Introduction

Anemia is the most common complication of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (1. It is associated with a more disabling disease2 with a significant impact on the quality of life3,4 and has historically received little attention from gastroenterologists5. Anemia is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as hemoglobin (Hb) levels < 12 g/dL in non-pregnant women and < 13 g/dL in men6. The European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) adopted the previous definition of anemia in a recent consensus, which recommends ruling out this complication in all individuals with IBD1.

The etiology of anemia in IBD is multifactorial. The most common causes are iron deficiency anemia (IDA) and anemia of chronic disease (ACD), which can coexist (mixed); other causes of anemia such as those associated with vitamin B12 or folic acid deficiency, or induced by drugs are less frequent7,8. In a systematic review of 17 articles with CD, the prevalence ranges between 4% and 67%9. Gisbert et al reported a 17% average prevalence of anemia in IBD, and figures of 16% were found in outpatients and 68% in hospitalized individuals10. IBD prevalence in Latin America is increasing11, and there is little data on the relationship between anemia and IBD. Two studies in Brazil found a prevalence of anemia of 21% and 24.6% in patients with IBD12,13. This study aims to determine the prevalence, associations, and treatment of anemia in a cohort of IBD patients in our center.

Materials and methods

The diagnoses of ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) were searched in the clinical records of the Hospital Pablo Tobón Uribe in Medellín, Colombia, until February 2019, considering the following codes: K500 CD of the small intestine, K501 CD of the large intestine, K508 other types of CD, K509 CD unspecified, K519 UC unspecified, and K518 other UCs. Data from adult patients with UC and CD, who attended the emergency department, were hospitalized, or were served by the outpatient clinic, were retrospectively analyzed to determine the presence of anemia.

Definitions of anemia

Anemia was diagnosed in patients with Hb levels < 12 g/dL for non-pregnant women and < 13 g/dL for men, according to the WHO recommendation6. IDA was considered at ferritin levels < 30 mg/L and normal C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, or in the case of ferritin < 100 mg/L and high CRP, but with a transferrin saturation percentage < 16%. ACD was defined as normal or elevated ferritin levels, normal average transferrin saturation percentage, and elevated CRP8. Anemia due to deficiencies of vitamin B12 (< 211 ng/mL) and folic acid (< 7 ng/mL) were defined when the levels were below the average level. Other measurements such as mean corpuscular volume (MCV), red blood cell distribution width (RDW), and percentage of reticulocytes were also incorporated to classify anemia14,15. Patients in whom anemia could not be defined due to insufficient data were excluded from the study.

Mild anemia refers to Hb levels of 11.0-11.9 g/dL in women and 11.0-12.9 in men, moderate 8.0-10.9 g/dL, and severe with levels < 8 g/dL, according to WHO recommendations1,6. UC activity was defined by the Truelove and Witts classification16, considering the activity at the time of the most severe episode of anemia for the analysis. According to the Montreal Classification17, the extent of UC was defined. The location and behavior of the CD were determined by the Montreal Classification17.

Data collection

A database with Excel format was built, collecting the following data from each patient for analysis:

Type of IBD (UC, CD, and IBD not classifiable)

Sex of the patient

Anatomical extension of the UC

UC activity

Location of CD

CD behavior

Cumulative medical treatment (5-aminosalicylic acid [5-ASA], steroids, immunosuppressants, biological therapy)

Surgical treatment

Hospitalization rate

Presence of anemia

Type of anemia

Severity of anemia

Treatment of anemia

The following measurements were considered to classify anemia: Hb, hematocrit, MCV, serum ferritin, percentage of transferrin saturation, and CRP. In patients with elevated MCV, we verified vitamin B12 and folic acid levels.

Statistical analysis

Absolute and relative frequencies were used for qualitative variables, and mean, standard deviation (SD), or median and interquartile range (IQR; P25-P75) were used for quantitative variables after verifying the assumption of normality with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests. The chi-square test (χ2) of independence was employed to compare two proportions, estimating the odds ratio (OR) with its appropriate 95% confidence interval (CI).

Ethical considerations

In this risk-free research, the patients’ medical records were reviewed, ensuring the confidentiality and privacy of the information collected. The project researchers adhered to the international principles of the 2013 Declaration of Helsinki in Fortaleza, Brazil, and Articles 10 and 11 of Resolution 008430/1993 issued by the Ministry of National Health of Colombia.

Results

In this retrospective, descriptive, analytical study, 759 patients who met diagnostic criteria for IBD were systematically included, of which 544 (71.6%) had a diagnosis of UC, 200 (26.3%) of CD, and 15 (1.9%) of unclassifiable IBD.

