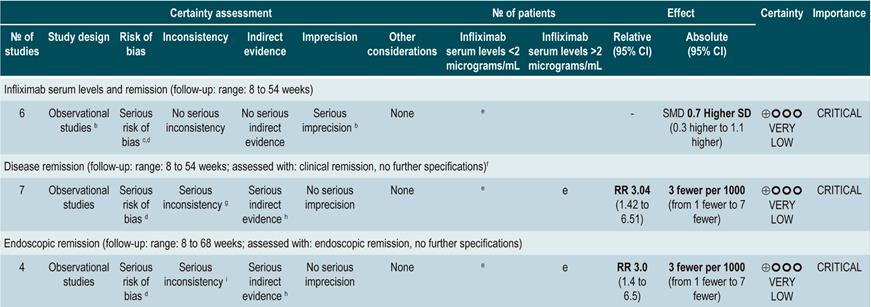

Serum levels of infliximab

A systematic review and meta-analysis66 (AMSTAR score 8/11) assessed the prognostic utility of serum levels of infliximab in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. The primary outcome was the frequency of clinical remission, while secondary outcomes included the proportion of patients with endoscopic remission and the need for colectomy. The review retrieved 22 observational studies, of which 11 were conducted exclusively in patients with CD, 4 in patients with ulcerative colitis, and 7 in individuals with indeterminate inflammatory bowel disease. Based on the findings of this systematic review, when infliximab levels exceeded 2 µg/mL at 14 weeks, patients with inflammatory bowel disease were more likely to achieve remission (RR: 2.91; 95% CI: 1.79-4.73) and intestinal mucosal healing (RR: 3.04; 95% CI: 1.42-6.51). Finally, the presence of undetectable serum levels of infliximab increased the probability of requiring colectomy compared to patients with detectable levels of this drug (RR: 5.4; 95% CI: 3.10-9.30)66.

Quality of evidence: very low ⊕ΟΟΟ

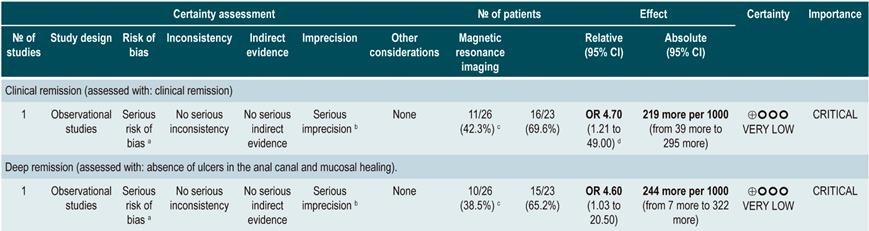

Using Magnetic resonance imaging to predict deep remission

A prospective cohort study67 assessed the usefulness of MRI in predicting deep remission in patients with perianal fistulizing CD. The outcomes of interest were the presence of remission and deep remission (which was determined using the Van Assche index, which evaluates the complexity, extension, and location of the fistula), contrast medium uptake, rectal mucosa involvement, and the presence of abscesses; the assessment was performed independently by two radiologists with expertise in gastrointestinal tract imaging studies and who were not informed on the clinical signs and symptoms of the patients.

The cohort consisted of 49 patients who were undergoing anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α therapy and concomitant use of immunosuppressants to induce or maintain remission of the disease. According to this study, factors associated with the presence of remission were absence of rectal involvement on the MRI (OR: 4.7; 95% CI: 1.21-49.0) and absence of switch of anti-TNF-α (OR: 7.7; 95% CI: not reported; p<0.05). Regarding deep remission, absence of rectal involvement on the MRI was strongly associated with absence of ulcers in the anal canal (OR: 4.6; 95% CI: 1.03-20.5)67.

A meta-analysis that included 12 studies on the performance of magnetic resonance enterography using a new technique based on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), which, unlike the conventional technique, is faster and does not require the intravenous administration of a contrast medium, reported a sensitivity of 92.9% (95% CI: 85.8%-96.6%) and a specificity of 91% (95% CI: 79.7%-96.3%) for detecting inflammation; however, there was heterogeneity among the studies retrieved, and authors concluded that there may be an overestimation of the results68. In addition, a recent systematic review considers this new technique a valid alternative to the conventional technique that is less invasive, faster, and does not require fasting or bowel preparation69.

Quality of evidence: very low ⊕ΟΟΟ

Use of capsule endoscopy to determine small bowel mucosal healing

In a systematic review and meta-analysis of 5 observational studies that included a total of 142 patients with CD who met the inclusion criteria, an association between a capsule endoscopy mucosal healing marker (Niv or Lewis score) and clinical remission at 12 weeks and 24 months of follow-up was found (odds ratio [OR]: 11.06; 95% CI: 3.74-32.73; p<0.001)70.

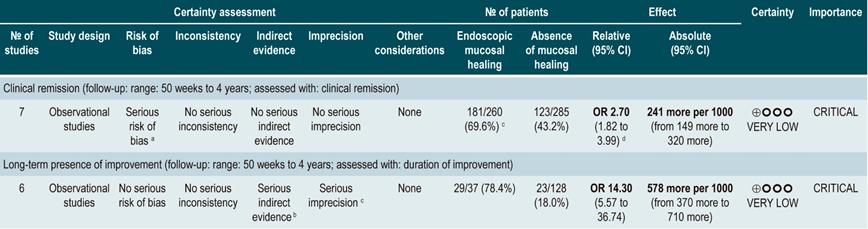

Mucosal healing

A systematic review38 (AMSTAR score 8/11) evaluated the prognostic value of intestinal mucosal healing in the occurrence of favorable clinical outcomes in CD patients. The following outcomes were considered: the frequency of long-term clinical remission (CDAI <150), the need for surgical treatment, and the rate of long-term mucosal healing.

The review retrieved 12 observational studies conducted in patients with stenosing or fistulizing, perianal, small bowel, ileocolonic, or colonic CD. According to this systematic review, the presence of healthy mucosa increases the likelihood of remaining in clinical remission for at least 50 weeks (OR: 2.7; 95% CI: 1.82-3.99; 304 patients), regardless of the type of treatment (biological therapy [OR: 2.89; 95% CI: 1.82-4.59] or non-biological therapy [OR: 2.48; 95% CI: 1.26-4.89]). Finally, the presence of healthy mucosa was also associated with a higher frequency of long-term endoscopic remission (OR: 14.3; 95% CI: 5.57-36.74), however it was not associated with a higher or lower frequency of patients requiring surgical intervention (OR: 0.22; 95% CI: 0.86-5.69)38.

Quality of evidence: very low ⊕ΟΟΟ

From evidence to the recommendation

The expert panel stated that CRP and ESR are low-cost tests and must be ordered simultaneously. The recommendation is strong because testing should be performed as part of a proper management of the disease that seeks to obtain the best outcomes for patients with CD.

The identification of serum levels of infliximab was not formulated as a recommendation due to its cost; only evidence about one biological drug was found, and this drug is not included in the health benefits plan of the mandatory health insurance coverage system in force in Colombia.

Question N° 2. What are the safest and most effective non-biological interventions to induce remission of crohn’s disease in patients older than 16 years?

List of recommendations

Summary of evidence

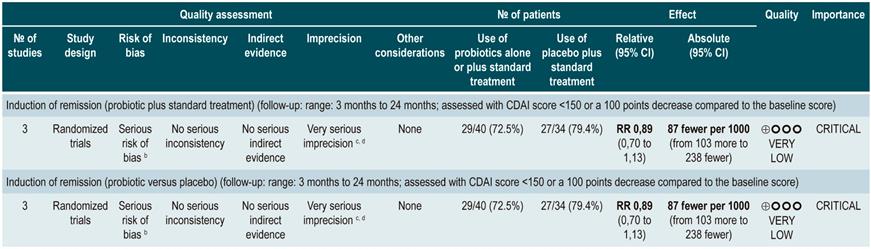

Using probiotics to induce remission in patients with active Crohn’s disease

A systematic review and meta-analysis71 (AMSTAR score 8/11) evaluated the efficacy of using probiotics to induce remission in patients with CD. In said study, the assessed outcome was the frequency of patients who achieved clinical remission (defined as having a CDAI <150 or obtaining a score less than 100 points compared to the baseline score) during 3 to 24 months of follow-up. The review retrieved three controlled clinical trials with a total of 74 participants; based on the findings reported, probiotic administration failed to increase the proportion of patients achieving remission, either when used as monotherapy (RR: 0.89; 95% CI: 0.70-1.13) or as an adjuvant in conventional treatment (RR: 0.89; 95% CI: 0.70-1.13)71. Furthermore, in a recent Cochrane review that included 2 studies on the use of probiotics to induce remission in CD, it was concluded that available evidence about the efficacy or safety of using probiotics to induce remission in CD is very uncertain when compared to placebo72.

Quality of evidence: very low ⊕ΟΟΟ

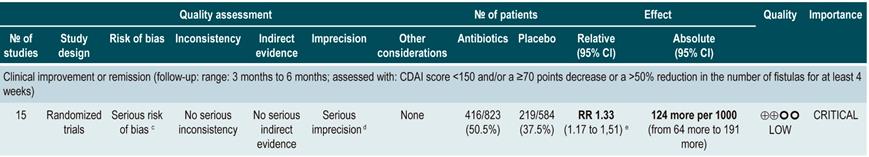

Using antibiotics to induce remission in patients with active Crohn’s disease

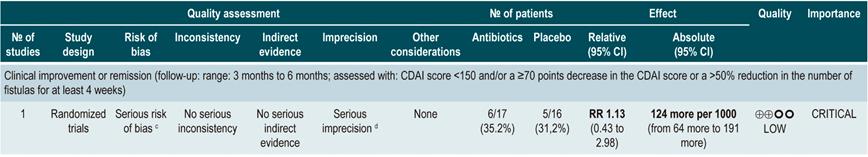

A systematic review73 (AMSTAR score 7/11) assessed the efficacy of using antibiotics to induce remission in patients with active CD. All studies included in the review allowed concomitant use of other interventions (immunomodulators) and the outcome of interest was the proportion of patients who achieved clinical improvement or remission (CDAI <150 and/or a ≥70 points decrease or a >50% reduction in the number of fistulas for at least 4 weeks) during follow-up.

