Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Historia Crítica

versión impresa ISSN 0121-1617

hist.crit. no.51 Bogotá set./dic. 2013

Ranching and Market Access in the Backlands: Mato Grosso, Brazil, ca. 1900-1940s*

Robert W. Wilcox**

** Profesor asociado de Historia en el Departamento de Historia y Geografía de la Northern Kentucky University (Estados Unidos). Doctor en Historia de la New York University (Estados Unidos). Entre sus publicaciones recientes se destacan: "The Ethnocentric Steer: Perceptions and Obsessions in the Introduction of European Livestock Science into Brazilian Tropical Cattle Ranching, c.1880-1950", Albuquerque: Revista de Historia 1: 2 (2009): 9-43, y "Confronting Region and Environment in Mato Grosso: Variation and Ambiguity of Cattle Ranching, 1870-c. 1970", Debates e Tendencias 9: 1 (2009): 109-133. wilcox@nku.edu

La ganaderia y el acceso al mercado en una región lejana, Mato Grosso, Brasil, c 1900 a 1940

RESUMEN:

Por décadas historiadores economicos de América Latina han estudiado las materias primas, para explicar el carácter de las conexiones comerciales internacionales de la región, pero muy pocas han reflexionado sobre la ganadería. En este artículo se propone que esta falta de interés se encuentra relacionado con las características propias de las regiones ganaderas. Por ejemplo, examinando el estado brasileño de Mato Grosso, se observa que las dificultades para ingresar en el mercado están relacionadas directamente con la combinación de prioridades contradictórias, ineficiencias, e ideas preconcebidas. Se concluye que esta falta de dinamismo oculta las transformaciones que impactaron de manera significativa otras regiones ganaderas, que merecen más atención en un momento en el que los efectos de la ganadería tropical capta la atención pública.

PALABRAS CLAVES:

Mato Grosso, 1900-1940, ganadería, transportación, razas de ganado, zebu.

Ranching and Market Access in the Backlands: Mato Grosso, Brazil, ca. 1900-1940S

ABSTRACT:

For decades, economic historians of Latin America have studied the raw material to explain the nature of international commercial connections in the region. However, very few have focused on stockbreeding. The authors propose that this lack of interest is related to the characteristics of stockbreeding regions. For example, by examining the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso, one can observe that the difficulties to enter the market are directly related to a combination of contradictory priorities, inefficiencies, and preconceived ideas. The authors conclude that this lack of dynamism hides transformations that significantly impacted other stoc-kbreeding regions, which deserve more attention at a time when the effects of tropical stockbreeding are capturing the public's attention.

KEYWORDS:

Mato Grosso, 1900-1940, stockbreeding, transportation, cattle breeds, zebu.

A criação de gado e o acesso ao mercado em uma região longínqua: Mato Grosso, Brasil, c. 1900 a 1940

RESUMO:

Por décadas, historiadores económicos da América Latina vêm estudando as matérias-primas para explicar o caráter das conexões comerciais internacionais da região, mas poucos refletem sobre a criação de gado. Uma hipótese para essa falta de interesse se encontra relacionada com as características próprias das regiões pecuaristas. Por exemplo, ao examinar o estado brasileiro do Mato Grosso, observa-se que as dificuldades para entrar no mercado estão relacionadas diretamente com a combinação de prioridades contraditórias, ineficiências e ideias preconcebidas. Conclui-se que essa falta de dinamismo oculta as transformações que impactaram de maneira significativa outras regiões pecuaristas, que merecem mais atenção em um momento no qual os efeitos da pecuária tropical capta a atenção pública.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE:

Mato Grosso, 1900-1940, criação de gado, transportação, raças de gado, zebu.

Artículo recibido: 28 de noviembre de 2012 Aprobado: 22 de abril de 2013 Modificado: 6 de junio de 2013

DOI: dx.doi.org/10.7440/histcrit51.2013.04

Introduction

Much of the economic history of Latin America has revolved around the role of commodities in the region's development. For example, a recent volume edited by Steven Topik and others investigates several export goods across Latin America utilizing the concept of "commodity chains." For the editors, this approach is valuable because it goes beyond simple production to "[...] clarify how the development of export commodities [...] was driven by a complex set of social and economic factors that were both local and international."1 They also emphasize that "[... ] there is not one world market; there are myriad and often segmented markets, and indeed, the same commodity may have numerous chains depending on its end use or destination."2

The Topik volume contributes a valuable perspective for understanding Latin American commodities over the past five hundred years, most particularly the complex character of the export trade, but it does not address livestock and meat, particularly beef, a lacuna readily admitted by the editors.3 In fact, with some exceptions, cattle and beef have not attracted the same scrutiny as other commodities, and yet exhibit similar characteristics. There are various reasons for this oversight, but my sense is that to some extent it may have to do with ranching itself, particularly its remote character and often delayed ability to access developed, globally-centered markets. Scholars, therefore, have tended to bypass such regions as more conspicuous sectors attracted their attention. There is a danger in this of missing inputs that have had significant influence in the development of future dynamic cattle economies. This is the case of one "segmented" ranching market in the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso, which was slow to appear on the national and international stage, but whose history reveals not just obstacles to development but also specific measures taken to overcome barriers that ultimately established a precedent for tropical ranching, most noticeable today in the Amazon Basin.

1. The Mato Grosso Cattle Economy and Conflicting Priorities

In recent decades the cattle economies of the Brazilian states of Mato Grosso do Sul and Mato Grosso have become important players in the nation's economy, together hosting over 50 million head, the largest cattle herds in the country, while significantly contributing to Brazil's dynamic beef export trade,4 although this was not always the case. Despite having been a cattle region since the mid-nineteenth century, until the 1950s-1960s Mato Grosso was considered distant and backward, and exports were limited.5 Typically, this lack of development was blamed on ranchers and their alleged apathy in expanding production, but there were in fact a series of complex factors that limited market integration and delayed the insertion of Mato Grosso into the export trade, most of which were beyond the control of ranchers.

Cattle raising was a part of the Brazilian economy from colonial times, but most production was concentrated in the southern state of Rio Grande do Sul or in the Northeast. Central Brazil contributed to national consumption, but this was relatively minimal and did not include export.6 As in neighboring regions, ranching in Mato Grosso was open-range, a form that bordered on "subsistence," since in many cases this meant uncertain land tenure and uncontrolled, indeterminate numbers of cattle of unreliable quality. Success depended on several interrelated factors, but the obstacles were considerable, most especially the contradictions and inertia of national and state governments, inefficient transportation structures, limitations of geography, and preconceptions about animal husbandry. Until the 1940s, these pieces only rarely coalesced to produce appreciable development, although the sector exhibited characteristics of adaptation that would have profound impact on future ranching regions in Brazil.

