Introduction

In the Tierradentro region, the Yaquiva reservation has compiled its life guidelines, proposals and budgets into a single document called the "Life Plan". This plan can be defined as a way to organize the future of a community, taking into account advances in terms of territory, economy, rights, education and culture, while exercising autonomy (Huila, 2017). An integral life plan starts with the history of a town, values the awareness and socialization of each community's knowledge, analyzes its problems and needs, and enables the creation of pedagogical and methodological proposals that dynamize life projects (ONIC, 1999). These documents generally include a diagnosis of the fundamental problems and needs of communities, as well as a set of possible solutions and programs to guide the development of public policies in accordance with the indigenous people's worldview and history. Therefore, each town designs its own life plan according to its ethnic and cultural characteristics (Resguardo Indígena de Yaquivá, 1999).

The expression "Life Plan" can be interpreted with the way each ethnic group puts it into sociocultural and historical context and the level of "acculturation" the ethnic group has. Therefore, the ethnic and cultural diversity of Colombia is reflected in the multiplicity of ways to view a plan. For this reason, it is not possible to have a unified concept of what a life plan is, how it should be done, and who should do it. However, life plans have been defined in two complementary ways: as a tool for cultural, social, political and economic affirmation of indigenous peoples and, on the other hand, as a strategy of negotiation and agreement with society in the construction of a multiethnic and pluricultural nation (ONIC, 1999). Consequently, a life plan is also a possibility for a community to recreate its culture through a process of permanent self-diagnosis, which must be set in its own reality: yesterday, today and tomorrow (Franco, 2010).

A life plan is a cultural expression and a negotiation strategy to establish relationship principles with factors outside indigenous communities. The real reasons for a life plan are fundamentally linked to the way in which non-indigenous communities wish to relate. Moreover, they are determined by historical moments that, in almost all indigenous peoples and nations, make a big difference with the remaining population of Colombia (Monje, 2014). However, all these efforts to incorporate indigenous people into Colombian society, especially in the economic and political systems, have had negative consequences for indigenous cultures and organizations.

In spite of this, one of the subjects that indigenous communities have insisted on the most has been education, especially the teaching of native languages as an ancestral and cultural heritage. According to the Regional Indigenous Council of Cauca (CRIC for its acronym in Spanish), memory teaches and shows us the way; we all resist aggression that mistreats us, but everyone respects diversity and differences, so the future depends on a set of collective consciences and autonomies that are in balance and harmony with all beings (CRIC, 2004).

On the other hand, a life plan is a response to the sustainability of an indigenous process, which is based on a permanent construction of social and natural spaces. It should also take place in fair environments for the parties immersed in it, with respect to their social and cultural constructions. This respect should not only come from non-indigenous or government entities, but also from themselves to ensure that what they build day by day is reflected in their reality. Additionally, the basis for this respect should be their own history, with an autonomous presence in their territories, in order to survive, sustain, recover and highlight their culture, retrieve their ancestral work and resist modernization (Monje, 2014). Therefore, these communities try to function without industry and capitalism, which paralyze them, using models of self-organization, restoration of relationships, revaluation of food and agricultural functions, readjustment to natural cycles and de-commodification of processes and values (Naredo, 2006).

Although indigenous communities, and especially the Yaquivá reservation, have had a life plan throughout history that has allowed them to exist as important communities for the nation, within the Colombian ethnographic literature, there are no records that account for the existence of systematized life plans from the agroecological approach. Therefore, the objective of this study was to analyze the life plan for the Yaquivá reservation from the four dimensions of agroecological research: distributive, structural, dialectic and spiritual.

Materials and methods

Location

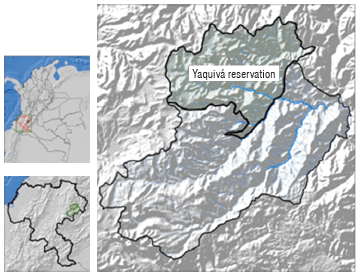

The Yaquivá reservation is located to the east of the central mountain range, in the municipality of Inza, province of Cauca, Colombia (Fig. 1). It has an approximate population of 3,900 inhabitants and a total area of 16,184 ha, at an altitude between 1,600 and 4,000 m a.s.l. in a paramo area. The precipitation and average annual temperature are between 1,000 and 2,000 mm and 18°C, respectively. In order to bring institutions and academia closer to rural and indigenous communities, 2008 participatory research has been carried out between the Universidad Nacional de Colombia and the indigenous community of the Yaquivá reservation. In this study, Participatory Action Research (PAR) was used as the methodology, and participant observation, discussion groups, participatory diagnoses, surveys and interviews, dialogical dialogues (dialogue of knowledge and dialogue of doing), literature review and secondary sources were used as the methodological tools.

