INTRODUCTION

Short stature in children is defined as a height below two standard deviations (-2SD), or under the third percentile for age, gender and appropriate population reference from pubertal stage. This concept should not be confused with poor growth which is defined as a height velocity (cm/year) below two standard deviations from the expected velocity for that age1.

Growth is a very complex process in which a number of features occur only in human being, and some others are common within other species. Fetal growth is the fastest in all human growth phases whose highest peak occurres in the second trimester. Later in childhood growth slows and remains constant until a new peak at puberty. Despite the entire hormonal system is involved in the process of height gain, the Insul - live Growth Factor (IGF) system has one of the lead roles, and it is involved in all phases of human growth2,3.

All this process begins in the hypothalamus where the Growth Hormone Release Hormone is secreted and goes to the adenohypophysis to stimulate the secretion of Growth Hormone (GH), which has an anabolic role in the entire organism by stimulating first the liver, to produce the IGF system; these hormones activate receptors in all the tissues, producing glycogenolysis, lipolysis, rising mitosis rate in epiphyseal growth plate chondrocytes which increases bones size4-5. It has been reported that alteration in IGF’s mice receptors affects normal growing; in IGF-I generated a uterus growth restriction that altered postnatal growth, which reached the 30% of its final height target. Also it was found that abnormal IGF II receptors generated a uterus decrease in size of 40% without modifying postnatal growth2,3,6.

The following review article’s main objective seeks to provide an approach from a health care first level institution, of one of the most frequent queries in paediatrics and general medicine, stunted growth. This is a problem that is frequently seen by the patient’s family as something distressing, height plays an important role in self-esteem and psychosocial development of people, a child who feels that is not growing like his friends or family may bring mood disorders that prevent a properly social, emotional and psychological development7,8.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The relationship of visit to pediatricians or general doctors for stunting in boys versus girls is 1.9:1 being greater the number of visits in boys, however the major growth disturbances occur in girls, who present a higher prevalence of organic pathologies (40%). This allows us to conclude that short stature is being underdiagnosed in girls, most probably because social pressure has imposed that male should be taller than female, therefore short stature in boys result more concerning9.

A population-based survey of growth made on Utah, assessed height and growth speed in nearly 115 000 American children; they found 555 infants with short stature and poor growth rate, but only 5% had an endocrine disorder9. That is a data from a developed country, but short stature is presented very differently on underdeveloped countries, because there is a higher prevalence of malnutrition and other organic causes which are more common than endocrine etiologies.

A retrospective observational study performed in Mexico among 341 children who had been referred to the endocrinologist because of short stature, found out that 45% of the cases had a pathologic etiology, 46% were physiological variants and 9% indicated a normal growth. Also concludes that the average of age at consult was 10 years, and 26% of the patients already were over 12 years and have reached the maximum peak of height velocity10.

A retrospective and descriptive study in Guadalajara (Spain), with children in paediatric consult in the endocrine service, shows that 30.2% of the consult was because of short stature. Majority, 25.5% of these were attributed to Constitutional Delayed of Growth (CDG), 21.4% to Genetic Short Stature (GST) and only 4% to growth hormone deficiency. The 14.5% of the patients were treated with growth hormone. Average age of diagnosis of short stature was 7.3 years, similar in boys and girls11.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We searched and selected articles from PubMed, SciELo, EBSCO HOST, ScienceDirect and UpToDate by using “short stature”, “stature by age”, “growth disorders”, “growth hormone deficiencies”, “bone dysplasia’s and Genetic Short Stature” as searching terms. All the articles found were filtered by language, selecting English and Spanish articles with more than 20 references and those from the last 6 years (the majority), and some others older were took into account because they represented an important source. We chose review articles, original articles and case reports. Also review books were taken into account. We didn’t include meta-analysis and clinical trials.

DISCUSSION

When we see a patient who complains of short stature, a series of questions and measures need to be taken in order to classify the child and determine the diagnosis. Generally, we have two great causes of physiological short stature, GST and CDG. After taking measurements and solve the questions we should be able to classify short stature as pathological or physiological, and this last is sub classified in GST or CDG12,13.

