Introduction

An evaluation of the Millennium Development Goals for Colombia (PNUD, 2015) indicates that, although women participate more at the decision-making levels and have achieved a reduction of inequity gaps in the labor market in the last 20 years, inequity still exists. In 2014, men occupied 77% of the congressional seats in the Republic of Colombia. In the realm of labor, there were salary differences of about 20% between the genders. This situation is possibly associated with the fact that the informal work rate for women is 52%, seven percent higher than for men (PNUD, 2015). Therefore, inequity and inequality are still present domestically.

Rural women have traditionally been in charge of household tasks, which include feeding, cleaning, taking care of and educating children, and taking care of the elderly and sick relatives. Additionally, they have done other activities related to the entire agri-food system, which range from caring for natural resources and animals for household-consumption to seed protection, planting, harvesting, commercialization, preparation, consumption and biological use of food (OSAN Colombia, 2015; Suarez and Del Castillo, 2016). Daily, rural women are in charge of activities that require a lot of time and dedication, without any kind of economic remuneration or, in many cases, without any recognition of their contribution to food and nutrition security (FNS) and to the economic and social development of their country and region (Suarez and Del Castillo, 2016).

Rural women suffer double discrimination: first because they are women and second because they are rural (OSAN Colombia, 2015). Estimating the precise number of rural inhabitants in Colombia and conceptualizing that number is very difficult because the term "rural inhabitant" does not appear in the national census; instead the category "the remainder" population is used (PNUD, 2011). Furthermore, in Colombia, the term "rural inhabitant" is not reflected in agricultural policies and does not appear in the current National Agricultural Census of 2014, wherein they are classified as "Producers of the countryside". Nevertheless, this concept is considered a cultural category and a reference of self-recognition by a large part of the Colombian rural population (Universidad del Rosario, 2016).

In spite of the important work that women do contributing to food and nutrition security, especially in the production and processing of food products, there are currently no formal female organizations in this area according to the Agriculture and Economic Development Secretaries of the municipalities of Sibate, Sopo and Location 20 of Bogota (Sumapaz).

In the organizations that women participate in, they usually do not hold decision-making positions, a situation that could lead to less access to technical assistance, agricultural inputs, technology, land, commercialization chains and credits for rural women (Suarez and Del Castillo, 2016). The National Agricultural and Livestock Census of 2014 indicates that, in spite of the fact that Colombian men and women have the same illiteracy level (12%) and that more women attend schools in rural areas, land and services continue to be handled by men at a greater proportion (DANE, 2014).

This situation, along with a lack of knowledge and/or an underestimation of women's role in communities, goes against local development, food production, local value chain strengthening, equity and FNS. As was pointed out at the International Conference on Nutrition held in Rome in 1992, "women and formally constituted women's food production organizations are often more effective, efficient and essential to improve household food security' (FAO, 1992). It has been shown that, if the role of women is strengthened, and activities that significantly increase their productivity are prioritized, hunger and malnutrition will be reduced and livelihoods will improve. This benefits not only women, but also the entire population (FAO, 2014).

Colombia has a broad normative compendium in relation to gender equity and protection of women's rights, which fosters non-discrimination and elimination of all forms of gender-based violence. This compendium promotes the strengthening and conformation of women's organizations, wage equity and employment quality, support and financing of women's productive projects and/or initiatives and implementation of municipal policies for rural women, among other things (Alcaldía Municipal de Sibaté, 2016; Alcaldía Municipal de Sopó, 2016). However, despite these initiatives, it is necessary to continue strengthening women in order to make their role and organizational strategies more visible in order to reduce poverty and inequity, as well as to contribute to improved health and nutrition of their families and community.

Accordingly, this research used the following concepts as the starting point:

The concept of "the empowerment of women", which has been pursued since the Third World Conference on Women held in Nairobi in 1985, is a process of acknowledgment and extension of the control of women over themselves and their environment, in the personal, social, political, economic and cultural spheres (PADEM, 2004).

