Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Medicas UIS

versión impresa ISSN 0121-0319

Medicas UIS vol.26 no.3 Bicaramanga sep./dic. 2013

Editorial

The Role of Cinema and Television in

People's Perception of Medicine

and Healthcare-related Topics

Adriana Marcela Arenas-Rojas*

*Estudiante VIII Nivel de Medicina. Editora Asociada y Miembro del Consejo Editorial de la Revista MÉDICAS UIS. Facultad de Salud. Universidad Industrial de Santander. Bucaramanga. Santander. Colombia.

Correspondencia: Srita. Adriana Marcela Arenas-Rojas. Apto 130, Bloque 14-20B, Bucarica IV Etapa. Floridablanca. Santander. Colombia. Correo electrónico: adriarenasr@gmail.com.

"Although for some people cinema means something

superficial and glamorous, it is something else. I think

it is the mirror of the world."

Jeanne Moreau

Since their inception, cinema and television have unquestionably transformed the way contemporary society views itself. The screen is a broad canvas on which settings and characters come to life reflecting the changes culture has gone through over the years. Medicine is one of the oldest and most important professions, and has a long history on film and television, being one of the first ones to make it onto the big screen during the inception of cinema at the end of the 19th century1-3.

From Men in White (1934) starring Oscar-winner actor Clark Gable, to Side Effects (2013) starring Oscar-nominated actor Jude Law, the medical profession has never been short of star appeal when it comes to the silver screen. Since the beginning of cinema, there have been several types of movies and portrayals of the medical profession, with early serious and dramatic movies such as Internes Can't Take Money (1937), A Child Is Waiting (1963) and MASH (1970), as well as comedy movies such as Young Doctors in Love (1982) and Bad Medicine (1985). Followed by films like Awakenings (1990), The Doctor (1991), Patch Adams (1998), Wit (2001), Something the Lord Made (2004), and most recently Sicko (2007), Contagion (2011) and Side Effects (2013); all of them with different topics and points of view according to their date of release and culture influence at the time1,4.

When it comes to television, though it may seem that the medical dramas have only been recently popular, in fact they have been around for years. The success of Ben Casey in the 1960s and M.A.S.H. and Marcus Welby, M.D. in the 1970s represented a defining period on the history of television's prime-time medical series. This set a path for a whole new genre in television that was quickly followed by L.A. Law, St. Elsewhere, and Doogie Howser, M.D. in the 1980s; E.R. and Chicago Hope in the 1990s; and most recently Grey's Anatomy and House M.D. in the 2000s5-7.

The portrayal of doctors have changed simultaneously with society and its need for information, going from a cold and distant image of an all-knowing, god-like doctor, known only by the outcome of his patients, to a more human, more vulnerable portrayal, allowing the public to know more about the physician's personal life and the struggles befitting his profession; the archetype of the wounded healer now pervades contemporary culture5,8.

Depictions of healthcare on the media have become increasingly important primary sources of medical information for the general public as well as for physicians-in-training. Some experts on the media suggest that entertainment can be even more successful than news in giving people a sense of institutions such as medicine. A study performed by the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in 2008 demonstrated that more than 80% of medical and nursing students watch television medical dramas, and another study conducted by the University of Western Sydney in 2009 revealed that 94% of 400 polled medical students are regular viewers of medical television shows8,9.

The portrayal of doctors and healthcare in cinema and television is worthy of analysis as its impact on contemporary society is undeniable. Although the medical drama genre can be both entertaining and engaging, its true significance relies on its potential to inform and influence its viewers regarding controversial but important topics3,6.

Probably the most popular medical condition portrayed in cinema and television is cancer. This medical condition is constantly brought up in today's medical dramas such as Grey's Anatomy and House M.D., as well as in television series not related to medicine such as Breaking Bad and Curb Your Enthusiasm. Its popularity in cinema is not different from television, having being displayed from many angles, from a dramatic and serious point of view in films like Stepmom (1998), The Bucket List (2007) and My Sister's Keeper (2009); to a lighter and comedic approach in movies such as Funny People (2009) and 50/50 (2011). There are benefits to be accrued from this trend of depicting cancer in the media, such as: raising awareness of certain types of cancer, reminding the general public of risk factors and preventive measures, and supporting those who have had cancer with the emotional toll of their experience4,7,9-11.

A survey performed in 1999 by the National AIDS Trust in London, UK, found that most British teenagers gained their knowledge on HIV/AIDS from the plight of Mark Fowler, one of the main characters of the well-known English soap opera EastEnders. Another study sponsored the Kaiser Family Foundation showed that 53% of E.R. viewers stated having learned about important health care issues from the show and that 12% have contacted their physician as the result of something they saw on E.R12,13.