Other techniques used to collect the information included meetings, visits, pedagogical tulpas, labor activities and mingas, of both work and thought. The term Tulpa refers to a word derived from the Tul (ancestral Nasa orchard) production system, where training events are held. Minga corresponds to collective efforts to fix roads or aqueducts and build homes, health centers, or schools, in which all the members of the community participate.

Dimensions of agroecological research

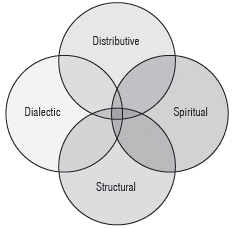

According to Ottmann (2005) and Sevilla (2006, 2009), agroecology is based on three dimensions that develop the study of existing strategies for social and ecological reproductions of agroecosystems. These dimensions propose the rescue of dynamics that, at another time, were based on the recognition, use and creation of diversity. These dimensions act in accordance with natural laws and do not contravene them (Toledo and Barrera-Bassols, 2008). The three dimensions of agroecological research proposed by Ibañez (1996) are: the ecological and technical productive (distributive), the socioeconomic and cultural (structural) and the political (dialectic) dimensions. In addition, this research proposed the spiritual dimension (Fig. 2).

The distributive dimension of agroecological exploration-action moves in a productive space (Sevilla and Ottmann, 2000). In the ecological and technical productive dimension, agroecology aims to learn and promote modes of appropriation of nature that: a) respect mechanisms of self-maintenance, self-regulation and self-repair that every ecosystem possesses independent of societies and human intervention (Toledo, 1985) and b) come from adaptation and integrated coevolution between culture and the environment (Norgaard, 1985; Norgaard and Sikor, 1999). On the other hand, the structural dimension is made up of agroecology as rural development and refers to it as a socioeconomic process for obtaining the optimum level of life allowed by existing resources; it is a productive and participative strategy for obtaining sustainability through forms of collective social action (Sevilla and Ottmann, 2000).

The dialectical dimension, in which participatory action research breaks the subject-object power structure of the scientific methodology (known as "laboratory rebellion"), generates the possibility of change in social actions within performance events, such as "historical analyzers" (Delgado and Gutiérrez, 1995). The socio-political dimension of agroecology or the cultural and political management of natural resources (Cuéllar, 2008) complements the socioeconomic concept of the structural dimension from the perspective of breaking with the conventional scientific and epistemological paradigm. Without this, it is not possible, from the agroecological perspective, to achieve fair environmental, social and economic sustainability in accordance with existing cultural diversity (Sevilla, 2009).

As a consequence of the multiple forms of cultural resistance, certain values were forged, which are incorporated into social memories and which are rescued along with local rural and indigenous knowledge with agroecology. Therefore, the sociopolitical dimension states that, without intervention in the established power structures, it will not be possible to propose alternative integral development strategies. These strategies should truly satisfy this focus and be placed in a new "ecological paradigm" that is built on the basis of contributions from both criticism of the dominant mechanistic model and the emergence of new scientific disciplines (Garrido, 2007).

The last level is the spiritual one; according to Boff (2000), modern culture tends to occupy humans with a giant avalanche of messages and requests. Our being has become contaminated with materialism and dehumanized, with a loss of all transcendence that feeds the spirit. The spirit, in its original sense, from which the word spirituality derives, is in every being that breathes. Therefore, it is in every being that lives, such as human beings, animals and plants. However, Earth and the universe live as bearers of spirit because life comes from them, and they provide all the elements for life and maintain the creative movement.

In this sense, human beings represent a unitary compound of body and spirit. Spirituality is one of the dimensions of humans, that of the spirit. In addition, spirituality motivates inner transformation. It can happen at any age or state or time and in both sexes. Spirituality is that attitude that places life at the center, promoting it against all mechanisms of death. The opposite of spirit is not body, but death and everything that is attached to the system of death, taken in its broad sense of biological death, social death and existential death (failure, humiliation, and oppression) (Mejía, 2011).

Feeding spirituality means cultivating the inner space, from which things are connected and re-connected. This means overcoming stagnant behaviors and living the realities beyond their opaque and sometimes brutal existence, as values, inspirations, and symbols of deeper meanings. A spiritual man/woman always perceives the other side of reality and is capable of capturing the depth that is hidden and the reference of everything with the ultimate reality, which religions call God (Boff, 2000).