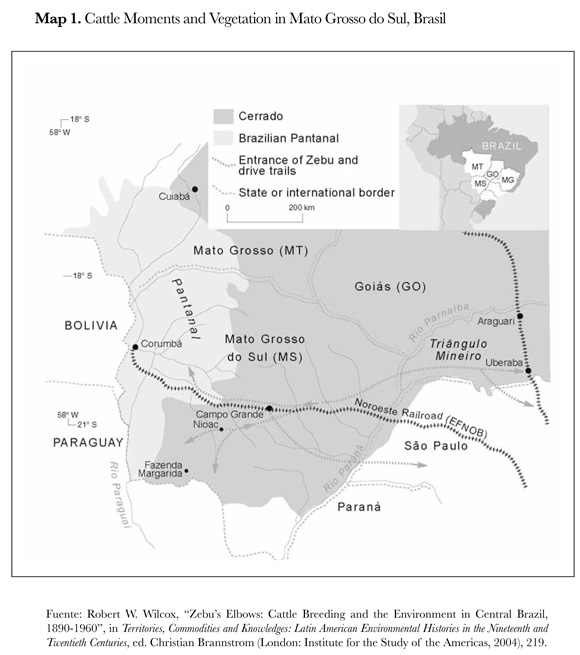

Before 1900 Mato Grosso experienced modest growth and gradual interest from the outside. By far the least populated region of the country, the state's population doubled between 1890 and 1910, from 92,800 to an estimated 185,800 persons by 1910. Official state income doubled from US$125,000 to over $272,000, although expenses almost always exceeded income, leaving little leeway for government planning. The role of ranching was small, but attracted by broad expanses of grass in both the annually-flooded Pantanal and the semi-arid savanna [cerrado], ranching settlement expanded. The cattle population flourished, growing from an estimated 800,000 in 1887 to 2.5 million in 1912, the fourth largest herd in the nation.7

While there was some activity in jerky [charque] and beef-bouillon production ever since the 1880s, World War I generated an urgent demand for meat that benefitted the entire Brazilian cattle sector, including Mato Grosso. National frozen- and chilled-beef exports increased dramatically, from a negligible 1.5 tonnes in 1914 to over 65,000 tonnes by 1917. In the same period, exports of canned meats climbed from fewer than 230 tonnes in 1913 to 6,500 tonnes, and jerky exports from 20 tonnes to 8,700 tonnes. The war was responsible for the creation of the Brazilian frozen-beef industry, centered in São Paulo, which had previously not been able to compete with Argentine and Uruguayan domination of the world market, causing Brazilian processors to rely on jerky production. While there was an abrupt slowdown of frozen-beef production immediately after the war, by 1919 the industry was firmly established and would become a significant economic sector over the following decades.8

A marginal supplier of beef to the São Paulo market before the war, southern Mato Grosso was soon drawn into the wartime national economy, exporting increasing amounts of live cattle to the beef slaughterhouses [frigoríficos], while pastures, cattle slaughter and much-needed infrastructure began to receive attention. The state saw significant opportunities for its cattle products, specifically live animals to feed thefrigoríficos and new jerky factories [charqueadas] in Mato Grosso itself.Jerky was sent to markets in the Brazilian Northeast and Cuba. By 1915, the Osasco slaughterhouse in São Paulo alone processed over 36,000 animals from Mato Grosso, most of which went to the export market. If the totals of slaughter for hides and jerky are included, in 1919 Mato Grosso contributed 265,000 head of cattle, which represented roughly 10 percent of the state herd.9

The immediate post-war period was one of crisis for Brazilian ranchers, particularly in Mato Grosso. Prices plummeted across the country, prompting ranchers to sell their cows in order to pay off debts contracted during the wartime boom. Desperate pleas were made for tax and transportation relief from the government. By this time the state government was well aware of the importance of the cattle sector to Mato Grosso's economy, yet it was slow to address the many fiscal obstacles to production. Some taxes were reduced or revoked, and fines on late payment cancelled, but when a commission of federal deputies from cattle-producing states sought solutions to the national cattle-ranching crisis, they came up against a series of federal impediments as reported by the Mato Grosso president: a) a high salt-import tax, since the jerky industry nationwide used imported rather than Brazilian salt; b) excessive freight charges for both salt and beef, which included a federal transportation tax; and c) São Paulo state taxes on frigorífico production and fattening pastures.10

Although response was slow, in mid-1924 the inflated cost of meat in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo prodded the federal government into declaring tax and internal tariff relief on certain meat products, particularly jerked and dried beef, and encouraging salt production in Brazil. The measures had a temporary salutary effect on the cattle industry and on the cost of living for poor urban residents, who were the main consumers.11 Nonetheless, such relief was inadequate to stimulate the Mato Grosso cattle industry since there were several other obstacles that state and federal authorities consistently failed to address adequately, above all, transportation.

2. Transportation: Shipping by Boat and Rail

Until the First World War, Mato Grosso depended upon shipping on the Paraguay River and unreliable cattle trails to connect with the outside world. Corumbá was the state's economic and cultural link to the wider world, and all cattle products from the Pantanal were shipped through that town and down the Paraguay River to Montevideo, where they were trans-shipped to other destinations, primarily in Brazil. Goods were carried by Lloyd Brasileiro, founded in 1890, but the company endured financial problems almost from its inception, and passed back and forth from public to private hands until it was eventually taken over by the government in 1913. These problems harmed local economies that relied on the service and were often considered of only secondary importance by the directors in Rio de Janeiro. Government financial support was sporadic, sailings irregular and often delayed, freight charges onerous, and goods often damaged or stolen.12

Argentine or Paraguayan companies were alternatives, but since their priorities were not in Mato Grosso, they charged prohibitive freight rates to Carumbá. In 1912 it cost US$4.10 to transport a tonne of freight from Montevideo to Europe or North America, a journey lasting three weeks to a month, while the rate for the two-week upriver trip from Montevideo to Corumbá was nearly double that amount. In 1907, charges for the export of a tonne of beef jerky from Miranda to Rio de Janeiro was over US$40. Freight rates for imported items were generally cheaper than for exports, and while they changed little over the years, they did eventually increase in 1928 when the Argentine giant Mihanovich charged an exorbitant $38.60 per tonne or 1.2 cubic meters [40 cubic feet] between Buenos Aires and Corumbá.13

Despite these obstacles, between 1906 and 1912 the number of ships entering Corumbá increased from 48 to 128 and vessel tonnage grew accordingly. Export records show that the increased volume of freight consisted almost exclusively of cattle products, particularly beef jerky. Exports of jerky from Corumbá jumped from 52,000 kilos in 1905 to 1.6 million kilos by 1912, while between 1919 and 1925, stimulated by the demand of World War i, exports from charqueadas along the lower Paraguay River doubled from 800,000 to 1.5 million kilos.14

The fundamental problem of shipping was not resolved by this apparent success. Lloyd had significant management issues that led to suspension of service between Montevideo and Corumbá in 1914. It then proceeded to rent out its boats to a local import-export firm with priorities in Argentina and Paraguay, but not in Mato Grosso. As a result, Mato Grosso ports "waited months with no news of national ships." In March 1923, there were over 800 tonnes of beef jerky warehoused in Corumbá awaiting shipment to Montevideo.15

Lloyd returned to the region in the early 1920s, but it took time for conditions to improve. A newspaper article in 1924 observed that while Mihanovich covered the round-trip Montevideo-Corumbá run in 25 days, it took Lloyd up to three months to do so. In addition, the Lloyd boats could only carry 750 to 800 tonnes of cargo per voyage while those of Mihanovich had a capacity of 5,500 to 8,000 tonnes. By 1930 it appears that service provided by the Brazilian carrier had improved since three new ships had been added and total annual shipping in tonnage entering Corumbá from foreign ports almost tripled between 1928 and 1931. Furthermore, the state established regular service between Porto Esperança on the Paraguay River and Corumbá to link up with the recently-built railroad, and Corumbá briefly recovered its position as a commercial entrepôt for Mato Grosso.16 Nevertheless, the price inequities and endemic service delays of fluvial transport indicate Mato Grosso's geographic vulnerability in connecting to commodity markets, and explain why the state looked forward to the arrival of the railway as the solution to its isolation. Shipping by river had proved inadequate to satisfy the region's needs and between 1930 and the 1950s the service gradually declined. The railroad, however, which had promised a long-awaited solution to the shipping problem, also fell short of satisfying Mato Grosso's needs.

