Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor known or GIST is the most common mesenchymal neoplasia of the digestive tract; however, their frequency represents only 0.1% to 3% of gastrointestinal neoplasms. Their incidence is 10 to 20 cases per million people, and approximately 10% to 30% are clinically malignant. Only 5,000 to 6,000 new cases per year are reported in the United States1. They may appear at any age but predominate in people aged 40 to 70 years2. About 65% of GISTs are found in the stomach, 25% to 40% in the small intestine, and 5% to 10% in the colon or rectum; its location in other digestive sites, such as mesentery, omentum or retroperitoneum, sites outside the gastrointestinal tract are infrequent and are reported to be less than 5%3-5. Surgical recession remains the gold standard for localized tumors, and pharmacological treatments are indicated for advanced stages of the disease. Those currently available have radically changed prognosis6.

Case presentation

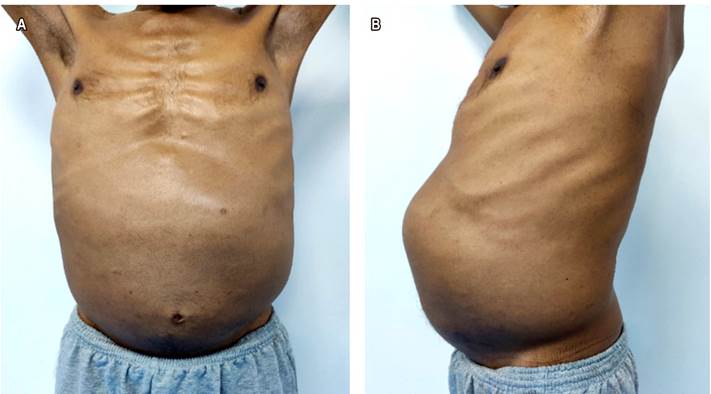

A 53-years-old male patient, with no personal, family or pathological surgical history, with a clinical picture of 2 years of evolution characterized by diffuse abdominal pain, abdominal distension, and weight loss of approximately 20 kg, which is why he went to private practice (Figure 1). The patient was admitted to the emergency room due to a 7-day clinical picture characterized by melena-type upper gastrointestinal bleeding 3 times a day without hemodynamic instability. It was also accompanied by abdominal pain, unquantified fever, headache, asthenia, loss of smell and taste for 5 days. On physical examination, pale skin and mucosa were found. On auscultation there were crackles in both lung fields, a distended abdomen with a visible and palpable mass in the epigastrium, mesogastrium, and left colonic frame.

Figure 1 A. The patient with abdominal distension can be observed. B. The dilated abdomen is observed with the presence of a mass at the level of the epigastrium, mesogastrium, and left hypochondrium.

The results of the laboratory tests were as follows: Hemoglobin: 2.60 mg/dL; Hematocrit: 10.30%; leucocytes: 9,600/mm3; neutrophils: 75%; platelets: 557,000; C-reactive protein (CRP): 10.6 mg/dL; albumin: 2.7 mg/dL; total proteins: 5.50; amylase: 94 U/L; lipase 552 U/L; D-dimer: 2989.7 µg/L; procalcitonin: 1.87 ng/mL; ferritin: 138 µg/dL; electrolytes: Sodium: 131 mEq/L, Potassium: 3.8 mEq/L, Chlorine: 95 mEq/L; normal renal function; normal clotting times; normal bilirubin; serological test for non-reactive syphilis (VDRL); prostate-specific antigen (PSA): 0.88 ng/mL; carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA): 1.06 ng/mL; alpha-fetoprotein (AFP): 1.57 ng/mL; carbohydrated antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9): 14.60 U/mL; tuberculin skin test or mantoux negative test; serology for non-reactive hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV); rapid test for 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19), immunoglobulin G (IgG), and M (IgM). Imaging tests included an abdominal ultrasound that reported a solid hypoechoic mass with regular contours arising from the greater curvature measuring approximately 23 x 13 cm with Doppler ultrasound, and increased vascularization.