With the growing popularity of E.R. came a project developed by the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health in collaboration with NBC: a news series called Following E.R. The main goal of the series was to take advantage of the interest generated by E.R. to disseminate accurate health information to the general public, using a real-world perspective of the medical environment portrayed in E.R., as well as addressing complex political and ethical issues related to health care in the United States14.

People obtain health-related information from mass media more than any source other than health care professionals, and although accurate representations of medical situations on television can be valuable and educational, inaccurate portrayals can engender misinformation. There is evidence that the general public largely base their perceptions about Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) on their experience of the portrayal of CPR in the media. Many films and television shows present exciting cases of CPR, including thoracotomies and defibrillations, often performed in young victims of violence. Unfortunately, these depictions are often different from reality and from what has been reported in medical literature. For example, approximately 75% of cardiac arrest victims on television survive, much more than the 5% who survive in reality. Similarly, traumatic coma victims on television are far more likely to return to normal function than real traumatic coma victims; 89% vs. 7%, respectively14-19.

As a consequence of this, it has been estimated that 96% of Americans exaggerate the potential benefit of CPR and such misinformation can lead to false expectations of medical treatments. Likewise, it can create communication difficulties between patients and providers, given that in order for patients and their families to have informed discussions with medical professionals about CPR, neurologic prognosis and withdrawal of life support after resuscitation from cardiac arrest, they need to have a realistic understanding of the procedure, its risks and the probability of likely benefits15,17,18.

As television and cinema may potentially influence the perceptions of the general public about CPR, it is recommended that they should be perceived not only as mere entertainment but also as a powerful educational tool. Health policymakers and producers should collaborate on using visual media to spread CPR skill, through highly rated medical dramas, popular entertainment programs and highly-acclaimed films; taking responsibility for the accuracy and the implications of the information provided14,16,19.

Another point to consider is that if a majority of patients are learning about CPR from the media, it suggests that physicians are not providing their patients with necessary information to make critical decisions. And instead of putting all the blame on cinema and television makers for failing to portray CPR accurately, particularly in those productions on which in-depth discussions of CPR have taken place, physicians need to make a concerted effort to discuss this difficult topic openly with their patients, as suggested by Neal A. Baer, a Harvard Medical School physician and co-producer of the television show E.R20.

Besides informing, educating and motivating viewers to make choices for healthier and safer lives, medical-related television storylines have brought up attention to little-known or incurable diseases, making people realize the importance of medical research for a cure or a way to prevent conditions such as Huntington's disease, Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, genetically transmitted diseases and other neurodegenerative conditions16,21.

Medical television shows have helped the general public to understand illnesses such as autism, Asperger's disease, obsessive-compulsive disorder, depression, HIV/AIDS, cardiomyopathies, certain types of cancer, some chronic diseases, among others; as well as the effect they have on the person's and family's life. According to several support groups, television shows have helped them deal with the social and emotional implications of the named conditions. As Martin Ledwick, head of Patient Information at Cancer Research UK, told The Lancet Oncology, by remaining sensitive, television writers and producers have helped viewers to understand cancer better, making it seem "more normal, less frightening"12,13.

Cinema and television are very important vehicles for education about health issues because they can facilitate the debating and learning of attitudes in patient care. Depictions of healthcare providers on the media can serve as tools for teaching about professionalism, etiquette and manners to physiciansin- training. Movies and television episodes often provide examples of perplexing ethical issues and inappropriate behaviors that are difficult to discern in real life, which in an educational setting, could help to engage students and residents in discussions of the appropriate management of such situations5,9,21.

An innovative approach called cinemeducation, involves using clips from popular films and television shows in medical education. It was first reported in 1994 and it has been successfully employed in the instruction of different medical areas including psychiatry, family medicine and internal medicine in undergraduate and residency programs. This instrument has become increasingly popular and it has been reported that students are receptive to this teaching method, being mostly used and particularly useful in teaching about specific symptom presentations, therapeutic managements and psychosocial aspects of illnesses, such as patient care, communication skills, breaking bad news, ethical issues and family dynamics22-25.

A fondness for cinema helps developing sensitivity, creativity and expressiveness, which can be highly significant in the practice of medicine, particularly in primary health care, and thus make it possible to enhance the doctor-patient relationship through the details seen on the screen. Doctor-patient communication in medicine is a key area, since successful communication skills are essential to patient care as they directly affect patient satisfaction, adherence to treatment and health outcomes24,26-29.

