Introduction

The Andean blackberry (Rubus glaucus Benth), also known as Castilla blackberry, is a fruit belonging to the group of berries, many of which have been found to offer multiple benefits such as high fiber (Howarth et al., 2001; Chutkan et al., 2012) and antioxidant contents (Mazza et al., 2002; Burton-Freeman et al., 2016) and cholesterol (Jenkins et al., 2008; Jeong et al., 2014), sugar (Martineau et al., 2006; Törrönen et al., 2012) and insulin (Törrönen et al., 2013) regulation properties. Additionally, this fruit represents an important source of polyphenols, carotenes, and vitamin C (Alarcón-Barrera et al., 2018).

Marketed in Colombia through both agroindustry and fresh market channels, the Andean blackberry is consumed mainly in the form of juice, pulp, jam, preserves, sweets, and colorants (Cámara de Comercio de Bogotá, 2015). Despite its acceptance in the market, fruit safety problems related to the excessive use of agrochemicals for the crop production have become notorious in recent years, potentially putting farmer and consumer health at risk. Naranjo Marin (2011) has observed the Andean blackberry production in Colombia to be highly dependent on organophos-phate insecticides for pest control. This author found these products to be applied outside the technical parameters recommended for their use and management, increasing the presence and concentration of their active ingredients in the fruit and, therefore, exceeding the corresponding maximum residual limits (MRLs). Furthermore, the FAO/ WHO alliance on pesticide residues (JMPR) determined that some of the pesticides commonly applied to the Andean blackberry should not be permitted and their use represented a risk for human health (Naranjo Marin, 2011).

Farmer's actions to migrate towards a cleaner and organic production of the Andean blackberry have been gradually taking place in the departments of Cundinamarca, Antioquia, and Santander. Although not significant, this cleaner production is being marketed through specialized stores and agroecological markets but has not yet reached supermarkets, which are the main trading channel for organic foods in Colombia. By 2013, agroindustry, fresh market, and exportation channels respectively accounted for 60%, 38% and 2% of the total production of the nonorganic Andean blackberry in the country (MADR, 2013). This setting offers an opportunity to develop an internal market for a cleaner and organic Andean blackberry.

Little is known about the size of the Colombian organic market and the actual areas destined for this mode of production. In addition to not being regularly updated, the figures about these areas are substantially different from the corresponding international data (Martínez Bernal et al., 2012). Furthermore, neither the Ministry ofAgriculture nor the certification companies, the organisms in charge of creating the normative framework and issuing the certifications, have made the figures on certified organic areas publicly available. Of the total area of 31,621 ha cultivated organically by 2017 (Willer & Lernoud, 2019), 5.52% was represented by tropical and subtropical fruits such as banana, mango, strawberry, guava, pineapple, and plantain (Sánchez Castañeda, 2017; Willer & Lernoud, 2019). According to Willer and Lernoud (2019), the area destined to organic agriculture in Colombia has had an unsteady dynamic, with ups and downs throughout the 2010-2018 period. Additionally, the Colombian organic market is still in its infancy. Despite the sales growth during the last years, more than 90% of the national organic production is exported (Becerra Elejalde, 2018). Domestic consumption is limited by factors such as high prices associated with organic fruits and vegetables, little available information on their production and benefits, and low added value (Martínez Bernal et al., 2012).

Some of the existing literature on organic consumer segmentation has drawn attention to the importance of designing sound marketing strategies and public policies that consider the specific needs and profiles of consumers (Gil et al., 2000; Chinnici et al., 2002; Nie & Zepeda, 2011; Maciel et al., 2015). Studies on organic consumer segmentation have provided valuable information on the differences among groups within this market niche, which are mainly related to product availability and information and pricing strategies (Nie & Zepeda, 2011). However, these results should be considered in light of some of the points made by Claycamp and Massy (1968), such as the difficulty in finding mutually exclusive segments and the existence of logistic constraints to target specific groups. When reviewing the literature, two segmentation types for consumer can be found, namely those within the organic niche and those resulting from mass market assessments.