The review retrieved three randomized clinical trials conducted in a total of 222 participants. When compared with placebo, the use of antibiotics during the first 3 to 6 months did not increase the proportion of participants experiencing clinical improvement or remission (RR: 1.15; 95% CI: 0.56-2.36). Also, when a subgroup analysis was performed according to the type of drug used, the administration of ciprofloxacin, rifaximin and 5-nitroimidazoles showed similar results73.

In addition, a recent Cochrane review of 13 studies suggests a modest benefit of using antibiotics in patients with active CD, and that their benefit for maintenance of remission is uncertain; therefore, according to this review, no solid conclusions regarding the efficacy of antibiotics in CD can be reached74.

Quality of evidence: low ⊕ΟΟΟ

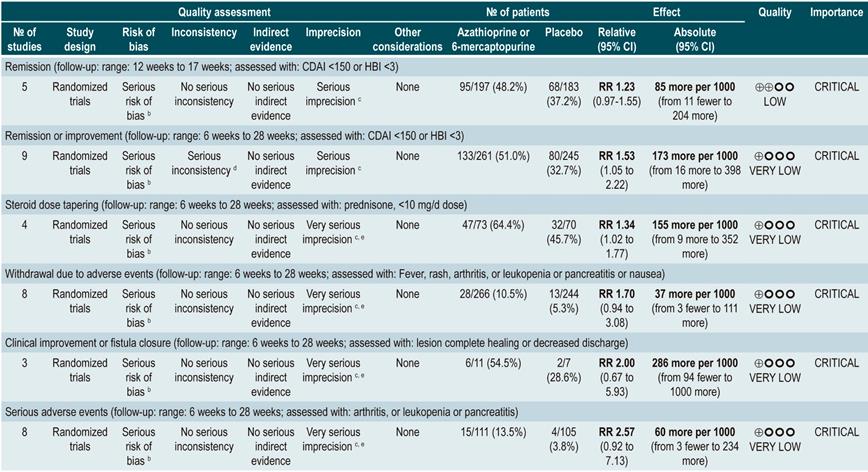

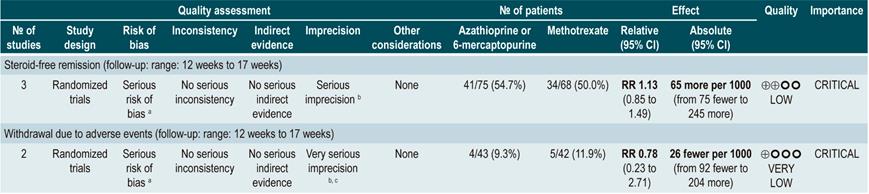

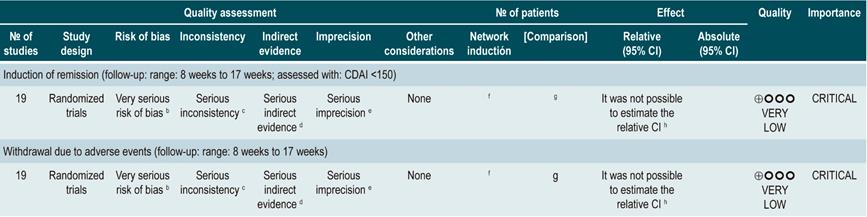

Using azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine to induce remission in patients with active CD

A systematic review and meta-analysis75 (AMSTAR score 10/11) evaluated the efficacy and safety of using azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine for induction of remission in CD. The outcomes assessed in this study were the proportion of patients who achieved remission or clinical improvement (defined as a CDAI <150 points or a HBI <3), the proportion of patients in which steroid dose reduction was possible (assessed with prednisone at doses <10 mg/d) and who experienced improvement or fistula closure (complete lesion healing or decreased discharge) and, finally, the proportion of patients who experienced serious adverse events, and the frequency of withdrawal.

The review retrieved nine studies evaluating the effect of this intervention compared to placebo in 506 participants in total. According to this systematic review, in patients who were administered azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine higher frequencies of clinical improvement (RR: 1.53; 95% CI: 1.05-2.22) and of lower steroid doses (RR: 1.34; 95% CI: 1.02-1.77) were observed, without this being reflected in a higher frequency of patients who achieved clinical remission criteria (RR: 1.23; 95% CI: 0.97-1.55) or who experienced clinical improvement or fistula closure (RR: 2.00; 95% CI: 0.67-5.93). However, the use of azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine did not increase the risk of withdrawal (RR: 1.70; 95% CI: 0.94-3.08) or the frequency of adverse events (RR: 2.57; 95% CI: 0.92-7.13)75.

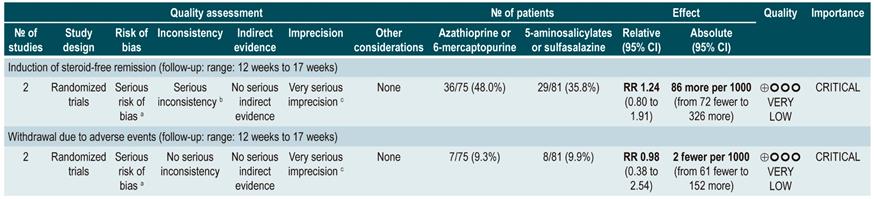

In a second analysis carried out in the same review, the efficacy and safety of azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine administration versus any other pharmacological intervention to induce remission in patients with CD were compared. When compared with methotrexate, the use of azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine did not increase the proportion of patients who had steroid-free remission (RR: 1.13; 95% CI: 0.85-1.49; 2 studies, 143 participants) or the frequency of withdrawal (RR: 0.78; 95% CI: 0.23-2.71; 2 studies, 85 participants). Likewise, when patients in the control group were administered 5-aminosalicylates or sulfasalazine, no statistically significant differences were found between groups (steroid-free remission [RR: 1.24; 95% CI: 0.80-1.91] and withdrawal [RR: 0.98; 95% CI: 0.38-2.54]; 2 studies, 156 patients)75.

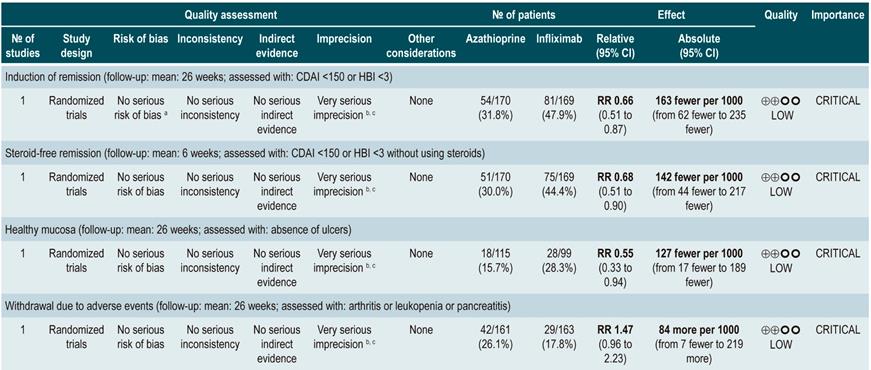

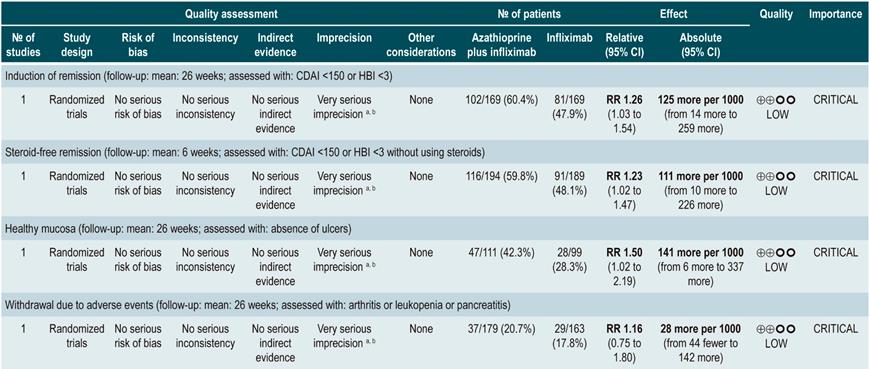

However, when azathioprine administration was compared with infliximab use (1 study, 339 participants), azathioprine was associated with a lower frequency of patients achieving clinical remission (RR: 0.66; 95% CI: 0.51-0.87), steroid-free remission (RR: 0.68; 95% CI: 0.51-0.90) or presenting healthy looking mucosa on endoscopic evaluation (RR: 0.55; 95% CI: 0.33-0.94); however, there were no significant differences regarding the frequency of adverse events between groups (RR: 1.47; 95% CI: 0.96-2.23). Finally, when combination therapy with azathioprine plus infliximab was compared with infliximab monotherapy, the use of combination therapy increased the proportion of patients who achieved clinical remission (RR: 1.26; 95% CI: 1.03-1.54), steroid-free remission (RR: 1.23; 95% CI: 1.02-1.47) or who had healthy-looking mucosa on endoscopic evaluation (RR: 1.50; 95% CI: 1.02-2.19), without increasing the frequency of adverse events (RR: 1.16; 95% CI: 0.75-1.80)75.

