Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Agronomía Colombiana

Print version ISSN 0120-9965

Agron. colomb. vol.32 no.3 Bogotá Sept/Dec. 2014

https://doi.org/10.15446/agron.colomb.v32n3.46240

Doi: 10.15446/agron.colomb.v32n3.46240

1 Department of Agronomy, Faculty of Agricultural Sciences, Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Bogota (Colombia). ebenitez@unal.edu.co

Received for publication: 23 October, 2014. Accepted for publication: 27 November, 2014.

ABSTRACT

This article presents an overview of the main results obtained from research on oil palm bud rot. Aetiologic studies with biotic and abiotic approaches were explored, aiming for a model that would help in the understanding of the ethology of this disease. It also discusses how the results of the studies are contradictory and how the arguments for biological causes have not shown progress. Furthermore, the results of measuring the influence of abiotic factors, where there is greater consensus, are discussed; however, there is controversy due to the fact that different researchers placed different weight on the final model of this disease. This situation has led to controls being directed toward potential pathogens associated with the disease, as determined by circumstantial evidence, wherein the positive or negative response to the control may be confused with extrinsic factors such as disease escape or foci formation. Even the role played by the insect Rhynchophorus palmarum (L.) in the death of palms affected by this disease is in doubt. Finally, this paper shows how the process of general disease research has important biases arising from the risk aversion of palm producers or the lack of continuity in results obtained by different research groups.

Key words: epidemiology, tropical diseases, aetiology, abiotic stress, biotic stress.

RESUMEN

En este artículo se exploran los estudios etiológicos bajo enfoques bióticos y abióticos de la enfermedad pudrición del cogollo de la palma de aceite. También se muestran las diferencias en los análisis y resultados de las investigaciones en la etiología biótica, así como sus sesgos. Por otro lado se discute sobre los resultados que miden la influencia de factores abióticos, resultados que tampoco se libran de ser controvertidos y que dependiendo del investigador reciben diferentes niveles de ponderación en el modelo final de la enfermedad. Esta situación ha generado que los controles dirigidos a los posibles patógenos asociados a la enfermedad, se tengan que basar en evidencias circunstanciales, donde la respuesta se confunde con factores extrínsecos a esta. Inclusive la responsabilidad del insecto Rhynchophorus palmarum (L.) en la muerte de las palmas afectadas por la enfermedad se puede considerar que está en duda. Se muestra finalmente cómo el proceso de investigación general de la enfermedad presenta sesgos importantes que surgen de la presión de los agricultores a este sistema, el cual se da ante la inminencia de pérdidas económicas o a la falta de continuidad en el aprovechamiento de los resultados obtenidos por diferentes grupos de investigación.

Palabras clave: epidemiología, enfermedades tropicales, etiología, estrés abiótico, estrés biótico.

Introduction

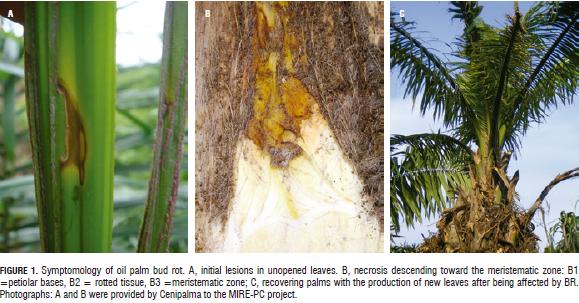

Oil palm bud rot (BR) is a disease that destroys the young tissue of palms. The initial lesions (Fig. 1A) descend from the middle of unopened internal leaves (spears) towards the meristematic zone. The progress of the lesions leads to colonization by several pathogenic and saprophytic organisms, thereby completing the symptomatology (Sarria et al., 2008).

