Introduction

Succession is essential for the development of farms since it is related to sociocultural aspects, and it is fundamental to the sustainability and productivity of global agriculture. Given the advanced age of some farmers, promoting succession is key for avoiding the rural-urban migration of younger generations and preventing losses of farms that may lead to a reduction in agricultural production, affecting food security. This is an increasingly important issue since agriculture evolves and changes, making it more difficult for farmers to maintain endogenous cycles of succession and pursue innovative activities (Fischer & Burton, 2014; Hauck & Prügl, 2015).

Although succession was not originally a big problem because farms were large enough to divide them among all descendants (Stephens, 2011), inheritance has become more important since farms are smaller, and the number of famers has increased. However, this division has led to lower individual profitability in agriculture that, combined with lower availability of services in rural areas and climatic and biological risks of farming, usually makes it an unattractive activity for successors (Barnes, 2009). Another problem that farm succession faces is that urbanization and non-agricultural land uses (residential and commercial) have grown considerably, increasing land prices (Schumacher et al., 2019).

Succession planning is essential for the success of family businesses (Barclays Wealth, 2009), as it refers to the orderly transfer of management, responsibility, ownership, and control (Stephens, 2011). It can also include the transfer of the assets and can begin when the holder is alive. Thus, succession specifies when, how, and under what circumstances the management of farms will pass from the current operator to another person (Mishra & El-Osta, 2007).

The process of succession is affected by agricultural policy regimes, opportunities for diversification on and off the farm, gender, expectations of farmers, increases in land prices, and a sense of marginalization of farmers from society (Fischer & Burton, 2014). Additionally, succession is specific to the properties and depends on their structure and composition (Leonard et al., 2017). Farms possess socio-emotional wealth that is relevant and must be considered, due to their nature, as family businesses. Literature about family businesses considers non-financial aspects as drivers of family business behavior and contemplates their positive and negative consequences (Berrone et al., 2012; Hauck & Prügl, 2015). Families should examine their environment and family relationships since agricultural succession implies walking on a tightrope requiring understanding and empathy between generations (Mann, 2007; Hauck & Prügl, 2015). Family relationships are among the fundamental factors relating to succession suggested by Camfield and Franco (2019). These authors highlight family tradition, blood relationships, family participation, conflict management, trust, and communication between siblings as relationship issues that can influence succession. Also, the intention of the successors to take over the farm is determined by their attitude, behavioral control, and perceived norms within the farm (Morais et al., 2018).

Thus, the processes of succession are complicated and involve the interaction of sociocultural and emotional factors of the producers and their families. For this reason, these processes often represent a conflict for families. Additionally, the discussion of succession is a topic avoided in family circles (Romero-Padilla et al., 2020) due to the anxiety caused by the loss of reputation when problems relating to succession and innovation are shared openly (Hauck & Prügl, 2015). There are conflicting and contradictory wishes in the older generation regarding the final transfer of a farm (Conway et al., 2017). These wishes can generate "symbolic violence" from the owner towards the successors when the proprietor avoids delegating responsibilities and reiterates their indispensability in the operation of the farm. Despite these problems in succession, successor effects or the "new blood effect", referring to a successful succession process when appointed successors introduce innovations on the farm, imply many rewards like farm expansion and productivity (Kerbler, 2010). However, failure in these processes can turn into significant losses, financial insecurity, and family dissatisfaction (Ahmad & Yaseen, 2018).

The interest of the heirs in heritage depends on generational involvement and the type of family in which succession takes place (Soto Maciel et al., 2015; Camfield & Franco, 2019). Also, interest is related to the culture and traditions of rural households and territories (Pachón-Ariza et al., 2019). Since the process of succession is closely related to socio-emotional factors (Arreola Bravo et al., 2015), family history can influence its organizational and strategic performance, as family members can impose their values, objectives, and logic (Soto Maciel et al., 2015).

Regarding the rural and fishing sector of Mexico, 39% of farmers are over 60 years of age (INEGI, 2018). This fact is closely linked to the migration of young people to urban areas and increased marginalization, mainly in the central and southern regions of the country (SAGARPA-FAO, 2014). Although there are several studies on agricultural succession, this issue has not been widely studied in Mexico. Thus, information on this topic is important, given the growing urbanization of central Mexico, where people easily migrate from the countryside to the city searching for better opportunities, resulting in the abandonment of agriculture because it is not attractive to new generations.

The objective of this research was to analyze land transfer on family farms, after the passing of an incumbent. The study took place within the agricultural farms located in central Mexico and includes the phases that this process encompasses. The research was carried out with the assumption that succession is a long and complex process involving the interaction of a high number of sociocultural and emotional aspects. To achieve this goal, the multiple case study method was used with producers who went through a recent succession process.