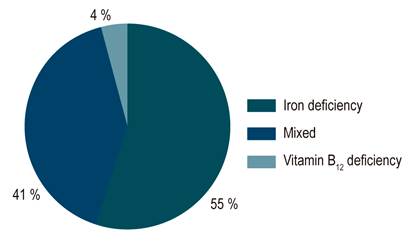

Anemia was documented in 185 of the 759 patients (24.4%) with IBD. In UC, 121 of 544 (22.2%) had anemia, compared with 65 of 200 patients (32.5%) with CD (OR: 0.684; CI: 0.456-0.96; p = 0.03). Regarding severe anemia, it occurred in 87 of 185 patients (47.0%) with IBD, 61 of 121 (50.4%) with UC, and 26 of 65 (40.0%) with CD. Of the total patients with anemia, 102 had IDA (55.1%), 74 (41.1%) had mixed anemia, and seven (3.7%) had vitamin B12 deficiency (Figure 1).

Of the patients with UC and anemia, 18.2% had proctitis, 28.1% left colitis, and 54.1% extensive colitis. A significant difference was found in comparing anemia in extensive versus non-extensive colitis (proctitis plus left colitis) (OR: 4.4; CI: 2.6-7.4; p = 0.001). Regarding UC activity, 5.0% were asymptomatic (S0), 14.0% had mild activity (S1), 15.7% moderate activity (S2), and 66.1% severe activity (S3). When comparing the presence of anemia in severe versus non-severe activity, we found a significant difference (OR: 4.95; CI: 2.87-8.51; p = 0.000).

Considering the location, the distribution of anemia in patients with CD was as follows: ileal (40%), ileocolonic (35.4%), colonic (20%), and upper gastrointestinal involvement (4.6%). No significant difference was found between colonic versus non-colonic location (OR: 1.2; CI: 0.66-2.19; p = 0.54). For CD behavior and the presence of anemia, it is inflammatory in 26.2% (B1), stenosing in 27.7% (B2), penetrating in 27.7% (B3), and perianal in 18.5%. The inflammatory behavior presented with anemia less frequently than the non-inflammatory behavior (B2 plus B3) (OR: 0.35; CI: 0.18-0.67; p = 0.000).

Patients with UC and anemia required more biological therapy than those without anemia (33.1% versus 14.4%); this difference was significant (OR: 2.29, CI: 1.46-3.58, p = 0.009). In CD, patients with anemia also required more biological therapy (61.5% vs 39.3%); however, this difference was not significant (OR: 1.56, CI: 0.94-2.6, p = 0.08). There was no significant difference in terms of the need for surgery in patients with anemia versus non-anemia in UC (11.5% vs 11.1%; OR: 1.04; CI: 0.55-1.95; p = 0.87), nor in CD (46.2% vs 34.8%; OR: 1.32; CI: 0.76-2.28; p = 0.32). Regarding hospitalization, patients with UC and anemia required more hospitalization compared to those without anemia (59.5% vs 47.0%; OR: 1.95; CI: 1.37-2.77; p = 0.000); this was not demonstrated in individuals with CD (72.3% vs 63.0%, OR: 1.14; CI: 0.72-1.82; p = 0.63) (Table 1).

Table 1 Clinical features of IBD and anemia

| CD | UC | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n) | 200 | 544 | 0.03 | ||