Reviews on this topic by Hughner et al. (2007) and Pearson et al. (2011) have pointed out that, despite the many studies to determine standard segmentation criteria for organic consumers, a clear profile remains elusive due to the multiple factors and complex decisions involved in organic food purchasing (Zepeda et al., 2006). Segmentation has resorted to multiple consumer classification criteria such as by socioeconomics and demographics (Chinnici et al., 2002; Maciel et al., 2015), food and non-food related lifestyles (Gil et al., 2000; Mora González et al., 2010; Nie & Zepeda, 2011), values (Chryssohoidis & Krystallis, 2005; Salgado Beltrán, 2019), behaviors (Chinnici et al., 2002; Nie & Zepeda, 2011), attitudes and perceptions (Chinnici et al., 2002; Mora González et al., 2010; Higuchi & Avadi, 2015; Maciel et al., 2015; Salgado Beltrán, 2019), purchase frequency (Chinnici et al., 2002; Krystallis et al., 2006), and level of awareness (Krystallis et al., 2006).

Explaining that individual lifestyles are more likely to influence the willingness to pay (WTP) for organic products, Gil et al. (2000) proposed a market segmentation for Spanish food shoppers based on consumer lifestyle rather than socioeconomic variables. By clustering individuals according to diet, exercise, and private and personal life habits, they identified three groups: actual organic food consumers, likely and unlikely organic food consumers. Mora González et al. (2010) also found that lifestyle and attitudes can provide a more accurate explanation on organic wine consumption in Chile. They found the consumer segments to be mainly marked by consumption habits, leisure activities and food-lifestyle, as well as perceptions on the contribution of organic production to the environment and the actual taste of organics. These criteria allowed identifying three groups, indifferent and positive consumers towards organic wine, plus actual organic wine consumers. These groups were differentiated mainly by organic wine frequency consumption and general food preferences (Mora González et al., 2010).

Higuchi and Avadi (2015) segmented organic consumers in the metropolitan area of Lima, Peru, by focusing on consumer's attitudes towards organics, their perceptions about their attributes, the resulting ecological welfare, health concerns and food safety and convenience. These authors used the segmentation framework of the Hartman Group (2020) that categorizes organic buyers into three groups, core, mid-level, and periphery. The core consumer buys organics for self-interest and welfare reasons, the periphery consumer buys them for convenience (proximity and novelty), and the mid-level consumer has a more integral approach by also considering environmental issues. Similarly, by considering consumer's attitudes and perceptions about organics, Nie and Zepeda (2011) found three US food shopper segments, adventurous, careless, and conservative uninvolved consumers. They further stated that the factors they addressed probably reflect psychological profiles and, as such, may provide information about the motivations influencing the purchase of organics.

In a more value-centered segmentation, Chryssohoidis and Krystallis (2005) proposed a Greek organic-consumer profile based on personal values that might motivate or hinder the consumption of organic food products. Their list of values was grouped around three factors: "belong" (i.e., interpersonal relations), "self-respect" (personal values), and "fun" (non-personal values). The relative importance assigned by the consumers to these factors allowed differentiating four clusters: "explorers", featured by attributing high importance to all three factors; "loyal organic buyers", who gave average importance to self-respect and fun; "health-conscious organic buyers", who give least importance to fun and belonging, and "independent", who stood out for giving little importance to belonging values.

To provide valuable information for farmers and marketers willing to commercialize organic Andean blackberry, this study presents a market segmentation for organics consumers, with emphasis on blackberry consumers. This assessment is based on the Andean blackberry preferences of this particular target group, the price they currently pay for the non-organic Andean blackberry, their WTP for an organic version of the fruit, and their data on demographics, socioeconomics, lifestyle, environmental attitudes, and perceptions about organics. The results of this study will support not only the development of communication and marketing strategies by the Andean blackberry farmers and marketers, but also the design of public policies aimed at benefiting all the agents of this supply chain, including the consumers.

