Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) are the most common mesenchymal tumors of the gastrointestinal tract and account for 1 % to 2 % of all gastrointestinal tumors1. The incidence rate of GIST is estimated at 1 cases x 100 000 inhabitants per year. In the United States, the incidence varies from 5000 to 10 000 cases per year 2.

GISTs occur in any part of the gastrointestinal tract and are most frequently found in the stomach (60 %), followed by the small intestine (30 %), and between 5 % to 10 % in any part of the gastrointestinal tract (esophagus, colon, rectum, omentum, and mesentery)3. They originate in the interstitial cells of Cajal, pacemaker cells of the GI tract, and their mutation in the KIT gene seems to be the main responsible for the growth of these tumors. The diagnosis of GIST is based on knowledge of macroscopic and histological characteristics and immunohistochemical spectrum3.

Gastric lesions have a wide range of clinical behavior, varying from small lesions discovered by chance to large lesions with high aggressiveness and dissemination capacity. Symptoms are not specific and depend on size and location. Many lesions are small (less than 2 cm) and do not cause symptoms, but are discovered incidentally during endoscopic procedures, abdominal surgery, or radiological imaging. These lesions can also cause nonspecific discomfort such as dyspepsia and emesis, and may sometimes appear along with masses, severe abdominal pain, and even gastrointestinal bleeding.3

The objective of the present article is to describe the clinical presentation, diagnosis, management, recurrence, and survival of GISTs located in the stomach.

Materials and methods

Information was collected by reviewing the medical records of patients diagnosed with gastric GIST in a cancer center of Bogotá, Colombia, between January 2005 and December 2015. Demographic, clinical, histological, and immunohistochemical characteristics reported in biopsy were recorded, as well as the surgical specimen of each of the detected cases. Treatments included open surgery, laparoscopic management, and perioperative chemotherapy in some cases. Data about the procedure included the type of management and surgical approach, location, size, mitotic index, and risk classification. Risk categorization was based on the consensus of the National Institute of Health (NIH) and the U.S. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology regarding the size of the lesion and its mitotic index4.

Management with imatinib was used in several scenarios, including adjuvant therapy after standard surgical resection of resectable lesions classified as high risk, and with neoadjuvant intent for 3 to 6 months for locally advanced or borderline resectable lesions. Unresectable, metastatic, or recurrent lesions were also treated with imatinib. Follow-up was carried out until performing the last clinical and imaging follow-up, during which disease-free survival, overall survival, recurrence, and management were established.

Statistical analysis

This is a retrospective observational study based on a case series. Categorical variables were summarized as percentages. In the case of continuous variables, medians and the corresponding interquartile range (IQR) were used as summary measures. Death and recurrence were considered as outcomes; incidence density rates were estimated for their description, taking into account the differential follow-up time. These rates were expressed using 100 patients per month as the denominator and were calculated by taking follow-up losses or no outcome as right censoring; the rates were calculated along with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). In addition, survival functions were calculated and plotted using the Kaplan-Meier method. Statistical analyzes were carried out using the Stata 12 ® software.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

From January 2005 to December 2015, 31 patients with a diagnosis of gastric GIST were found. The median age was 61 years (IQR: 12). Of the 31 patients, 18 were female and 13 were male. Regarding clinical presentation, abdominal pain was the most reported symptom (Table 1).

Table 1 Demographic and clinical characteristics of the case studies

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | ||

| - Male | 18 | 58,1 |

| - Female | 13 | 41,9 |

| - Total | 31 | |

| Symptoms | ||

| - Pain | 15 | 48,4 |

| -Bleeding | 763 | 22,6 |

| - Mass | 31 | 19,4 |

| - Asymptomatic | 15 | |

| - Total | 763 | |

| Localization | ||

| - Body | 20 | 64,5 |

| - Antrum | 65 | 19,4 |

| - Fundus | 31 | 16,1 |

| - Total | 20 | |

| Risk | ||

| - High | 11 | 35,5 |

| - Intermediate | 4 | 12,9 |

| - Low | 16 | 51,6 |

| - Total | 31 | |

| Surgey | ||

| - Open | 21 | 67,7 |

| - Laparoscopy | 6 | 19,4 |

| - None | 4 | 12,9 |

| - Total | 31 | |

| Histological type | ||

| - Fusocellular | 16 | 51,6 |

| - Epithelioid | 2 | 6,5 |

| - Mixed | 5 | 16,1 |

| - Not reported | 8 | 25,8 |

| - Total | 31 | 16,1 |

| Immunohistochemistry | ||

| - CD117 | 28,0 | 90,32 |

| - CD34 | 27,0 | 87,1 |

| - Total | 31 | |

| Mutation in exon 11 | ||

| - Mutated | 2 | 6,5 |

| - Not mutated | 29 | 93,5 |

| - Total | 31 |

CD: cluster of differentiation.

