Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Cuadernos de Lingüística Hispánica

Print version ISSN 0121-053X

Cuad. linguist. hisp. no.28 Boyacá Jan./Dec. 2016

https://doi.org/10.19053/0121053X.4913

Peer support in small group EFL writing tasks*

Apoyo entre pares en tareas de escritura en inglés en pequeños grupos

Appui entre pairs de petits groupes, en tâches d'écriture en anglais

Apoio entre pares em tarefas de escritura em inglés em pequeños grupos

JESÚS DAVID GUERRA LYONS**

jdguerra@uninorte.edu.co

* Artículo resultado de investigación.

** Licenciado en Humanidades - inglés, Universidad de Córdoba, Montería, Colombia. Magíster en la Enseñanza del Inglés, Universidad del Norte, Barranquilla, Colombia. Docente tiempo completo del Instituto de Idiomas de la Universidad del Norte, Barranquilla - Colombia. Miembro del grupo de investigación Lenguaje y Educación (Colciencias A).

Recepción: 08 de febrero de 2016 Aprobación: 28 de marzo de 2016

Forma de citar este artículo: Guerra Lyons, J.D. (2016). Peer support in small group EFL writing tasks. Cuadernos de Lingüística Hispánica, (28), 149-166. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.19053/0121053X.4913.

Abstract

This paper reports on a classroom-based research study focused on the issue of support in the context of small group writing tasks in an EFL course. The main interest was in analyzing how learners structure different forms of assistance depending on their intersubjective awareness of each other's goals and needs in the task. This structuring of learner support was compared to that of teacher-provided support in order to identify similarities and contrasts. Learners were found to provide at least three types of support: cognitive, strategic and feedback support. In each of these support types, specific intersubjective dynamics are reported to unfold as learners' construed peers' ongoing needs and goals. Teacher support was found to be mostly strategic, that is, mostly oriented towards task performance. Besides, it is suggested that teacher support often mismatches learners' needs due to lack of spaces for establishing intersubjective ground. Pedagogical and research implications are finally discussed.

Key words: intersubjectivity, peer support, small group task, teacher support.

Resumen

Este artículo se basa en una investigación de aula enfocada en la temática del apoyo en tareas de escritura en grupos pequeños al interior de un curso de inglés como lengua extranjera. Se buscó analizar la forma como los aprendices estructuran distintas formas de apoyo según su conciencia intersubjetiva de las necesidades y objetivos de sus pares, las cuales fueron comparadas con las ofrecidas por el docente con el fin de identificar similitudes y contrastes. Se encontró que los aprendices ofrecen al menos tres tipos de apoyo: cognitivo, estratégico y evaluativo. En cada uno de ellos se encontraron dinámicas intersubjetivas particulares a medida que los aprendices interpretaban las necesidades y objetivos que surgían durante la tarea. Se observó que el apoyo del docente fue principalmente estratégico, es decir, orientado al desarrollo de la tarea. Además, se observa que el apoyo del docente a menudo no corresponde con las necesidades de los aprendices debido a una falta de espacios para el establecimiento de terreno intersubjetivo común. Al final se discuten implicaciones pedagógicas e investigativas de estos hallazgos.

Palabras clave: apoyo docente, apoyo por pares, intersubjetividad, tareas en pequeños grupos.

Résumé

Cet article se base sur une recherche dans la salle de classe, focalisée sur la thématique de l'appui en ce qui concerne les tâches d'écriture de petits groupes, à l'intérieur d'un cours d'anglais langue étrangère. On a cherché à analyser la manière comment les apprenants structurent de diverses formes d'appui selon leur conscience intersubjective des besoins et des objectifs de leurs pairs. Ces formes-ci ont été comparées avec celles offertes par l'enseignant ayant l'objectif d'identifier des similitudes et des contrastes. On a trouvé que les apprenants offrent au moins trois types d'appui; cognitif, stratégique et évaluatif. Dans chacun d'entre eux, on a trouvé des dynamiques intersubjectives particulières au fur et à mesure que les apprenants interprétaient les besoins et les objectifs qui surgissaient pendant la tâche. On a observé que l'appui de l'apprenant a été principalement stratégique, c'est-à-dire, orienté vers le développement de la tâche. En plus, on a observé que l'appui de l'enseignant ne correspondait pas souvent aux besoins des apprenants, dû au manque d'espaces pour établir du terrain subjectif commun. A la fin, on discute des implications pédagogiques et de recherche de ces découvertes.