Quality of evidence: very low ⊕ΟΟΟ

Using 5-aminosalicylates to induce remission in patients with active Crohn’s disease

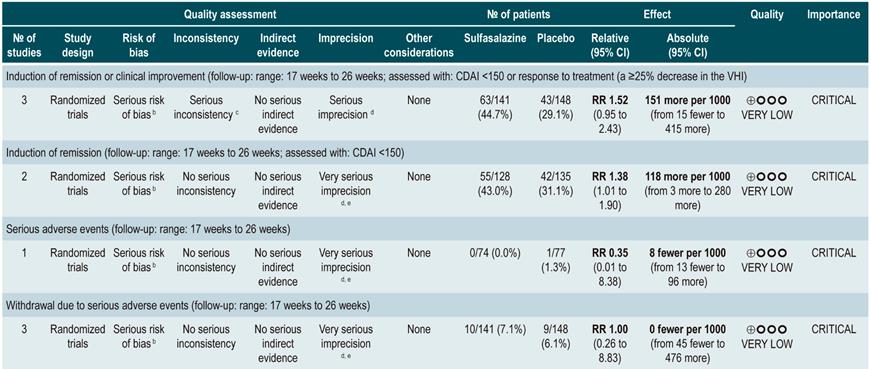

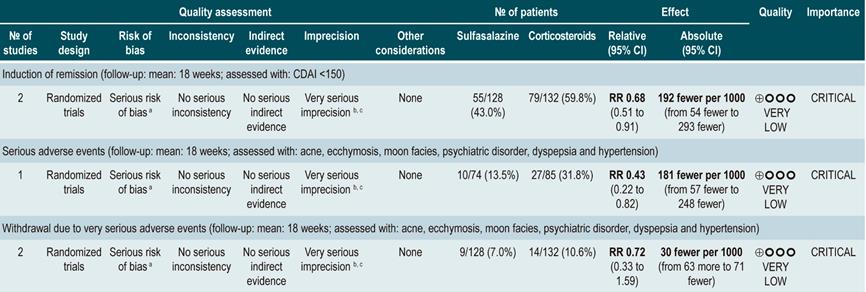

A systematic review76 (AMSTAR score 10/11) evaluated the safety and efficacy of using sulfasalazine to induce remission in patients with mild to moderate CD. This review reported findings on the following outcomes: the proportion of patients who achieved clinical improvement or remission (CDAI <150 or a >25% decrease in the VHI), the frequency of serious adverse events, and withdrawal due to undesirable effects.

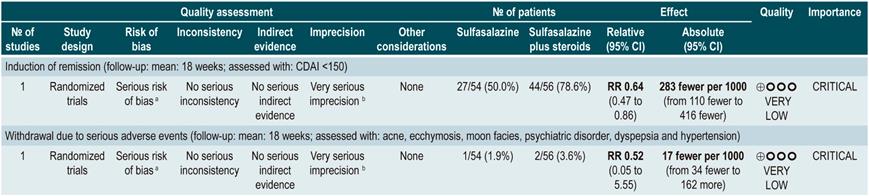

This review retrieved three controlled clinical trials comparing the use of this intervention versus placebo in 289 participants. Based on the results of the retrieved studies, it was found that sulfasalazine administration increased the frequency of remission (RR: 1.38; 95% CI: 1.01-1.90) but did not increase that of clinical improvement (RR: 1.52; 95% CI: 0.95-2.43), yet neither did it increase the incidence of serious adverse events (RR: 0.35; 95% CI: 0.01-8.38) or withdrawal (RR: 1.00; 95% CI: 0.26-8.83). In addition, in a second analysis, the efficacy and safety of sulfasalazine administration versus any other pharmacological intervention were compared. When compared with steroid therapy, the use of sulfasalazine was associated with a lower frequency of serious adverse events (RR: 0.43, 95% CI: 0.22-0.82; 2 studies, 159 participants) at the cost of a lower proportion of patients achieving remission (RR: 0.68, 95% CI: 0.51-0.91; 2 studies, 260 patients). No significant differences were found between groups regarding the rate of withdrawal (RR: 0.72; 95% CI: 0.33-1.59; 2 studies, 260 patients)76.

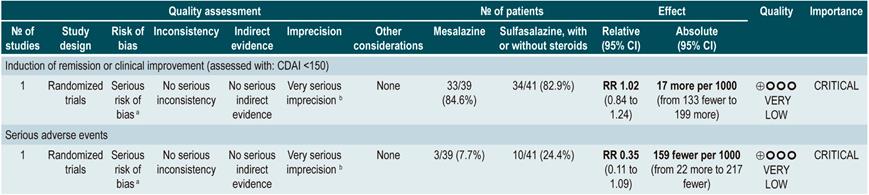

On the other hand, when 5-aminosalicylates monotherapy was compared with sulfasalazine-steroid combination therapy, sulfasalazine monotherapy was associated with a lower frequency of participants achieving clinical remission (RR: 0.64, 95% CI: 0.47-0.86; 1 study, 110 patients) and there was no statistically significant evidence regarding the rate of withdrawal (RR: 0.52, 95% CI: 0.05-5.55; 1 trial, 110 participants). Finally, a subgroup analysis based on the type of 5-aminosalicylates was performed in this review. When mesalazine was compared with sulfasalazine, no differences were found between groups in terms of efficacy (induction of remission [RR: 1.02; 95% CI: 0.84-1.24]) or safety ([serious adverse events: RR: 0.35; 95% CI: 0.11-1.09])76.

Quality of evidence: very low ⊕ΟΟΟ

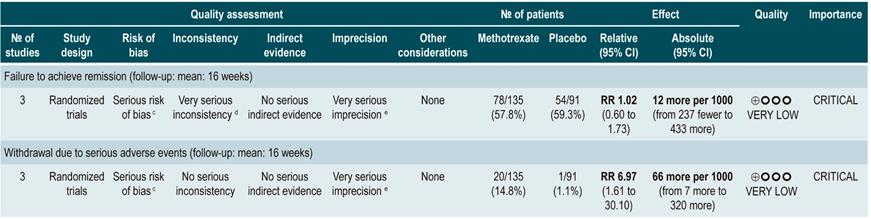

Using methotrexate to induce remission in patients with active Crohn’s disease

A systematic review77 (AMSTAR 8/11) assessing the safety and efficacy of using methotrexate for inducing remission in patients with CD was retrieved. The review included three studies conducted in a total of 226 participants. When compared to placebo, patients in the methotrexate arm did not experience a higher frequency of clinical remission (RR: 1.02; 95% CI: 0.60-1.73), but they did experience a higher frequency of withdrawal (RR: 6.97; 95% CI: 1.61-30.10)77.

Quality of evidence: very low ⊕ΟΟΟ

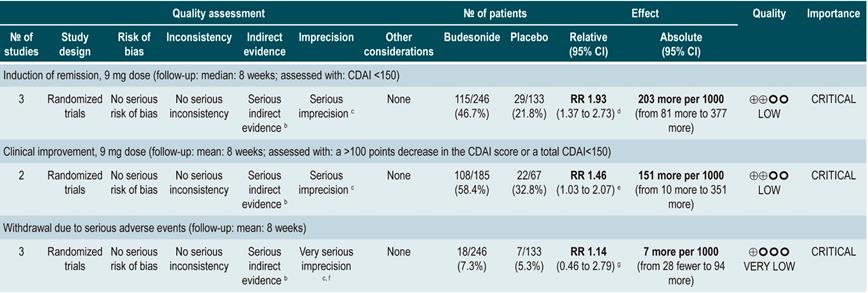

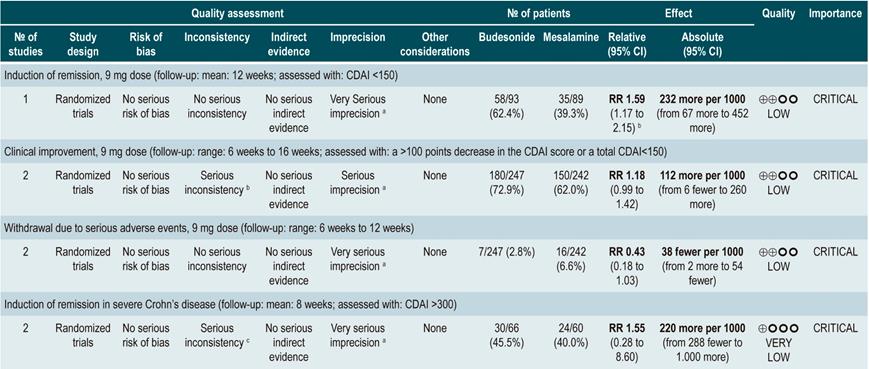

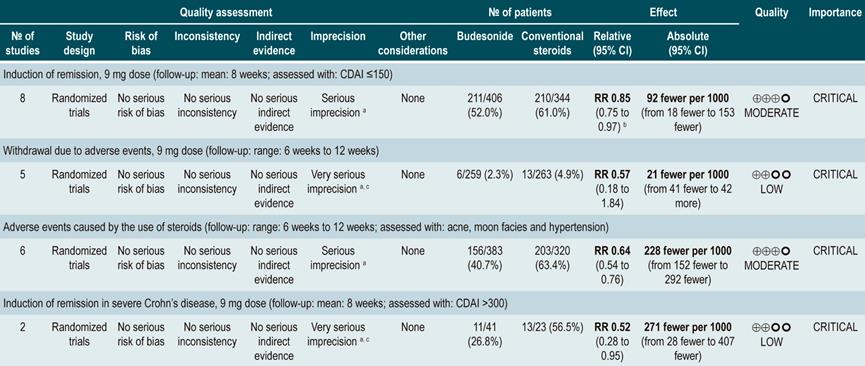

Using budesonide to induce remission in patients with active Crohn’s disease

A systematic review and meta-analysis78 (AMSTAR score 10/11) evaluated the efficacy and safety of using budesonide to induce remission in patients with CD. Outcomes assessed in this study were the proportion of patients achieving remission (defined as a CDAI <150 points) and clinical improvement (a >100 points decrease in CDAI score or total CDAI<150 points), and the proportion of patients withdrawing due to serious adverse events. A comparison of the effect of this intervention with that of place was performed in three studies (379 patients in total). According to the findings of this systematic review, in the budesonide administration group higher proportions of remission (RR: 1.93, 95% CI: 1.37-2.73, at 9 mg dose; RR: 2.25, 95% CI: 1.35-3.76, at 15 mg dose) and clinical improvement (RR: 1.46, 95% CI: 1.03-2.07, at 9 mg dose; RR: 2.34, 95% CI: 0.83-6.63, at 15 mg dose) were observed, without increasing the proportion of patients who withdrew due to adverse events (RR: 1.14, 95% CI: 0.46-2.79, at 9 mg dose; RR: 1.55, 95% CI: 0.45-5.34, at 15 mg dose).