According to the location in the stomach, the most frequent site was the body (Table 1).

3 asymptomatic cases were diagnosed incidentally during upper GI tract endoscopy and tomography.

Concerning tumor size, the largest lesion was 26 x 20 cm, and the smallest lesion was 2 x 2 cm. When size was correlated with the mitotic index to stratify risk, 11 patients (35.5 %) were at high risk, 16 patients (51.6 %) at low risk, and 4 at intermediate risk (12.9 %).

Histological and immunohistochemical characteristics

With regard to histological distribution, the fusocellular type was the most frequent and was found in 16 patients, followed by epithelioid in 2 patients, mixed in 5 patients, and without report in 8 patients. CD117 was positive in 90.32 % of cases (n = 28) and CD34 in 87.1 % (n = 27). Ki-67 was reported in 71 % of patients (n = 22) with a median of 4.5 (IQR = 3). The mitotic index had a median of 3 x 50 HPFs (IQR = 3). 5 patients had metastases (16.1 %) that were located in the liver (in the 5 cases) and 2 in the peritoneum.

In relation to the molecular study or mutational study, it was done in 2 patients in whom the exon 11 mutation was detected.

Surgical treatment

The most frequently surgical treatment performed was open surgery in 21 cases (67.74 %), followed by laparoscopy in 6 (19.35 %), and no procedure in 4 patients due to the size of the lesion (2 cases), elderly age (1 patients), or metastatic disease (1 patient) (Table 1).

Medical management

Of the 31 patients, 16 received imatinib (IMB), in 8 cases after surgical resection (adjuvant) due to high-risk lesions, in 2 cases because of metastatic lesions, and in the other 3 with neoadjuvant intent; the remaining 3 received it due to disease recurrence. Treatment was provided for a median of 0 months (IQR = 24). Of the patients with adjuvant therapy, 3 received treatment for 3 years, 3 for 1 years, and 2 for 2 years.

Follow-up

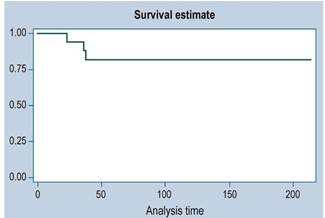

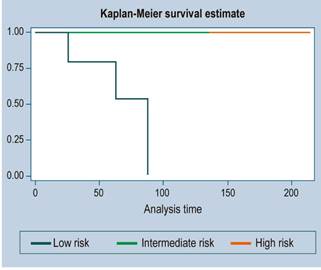

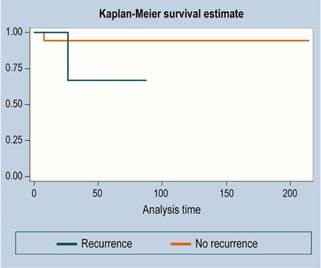

There were 3 cases of recurrence. The median follow-up time was 36 months. The survival function is illustrated in Figures 1, 2 and 3 (more than 50 % of cases had no mortality outcome, so median survival was not estimated).

There were 2 cases of death and a total of 1480 months of follow-up. This follow-up time ranged from a minimum of 2.4 months to a maximum of 214.7 months. The median follow-up time was 41.4 months. The mortality rate was 0.14 deaths per 100 patients/month (95% CI: 0.03 a 0.34

Of the 11 high-risk patients, 6 were alive at 5 years, but with disease; in other words, despite being treated as high-risk patients, more than 45% were alive and without disease at 3 years.

Discussion

The true incidence of GIST has not been well established. In the United States, however, the estimated annual incidence is 3000 to 6000 cases per year. They can occur at any age, most patients are between 40 and 80 years of age, and are slightly more common in men. These lesions can originate in any part of the gastrointestinal tract, and the stomach is the most involved site5.

In most series, gastric tumors are between 45 % and 60 %6. Folgado et al. found that 20 (46.5 %) of 43 patients studied over a 10-year period had tumors in the stomach (7). In a series of 31 patients, Vargas et al. found 14, which is equivalent to 45 % of the cases8. In a review conducted by the Instituto Nacional de Cancerología (National Institute of Cancerology) of Bogotá, from 2000 to 2008, 39 patients were reported, of which 16 had gastric tumors (41 %)9. For Flores-Funes in Spain, in a review performed between 2002 and 2015 with 66 patients, 43 cases (65 %) were located in the stomach10.