Mots clés: appui enseignant, appui par pairs, intersubjectivité, tâches en petits groupes.

Resumo

Este artigo se baseia em uma pesquisa de sala de aula enfocada na temática do apoio em tarefas de escritura em grupos pequenos ao interior de um curso de inglês como língua estrangeira. Buscou-se analisar a forma como os aprendizes estruturam distintas formas de apoio segundo sua consciência intersubjetiva das necessidades e objetivos de seus pares, as quais foram comparadas com as oferecidas pelo docente com o fim de identificar semelhanças e contrastes. Encontrou-se que os aprendizes oferecem ao menos três tipos de apoio: cognitivo, estratégico e avaliativo. Em cada um deles se encontraram dinâmicas intersubjetivas particulares à medida que os aprendizes interpretavam as necessidades e os objetivos que surgiam durante a tarefa. Observou-se que o apoio do docente foi principalmente estratégico, ou seja, orientado ao desenvolvimento da tarefa. Além disso, se observa que o apoio do docente frequentemente não corresponde com as necessidades dos aprendizes devido a uma falta de espaços para o estabelecimento de terreno intersubjetivo comum. No final se discutem implicaçôes pedagógicas e de pesquisa destes resultados.

Palavras chave: apoio docente, apoio por pares, intersubjetividade, tarefas em pequenos grupos.

Introduction

Modern educational literature recognizes peers as key participants in human learning, an argument which has been supported from a number of theoretical perspectives (Werstch, 1979). Since Vygotsky's claim that learning occurs first in interaction with others and later as internalized thinking processes, numerous studies have attempted to describe the role played by peer interaction in the construction of zones of proximal development. One of the major claims has been the observation that learners can provide each other with a wealth of learning opportunities, among which count the possibility to receive elaborated feedback (Webb, 1989) and achieve higher conceptual understanding (Webb & Kenderski, 1984).

In second language acquisition, peer interaction in small groups has also stirred much interest from researchers. Interaction between learners has been found to integrate linguistic, cognitive and social dimensions of communication. As Swain and Lapkin (2001) point out, learner/learner interaction is a space where "language use and language learning can co-occur. It is language use mediating language learning. It is cognitive activity and it is social activity" (p. 7).

Sociocultural and interactionist claims for peer interaction have resonated into second language writing pedagogy, giving rise to the collaborative writing movement. Research has shown that, when writing texts together, learners are able to focus feedback on lexical, grammatical and discourse aspects (Donato, 1994; DiCamilla & Anton, 2012; Storch, 2005). Joint writing has also been associated with higher propositional quality in final products, due to the fact that learners engage in explaining their viewpoints to peers before writing, which leads to an enhanced sense of audience (Higgins, Flower & Petraglia, 1992; Keys, 1994). Donato's (1994) notion of "collective scaffolding" provides further rationale for promoting writing in groups. According to him, when working collaboratively on a writing task, a pool of collective language resources becomes available for group members to use.

The concept of support is closely linked to the rationale thus far exposed. Support refers to the assistance provided by a relatively more capable peer which is oriented towards enhanced performance or problem solving (Vygotsky, 1978). Not only do teachers offer support, but so do learners to one another (Donato, 1994), a phenomenon that could be explained from the notion of intersubjectrvity.