As river transport proved both uncertain and inadequate, the state government expressed a need for easier and more cost-efficient transportation routes for markets to the east. Cattle trails that had been in use since the 1850s were long and the trip was arduous; there was little water en route, and animals arrived at their markets in Minas and São Paulo so thin that they required several months of fattening before slaughter. In addition to this, there was the Paraná River, which was a major obstacle to expanding cattle transport out of the state until a bridge or at least barges were available to facilitate a crossing. Private entrepreneurs did invest in such infrastructure, but trails were expensive and unreliable since the state refused to award tax concessions or introduce other measures to facilitate operations, so they eventually resorted to betting on the success of a railroad link to São Paulo. The railroad was finally completed in 1914, but the conditions surrounding its operation precluded the export of cattle by rail, thus forcing ranchers to rely on trails well into the 1940s.17

The concept of a railway across Mato Grosso had been envisioned ever since the mid-nineteenth century. Pressure to establish links between the Brazilian coast and Cuiabá began to mount after the end of the Paraguayan War [1864-1870], in the wake of Rio's temporary "rediscovery" of its interior province. Despite numerous projects proposed and concessions awarded, nothing concrete was undertaken until 1903. Geopolitical rather than economic concerns convinced the federal government that a railroad linking its remote territories to the coast was essential. A line was proposed from São Paulo to Cuiabá in 1905, but promises made to Bolivia after that nation's loss of Acre to Brazil, and the strategic concept of a transcontinental railway linking the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, caused it to be redirected to Corumbá in 1907. Fernando de Azevedo later described it as Brazil's "first political highway."18

The railway was completed in 1914 and, after some dispute between the federal government and the original concessionaries, Rio took over the full operation in 1917. The entire route became known as the Estrada de Ferro Noroeste do Brasil (EFNOB), more commonly referred to as the "Noroeste," and extended over a total of 1,273 kilometers, 837 of them across Mato Grosso.19

Expectations were high among Matogrossenses as the railroad neared completion. Cattle ranchers envisioned raising and fattening animals at home for direct export to the São Paulo slaughterhouses; a journey of 36 hours by rail would replace one of three months on the trail. Ranchers also hoped to gain more influence over a market that still remained in the hands of the cattle buyers and the slaughterhouses with their winter pastures. In addition, greater access to the region would reduce import costs and attract settlers. Both human and financial capital were seen as natural extensions of efficient transportation and were expected to contribute to freeing the state from trade controlled by a small number of economic agents in São Paulo and the Río de la Plata. It was hoped that Mato Grosso could now determine its own destiny.20

While the inauguration of service in Mato Grosso in 1914 was timely, the railway to the Paraguay River at Porto Esperança was not completed until 1917 due to the difficulties of building across part of the Pantanal. Regular service was unsafe, especially during the rainy season, and there were two other major physical obstacles to securing regular service between São Paulo and Corumbá, i.e. the Paraná and Paraguay Rivers. Until a bridge was completed linking Mato Grosso with São Paulo in 1928, rail cars had to be rafted across the Paraná, while service from Porto Esperança to Corumbá was continued by small river- steamboats until another bridge was finally completed across the Paraguay River in 1947 and service extended to Corumbá in 1953. The railroad had been a source of considerable frustration among Mato Grosso residents until then.21

Although the positive impact of the railroad was slower in coming than expected, by 1920 it had opened up the state to development possibilities that had been unimaginable before. The influx of people, many of them land speculators and adventurers, but some settlers as well, first transformed the areas along the railway line and eventually all of southern Mato Grosso. Dusty, torpid villages expanded overnight, towns were created out of the wilderness, and modern facilities and ideas flowed into the state. From only 5,000 inhabitants in 1912, the municipality of Campo Grande catapulted to over 21,000 by 1920, while the town itself increased from 1,200 to 6,000 inhabitants. By 1940, the municipality had a total of 50,000 inhabitants, at least half of them residing in the town. Over all of southern Mato Grosso the population almost doubled from 74,000 in 1912 to 130,000 in 1920, and by 1940 this figure had increased to 239,000. Along with population growth came regular postal service and telegraph communications, luxuries that Campo Grande and other towns had only dreamed of before.22

Economic activity expanded proportionately. Exports of live cattle and cattle products increased and, although there was a slowdown immediately after the war, by the mid-1920s the south unquestionably drove the state economy. Part of this dynamism was the result of foreign investment that had been attracted to the region with the completion of the railway. American entrepreneur Percival Farquhar's Brazil Land, Cattle and Products Company created a series of integrated ranches in Mato Grosso, Paraná and São Paulo even before the line was fully operational, and other foreign investors entered during and after the wartime boom, founding ranches and charqueadas near the rail line. These companies helped to raise land values and stimulate greater interest in ranching. The railroad permitted an inflow of items such as salt, wire, grass seeds, breeder bulls and machinery, and it also facilitated travel for cattle buyers, thus transforming the marketing of cattle, at least as far as access to ranches was concerned. The number of charqueadas that sprang up in the towns along the railroad was impressive - a total of twelve out of the twenty-five that existed in 1925 were located on or near the rail line, an impressive increase, since there had been only one in 1914.23

Nevertheless, the expectations raised by the arrival of the railroad were overly ambitious. Mato Grosso, although connected to the São Paulo meat-processing industry, was not a priority in the global plans of the Brazilian government, nor was the operation of the federally-owned Noroeste. Even during the export boom of the First World War, the volume of cattle and cattle products shipped out of the state by rail did not meet expectations. As early as 1916 the state president had complained about service on the railroad. He was especially concerned about freight rates, arguing that unless they were reduced, Mato Grosso production would have no future. He pointed out that the rates were triple those charged for transporting similar products over the same distance in Rio Grande do Sul. While cargo volume was much greater in Rio Grande do Sul than in Mato Grosso, such rate differentials were nonetheless excessive. This inhibited the expansion of hide production in Mato Grosso and forced producers who were already in business to rely on river transport, the very dependency they had hoped to escape.24

The freight-rate issue became a constant problem over subsequent years. Beef jerky production increased considerably in the years after World War i as cattle prices dropped and the stock of animals grew. Additionally, although several plants were set up along the railroad, they tended to produce tiny quantities compared to their fluvial rivals, and in some cases were forced to export their products via the Paraguay River anyway. The rates charged by the efnob were as high as $70 a tonne during the 1920s, 80 percent higher than those of the exorbitantly expensive Mihanovich fluvial service. None of this changed, despite frequent calls for cheaper freight rates and lower taxes, until 1928 when the federal government, in response to product-switching at the port of Montevideo, levied an import tax on any Brazilian jerky destined for the Brazilian market that was trans-shipped through other nations.25

Consequently, the Mato Grosso industry could not afford transshipment at Montevideo and producers therefore requested that rail freight rates be reduced by 50 percent and that the government establish a direct port-to-port fluvial service. In response, the Ministry of Transport, which was in charge of the efnob, agreed to reduce rates for charqueadas that filled the rail cars with at least 20 tonnes of jerky, but it only guaranteed transport to Bauru in central São Paulo, with re-dispatch to market from there. This revealed the other major stumbling block in Noroeste service - rolling stock. One respondent pointed out that, aside from there being a chronic shortage of rail cars to begin with, the cars provided were inadequate to satisfy the ministry's 20-tonne minimum cargo requirement since their maximum capacity was only 16 to 18 tonnes. In addition, transferring freight in Bauru would have threatened cargos since the railroad lacked sufficient warehousing space. Any delay in transport [and they were more than likely to occur, considering the efnob's concentration on the transport of coffee in the state of São Paulo) would have left the jerky exposed to the elements, thereby increasing the risk of spoilage. Indirect dispatch would also have dried up credit, since banks were unwilling to finance goods in transit. Intensive lobbying by Mato Grosso federal deputies in Rio eventually won the government over and a 50 percent reduction was awarded on any full cars and shipment was to be dispatched directly to the destination point. This decision probably saved the industry in Mato Grosso, as export figures reveal steady activity from 1929 into the mid-1930s.26