Clinical manifestations vary widely. 70 % of patients present with symptoms, 20 % are asymptomatic and, and another 10 % are found in autopsy studies5. For some series, the most frequent manifestation was gastrointestinal bleeding (45 %), followed by abdominal pain (30 %)11. In this series, 80 % of patients had symptoms, and abdominal pain was the most frequent in 18 patients, followed by gastrointestinal bleeding in 7. Three patients were asymptomatic (9.7 %) with 2 cm lesions in 2 patients and the third with a 4 cm lesion.

Symptoms are highly dependent on size. Tumors larger than 6 cm are usually symptomatic, while lesions smaller than 2 cm are indolent. With respect to size, the largest lesion was 26 x 20 cm, and the smallest lesion was 2 cm. Lesions larger than 5 cm were found in 17 patients and, when size was correlated to the mitotic index to stratify the risk, 11 patients (35.5 %) were at high risk, 16 patients (51.6 %) at low risk, and 4 patients at intermediate risk (12.9 %).

Regarding location, the fundus appears to be the predominant site with 25 %, followed by the body, and the antrum in 10 %.10

In this series, the body was the site of the highest number of lesions (20 cases), followed by the antrum and fundus.

The natural history of gastric GISTs is variable and has not been completely elucidated. One of the most important features is their variable and unpredictable biological behavior. They are not defined as malignant or benign, but their risk stratification for malignancy is based on the size of the lesion and the mitotic index or count12.

Small lesions tend to have a benign biological behavior, while larger lesions are more aggressive; however, it appears that any gastric lesion has the potential to be malignant. For this reason, surgical resection is the recommendation once they are diagnosed. Several studies have been conducted to measure the natural course of unresected lesions. These studies limit the size of subepithelial lesions to 2-3 cm and emphasize changes in size and ultrastructure determined by the endosonographic assessment over a follow-up period12. Gastric lesions have a more favorable prognosis compared to lesions in other locations13.

These lesions are very friable and hypervascular, so they are visualized as heterogeneous lesions on tomography. The diagnosis is usually confirmed by pathological examination. Morphology is fusiform in 70 %, epithelioid in 20 %, and mixed in 10 %14, which is similar to the findings reported in this series.

GIST proliferation is the result of mutation in the KIT proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase in 80 %, or in the platelet-derived growth factor in 10 %. The other 10 % corresponds to mutations of the BRAF gene14.

They all express CD117 and C-KIT positivity is the most specific immunohistochemical marker. Approximately 5% of these tumors may be C-KIT negative, CD34 + 60% to 70%, SM + 30% to 40%, and S100 + 5%. DOG1 may be useful in cases of C-KIT-negative GIST. Approximately 70 % of C-KIT mutations are located in exon 11, 10 % to 15 % in exon 9, and less frequently in exons 13 and 17. Mutations in platelet-derived growth factor receptor A (PDGFRA) are usually found in exon 1813. Most gastric GIST mutations are in exon 11. Only 2 of our patients underwent a mutational study, finding a mutation in exon 11.

The endoscopic appearance is of a subepithelial lesion with or without ulceration. Endoscopy may also show extrinsic compression with minimal mucosal involvement. These tumors may have large sizes with significant growth and increased demand for vascular supply, leading to central ulceration of the lesion12.

Several studies have reported the existence of lesions known as micro-GIST, which are lesions less than 1 cm discovered in pathology studies due to cancer gastrectomies (35 %) or in autopsy studies of patients older than 50 years (22.5 %). With upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, the diagnosis of a greater number of subepithelial lesions or tumors has increased. Several studies have shown that they are more common than previously assumed. For this reason, it is very important for an endoscopist to be familiar with the management of this pathology15.

Gastric lesions occur as micro-GIST (lesions less than 1 cm), mini-GIST (1 to 2 cm), and clinically relevant GIST (symptomatic or greater than 2 cm). The first 2 are indolent and do not progress clinically significantly. Most micro-GIST appear to be less active from a mitotic point of view and have different mutations compared to clinically relevant GIST. In an analysis comparing 101 GIST < 2 cm with 170 lesions > 2 cm, most tumors less than 1 cm had no mitotic activity14.

Most subepithelial lesions are identified incidentally by endoscopy due to indications for other causes, screening, medical check-ups, endoscopic controls for another cause, among others. These lesions include GIST, leiomyomas, lipomas, schwannomas, ectopic pancreas, or cystic duplication, and cannot be diagnosed until histologic examination is performed; however, obtaining a sample of these lesions by conventional endoscopic biopsy is difficult. For this reason, fine needle aspiration with endosonography is the best way to obtain tissue samples for pathological diagnosis14.

It is well known that some gastric lesions are observed in clinical practice as subepithelial tumors. Almost half of these lesions are GISTs after surgical resection14.

