Introduction

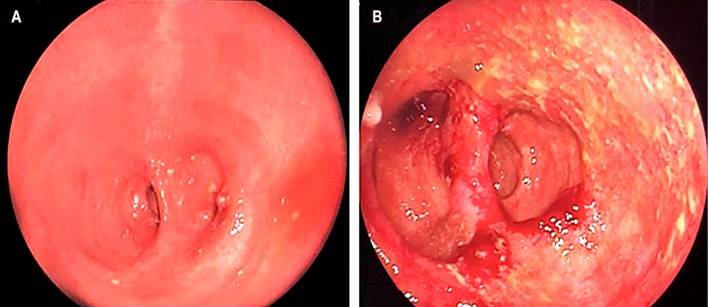

It is presumed that between 6% and 15% of patients with ulcerative colitis will require surgical management despite advances in drug therapy; this occurs mainly in cases of refractory disease or the development of colorectal carcinoma during the disease1. Total proctocolectomy with an ileal pouch is considered the first line of surgical treatment. Pouchitis is the most common complication, affecting approximately 20% of patients during the first year and nearly 50% in the first five years of the surgical procedure2,3. Different techniques for the creation of the ileal pouch and associated complications classified as early (in the first thirty days of the procedure) or late have been described4 (Figure 1, Table 1).

Table 1 Complications associated with the creation of the ileal pouch

| Early |

|---|

| Hemorrhage (suture line, pouch ischemia, intra-abdominal bleeding, intramural bleeding) |

| Sepsis (anastomotic leak, infected hematoma) |

| Portal thrombosis |

| Late |

| Intestinal obstruction |

| Pouch dysfunction Mechanical causes (obstruction, stricture) Pouchitis Cuffitis Irritable pouch syndrome |

| Pouch failure |

| Dysplasia or malignancy |

| Infertility |

Source: Modified from4.

Figure 1 Types of ileal pouches. A. Ileal J-pouch. B. Ileal W-pouch. C. Ileal S-pouch. Source: Modified from4.

CASE PRESENTATION

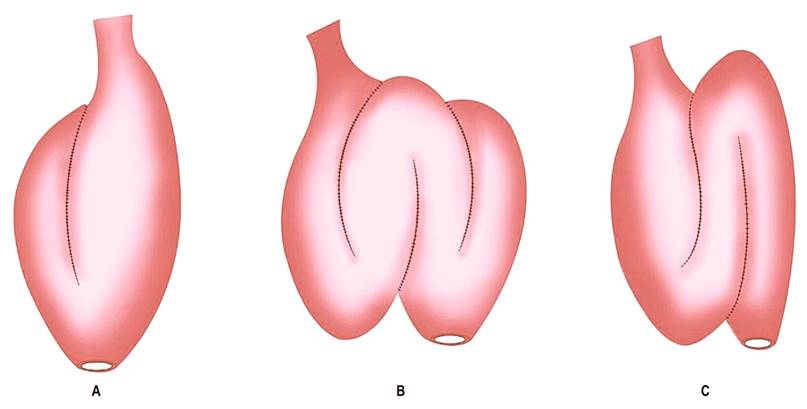

We present the case of a 32-year-old female patient diagnosed with refractory ulcerative colitis (RUC) since 18, who required a total proctocolectomy with an ileal J-pouch and a protective ileostomy in 2010. Restitution of bowel transit was performed six months later. Since the first year of the surgical procedure, the patient had had between 2 and 3 episodes of pouchitis, for which she received antibiotic treatment (ciprofloxacin/metronidazole) that ultimately resolved the symptoms. In May 2020, the patient consulted again due to increased stool frequency (>10 in 24 hours), abdominal pain and bloating, rectal bleeding, and fecal incontinence. It was regarded as a new episode of pouchitis, so treatment with ciprofloxacin was started at 500 mg every 12 hours. An endoscopic assessment was requested and performed two months later, with evidence of multiple fibrin-covered ulcers and some pustular elevations with pseudomembranous formation. Biopsies were taken (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Endoscopic findings of pouchitis: edema, erythema, mucosal friability, fibrin-covered ulcers, and pustular elevations. Source: Authors’ archive.