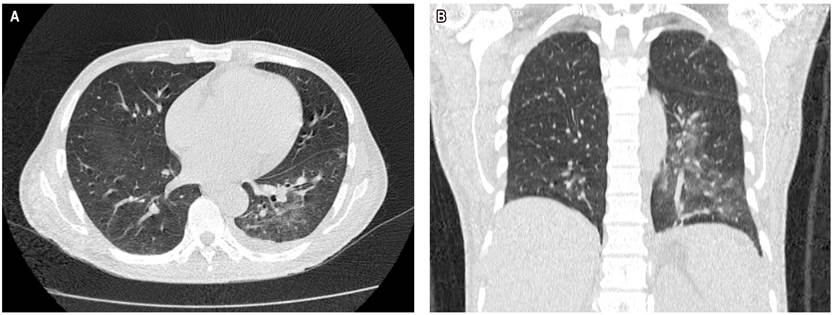

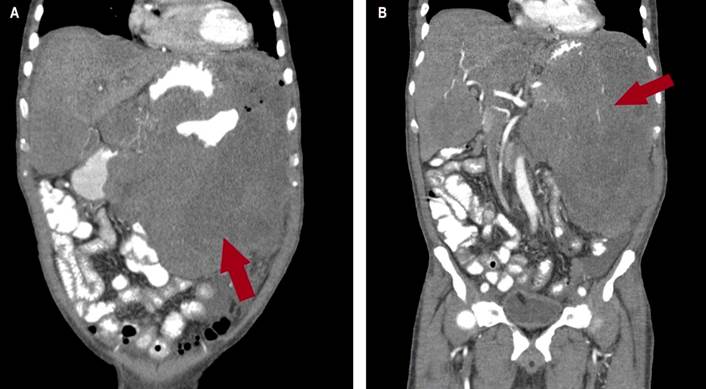

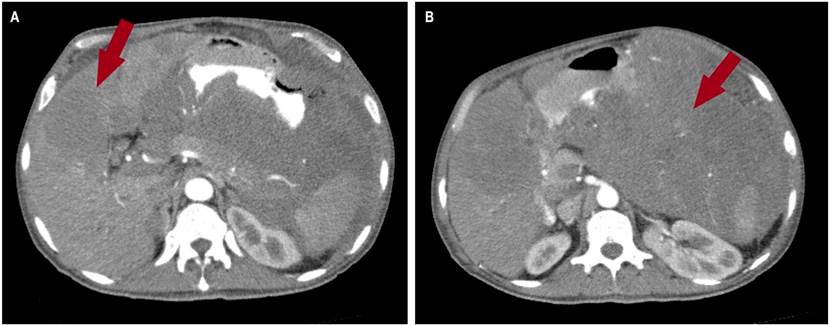

Chest computed axial tomography (CAT) revealed alveolar consolidation with ground glass infiltration in both lung bases and septal thickening (Figure 2). The CAT scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed an infiltrative tumor mass of apparent gastric origin measuring approximately 25 x 25 x 17 cm with extensive destruction of the wall and mucosa, with endoluminal infiltration and extragastric growth, liver metastasis (hepatomegaly with two hypoattenuating lesions of secondary appearance, measuring 72 x 41 mm and 86 x 75 mm respectively in hepatic segments IV and V, and infiltration of the hepatic hilum, resulting in dilation of the intrahepatic bile duct) infiltration of the spleen, pancreas, the mesenteric root, the greater omentum, the transverse colon, the small intestinal loops, the portal and the periaortic and pericaval lymph nodes, the largest measures 13 mm (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 2 Chest CAT scan. A. Transverse section showing alveolar consolidation, with infiltration of both lung bases in tarnished glass. B. Coronal cut in which alveolar consolidation is observed, with infiltration of the left pulmonary base in tarnished glass.

