Introduction

A liver abscess (LA) is a collection of pus surrounded by a fibrous capsule that, depending on its etiology, can be pyogenic or amoebic1. It occurs with low frequency in first-world countries, and between 5 and 22 cases are recorded per 100,000 hospital admissions, with a predominance of males between the third and sixth decade of life2. Mortality is reduced from 50% to 10% after percutaneous intervention guided by ultrasonography or tomography2.

The risk factors associated with amoebic liver abscess (ALA) are male gender, the third and fifth decades of life, alcoholism, oncological diseases, immunosuppression, and living in endemic areas, among others3.

Despite being an infectious pathology with accessible diagnostic methods and management options, LA continues to cause high morbidity and mortality in developing countries4. In the last century, there has been a decrease from 75%-80% to 10%-40% in mortality due to LA thanks to pharmacological advances, specifically in the area of antibiotics and interventional processes; however, it must be considered that timely diagnosis would contribute to improving prognosis and mortality5.

The cardinal elements to establish the diagnosis include clinical history, laboratory tests, and imaging studies. These elements are not enough to clearly differentiate between an amoebic abscess, a pyogenic abscess, or a malignant disease. With the existence of risk factors and a suspicious lesion, a potential amoebic infection can be assumed, as long as it is corroborated by other tests4.

Comorbidities such as the development of intra-abdominal sepsis without an apparent cause or malignant processes in advanced stages darken the prognosis and increase mortality more than the abscess concerned. The most frequent causes of death in this type of patient are usually sepsis and multi-organ failure3.

Our goal is to present the clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and specific therapeutic management of this patient and of a rare entity in our environment. It will serve as a guideline to conduct research on the diagnosis and treatment of this disease and as a reference for the future management of similar cases.

Clinical case

A 56-year-old black female patient was admitted to the Internal Medicine service for a 14-day history of dysentery with a severe compromise of her general condition, fever of 38-39 degrees, and pain in the right hypochondrium. Complementary tests were indicated, starting antimicrobial treatment with the clinical suspicion of complicated intestinal dysentery.

Complementary exams

Analytical studies

Table 1 shows the differential blood count.

Table 1 Differential blood count results

| Hb | 9.0 g/L |

| Leukogram | 15.8 x 109 |

| Polymorphonuclear leukocytes | 0.70 |

| Lymphocytes | 0.28 |

| Platelet count | 300 x 109 |

| Coagulation time | 10 minutes |

| Bleeding time | 1 minute |

| Prothrombin time | Control: 14 minutes, patient: 17 minutes |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | 107 mms |

| C-reactive protein | 25 mg/L |

| Blood glucose | 8.1 mmol/L |

| Creatinine | 58.7 mmol/L |

| Serum amylase | 86 pcs/L |

| Total bilirubin | 76 mmol |

| Total proteins | 45 g/L |

| Albumin | 26 g/L |

| Urea | 4 mmol/L |

| Uric acid | 296 mmol/L |

| Cholesterol | 3.0 mmol/L |

| Triglycerides | 1.22 mmol/L |

| GPT | 107 IU |

| GOT | 98 IU |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 370 IU/L |

| VDRL | Not reactive |

| HIV | Negative |

| Blood and stool cultures | Negative |

| Microscopic examination of feces | Positive for Entamoeba histolytica |

Hb: Hemoglobin; GOT: glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase or aspartate aminotransferase (AST); GPT: Glutamic pyruvic transaminase or alanine aminotransferase (ALT); HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; VDRL: Venereal disease research laboratory test. Source: Prepared by the authors.

Abdominal ultrasound

A heterogeneous liver is appreciated with two mixed images; the largest one of 110 x 84 mm with echolucent areas inside that could be related to degeneration, of average size, and does not exceed the costal margin. The gallbladder has no alterations. The right kidney measures 100 x 40 mm, and the 9 mm parenchyma has microlithiasis in the middle calyceal group without dilatation of the system. The left kidney measures 118 x 45 mm, and the parenchyma of 15 mm has no lithiasis or dilatation of the system. The bladder is empty. There is no free fluid in the abdominal cavity (Figure 1).

