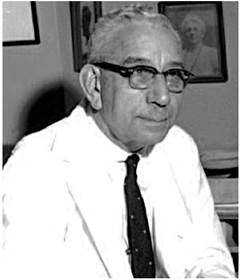

Burrill Bernard Crohn was born in New York on June 13, 1884, and died on July 29, 1983, at 99 (Figure 1)1. He was the son of a German-Jewish immigrant family who arrived in New York at the end of the 19th century1. At age 13, Burrill entered the City University of New York, graduating at age 18. In 1911, he earned his medical degree from Columbia University1. He then entered Mount Sinai Hospital for a 2-year training program. Emanuel Libman was his mentor1-3.

Crohn joined the hospital first as an intern in the Pathology department (chosen from 120 candidates) and then as an assistant. Later, he worked in the Chemical Physiology department, studying the pancreas function3.

In 1920, at the age of 36, Crohn was the head of the gastroenterology service at Mount Sinai Hospital. He was appointed president of the American Gastroenterological Association in 19351,3,4. In 1932 he presented a paper with Ginzburg and Oppenheimer originally called “terminal ileitis,” then changed it to “regional ileitis,” following the advice of Bargen from the Mayo Clinic2.

History

The Italian physician Morgagni made the first description of Crohn’s disease from a young patient autopsy with diarrhea and weakness in 17695,6. In 1813, two London surgeons, Combe and Saunders, reported the case of a patient who had thick ileal walls, ulcers in the cecum, and ascending colon. In 1913, Dalziel, a Scottish surgeon unknown to doctors at Mount Sinai Hospital, published a series about 9 patients who possibly had Crohn’s disease2,6 in the British Medical Journal.

While Crohn was studying the pancreas and its exocrine secretions, surgeon Berg performed the first successful subtotal gastrectomy to treat ulcerative disease3,7. Two young surgeons, Ginzburg (1898-1988) and Oppenheimer (1900 -1974) worked for some years on the diagnosis, treatment, and data collection of patients operated by Berg. They had intestinal obstructions, especially in the ileocecal region. When examining the resected areas, they were struck by the characteristic inflammation of these lesions, the intestinal walls thickness, and the absence of germs (especially tuberculosis), which could explain the clinical picture of the operated patients6,7.

According to Ginzburg, in 1931, after reviewing the anatomopathological studies of two patients operated by Berg, Crohn found that the latter’s team was collecting data on this type of ileitis. Crohn spoke with Berg to include him as an author in the publication of an article on the so-called “terminal ileitis.” Berg, who had already operated on 12 patients with these characteristics, declined the invitation because he did not participate in the article’s writing (he did not consider it ethical to appear as an author) but suggested that he request Ginzburg’s patient files7. Thus, all 14 patients in the original study were completed.

In May 1932, Crohn presented the manuscript at the American Medical Association (AMA) annual meeting. Neither Ginzburg nor Oppenheimer was mentioned at that time. This led Ginzburg to request a departmental meeting chaired by Berg. After hearing the parties involved, the committee that reviewed the case decided that Ginzburg and Oppenheimer7) should be placed as authors of the article in addition to Crohn.

The article was finally published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) in October 1932 and was twice as extensive as the original manuscript8. Crohn added this new information from his experiences and clinical observations. JAMA published the manuscript and put the authors’ names in alphabetical order, according to the custom of that time. This is why the eponym began to be forged in the minds of the article’s readers. Finally, in 1939, Armitage and Wilson proposed that it be called Crohn’s disease to simplify and unify the description of the disease and pay a well-deserved tribute to Crohn7.

If Berg had agreed to be part of the original article, we would be talking about Berg’s disease (as JAMA published in alphabetical order, Berg would have been the first author). The truth is that the eponym was assigned seven years later, not only based on the article. Crohn became a specialist in inflammatory intestinal diseases and gave lectures on the subject worldwide3,7. In addition, he accepted the critics and suggestions. An example of this is that during his presentations, Bargen, from the Mayo Clinic, suggested changing the term “terminal ileitis” to “regional ileitis” since all the patients were alive and in good condition. He found it suitable and changed the disease’s name6,7.

Crohn clearly described the disease and insisted that his name not be used as the eponym of this disease4. He finally gave up on this proposal. Crohn was a modest physician, devoted to the study and treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases, universally admired, and well-deserving of recognition as a true teacher1,3. He received numerous recognitions during his life.

Some of his hobbies were gardening, painting (watercolor), and a particular interest in the American Civil War3. Crohn was a great admirer of Abraham Lincoln. When President Eisenhower suffered from ileitis in 1956, he tried to assure the people that the president would recover without difficulty4.

His career is immortalized in the Burrill B. Crohn Research Foundation, based at the Mount Sinai Hospital1. In 1960, thanks to the publication of Lockhart-Mummery and Morson, the concept that Crohn’s disease could affect any area of the digestive system was generalized5.

texto en

texto en