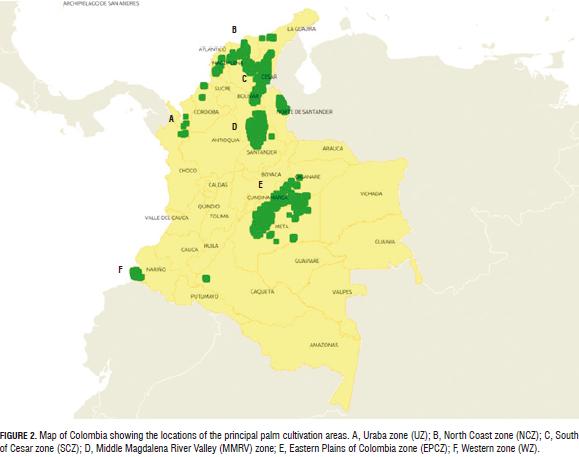

Depending on the quantity of affected tissue and whether or not the infection reaches the meristem (Fig. 1B), BR can be a lethal disease (lethal bud rot, LBR) or a disease that only inhibits the growth of the palm for some period (Chinchilla and Durán, 1998). The former has been seen in the Brazilian and Ecuadorian Amazon, certain zones of Suriname, and the Colombian western zone (WZ) (Franqueville, 2003; Corredor et al., 2008). The latter (Fig. 1C) has been reported in the Eastern Plains of Colombia (EPC) (Fig. 2). A unique case occurred in the Middle Magdalena River Valley (MMRV), where the infections did not reach the meristem, but, despite this, effective recovery did not occur (Benítez, 2015). It was stated that the insect Rhynchophorus palmarum L. (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) was the reason why the palms were unable to recover, due to its direct damage to the bud (Hurtado et al., 2009; Aldana de la Torre et al., 2010; Quintero, 2010; Montes and Ruiz, 2014).

Despite the fact that BR symptoms are easy to recognize in productive plantations, there are two main reasons why diagnostic confirmation through the isolation of the causal agent with Koch’s postulates has not been possible: first of all, contradictory studies on the causal agent and second, the fast growth of saprophytic and opportunistic organisms over rooted tissue make the isolation of any causal agent difficult. This is why only when the disease has disseminated throughout a population and formed foci is it possible to differentiate it from other similar types of pathologies that have a lesser impact on the crop, such as juvenile disease, spear rot (Martínez et al., 2014), or abiotic disorders (Renard and Quillec, 1984; Villanueva, 1988; Breure and Soebagjo, 1991; Louise et al., 2007). This fact has led to the development of breeding programs in Colombia that use epidemiological approaches rather than direct inoculation for resistance selection (Navia et al., 2014).

Economic importance

The Colombian association of palm producers recognizes the fact that one of the biggest challenges for sustainability in this agroindustry is diseases control (Fedepalma, 2007; Kraul, 2010). It was reported that, in 2007, the two more notable diseases, lethal wilt (LW) and BR, resulted in losses of up to US$58.5 million (Fedepalma, 2007) through a reduction in oil production that oscillated between 2.3 and 9.9% in the case of BR (Acevedo et al., 2000) and through palm deaths caused by LBR and LW.

Plantations have been devastated by BR in the WZ, affecting the economy of this region. Reports for 2008 stated that 1,540 direct jobs were lost due to this disease, with reductions in the potential revenue of the region of up to 46%, amounting to close to US$ 120 million (Corredor et al., 2008), and, according to Fedepalma (2014a) for the regions Puerto Wilches (Santander) and Cantagallo (Bolivar) in MMRV, BR has resulted in losses of more than US$2.85 billion and more than 8,000 direct and indirect jobs.

History

BR, as compared with other plant diseases, has had a short and accidental history that started at the beginning of the twentieth century. Reinking made one the first reports in 1928 in Panama (Franqueville, 2003); nevertheless, Van Hall mentioned a similar symptomatology in India starting in 1920 (Van Hall, 1922). This disease has affected palm crops in Latin American, part of Africa (Franqueville, 2003) and apparently in India (Van Hall, 1922). Its effects have varied from lower production to the complete destruction of crops. In Colombia, recent reports have been made for the MMRV zone where, in 2006, the first foci for the disease appeared (Silva and Martínez, 2009). This disease has demonstrated different levels of aggressiveness throughout the geography of Colombia. It started in the UZ in the 1960s, where its effects were devastating (Franqueville, 2003). Afterwards, the disease appeared in the 1990s in the EPCZ (Tovar, 2014) and, although its incidence almost reached the entire zone in a period of three to four years (Tovar, 2014), the recovery of the palms was high. This phenomenon has been explained by the fact that, in this zone, the wet and dry seasons are well-defined; however, this explanation has not been demonstrated. In this region, the producers initially started to eradicate diseased palms, but, once recovery of the palms was observed, they developed a practice called surgery, which consisted of removing all of the affected tissue in the bud area with the objective of giving way to healthy tissue and favoring the natural processes of recovery in the diseased palm. This practice was implemented by producers in subsequently affected zones: the MMRV and WZ zones. However, the expected recovery was not seen in these two regions. It was speculated that the failure of this practice in these two zones was associated with the fact that, in the first years of the disease’s appearance, there were historically high rainfalls resulting from the La Niña phenomenon between the years of 2005 and 2008 (NOAA, 2014) and that there was a lack of coordination between the affected plantations, which impeded the implementation of opportune, coordinated and effective regional activities. At the beginning of the current decade, this disease was reported in the NCZ; nevertheless, the evolution of this disease in this zone has yet to show the exponential behavior that has been seen in the rest of the country. This has facilitated the development of regional work incentives that, with coordination among the plantations, generate preventive and curative management plans, similar to the work done by plantations in the SCZ under the regional initiative called "Palmeros Unidos" (Fedepalma, 2014b).