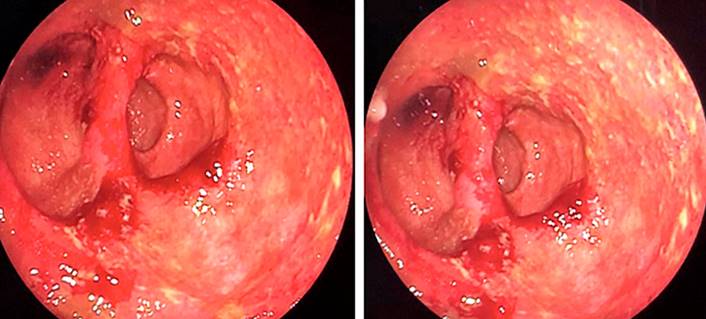

The histopathological report listed epithelium with changes marked by chronicity, including architectural distortion, lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, intestinal metaplasia, and decreased intraglandular mucin with extensive neutrophil polymorphonuclear activity, crypt abscesses, and viral cytopathic changes compatible with cytomegalovirus (CMV) (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Histological findings in cytomegalovirus pouchitis. Mixed inflammatory infiltrates and cytomegalic cells with an enlarged nucleus, suspicious for cytomegalovirus inclusion (arrow). Source: Authors’ archive.

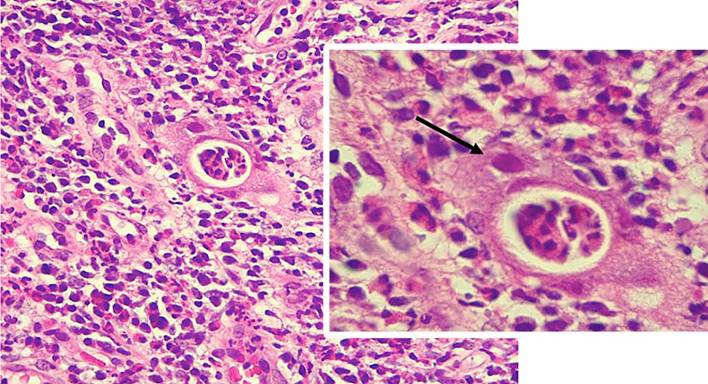

The patient remained symptomatic, did not respond to the antibiotic initially administered, and presented with an exacerbation of symptoms, so we decided to start antiviral treatment with intravenous ganciclovir plus ciprofloxacin. Twenty-one days of treatment were completed with a favorable clinical response and no documented adverse reactions to its administration. The patient was discharged due to the complete resolution of symptoms. Endoscopic follow-up was performed three months later, finding a noticeable improvement compared to the initial study (Figure 4). Currently, the patient remains asymptomatic and is being treated with oral rifaximin.

Discussion

Pouchitis is a non-specific inflammation of the ileal pouch whose pathogenesis is unclear. Nevertheless, it could be related to alterations in the microbiota of the pouch as a result of fecal impaction in genetically susceptible individuals with an altered immune response5. Typical symptoms are watery diarrhea, abdominal pain, tenesmus, urgency, fecal incontinence, and, less frequently, rectal bleeding; however, this clinical scenario is not specific. The diagnosis must be confirmed by endoscopic and histological changes to rule out other entities, such as irritable pouch syndrome or mechanical conditions associated with the surgical procedure6. The main endoscopic features include erythema, edema, friability, hemorrhage, loss of vascular pattern, erosions, and ulcerations7 (Figure 2).

It is advisable to take 4 to 6 pouch biopsies even in case of mild or absent inflammation (in mild forms, the endoscopic appearance may be normal) and 4 to 6 biopsies of the afferent loop to detect granulomas, ischemia, CMV inclusions, dysplasia, or ischemia8,9. Typical histological findings are acute inflammation with neutrophil infiltration, crypt abscesses, or mucosal ulceration often associated with chronic changes such as villous atrophy, crypt distortion, and chronic inflammatory infiltrate10 (Figure 3).

Once the diagnosis is made, the degree of disease activity should be established using the Pouchitis Disease Activity Index (PDAI). This index consists of a numerical scale that quantifies the severity of pouchitis and considers the clinical, endoscopic, and histological findings for its calculation11. Diagnosis requires a score ≥ 7. Since the histological report is not always available, the modified PDAI that only includes clinical and endoscopic criteria has been designed; the diagnosis, in this case, requires a score ≥ 512 (Table 2).

Table 2 PDAI index. Pouchitis defined as PDAI ≥ 7 or modified PDAI ≥ 5

| I. Clinical criteria | |

|---|---|

| Number of bowel movements/day above normal | |

| Same | 0 |

| 1-2 more | 1 |

| Three or more | 2 |

| Blood in the stool | |

| No/Occasional | 0 |

| Daily | 1 |

| Fecal urgency or abdominal cramps | |

| Absent | 0 |

| Occasional | 1 |

| Usual | 2 |

| Fever > 38ºC | |

| No | 0 |

| Yes | 1 |

| II. Endoscopic criteria | |

| Edema | 1 |

| Granularity | 1 |

| Friability | 1 |

| Loss of vascular pattern | 1 |

| Mucous exudate | 1 |

| Ulceration | 1 |

| Edema | 1 |

| III. Histological criteria | |

| Polymorphonuclear infiltration | |

| Mild | 1 |

| Moderate + crypt abscesses | 2 |

| Severe + crypt abscesses | 3 |

| Low power field ulceration (average) | |

| < 25% | 1 |

| 25%-50% | 2 |

| > 50% | 3 |

Source: Taken from12.