The concept of "associative process for work", coined by authors such as (Haeringer et al., 1997), refers to the capacity that social actors have to solve individual and collective problems and needs by working with a principle different from that of the market economy. It is based on solidarity, reciprocity and democratic participation for the development of objectives and rules of internal order, where the big difference between the associative process and companies is the production of goods and services. For companies, the good or service generates the social bond, while for the associative process, the social bond generates the good or service (Maldovan and Dzembrowski, 2009).

Finally, the Observatory of Sovereignty and Food and Nutrition Security of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia (OBSSAN UN) states that FNS is "The right of all people to access the food they need in a timely and permanent manner in adequate quantities and quality for their consumption and biological utilization, guaranteeing them a state of nutrition, health and well-being, which contributes to human development and allows them to be fulfilled and happy" (OBSSAN UN, 2010).

The concept from OBSSAN UN points out that the FNS in Colombia not only depends on food and nutritional factors, but also on environmental, social, economic, political and cultural factors. Aspects such as educational level, distribution of tasks within households, economic autonomy and empowerment of rural women play a fundamental role in the progressive achievement of the human right to food. These aspects also contribute to attaining other human rights and, consequently, the economic and social development of the country. In this context, the present research aimed to characterize the processes of empowerment in rural women's associations as a possible contribution to the FNS of their families and their community.

Materials and methods

This research was based on a qualitative research methodology called "descriptive case" and was developed according to the methodology of Yin (2009). This methodology is defined as empirical research that investigates a contemporary phenomenon in depth within its real context, especially when the limits between the phenomenon and the context are not apparent. This same author pointed out that the descriptive case research tries to describe what happens in a particular case, facing a technically distinctive situation in which there will be many more variables of interest than the observational points (Yin, 2009).

Selection of case studies

The selection of the case studies was performed hand in hand with the Ministry of Agriculture of the Municipality of Sibate, the Secretary of Economic Development of the Municipality of Sopo, and the Nazareth Hospital in the Sumapaz location, who helped contact the leaders of 19 rural organizations in territories that produce and/or process food.

Subsequently, the three organizations with the largest number of female members were selected from these 19 organizations for this research:

The Municipal Association of Rural Users from Sibate (AMUC Sibate)

The Municipal Association of Rural Users from Sopo (AMUC Sopo)

The Rural Producer Network of Life and Peace of Sumapaz.

These cases were selected because of their homogeneity since Sibate, Sopo and Sumapaz are located in Cundina-marca, a province in the Colombian Andean region that is very close to the urban area of Bogota. The studied municipalities have a large rural area, a strong agricultural tradition and vocation, and an economy based on agriculture and livestock, where they grow and process cold weather foods such as vegetables and dairy.

Data collection instrument

An operational gender survey from Emory University and the United Nations Entity for gender equality and the empowerment of women (UN women) was used for the data collection. This survey was previously translated into Spanish, validated and adapted for Colombia by the World Food Program (WFP) and the Universidad Nacional de Colombia for the study: "Evaluation of the effect of marketing interventions for women on economic empowerment and risk of intimate partner violence" (PMA and Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 2016). This instrument was adapted to the research objective and the context of the rural population of the municipalities of Sibate, Sopo and the rural area of Bogota. The final survey was composed of 201 questions, grouped into six chapters, which included questions on demographic characterization, economic income and livelihood, associative process, role in decision-making at the associative and family levels, norms and gender attitudes, financial empowerment and coercion.

Field operational scheme

The data were collected during household visits with women from the selected organizations during the months of July, August and September, 2016. The collected data were then systematized and analyzed.

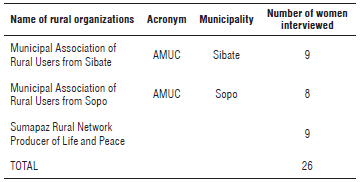

The following table shows the number of women surveyed in each organization (Tab. 1).

Analysis plan

The information obtained in the surveys was classified by food producing and processing organization in order to organize the three case studies. Then, following the methodology of Yin (2009), a consistency matrix between the proposed objective and the obtained information was created, which determined the categories of interest for the analysis and discussion presented in this document.