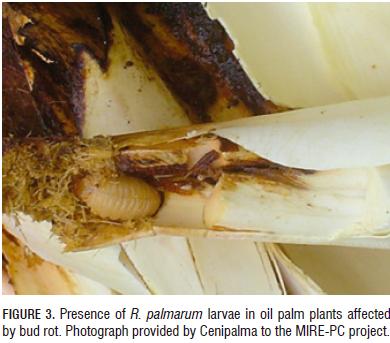

Parallel to the advance of the disease, an interaction has been reported with R. palmarum, wherein palms are being destroyed through the invasion of this insect (Martínez et al., 2009). In this sense, R. palmarum adults are considered an opportunistic organism that detect the odor of rotting tissue and initiate the colonization of palm buds. Their larvae can destroy internal structures and eventually reach the meristem, resulting in the death of the palm (Fig. 3). However, to date, no study has been conducted to measure their impact on palm crops and those that have been published only offer circumstantial evidence. On the other hand, in evaluations carried out by the first author (unpublished data) on 11,000 palms affected by this disease in the MMRV zone between 2008 and 2009, in the exponential phase of the epidemic, only 2.2% were infested with this insect: 0.3% with pupae, 0.9% with larvae, and 0.9% with adults, which is a very low incidence rate that did not demonstrate the superposition of generations and that, as a result, was not conclusive for determining this insect as a significant factor in palm deaths.

Aetiology of the disease

The history of the aetiology of this disease has been approached from two angles: the infectious approach with Koch’s postulates and the abiotic approach that considers BR a physiological result of the palm's interaction with adverse environmental conditions. Franqueville (2003); Bergamin Filho et al. (1998), Franqueville (2003), and Bergamin et al. (1998) argued for abiotic origins; however, Van der Lande (1993) and Van der Lande and Zadoks (1999) concluded that this disease is biotic in nature.

Biotic aetiology

In the biotic discussion, there has been an abundance of hypotheses, arguments, contradictions, and conclusions for the responsibility attributable to the organisms involved in this pathogenic process. Fig. 3 shows how, after almost a century of studies on this disease, Sarria et al. (2008) agreed with Reinking's 1928 report, who stated that Phytophthora sp. is the causal agent of this disease; nevertheless, it is important to emphasize that this genus is the only one to have been explicitly discarded by Quillec (1983). There are also contradictions between the findings; for example, Ploetz (2007a) reported Thielaviopsis paradoxa as a possible casual agent but later discarded this idea in the same year (Ploetz, 2007b), even suggesting that this disease does not have an abiotic origin. Interestingly, with the exception of viruses, viroids, phytoplasma (Dollet, 1991, 1992; Dollet et al., 1994) and nematodes (Guevara and Nieto 1999), almost all of the taxonomic groups of pathogenic microorganisms have been associated in one form or another with the pathogenesis of this disease (Franqueville, 2003) (Fig. 4). Specifically, in regards to casual agents, the following have been implicated: Erwinia sp. for bacteria (Quillec et al., 1984; Allen et al., 1995); Thielaviopsis and Fusarium for fungi (Vargas, 1992; Nieto, 1996; Sánchez, 1990; Gómez et al., 2000); and Pythium and Phytophthora for Oomycete (Quillec et al., 1984; Nieto, 1996; Sánchez et al., 1999; Sarria et al., 2008).