Also, in a second analysis, this review compared the efficacy and safety of budesonide administration for induction of remission in CD versus any other pharmacological intervention. When compared with mesalazine administration, budesonide use at a dose of 9 mg increased the number of patients who achieved remission at 12 weeks (RR: 1.59, 95% CI: 1.17-2.15; 1 study, 182 participants) and 16 weeks (RR: 1.79; 95% CI: 1.28-2.50; 1 study, 182 participants), but it did not increase the frequency of clinical improvement (RR: 1.18; 95% CI: 0.99-1.42; 2 studies, 489 patients) or withdrawal (RR: 0.43; 95% CI: 0.18-1.03; 2 studies, 489 patients). On the other hand, when participants in the control group were administered traditional steroids, patients in the budesonide 9 mg arm experienced a lower frequency of remission in the medium term (RR: 0.85, 95% CI: 0.75-0.97; for 8 weeks), but not in the long term (RR: 1.02, 95% CI: 0.81-1.30; for 12 weeks). Finally, patients who were administered budesonide reported a lower frequency of adverse events (RR: 0.64; 95% CI: 0.54-0.76), yet this was not reflected in a higher or lower frequency of withdrawal (RR: 0.57; 95% CI: 0.18-1.84)78.

Quality of evidence: low ⊕⊕ΟΟΟ

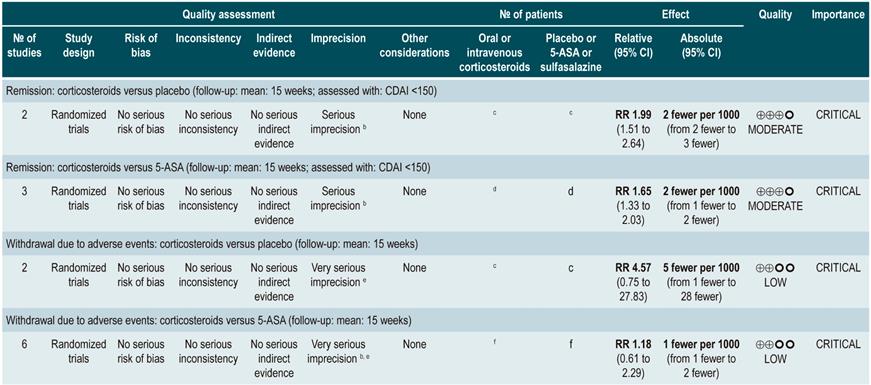

Oral or intravenous administration of corticosteroids to induce remission in patients with active CD

A systematic review79 (AMSTAR score 8/11) assessed the efficacy and safety of using corticosteroids (orally or intravenously) to induce remission in patients with CD. The outcomes reported in this study were the proportion of patients who achieved remission (defined as a CDAI <150 points) and the frequency of withdrawal due to serious adverse events. The effect of this intervention was compared with the effect of placebo in two studies (267 participants). According to the findings of the review, in the corticosteroid administration group, a higher frequency of remission was observed (RR: 1.99; 95% CI: 1.51-2.64), and the proportion of patients who withdrew did not increase (RR: 4.57; 95% CI: 0.75-27.83). On the other hand, a second analysis carried a comparison between the administration of steroids and 5-aminosalicylates use. Compared to the use of 5-aminosalicylates, corticosteroids were also associated with a higher frequency of remission (RR: 1.65, 95% CI: 1.33-2.03; 2 studies, 332 participants), without resulting in a higher frequency of withdrawal (RR: 1.18, 95% CI: 0.61-2.29; 6 trials, 478 patients)79.

Quality of evidence: low ⊕⊕ΟΟΟ

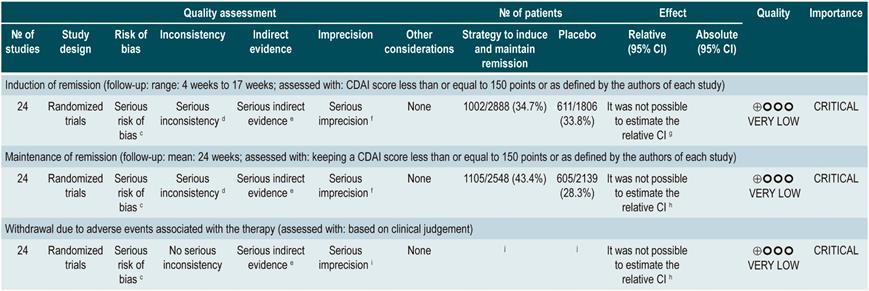

Safety and efficacy of using mesalazine, sulfasalazine, corticosteroids, and budesonide to induce remission in patients with active Crohn’s disease. Results of a network meta-analysis

A systematic review and network meta-analysis80 (AMSTAR score 8/11) evaluated the efficacy and safety of different pharmacological strategies for the induction of remission in CD. The review included studies conducted in patients with active Crohn’s disease (CDAI score between 150 and 400 points) located in the ileum, colon, cecum, or rectum. Studies that allowed the use of combination therapy or included individuals with postoperative recurrence of CD were excluded. The following interventions were assessed: administration of mesalazine, sulfasalazine, corticosteroids or budesonide, and the following outcomes were reported: induction of remission (CDAI score ≤150 points or as defined by the author) and withdrawal due to adverse events (assessed according to clinical judgment).

The review retrieved 24 randomized clinical trials. When compared with the placebo group, the administration of high doses of corticosteroids (OR: 3.86; 95% CI: 2.51-6.06), budesonide (OR: 3.18; 95% CI: 2.11-4.30; higher than 6 mg/d) or mesalazine (OR: 2.11; 95% CI: 1.39-3.31; higher than 2.4 g/d) had a significantly better performance than placebo in inducing remission. However, sulfasalazine therapy did not show a clear benefit when compared to placebo (OR: 1.56; 95% CI: 0.83-2.88). On the other hand, when determining which intervention could be the best therapeutic option, corticosteroids ranked first, followed by budesonide at doses >6 mg/d, mesalazine at doses >2.4 g/d and, finally, with a similar probability, low-dose budesonide, and sulfasalazine80.

Steroids and high-dose budesonide were significantly superior to mesalazine, sulfasalazine, or low-dose budesonide. Corticosteroids were superior to high-dose mesalazine (OR: 1.83; 95% CI: 1.16-2.88), but their efficacy was similar to that of high-dose budesonide therapy (OR: 1.21; 95% CI: 0.84-1.76). Finally, the frequency of withdrawal in all interventions was similar to that of placebo: low-dose mesalazine (OR: 1.74; 95% CI: 0.33-8.99) and high-dose mesalazine (OR: 1.07; 95% CI: 0.36-3.43), sulfasalazine (OR: 0.79; 95% CI: 0.01-14.36), low-dose budesonide (OR: 0.35; 95% CI: 0.03-2.45) and high-dose budesonide (OR: 0.94; 95% CI: 0.36-2.81) and, finally, corticosteroids (OR: 2.19; 95% CI: 0.59-8.70). Somehow, in the corticosteroids group the likelihood of withdrawal due to adverse events was 93% and 90% higher when compared with budesonide or high-dose mesalazine therapy, respectively80.

Quality of evidence: very low ⊕ΟΟΟ

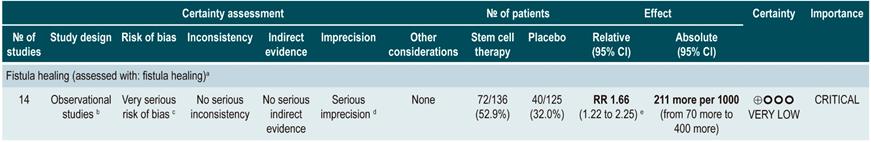

Stem cell therapy

A systematic review that included a meta-analysis of proportions81 (AMSTAR score 10/11) assessed the efficacy and safety of stem cell therapy in patients with active CD. The interventions considered in the review were the use of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells, adipose tissue or hematopoietic stem cells, and the outcomes reported were their clinical efficacy, defined as clinical response or remission, and the frequency of adverse events, endoscopic remission, and clinical recurrence. A total of 20 prospective experimental studies (563 patients combined) were retrieved. The overall frequencies of clinical response, endoscopic remission, and recurrence were 56% (95% CI: 33%-76%), 15% (95% CI: 0%-50%), and 16% (95% CI: 4%-34%), respectively. The overall frequency of adverse events was 12% (95% CI: 0.06-0.23).

In addition, when a subgroup analysis was performed according to the route of administration, the frequencies of clinical response and clinical remission in patients who underwent systemic therapy were 66% (95% CI: 39%-86%) and clinical 46% (95% CI: 25%-69%), respectively81.

Quality of evidence: very low ⊕ΟΟΟ

From evidence to the recommendation

The expert panel highlighted that this group of recommendations updates the guidelines of international agencies, and the importance this entails. In general, methotrexate, sulfasalazine and azathioprine are not recommended drugs to induce remission. The periods of time in which steroids should be used are reported as a good practice in order to use them adequately, thus minimizing side effects.

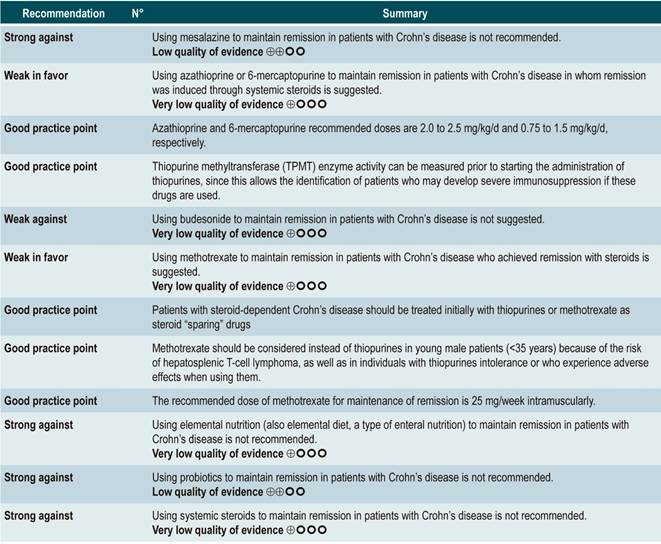

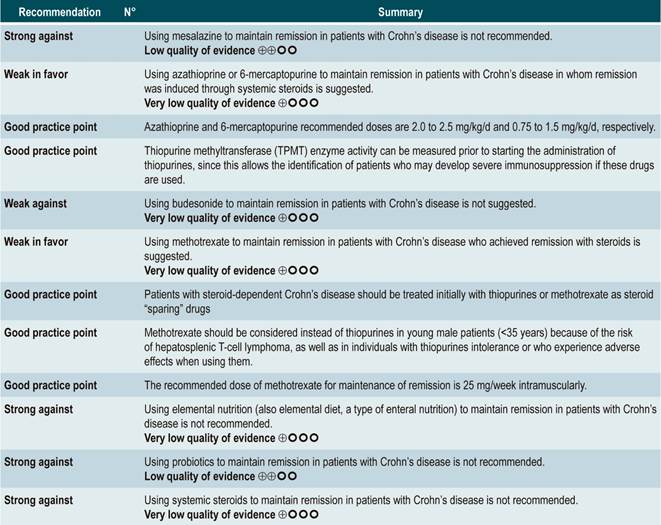

Question N° 3. What are the safest and most effective non-biological interventions to maintain remission of crohn’s disease in patients older than 16 years with?