Results and discussion

First, each of the selected cases and the common socioeconomic characteristics in the three cases were generally described. Then, the processes of empowerment from the associative perspective and the empowerment of the rural women and their relationship with food and nutrition security were analyzed.

Case of the Municipal Association of Rural Users from Sibate - AMUC Sibate

AMUC Sibate is a non-profit, autonomous and independent association with more than 17 years of experience and with a legal organizational structure since 1997. AMUC Sibate is a democratic association; it has a board of directors that is responsible for representing the opinions of its members and making decisions on their behalf (Cámara de Comercio de Bogota, 2015a).

It currently has 16 active members (ten women, six men), whose main activity is the production and commercialization of food such as peas, potatoes, strawberries, carrots, vegetables, blackberries, honey, eggs, curds, and minor species, among others. They also process items such as cheese, curds, desserts, arepas and envueltos, among others. For the last two years, the association has been able to promote and make these products visible in the monthly farmer's markets that are held in the municipality.

Women from the association have been registered for more than a year, and they joined after being summoned by relatives, friends and the municipal government. Motivated by meeting new friends, these women leave their homes in order to get some time for themselves. Currently, two of them are part of the association's Board of Directors. The majority pointed out that they participate by attending meetings and selling their products in the farmer's markets, a situation that makes them feel satisfied with the way in which decisions are made within the association.

Case of the Municipal Association of Rural Users from Sopo - AMUC Sopo

AMUC Sopo is a formally constituted association, registered with the Chamber of Commerce in 2015; however, it has been operating since 1972. It is composed of rural farmers from the municipality in a collective and voluntary manner, under a democratic and non-profit model that promotes cooperation and commitment for their enrollment in productive and agro-industrial projects (Cámara de Comercio de Bogotá, 2015b).

It currently has 21 active members, of which ten are women and eleven are men. Thanks to their resources and support from the Departmental Association of Rural Users (ADUC) and the Mayoralty, they receive technical assistance, plots on loan for crops, and resources on loan, such as tents, tables and transport. Altogether, this helps them participate in the farmer's markets of the municipality on a fortnightly basis, a space where the rural economy is promoted and made visible, from production to the final consumer, with conditions of quality, safety and fair prices.

This is how rural women began to formally join AMUC Sopo two years ago, with ideas such as leaving home, learning more about the management of home gardens, having greater access to technical assistance, obtaining their own economic resources, being self-employed and supporting the household economy and expanding their social circle. This occurred after they were invited by their relatives and friends, the Municipal Agricultural Technical Assistance Unit (UMATA), ADUC and the municipality of Sopo.

In terms of the experience of this organization, only three out of the eight women interviewed have been chosen to occupy a leadership position in this association. One of them currently has the position of auditor. Moreover, when she was asked about how satisfied they felt about the decision-making role in the association's processes, half of the women interviewed said they felt unsatisfied because they did not make decisions within the association, as opposed to the men in the association AMUC Sopo.

Case of the Rural Network Producer of Life and Peace of Sumapaz

The Rural Network Producer of Life and Peace of Sumapaz is an organization of small producers from Nazareth and Betania, two villages of Sumapaz, called the 20th location of Bogota. It is a 100% rural territory that was created by the community after a process of participation and training at three levels of the "Rural School of Managing Leaders in Sovereignty and Food and Nutrition Security". An initiative that was led by the Observatory of Sovereignty and Food and Nutrition Security of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia (OBSSAN UN), whose main objective was to strengthen the social fabric and community empowerment processes as a contribution to food sovereignty and FNS.

The school provided theoretical and practical components, where both teachers and the community had interdisciplinary spaces to learn, debate and build on topics such as planning, participatory management, project formulation and management, the right to food and food sovereignty among others. These topics made possible to strengthen community participation and organization and, as mentioned above, to create the Rural Network of Producer of Life and Peace of Sumapaz. The members of this network have formulated and are implementing productive projects that make the local economy dynamic and contribute to the improvement of FNS in the territory as a consequence of technical assistance, input delivery and constant support from the Universidad Nacional de Colombia and the Nazareth Hospital. In addition, the institutional support has been crucial in defining the structure and the formal and informal rules that govern the organization's behavior and consolidation.