Abiotic aetiology

In the abiotic debate, the majority of authors have used the approach that nutritional factors have an effect on the increase or decrease of this disease. However, there are exceptions from authors such as Pacheco et al. (1985), Gómez (1995) and Van Slobbe, (1996), who indicated that the incidence of this disease is independent of the nutritional state of the soil or of the plant. Notably, at the foliar level, the research results have indicated that the disease develops under conditions of high levels of the macroelements nitrogen, calcium, and magnesium and the microelement iron, and with deficiencies of the macroelements phosphorus and potassium in conjunction with the microelements zinc, copper, iron, and manganese. In regards to the soil values, it has only been reported that a general deficiency of nutrients is correlated with a higher incidence of the disease. For the other physicochemical properties of the soil, the findings agree on the idea that all of the variables associated with drainage problems, including porosity, water conductivity, clay content, and compaction, facilitate the development of BR; likewise, the concentration of exchangeable aluminum and pH are variables that are highly correlated with this disease (Fig. 5, Tab. 1). All of these findings led to the development of the first disease management programs in Colombia (Munévar et al., 2001).

In order to evaluate the influence of humidity on the development of epidemics, Martínez (2010) reported that the disease has been more severe in regions with high precipitation, where the dry season is not well-defined, such as in the WZ or the MMRV zone. This author noted that one or two weeks without precipitation results in a reduction in the number of lesions in the first stages of the disease, which shows that there is a relationship between precipitation and the advance of BR; however, this assertion is not supported by any particular analysis. On the other hand, Venturieri et al. (2009), in the Pará zone of Brazil, found negative correlations between water balance and incidence of the disease when analyzing the moisture parameters with the use of geographic information systems. When the results from the biotic and abiotic approaches are compared, the first shows a larger number of inconsistencies than the second. This is the reason why opportune management based on agronomic and cultivation practices, including drainage management and improvement of the soil fertility, has been the only method that has demonstrated adequate control, as has been reported for the EPZ in Colombia (Munévar et al., 2001; Fedepalma, 2008).

Agroecological factors, such as a reduction in inoculation through the eradication of diseased palms and the presence of vectors of the Orthoptera order, have only been the object of systematic study (Gómez, 1995; Franqueville, 2003; Torres et al., 2008a, 2008b; Martínez et al., 2009).

Genetic resistance

Advances have been slow for producing material in palm genetic breeding programs; since no protocols exist for the infection of the disease, breeders cannot clearly identify resistant genotypes. Furthermore, in the cases that have shown a possible resistance response, it could have been the result of disease escape (Louise et al., 2007; Chinchilla et al., 2007). However, despite these disadvantages, the hybrid material Elaeis oleifera H.B.K. × E. guineensis Jacq. has been reported to be resistant (Amblard et al., 2004; Louise, et al., 2007; Zambrano and Amblard, 2007; Navia et al., 2014), as have seeds with parental sources from material of the Ekona region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Chinchilla et al., 2007). These resistant materials are being planted in the most affected zones, WZ and MMRV, with positive results to date. Another interesting methodology was reported by Navia et al. (2014), wherein they used the epidemiological approach to select for resistant materials. They calculated the disease progress rate (r) for different genetic materials and defined the resistance based on this value. However, possible disease escape cannot be ruled out.

Final considerations

This framework of inconsistencies and reformulations could be caused by the failure of the classic phytopathological model in answering the aetiological question, resulting in divergent approaches. Furthermore, the debate has been centered on the circumstances of the disease rather than on the analysis of experimental information.

Another factor revealed in this analysis was the little coordinated work of the research groups, within and between the institutions that decided to conduct studies on this disease. There are plantations that, due to their size, can support research infrastructure and, as a management strategy, have decided to conduct their own research, leading to a high number of studies on the disease, generating redundant studies and contradicting results, in short, disarticulation between the research groups. Producer associations exert pressure on research institutes because of the lack of convincing short-term results and demand changes in research priorities. Research processes for this pathosystem require years to obtain results and are halted under this situation. As a result, the logic of the studies is based on fears of imminent losses rather than on technical scientific discussion.