Figure 3 CAT scan of the abdomen. A and B. In the coronal section, a huge tumor mass with an infiltrative appearance of apparent gastric origin is observed, measuring approximately 25 x 25 x17 cm, causing extensive destruction of the wall and mucosa, endoluminal infiltration with extragastric growth and infiltration of the spleen, of the pancreas, the mesenteric root, the greater omentum, the transverse colon, and thin intestinal loops. It infiltrates the hilum of the liver, as seen in the red arrow.

Figure 4 CAT scan of the abdomen. A. A hypoattenuating lesion with a metastatic appearance measuring 72 x 41 mm, respectively, is observed at the hepatic segments V and IV. B. The coronal section shows a tumor mass with an apparent gastric origin infiltrative appearance, with extragastric growth with infiltration of the spleen, pancreas, mesenteric root, greater omentum, transverse colon, and thin intestinal loops and the hepatic hilum, as seen on the red arrow.

Concerning endoscopic studies, an upper digestive video endoscopy was performed in which an infiltrative lesion was observed at the level of the gastric body with a gastric ulcer scar with a histopathological report of gastric atrophy, lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate, proliferative cryptitis, and vascular congestion. Videocolonoscopy was incomplete due to extrinsic compression in the descending colon that prevented the passage of the equipment; diverticular disease was observed in the sigmoid colon with no signs of inflammation or bleeding. An ultrasound-guided percutaneous biopsy was performed on the left hypochondrium. The histology report informed a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), mitotic rate: mitosis/5 mm2, necrosis: unidentified, histological grade: low grade (mitotic rate ≤ 5/5mm2), evaluation risk: moderate (10%), immunohistochemistry: CD117 antigen (C-kit: receptor tyrosine kinase) with positive staining.

During his hospital stay, he received treatment for SARS-CoV-2 respiratory infection (COVID-19 pneumonia) with lopinavir/ritonavir 500 mg every 12 hours for 7 days, azithromycin 500 mg every day for 7 days, and ivermectin 6 mg 3 tablets (single dose).A satisfactory improvement was obtained.

A multidisciplinary team managed the treatment made up of internists, gastroenterologists, oncologists, pathologists, surgeons, imaging specialists, and nutritionists. It was determined that since it was an advanced disease with metastasis to different organs and without resection planes, he was a candidate for pharmacological treatment; therefore, it was started with imatinib and had a good response. He was discharged without complications, and he has monthly controls in external oncology consultations currently.

Discussion

GISTs are rare non-epithelial tumors of the digestive system. Mazur and Clark introduced the term stromal tumor in 1837, and it is currently proposed that GISTs originate from the interstitial cells of Ramon and Cajal7. GIST can be morphologically classified as fusiform (70%), epithelioid (20%), and mixed (10%), and may show muscle or neural strain. Unlike other mesenchymal tumors, GISTs express CD117 antigen (part of the C-kit receptor), which immunohistochemistry can demonstrate.

GISTs are submucosal lesions that appear to arise from the muscle of the intestinal wall, those of intramural origin are often projected exophytic extraluminal or endophytic intraluminal and may have ulceration of the overlying mucosa . Its size can be extremely variable, from small incidental cases to large masses, which almost always exceeds its vascular supply and leads to extensive areas of necrosis and hemorrhage8-9.

The clinical picture is variable, depending on the size of the tumor and the location. The most frequent symptoms are anemia, weight loss, gastrointestinal bleeding, abdominal pain, dysphagia, and symptoms related to the mass effect; they may present acute abdominal symptoms, obstruction, perforation, rupture, and peritonitis2. Concerning diagnosis, at least 10% to 30% is made incidentally, while 70% of patients have a wide range of clinical manifestations10.