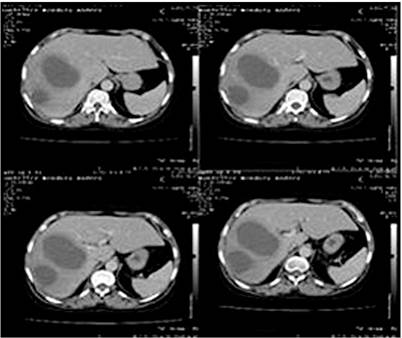

The liver is of average size with two closely related hypodense images and thick walls; the largest one of 114 x 92 mm, of liquid density, located in the right lobe immediately below Glisson’s capsule concerning subsegments VI and VII. The gallbladder has thin walls without stones, and there is no dilatation of the bile ducts. The pancreas and spleen are of standard size and density. The kidneys are of average size and position; there is good parenchyma without ectasia or lithiasis. The bladder is empty. There is no free fluid in the abdominal cavity and no intra-abdominal adenopathies (Figure 2).

Figure 1 Liver ultrasound. Diagnostic impression: Multiple LAs. Contrasted abdominal computerized axial tomography (CAT) No. 0077-19. Source: Owned by the authors.

Surgery

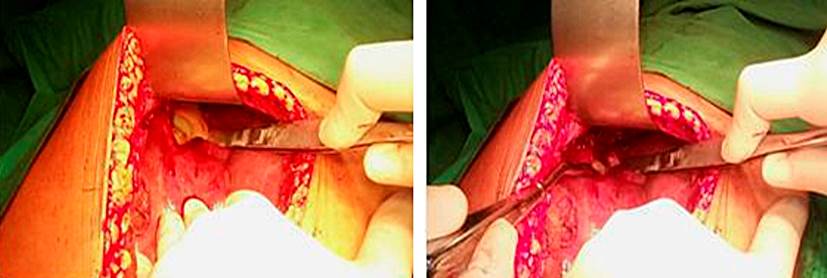

We decided to perform a laparotomy because of the poor response to the imposed medical treatment and the failure of the ultrasound-guided percutaneous puncture approach. A supraumbilical right transrectal incision was made, deepening it with the electrocautery by planes until reaching the abdominal cavity. An approximately 10 cm resistant area was found in the upper part of the right lobe of the liver in close relation to the diaphragm. It was carefully punctured, confirming the diagnosis that, due to the characteristics of the pus, it could be pyogenic and initially amoebic. A sample was taken for culture and antibiogram. The entire area of the abscess was subsequently unroofed, and 600 mL of creamy yellow pus was aspirated. The cavities were digitally explored for being multiloculated; it was washed with abundant physiological saline, carefully applying povidone-iodine to prevent contamination of the rest of the cavity (Figure 3). Counter-opening drainages were set, and the cavity was closed by planes. Subsequently, the patient went to the Intensive Care Unit for three days; then, she was transferred to the Intermediate Care Unit and to the Surgery Room, where the antibiotic treatment was completed. An antibiogram was received 72 hours after surgical drainage, which was positive for Escherichia coli.

Figure 3 Abscess cavity during laparotomy. Source: Owned by the authors. A medium-sized serous right pleural effusion (700 mL) was diagnosed and resolved with thoracentesis on the fourteenth day. The culture with antibiogram reported no bacterial growth. The patient evolved favorably and was discharged after 21 days.

Discussion

Amebiasis is the second leading cause of death from the parasitic disease worldwide; in Cuba, it has been proven that amebiasis is not one of the most frequent parasitisms, even though ALA is the most frequent extraintestinal manifestation of Entamoeba histolytica infection6.