Unlike the cases of Sibate and Sopo, this association is informal, which means that it does not adhere to government regulations. Beyond attending workshops, meetings and farmer's markets, the nine surveyed women said that they actively participate by giving their ideas and opinions, listening to others, making decisions and fulfilling assigned tasks. In addition, they stated that they have applied the acquired knowledge by making food trade and designing and implementing productive projects mainly related to boilers, swine production, and family gardens.

Socioeconomic characteristics of rural women surveyed in the municipalities of Sibate, Sopo and Sumapaz

In the three case studies, the ages of the interviewed women ranged from 23 to 75. Their educational level was low since more than half of them did not manage to finish high school. Their household composition, on average, included four people, and the great majority of the women were married or living in a common law union. The women were mainly engaged in housework tasks, caring for children and grandchildren, and, in some cases, field work, taking care of and breeding farm animals such as chickens, hens, pigs, and rabbits. They also took care of crops and home gardens and produced and sold cheese, curds, arepas, envueltos and desserts, among other products. In fact, these women spent more than 18 h a day on average on these kinds of activities, while their husbands or domestic partners devoted themselves mainly to farm work, jobs and livestock.

For the commercialization of their products, the women must leave their farms and villages and transport their products to the main plaza on the days that the farmer's markets are held. In that space, they sell their food directly to the final consumer in small units of measurement such as pounds, liters and pieces since the quantities of food they can transport themselves is limited. Besides, they often do not have fresh and ready to sell products.

When inquiring about the prices of the products, the women surveyed stated that they are set by the women themselves, the men of the association and, in some cases, by their husbands. However, when the women were asked if they knew the total cost of food production, either fresh or processed, 100% of the women of the three study cases declared that they did not know. Additionally, when asked what elements they would consider when establishing the total cost of production, the women did not consider important expenses such as their time, work, land leasing, transportation and public services. They only mentioned the seeds and inputs they acquired outside the household, a factor that harms the economy of their households.

Empowerment of rural women from the associative process

The participation of women in these three associations is incipient since only seven out of the 26 interviewed women stated that they hold positions within the board of directors of these associations. However, the vast majority of the women from the three studied cases declared that the associations presented an opportunity for them to outsource their products, expand their market, make food trades, and allocate a significant percentage of food for household consumption. They also stated that the associative process has allowed them to participate in areas where traditionally only men had access, such as technical assistance, agricultural inputs, financing of productive projects and access to training. This participation has strengthened food production, enabled them to receive their own income and given them the autonomy to freely decide how to spend it.

This is a situation that favors the FNS, as Quisumbing et al. (1995) indicate.

The results of this research also indicate that the associative process has also allowed rural women to strengthen abilities they had failed to develop at an individual level, such as cooperation, solidarity, teamwork, leadership, decision making, and economic autonomy, and provided opportunities to be outside their household, free time, chances to meet women in similar situations and the ability to be independent, among other benefits. In this way, the associative process has become a possible protective factor of the FNS of families and their community.

This is reflected in the following testimony of one of the female members of the Rural Network of Sumapaz:

"Belonging to the Nefwork...has allowed us not only to strengthen personal skills such as public speaking and expressing ideas, but has enabled us to acquire knowledge on food and nutrition. We have learned how to identify territorial problems and how we can create solutions to our problems by working as a team and knowing our skills, rights and duties. Participating in the Network has also allowed us to meet neighbors and friends, and, thanks to farmer's markets, we have gotten the opportunity to visit important places such as the Universidad Nacional".

These results agree with authors such as Zimmerman (1999), who states that empowerment is a construct in which strengths and individual competences and collective action are combined to improve the quality of life in a community. Authors such as Vázquez et al. (2002) have stated that "empowerment can contribute to improving the lives of women, especially rural women, since not only their personal development is emphasized, but also the structures and forces that marginalize, oppress women and put them at a disadvantage compared to men are transformed" (Vázquez et al., 2002).