Materials and methods

Data and survey design

The study was conducted in the cities of Bogota and Medellin, the two largest cities and organic product markets of Colombia. As there was no pre-existing database or list of organic consumers, a sample size of 164 participants to be interviewed was defined through a tailored formula for unknown populations, at an 80% confidence level and a 5% margin error. Stratified random sampling was used, considering the marketing channels as strata and assuming differences between the organic consumers of each channel in terms of lifestyle, trust in organic foods, and attitudes towards environmental and social issues. The sales percentages of the different marketing channels, as estimated from the information provided by organic food marketers in both cities, were used to estimate the proportion of consumers to be interviewed in each channel. These marketing channels corresponded to retail stores, health-food stores, sale points of farmer organizations and agro-ecological markets.

A questionnaire was used for data collection consisting of eight sections which evaluated different consumer features: i) socio-demographic features, ii) lifestyle, iii) environmental attitude, iv) criteria when buying the Andean blackberry, v) attitude toward organic fruits and vegetables, vi) confidence in organic marketers and certifications, vii) organics consumption habits, and viii) perception of barriers to increasing organic food consumption (Supplementary material 1). Most of the responses were scored using a Likert scale and a few were defined as yes or no questions. Due to difficulties in obtaining income related information through the survey, socioeconomic strata were used as a proxy income level variable. This socioeconomic stratification of residential properties, which is the basis of the public utility billing strategy, determines that those who have higher economic capacity pay more for their public utilities, whereas the opposite occurs for the lower strata (Congreso de Colombia, 1994). To encourage participation in the survey, an incentive in the form of organic fruits or vegetables was given to the consumers.

Data collection took place from July to September 2019. To take advantage of high peak consumer shopping, specialized stores were visited on those days they received fresh product, while retail markets were mainly visited on weekends and fruit-and-vegetable discount days. Consumers were approached while in the vicinity of the organics section at the specific market channels. The criteria used to decide the consumers to be included in the sample were those who: i) actually consumed organic fruits and vegetables, as reflected in the purchase of these products; ii) were aware of the term "organic" as chemical-free, and (iii) consumed Andean blackberry.

Statistical analysis: market segmentation

To identify market segments within the target population (i.e., organics and the Andean blackberry consumers), a clustering was run on a multiple dimension database containing the consumer's information on socio-demographics, lifestyle, environmental attitudes, preferences related to the Andean blackberry attributes and consumption, and perceptions and knowledge about organic food (fruits and vegetables). No hypotheses were specified before the data were collected as the analysis was data-driven.

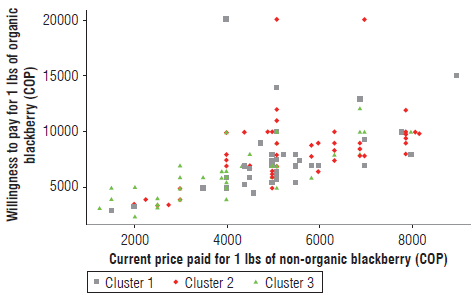

The cluster analysis was implemented in a Gower's dissimilarity matrix (Cower, 1971) used to compute the distance between the different individuals in the dataset. Information on the 164 consumers was contained in 86 variables of continuous and categorical nature. Gower's distance between consumers, resulting from integrally computing all the variables, yielded the dissimilarity matrix, which was subsequently used to run a cluster analysis. After trying different numbers of groups, a clear separation among three consumer segments was evident, mainly marked by the relation between WTP for the organic Andean blackberry and the current price paid for the non-organic version of the fruits (Fig. 1). Mathematically speaking, the three resulting segments exist in an 86-dimensional space, corresponding to the number of variables on which the clustering was based. Most of the statistically significant variables across the segments were identified using ANOVA and Fisher's tests.