Intersubjectivity refers to the condition between two or more human beings of having a common mental ground on which cognitive, affective and communicative actions can be coordinated (Swain, Kinnear & Steinmann, 2011). Sociocultural theory has drawn upon this concept to investigate learning in interaction), using it to explain why certain instances of interaction succeed at promoting learning, while others do not (Werstch, 1979; Lantolf & Thorne, 2006). The lack of the cognitive and affective connection created in intersubjectivity has been found to trouble shared construction of knowledge among task participants, mainly because of possessing different mental frames, different objectives and conflicting views on task performance (Lantolf, 2006). Thus, in analyzing learner support and contrasting it to teacher support, the concept of intersubjectivity provides a deeper layer of analysis through which interactional moves can be interpreted.

In developmental psychology, intersubjectivity has been classified into primary, secondary and tertiary intersubjectivity. Primary intersubjectivity operates mostly at the affective level (Trevarthen, 1979), and it is defined as awareness of peers' subjective states (doubt, frustration, confidence, achievement, etc.). Such awareness relies on non-verbal clues in early childhood (gestures, behaviors), but in later development, it is also expressed through affective language, which may be direct (I'm feeling frustrated) or indirect. In indirect expression, the interlocutor may need to infer the affective intent of the proposition according to the ongoing social context.

Secondary intersubjectivity refers to the recognition of interlocutors' goals and intentions, which may also be directly expressed, such as in I want to complete this exercise or indirectly expressed, as in It would be nice if we could get this done quickly. Finally, tertiary intersubjectivity entails awareness of interlocutors' ways of thinking (beliefs, values, world representations, concepts), which are informed either explicitly or signaled implicitly (Matusov, 2001; Tomasello, Kruger & Ratner, 1993). These three forms of intersubjectivity account for what has been denominated "perspective-taking", or the ability to assume reality from the perspective of others (alterocentric positioning).

Intersubjectivity has also been extensively studied and described in different fields of linguistics. In cognitive linguistics, it is defined as the mental coordination of subjective states between individuals, in which shared representations aid in creating a common awareness of the reality at hand (Verhagen, 2005). Cognitive functional linguistics analyzes the intersubjective interface between subject and text, tracking down interpersonal enactments which indicate intersubjective positioning (Traugott, 2010). Systemic Functional linguistics investigates intersubjectivity at the text level, analyzing how lexicogrammatical systems (such as modality, theme and polarity) and discourse semantic systems (engagement, attitude) construe the perspective of others (Martin & White, 2005).

This paper sets out to analyze the support learners provide to one another in small group writing tasks in order to describe the extent to which such support relies on intersubjective awareness. Although it may be argued that all support is by nature intersubjective, I propose that certain kinds of support reflect a deeper awareness of interlocutors' affective, motivational and cognitive states. I also suggest that these higher forms of intersubjectivity are favored by symmetrical positioning of the kind that emerges between peers during joint task performance.

1. Methodology

In Stake's (1995) terms, this study can be classified as an instrumental case study in that it serves to explore a phenomenon (support) within a particular community in order to understand it more deeply. The community, in this case, corresponds to an English 6 course at Universidad del Norte, in the Caribbean coast of Colombia. This course is included within an 8 level skills-based English program which most undergraduate students take as part of their professional training, and which is aimed towards reaching B2 level of competence. The specific section of the course observed focused on academic writing and its goal was for students to write compare and contrast essays. The writing unit thus featured an essay model, explicit teaching of essay features and a practice stage, in which learners had to write a joint essay. It is in this stage that most of observation took place, considering the study's main aim of analyzing peer support during small group tasks.

Data collection was conducted through non-participant classroom observation aided by audio recording, stimulated recall and an interview to the teacher. In observation, the main purpose was to obtain authentic samples of learners' interaction while carrying out the practice stage. The researcher thus placed audio recorders amidst 3 groups of 4 students each and remained in the background making notes of relevant observable behavior. After observation, specific students were chosen to participate in stimulated recalls, which were oriented towards eliciting their interpretations of their own interaction. This data collection technique offers unique ways to triangulate findings in qualitative research (Richards, 2003). Finally, an interview to the teacher took place featuring key findings in observational and stimulated recall data.

