I. INTRODUCTION

Foundations are essential for any infrastructure project [1] which must comply with safety regulations while maintaining a balance between service life and budget restrictions as well as environmental factors and imposed design rules. One of the most important elements in a proper foundation is the stratification of the ground beneath the foundation. Poor characterizations of the ground can lead to increased stresses which may result in failure due to general shear failure [2-3]. Most of the calculations described in previous theories consider soil to be homogeneous [4] while disregarding its heterogeneity and providing results which may be unexpected in the field. As a result, this study evaluates the load bearing capacity [5] in stratified soils (two strata) [6, 7-8] using a comparison between three current analytical methods and results from numerical modeling. The analytical methods utilized in the study included Terzaghi [9], Average imaginary foundation [10], and the average parameter method (APM) [11], which differ considerably in their results. As a result, the results obtained will be compared to numerical modeling using the finite element method [12, 13-14] which is obtained when the Prandtl fault surface is formed by increments in controlled displacement.

Numerical modeling is a widely used and studied method applied to engineering foundations as seen in: [12, 18-19]. It is also accepted as a design methodology in some countries including Colombia with its building construction standard: NSR-10. In the finite element modeling of this study, different variables (modulus of elasticity, displacement depth, and displacement-load) were parameterized and two behavioral laws were evaluated (Elastic, Drucker-Prager). These behavioral laws were used to identify the parameters that have the most influence on the calculation of a shallow foundation [15]. Additionally, their insight can be extended to other fields since all infrastructure work requires a foundation providing significant benefits and savings which will generate positive impacts on both the economy and on the safety of the structures.

II. METHODOLOGY

The methodology used in this research study is mainly characterized by using models generated in the Abaqus [16] program and analytical calculations of load capacity. Three load capacity methodologies for stratified soils were chosen: APM, Terzaghi's method, and imaginary footing. These methodologies were chosen since they are the best known and most commonly applied methods in engineering.

The study utilized the General Static Load Carrying Capacity (GSLCC) for each stratum. The soil of each stratum was also modeled using finite element modeling in Abaqus while modifying yield stress [17]. The load capacity in stratified soils (two strata) was found using analytical methods, APM, imaginary footing, and Terzaghi’s method and then calculated using the elastoplastic behavior law and applying the Drucker Prager method [18].

The soil thicknesses utilized in the study was e=0.15m and e=0.5m while taking into consideration that a thickness below 1m results in a greater probability of the formation of the Prandtl fault [19] which will be used as a point of reference between the analytical and numerical methods.

It is important to note that the ideal values of yield stress are taken from the numerical models carried out using one stratum modeled against two strata. The initial condition resulted in the cohesion in soils of one stratum and two strata being null for both cases Df=0m and Df=0.5m. In the case of Df=0.5m and e=0.15m the foundation will be offset in a similar manner. The data from the thickness of the soil layer using analytical methods was not taken into account since it would result in an overload in the numerical modeling.

A. Methodology for Soil of a Stratum

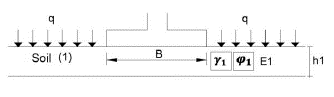

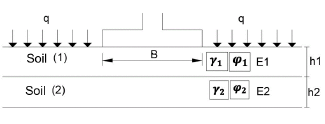

The analytical methods used to evaluate the soil of a stratum model are shown in (Figure 1) while the two-strata model is shown in (Figure 2).

In Table 1 the data used to modify the model of one stratum and two strata with their respective nomenclatures are shown.

Table 1 Parameterized data.

| Nomenclature for the stratum | Nomenclature for two strata | Module [Mpa] | Friction angle [°] |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | E1 | 9.375 | 23.22 |

| B | E2 | 12.5 | 28.42 |

| C | E3 | 25 | 40.1 |

| D | E4 | 50 | 54.12 |

To create the Drucker Prager elastoplastic model in the finite element program, the following input variables are needed as shown in Table 2.

B. Methodology for Stratified Soil (2 Strata)

Simulations with fine soils on top of thick soils and coarse soils on top of fine soils used the following combinations (Table 3).

III. RESULTS AND ANALYSIS

The results from the analytical and numerical methods are presented below.

A. Soil of a Stratum

The results of the calculations performed using the numerical and analytical method are presented for a stratum which was modified by yield stress.