The first question to be inquired is whether in fact the child is stunted or is it just a subjective perception of parents, for this height and age are measured and placed on local height/age tables which is the ideal option; if they are no available WHO ones may be used in infants under five years and over this age CDC tables would be employed14,15. If values match properly, the kid must remain in growth and development control and not being studied for short stature, except if we can determine Height Velocity (HV) below two standard deviations away from the expected for age.

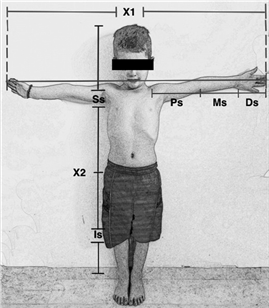

Once the stunting is confirmed, we must determine if it is proportionate or disproportionate. This can be done by measuring and comparing body segments. A useful measure is the wingspan, this is measured with open arms and starts from the third finger of one hand to the opposite one, this magnitude has to coincide with height. Apart from this, different segments dimensions have to be taken; in upper limb to discard pathologies relate to shortening like in rhizomelia (proximal segment), mezomelia (medial segment) or micromelia (distal segment). The inferior segment is measured by taking the distance from the pubic symphysis to the heels, and the superior segment is the result from rest the inferior segment to the height16,17 (See Picture 1). If after obtaining these measurements it is determined that the child has a disproportionate short stature he should be referred to a specialist, whether a geneticist, endocrinologist or orthopedist.

Picture 1: Body’s segments measuresX1= wingspan. X2= Child’s height. X1 must be the same length as X2.Is= from the pubis symphysis to the heels. Ss=X2-Is. Ps= Proximal segment, Ms= Medial segment, Ds= Distal segment.

Observe and consider classic phenotypes of some diseases would be helpful, such as Turner syndrome (short stature women, with retarded puberty or no menarche, irregular cycles without developing of secondary sexual characteristics18,19), Silver Russell syndrome (Short stature, asymmetrical and long face, clinodactyly and asymmetrical limbs20-21), also check the implantation of ears and measure intercantal distance.

If the child has a proportionate short stature it may suggest that we are facing an organic disease or a physiological short stature (GST or CDG) (15. In order to classify the patient into any of these groups, HV must be obtained and placed in the most popular tables from longitudinal growth studies published by Tanner et al. and Prader et al. (20-21. A HV, is traditionally determined at annual or semi-annual intervals, ergo the number of centimeters gained in the last year (cm/year). The measures should be taken in more than two or three times in order to build a HV. If the HV was in a normal percentile but at some point of time is altered and continues later on within this percentile, can lead us to think in organic disease or an endocrine problem that is starting at that moment, and in this case is important to have measurements before the beginning of the disease.

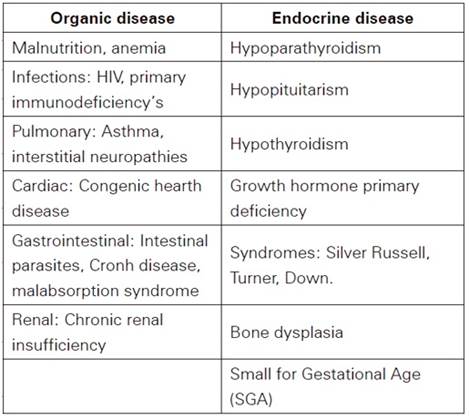

The Body Mass Index (BMI) provides useful information and allows us to differentiate between an endocrine or organic disease. At a higher BMI is more possible an endocrine disease, because most of the times they increase the body fat and interrupt normal growth. In contrast, BMI is lower than the appropriate for the stature when an organic disease is presented, because it causes a loss of body fat in majority of the cases12,20. The principal organic and endocrine diseases that caused short stature are listed in Table 1 21-22.