Data analysis proceeded as suggested by grounded theory research. Audio recordings were transcribed and the resulting turns were assigned codes depending on their interactional function (guiding, questioning, facilitating). These codes were gathered into larger categories depending on the type of support offered. Three main categories emerged: cognitive, strategic and feedback support. Later, analysis focused on the intersubjective processes through which support was negotiated between learners and in teacher-student interaction. This led to a contrast of interactional features for offering support in peer interaction and teacher-student interaction.

2. Analysis

2.1 Emerging categories

In regard to the dimension of task performance addressed by the supporting intervention, three types of support were identified: cognitive, strategic and feedback support. Cognitive support focuses on concept construction through characterization, definition, demonstration, argumentation or exposition of facts. Strategic support focuses on the how-to of the task, that is, in the choice of adequate procedures in regard to task purpose. Feedback support refers to learners' need of receiving ongoing assessments of their performance as they strive to complete the task successfully.

Concerning the degree to which the support offered suggests intersubjective awareness, each of the three support types is described as highly intersubjective or partially intersubjective. Highly intersubjective support is that in which there is evidence of supporters' engagement with peers' affective or mental states. This can be seen in actions such as exchanging questions, considering alternative viewpoints, expressing agreement or disagreement, describing and reacting to affective states and expressing goals or motivations. In partially intersubjective support, the supporter is mostly unilateral, thus preventing a fluid exchange of ideas and affective reactions. This is evidenced in monologic speech, use of high modality (have to, need to), fixed question-answer scripts and negative polarity (no, don't, none).

Finally, for each exchange, the alignment between interlocutors is categorized as symmetrical, when individuals position themselves as equals, or asymmetrical, when of the participants is construed as possessing higher authority.

2.2 Cognitive support

The need for cognitive support mainly arose from the conceptualization of the types of medicine which constituted the content of the writing products. Activity 1, for example, required participants to compare and contrast two types of medicine in a short expositive essay. The types of medicine involved did not bear clear-cut differences, which led to confusion in some of the participants. However, participants were usually ready to mediate their peers' conceptualizations once difficulties were sensed.

In Excerpt 1, an example of highly intersubjective symmetrical cognitive support is presented. This exchange occurred at the beginning of the activity, when learners were starting to make sense of the task conditions and the task content at hand. The task required learners to produce an outline of a compare and contrast essay in which two types of medicine described in one of the textbook readings were compared.

The supportive exchange starts when Lucia1 inquires Christian on the two types of medicine he is going to compare and contrast in his outline (Turn 51). Christian had already started his outline after receiving teacher mediation on the concepts to be compared. Lucia, on the other hand, was still hesitant about the type of comparison she was going to make. Right after that, Christian attempts to support Lucia on her identification of the differences by using some of the mediation previously received from the teacher. However, Lucia seems more interested in using Christian's already produced comparison as a model to guide hers (Turn 55). She then takes a closer look at Christian's work and remarks on some of its flaws humorously (Turn 62). Her comments make Christian feel the need of defending his product from Lucia's humorous though critical stance.

The above exchange implies an intersubjective cognitive mediation considering the symmetrical positioning in which both participants manifest a genuine interest in assisting each other's thinking processes. Use of humor in Lucia's critical remarks and understanding of these as humorous by Christian reveals both an affective connection (primary intersubjectivity) and comprehension of each other's goal-oriented actions (secondary intersubjectivity). In a similar vein, Excerpt 2 below shows how intersubjective cognitive support is mutually constructed:

What concerns the participants in the previous excerpt is jointly conceptualizing and appraising the types of medicine which constitute the task content. They are jointly attempting to identify the characteristics of chiropractic medicine, using the textbook as mediation. In Turn 35, Lucas provides a verbalization from the description of chiropractic medicine given in the textbook, focusing on its goal. Francisco appraises the content of Lucas' verbalization as interesting. However, for Lucas, this conceptualization does not seem to match task requirements (Turn 36), and he decides to sound out Francisco's interpretation. It seems that, for Lucas, the mediation from the book added to his own conceptualization was not enough. He wished to engage Francisco as a thinking partner.