| Anemia | No anemia | Anemia | No anemia | ||

| 65 (32.5 %) | 135 (67.5 %) | 121 (22.2 %) | 423 (77.8 %) | ||

| UC extension | |||||

| - E1: proctitis + E2: left | 56 (45.9 %) | 0.001 | |||

| - E3: extensive colitis | 65 (54.1 %) | ||||

| CD location | |||||

| - L1: terminal ileum | 26 (40.0 %) | 0.54 | |||

| - L3: terminal ileum + colon | 23 (35.4 %) | ||||

| - L4: upper GI | 3 (4.6 %) | ||||

| - L2: colon | 13 (20.0 %) | ||||

| Severity of UC symptoms | |||||

| - Non-severe activity (S1 + S2) | 40 (33.9 %) | 0.000 | |||

| - Severe activity (S3) | 81 (66.1 %) | ||||

| Behavior of CD | |||||

| - B1: inflammatory | 17 (26.2 %) | 0.000 | |||

| - B2 + B3 + P | 48 (73.9 %) | ||||

| Biological/surgery/hospitalization for UC | Anemia | No anemia | |||

| - Biological | 40 (33.1 %) | 61 (14.4 %) | 0.009 | ||

| - Surgery | 14 (11.5 %) | 47 (11.1 %) | 0.87 | ||

| - Hospitalization | 72 (59.5 %) | 199 (47 %) | 0.000 | ||

| Biological/surgery/hospitalization for CD | Anemia | No anemia | |||

| - Biological | 40 (61.5 %) | 53 (39.3 %) | 0.08 | ||

| - Surgery | 30 (46.2 %) | 47 (34.8 %) | 0.32 | ||

| - Hospitalization | 47 (72.3 %) | 85 (63 %) | 0.63 | ||

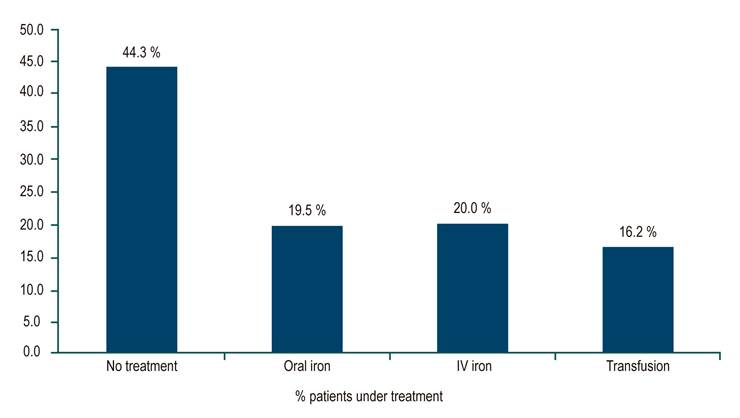

For the treatment of anemia and IBD, 82 of 185 (44.3%) patients with anemia did not receive treatment, 19.5% received oral iron, 20.0% intravenous (IV) iron, and 16.2% a transfusion (Figure 2). In the subgroup of patients with severe anemia, 24 of 87 (27.6%) were untreated, 12.6% received oral iron, 29.9% received IV iron, and 29.9% had a transfusion. No patient received erythropoietin.

Discussion

The prevalence of anemia in 759 adult patients with IBD, both outpatient and hospitalized, in our center is high (24.4%), and it is more frequent in CD (32.5%) than in UC (22.2%), as reported in the universal literature. A European meta-analysis with 2,192 patients found a prevalence of anemia in 24% of cases with IBD, 27% of cases with CD, and 21% of cases with UC18. The Norwegian IBSEN group also identified a higher proportion of anemia at diagnosis in CD (48.8%), compared to UC (20.2%)19. A Swedish study found 30% anemia in IBD patients at diagnosis, 42% in CD patients, and 24% in UC patients20. A more recent publication from the University of Pittsburgh detected a prevalence of anemia in patients with IBD of 33.2%, 34.3% in patients with CD, and 31.5% in patients with UC2. The ECCO-EPICOM cohort study noticed a higher prevalence of anemia in patients with CD of 49% and 39% in patients with UC during the first year after diagnosis21.

The high number of patients with severe anemia in our IBD patients (40.0%), compared with other series, was striking. In a multicenter study in nine European countries with 1,404 patients with IBD, 56% of individuals with at least moderate anemia (Hb <10 g/dL) were observed, but only 15% had severe anemia22. The severity of anemia was mild in 76.2%, moderate in 15%, and severe in 8.8% in a report of 193 cases associated with IBD in 55 centers in Germany23. It can be explained by the severity of patients with IBD who are cared for in our tertiary referral center. These two series are surveys of the participants, with no analysis of IBD severity in their patients.

On the one hand, our study demonstrated a predominance of IDA (55%) and mixed (41%) over other etiologies of anemia. In a Scandinavian study24, the etiology of anemia in IBD was IDA (20%), ACD (12%), mixed (68%), and a deficiency of vitamin B12 and folic acid (< 5%), as found in our study, but with a higher proportion of mixed anemia.

On the other hand, in our study, patients with UC and anemia presented with more strenuous activity (S3), more significant anatomical extension, and more disabling disease due to a higher hospitalization rate and greater use of biological therapy. In individuals with CD, anemia was associated with non-inflammatory behavior (stenosing or penetrating), so these patients are more complicated and have a worse prognosis than patients with inflammatory behavior. In the ECCO-EPICOM study already mentioned, patients with extensive UC and penetrating CD had a higher risk of anemia, just like in this study21. In the Swedish study, anemia was also associated with extensive UC20. Data from the University of Pittsburgh study above also show a significant correlation of anemia with higher rates of disease activity and hospitalization2.