(23-24-25-26-27)

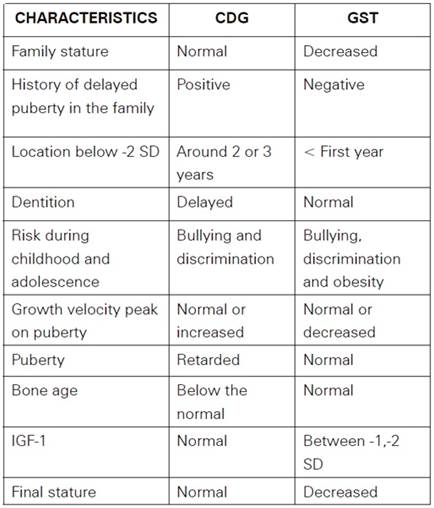

On the other scenario if the patient has presented a steady growth speed but still below the normal measures, we should think and evaluate a CDG or GST, which embrace the 80%10,11 of children with short stature. It’s important to differentiate between these two groups (See table 2), because the final reached stature will vary, and they have different risks during childhood12,14,28-29.

The first important difference is the genetic family stature, it can be taken measuring both parents high and averaging it and adding 6.5cm in males or resting 6.5cm in females, that will be the final genetic stature expected for the child. In CDG final stature will be normal (above -2SD) and in GST will be decreased (below -2SD) (14. Another important parameter is bone age, from a radiograph of the left hand and wrist, which is a measure of skeletal maturation and comparable to real age. This is most commonly determined by the Greulich-Pyle method and it is useful to predict a child’s height potential1,10,11.

It has been said before, the risks of these two groups are different, children with CDG would experience delayed puberty so they may feel themselves different and are more exposed to deal with bullying and discrimination. This is a common thing with GST, but in this case puberty is not retarded. The main difference in these characteristics is that the family of the children with GST may think the infant has not been well fed so they can give a high vitamin supplements diet or more food increasing obesity risk12,29,30.

The onset of the puberty has an important role in the final stature because when it begins before the normal age, under ten and nine years for boys and girls respectively, the HV peak will have a lower duration and the bone age will be affected, that traduces in a final stature decreased. Looking for initial signs of early puberty is very important in these patients, for example, female children with Tanner classification over two or three and with less than eight years, we must think on early puberty and make the reference to an endocrinologist31-32.

When patients with CDG finally reach the puberty, the growth velocity peak will be increased or may be normal, in contrast, those with GST will have a lower velocity peak in puberty31. If we take an x-ray of wrist and hands, those with CDG will have a decreased bone age so they can keep growing for an older age and finally reach a normal stature. That is different from GST, because infants will have a normal bone age, so they will grow until the normal age (15 for girls, 18 for boys) (14,20,31.

One point to remember is that delayed puberty familiar history is only presented in CDG and the child would be located on -2SD at age of two or three, different from GST where the infant is located in -2SD earlier (at first year or before) (31. Also dentition will be delayed in CDG but not in GST.

Another difference between CDG and GST is IGF-1 level, because in CDG is in the normal range but in GST they could be in -1 or -2 SD; findings which confirm the important function of IGF-1 in all growth process, altogether with de Growth Hormone (GH) (3,4,6,29,33-34-35. GH is mainly released at night and in a pulsatile manner; that’s why a basal value it is not useful; few cases need testing of GH and it is request by pediatric endocrinologist if needed but IGF1 should be suitable in primary care9,10,36.

It is very important that the primary care provider understands the physiological variations of growth stunting and knows how to differentiate it from pathological short stature, the first one can be managed and monitored in their level of attention, but pathological must be referred to a specialist in the field. In this review we aimed to provide a new perspective for this problem based on a good clinical history for patients with short stature, the measures and tests required to be taken and finally the manage of the disorder (See Figure 1).

.

CONCLUSIÓN

Short stature is a frequent query in primary care, so it is essential to differentiate physiological variants from pathological, to avoid referring children to Short stature, primary care approach and diagnosis pediatrician or an endocrinologist unnecessarily. There are different variants of physiological short stature that have special features that are important to know and being explained to parents, as they can create false expectations about the final height their children will have. To differentiate physiological from pathological short stature, primary care provider have to know what measures should be taken, to determinate if is a proportionate or disproportionate, and also is essential to understand the meaning of Body Mass Index and Growth Velocity in stunted children. In all this context of pathological short stature, there are a few phenotype characteristics that can guide the diagnosis to a genetic problem. Finally, the primary care provider has to understand the meaning of the different test with growth hormone and when a patient needs one.