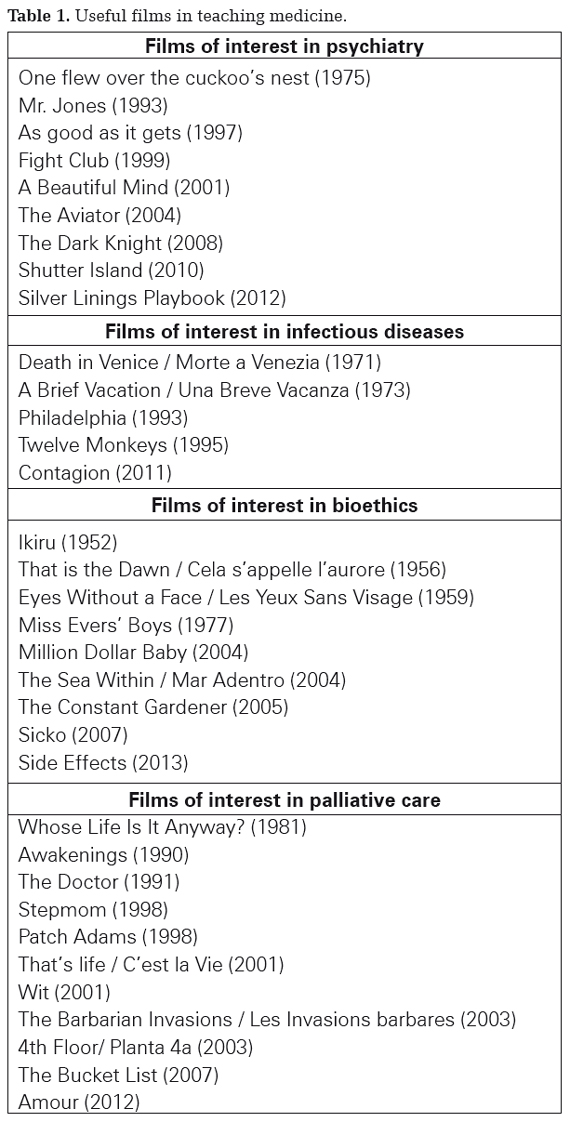

Cinema, as a reflection of human life and its ups and downs, is an indispensable tool for studying those situations that are most transcendental for the human being, such as pain, disease and death. In this sense, the range of films that are useful in medical education is very wide and several compilations of titles and plots have been made, selecting those that portray disease from perspectives that are interesting for teaching (see Table 1)22-33.

It should be noted that cinema and television, however, are not scientific treatises and scripts are not always historically and scientifically accurate, they can have exaggerations and falsehoods, even in films and television shows that do not belong to pure science fiction. If used as an educational instrument, a profound analysis must be made of the approach used in the film or television show regarding diseases and health-related topics, assessing what is close to reality and pointing out which are merely cinematographic devices29,31,32.

Cinema and television are, unquestionably, tools with great impact and with a lot of potential for informing, divulging messages and educating the population, and they can serve enormously in medical training with adequate methodology. Health representatives, physicians and television and film producers should cooperate with each other in using visual media to spread accurate medical knowledge, keeping the entertainment appeal of cinema and television without diffusing inaccurate messages that could misinform the general public. More studies are needed about the influence of cinema and television on people's perception of Medicine and healthrelated topics. In conclusion, it is recommended that cinema and television should be perceived not only as mere entertainment but also as a powerful educational tool7,10,16-33.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to the MÉDICAS UIS Family for these four years of great experiences, friendships and invaluable knowledge, both academic and personal. To the Department of Editorial Possibilities: thanks for all your patience and support. Always keep in mind what has been, unofficially, our motto through all these years of work: we take what we do very seriously, but we have a lot of fun while doing it. Keep on the excellent work, MÉDICAS UIS.

ANNEXES

REFERENCES

1. García JE, Trujillano I, García E. Medicina y cine ¿Por qué? Rev Med Cine. 2005;1:1-2. [ Links ]

2. Turow J. Nurses and doctors in prime time series: The dynamics of depicting professional power. Nurs Outlook. 2012;60(5S):S4-S11. [ Links ]

3. Gross AF, Stern TW, Silverman BC, Stern TA. Portrayals of Professionalism by the Media: Trends in Etiquette and Bedside Manners as Seen on Television. Psychosomatics. 2012;53:452-5. [ Links ]

4. Holmes D. Falling from their pedestal—doctors on film. The Lancet. 2011;377(9780):1825. [ Links ]

5. Tapper EB. Doctors on display: the evolution of television's doctors. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2010;23(4):393-9. [ Links ]

6. Raizman N. Hit and miss—hospital dramas on TV. The Lancet. 2010. 375:1864. [ Links ]

7. Chory-Assad RM, Tamborini R. Television Doctor: An Analysis of Physicians in Fictional and Non-Fictional Television Programs. J Broadcast Electron Media. 2001;45(3):499-521. [ Links ]