Most LAs are polymicrobial, mainly caused by the combination of enteric and anaerobic bacteria1. Liver infection can originate from the bile duct (40.1%), portal vein (16.1%), infection of neighboring organs (5.8%), liver trauma (4.5%), cryptogenic (26, 2%), or other (7.3%), as the starting point of appendicitis, septic disease of the pelvis, pyogenic cholecystitis, diverticulitis, peritonitis secondary to hollow viscous perforation, infected hemorrhoids, and any other cause of septic origin7,8.

Within the bacterial etiology, Enterobacteria such as Escherichia coli and Klebsiella are recognized as capable of developing pyogenic abscesses, in addition to anaerobic enterococci and streptococci, among which Streptococcus milleri is the most frequent species. The immunosuppression of HIV infection, chemotherapy, and transplantation has increased the number of fungal abscesses and opportunistic germs4.

Poor sanitation, low socioeconomic status, decreased access to clean water, high population density, immunosuppressive conditions, HIV infection, and homosexuality are considered risk factors for acquiring amoeba infection, especially in the male sex. While in the female sex, protective factors such as iron deficiency due to menstrual loss, hormonal changes, and a lower tendency to use alcohol are described, causing minor hepatocellular damage (mainly to Kupffer cells)9.

Due to the effect of the mesenteric blood flow of the portal vein, there is a predisposition of more than 80% of the location of LAs in the right lobe, mainly in segments VI and VIII. Single abscesses can be of hematogenous or portal origin with a higher incidence between 60%-70%, while multiple abscesses have their origin in the bile duct with a lower incidence (30%)8.

The symptoms recorded in a pyogenic liver abscess (PLA) have been diverse, mainly due to its pathology. PLAs have shown clinical variability over time. Fever, jaundice, and pain associated or not with cholangitis or pylephlebitis, as traditionally known, have given way to subclinical forms3.

There are symptomatologic differences concerning single or multiple abscesses, the latter with a more significant systemic impact. The clinical differences between amoebic and pyogenic abscesses are not notable since more than 90% of patients present with fever, weight loss, malaise, abdominal pain, chills, myalgia, headache, pruritus, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and in the most severe cases, shock and mental confusion3.

Jaundice and right upper quadrant pain, aggravated by percussion, are some signs found on physical examination. Nonetheless, other patients only present with fever, before which we must think of an LA, especially if the fever origin is unknown. In addition, respiratory symptoms are apparent, such as cough and pleuritic pain radiating to the right shoulder when in the presence of subdiaphragmatic abscesses8. In both types of abscesses, 80% of patients have symptoms established in days or weeks prior to diagnosis, typically in less than two to four weeks7.

Leukocytosis associated with anemia and accelerated sedimentation rate is frequently associated with LA. In liver function tests, enzymes sometimes appear elevated, mainly transaminases, alkaline phosphatase, and bilirubin. Our results showed elevated liver enzymes and a higher frequency of hypoalbuminemia associated with pyogenic abscesses compared to other studies8.

Abdominal ultrasound is a non-invasive, low-cost method with a sensitivity that ranges between 85%-95%, making it the diagnostic method of choice. Besides, it can be used to guide the aspiration and culture of the abscess. CT has a higher sensitivity (95%-100%) and helps identify other intra-abdominal pathologies10.

There is a broad spectrum within the differential diagnosis, so a high index of suspicion is needed after a thorough history and physical examination. Possible causes can be infectious and non-infectious, including5 Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, acute leukemia, pathology of the bile duct (cholangitis and cholecystitis), acute diverticulitis, acute appendicitis, visceral perforation, mesenteric ischemia, acute pancreatitis, and pulmonary embolism.

Treatment and mortality in patients with PLA were addressed in 1938 by Ochsner and DeBakey, who established surgery as the treatment of choice; however, in recent decades, new diagnostic and non-surgical treatment options have been introduced11.