Materials and methods

The study adopted a qualitative approach using the multiple case study method. This method was chosen as a convenient tool for studying complex phenomena from unique stories (Tasci et al., 2020); it also enables an in-depth exploration within specific contexts (Rashid et al., 2019). In addition, case studies are usually useful to understand how succession is implemented in family businesses, and their wealth, depth, and closeness allow the understanding of the characteristics of each family business (De Massis & Kotlar, 2014). The qualitative approach in the study of succession processes provides a deeper understanding, and addresses beliefs, motivations, and attitudes of family members (Bertoni & Cavicchioli, 2016).

In the multiple case study methodology, the selection of cases is important. De Massis and Kotlar (2014) argue that the sample cases should be selected for theoretical reasons. In this research, the cases were selected because the participants went through a similar situation within a succession process. In this way, the producers were selected under the criterion of having gone through a family farm transfer after the incumbent's death. In all cases, the land had been transferred in the last 5 years or the process was still in progress. Additionally, the participants must have been willing to share their experiences given the sensitivity of the topic.

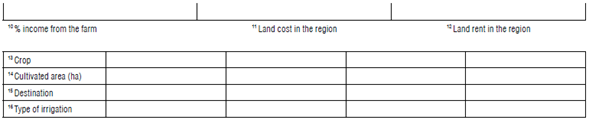

The producers interviewed were contacted through a "local key informant" who knew the producers in the area and understood their willingness to speak openly and honestly about their succession process. The interviews were conducted with 12 farmers in central Mexico between July and September 2019. The area of the average farm was 5 ha and the main crops cultivated were maize, bean, alfalfa, broccoli, green oats, and avocado.

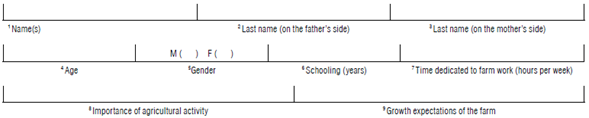

Data collection was carried out through semi-structured interviews that included two main sections. The first section consisted of basic questions about the producer and the farm, while the second section included questions relating to the succession process they had gone through (Supplementary material 1). The interviews were recorded and transcribed. A content analysis was performed to find similarities and differences between the interviewed producers and to establish the categories and groups. The materials were imported to Atlas.ti and codes were established. This way, it was possible to differentiate succession pathways through the following variables: situation of the holder's spouse, number of descendants, distribution of the patrimony when the holder was alive, existence of talks about succession between the holder and their descendants, affective relationships between the producer and his spouse, involvement of descendants in agricultural work with their father, and affective relationships between the producer and his descendants.

The information on succession was then systematized and analyzed, and the factors associated with them were discussed. The sequence of events and the relatives involved in the process of succession were presented in five succession stages, adapted from the succession phases established by Belausteguigoitia Rius (2012): diagnostics, planning, training, transfer, and culmination. Finally, the importance of socioeconomic, emotional, and cultural issues in the decisions that producers make in their processes of succession was discussed.

Results and discussion

Of the twelve producers interviewed, ten were men and two women. The average age was 58 years, and only one woman had no experience in agricultural activities. Regarding the level of education, two producers completed primary school, two producers finished secondary school, five producers graduated from high school, and three had a bachelor's degree.

For the producers interviewed, the main asset of their farm was the land. Therefore, when we refer to succession and inheritance of the patrimony, we refer only to the land.

Succession pathways

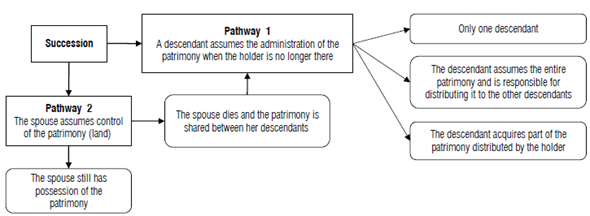

Each farm underwent a specific process of succession due to the diversity of income levels, land value, family structure, agricultural systems, the emotional nexus and socioemotional characteristics in the family. Our findings agree with those of Leonard et al. (2017) who state that there is no specific path to succession. Nevertheless, two basic succession pathways were identified, one of them is generally a transition to the other. Thus, the final scenario leads the descendants to assume the administration of the farm (Fig. 1).

The description of these pathways and their multiple aspects are presented below.