Results and discussion

The analysis of the life plan is presented from perspective of the four dimensions: distributive, structural, dialectical (Ibáñez, 1996) and spiritual (Chate, pers. comm.; Mejía, 1999; Boff, 2000). Taking into account these dimensions, the different constitutive elements of the life plan are grouped.

Distributive dimension

The income of most of the population of the Yaquivá reservation comes from the agricultural sector, mainly from the production and commercialization of coffee (Coffea arabica). Two types of production are clearly identified: the first one belongs to the rural economy, characterized by permanent crops such as coffee, sugar cane (Saccharum officinarum) and banana (Musa paradisiaca), with the application of some techniques from the green revolution technological package (for cash crops). In contrast, the second type of production, of indigenous family economy, is carried out for self-consumption, with subsistence crops of produce such as: corn (Zea mays), beans (Phaseolus vulgaris), potatoes (Solanum tuberosum), broad beans (Vicia faba), ulluco (Ullucus tuberosus), onions (Allium cepa), cabbage (Brassica oleracea), and coriander (Coriandrum sativum), among others. This type of production has scarce commercial surpluses, is developed in systems associated with traditional techniques such as slash, burn and rotation of land, and does not use pesticides or fertilizers made with petrochemical synthesis. Additionally, the contribution of labor from family members (mainly female and child labor) and neighbors (Franco, 2010) stands out.

However, in Tierradentro, vegetable crops have decreased in diversity compared to the crops that the Spanish colonizers found (Patiño, 1969). Apparently, this is one of the reasons for the conditions of impoverishment, but at the same time, one of the possible explanations for the persistence of traditional crops. The traditional use and management of Tierradentro's useful plants is the result of the persistence of a traditional agricultural system and the cultural resistance of the Nasa ethnic group in its territory. In addition, under the notion of Kiwe (Nasa term), which means "see, sow and harvest", agricultural activities are central to the conservation and defense of territories: it is the means of life (work) for its inhabitants, which in part assures the survival of the ethnic group (Sanabria, 2001).

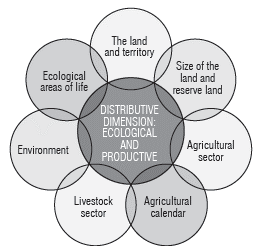

The persistence of vegetables under the traditional agricultural system is based on a subsistence economy in the ecological and socio-cultural context of the Nasa territory (Sanabria, 2001). However, the persistence of different Andean edible crops and the ones adapted from other regions is due to the political process of indigenous autonomy and the resistance and socioeconomic marginalization of the Nasa territory (Sanabria, 2001). On the other hand, the traditional production practices carried out on the reservation guarantee the continuity of the productive initiatives developed in the Jiisa Fxiw (Nasa term meaning seed of knowledge) agroecological school over time. Acevedo (2015) found that the systems of traditional agriculture showed the highest values of multifunctionality and the best performance in terms of environmental and productive sustainability, while the farmers and semi-annual monocultures showed a lower degree of multifunctionality and sustainability. The ability of farmers to perform multiple tasks in their farm systems is a strategy of resistance for overcoming adversities that put the productivity of the systems at risk. Finally, the ecological and productive aspects are grouped as: the land and the territory, size of the land and reserve lands, agricultural sector, agricultural calendar, livestock sector, environment, and ecological life zones (Fig. 3).

Structural dimension

For the Nasa people and the Yaquivá community, the conservation of their culture and cosmogony is of great importance, which is reflected not only in the life plan that was created in 1999, but also in the interest shown in developing productive projects that improve socioeconomic conditions and the level and quality of life for its commoners. Therefore, the Yaquivá reservation is integrating the Nasa culture into an ethno-education and production strategy in the Community Education Project (PEC for its acronym in Spanish) of the Jiisa Fxiw agroecological school, which seeks to strengthen sovereignty, dignity and food and nutritional autonomy. Education for ethnic groups is a public service and is based on a commitment to collective elaboration where different members of the community exchange knowledge and experiences in order to maintain and recreate processes that development their cultures. This is achieved through real policies of bilingual and intercultural education in accordance with their language, traditions and indigenous privileges (Mineducation, 2009; Franco and Chate, 2015).

Therefore, since its inception, the CRIC has created strategies for education that take indigenous culture into account, which is how the alternatives of bilingual education and processes of ethno-education were born (CRIC, 2004), as stated in article 68 of the National Political Constitution of 1991. In addition, with the firm purpose of advancing the guidelines of the life plan and dynamizing its policies through the PEC, teachers meet with students, parents and traditional authorities in order to assume the organization of new technologies to improve the educational quality and strengthen agroecological production for the educational institution Jiisa Fxiw and the reservation (Franco, 2010).