Ranchers were faced with problems similar to those of the charqueadas in the export of live cattle. While rates for cattle drives and those charged by the railroad were comparable [between $4.50 and $5 per head) by the mid-1930s, the problem lay largely in the company's inadequate provision of rolling stock. When available, most cars could accommodate at most 18 to 20 head of live cattle, which was not cost-effective for the railroad. Furthermore, service was infuriatingly slow. In 1924, the journey from Campo Grande to Rio took a total of 52 hours, given ideal connections and barring delays, which were in fact quite common. The trip took 26 hours longer between Corumbá and Campo Grande, including 12 hours by boat between Corumbá and the rail head at Porto Esperança. To make matters worse, there were no facilities along the route for feeding cattle or even for providing them with water. Thus, cattle transported from Campo Grande to the São Paulo stockyards were forced to endure a minimum of 40 hours without food or water. Yet these were under ideal conditions since most cattle were forced to suffer up to 7 or 8 days in the cattle cars, receiving little if any attention. It takes no imagination to visualize the deplorable state of the animals at the end of their journey. In purely economic terms, this required a period of recuperation which, considering the costs, was simply prohibitive for rancher and frigorífico alike.27

But the main problem was that there were simply not enough cars for transporting live cattle. From the viewpoint of Noroeste management, it was basic financial logic to favor the São Paulo sector over that of Mato Grosso. By transporting coffee, the railroad operated at a profit in São Paulo, while it ran a constant deficit in its Mato Grosso sector, where only low-value cattle products were available for transport. While most Matogrossenses complained about freight rates, the company in turn lamented that if it were to make its operation profitable in the state, it would have to raise rates so high that no one would be able to pay for them. The railroad certainly had some serious budgetary problems throughout its existence, aggravated between 1930 and the mid-1940s when the proportion of coffee cargos declined as the export market shrank during the worldwide depression, and exhausted coffee lands in São Paulo were converted to ranching. Meanwhile, the problem of insufficient cars continued, as seen. In May 1934, when ranchers in certain areas of Mato Grosso complained they had been waiting over a month for transportation. Many had turned to the drives since they were operating on short-term credit and could not afford delay. Some improvements were reported near the end of the year, but there were too few and they were not continued. By the 1940s, rail service once again had deteriorated in Mato Grosso, although the Getúlio Vargas dictatorship [1930-1945) belatedly began to invest in transportation and settlement in the region during World War n.28

In the end, the railroad failed to bring the rapid development eagerly anticipated by Matogrossenses. Even when the government took over operations, it did little to stimulate exports, serving more to introduce people and goods into the state than the opposite. Producers were forced to be innovative in seeking solutions, but inadequate or non-existent transportation meant that "improvements" were delayed in the Mato Grosso cattle industry. Once again, the limited opportunity offered by rail transport illustrates the segmented character of Mato Grosso ranching. This went beyond river and rail, as outside assessments of the inadequacy of ranching to meet the challenges of a modern market focused on the form of ranching, the lack of "rational" husbandry, and the inadequacy of the cattle breeds raised in the state.

3. "Rational" Ranching, Improvements, and Cattle Breeding

Over much of the period under study, ranching in the region received a good deal of criticism for its underdevelopment. In 1907, Virgílio Alves Corrêa listed the reasons why ranching could not progress in the state. In addition to high import taxes and freight rates and poor transportation service, he outlined the "ease" with which ranching could be undertaken, and criticized the government's failure to recognize the importance of the industry to the region and to its own income, despite its reliance on taxes from cattle production. But he did not spare the form of ranching from his criticism, and especially condemned the practice of communal cattle raising and the burning of fields, which exhausted pastures and added to care costs and losses of animals due to lack of oversight. Corrêa urged the federal government to support local ranching through subsidies, tax exemptions and free technical training.29

The concern was primarily one of open-range ranching. Until land took on a value as something other than a medium for animals to go forth into and multiply upon, cattle raising relied on nature for its survival. There was a certain logic in this, for if climate is sufficiently benign, as it was in most of Mato Grosso, cattle could survive on their own with few if any inputs from ranchers. There was little competition from wild herbivores, predators were a nuisance but not a major threat, and there was plenty of forage and even natural salt in some regions to sustain significant numbers of animals.

Naturally, the quality of cattle for meat production was often inferior compared to that of more developed livestock economies like Argentina or Rio Grande do Sul, for the flesh of a semi-feral animal is inevitably lean and tough, and the quantity and quality of meat and hides produced by such cattle generated only limited income. This was a business of subsistence ranching, despite the vast expanses of territory claimed by some ranchers, and unless the expensive inputs necessary for improvements were compensated for by higher cattle prices, little attempt could be expected to be made to improve the situation. Here, the isolation of Mato Grosso was decisive, for the cost of raising an animal any other way could not be recovered in its sale. Poor transportation, scarce rural credit, high taxes and competition from other ranching areas of Brazil combined to prevent Mato Grosso ranchers from modernizing their operations, even if they possessed the will and knowledge necessary for a modest beginning. Under these circumstances, open-range ranching was not due to a simple "backward" view of the world, but rather the only available response to environmental and economic conditions that limited the ranchers' scope of action.30

As noted, official action to rectify these conditions was seldom forthcoming, although solutions were consistently proposed. World War i was the greatest stimulus, even though the process had begun a few years before the war. In 1912, President Costa Marques suggested control of the sale of breeder-age cows and heifers, subdivision of large ranches, introduction of fencing on a wider scale, improvement of transportation facilities, and development of an effective medicine to combat peste de cadeiras [surra) in horses, a disease that was common in the Pantanal. He suggested that the state offer assistance in finding a cure and authorized establishing an experimental ranch to improve cattle breeds. These suggestions, though not particularly new, now fell on more responsive ears thanks to the wartime demand for cattle products, and some measures were eventually taken to support the sector.31

World War i motivated the state to support the creation of a live cattle market [feira de gado) in 1919 at Três Lagoas on the Paraná River. This measure was intended to encourage the application of modern ranching methods as practiced in Argentina and the United States, and to aid in the marketing of Mato Grosso cattle to the São Paulo slaughterhouses. As it turned out, however, the operation was both insufficient and poorly maintained.32

The experience of the Feira de Gado reflects the government's contradictions with respect to promoting cattle production. The feira had operated since 1920 under private concession, but by 1925 it had contributed little to stimulate either local business or the Mato Grosso cattle industry in general. Letters written to the Três Lagoas weekly A Noticia in mid-1925 explained that the best efforts of the directors had achieved nothing because the state government offered the feira little support. Bridges along the cattle trails linking the cattle center of Campo Grande with Três Lagoas had still not been built, the feira offered neither pesticide baths nor developed pastures, there was no zootechnical station, and there was not enough water or electricity. They also mentioned that the demand for cattle was greater than supply at the time, hence animals were purchased in the traditional way, on the ranches themselves, bypassing the feira altogether and undermining the promise of competition and higher prices that the feira represented. The president's address of the following year bowed to the critics and admitted that as long as bridges between Três Lagoas and Campo Grande were not completed, and due to the traditional type of cattle raising practiced in the state, the feira was simply irrelevant. He might also have added high taxes charged by the feira, while a serious obstacle to greater expansion, accessible credit, required the intervention of the state in the marketplace, a measure that was extremely slow in coming.33