Results and discussion

Although it was the cluster analysis (as obtained by computing the 86 variables under study) that allowed identifying the three segments of organics consumers, these actually derived their names from the plotting of the above-mentioned price-related variables ("WTP for the organic Andean blackberry" and "current price paid for the nonorganic version of the fruit"). This two-dimensional display resulted in three price bands in which the participants of the survey were paying (and willing to pay): relatively low, medium and high prices, respectively corresponding to the "Budget", "Medium", and "Premium" consumer segments. Thus, an intuitive and more natural understanding of the clustering results was provided, as shown in Figure 1. Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4 describe the groups through these and other significant variables.

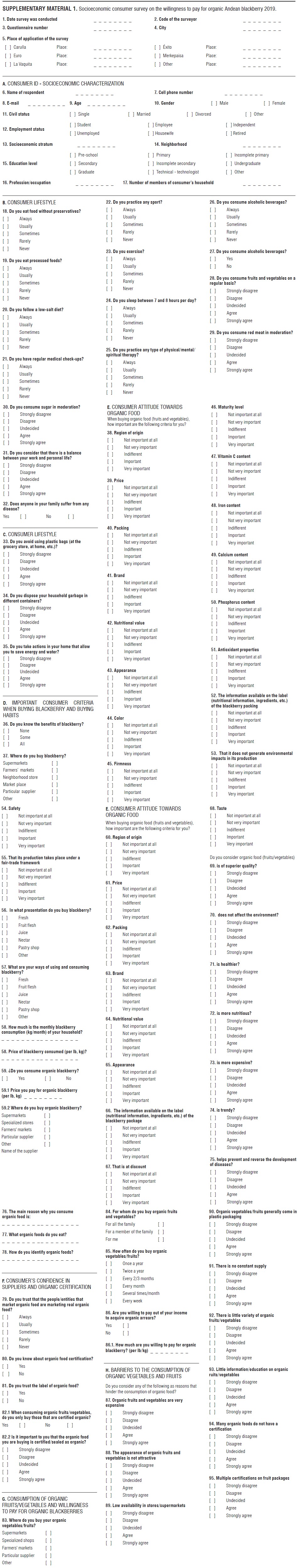

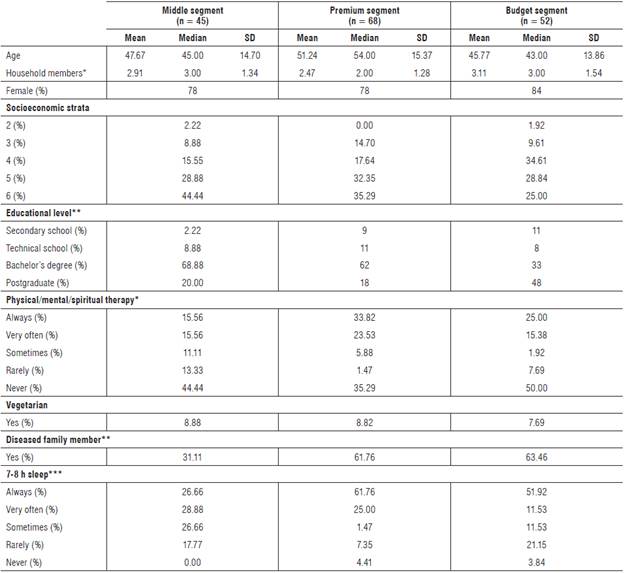

TABLE 1 Socioeconomic and lifestyle profiles of consumer segments.

SD - Standard deviation. Significance levels of 5%, 1%, and 0.1% are indicated by *, **, and respectively. The significance levels of continuous and categorical variables were estimated using ANOVA and Fisher's test, respectively.

The findings suggest that the three consumer segments in question were mainly shaped by their preferences on the Andean blackberry and perceptions about organics. As mentioned by Chryssohoidis and Krystallis (2005), organic consumer groups share many features, explained by the similar nature of the overall sample of respondents. Similarities were mainly found in perceptions and beliefs surrounding organic food, considerations about consumption increase barriers, and environmental and health awareness.