Management should include drainage of the abscess, whose techniques include percutaneous drainage guided by ultrasound or tomography, catheter drainage, drainage by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), specifically in those cases with an obstruction of the bile duct attached to the stent placement, and laparoscopic drainage or open surgical drainage3.

There are differences in the management of abscesses larger than 5 cm. Some authors prefer surgical intervention to percutaneous drainage with a lower range of treatment error, although there are no differences in the clinical picture’s morbidity, mortality, and duration. The conduct of LA drainage varies depending on their size; if they are smaller than 5 cm, it is more feasible to perform needle aspiration or catheter drainage. When the size is larger than 5 cm, placement of a drainage catheter is preferable since needle aspiration has been associated with a therapeutic failure of up to 50% in these cases12.

The established antibiotic regimen and its duration may vary depending on the culture results, the number of abscesses, their size, and clinical improvement and should last between two and four weeks. The administration of antibiotics with combined antimicrobial therapy (third-generation cephalosporins plus metronidazole or piperacillin-tazobactam) is only effective in Las smaller than 5 cm in diameter, which report Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Bacteroides, enterococci, and anaerobic streptococci as causative germs. Vargas et al describe a high resistance to fluoroquinolones and ampicillin5.

Mora et al13 reported a clinical case of LA in which the causal germ was of the genus Pediococcus, specifically Pediococcus pentosaceus. It was initially managed with the administration of piperacillin-tazobactam and metronidazole, puncture, and percutaneous drainage, whose evolution was torpid. Thus, it was necessary to make gradual readjustments in its treatment until administering meropenem and vancomycin to obtain a favorable evolution.

The indications for surgical aspiration combined with antibiotic therapy include: 1. High possibility of rupture when it comes to a cavity larger than 5 centimeters; 2. Left lobe abscesses have a high risk of communicating with the pericardial sac; 3. Failed response to treatment after one week11.

In the last three decades, percutaneous drainage has been displacing traditional surgical drainage coupled with the use of antibiotics to become the treatment of choice, except in cases of multiple abscesses difficult to access or when medical treatment has not shown a notable improvement12. Combined management in any of the three ways (aspiration plus direct drainage, drainage plus percutaneous catheter placement, or surgery) is reported in 52% of studies, most of which used surgical management10.

The combination of laparoscopic drainage and antibiotic therapy is possible in selected patients or those in whom percutaneous drainage has failed. Laparotomy is reserved for cases with a greater possibility of opening the abscess to the peritoneal cavity or when the necessary conditions to perform percutaneous puncture or laparoscopic access are available14.

In other situations, including multiple abscesses, multilocular abscesses with dense content, poor response after seven days of percutaneous drainage, dimensions equal to or greater than 110 mm or more than 500 mL, those adjacent to the diaphragm, those of the left lobe due to the risk of pericarditis, failure of the previous methods, and patients with more than one criterion, surgical drainage is the treatment of choice14.

In 50% of patients, the liver returns to its standard size after a few weeks, with radiological improvement observed between three and nine months later15. Between 10% and 20% of patients exhibit complications related to an extension to neighboring structures or rupture of the abscess, mainly to the pleuropulmonary space (pleural effusion or empyema), and less frequently, subphrenic abscess, peritonitis, pericarditis, and the haemobilia. Its mortality is reduced with early diagnosis and adequate treatment. Factors that increase the risk of death include shock, adult respiratory distress syndrome, disseminated intravascular coagulation, immunosuppression, severe hypoalbuminemia, diabetes, ineffective surgical drainage, and malignancy16. In Cuba, the advantages of non-surgical interventional management have also been observed as a management option combined with antibiotic therapy6.

In our case, the management of combined antibiotics (third-generation cephalosporins, aminoglycosides, and metronidazole) was chosen, which covered the amoebic and pyogenic etiology from the beginning with poor results. The dimensions of the abscess, its proximity to the diaphragm, the failure of the ultrasound-guided percutaneous puncture approach, and the patient’s clinical deterioration made laparotomy necessary.

texto en

texto en