BR is a disease that differs in many aspects from the more well-known common diseases, including the group of diseases considered by forest pathologist as declines (Manion, 1991; Chinchilla, 2011, personal communication) that has characteristics that vary from those of BR, mainly in terms of the temporal and spatial speed of propagation (Manion, 1991; Ostry et al., 2011). However, it is plausible that a study on BR could be focused on a complex analysis scheme as proposed by Wallace (1978) and Ostry et al. (2011), who agreed with Franklin et al. (1987), and Hyink and Zedaker (1987) that this type of disease has both pathological and ecological problems and that, in order to establish diagnostic methods, studies must be carried out with a synoptic approach with multiple regression equations. Nevertheless, Wallace (1978) recommended that, in order to decide whether or not to consider determinant factors of the disease, researchers must select the more probable; in this sense, there has been a return to the report by Sinclair (1967) and Ostry et al. (2011), who summarized declines into three groups: predisposing factors, inciting factors, and contributing factors, which can be used as a study scheme for future research on BR.

Finally, as with decline diseases, it is clear that it is not necessary to create a group of different diseases for their classification and that the concept of a disease triangle as proposed by Ostry et al. (2011) and Scholthof (2007) is sufficient for explaining any pathogenic process; therefore, and by way of summary, considering that the cause and effect relationship between the elements of the triangle of the disease are not being fully quantified or validated and a comprehensive view of the problem is not being undertaken, the aetiology of this disease will not be fully understood, culminating in the consequences already seen in the devastated regions.

Literature cited

Acevedo A., N.J., P. Buriticá C., J.A. García N., and N. Gálvis D. 2000. Valoración económica de las pérdidas en aceite generadas por la pudrición de cogollo en los Llanos Orientales de Colombia. Palmas 21, 53-62. [ Links ]

Acosta, A. and F. Munévar. 2003. Bud rot in oil palm plantations: link to soil physical properties and nutrient status. Better Crops Int. 17, 22-25. [ Links ]

Aldana de la Torre, R.C., J.A. Aldana de la Torre, and O.M. Moya. 2010. Biología, hábitos y manejo de Rhynchophorus palmarum L. (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Tech. Bull. 23 Cenipalma, Bogota. [ Links ]

Allen, W., A. Paulus, S. Van Gundy, T.R. Swinburne, M. Ollagnier, and J.L. Renard. 1995. Report on the mission to Ecuador. palmeras del Ecuador-Palmoriente. 13th-20th February 1995. Document Cirad-Cp, Montpellier, France. [ Links ]

Amblard, P., N. Billotte, B. Cochard, T. Durand-Gasselin, J.C. Jacquemard, C. Louise, B. Nouy, and F. Potier. 2004. El mejoramiento de la palma de aceite Elaeis guineensis y Elaeis oleifera por el Cirad-CP. Palmas 25(Special Issue II), 306-310. [ Links ]

Benítez, E. 2015. Epidemiología de la pudrición del cogollo de la palma de aceite. PhD thesis. Faculty of Agricultural Sciences, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogota. [ Links ]

Bergamin Filho, A., L. Amorim, F.F. Laranjeira, R.D. Berger, and B. Hau. 1998. Análise temporal do amarelecimento fatal do dendezeiro como ferramenta para elucider sua etiología. Fitopatol. Bras. 23, 391-396. [ Links ]

Breure, C.J. and F.X. Soebagjo. 1991. Factores relacionados con la incidencia del arco defoliado en la palma de aceite (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) y su efecto sobre el crecimiento y la producción. Palmas 12, 47-58. [ Links ]

Chinchilla, C. and N. Durán. 1998. Manejo de problemas fitosanitarios en palma de aceite: una perspectiva agronómica. Palmas 19(Special Issue), 242-256. [ Links ]

Chinchilla-López, C.M. and N. Durán. 1999. Nature and management of spear rot-like problems in oil palm: a case study in Costa Rica. pp. 97-126. In: Proc. 1999 PORIM Int. Palm Oil Cong.: Emerging Technologies and Opportunities in the Next Millennium (Agriculture). Kuala Lumpur. [ Links ]

Chinchilla, C., A. Alvarado, H. Albertazzi, and R. Torres. 2007. Tolerancia y resistencia a las pudriciones del cogollo en fuentes de diferente origen de Elaeis guineensis. Palmas 28(Special Issue I), 273-284. [ Links ]

Corredor R., A., G. Martínez L., and A. Silva C. 2008. Problemática de la pudrición del cogollo en Tumaco e instrumentos para su manejo y la renovación del cultivo. Palmas 29, 11-16. [ Links ]

Cristancho R., J.A., C.E. Castilla C., M. Rojas M., F. Munévar M., and J.H. Silva Ch. 2007. Relación entre la saturación de Al, Mg, K y la tasa de crecimiento de la pudrición de cogollo de la palma de aceite en la Zona Oriental colombiana. Palmas 28, 25-35. [ Links ]