However, the construction processes of the PEC in the Jiisa Fxiw school, as well as the life plan, have faced problems such as: a lack of infrastructure and resources, difficulties of appropriation of the territory, natural disasters, and problems of exclusion and violence in the region. This project has reached the productive and political areas of the community and is part of all the dynamics of participatory governance of the reservation (Franco, 2010).

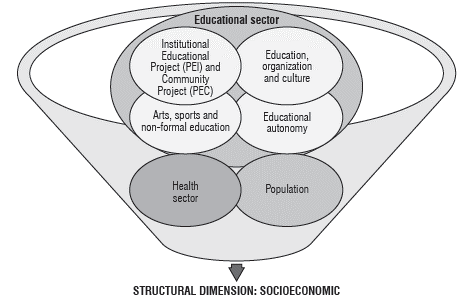

Finally, the aspects related to the socioeconomic part were grouped as: population, health and education sectors (education, organization and culture, the Institutional Educational Project (PEI for its acronym in Spanish), the PEC, educational autonomy, arts, sports and non-formal education (Fig. 4)).

Dialectical dimension

The political organization is based on Cabildo, a legal figure implanted by the Spanish crown, supported by the laws of the liberator Simon Bolivar and ratified in Law 89 of 1890. The organizational dynamics of indigenous communities is a major factor in long-term, proactive and constructive tasks; they have a great capacity for action, reaction and adaptation, which have survived millennia, even after suffering attacks throughout history, an indication that they will continue towards the achievement of many objectives and accomplishments.

As for the organization, there have been substantial advances that have led to improvements in living conditions, such as belonging to an association of Cabildos, setting up their own working committees, establishing some parameters of action that guarantee peaceful coexistence with autonomy and freedom and achieving progress in the solution of unsatisfied basic needs for the community. On the other hand, from the point of view of identity, specifying the origin of the inhabitants of the reservation is not difficult since the cultural heritage is mostly preserved, such as the ancestral language (Nasa Yuwe), governance, spirituality, food, economy, folklore and territory.

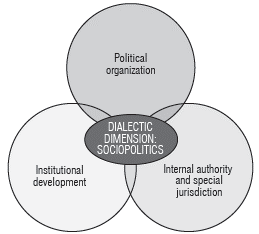

If there is self-governance, it is because the territory is constituted in a reservation with autonomy, where different activities of an indigenous council are performed; the commoners, with the minimum amount of land, have autochthonous technology learned through oral tradition from elders. Hence, its history is based on ancestry (Resguardo Indígena de Yaquivá, 1999). Finally, the aspects related to the sociopolitical part were grouped as follows: political organization (the governor, mayors, marshals, commissaries, treasurer, secretary, and councils), internal authority and special jurisdiction and institutional development (Fig. 5).

Spiritual dimension from the Nasa cosmovision

When talking about the origin of the Nasa world, Chate (pers. comm.) stated that, at the beginning, everything was dark and lonely; there were only two superior beings that moved from one place to another through the universe. One of them was called Uma and the other was named Tay; male and female cosmic entities, these two spiritual beings were very sad because they felt alone, so they agreed to procreate and their children were scattered throughout the universe. Among their children, Kiwe (Earth) was born and became a very beautiful young woman. Sek (sun), a handsome young man, started to court her, but he had difficulty approaching her since she was very hurt by his high temperature. Uma and Tay agreed that the young Sek could only see their daughter and get close to her from a certain distance. This way, life was possible on Kiwe (Earth), and Kiwe and Sek shared their lives in the universe. This union produced an innumerable diversity of offspring, to the point that everything became chaotic as Kiwe's children started to fight and caused many difficulties. Uma and Tay were forced to intervene and establish rules of coexistence, but, since the universe was so big, and they could not be vigilant, they established some delegates who were in charge of ensuring the balance and harmony of everyone in the Kiwe family.

These delegates were located at strategic places, such as rivers, lagoons, swamps, hills, springs, mountains and stubbles; they penalized Kiwe's children, especially humans, when they broke the rules of balance and harmony. These delegates are the spiritual beings who are in charge of maintaining the equilibrium with everyone. The person in charge of establishing this communication between the beings of the cosmos and the Nasa or humans is the The Wala (a wise member of the Nasa community who has been selected by the beings of the cosmos to do this task). Thus, the The Wala has specific functions, such as being the conciliator between the Nasa and the sacred cosmic beings. There is a language that has been established between the The Wala and the spiritual beings that only they know; this communication is done mainly through vibrations in the body, visions, and signs of nature that the wise man interprets while being very concentrated.