Summary of evidence: General considerations

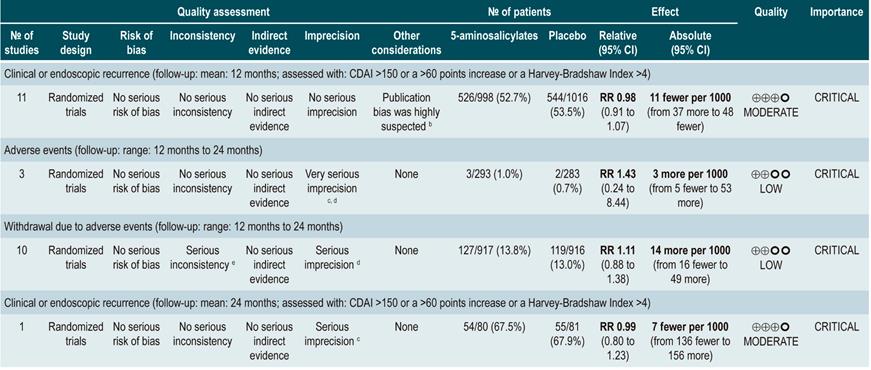

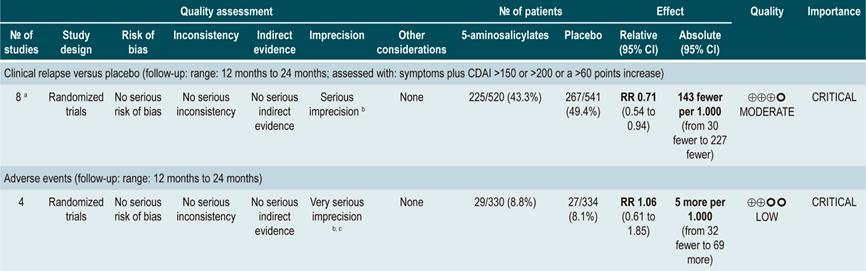

Using 5-aminosalicylates for maintenance of remission in Crohn’s disease

A systematic review82 (AMSTAR score 9/11) evaluated the safety and efficacy of using 5-aminosalicylates for maintenance of remission in CD. This review assessed the following outcomes: clinical or endoscopic recurrence at 12 or 24 months of follow-up (defined as having a CDAI >150 or a >60 points increase or a HBI >4) and the proportion of patients who experienced serious adverse events or who withdrew due to adverse events and serious adverse events.

The systematic review retrieved 11 randomized clinical trials conducted in a total of 2014 participants. When compared with placebo, the use of 5-aminosalicylates was not associated with lower clinical or endoscopic recurrence in the medium term (RR: 0.98, 95% CI: 0.91-1.07; 12 months) or the long term (RR: 0.99; 95% CI: 0.80-1.23; 24 months), nor with a higher frequency of serious adverse events (RR: 1.43; 95% CI: 0.24-8.44) or withdrawal due to adverse events (RR: 1.11; 95% CI: 0.88-1.38)82.

Quality of evidence: low ⊕⊕ΟΟ

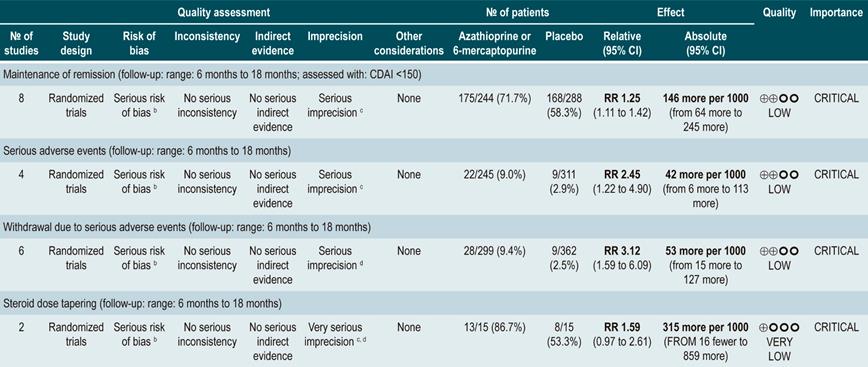

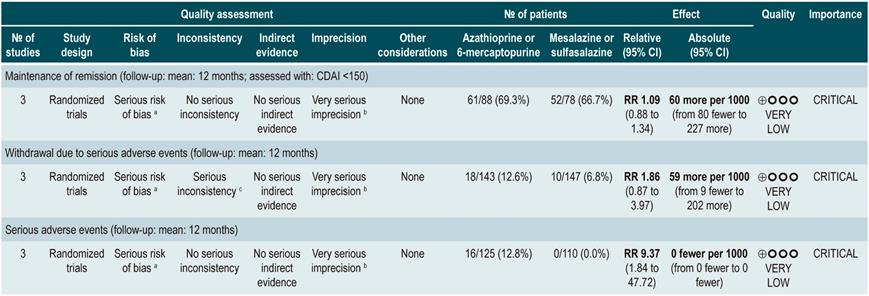

Using azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine to maintain remission in patients with Crohn’s disease

A systematic review83 (AMSTAR score 9/11) assessed the safety and efficacy of using azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine for maintenance of remission in CD. The following outcomes were reported: the proportion of patients who remained in remission (defines as having a CDAI <150), steroid sparing, and the frequency of serious adverse events or the frequency of withdrawals due to adverse events.

The review retrieved eight controlled clinical trials comparing this intervention versus placebo in 532 participants. Based on the evidence retrieved, the use of azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine increased the proportion of patients who were in remission at study enpoint (RR: 1.25; 95% CI: 1.11-1.42) at the expense of a higher frequency of serious adverse events (RR: 2.45; 95% CI: 1.22-4. 90) or withdrawal due to adverse events (RR: 3.12; 95% CI: 1.59-6.09), without modifying the proportion of patients in which reducing the steroid dose was feasible (RR: 1.59; 95% CI: 0.97-2.61)83.

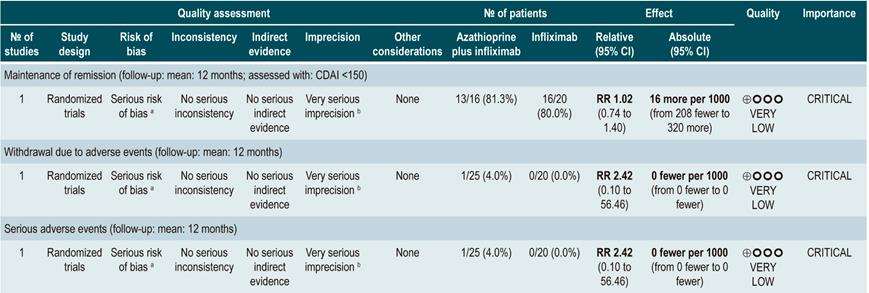

Furthermore, a second analysis was carried out to compare the administration of azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine with mesalazine or sulfasalazine therapy. When compared with 5-aminosalicylates therapy, azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine therapy was not associated with a higher or lower frequency of patients who remained in remission (RR: 1.09; 95% CI: 0.88-1.34) or who withdrew due to adverse events (RR: 1.86; 95% CI: 0.87-3.97), but it was associated with a higher incidence of serious adverse events (RR: 9.37; 95% CI: 1.84-47.72). Finally, in the last study retrieved in the review a comparison between combination therapy with azathioprine plus infliximab and monotherapy with infliximab was made. Combination therapy was not superior to infliximab in increasing the proportion of patients who remained in remission (RR: 1.02; 95% CI: 0.74-1.40). However, it did not increase the frequency of serious adverse events either (RR: 2.42; 95% CI: 0.10-56.46), nor of withdrawal (RR: 2.42; 95% CI: 0.10-56.46)83.

Quality of evidence: very low ⊕ΟΟΟ

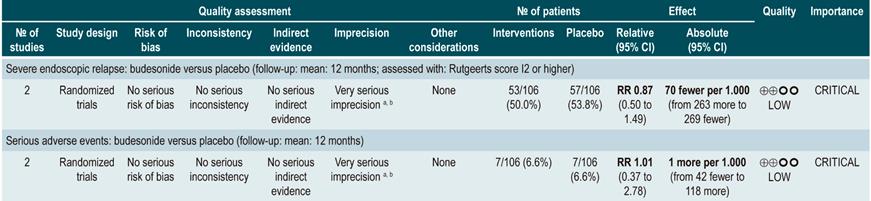

Using budesonide for maintenance of remission in Crohn’s disease

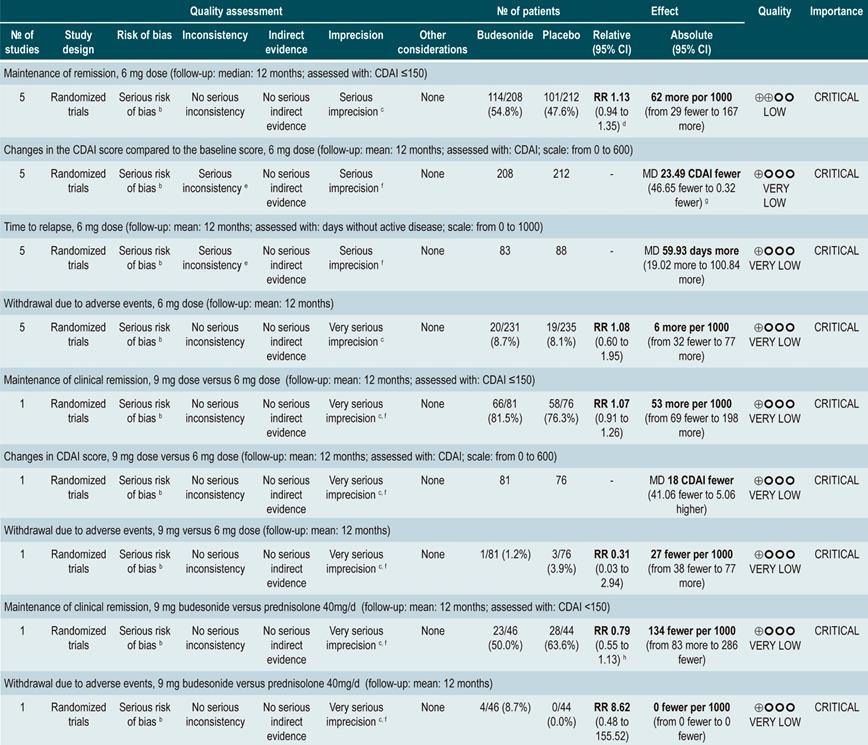

A systematic review84 (AMSTAR score 10/11) evaluated the safety and efficacy of budesonide administration for maintenance of remission in CD. With this in mind, the following outcomes were assessed: proportion of patients who remained in remission (defined as having a CDAI <150), mean change in CDAI score compared to the baseline score, mean time to the first relapse episode (measured in days), and the frequency of withdrawal due to an adverse event.