8. Shaheen M, Brown A, Huynh V, McNinch D, Jones JS. Not Your Grandmother's Doctor Show: Bioethics and Professionalism in Television Medical Dramas. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(4S):S149. [ Links ]

9. Lepofsky J, Nash S, Kaserman B, Gesler W. I'm not a doctor but I play one on TV: E.R. and the place of contemporary health care in fixing crisis. Health Place. 2006;12:180-94. [ Links ]

10. Barnet E. Dissecting The Medical Drama: A Generic Analysis of Grey's Anatomy and House, M.D. [dissertation]. Boston (MA): Boston College; 2007. [ Links ]

11. Yifan C. Humanity factors and more: A little heads up for medical students and future doctors. Journal of Medical Colleges of PLA. 2013;28:29-31. [ Links ]

12. Burki T. Part I: Cancer in continuing dramas. The Lancet. 2008;9:328-30. [ Links ]

13. Burki T. Part II: Cancer in medical dramas. The Lancet. 2008;9:423-4. [ Links ]

14. Cooper CP, Roter DL, Langlieb AM. Using Enterainment Television to Build a Context for Prevention News Stories. Preventive Medicine. 2000;31:225-31. [ Links ]

15. Brindley PG, Needham C. Positioning prior to endotracheal intubation on a television medical drama: Perhaps life mimics art. Resuscitation. 2009;80(5):604. [ Links ]

16. Harris D, Willoughby H. Resuscitation on television: Realistic or ridiculous? A quantitative observational analysis of the portrayal of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in television medical drama. Resuscitation. 2009;80(11):1275-9. [ Links ]

17. Eisenman A, Stolero J. Can popular TV medical dramas save real life? Med. Hypotheses. 2005;64(4):885. [ Links ]

18. Primack BA, Roberts T, Fine MJ, Dillman FR, Rice KR, Barnato AE. ER vs. ED: A comparison of televised and real-life emergency medicine. J Emerg Med. 2012;43(6):1160-6. [ Links ]

19. Diem SJ, Lantos JD, Tulsky JA. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation on television: Miracles and Misinformation. N Eng J Med. 1996;334(24):1578-82. [ Links ]

20. Baer N. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation on television: Exaggerations and Accusations. N Eng J Med. 1996;334(24):1604-5. [ Links ]

21. Turow J. Television entertainment and the US health-care debate. The Lancet. 1996;347:1240-3. [ Links ]

22. Pappas G, Seitaridis S, Akritidis N, Tsianos E. Infectious Diseases in Cinema: Virus Hunters and Killer Microbes. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2003;37:939-42. [ Links ]

23. Kalra G. Teaching diagnostic approach to a patient through cinema. Epilepsy Behav. 2011;22:571-3. [ Links ]

24. Wong RY, Saber SS, Ma I, Roberts JM. Using television shows to teach communication skills in internal medicine residency. BMC Med Educ. 2009;9:9. [ Links ]

25. Klemenc-Ketis Z, Kersnik J. Using movies to teach professionalism to medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2011;11:60. [ Links ]

26. Gramaglia C, Jona A, Imperatori F, Torre E, Zappegno P. Cinema in the training of psychiatry residents: focus on helping relationships. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13:90. [ Links ]

27. Astudillo W, Mendinueta C. The Cinema in the Teaching of Medicine: Palliative Care and Bioethics. J Med Mov. 2007;1:32-41. [ Links ]

28. García JE, García E. Medicine, Cinema and Education. J Med Mov. 2008;4:39-40. [ Links ]

29. Fresnadillo MJ, Diego C, García E, García JE. Metodología docente para la utilización del cine en la enseñanza de la microbiología médica y las enfermedades infecciosas. Rev Med Cine. 2005;1:17-23. [ Links ]

30. Weber C, Silk H. Movies and Medicine: An Elective Using Film to Reflect on the Patient, Family, and Illness. Fam Med. 2007;39(5):317-9. [ Links ]

31. Prober C, Heath C. Lecture Halls without Lectures - A Proposal for Medical Education. N Eng J Med. 2012;366(18):1657-9. [ Links ]

32. Czarny MJ, Faden RR, Nolan MT, Bodensiek E, Sugarman J. Medical and Nursing Student's Television Viewing Habits: Potential Implications for Bioethics. Am J Bioeth. 2008;8(12):1-8. [ Links ]

33. González P, Garcia DSO, de Benedetto MAC, Moreto G, Roncoletta AFT, Troll T. Cinema for educating global doctors: from emotions to reflection, approaching the complexity of the human being. A Workshop Presentation in Wonca Europe, Basel, 2009. PrimaryCare. 2010;10(3):45-7. [ Links ]