However, it should be noted that, although the majority of women in all three cases acknowledged the fact that the associative process has promoted individual, economic and organizational empowerment, it is currently still very uncommon for them to make major decisions within these three associations since men continue to occupy the highest positions on the boards of directors of each association.

Additionally, for the FSN, this study revealed that the women in these three cases continue to experience conditions of disadvantage and inequality since, in a typical day, they are the ones who participate in the whole agri-food chain, guarding seeds, sowing, harvesting, raising animals, milking animals, and processing and/or transforming food; at home, they are responsible for cleaning and keeping things in order; at the food level, they are responsible for selecting, storing, conserving, preparing, distributing, and serving food, making sure all family members have eaten. Also, they are always monitoring food quality and safety.

On a typical day, they are also in charge of the medical care for the whole family; they supervise school activities and homework for their children and grandchildren and take care of the elderly and sick in their household. The rural female members of AMUC Sibate, AMUC Sopo and the rural network producer of life and peace of Sumapaz carry out these tasks daily without the help of their domestic partners or the other members of the household, except in some case when their daughters provide support.

Hence, this research revealed that the participation of women in these rural associations has encouraged empowerment processes, but, at the same time, has generated an additional workload for them. These women spend more than 18 h per day dedicated to their homes and families, producing and processing food, as well as participating in meetings, training, farmer's markets and other activities programmed by their association.

This situation can be compared with the results of the last National Survey on Time Use (DANE, 2017), which showed that Colombian rural women over ten years old devote on average 7 h and 52 min a day to unpaid tasks in their home and other households, whereas men spend 4 h and 50 min on the same type of activities. In addition, this research led to the conclusion that the increase in the workload of rural women was the result of women not being able to acknowledge, visualize and identify their work. They have not been able to distribute workloads within the household since the vast majority of these women affirmed in the survey that "It is worse for a woman to leave her children than for a man", that "the most important role of women is to take care of their home and cook for their families", and that "tasks such as changing diapers, and bathing and feeding children are the sole responsibility of women".

Although these associations promote individual and collective empowerment, in terms of decision-making, leadership, learning, and mainly economic autonomy, there is still a need to strengthen the associative processes through a cross-cutting gender approach that goes beyond using women as a tool. It is necessary to create spaces where men, women, young people, boys and girls question the traditional roles within the household, to create a shared vision of these roles, and to generate spaces where thoughts on the inequality and inequity between men and women can be transformed. As indicated by organizations such as the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) and the WFP (PMA, 2015), empowering women is not only a process by which women acquire the ability to choose, access to power, possibilities, control and autonomy in their own lives, but actually achieve it. Women must not only have the same skills, access to resources and opportunities as men, but also the necessary autonomy to experience those rights and opportunities in order to choose and make decisions about their own rights as members of society (PMA, 2015). Empowerment depends not only on women, but also on their environment and the possibilities for transformation in the personal, social, legal, cultural and economic spheres (PADEM, 2014).

Conclusions

The female members of AMUC Sibate, AMUC Sopo and the Rural Network Producer of Life and Peace of Sumapaz recognize that, little by little, their participation in these associations has promoted economic autonomy and the strengthening of their abilities and decision-making skills. These achievements are the result of technical assistance, agricultural inputs, training and productive projects that have been provided to them.

The results indicate that empowerment and the associative process of rural women can contribute to improving the FNS of their families and their communities. Indeed, when household income, technical assistance and food production for household-consumption increase, women are encouraged to make the right decisions regarding food, health and nutrition for all household members.

Nevertheless, these associative processes could also increase the workload of women. In the studied cases, the women not only dedicated several hours of the day to reproductive and domestic work that has historically and culturally been assigned to them, but they also devoted many hours of the day to fulfilling their commitments to the associations, for instance participation in meetings, workshops, and food production, processing and commercialization. Despite the fact that the associative processes in the three organizations have promoted individual and collective empowerment, government entities must take action to strengthen the cross-cutting gender approach. These actions should not only provide rural women with physical and economic resources to work in food production and processing, but they should also offer spaces for men, women, young people and children to question the roles within the household, to recognize the important role of women, to learn to distribute burdens within the household and to transform inequity and inequality.