Additionally, from the point ofview of Nasa spirituality and feasts and rituals, every 1st of November, the Tafxi (ritual of the souls) is performed at the family and community levels, which consists of making an offering to people who have passed away and embarked on the long journey. Currently, other rituals, such as Cxapuc (appreciation for Mother Earth) and Sakhelu (ritual of seeds) are being recovered. On the other hand, from the organizational and political point of view, the ritual of territorial renewal of the command insignia of the council directors has taken place. From the socio-economic point ofview, renewal or harmonization of diversified autochthonous crops, the Nasa tul, the seeding of the navel, the dwelling and the body are carried out. The cleaning of the body is done when women are menstruating, at the time of delivering a baby and after a funeral.

In view of multiple religions existing on the reservation, it is necessary to look for strategies of agreement and understanding towards Nasa spirituality.

On the other hand, the organization based on PEC and Tul converge in an ethnoecological proposal that was developed through participatory talks with professionals, technicians, teachers, students, the community in general, the The Wala and elders, who are fundamental to rescuing ancestral knowledge (Franco, 2010), which is very necessary to overcoming difficulties. From the local perspective, and from the impulse of the Tul, which is defined as those tissues of the soil with food plants, bits of mountain that are already planted to eat, an environmental and cultural tissue is reconstructed, in which the The Wala (traditional doctors) and elders direct what to sow, how to sow and how much to sow, as exercises of autonomy, territoriality, spirituality, culture and unity.

The Tul is considered the expression of the capacity of domestication and technological adaptation under the diverse Andean agro-ecological conditions. In the Tul, the steps or meeting places of basins and sub-basins constituted points of Andean economic dynamism for a living local territory. These points of dynamization, which are more than 500 years old and have withstood the attack of production models of the green revolution, continue to offer their benefits to the communities; at these points, systems of reciprocity and exchange of products and food continue to be dynamic and intense. This testimony of historical permanence constitutes a reliable indicator of its sustain-ability (Vásquez, 2004).

Despite western sociocultural attacks, the Nasa have skillfully preserved much of the cultural heritage, such as: thought through language, spirituality manifested through rituals, traditional medicine, minga, a collective form of work, and the Tul as part of autonomy, dignity and food sovereignty. Therefore, the technology transfers and agro-ecological practices are designed to make the sovereignty, autonomy and food dignity of the Yaquivá community possible. For food autonomy, the residents of the reservation state that "he who knows what he sows decides what he eats"; in addition, they say that "food is produced to eat first and, if there is something left over, it can be used to barter or to sell". Food dignity is understood as "mutual respect between all beings to produce food in harmony", with a more spiritual concept (Chate, pers. comm.).

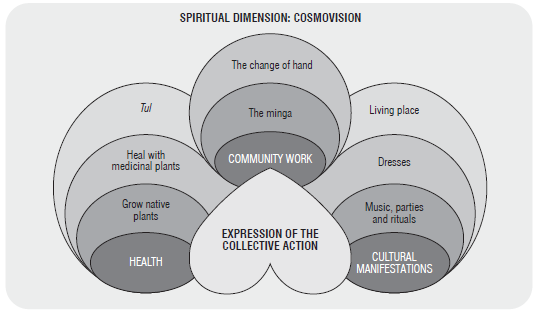

The following activities are grouped in Figure 6: health (grow native plants, heal with medicinal plants and Tul), cultural manifestations (living place, dresses, music, parties and rituals), and community work, i.e. minga and change of hand. Change of hand refers to the work dynamics in which members of the community work from farm to farm in order to accomplish certain goals that could not be achieved by working individually.

Conclusions

The life plan for the indigenous reservation of Yaquivá has a high level of appropriation and represents a novel advance in both the theoretical and practical aspects. By its nature, it is understandable that the formulation of the life plan is an exercise in decision-making for collective action. It is based on the orality of their culture and the revitalization of traditions; it is a useful tool for promoting reflection processes within communities for their political, social, cultural, economic and spiritual dynamics in order to reach an acceptable level of formalization and implementation of these dynamics.

Finally, in the analysis of the life plan for the Yaquivá reservation from the agroecology perspective, agreements are gathered on the most appropriate forms of behavior in social relationships and with nature. In this analysis of the life plan of the community, emphasis was placed on the fourth dimension, the "spiritual" one, given the need to resume its contributions within the process of change for purposes that transcend the economic level and that are inserted in welfare. This emphasis intends to collaborate the construction of conceptual and methodological references at the level of other reservations, citizens and the scientific community on apparently evident subjects that are invisible to a culture that believes that the goods of the Earth are infinite.