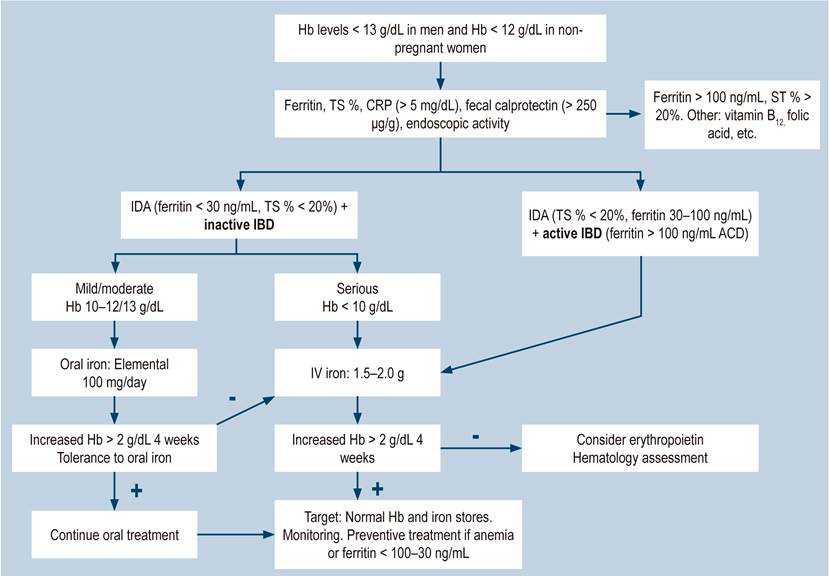

The ECCO guidelines1 recommend using oral iron in IBD patients with mild IDA defined by the WHO with Hb levels of 11-11-9 g/dL, whose IBD is clinically inactive and with good tolerance to the drug. IV iron should be considered as the first line of treatment in patients with intolerance to oral iron, active IBD, Hb levels < 10 g/dL, and in patients requiring erythropoietin1. A recent review article, considering the 2019 coronavirus disease pandemic (COVID-19), suggests using oral iron during these times in patients with IBD and mild and moderate anemia to prevent them from attending hospitals to receive parenteral iron and reserve the latter only for subjects with IBD and severe anemia (Hb < 8 g/dL)25.

In this study, 44.3% of the patients did not receive treatment regarding IDA. A high percentage of the subgroup of individuals with severe anemia did not receive it either (27.6%). We believe that the concept of asymptomatic anemia is still used in the medical body without considering the alteration in the quality of life that this complication entails. In a previous survey of gastroenterologists throughout Colombia, when asked what the best management of a patient with IBD and IDA <10 g/dL would be, 66% would treat it with oral iron, 15% with parenteral iron, 9% transfused iron, and 10% did not treat it26. In the German multicenter study mentioned above, only 43.5% of patients with IDA and IBD received treatment; from this portion, 56% were treated with oral iron, 15% with parenteral iron, and 10% in transfusion23. In the UK, a survey was conducted on outpatients with anemia and IBD who received oral iron; only 42% completed the treatment, but the treatment was not adequate for the control of anemia in 2 out of 3 patients27. In the European study above, 92% of IDA patients received iron supplementation, 67% oral iron, and only 28% IV iron, even though 56% had Hb < 10 g/dL21. A retrospective study conducted in the United States found that only 37% of anemic patients with IBD received oral iron, and 2.8% received IV iron during follow-up28. A global survey of patients with anemia and IBD found that 33% reported not receiving treatment for their anemia. Of those treated, 52% received oral iron, 27% IV iron, and 19% other types of supplements. Of the patients with oral iron, 74% were not satisfied with the treatment, while 72% were satisfied with IV iron29.

The Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America (CCFA) recently appointed a committee of experts to make recommendations and develop an algorithm for the screening, evaluation, intervention, and follow-up of patients with anemia and IBD30. A later publication assessed adherence to these recommendations and found that iron therapy in anemic patients increased from 30% to 80%, and the prevalence of anemia decreased from 48% to 25%. However, the percentage of iron deficiency screening did not change; only 20% of anemic patients underwent a ferritin measurement31. A recent review article recommends a treat-to-target approach for patients with IDA associated with IBD, as proposed for the treatment of IBD, divided into three steps: early detection, treat-to-target (normalization of Hb and iron stores), and strict monitoring (ferritin and transferrin saturation percentage every 3-6 months) due to the high risk of recurrence32.

Within the limitations of this study, it may contain interpretation biases, as it is a retrospective study based on data collected from the medical records. Additionally, this study was carried out in a tertiary referral hospital, a reference center for IBD patients throughout the country, with probably more severe and complicated patients than those from other centers in the country.

Conclusions

There is a high prevalence of anemia associated with IBD in our setting, which is more frequent in CD than in UC, consistent with other studies worldwide. It could be explained by insufficient diagnosis, ineffective treatment, and a lack of monitoring of these individuals with anemia. Anemia in patients with IBD is associated with greater severity of the disease. Additionally, the preferred route of administration of iron in IDA, both in this and other series cited, is oral, regardless of the severity of the anemia, the high percentage of intolerance to oral iron, and international guidelines. It is necessary to become more aware of this complication in patients with IBD and make more efforts in medical education to implement guideline recommendations and apply them to the early diagnosis, adequate management, and monitoring of these individuals. Nonetheless, the most important thing will always be the timely and adequate treatment of IBD to prevent this complication. A proposal for the management of anemia in patients with IBD is presented in Figure 3.

text in

text in