Five randomized clinical trials comparing the use of this intervention with the use of placebo in 420 patients combined were retrieved. Based on the evidence found, the use of budesonide at a dose of 6 mg/d did not increase the frequency of patients who remained in remission in the medium or the long term (RR: 1.15, 95% CI: 0.95-1.39; and RR: 1.13, 95% CI: 0.94-1.35; 6 and 12 months, respectively), although it did slightly decrease disease activity in the medium and the long term (MD CDAI score at 6 months: -24.30; 95% CI: -2.29 to -46.31; and CDAI score at 12 months: -23.49; 95% CI: -0.32 to -46.65) and slightly increased mean time to the first episode of relapse (MD: 59.93 days; 95% CI: 19.02-100.84 days), without significantly increasing the proportion of patients who withdrew due to adverse events (RR: 1.08; 95% CI: 0.60-1.95)84.

Also, when a subgroup analysis according to budesonide dose was performed, the increased dose of budesonide (9 mg versus 6 mg) did not increase the rate of remission (RR: 1.07; 95% CI: 0.91-1.26) or improve disease activity indices (MD CDAI score: -18; 95% CI: -41.06-5.06), but neither did it increase the frequency of withdrawal due to adverse events (RR: 0.31; 95% CI: 0.03-2.94). Finally, when budesonide therapy and the use of prednisolone 40 mg/d were compared, no significant differences were found between both groups regarding remission rate at 6 months (RR: 0.79; 95% CI: 0.56-1.12) or 12 months (RR: 0.79; 95% CI: 0.55-1.13) and the frequency of withdrawal due to adverse events (RR: 8.62; 95% CI: 0.48-155.52)84.

Quality of evidence: very low ⊕ΟΟΟ

Using methotrexate to maintain remission in patients with Crohn’s disease

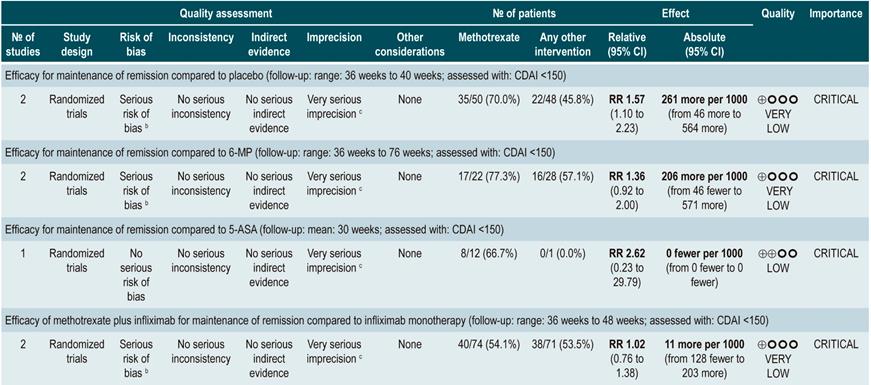

A systematic review and meta-analysis85 (AMSTAR score 8/11) evaluated the efficacy of methotrexate therapy for maintenance of remission in CD. The outcome assessed was the proportion of patients who remained in remission in a follow-up time ranging from 30 to 76 weeks (remission was defined as having a CDAI <150). Seven controlled clinical trials (306 participants in total) comparing methotrexate therapy with any other pharmacological intervention were retrieved. When placebo and methotrexate administration were compared, the latter increased the proportion of patients who remained in remission (RR: 1.57; 95% CI: 1.10-2.23); however, this finding was not consistent when methotrexate therapy was compared with 6-mercaptopurine (RR: 1.36; 95% CI: 0.92-2.00), 5-aminosalicylates (RR: 2.62; 95% CI: 0.23-29.79) or combination therapy with infliximab (RR: 1.02; 95% CI: 0.76-1.38)85.

Quality of evidence: very low ⊕ΟΟΟ

Using elemental nutrition (also elemental diet, a type o enteral nutrition) to maintain remission in patients with Crohn’s disease

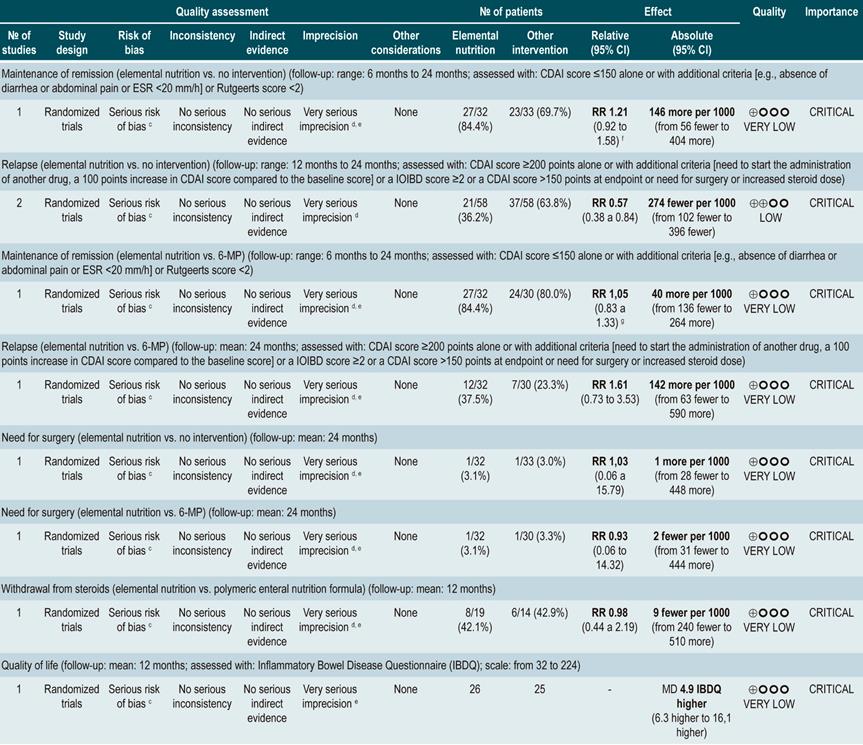

A systematic review86 (AMSTAR score 7/11) evaluated the efficacy of elemental nutrition for the maintenance of remission in CD by assessing the following outcomes: maintenance of remission (CDAI score ≤150 alone or Rutgeerts score <2), relapse (CDAI score ≥200 or a 100 points increase, or an IOIBD score ≥2, or increasing the steroid dose), need for surgical intervention, withdrawal from steroids, and health-related quality of life (assessed with the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire [IBDQ]).

Two controlled clinical trials conducted in a total of 116 participants were retrieved. When compared with the no intervention group (unrestricted diet), elemental nutrition did not significantly change the proportion of patients who remained in remission in the short (RR: 1.21; 95% CI: 0.92-1.58; at 6 months), medium (RR: 1.37; 95% CI: 0.86-2.17; at 12 months) or long term (RR: 2.06; 95% CI: 1.00-4.43; at 24 months) or the proportion of patients requiring surgical intervention (RR: 1.03; 95% CI: 0.06-15.79). However, it significantly reduced the risk the frequency of relapse episodes at 12 and 24 months of follow-up (pooled RR: 0.57; 95% CI: 0.38-0.84) and increased health-related quality of life scores during the first year of follow-up (MD IBDQ score=4.9; 95% CI: 6.3-16.1)86.

On the other hand, another study retrieved in this systematic review compared the efficacy of elemental nutrition versus 6-mercaptopurine therapy. No significant differences between both groups were found regarding maintenance of remission in the short (RR: 1.05; 95% CI: 0.83-1.33; at 6 months), medium (RR: 0.93; 95% CI: 0.64-1.35; at 12 months) or long term (RR: 0.77; 95% CI: 0.46-1.27), the frequency of relapse episodes (RR: 1.61; 95% CI: 0.73-3.53) or the need for surgical intervention (RR: 0.93; 95% CI: 0.06-14.32). Finally, there was also no difference in the frequency of patients who withdrew from taking steroids when elemental nutrition was compared with polymeric nutrition (RR: 0.98; 95% CI: 0.44-2.19)86.

A more recent Cochrane review comparing enteral nutrition with corticosteroids therapy in adult population reported a significant difference in favor of corticosteroids regarding remission rates in CD (45% vs. 73%) (RR: 0.65; 95% CI: 0.52-0.82); however, the quality of evidence was very low87.