De Rojas Peña, E. and E. Ruiz. 1972. Factores predisponentes a la pudrición de cogollo en la palma africana (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) en turbo, Colombia. IGAC, Bogota. [ Links ]

Dollet, M. 1991. Etiología de la pudrición de cogollo. Investigaciones virológicas conducidas por el IRHO. Palmas 12, 33-37. [ Links ]

Dollet, M. 1992. Strategies used in etiological research on coconut and oil palm diseases of unknown origin. pp. 95-114. In: Maramorosh, K. (ed.). Plant diseases of viral, viroid, mycoplasma and uncertain etiology. Oxford & IBH Pub. Co. Pvt., Nueva Deli. [ Links ]

Dollet, M., L. Mazzolini, and V. Bernard. 1994. Research on viroid-like molecules in oil palm. Coconut improvement. pp. 62-65. In: Foale, M.A. and P.W. Lynch (ed.). Coconut improvement in the South Pacific: Proceedings of a workshop in Taveuni, Fiji Islands. Proc. 53. ACIAR, Canberra. [ Links ]

Fedepalma. 2007. Enfermedades en palma de aceite: un reto a la sostenibilidad de la agroindustria. Palmas 28, 5-8. [ Links ]

Fedepalma. 2008. Acercamiento científico a la solución del problema de la pudrición del cogollo de la palma de aceite. Palmas 29, 5-6. [ Links ]

Fedepalma. 2014a. Avanza consolidación de franja sanitaria para contener la pudrición del cogollo. In: http://web.fedepalma.org/node/699; consulted: November, 2014. [ Links ]

Fedepalma. 2014b. Palmeros unidos, unión de voluntades para enfrentar la PC. In: http://palmaldia.org/xii-reunion-tecnica/consuelo; consulted: November, 2014. [ Links ]

Franklin, J.F., H.H. Shugart, and M.E. Harmon. 1987. Tree death as an ecological process. BioScience 37, 550-556. Doi: 10.2307/1310665 [ Links ]

Franqueville, H. 2003. Oil palm bud rot in Latin America. Exp. Agric. 39, 225-240. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0014479703001315 [ Links ]

Gómez C., P.L. 1995. Estado actual de la investigación sobre pudrición de cogollo. Palmas 16, 9-23. [ Links ]

Gómez, P., L. Ayala, and F. Munévar. 2000. Characteristics and management of bud rot, a disease of oil palm. pp. 545-553. In: Pushparajah, E. (ed.). Plantation tree crops in the new millennium: the way ahead. Vol. 1. The Incorporated Society of Planters, Kuala Lumpur. [ Links ]

Guevara Á., L.A. and L.E. Nieto P. 1999. Nematodos asociados con palmas de aceite (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) afectadas con pudrición de cogollo. Palmas 20, 93-99. [ Links ]

Hartley, C.W.S. 1965. Some notes on the oil palm in Latin America. Oléagineux 20, 359-363. [ Links ]

Hyink, D.M. and S.M. Zedaker. 1987. Stand dynamics and the evaluation of forest decline. Tree Physiol. 3, 17-26. Doi: 10.1093/treephys/3.1.17 [ Links ]

Hurtado C., R., V. Rincón R., and L.C. Martínez. 2009. Análisis exploratorio de las capturas de Rhynchophorus palmarum L. (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) en lotes afectados por pudrición del cogollo en la Zona Occidental palmera colombiana. Palmas 30, 36-50. [ Links ]

Kraul, C. 2010. Disease lays waste to Colombia oil palms. In: Los Angeles Times, http://articles.latimes.com/2010/apr/07/world/la-fg-colombia-palms8-2010apr08; consulted: November, 2014. [ Links ]

Louise, C., P. Amblard, H. Franqueville, D. Benavides, and C. Gallardo. 2007. Investigaciones dirigidas por el Cirad sobre las enfermedades del complejo pudrición del cogollo en la palma aceitera en Latinoamérica. Palmas 28(Special Issue I), 345-362. [ Links ]

Manion, P.D. 1991. Tree disease concepts. 2nd ed. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. [ Links ]

Martínez, G., N.A. Arias, G.A. Sarria, G.A. Torres, F. Varón, C. Noreña, S. Salcedo, H. Aya, J.G. Ariza, R. Aldana, L.C. Martínez, O. Moya, and C.A. Burgos. 2009. Manejo Integrado de la pudrición del cogollo (PC) de la palma de aceite. Fedepalma; Cenipalma; Sena, SAC, Bogota. [ Links ]