Middle-aged women were found to be the main purchasers of organics across the three identified segments (Tab. 1). However, this does not necessarily imply that they are more interested in organics than men, but simply that they usually do the food shopping for the household, which is consistent with multiple studies on organics (Davies et al., 1995; Roddy et al., 1996; Schifferstein & Ophuis, 1998; Cicia et al., 2002). As shown in Table 1, significant differences among educational levels showed that the budget segment had the most educated consumers, with almost half of them holding a postgraduate degree. Regardless of the statistically insignificant socioeconomic stratum differences across segments, half of the consumers of the Budget group did not live in the highest strata.

Across the three segments (Tab. 1), most consumers were active in healthy practices, confirming the association between healthy lifestyle and consumption of organic foods (Gil et al., 2000; Mora González et al., 2010; Nie & Zepeda, 2011). In this regard, premium consumers were the strictest, as shown by their permanent exercise routines, very frequent consumption of fruits and vegetables, low salt and sugar intake, and involvement in mental and spiritual therapies. This finding relates to that of "core consumers" in Higuchi and Avadi (2015).

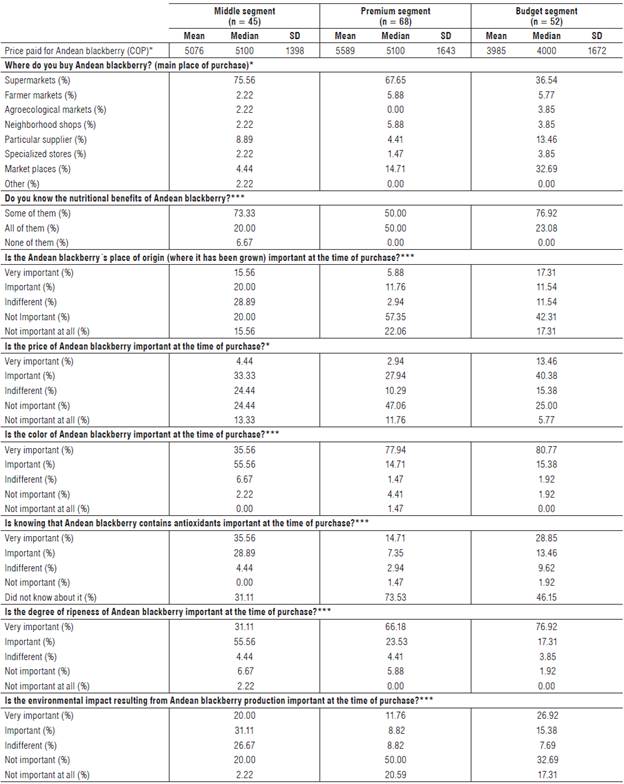

Regarding the Andean blackberry preferences and attributes (Tab. 2), the medium segment contained the highest proportion of consumers who considered both the multiple benefits of the fruit and the packaging label (e.g., vitamin C, calcium, phosphorus, and antioxidant contents) as very important or important. As can be seen, this is the segment most knowledgeable about the fruit. Given the willingness of middle consumers to be informed, they could rapidly develop an interest in the organic Andean blackberry if they were provided with information about the current use of agrochemicals on the non-organic Andean blackberry crops and the benefits of organic production. Additionally, most middle consumers also gave great importance to the origin of the fruit and the likely environmental impact of its production, which suggests that communication strategies emphasizing local consumption of the organic Andean blackberry could be effective with them.

TABLE 2 Andean blackberry preference profiles across consumer segments.

SD - Standard deviation. Significance levels of 5%, 1%, and 0.1% are indicated by *, **, and respectively. The significance levels of continuous and categorical variables were estimated using ANOVA and Fisher's test, respectively.

Most budget consumers considered price, color, appearance, ripeness stage and place of purchase as "very important" criteria when deciding to buy the Andean blackberry fruits. This indicates they gave the highest value to money and that a marketing strategy combining affordable prices, good quality and an ad hoc approach to different distribution channels (e.g., supermarkets, marketplaces, and particular suppliers) could awaken their interest in organic Andean blackberry. The foregoing is consistent with the current Andean blackberry price paid by budget consumers and their WTP for the organic version, which are the lowest within the three groups.