There was some hope, however, as reported in another Três Lagoas newspaper. At the start of 1927, a veterinary post was opened to ranchers. It was under the direction of the federal Ministry of Agriculture and offered information, vaccines and other medicines. This was apparently part of a rudimentary program undertaken by the federal government, one for which rancher organizations and the state government had lobbied for years. It appears to have stood alone until an agricultural station for the study of pastures and local conditions was set up in the Pantanal after World War ii. However, in 1918 the federal government also proposed to set up a fazenda modelo [model ranch) in Campo Grande, on land provided by the state. In his 1925 report, state President Mario Corrêa da Costa that the model ranch at Campo Grande was not yet functioning, even though the state had bought the land and donated it to the Ministry of Agriculture, and a director had been appointed in 1924. The ranch was still idle in 1929.34

With the Getúlio Vargas dictatorship, however, Rio paid more attention to establishing Brazil's hold on its remote regions than had previous governments and by 1936 the ranch was in operation, introducing exotic grasses and engaging in breeding experiments under the direction of the Ministry of Agriculture. Although extremely limited in its scope until the cattle economy began to expand in the 1960s, the site became part of the national center for the study of beef cattle in 1977, under the auspices of the federal Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária (EMBRAPA).35

The original breeds of cattle in Mato Grosso were muscular, heavy-boned animals with short legs, long curved horns, and powerful front quarters, similar to the famous Longhorn cattle that roamed the North American range. Over time, a series of regional breeds with specific adaptations developed as products of natural selection. The most noticeable development was the enlargement of horns, a necessary feature in an open-range ranching system for defense against predators, as well as wider hooves, thicker hides and stronger constitutions. Observers noted the slow maturation, light weight, and allegedly weak hindquarters as the principal results of the so-called "degeneration" of Zebu, while their meat was also considered tough and sinewy. Furthermore, the cattle had become semi-feral: they shied away from humans and readily put up a fight at roundup time, thereby displaying a temperament that was hardly ideal for raising cattle on a commercial scale.36

Such obstacles indicate the relative underdevelopment of the local ranching industry in producing cattle to supply a broader market outside of the state. There were regular calls for improvement of breeds over the decades, particularly in terms of importing European stock, again taking the phenomenal success of Argentina and Rio Grande do Sul as models worthy of emulation. Government officials, ranchers, veterinarians, even presidents of the state, all suggested the introduction of Northern European breeds to improve local stock. There was a clear belief that the Mato Grosso ranching industry required larger, more productive animals if it was to provide greater wealth for ranchers and the state, but there was less understanding of the character of tropical ranching and the suitability of breeds to the region.37

The first major effort to import purebred European animals into Mato Grosso was undertaken by Brazil Land, which introduced a thousand purebred Durham and Shorthorn cattle from Texas just before World War i. This experiment was copied by a few ranchers in the region, particularly other foreign interests, but soon proved to be an abysmal failure. The breeds were hardly acclimatized to the Mato Grosso environment, unaccustomed as they were to the local forage, and they suffered from the intense sun and humidity, insect plagues as well as from the unfamiliar forage, finally succumbing to unusually harsh winters in 1917 and 1918. Considering their relatively delicate constitution, the animals may not have received the care they required, but the experience convinced Brazil Land of the need to raise more rustic breeds, and other ranchers of the inadvisability of importing any more European animals. The railroad's inability to provide regular transport for livestock also contributed to this decision. The solution chosen by Brazil Land, and already begun by a number of ranchers in the state, was to introduce Zebu (Bos indicus) and Zebu crosses. This exotic Indian breed was given the stimulus needed to consolidate its penetration of Mato Grosso, creating a cattle ranching revolution in the process.38

4. The Zebu Revolution

Between 1893 and 1914 over 2,000 breeder Zebu were imported into Brazil from India, one-half of them destined directly for the Triângulo Mineiro of western Minas Gerais state bordering on Mato Grosso. The Triângulo soon became the focus of Zebu raising in Brazil, and not even World War i discouraged importers. Between 1914 and 1921, when extensive imports ended, over 3,300 Zebu had been brought into the country.39

Considering the proximity of Mato Grosso to the Triângulo, it is no surprise that Zebu soon made their way into that state. Occasional introduction of the breed into Mato Grosso began soon after 1895. Several ranchers, particularly in the Campo Grande area, bought Zebu in Minas for resale in Mato Grosso or for their own ranches. Paulo Coelho Machado reported that his grandfather, Antônio Rodrigues Coelho, drove a herd of local cattle to Uberaba for sale in 1906, but due to a national economic recession could not sell the animals and was forced to trade his herd for 400 Zebu. He brought them back to his ranch near Nioac, keeping one-half for himself and selling the rest. Coelho later declared that this was the best investment he had ever made, since the quality of his stock improved significantly when the Zebu were crossed with "degenerated" local cattle. They were also admired for their adaptability to harsh environmental conditions like the regular flooding of the Pantanal or the periodic droughts of the cerrado, as well as their endurance on the long drives to fattening pastures in São Paulo.40

Nevertheless, ranchers in Mato Grosso did not always acquire Zebu as a matter of choice. Until the boom brought about by the First World War, the most important route for the export of Mato Grosso cattle was through Minas, also the major source for breeder animals. As a result, drovers from Minas often arrived in Mato Grosso for the annual cattle-drives trailing small herds of breeder Zebu as partial or full payment. In many cases, ranchers in Mato Grosso had little option but to accept Zebu blood into their herds since other breeds were almost impossible to find, or at the very least prohibitively expensive. Nonetheless, breeder Zebu were not exactly cheap. Around the turn of the century a purebred bull in Mato Grosso could fetch as much as US$1,000 to $1,200, while a cross brought $400 to $600. These were exorbitant prices for the day, but as more animals became available, prices declined.41

Still, few Mato Grosso ranchers could afford purebred cattle, or even the periodic purchase of crossed animals. The result was a gradual decline in animal precocity, average weight, and resistance to the open-range ranching conditions under which they lived. As early as 1907 Lisboa noticed that after four or five generations the Zebu's initial hardiness had disappeared, and the cattle had degenerated in all respects, especially in terms of body weight. They were still considered ideal as traction animals and for their ability to tolerate the long drives, but they were no longer producing as they had done in the past.42

Selective breeding and care were the crux of the matter. In itself, the Zebu was not prone to inevitable "degeneracy" as many of its detractors claimed, but inadequate attention did lead to a decline in quality over several generations. Fernand Ruffier and others have argued that the best way to improve cattle quality in Brazil (as always, compared to the phenomenal success of Argentina) was to create conditions under which the animals could prosper, including better pastures, closer attention by ranchers, and the establishment of zoo-technical education facilities. Allegedly, this was not understood by Brazilian ranchers, who believed that by simply injecting some Zebu blood into their herds, they could produce some miraculous breed that would require no further care. While this attitude did in fact exist, the ranchers' reluctance to practice such crossbreeding, particularly in regions like Mato Grosso, was more a matter of the expense involved. The financial reward for such care was either limited or non-existent and, therefore, the richest ranchers could afford the investment.43