Thus far, intersubjective cognitive support has been explored within the conceptual aspect. Another form of cognitive support traced in the observed activities is linguistic support. This form of support can be considered intersubjective in that participants need to be able to read the other's level of understanding in order to provide the appropriate form of support. In excerpt 2, this is illustrated:

The previous excerpt shows linguistic support being offered to one of the participants on the spelling of the word "similarities". The exchange starts with C making a direct call for support (turn 71), which meets M's immediate answer. It becomes clear, however, that M's support does not fulfill the initial request, which was focused on the orthographical aspect (turn 72). L's revoicing of C's question also shows that this participant had been entertaining the same doubt. L asks to be shown the word written, as he strives to rehearse the spelling aloud. C joins L in his spell aloud strategy (turn 75). L eventually manages to pronounce the word completely, and proceeds to offer more explicit support in face of C's persistent inability. This more explicit support comes in the form of syllabic division of the word. C seems to have mentally represented the spelling and contrasted it with a different mental representation, as evidenced in his counter-expectational question (Really?) (turn 78). Noticing C's disbelief, L moves one step farther in the supportive scale by showing the problematic word written. C continues comparing the presented spelling with his initial mental representation, to which L responds with further assistance in noticing the actual form. The supportive exchange does not, nevertheless, lead to C's being able to reproduce the word, at least not aloud. L still ends his reproduction attempt with a hispanicized ending of the word (tl-Es) (turn 83).

In excerpt 3 next, an episode of teacher-mediated cognitive support can be observed. In this excerpt, Christian turns to the teacher for help in distinguishing the differences between the types of medicine involved. Before, he had tried to agree with his group members on a distinction, but no consensus was reached. During the exchange, it is possible to observe how Lucia, who had previously sustained disagreement with Christian, now assists him in putting his doubt forward to the teacher (Turns 21,23,32).

This support could be considered partially intersubjective, first, because the teacher did not take the time to find out Carlos's goal in understanding the differences mentioned. In turn 29, she actually dismisses his plan of comparing biomedical and homeopathic medicine and suggests him to compare others. The exchange is directive, though modalized (I would suggest that...), and the teacher speaks in rather long turns (Turns 33, 35).

Looking at the exchange more closely, it is possible to notice how the teacher interprets Christian's as a request for strategic support. In Turns 29 and 33, her mediation focuses more on what to do, rather than on the concept itself. It is possible that the students' request for support was not clearly posed due to linguistic limitations. As a result of this, Christian's evaluation of teacher support in the stimulated recall was negative:

"Perhaps the teacher didn't explain well... I mean, she didn't totally clear out the doubt we had. So we kept on with the same misunderstanding, but then, we didn't want to call the teacher again to explain something we didn't understand.

It could be said that Christian and the teacher did not succeed in creating sufficient intersubjective ground as to share the same conceptions, or for Christian to guide the teacher's support towards his actual doubt.

Strategic Support

Support addressed to mediate the actions of others in the context of writing activity was also analyzed in the observed lessons. Similarly as cognitive support, differences were identified in the way the teacher and peers offered strategic support. In excerpt 4, an instance of peer-derived strategic support can be observed:

In Excerpt 4, the participants are involved in a mutual effort to make sense of the task conditions (submission and product). One of the features of this exchange is the uncertainty of the language used in the exchange. In turn 38, Lucía uses mental self-projections (creo, estoy confundida, supongo) to denote the interpretive nature of her support. Despite her uncertainty, she still offers support (she might as well have said she did not know), which shows that she wished to maintain intersubjectivity rather than to guide Christian's actions. Another feature is the projection of teacher's earlier strategic guidance (Turn 39), upon which students base their interpretations. In Turn 40, one of the student reports her own actions as an indirect form of strategic support. In the end, participants' uncertainties add up to form a rather certain conclusion regarding task deadline and product. This mutually constructed strategic support differs from the teacher-derived strategic support seen in excerpt 5:

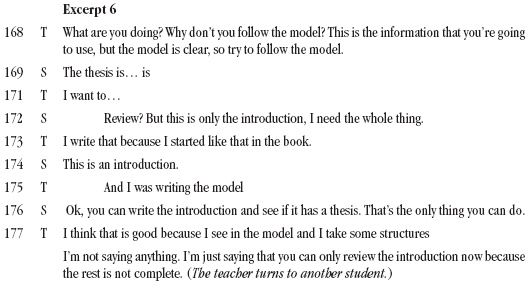

Unlike the peer-derived strategic support in Excerpt 4, the teacher in Excerpt 5 is quite directive. This is evidenced in the use of direct questioning in Turn 168, interruption in turn 171 and restrictive modality in Turn 175. The exchange starts when the teacher notices the student drifting off the pedagogical agenda set for the class, part of which involved use of a model to guide writing. Despite the student's claims of following the model, the teacher addresses the student's attention towards a specific problematic area (not including a thesis statement in his introduction). The student, however, interprets this is an evaluative intervention, as seen in his counter appraisal of his work as good (Turn 176).

2.3 Feedback support

Learners often feel the need of their performance being assessed on an ongoing basis prior to submission of their final product. This represents a distinct form of support, here named feedback support. In Excerpt 6, feedback support being exchanged during a joint writing task can be observed:

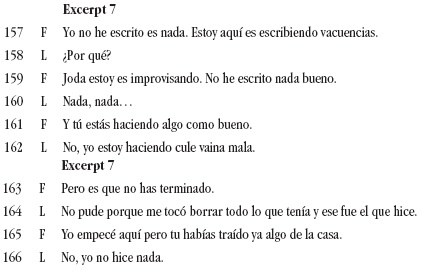

In Excerpt 6, Francisco and Lucas, who had been working jointly in producing their own draft of a compare and contrast essay, engage in mutually assessing what they had written so far. Francisco is quite critical about his own product. He assesses it as insufficient and improvised, based on the fact that he had not prepared anything in advance. Alternatively, he appraises his peer's product as good enough. The subjective state inscribed in Francisco's appreciation is probably frustration at not being able to produce a satisfactory draft. Lukas seems to have become aware of Francisco's state of frustration, for which he decides to speak self-derogatorily of his own work as well. By doing this, Lucas is able to maintain primary intersubjectivity with his peer. Knowing that his peer does not consider his work good enough might give Francisco a way to gauge the quality of his own work. Feedback support in SS joint activity interaction is thus reflective and comparative. Teacher feedback support, on the other hand, relies more on the teacher's criteria for task quality, as seen in Excerpt 7:

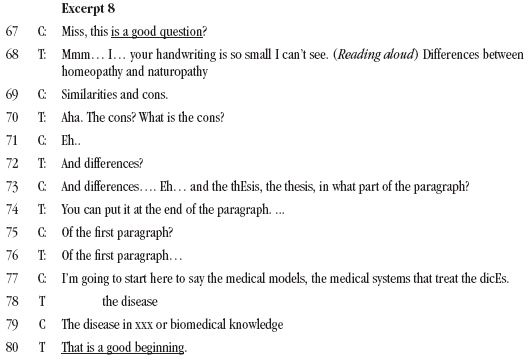

Christian. amidst writing the introduction for his essay. appeals the teacher to provide feedback support for his writing. The teacher inquires further into the students' writing procedure. attempting to understand what he means by cons. In turn 77. the student requests feedback support for his procedure. which he receives in turn 80. In both instances of feedback support. it was the teacher who decided what was good and what was not. This contrasts with the comparative forms of peer assessment seen in Excerpt 6. It could be argued. however. that feedback support of a more direct type as in Excerpt 7 is what learners expect to receive.