Pathway 1: a descendant assumes the administration of the patrimony when the holder is no longer there

In this scenario, three possible situations were found. In the first one, there was a single descendant since the successor had no siblings. His mother died years before his father, so when his father died, the farm was left under his management. Although the successor had a profession and exercised it, the agricultural activity was profitable, motivating him to continue with his father's work. So, factors such as competitiveness and profitability of the farm indirectly promoted intra-family succession (Cavicchioli etal., 2015). An important aspect that the successor commented was that, since he was not involved in agricultural activities, after inheriting the farm many people approached him asking to buy the land. In this situation, if the heir had had a higher opportunity cost outside of agricultural activity, it is most likely that he would have sold the land, and it would have remained in agriculture, but with other owners.

The second situation occurred when one descendant received the entire property and was responsible for distributing it among the other descendants. In this situation, we found four farmers with a descendant in charge of distributing the land among his siblings according to the provisions of the holder. In these cases, the holder shared with the family the percentage of the patrimony that corresponded to each descendant. Despite this, the holder did not designate in all cases the location of the properties to be distributed; so, when there was no established location, the descendants raffled or agreed on the sites. This fomented displeasure among some heirs who did not agree with the results. In this scenario, the incumbent probably preferred to avoid problems with his descendants about the designated location of the patrimony. This constituted weak planning for the farm that brought problems between the descendants.

Finally, in the third situation, the successor acquired part of the patrimony distributed by the holder before his death. That does not mean that the inheritance was carried out in a formal way, with the existence of a testament or succession list; however, all the descendants were aware of their father's decision. The two producers in this situation received a higher percentage of the patrimony than the other heirs. Also, the holder designated a small area of land to some descendants for building their houses or to begin establishing their own farm. In the analyzed cases, the holder assigned a different proportion of land to their descendants, causing disagreements between them.

Pathway 2: the spouse assumes control of the patrimony (land)

It is common that the holder does not formally define a descendant as successor. This situation can take place due to the holder's fear of creating uncomfortable situations or losing authority, or simply due to an unforeseen death. In these cases, the administration of the patrimony invariably falls on the spouse. In this pathway, the successor, widow, and mother of the family seeks to give continuity to the prevailing situation before the death of the head of the family. Even where there are dynamic land markets, renting or selling the land are options to obtain income without engaging in agriculture. Subsequently, a new process for the designation of the land begins that is carried out by the mother towards her descendants. Although it is possible that the heirs continue working on the farm, if the land belongs to the holder's spouse, they generally do not invest, innovate, or improve the farm since it is not clear who the final successor will be.

Thus, the "symbolic violence" mentioned by Conway et al. (2017) is seen in this scenario when the mother refuses to transfer the land to her son, arguing for his lack of capital. Also, the barrier of the "successor effect" is seen since the son wants to take over the farm, but his mother does not allow it.

For three of the producers interviewed, their mother oversaw the designation of the available land. In these cases, when the mother died, legal procedures began for the assignment of the property to each descendant. In this scenario, disagreements were related to the final percentage that each descendant received. In the end, the descendant who cared for his mother was the one who obtained the highest percentage, causing discontent among the others.

This group included a scenario with two widowed women. One of them has already made the patrimony designation and worked together with one son, while the other has not yet appointed her successors and rents the land to other producers. Regional conditions differed between these two participants; the first person was in a large agricultural area. Additionally, she has been involved in agricultural management for years and considers this activity to be profitable. The other woman rented her land because, according to her statement, she would not know how to handle it.

In this case, the land was in a peri-urban area, where the price of land is high and agriculture becomes less important in the face of urban growth (Romero-Padilla et al., 2020). The two women also acquired the responsibility of deciding whether to continue with the agricultural activity or to sell or rent the land.

Stages of the transference process

To understand the result of a succession, it is necessary to study what happens before and after the transfer of assets (Stephens, 2011). For this reason, to specify the planification of succession among the studied farmers, we analyzed the five phases of the succession process in the family businesses proposed by Belausteguigoitia Rius (2012): diagnostics, planning, training, transfer, and culmination.

Phase 1. Diagnostics

According to the producers, this phase is complicated since if they are "ejidatarios", they must choose a single successor among their family members. In México with agrarian reform, the land and water were granted by the president to a group of people named "ejido". Each person of this group is called an "ejidatario" and has the rights over a piece of land and the right to vote in the assemblies of the "ejido". New members of the "ejidos" obtain land rights, in order of importance, through a) inheritance, b) cession or direct transfer, c) purchase from another member, and d) leasing agreements (Barnes, 2009).

This implies that they would fear the disagreement among the non-chosen. In most cases, the holders did not talk to the family about their decision, and, therefore, no preparation for the successor was made. In some cases, the designation of the new successor was known only after the holder died.