Another issue was the quality of Zebu meat. Zebu detractors argued that the breed had less fat than European cattle and was thus unpalatable to the European consumer, compared to beef exported by Argentina. This argument was used by the London Board of Trade in 1918 when it banned the import of beef from Brazil. It is true that Zebu carry their flesh quite difíerently from other varieties of beef cattle, since animals of European origin usually have a thicker layer of subcutaneous fat to protect them against the cold, while Zebu generally show less marbling. This makes Zebu meat not only leaner, but also drier and potentially tougher when cooked. In today's world of health consciousness this might be considered a benefit, but it was a definite disadvantage at that time, particularly since Brazilian beef was in competition with the prized beef produced in Argentina. Fresh beef was seldom consumed in Brazil, except by the wealthiest, and even that group preferred lean cuts, so Zebu meat found a ready market among them. Nevertheless, since the future of the industry depended on exports, especially to Britain, the ban imposed by London caused consternation.44

The resulting furor saw some extremists calling for an end to the import of Zebu breeder- stock and the slaughter of all Zebu, so as to concentrate exclusively on the raising of European, and above all, English breeds. Ruffier responded by making a few salient points. He explained that the English had rejected Brazilian meat based on its poor quality which, despite the rhetoric of the London decree, had nothing to do with its Zebu origin. The Frenchman blamed poor preparation by the frigoríficos. Affected by the feverish demand for meat brought about by the war, scrawny animals were often slaughtered immediately upon their arrival from grueling three-month drives, followed by an excessively rapid freezing process that damaged the meat. As a result, the meat sent to England suffered from freezer burn, and was therefore tough and discolored. He concluded that such a poor product was the consequence of slaughterhouse haste, and pointed out that, along with the ban the Board of Trade had also openly recommended that Brazil import purebred English bulls to rejuvenate its herds. For Ruffier, this was an obvious British attempt to promote the interests of British breeders. It would not be the first time that London had used a seemingly minor issue to manipulate the market in for its own benefit.45

Despite such attacks, Zebu came to dominate as the major breed in central Brazil, largely due to its ability to thrive in varied tropical conditions and because it could easily withstand long and arduous cattle drives. In fact, for some observers Zebu revolutionized tropical ranching as they became the main breed in Mato Grosso by the 1930s. By 1940 the state reportedly had a higher proportion of Zebu in its herd than any other region of Brazil. Most of the Zebu were not purebred, however, since they were products of both deliberate and uncontrolled crosses with local animals. This only began to change in the 1950s when purebred animals were introduced, thus creating the conditions for Mato Grosso to become one of the country's major cattle-raising regions in later decades. Indeed, for many the eventual success of Zebu in Mato Grosso revolutionized tropical ranching across both the country and the continent, since Zebu are now the predominant breed in Brazil. This helped to open up the sector to initiatives that eventually overcame many of the obstacles outlined in this essay, including more dedicated government programs, the introduction of exotic grasses, and the development of more efficient transportation structures, and provided lessons that would be applied well beyond Mato Grosso itself.46

Conclusion

Ultimately, the conditions for successful cattle raising in Mato Grosso were promising but limited by a combination of remoteness from the rest of the country and its consumer markets, demanding geographical environments, limited fiscal attention to the region, weak transportation structures, and preconceptions regarding the quality of animal husbandry in the minds of observers and experts alike. Commodity chains in a region like Mato Grosso suffered from many broken links and rusty connections, obstacles that led to the slow and uneven development of ranching up until the late twentieth century. The dynamism seen in other economic sectors of Brazil over the same time period overshadowed the experience of Mato Grosso ranching and led to a general lack of appreciation of its significance. As impediments were overcome, beginning in the late twentieth century, what has been overlooked is the fact that the earlier struggles of the state's cattle sector provided valuable lessons that were eventually instrumental in expanding economic opportunities, not only in Mato Grosso but in other regions as well, most particularly the Amazon, and with decidedly mixed results. Given today's controversies surrounding the widespread social and environmental impacts of tropical ranching, this experience of Mato Grosso deserves greater attention.

Comentarios

* This article is part of ongoing research into the economic and environmental role of cattle ranching in the history of central Brazil, specifically Mato Grosso. My thanks to the Department of History and Geography at Northern Kentucky University for financial and other support.

1 Steven Topik et al., eds., From Silver to Cocaine: Latin American Commodity Chains and the Building of the World Economy, 1500-2000 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006), 360.

2 Steven Topik et al., eds., From Silver to Cocaine, 14.

3 Steven Topik et al., eds., From Silver to Cocaine, 5 and 18 [See reference mark no. 15].

4 Insituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE), "Tabela 3- Efetivo dos rebanhos de grande porte em 31.12, segundo as Grandes Regiões e as Unidades da Federação-2011", Produção da Pecuária Municipal 39 (2011): 30, accessed May 2013, <ftp://ftp.ibge.gov.br/Producao_Pecuaria/Producao_da_Pecuaria_Mu-nicipal/2011/tabelas_pdf/tab03.pdf>; "Exportações Brasileiras de Carne Bovina", Associação Brasileira das Indústrias Exportadoras de Carne (ABIEC), <http://www.abiec.com.br/download/Relatorioexportacao2012_ jan_out.pdf>, 2-5.

5 Until 1979, Mato Grosso was one state. In that year, the state was divided into two, with the south forming the state of Mato Grosso do Sul, while the north retained the original name. Unless otherwise indicated, the discussion here refers primarily to the south.

6 A close comparison from a slightly earlier period is the example of the neighboring state of Goiás. See David McCreery, Frontier Goiás, 1822-1889 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006), 130-154.

7 IBGE, Repertório Estatística do Brasil. Quadros Retrospectivos N.° 1 (Separata do Anuário Estatístico do Brasil- Ano v- 1939/1940), vol. 1 (Rio de Janeiro: IBGE, 1986), 14, 120 and 124; IBGE, Anuário estatístico do Brasil, 19081912 (Rio de Janeiro: Typ. Nacional, 1912), 251; "Industria pastoril", in Relatório do vice-presidente Dr. José Joaquim Ramos Ferreira devia apresentar à Assembléia Legislativa Provincial de Matto Grosso, 2° legislatura de Setembro de 1887 (Cuiabá: n/p., 1887), n/p.; Ministerio da Agricultura, Industria e Commercio, Synopse do censo pecuário da república pelo processo indirecto das avaliações em 1912-1913 (resultados provisórios) (Rio de Janeiro: Typ. do Ministério da Agricultura, Indústria e Commercio, 1914), 36 and 62.

8 IBGE, Estatísticas Históricas do Brasil, Séries Económicas, Demográficas e Sociais de 1550 a 1985, vol. 3 (Rio de Janeiro: IBGE, 1987), 307-312, and 524; "Livestock, 1930-193?", in United States National Archives (USMA), Washington-United States, Record Group (RG) 166: Records of the Foreign Agricultural Service, Narrative Agricultural Reports, 1904-1954, entry 5, box 64, 1-3. This entry is misfiled and should be 1920-1925.

9 Mensagem dirigido pelo Dr. Caetano Manoel de Faria e Albuquerque, Presidente de Matto Grosso, Assembléa Legislativa, 15 de maio de 1916 (Cuiabá: Typ. Official, 1916), 26-31; Virgílio Corrêa Filho, A propósito do Boi pantaneiro (Rio de Janeiro: Pongetti e Cia., 1926), 55-58.

10 Mensagem dirigido à Assembléa Legislativa, 13 de maio de 1922, pelo Coronel Pedro Celestino Corrêa da Costa, Presidente do Estado (Cuiabá: Typ. Official, 1922), 38-41.

11 Paulo de Moraes Barros, "A crise da pecuaria", Revista da Sociedade Rural Brasileira 24 (1922): 326-327; R. R. Bradford [US. Consul in Rio de Janeiro], "Government Efforts to Reduce Cost of Living", Rio de Janeiro, February 12, 1925, in USNA, RG 166, entry 5, box 65, n/p.