1) Calculation of Load Capacity, Df=0 m, e=0.15 m. The results from the load capacity calculations using the analytical method of the GSLCC and numerical modeling with finite element software, are presented in Table 4.

Table 4 Summary of results modifying the yield stress, Df=0 m, e=0.15 m.

| DATA | Drucker Prager Hardening | qu, [kPa] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | U displacement [m] | Angle of dilation [°] | Friction angle [°] | Yield stress [Pa] | Abs Plastic Strain | Abaqus | GSLCC |

| A | 0.015 | -6.78 | 23.22 | 11984 | 0 | 57 | 43 |

| B | 0.015 | -1.58 | 28.42 | 25172 | 122 | 91 | |

| C | 0.015 | 10.1 | 40.1 | 118271 | 583 | 568 | |

| D | 0.042 | 24.12 | 54.12 | 8637904 | 11609 | 10365 | |

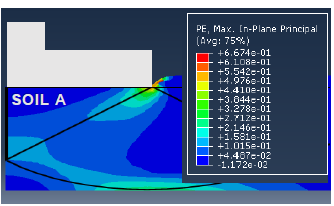

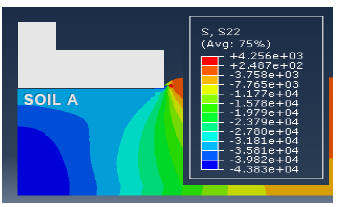

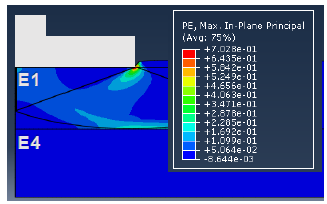

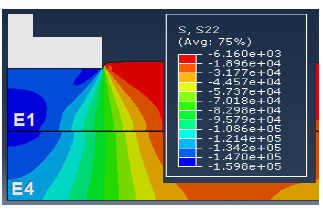

The graphical results obtained from entering the model into the finite element software are shown in Fig. 3. The contour diagram of the plastic deformations (PE) is shown in Fig. 4 and includes a contour diagram of vertical forces. Both Figure 3 and 4 correspond to Soil A, with Df=0 m and e=0.5 m.

2) Calculation of Load Capacity, Df = 0 m, e = 0.5 m. The results of load capacity when modifying the yield stress with Df=0 m and e=0.5 m are presented in Table 5.

Table 5 Summary of results modifying the yield stress, Df=0 m, e=0.5 m.

| DATA | Drucker Prager Hardening | qu [kPa] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | U displacement [m] | Angle of dilation [°] | Friction angle [°] | Yield stress [Pa] | Abs Plastic Strain | Abaqus | GSLCC |

| A | 0.05 | -6.78 | 23.22 | 11984 | 0 | 44 | 43 |

| B | 0.05 | -1.58 | 28.42 | 25172 | 95 | 91 | |

| C | 0.05 | 10.1 | 40.1 | 189234 | 584 | 568 | |

| D | 0.08 | 24.12 | 54.12 | 8637904 | 10703 | 10365 | |

3) Calculation of Load Capacity, Df=0.5 m, e=0.15 m. The load capacity results from the numerical and analytical modeling are presented with a depth of displacement of Df=0.5 m, and a thickness of e=0.15 as shown in Table 6.

Table 6 Summary of results modifying the yield stress, Df=0.5 m, e=0.15 m.

| DATA | Drucker Prager Hardening | qu [kPa] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | U displacement [m] | Angle of dilation [°] | Friction angle [°] | Yield stress [Pa] | Abs Plastic Strain | Abaqus | GSLCC |

| A | 0.015 | -6.78 | 23.22 | 36802 | 0 | 172 | 168 |

| B | 0.015 | -1.58 | 28.42 | 70520 | 330 | 323 | |

| C | 0.015 | 10.1 | 40.1 | 499826 | 1810 | 1696 | |

| D | 0.0254 | 24.12 | 54.12 | 2351551 | 22473 | 25971 | |

4) Calculation of Load Capacity, Df=0.5 m, e=0.5 m. The load capacity results from the values Df=0.5 m and e=0.5 m obtained from the numerical and analytical comparison are shown in Table 7.