CAT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are the first-choice imaging studies for GISTs. CAT with intravenous contrast allows the identification of possible hemorrhages, intratumoral calcification, preoperative staging, and evaluation of metastatic disease, as in hypervascular liver lesions. MRI is used to visualize tumors in the pelvic area and study the mesenteric and peritoneal extension. Although these imaging options serve to establish a presumptive diagnosis, none are precise 11-12. Positron emission tomography (PET) is generally not used for the evaluation of GIST, although it may be useful in early detection of tumor response to chemotherapy, as well as in evaluating erroneous metastatic lesions12-13.

The definitive diagnosis is obtained by histopathological analysis. Preoperative biopsy risks bleeding because the tumors are friable and to plan a definitive surgery is generally avoided. Fine needle aspiration (FNA) can provide adequate tissue to exclude other malignancies and, when combined with immunohistochemistry and reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis for KIT mutations, will generally confirm the diagnosis14.

Immunohistochemistry is used to confirm the diagnosis. The most widely used marker is CD117 in more than 95% of cases; other often positive markers are CD34 (70%-90%), smooth muscle actin (15%-60%), and rarely desmin13-15. Approximately 5% of GISTs have no detectable KIT expression.

Miettinen et al. analyzed in a study 1,765 cases of gastric GIST predominantly male with a mean age of 63 years old. The size of the tumor ranged from 0.5 to 44 cm with symptoms of gastrointestinal bleeding, and its most frequent location was the antrum (p < 0.001). KIT expression was detected in 91% of cases, CD34 in 82%, smooth muscle actin in 18% and desmin in 5% (p < 0.001). Mutations were detected in exon 11 of KIT in 119 cases and exon 18 in a total of 86 cases (p < 0.001)16.

Surgery is the gold standard for treating localized GIST, and biologic therapy with imatinib mesylate is recommended for cases with incomplete resection, unresectable tumors, and when tumors have progressed to metastatic disease. The relapse rate is not low in complete surgical resection, even after radical surgery. Low- and intermediate-risk tumors generally do well after surgery, while high-risk tumors generally reappear after resection and secondary surgery results are generally poor 4,12,17. Luigi Boni et al., in a GIST surgical resection study with experience of 25 patients, demonstrated that complete resection was achieved in 88% of cases. In contrast, radical resection was not possible in 12% of tumors from 1.2 to 30 cm, indicating that radical surgery offers the possibility of long-term survival17.

GISTs have become a multidisciplinary work model in oncology: the participation of several specialties (gastroenterologists, oncologists, pathologists, surgeons, molecular biologists, radiologists, and nutritionists) has anticipated advances in the understanding of this tumor and the consolidation of targeted therapy: Imatinib, as the first effective molecular treatment in solid tumors11. Sunitinib inhibits the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR), in addition to KIT and platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA), and it has demonstrated to be effective in patients intolerant or refractory to imatinib mesylate in more recent studies18. Radiation has been limited because the radiation dose required to control GIST probably exceeds the tolerance of surrounding tissues19.

Survival of advanced GISTs usually faces severe morbidity and short life expectancy, the average overall survival for unresectable or metastatic disease was about 12 months and 9 to 12 months for patients with local recurrence. Cases with unresectable hepatic and peritoneal GIST metastases have been difficult since malignant GISTs are refractory to conventional cytotoxic therapy.

In a study between 1987 and 2004 with 25 patients, who underwent surgical resection for GIST, Luigi Boni et al., indicated that the stomach was the most common site with complete resection in 88% of cases and in 12% radical resection was not possible. Overall survival at 5 years was 65% and 34%, respectively, with a statistically significant difference between tumors < 5 cm and > 10 cm in diameter and between complete and incomplete resection17.

Conclusions

GISTs are rare tumors, and symptoms are usually nonspecific. In most cases, the diagnosis is fortuitous, and the histology combined with immunohistochemistry and RT-PCR analysis for KIT mutations confirms the diagnosis. We present a case of giant GIST with extraintestinal and unresectable localization that was diagnosed by percutaneous biopsy and was treated with imatinib with a currently good evolution.

text in

text in