Quality of evidence: very low ⊕ΟΟΟ

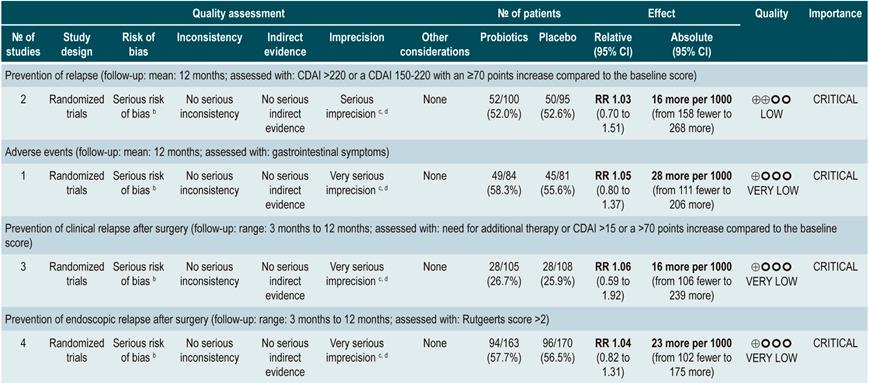

Using probiotics for maintenance of remission in Crohn’s disease

A systematic review88 (AMSTAR score 9/11) assessed the efficacy and safety of using probiotics for maintenance of remission in CD. The outcomes analyzed in the review were the frequency of relapse at 12-months (CDAI >220 or a CDAI 150-220 with an ≥70 points increase compared to the baseline score) and the incidence of adverse events resulting from the intervention. Four randomized clinical trials conducted in a total of 233 participants were included. Compared to placebo, the use of probiotics did not reduce the frequency of relapse episodes (RR: 1.03; 95% CI: 0.70-1.51), but neither did it increase the frequency of adverse events (RR: 1.05; 95% CI: 0.80-1.37)88.

Quality of evidence: low ⊕⊕ΟΟ

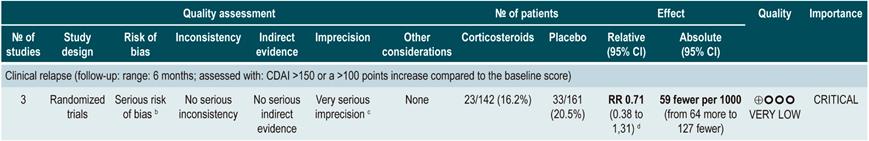

Using corticosteroids to maintain remission in patients with Crohn’s disease

A systematic review89 (AMSTAR score 8/11) evaluated the efficacy of corticosteroid therapy for the maintenance of remission in CD. Bearing this in mind, the review reported findings on the following outcome: frequency of relapse at 6, 12, and 24 months (a CDAI score >150 together by symptoms suggestive of CD). Three randomized clinical (303 participants combine) were included. Compared to the placebo group, corticosteroid therapy did not reduce the frequency of relapse episodes in the short (RR: 0.71; 95% CI: 0.38-1.31), medium (RR: 0.82; 95% CI: 0.47-1.44) or long term (RR: 0.72; 95% CI: 0.39-1.35)89.

Quality of evidence: very low ⊕ΟΟΟ

From evidence to the recommendation

Currently, thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) test is not available in Colombia; however, starting its use in the country would be an ideal scenario since patients treated with thiopurines may develop immunosuppression. The future inclusion of this test in the health benefits plan of the mandatory health insurance coverage system in force in Colombia is suggested.

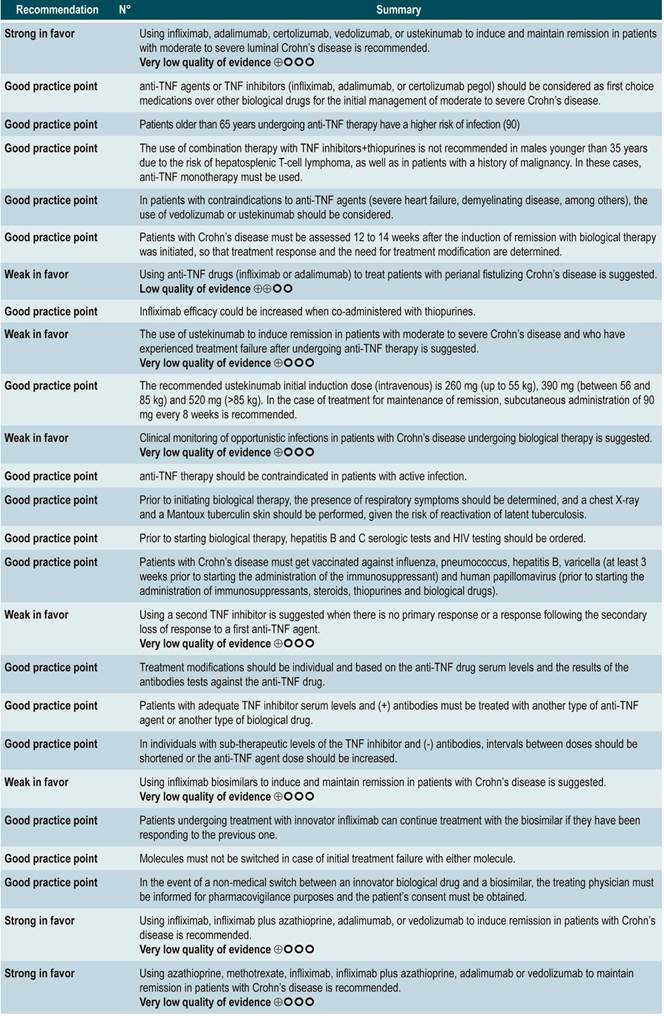

Question N°4. What is the safety and efficacy of using biological drugs to treat moderate to severe crohn’s disease in patients older than 16 years?

Summary of evidence: General considerations

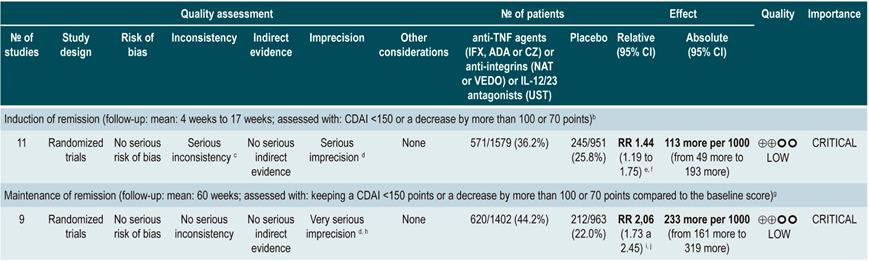

anti-TNF agents (infliximab, adalimumab or certolizumab pegol) or anti-integrins (natalizumab or vedolizumab) or IL-12/23 antagonists (ustekinumab) versus placebo for induction or maintenance of remission in moderate or severe luminal Crohn’s disease

A systematic review and network meta-analysis91 (AMSTAR score 9/11) assessed the efficacy, compared to placebo, of using anti-TNF agents (infliximab, adalimumab or certolizumab pegol) or anti-integrins (natalizumab or vedolizumab) or interleukin 12/23 (IL-12/23) antagonists (ustekinumab) for induction or maintenance of remission in patients with moderate or severe luminal colonic, ileal or ileocolonic CD. All studies included in the review allowed concomitant use of immunomodulators, corticosteroids and/or 5-aminosalicylates. The following outcomes were assessed: induction of clinical remission (a CDAI <150 or a decrease by more than 100 or 70 points) and maintenance of remission (a CDAI <150 or a decrease by more than 100 or 70 points compared to the baseline score).

The review retrieved 11 randomized clinical trials (2530 patients in total). Compared to placebo, a higher proportion of patients in the biologic drugs group achieved clinical remission (RR: 1.44; 95% CI: 1.19-1.75) and remained in remission (RR: 2.06; 95% CI: 1.73-2.45). When subgroup analysis was performed and the outcome of interest was the induction of remission, compared to placebo, the use of anti-TNF agents significantly increased the proportion of patients in which this outcome was achieved (OR: 1.63; 95% CI: 1.24-2.14), however anti-integrins (OR: 1.20; 95% CI: 0.97-1.49) or IL-12/23 antagonist ustekinumab (OR: 0.79; 95% CI: 0.44-1.39) were not significantly superior to placebo. In addition, in the network meta-analysis, infliximab (RR: 6.11; 95% CI: 2.49-18.29) and adalimumab (RR: 2.98; 95% CI: 1.12-8.18) were significantly superior to placebo in terms of induction of remission, while certolizumab pegol (RR: 1.48; 95% CI: 0.76-2.93), natalizumab (RR: 1.36; 95% CI: 0.69-2.86), vedolizumab (RR: 1.40; 95% CI: 0.63-3.28) or ustekinumab (RR: 0.61; 95% CI: 0.15-2.49) were not significantly superior to placebo. Infliximab had an 86% probability of being the most effective therapy, followed by adalimumab, with a 16% probability91.

On the other hand, according to the subgroup analysis in which the maintenance of remission was the outcome of interest, when anti-TNF therapy (OR: 2.18; 95% CI: 1.65-2.88) or IL-12/23 antagonist ustekinumab (OR: 2.09; 95% CI: 1.49-2.92) were used, a higher proportion of patients remained in remission. These findings were not observed when anti-integrins were used (OR: 1.52; 95% CI: 0.96-2.42). Besides, in the network meta-analysis, adalimumab (RR: 5.16; 95% CI: 1.78-18.00) and infliximab (RR: 3.31; 95% CI: 0.98-14.01) were superior to placebo in terms of maintenance of remission, while certolizumab pegol (RR: 2.26; 95% CI: 0.38-13.57), natalizumab (RR: 4.26; 95% CI: 0.71-25.49), vedolizumab (RR: 2.20; 95% CI: 0.37-13.54) and ustekinumab (RR: 0.91; 95% CI: 0.31-12.31) were not. Adalimumab had a 48% probability of being the most effective therapy, followed by natalizumab and infliximab, with a 29% and 11% probability, respectively91.