For the interviewed producers, this phase involves the affective, economic, and emotional relationship that they have with their family, and it implies the condition of support that the holder expects to receive from the people identified as heirs once the transfer has been made. In turn, according to the interviewees, not only the direct successor should be considered but also his family. In this way, holders look for ways that their descendants can develop their personal work and emotional projects (López Castro, 2009).

In general, for the cases analyzed, the holders provide the diagnostics of their succession based on the economic and affective security that they would have in the future. Thus, the current economic position of the holder and his descendants affects the succession. For example, alternative sources of income, such as a retirement income, provide economic security to the holder for future years. However, this pension could motivate the transfer because the farm is not the only source of income for the farmer (Mishra & El-Osta, 2008; Grubbström & Sooväli-Sepping, 2012).

Phase 2. Planning

A formal planning phase was not found in the processes of succession studied. However, the holders talked to their family about how the transfer of the heritage would take place. In the analyzed cases, the holder sometimes started the distribution of the land so their descendants could establish their homes. In other cases, the holder designated a land area for the descendants to work but without a testament. Therefore, there was no document guaranteeing succession of the property. This at times caused frustration and disharmony among family members.

Sometimes the holder set a fraction of land apart, as an economic asset to sell in an emergency, or to cede it, at a specific time, to the descendants who would support the holder economically and emotionally in their old age. According to the anecdotes of the interviewees, the holder made changes based on the expectations and support they had from the descendants. Thus, as mentioned before, descendants did not invest in the farm because they did not know who the final heir would be.

Phase 3. Training

In the cases analyzed, no training phase was found because the successor frequently did not know whether they were the only successor. In the studied cases, sometimes it was possible to see the rungs in the succession ladder described by Errington (1998), because it was not clear who the final heir would be. This is a common problem for the farmer's boy since the holder delays his decision to leave the farm as much as possible and does not delegate sufficient management responsibility to a successor (Uchiyama et al., 2008).

In some narrations, the successors stated that they had worked on the farm with the holder and had been involved in production and had also indirectly received training. In some cases, the holder commented to the successor that they would oversee the farm. Despite the above, not having an official designation kept the successor uncertain and prevented them from becoming fully involved in the production processes.

Therefore, it is important to consider that an intervention of parents in the motivation and involvement of agricultural labor could increase the intention of the successors to take over the farm, and the necessary factors could be developed to motivate interest in managing the agricultural business.

Phase 4. Transfer

This phase is inevitable, and according to the producers interviewed, it is the most complicated and the longest (Belausteguigoitia Rius, 2012). In the farms analyzed, this phase began after the holder died.

As stated before, the transfer of the farm occurs through two basic scenarios, the spouse of the holder assumes control of the patrimony, or a descendant assumes it (Fig. 1). In both cases, the holder could previously assign part of his land to his other descendants.

Phase 5. Culmination

A multiple succession was noted in the studied cases that could be caused by stress within the farm family, resulting in friction between the family members. There are a few cases where some descendants continued to work the lands inherited from the holder and buy out those who did not intend to continue in agriculture. However, this process could have some complications generated by the need to buy by other siblings and social aspects of the family unit such as the extent to which family members can work together (Burton & Walford, 2005). This intention to continue in the activity is closely related to the profitability of the farm. Thus, a successful farm links the successor to the land (Fischer & Burton, 2014).

Socio-emotional aspects and personal relationships influence the duration and complexity of the succession processes. However, the continuity of agricultural activity is largely determined by the opportunity costs of alternative uses of the land and of family work.

The culmination implies the consent of the holder's descendants after the long transfer process. Thus, in the end, those involved are satisfied or resigned to the results of the succession, and some of them continue working the farm. In this research, there are succession processes that have not reached their culmination because the transfer phase has been very long.

In some processes, the land was finally sold by the successors because the farm was not considered profitable, or the successors had higher expectations about other sources of income. Also, there were some cases where the land was rented, mainly when the farm was inherited by the spouse, and she did not know how to manage it. Another scenario was the personal use of the patrimony for non-agricultural purposes, mainly housing construction.

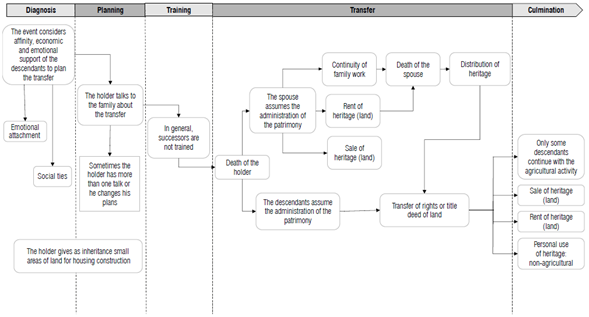

The typical succession process

With the comprehensive analysis of the five stages of the succession process, the typical process was designed for the cases studied (Fig. 2).