3. Discussion

One of the running issues in this exploration has been learners' ability to provide complex forms of support based on their capacity for intersubjective thinking. These forms of support. classified here within the cognitive. strategic and feedback realms; have been shown to differ from teacher-mediated forms of support. This difference has been observed to lie mostly in the asymmetrical intersubjective positioning which emerges in most classroom-based teacher-student interaction. Student-student interaction has. on the other hand. been observed to lead to more symmetrical. participative and interpretive support. Similar findings are reported in Donato (1994). who observes that learners are able to collectively make up for one another's lacks by contributing to the available knowledge pool.

The analyzed exchanges show that. by relying on their intersubjective capacity. participants are able to provide varying degrees of explicitness in their support. much as described in dynamic assessment (Van Compernolle. 2011). What can be observed is a sequence of different forms of support. each leading to a narrowing of the attentional focus and a gradual reduction in the level of difficulty of the "novice's" response (as also found by Davin & Donato. 2013). This provides evidence that are learners not only able to give fine-tuned support to a less knowledgeable peer. but they are also capable of transferring forms of support originated in their own heuristic competency-building efforts. In other words. learners are able to support others with forms of mediation that have worked for themselves.

These forms of mediational transfer show that support given by peers in the context of joint activity can sometimes be more fluid and meaningful than other forms of mediation (e.g. teacher mediation). In the case of teacher mediation. it has been observed that the strategic. cognitive and feedback support provided is often more direct than peers' support (Aljaafreh & Lantolf. 1994). At the moment of being called into the activity. the teacher usually lacks the background of the activity circumstances which led to a particula difficulty. being the learner's job to acquaint the teacher into this background . that is. to build an intersubjective context from which adequate support can be provided. However. as observed in some of the analyzed excerpts. the construction of intersubjective ground between students and the teacher can sometimes be troubled by different factors. such as the teacher having a preconceived idea of the needed support or a stereotype of the learner. the student being conditioned to view the teacher as an authoritative voice (rather than as a thinking partner). and the students' linguistic limitation at the time of asking for support. To overcome these potential barriers to intersubjective supportive interaction. teachers might wish to allow time for learners to clearly shape the background of the difficulty. and to build the sufficient rapport as to lead the teacher's support in the intended direction. In other words. for adequate supportive intervention. there needs to be a disposition to create a shared mental space with the learner.

Conclusions

The analysis and discussion here presented have attempted to characterize support in student-student joint activity interaction. The fact that students are capable of providing each other with complex forms of support. homologous to those in teacher-student interaction. has been emphasized. This support has been shown to go beyond the linguistic realm. to encompass cognitive. strategic and feedback support. Likewise. some key distinctions between peer and teacher-derived support have been outlined. featuring different levels of symmetry. certainty and intersubjective positioning. It has been suggested that. whereas teacher's support is more task-oriented. peers' support is more intersubjectively constructed. Despite these distinctions. both forms of support are considered valuable for learning during group activity.

Exploration of the observed lessons from a sociocultural perspective. more specifically though the lens of intersubjective activity construction. has allowed a refreshed view of student-student interaction in the context of undergraduate EFL group activity. It has made visible otherwise taken-for-granted issues in learners' collaborative dialogue. such as the role of primary. secondary and tertiary intersubjectivity in developing supportive interaction. In a larger sense. sociocultural concepts interwoven in this study (such as mediation. collaboration and activity) have afforded a wider representation of language learning. communication and interaction. Under such traditional conceptual frameworks as the acquisition model of language learning and the conduit metaphor of communication. much of the richness of meaning in group activity can boil down to discrete linguistic phenomena. leaving out the whole social and cultural context which shapes language learning. Without denying the usefulness of those frameworks. sociocultural theory could be considered a more accurate model of how language learning works in a social context. such as the classroom.