12 S. Cardoso Ayala and Feliciano Simon, Album Graphico do Estado de Matto-Grosso (Corumbá/Hamburg: n/p., 1914), 67-68; A. M. Gothchalk [US. Consul General in Rio de Janeiro], "Historical Sketch of the Lloyd Brazileiro Steamship Line", Rio de Janeiro, May 11, 1917, in USNA, RG 32: Records of the US. Shipping Board, Sub-classified General Files, ea. 1916-1936, file 153; "Letters from Lloyd Brazileiro to the Minister of the Treasury", Rio de Janeiro, 28 January, 1893; 13 February, 1894; 9 August, 1895; and 30 April, 1896, in Arquivo Nacional do Rio de Janeiro (ANRJ), Rio de Janeiro-Brazil, Section Companhia Lloyd Brazileiro- diversos, 1893-1897, [ Links ] if1 n. 159

13 "Report by José Alvarez Sánchez Surga, 1° Vice-Intendente of Nioac to the Mato Grosso Secretario de Estado dos negocios do Interior", Nioac, 19 January, 1912, in Arquivo Publico do Estado de Mato Grosso (APMT), Cuiabá-Brazil, Documentos avulsos, data 1912-A; Virgílio Alves Corrêa, "Aos Fazendeiros", Revista da Sociedade Matto-Grossense de Agricultura 1 (1907): 28; Miguel Arrojado Ribeiro Lisboa, Oeste de S. Paulo, Sul de Mato-Grosso. Geologia, Indústria Mineral, Clima, Vegetação, Solo Agrícola, Indústria Pastoril (Rio de Janeiro: Typografia do "Jornal do Commercio", 1909), 157-158; J. T. Nabuco de Gouvêa, "A Navegação Brasileira no Paraguay" [Report from the Brazilian Minister in Paraguay to the Brazilian Minister of Foreign Relations], Asunción, October, 1928, in apmt, Documentos avulsos, lata 1928-C. Note: "lata" ("can" in Portuguese) is the term used by the apmt for some of its holdings.

14 S. Cardoso Ayala and Feliciano Simon, Album Graphico, 124-125; "Meza de Rendas de Corumbá, Registros de exportação, 1915, 1920, 1926", in apmt, Coletorias avulsas; "Collectoria da Villa de Porto Murtinho, Impostos de exportação, 1919", in APMT, Coletorias avulsas; "Collectoria Estadoal do Porto Murtinho, Registro de exportações, 1925", in APMT, Coletorias avulsas.

15 "Exposição de motivos da Associação comercial aos representantes de Mato Grosso no Congresso Nacional. Corumbá, 10 de maio de 1923", in apmt, Coletorias avulsas, lata 1923, cited in Lúcia Salsa Corrêa, "Corumbá: um núcleo comercial na fronteira de Mato Grosso (1870-1920)" (M.A. thesis, Universidade de São Paulo, 1980), 135-140, annexo 1 and 3; Antonio Carlos Simoens da Silva, Cartas Mattogrossenses (Rio de Janeiro: n/p., 1927), 28-29; "Notas", A Cidade, Corumbá, 27 March, 1923, 1.

16 "Noticias de Porto Murtinho - O Lloyd e o Commercio", A Noticia, Tres Lagoas, 17 April, 1924, 2; J. T. Nabuco de Gouvêa, 'A Navegação Brasileira no Paraguay", in apmt, Coletorias avulsas; Informações gerais do municipio de Corumbá (Corumbá: n/p., 1932), 17-19; Virgílio Corrêa Filho, Pedro Celestino (Rio de Janeiro: Z. Valverde, 1945), 242.

17 Dióres Santos Abreu, "Communicações entre o sul de Mato Grosso de o sudoeste de São Paulo. O comércio de gado", Revista de História 53 (1976): 191-214.

18 Demosthenes Martins, História de Mato Gross: os fatos, os governos, a economia (São Paulo: n/p., 1977), 167-170; Fernando de Azevedo, Um Trem Corre para o Oeste. Estudo sobre o Noroeste e seu papel no sistema de viação nacional (São Paulo: Livraria Martins, 1950), 108-111, and 144.

19 Fernando de Azevedo, Um Trem Corre, 108-111, and 249-250; Paulo Roberto Cimó Queiroz, Uma ferrovia entre dois mundos: a E.F. Noroeste do Brasil na primeira metade do século 20 (Bauru: EDUSC, 2004), 111-187.

20 Paulo Roberto Cimó Queiroz, Uma ferrovia, 321-328.

21 C. R. Cameron, "Through Matto Grosso", Bulletin of the Pan American Union 66 (1932): 158-160; Fernando de Azevedo, Um Trem Corre, 108-111, and 249-250.

22 "População", in Anuário estatístico do Brasil, 1908-1912, vol. I (Rio de Janeiro: Typ. da Estatística, 1913), 327-328; Prefeitura Municipal de Campo Grande, Relatório 1943 (Rio de Janeiro: Imprensa Nacional, 1944), 38; Ministério da Agricultura, Commercio e Obras Públicas, Recenseamento realizado em 1 de Setembro de 1920, vol. 4, parte 1 "População" (Rio de Janeiro: Typ. da Estatística, 1926), 408; IBGE, Recenseamento Geral do Brasil (1° de Setembro de 1940), Série Regional, Parte XXII - Mato Grosso, Censo Demográfico, Censos Económicos (Rio de Janeiro: Serviço Gráfico do IBGE, 1952), 51; S. Cardoso Ayala and Feliciano Simon, Album Graphico, 410; Ministério da Agricultura, Indústria e Commercio, Estudo dos fatores da Producção nos Municípios Brasileiros e condições economicas de cada um: Estado de Matto Grosso, Município de Campo Grande (Rio de Janeiro: Imprensa Nacional, 1929), 39.

23 Roger L. Heacock [US. vice-consul in São Paulo], "Foreign Holdings in Mato Grosso", São Paulo, 23 January, 1941, in USNA, RG 166, entry 5, box 20, No. 478; Antonio Carlos Simoens da Silva, Cartas Matogrossenses, 18; Virgílio Corrêa Filho, A propósito, 52-54; S. Cardoso Ayala and Feliciano Simon, Album Graphico, 292-294.

24 Mensagem dirigido pelo Dr. Caetano Manoel de Faria e Albuquerque, Presidente de Matto Grosso, à Assembléa Legislativa, 15 de maio de 1916 (Cuiabá: Typ. Official, 1916), 35 and 41.

25 Arlindo de Andrade, Erros da federação (São Paulo: n/p., 1934), 89; Virgílio Corrêa Filho, A propósito, 52-54; Mensagem dirigido à Assembléa Legislativa, 75-76.

26 Relatório do Município de Aquidauana, 1928 (São Paulo: n/p., 1929), 55-58; "Report by Jorge Bodstein Filho, president of the Aquidauana Municipal Council, to the President of Mato Grosso", Aquidauana, 14 February, 1929, in APMT, Documentos avulsos, lata 1929-F; Paulo Roberto Cimó Queiroz, Uma ferrovia, 411-418.