Table 7 Summary of results modifying the yield stress, Df=0.5 m, e=0.15 m.

| DATA | Drucker Prager Hardening | qu [kPa] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | U displacement [m] | Angle of dilation [°] | Friction angle [°] | Yield stress [Pa] | Abs Plastic Strain | Abaqus | GSLCC |

| A | 0.05 | -6.78 | 23.22 | 49070 | 0 | 180 | 168 |

| B | 0.05 | -1.58 | 28.42 | 94026 | 346 | 323 | |

| C | 0.04 | 10.1 | 40.1 | 749738 | 1629 | 1696 | |

| D | 0.2 | 24.12 | 54.12 | 11757757 | 24530 | 25971 | |

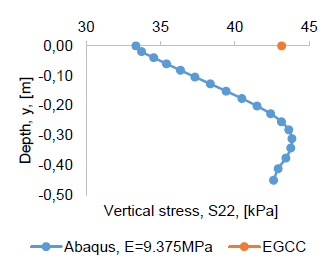

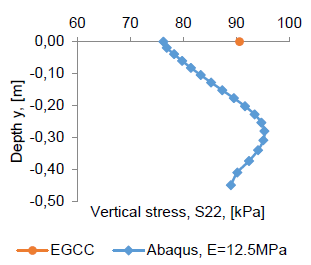

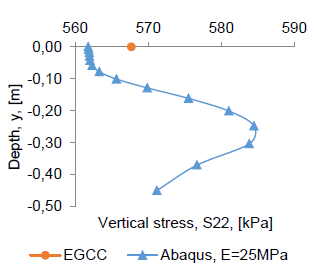

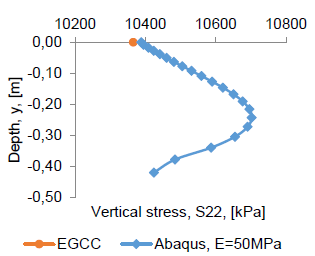

Figures 5 to 8 show the results from the GSLCC and numerical modeling while considering the variation in its modulus of elasticity for soil with a thickness of e=0.5 m and a depth of deflection of Df=0 m. The results of the numerical models are superior to those obtained from the GSLCC method which suggest that as the modulus of elasticity increases, the load capacity increases. Additionally, for the first two modules which are considered fine soils, the behavior of the data obtained from the numerical modeling software is similar to that of the analytical results. This suggests that as the depth of the soil increases there is minimal variation in the data whereas in soils with higher elastic moduli or hard soils, the behavior of the data varies considerably as depth increases.

B. Stratified Soil (2 Strata)

The results of the analytical methods (APM, Terzaghi, and imaginary foundation) and numerical methods (Abaqus) for two strata with varying depths of displacement and thicknesses are shown below. The numerical models and analytical calculations were calculated for a Df=0 m with a thickness of e=0.15 m are shown in Table 8.

Table 8 Results of numerical modeling and analytical methods, Df=0 m, e=0.15 m.

| Soils | Abaqus [kPa] | APM [kPa] | Imaginary foundation [kPa] | Terzaghi Method [kPa] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 58 | 8328 | 43 | |

| 2 | 122 | 8812 | 91 | |

| 3 | 577 | 9730 | 568 | |

| 4 | 613 | 580 | 1279 | 1096 |

| 5 | 111 | 94 | 221 | 178 |

| 6 | 43 | 45 | 110 | 84 |

The graphic results of the stratified soil (2 strata) of soil combination 1 Df=0 m and e=0.5 m, are shown as a contour diagram of plastic deformations in Fig. 9 and of vertical forces in Fig. 10.

For the results of the numerical modeling and analytical calculations with a Df=0 m and e=0.5 m, the results are shown in Table 9.

Table 9 Results of numerical modeling and analytical methods, Df=0 m, e=0.5 m.

| Soils | Abaqus [kPa] | APM [kPa] | Imaginary foundation [kPa] | Terzaghi Method [kPa] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 40 | 5128 | 43 | |

| 2 | 81 | 6120 | 91 | |

| 3 | 565 | 8414 | 568 | |

| 4 | 573 | 612 | 4372 | 1592 |

| 5 | 52 | 102 | 805 | 279 |

| 6 | 31 | 49 | 413 | 130 |

The results of the analysis using a Df=0.5 m, for an e=0.15 m as shown in Tabla 10.