Indeed. there are limitations in this study. foremost of which is the fact that the observations were limited to a specific group of learners for a limited span of time. For more reliable and valid conclusions to be reached. further observation in various contexts for longer periods of time might be necessary. An interesting line of research would be the exploration of how supportive intersubjectivity evolves throughout coursework. focusing on changes in student-student and teacher-student support at different stages and for different language skills.

References

Aljaafreh. A.. & Lantolf. J.P. (1994). Negative feedback as regulation and second language learning in the zone of proximal development. The Modern Language Journal. 78. 465-483. [ Links ]

Davin. K.J.. & Donato. R. (2013). Student collaboration and teacher-directed classroom dynamic assessment: A complementary pairing. Foreign Language Annals. doi: 10.1111/flan.12012. [ Links ]

DiCamilla. F. J.. & Anton. M. (2012). Functions of L1 in the collaborative interaction of beginning and advanced second language learners. International Journal of Applied Linguistics. 22. 160-188. [ Links ]

Donato. R. ( 1994). Collective scaffolding in second language learning. In J. P. Lantolf & G. Appel (Eds.). Vygotskian approaches to second language research (pp. 33-56). Norwood. NJ: Abblex. [ Links ]

Higgins. L.. Flower. L. & Petraglia. J. (1992). Planning text together. The role of critical reflection in student collaboration. Written Communication, 9(1). 48-84. [ Links ]

Keys. C.W. (1994). The development of scientific reasoning skills in conjunction with collaborative assessments. An interpretive study of 6-9th grade students. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 3(9). 1003-1022. [ Links ]

Lantolf. J.. & Thorne. S. (2006). Sociocultural theory and the genesis of second language development. Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Lantolf. J. (Ed.) (2000). Sociocultural theory and second language learning. Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Martin. J.. & White. P. (2005). The language of evaluation. New York. NY: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Matusov. E. (2001). Intersubjectivity as a means of informing teaching design for a community of learners classroom. Teacher and Teacher Training, 17(2001). 383-402. [ Links ]

Richards, K. (2003). Qualitative inquiry in TESOL. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Stake, R. (1995). The art of case study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Storch, N. (2005). Collaborative writing: Product, process, and students' reflections. Journal of Second Language Writing, 14, 153-173. [ Links ]

Swain, M., & Lapkin, S. (2001). Focus on form through collaborative dialogue: Exploring task effects. In M. Bygate, P. Skehan & M. Swain (Eds.). Researching Pedagogic Tasks. Second Language Learning, Teaching and Testing (pp. 99-118). Harlow: Longman. [ Links ]

Swain, M., Kinnear, P., & Steinman, L. (2011). Sociocultural theory in second language education. Multilingual Matters. [ Links ]

Tomasello, M., Kruger, A., & Ratner, H. (1993). Cultural learning. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 12, 120-134. [ Links ]

Traugott, E. (2010). (Inter)subjectivity and (inter)subjectification. In K. Davidse, L. Vandelanotte & H. Cuyckens (Eds.). Subjectification, Intersubjectification and Grammaticalization. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 29-71. [ Links ]

Trevarthen, C. (1979). Communication and cooperation in early infancy: A description of primary intersubjectivity. In M. Bullowa (Ed.). Before speech: The beginning of interpersonal communication. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Van Compernolle, R. (2011). Developing second language sociopragmatic knowledge through concept-based instruction: a microgenetic case study. Journal of Pragmatics, 17, 1-17. [ Links ]

Verhagen, A. (2005). Constructions of intersubjectivity: discourse, syntax and cognition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society. The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, M.A: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Webb, N. (1989). Peer interaction and learning in small groups. International Journal of Educational Research, 13, 21-40. [ Links ]

Webb, N. M., & Kenderski. C. M. (1984). Student interaction and learning in small group and whole class settings. In P. L. Peterson, L. C. Wilkinson & M. Hallinan (Eds.). The social context construction: Group organization and group processes (pp. 153-170). New York: Academic Press. [ Links ]

Wertsch, J. V. (1979). From social interaction to higher psychological processes. Human Development, 22, 1-22. [ Links ]