Martínez L., G. 2010. Pudrición del cogollo, marchitez sorpresiva, anillo rojo y marchitez letal en la palma de aceite en América. Palmas 31, 43-53. [ Links ]

Martínez, G., G.A. Sarria, G.A. Torres, F. Varón, A. Drenth, and D.I. Guest. 2014. Nuevos hallazgos sobre la pudrición del cogollo de la palma de aceite en Colombia: biología, detección y estrategias de manejo. Palmas 35, 11-17. [ Links ]

Montes, L. and E. Ruiz. 2014. Eficacia y costo del trampeo para capturar Rhynchophorus palmarum (L.) usando caña de azúcar y melaza aislada. Palmas 35, 33-40. [ Links ]

Munévar M., F., A. Acosta G., and P.L. Gómez C. 2001. Factores edáficos asociados con la pudrición del cogollo de la palma de aceite en Colombia. Palmas 22, 9-19. [ Links ]

Navia, E.A., R.A. Ávila, E.E. Daza, E.F. Restrepo, and H.M. Romero. 2014. Assessment of tolerance to bud rot in oil palm under field conditions. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 140, 711-720. Doi: 10.1007/s10658-014-0491-9 [ Links ]

Nieto P., L.E. 1996. Síntomas e identificación del agente causal del complejo pudrición de cogollo de la palma de aceite, Elaeis guineensis Jacq. Palmas 17, 57-60. [ Links ]

NOAA, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2014. Changes to the Oceanic Niño Index (ONI). In: National Weather Service, http://www.cpc.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/ensostuff/ensoyears.shtml; consulted: November, 2014. [ Links ]

Ostry, M.E., R.C. Venette, and J. Juzwik. 2011. Decline as a disease category: is it helpful? Phytopathology 101, 404-409. Doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-06-10-0153 [ Links ]

Pacheco, A.R., B. Tailliez, R.L. Rocha de Souza, and E.J. De Lima. 1985. Les déficiences minérales du palmier à huile (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) dans la région de Belém (Parà, Brésil). Oléagineux 40, 295-309. [ Links ]

Ploetz, R.C. 2007a. Manejo de enfermedades en cultivos perennes tropicales. Palmas 28(Special Issue I), 326-338. [ Links ]

Ploetz, R. 2007b. Diseases of tropical perennial crops: challenging problems in diverse environments. Plant Dis. 91, 644-663.Doi: 10.1094/PDIS-91-6-0644 [ Links ]

Quillec, G. 1983. Etude de la pourriture du coeur de Shushufindi (Equateur). Institut de Recherches pour les Huileset Oléagineux (IRHO), Paris. [ Links ]

Quillec, G., J.-L. Renardand, and H. Guesquière. 1984. Le Phytophthora heveae du cocotier: son rôle dans la pourriture du coeur et dans la chute des noix. Oléagineux 34, 477-485. [ Links ]

Quintero R., J.L. 2010. Dinámica de captura de adultos de Rhynchophorus palmarum L. (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) en la red de monitoreo de la Zona Occidental. Palmas 31, 17-27. [ Links ]

Renard, J.L. and G. Quillec. 1984. Enfermedades destructoras de la palma africana en el África y Suramérica. Palmas 6, 9-16. [ Links ]

Rodrigues, T.E., I. de J.M. Viegas, D.R. Trindade, H.M. Martins, and R. Cordeiro. 2000. Influência das propriedades físicas do solo na ocorrência do amarelecimento fatal do dendezeiro. Fitopatol. Bras. 25, 350-351. [ Links ]

Sarria, G.A., G.A. Torres, H.A. Aya, J.G. Ariza, J. Rodríguez, D.C. Vélez, F. Varón, and G. Martínez. 2008. Phytophthora sp. es el responsable de las lesiones iniciales de la pudrición de cogollo (PC) de la palma de aceite en Colombia. Palmas 29(Special Issue), 31-41. [ Links ]

Sánchez P., A. 1990. Enfermedades de la palma de aceite en América Latina. Palmas 11, 5-38. [ Links ]

Sánchez, N.J., L. Ayala S., E. Álvarez, and P.L. Gómez C. 1999. Patogenicidad, identificación y caracterización molecular de Phytophthora spp. en palma de aceite. Ceniavances 60, 1-4. [ Links ]