Quality of evidence: very low ⊕ΟΟΟ

A recent systematic review compared the efficacy and safety of biologic drugs (infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab, vedolizumab, and ustekinumab) as first-line (“biologic-naïve”) and second-line therapy (prior exposure to anti-TNF agents) in patients with moderate to severe CD. In total, 23 studies (randomized clinical trials; RCTs) were included: 8 using biologics as first-line agents, 6 using biologics as second-line agents, and 9 using them for maintenance of remission. Also, no head-to-head comparative studies were retrieved. In this review, the surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA), which represents the percentage of efficacy or safety achieved by an agent compared to an imaginary agent that is always the best choice and without uncertainty (i.e., SUCRA = 100%), for each biologic was determined. Infliximab (SUCRA, 0.93) and adalimumab (SUCRA, 0.75) had the highest SUCRA score for the induction of clinical remission in CD patients (moderate quality of evidence). On the other hand, in patients with prior exposure to anti-TNF agents (second-line therapy), adalimumab (SUCRA, 0.91) and ustekinumab (SUCRA, 0.71) achieved the highest rating for induction of remission (low quality of evidence). Adalimumab (SUCRA, 0.97) and infliximab (SUCRA, 0.68) had the highest scores for maintenance of remission, and Ustekinumab had the lowest risk of adverse events (SUCRA, 0.72) and infection (SUCRA, 0.71)92.

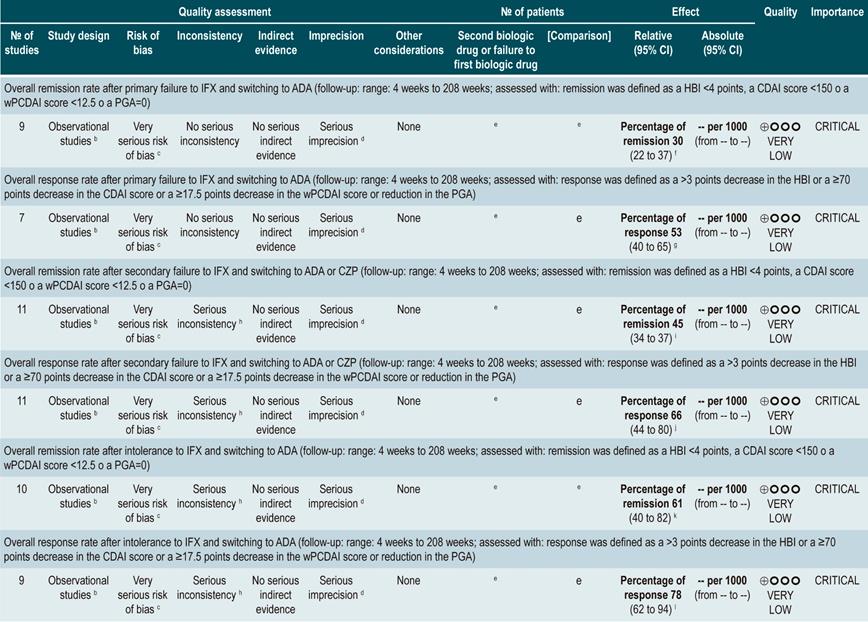

Efficacy of using a second anti-TNF agent in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and treatment failure or intolerance to a first biologic

A systematic review93 (AMSTAR score 8/11) evaluated the efficacy of using a second anti-TNF agent in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and primary or secondary failure or intolerance to a first anti-TNF agent therapy. Patients included in the studies retrieved were characterized by having luminal or fistulizing Crohn’s disease with CDAI score ranging from 220 to 450 points or a HBI ≥7 or by having “moderate to severe Crohn’s disease” or “steroid-dependent” disease or having experienced “failure to treatment with immunomodulators”. Out of all the studies identified, 32 evaluated switching from infliximab to adalimumab therapy: 4, from infliximab to certolizumab, and 1, from adalimumab to infliximab. The outcomes assessed were the overall rates of remission or response after primary failure and switching from infliximab to adalimumab, and from infliximab to adalimumab or certolizumab pegol, and, finally, the overall rate of remission or secondary response in case of intolerance to infliximab. According to this meta-analysis, the percentage of remission in the short, medium and long term was 18%, 30% and 28%, respectively; also, the short-, medium‐ and long‐term response rates after primary failure to infliximab and switching to adalimubab were, 35%, 67% and 42%, respectively93.

In the case of primary failure to infliximab and switching to adalimumab or certolizumab, the remission rates in the short, medium and long term were 41%, 38% and 60%, and the response rates in the medium and long term were 66% and 42%, respectively. Finally, remission rates in the short, medium and long term were 50%, 60% and 83%, respectively, and response rates in the medium and long term were 70% and 77%, when infliximab therapy was switched to adalimumab therapy due to intolerance. The frequency of adverse events was not reported in this meta-analysis93.

Quality of evidence: very low ⊕ΟΟΟ

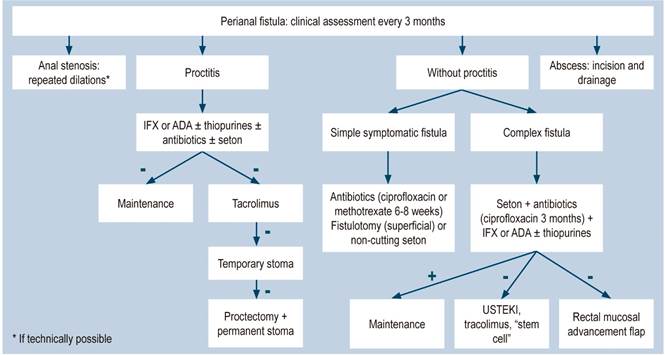

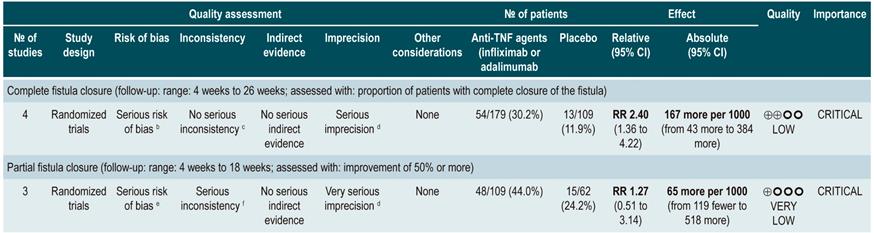

TNF inhibitors (infliximab or adalimumab) versus placebo in patients with fistulizing Crohn’s disease

A systematic review94 (AMSTAR score 8/11) evaluated the efficacy of using anti-TNF drugs (infliximab or adalimumab) to treat patients with CD and perianal or enterocutaneous or enteroenteral fistulas. Participants were administered infliximab 5 mg/kg or adalimumab 40 mg to 80 mg, and the outcomes assessed were complete or partial closure of the fistula. The review retrieved four randomized clinical trials conducted in 288 patients in total; when compared with patients in the placebo group, those in the anti-TNF therapy arm had a higher frequency of complete fistula closure (RR; 2.40, 95% CI: 1.36-4.22), but not of partial closure (RR: 1.27, 95% CI: 0.51-3.14)94.

Quality of evidence: very low ⊕ΟΟΟ

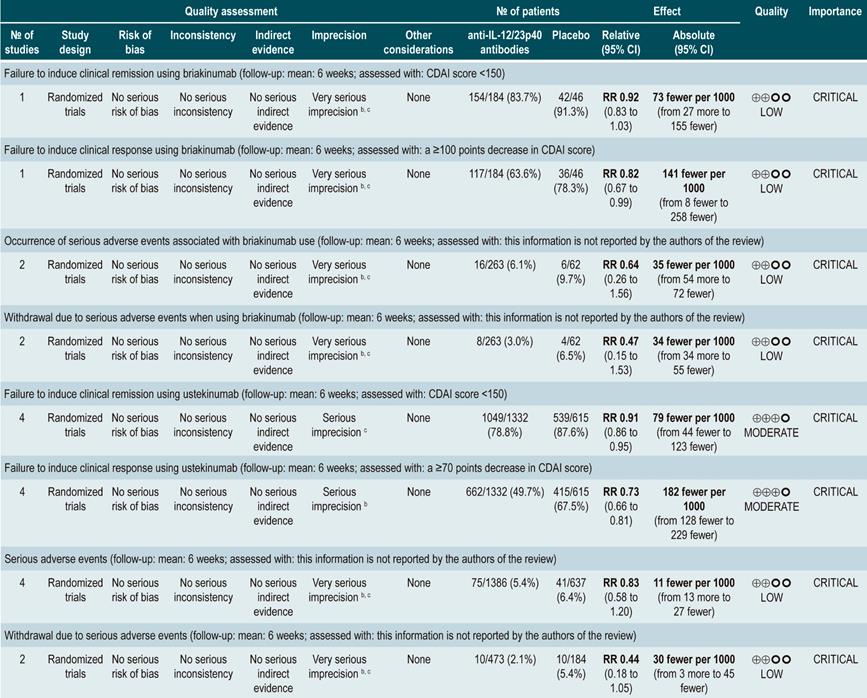

anti-IL-12/23p40 antibodies versus placebo for induction of remission in moderate to severe Crohn’s disease

A systematic review95 (AMSTAR score 9/11) evaluated the safety and efficacy, compared to placebo, of using anti-IL-12/23p40 antibodies for induction of remission in CD. Patients included in the ustekinumab or briakinumab therapy group had moderate to severe CD and prior failure to induce remission with anti-TNF agents or corticosteroids or immunosuppressants therapy. The following outcomes were assessed: failure to induce clinical remission (CDAI score <150) or clinical improvement (clinical response) (a ≥100 points decrease in CDAI score) and the frequency of serious adverse events or the frequency of withdrawal due to serious adverse events.

The review retrieved four randomized clinical trials (2023 participants in total). When compared with placebo, briakinumab was not associated with a lower frequency of failure to induce remission (RR: 0.92; 95% CI: 0.83-1.03). However, it was associated with a lower frequency of failure to induce clinical improvement (RR: 0.82; 95% CI: 0.67-0.99). There were no statistical differences between groups regarding the frequency of serious adverse events (RR: 0.64; 95% CI: 0.26-1.56) or of withdrawal due to adverse events (RR: 0.47; 95% CI: 0.15-1.53)95.

In addition, when compared with the placebo group, patients undergoing ustekinumab therapy had a lower frequency of failure to induce clinical remission (RR: 0.91; 95% CI: 0.86-0.95) or of failure to induce clinical improvement (RR: 0.73; 95% CI: 0.66-0.81). On the other hand, no significant differences were found between groups regarding the presence of serious adverse events (RR: 0.83; 95% CI: 0.58-1.20) or withdrawal due to adverse events (RR: 0.44; 95% CI: 0.18-1.05)95.

Quality of evidence: very low ⊕ΟΟΟ