In terms of these prices, premium consumers were willing to pay 40% more than budget consumers and 10% more than medium consumers, despite the fact that this last group had a higher frequency of purchase. One likely reason explaining why premium and medium consumers were paying (and willing to pay) more for the fruit (and its organic version), could be their higher socioeconomic strata, used in this study as a proxy for income. This coincides with previous findings of several studies (Nandi et al., 2017; Vapa-Tankosi C et al., 2018; Bhattarai, 2019) associating higher income with higher willingness to pay for organics. Nonetheless, the assumption that consumer's public utility expenses can be extrapolated to estimate their food budget assignation is certainly an ambitious one and, as such, needs to be interpreted with caution. These findings suggest that there may be a potential market for organic Andean blackberry beyond the highest socioeconomic strata, which could positively respond to competitive price strategies and be the target of future consumer-support policies.

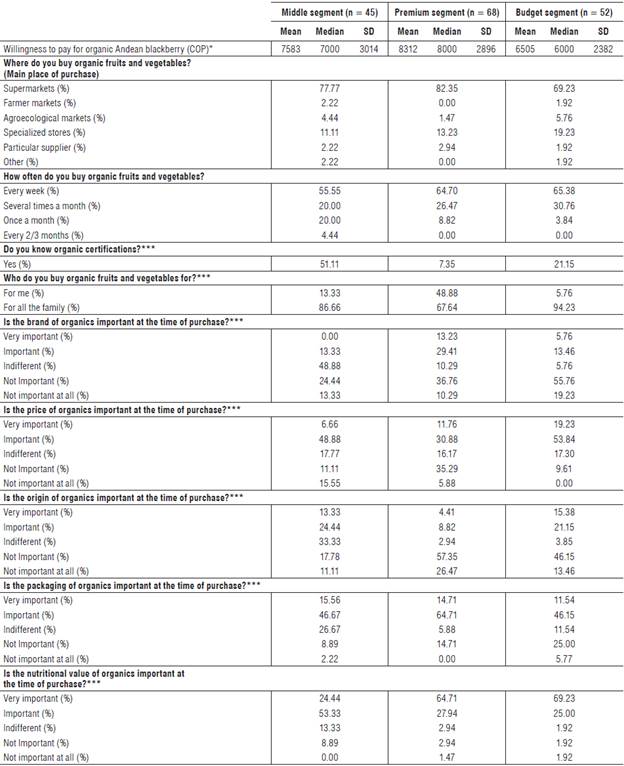

Results on consumption of organics are shown in Table 3. More than half of the participants interviewed in all segments were buying organics for all the members of the family on a weekly basis. A slightly higher proportion of these consumers belonged to the budget segment. Furthermore, 50% of the middle consumers recognized the Colombian ecological foods certification, while 7% and 20% of the premium and budget consumers, respectively, did so. This shows that, at least for the medium segment, even though the organic certification intends to guarantee that a food product is truly free of chemicals, consumers do not always consider this as a purchase-defining criterion. Despite this, more than half of the premium and budget consumers regarded certification of the organic product as important, whereas half of the medium consumers did not. This result can be interpreted considering what Hughner et al. (2007) have stated on consumer's likely distrust and skepticism with regards to certification authorities and agencies and organic food credentials. Interestingly, more than 60% of the consumers in the three groups expressed trust in the (non-certified) "organic" label as well as in the marketers of organic products. Thus, the distrust in certification can be overcome by the mentioned trust in organic producers and marketers (Veldstra et al., 2014).