Endosonography-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy has recently shown histological confirmation of these lesions and suggests a management strategy. However, it is difficult to obtain adequate tissue samples from small and difficult to localize tumors. Endoscopic and endosonographic parameters that include a 25 % increase in lesion size, irregular external margins, cystic spaces, and altered echogenicity are indicative of malignant changes15.

This type of gastric lesions can be classified into several types15:

Type I: lesion with a very small relationship with muscularis propria, protruding into gastric lumen, similar to a polyp;

Type II: lesion with a wide contact with muscularis propria and also protruding into the gastric lumen;

Type III: lesion located in the middle part of the gastric wall, within the muscularis propria;

Type IV: lesion that protrudes into the serosa of the stomach with greater extragastric involvement.

Lesions smaller than 2 cm can be followed with endosonographic control safely and annually. They should also be resected if changes in size and endosonographic characteristics are determined. For larger lesions, histologic diagnosis is necessary due to differential diagnoses. If endosonography-guided fine-needle aspiration is not possible, primary surgical resection should be the best alternative15.

Surgical resection is the cornerstone of therapy for a localized lesion. The aim is to achieve complete resection of the lesion with negative margins15. It is critical not to rupture the pseudocapsule of the tumor because of the risk of disease dissemination, which results in a poor prognosis15.

Depending on the location of the lesion and its size, the type of surgical treatment is indicated. Wide or wedge resections are preferred for most lesions, but sometimes partial, subtotal, or total gastrectomies should be considered. Laparoscopic resection surgery, which is less invasive than traditional surgery, has shown similar results in terms of efficacy, safety, and hospital stay16. Some guidelines suggest that laparoscopic management is preferred for lesions less than 5 cm. However, laparoscopic approaches have expanded their indications for larger lesions, but what matters is expertise in oncological management, which prevents rupture during resection and ensures adequate lesion-free margins17.

Surgical management then depends on size, location, and experience of the operator. Endoscopic resections, open or laparoscopic surgical resections, resection with combined laparoscopy and endoscopic-assisted procedures (cooperative surgery), and transgastric surgery may be performed.15,18)

In a systematic review and meta-analysis comparing laparoscopic surgery with open surgery to treat gastric GIST, 189 studies found that there was no difference between surgical time, adverse events, intraoperative blood loss, overall survival, and recurrence rates. This study concluded that laparoscopic surgery is safe and effective for the management of gastric GIST and is associated with a shorter hospital stay19.

For very large lesions near the esophagogastric junction or pylorus, the best alternative is total or subtotal gastrectomy, avoiding deformities and poor gastric emptying. The size of the lesion, its location, and growth pattern determine both the need for intraoperative endoscopy and the type of resection. In type IV lesions, identification by laparoscopy alone is sufficient and usually wedge or exogastric resection with linear mechanical stapler offers a rapid alternative with an adequate resection margin19-21. In contrast, type I lesions located in the anterior wall may require endoscopic identification and, depending on their size, transgastric resection including the serous surface, where its implantation base is found with subsequent closure of the gastric defect22. Tumors located in the posterior wall can also be resected through a gastrotomy in the anterior wall by performing mechanical suturing from inside the stomach with the closure of the subsequent gastrotomy; otherwise, healthy gastric tissue can be sacrificed, which can lead to deformities that eventually result in inadequate gastric transit. Lesions of the fundus or those located in the greater curvature can be resected using the exogastric technique. The intragastric technique using transgastric transabdominal trocars is designed for subcardial lesions smaller than 4 cm, except for those located in the anterior wall due to the technical difficulty caused by the subsequent removal of the lesion in a perorally11,18-20,22,23.

Another treatment alternative for these subepithelial lesions is endoscopic resection with submucosal tunneling. This technique has advantages over submucosal dissection in terms of maintaining the integrity of the mucosa and submucosa, which promotes or facilitates wound healing and reduces the risk of pleural and abdominal infection. This technique should be performed by experienced endoscopists and is indicated for lesions smaller than 3 cm and preferably not deep in the muscular wall due to the risk of injuring the serosa24.

The limitations of this work include its retrospective nature and the small number of cases, but considering the incidence of this disorder, the sample size may be representative and significant.

Conclusions

Of 31 patients diagnosed with gastric GIST over a 10-year period, most (67 %) were treated with open surgery; however, laparoscopy was safely used as an alternative, thus providing the benefits of minimally invasive surgery with oncologic safety. The most frequent location in the stomach was the body, with 20 cases. Abdominal pain, bleeding, and abdominal mass were the most relevant symptoms. The median follow-up time was above 40 months and more than 50 % were alive. At study cutoff, only 2 patients had died. The most relevant concepts related to gastric GIST management were reviewed, which are of interest to any endoscopist.

text in

text in