Tabla 10 Results of numerical modeling and analytical methods, Df=0.5 m, e=0.15 m.

| Soils | Abaqus [kPa] | APM [kPa] | Imaginary foundation [kPa] | Terzaghi Method [kPa] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 165 | 21821 | 168 | |

| 2 | 328 | 22789 | 323 | |

| 3 | 1464 | 24645 | 1696 | |

| 4 | 1463 | 1727 | 291 | 1719 |

| 5 | 326 | 332 | 52 | 327 |

| 6 | 149 | 173 | 26 | 169 |

The results of using a Df=0.5 m and e=0.5 m are shown in Table 11.

Table 11 Results of numerical modeling and analytical methods, Df=0.5 m, e=0.5 m.

| Soils | Abaqus [kPa] | APM [kPa] | Imaginary foundation [kPa] | Terzaghi Method [kPa] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 152 | 14805 | 168 | |

| 2 | 291 | 16975 | 323 | |

| 3 | 1537 | 21845 | 1696 | |

| 4 | 1383 | 1804 | 1697 | 2437 |

| 5 | 272 | 354 | 323 | 489 |

| 6 | 117 | 186 | 168 | 248 |

The analysis of two strata while taking into account the Drucker Prager criterion are shown in Table 8 to Table 11 and are composed of soils 1, 2, and 3.

The load capacity determined using the finite element method and Imaginary foundation are very similar while the results from the APM method are notably higher. This is due to the fact that this method in theory [20], says that better results are obtained when hard soil is on top of soft soil. This clarification is made again in the Terzaghi method which omits a combination of the first three soils since it has not been defined for these soil structures.

An analysis of hard soils on top of soft soils are represented by the combinations of the last three rows of Tables 9 to 12.

When comparing the results obtained from the Terzaghi and APM methods shown in Tabla 10, the APM method has a greater value than the reference value obtained in Abaqus. This is the contrary to the value obtained using the Imaginary foundation method which gives a lower value than that of Abaqus. A unique case is presented in soil combination 5 which demonstrates a difference in the results between the analytical method (Terzaghi's method) and the numerical method (Abaqus) which is less than 1.

The results of soils 4 and 5 and are about the Imaginary foundation and Terzaghi method are lower than those of Abaqus. This contrasts the results using the APM method in which the Abaqus results are higher as shown in Table 8. Furthermore, for soil 6 all of the results from the analytical methods are greater than the numerical methods.

The values obtained from the modeling in Abaqus are lower than the results using analytical methods as shown in Table 11; however, in Table 11 the values are closest to Abaqus. The values increased with the imaginary foundation method being closest, followed by the APM, and the Terzaghi method having the greatest difference. In the case of

Table 9, the values from the analytical methods closest to the numerical ones are those obtained using the APM method. This method resulted in a difference between 38 and 49 kPa, followed by the Terzaghi method with a difference between 227 and 1019 kPa, and finally the imaginary foundation method with results which are further from those found using Abaqus.

IV. CONCLUSIONS

After the numerical and analytical calculations had been performed, it was concluded that the variables that primarily influence the loading capacity in soils of one stratum and two strata are the friction angle, yield stress, and failure displacement (load - boundary condition). The most resistant soils do not fully plasticize (high yield stress values) because they do not achieve the levels of deformation necessary to cause failure. This suggests that it would be necessary to reach very high levels of deformation that cannot be represented with the conventional finite element method. When meshing is performed, finer materials provide better rendering levels, but result in more computational time to create the model in the program. Gravity must be considered in the finite element model in order for the model to have a natural geostatic behavior. The APM method and the numerical modeling method provide the best approximate for what would be physically and semi-empirically expected in a stratified soil structure (2 strata) with a hard soil on top of a soft soil for the evaluation of bearing capacity using elastoplastic behavior. On the other hand, the imaginary footing analytical method and the numerical modeling method are the best for determining what is to be physically expected semi-empirically when there is a soft soil on top of a hard soil. The results of the APM method for soft soils on top of hard soils do not represent results that agree with other methods and the respective values that would be physically expected in the field. As a result, it is not recommended to take these results into account as a design method in the latter case. Finally, this study highlights that the Prandtl fault is reproduced or formed in detail in numerical models when the modeled soil thickness is less than 1m.