Regarding important criteria at the time of buying organics (Tab. 3), most of the premium consumers gave more importance to the brand and packaging of these products than did the middle and budget consumers, while the latter considered label, origin, price and nutritional value to be more important. In terms of perceptions and beliefs surrounding organic food, the segments coincided on several criteria and barriers that may hinder the expansion of these products: participants from the three segments believed that the high price of organics is the main barrier to increasing their consumption, agreeing with Nandi et al. (2017) and differing with Chryssohoidis and Krystallis (2005), who found that price is not as important as the organic's limited availability. Other factors hindering organics consumption were lack of knowledge about organic certifications and the plastic packaging of these products, considered by some consumers as a contradiction of what these products environmentally represent. Such packaging has been a requirement of marketers such as supermarkets to differentiate organics from conventional products, and even if some organics marketers have started using materials other than plastic, there is still some non-acceptance from consumers.

TABLE 3 Attitudes towards organics across consumer segments.

SD - Standard deviation. Significance levels of 5%, 1%, and 0.1% are indicated by *, **, and respectively. The significance levels of continuous and categorical variables were estimated using ANOVA and Fisher's test, respectively.

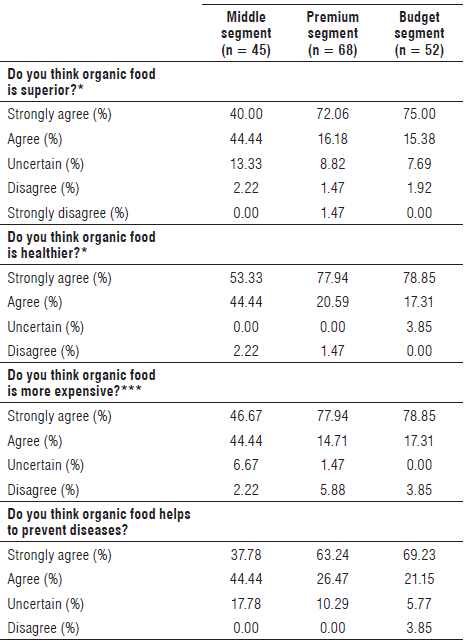

Table 4 shows that more than 80% of the consumers in all segments agreed or strongly agreed that organic food is superior in quality and helps prevent diseases. Likewise, 90% of them considered organics healthier and more expensive than non-organics, similar to the findings of Higuchi and Avadi (2015).

TABLE 4 Perceptions about organics across consumer segments.

Significance levels of 5%, 1%, and 0.1% are indicated by *, **, and ***, respectively. The significance levels of continuous and categorical variables were estimated using an ANOVA and Fisher's test, respectively.

These results indicate that potential farmers and marketers of Andean blackberry should target consumers in the high yielding segments (i.e., premium and medium) in order to profit from their higher WTP. Although most consumers who know organic certifications (51%) are in the medium segment, almost as many in this group do not give much importance to such certification. This contrasts with the case of premium and budget consumers who, despite not having prior knowledge about this credentials system, consider it important for future purchases. Therefore, medium consumers could be targeted as potential buyers of non-certified organic Andean blackberry, whereas the certification could be more significant for the other two segments. This is particularly important considering that many small farmers struggle to get and maintain certifications due to multiple reasons such as the required transition time to become organic, high infrastructure investments, extensive paperwork, and harmful contamination from non-organic neighbor farmers.

As to the implementation of the current results, individually targeting consumer segments in the present context is troublesome due to the existence of common features among them, such as the main place for buying organics, which makes it virtually impossible to address a specific segment through a factor like price. Similar problems have already been reported by Claycamp and Massy (1968). The fact that some groups purchase the product in different shop types (i.e., supermarkets, marketplaces and online shops, the latter mainly used by budget and premium consumers) could be exploited by better targeting consumers. Commercial strategies attempting to reach premium consumers should consider sales at specialized healthy food stores, supported by organic certification, brand promotion and specialized packaging for organic Andean-blackberry. Medium consumers, in turn, could be approached by using fair-trade certification along with information about the benefits of organic Andean blackberry consumption, its place of origin and the environmental benefits of organic production. An alternative certification to be used for medium consumers could be one offered by participatory guarantee systems, which is used by the agroecological markets network of Bogota. Finally, budget consumers could also be reached in more affordable organic product stores such as market places or agroecological markets.