Pouchitis can be classified by the duration of the symptoms, as acute or chronic (longer or shorter than four weeks); by the response to antibiotics, as responders, dependent, or refractory; by the frequency, as infrequent, recurrent, or continuous (greater or less than three episodes per year); and by its etiology, as idiopathic (most cases) or secondary. The latter includes infectious causes (Clostridium difficile, CMV), mechanical complications related to the surgical procedure (ischemia or stricture), use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or Crohn’s disease of the pouch6,10. The probability of pouch failure is 3%-15%, mainly in patients refractory to antibiotic treatment; in this case, surgical management with resection of the pouch, a definitive ileostomy, or both may be required6,13.

Antibiotics are the first line of treatment, with response rates close to 80%; metronidazole and ciprofloxacin have proven effective14. Relapse after a first episode of pouchitis is typical, and about 20% will develop frequent relapses or refractory disease2. Those patients with three or more annual episodes despite antibiotic treatment are considered antibiotic-dependent15, and probiotics are an effective option to maintain remission induced by antibiotic therapy16,17. Other maintenance therapies, such as oral or topical rifaximin and mesalazine, have also been used and could be considered; however, the evidence is of low quality to advise its widespread use18,19. In these patients, as in those who do not initially respond to antibiotic treatment, secondary causes should always be ruled out, and if documented, specific treatment should be indicated2.

CMV infection is uncommon as a cause of pouchitis; nonetheless, it should be considered in patients who do not respond to initial antibiotic treatment. CMV is a double-stranded DNA virus belonging to the Herpesviridae family; humans are its only natural host, and ubiquitous in the adult population. Primary infection generally occurs in childhood and is usually asymptomatic in immunocompetent patients, followed by an indefinite period of residence in endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and cells of the myeloid lineage. Seroprevalence varies depending on age and ethnicity, with percentages close to 90% in older adults20. CMV lesions may occur due to primary infection or reactivation of the latent virus. Reactivation occurs mainly in individuals with compromised cellular immunity; in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, the known risk factors for reactivation are advanced age, female sex, severe disease, and recurrent use of corticosteroids21,22. Active CMV infection implies that it is detectable in blood or pathological specimens (biopsy), including histology, immunohistochemistry (IHC), or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in tissue23.

Diagnostic tests include serological tests such as the measurement of antibodies, antigenemia, and C-reactive protein (CRP) in blood. Immunoglobulin G (IgG) diagnoses previous contact, while IgM is very sensitive and specific for detecting acute infection or reactivation when accompanied by viremia23. PCR in the blood can be diagnostic, but no cut-off point differentiates latent from active infection. The sensitivity and specificity of antigenemia have been reported at 47% and 81%, respectively20,24. Hematoxylin/eosin staining offers high specificity (92% to 100%) but low sensitivity (10% to 87%); IHC increases sensitivity from 78% to 93%25.

Tissue PCR has high sensitivity (92%-96%) and specificity (93%-98%) and can be considered when IHC is negative in cases with high suspicion of CMV infection26. Despite the high sensitivity and specificity of the culture (45%-75% and 89%-100%, respectively), it lacks clinical utility since the results can take between two and four weeks20.

Ganciclovir is the treatment of choice and must be administered as an intravenous infusion due to its low bioavailability by the oral route. The recommended dose is 5 mg/kg twice a day for 2 to 3 weeks; it can induce severe complications such as myelosuppression, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia, as well as headache, nausea, vomiting, and hypotension, so these effects should be monitored regularly20,21. This treatment usually requires hospitalization; however, it could be replaced by oral valganciclovir, although its efficacy is controversial20. There are data in the literature on follow-up after antiviral therapy. Still, endoscopic assessment is suggested to ensure mucosal healing, especially when there is suspicion of Crohn’s disease or involvement of the afferent loop on initial endoscopy20,21.

Conclusions

Total proctocolectomy with ileal pouch is the treatment of choice for RUC, and pouchitis is the most frequent complication in these patients. CMV infection is rare, and a high index of suspicion is required for its diagnosis; however, symptoms in immunosuppressed individuals or those who do not respond to conventional treatment should always lead to suspicion of this condition.

text in

text in