Scholthof, K.B. 2007. The disease triangle: pathogens, the environment and society. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5, 152-156.Doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1596 [ Links ]

Silva C., A. and G. Martínez L. 2009. Plan nacional de manejo de la pudrición del cogollo Fedepalma - Cenipalma. Palmas 30, 97-121. [ Links ]

Silveira, R., A. Vieiga, E. Ramos, and J. Parente. 2001. Evolução da sintomatología do amarelecimento fatal a adubações com omissão de macro e micronutientes. Denpasa, Belém, Brazil. [ Links ]

Sinclair, W.A. 1967. Decline of hardwoods: possible causes. Proc. Int. Shade Tree Conf. 42, 17-32. [ Links ]

Torres, G.A., G.A. Sarria, F. Varón, and G. Martínez. 2008a. Evidencias circunstanciales de la asociación de especies de la familia Tettigoniidae con el desarrollo de lesiones iniciales de la pudrición del cogollo de la palma de aceite. Palmas 29(Special Issue), 53-61. [ Links ]

Torres, G.A., G.A. Sarria, S. Salcedo, F. Varón, H.A. Aya, J.G. Ariza, L. Morales, and G. Martínez. 2008b. Opciones de manejo de la pudrición del cogollo (PC) de la palma de aceite en áreas de baja incidencia de la enfermedad. Palmas 29(Special Issue), 63-72. [ Links ]

Tovar, J. 2014. Comportamiento de la enfermedad pudrición del cogollo (PC) de la palma de aceite en las plantaciones ubicadas en los Llanos Orientales colombianos. Coordinación de Manejo Sanitario Núcleos Palmeros Zona Oriental, Fedepalma, Bogota. [ Links ]

Van der Lande, H.L. 1993. Studies on the epidemiology of spear rot in oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) in Suriname. Landbouw Universiteit, Wageningen, The Netherlands. [ Links ]

Van der Lande, H.L. and J.C. Zadocks. 1999. Spatial patterns of spear rot in oil palm plantations in Surinam. Plant Pathol. 48, 189-201.Doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3059.1999.00331.x [ Links ]

Van Hall, C.J.J. 1921. Diseases and pests of cultivated plants in the Dutch East Indies in 1920. Med. van het Inst. voor Plant. 46. 50 p. In: Imperial Bureau of Mycology. 1922. Rev. Appl. Mycol. 1, 18-20. [ Links ]

Van Slobbe, W.G. 1996. Oil palm estate Denpasa and other oil palm plantings in Parana. II. Second Interim Report of Short-Term Consultancy on the Progress of fatal Yellowing Disease (Amarelecimento Fatal - AF). Belém, Brazil. [ Links ]

Vargas, M. 1992. Fusarium solani: agente causal del complejo pudrición de cogollo? Palmas 13, 59-67. [ Links ]

Venturieri, A., W.R. Fernandes, A.J. Boari and M.A. Vasconcelos. 2009. Relação entre ocorrência do amarelecimento fatal do dendezeiro (Elaeis guineensis jacq.) e variáveis ambientais no estado do Pará. pp. 523-530. In: Anais XIV Simpósio Brasileiro de Sensoriamento Remoto. INPE, Natal, Brazil. [ Links ]

Viégas, I.J.M., J.J. Furlan, D.A.C. Frazão, and M.M.F. Batista. 2000. Influência do micronutriente ferro naocorrência do amarelecimento fatal do dendezeiro. Tech. Bull.32 Embrapa Amazônia Oriental, Belém, Brazil. [ Links ]

Villanueva G., A. 1988. Apreciaciones acerca del seminario internacional sobre identificaciones y control de organismos y/o factores causantes del síndrome conocido como spearrot en palma de aceite. Palmas 9, 37-46. [ Links ]

Wallace, H.R. 1978. The diagnosis of plant diseases of complex etiology. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 16, 379-402. Doi: 10.1146/annurev.py.16.090178.002115 [ Links ]

Zambrano R., J.E. and P. Amblard. 2007. Resultados de los primeros ensayos del cultivo de híbrido interespecífico de Elaeis oleifera x Elaeis guineensis en el piedemonte llanero colombiano (Hacienda La Cabaña S.A.). Palmas 28(Special Issue I), 234-240. [ Links ]