The common element in the successions that we studied is that they practically lacked the formal planning and training phases. Indeed, the first three stages were carried out unconsciously without explicit analysis or reflections. The holder avoided committing to the successors to prevent conflicts or disappointments from happening and was able to make adjustments at any time. In the end, this approach makes the next two stages, training and transfer, less effective. The emphasis was on the transfer that, according to the interviewed producers, is the most complicated and longest phase. The culmination phase usually resulted in the fragmentation of the farm and the abandonment of agriculture by most of the descendants.

Succession and continuity of agricultural activity

Succession can take place when the incumbent is still alive, and he participates in the management of the farm along with the successor, so the successor gets training. However, succession in the case studies was not planned; it rather happened because of the death of the farm holder or their inability to continue in agricultural production. At the time of the transfer of patrimony, the individual interests of the possible heirs prevailed, frequently in a framework of distrust. This results in fragmentation of the patrimony making the continuity in the agricultural activity less viable, without a route to farming that would provide an appropriate succession and efficient agriculture (Chiswell, 2016).

Even when the decisions about management of the farm and inheritance follow an economic focus, and profitability is the main motivating factor for continuing in agricultural activities, the interviews revealed that holders and successors also have a need to satisfy personal goals. According to Gómez-Mejía et al. (2007), some farms continue through generations not only because they are efficient or profitable but also because they satisfy the owners and successors as family businesses, providing successful aging and social and personal identity to the older farmers (O'Callaghan & Warburton, 2017). However, in these cases studied, the greatest motivation to continue in agricultural activity was profitability that is related to the type of production system and the destination of production (Romero-Padilla et al., 2020).

In the processes of successions analyzed, several factors interacted and affected the decisions made by holders and successors. For example, they were influenced by the environment in which the farm was located and the circumstances in which the producer worked. The value of the land was another important variable since proximity to cities increased the value of the land for non-agricultural uses.

Cultural and traditional aspects were also relevant in succession and have an influence on the continuity of the agricultural activities in the cases analyzed. Aspects such as gender, birth order, and age play a role in whether the successor will continue in agriculture or not. Thus, male and first-born successors are more likely to take over the farm, acquire a greater proportion of the assets, or oversee the assignment (Cavicchioli et al., 2018). Although sometimes it is the wife who assumes administration of the land, the final transfer follows the same details for her descendants.

The narratives of the interviewed producers showed that the processes of succession are affected considerably by affective and emotional issues. The emotional attachment is related to the financial support the holder receives from his descendants and the economic security they will provide when the holder cannot continue the agricultural activity, and his sources of income are null or scarce. Thus, the holders maintain their authority over their descendants in an unrecognizable and silent way, exercising symbolic violence (Conway et al., 2017).

Many holders preferred to assign the land to their spouse to provide security for her or simply to leave her the uncomfortable decision of choosing a successor. Finally, the main problems in the processes of succession are related to personal feelings and disagreements of the people involved.

These are generated by the dissatisfaction with the area or location of the assigned patrimony.

Conclusions

The processes of transfer of farms are not planned, and decisions or actions are rarely taken to prevent future problems and difficulties. Thus, succession is long and complex and frequently has permanent consequences for family harmony and the patrimony. There are multiple aspects that depend on family relationships and the economic, social, and cultural conditions in which the farm operates.

In the most common scenarios, the continuity of the farm is unlikely due to the tendency to fragment the land and the lack of interest from family members to maintain agriculture as a source of income. Thus, at the time of transferring the land, individual interests prevail over collective ones that frequently reduce the economic viability of the farm.

In this research, the spouse has an important role in the transfer process, as she is often an executor of the main asset that is the land when the holder dies and, subsequently, the land is distributed to the descendants. This situation is important since it delays the final transfer process and the total involvement of the successors in the agricultural activities.

This vulnerability of family farming to the processes of succession represents a challenge since they alter the management of the farm and sometimes compromise continuity.

Faced with this possibility, strengthening the stages before the transfer (diagnostics, planning, and training) would help to achieve more effective and less risky succession that might prevent losses of Mexican farms. This requires those involved in the succession to be willing to seek support or advice.

In Mexico, there is no culture of succession and generally the succession process starts with the incumbent's passing. In this sense, public policies that support agrarian transference through training and advisory programs are relevant, especially for profitable farms where continuity of agricultural activity is intended and where development is limited by problems of inheritance.