27 Arlindo de Andrade, Erros, 72-73; Paulo Roberto Cimó Queiroz, Umaferrovia, 399-411; Ministério da Agricultura, Indústria e Commercio, Estudo dos Factores da Producção nos Municípios Brasileiros e Condições economicas de cada um. Estado de MattoGrosso, Município de Corumbá (Rio de Janeiro: Ministério da Agricultura, 1924), 17; John Hubner II [US. Vice-Consul in São Paulo], "Rumored Plan for the Encouragement of Immigration of Cattle Raisers into the State of Matto Grosso", São Paulo, 9 August, 1938, in USNA, Reports of the US. Consuls in Brazil, 1910-29, microfilm m-519, roll 27, No. 832.52 am3/22.

28 Fernando de Azevedo, Um Trem Corre, 182-185, and 191-196; Paulo Roberto Cimó Queiroz, Uma ferrovia, 347358, and 395-411; Carlos Araujo, "A exportação dos bovinos", Jornal do Commercio 14 (1934): 1 and 4; "A regula-risação do trafego da E.F. Noroeste", Jornal do Commercio 14 (1934): 1 and 4; Evolução histórica sul Mato Grosso (São Paulo: Organização Simões, n/d.) 133.

29 Virgílio Alves Corrêa, "Aos Fazendeiros", 13-20, and 28-31.

30 Mensagem dirigido pelo Dr. Caetano Manoel de Faria e Albuquerque, Presidente de Matto Grosso, Assembléa Legislativa, 15 de maio de 1916 (Cuiabá: Typ. Official, 1916), 15-18 and 89-97; A Feira de Gado de Tres Lagoas, Creação e installação (São Paulo: n/p., 1922), 70.

31 Mensagem pelo Dr. Joaquim A. da Costa Marques, Presidente do Estado à Assembléa Legislativa, 13 de maio de 1913 (Cuiabá: Typ. Official, 1913), 33-34; S. Cardoso Ayala and Feliciano Simon, Album Graphico, 290-292.

32 Feira de Gado de Tres Lagoas, Creação e installação, 7-10, and 23.

33 Bruno Garcia, "A Cia. Feira de Gado, tem nos beneficiado? Não", A Noticia, Tres Lagoas, 6 August, 1925, 1; A. G., "Com a Feira", A Noticia, 13 August, 1925, 6; Mensagem dirigido à Assembléa Legislativa em 13 de maio de 1926pelo Dr. Mario Corrêa da Costa, Presidente do Estado de Mato Grosso (Cuiabá: Typ. Official, 1926), 98-100; Carlos Gomes Borralha, "Relatorio da Secretaria da Agricultura, Industria, Commercio, Viação e Obras Publicas, referente ao exercicio de 1921", in APMT, Documentos avulsos, lata 1921-C.

34 "Posto de Assistencia Veterinaria", Gazeta de Commercio 7, Tres Lagoas, 16 January, 1927, 1; Mensagem dirigido pelo Dr. Caetano Manoel de Faria e Albuquerque, Presidente de Matto Grosso, Assembléa Legislativa, 15 de maio de 1916 (Cuiabá: Typ. Official, 1916); Mensagem à Assembléa Legislativa, 13 de maio de 1927, por Mario Corrêa, Presidente do Estado de Mato Grosso (Cuiabá: Typ. Official, 1927), 155; "Letter from the director of the Fazenda Modelo de Criação, A. Teixeira Vianna, to the president of Mato Grosso", Campo Grande, 2 August, 1925, in APMT, Documentos avulsos, lata 1925-B; Mensagem apresentado à Assembléa Legislativa pelo Presidente de Mato Grosso, Dr. Annibal Toledo, 13 de maio de 1930 (Cuiabá: Typ. Official, 1930), 18-24.

35 Arlindo de Andrade, Erros, 77; Dolor F. Andrade, Mato Grosso e a sua pecuaria (São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo, 1936), 8; "Histórico", Embrapa. Gado de Corte, <http://www.cnpgc.embrapa.br/index.php?pagina=unidade/ historicounidade.htm>.

36 S. Cardoso Ayala and Feliciano Simon, Album Graphico, 288-289; Eduardo Cotrim, A Fazenda Moderna: Guia do Criador de Gado Bovino no Brasil (Brussels: Typ. V. Verteneuil et L. Desmet, 1913), 135-145; Miguel Arrojado Ribeiro Lisboa, Oeste de S. Paulo, 136-137; Otavio Domingues and Jorge de Abreu, Viagem de estudos, 17.

37 Miguel Arrojado Ribeiro Lisboa, Oeste de S. Paulo, 140; J. Carlos Travassos, Industria pastoril: conferencia rea-lisada na Sociedade Nacional de Agricultura (Rio de Janeiro: Sociedade Nacional de Agricultura, 1898), 35-36; Fernand Ruffier, Dos meios de melhorar as raças nacionaes. Primeira Conferencia Nacional de Pecuária (Rio de Janeiro: n/p., 1917), 58-59 and 65-66. For a revealing discussion of the experience in Rio Grande do Sul just a few years previously, see Stephen Bell, Campanha Gaúcha: A Brazilian Ranching System, 1850-1920 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998), 99-117.

38 Virgílio Corrêa Filho, A proposito, 48-50; Paulo de Moraes Barros, O sul de Matto Grosso e a pecuaria (São Paulo: Sociedade Rural Brasileira, 1922), 12 and 17-21.

39 Maria Antonia Borges Lopes and Eliane M. Marquez Rezende, ABCZ, 50 Anos de História e Estorias (Uberaba: Associação Brasileira de Criadores de Zebú, 1984), 31; Alberto Alves Santiago, O zebu na Índia, no Brasil e no mundo (Campinas: Instituto Campineiro de Ensino Agrícola, 1985), 119-134, 143 and 168-171.

40 Dolor F. Andrade, Mato Grosso, 6; Rodolpho Endlich, "A criação do gado vaccum nas partes interiores da America do Sul", Boletim da Agricultura 3: 12 (1902): 745; Paulo Coelho Machado, A Rua Velha; Pelas ruas de Campo Grande, vol. I (Campo Grande: Tribunal de Justiça de Mato Grosso do Sul, 1990), 93-95.

41 Miguel Arrojado Ribeiro Lisboa, Oeste de S. Paulo, 152-153; Paulo Coelho Machado, A Rua Velha, 93.

42 Miguel Arrojado Ribeiro Lisboa, Oeste de S. Paulo, 139.

43 Fernand Ruffier, Dos meios, 39-42, 58-59, 65-66 and 72-78; Antonio da Silva Neves, Primeira conferencia nacional de pecuária; origem provável das diversas raças que povoam o territorio patrio, alimentação racional, hygiene animal (São Paulo: n/p., 1918), 58-59 and 63-68.

44 Fernand Ruffier, Guerra ao Zebú, um pouco de agua fria... (Castro: n/p., 1919), 7-10; Octávio Domingues, O Zebu, sua reprodução e multiplicação dirigida (São Paulo: Nobel, 1971), 40 and 43.

45 Fernand Ruffier, Guerra ao Zebú, 18-28.

46 Virgílio Corrêa Filho, A propósito, 44-46; "A creação em Matto Grosso", Brasil Agrícola 1 (1916): 362-363; Gervásio Leite, O gado na economia matogrossense (Cuiabá: Escolas Profissionais Salesianos, 1942), 9-11; Antonio Carlos de Oliveira, Economia pecuária do Brasil Central: Bovinos (São Paulo: Departamento Estadual de Estatística de São Paulo, 1941), 184-185.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Archives:

Arquivo Nacional do Rio de Janeiro (ANRJ), Rio de Janeiro-Brazil. Section Companhia Lloyd Brazileiro- diversos, 1893-1897.

Arquivo Publico do Estado de Mato Grosso (APMT), Cuiabá-Brazil. Documentos avulsos and Coletorias avulsas. [ Links ]

United States National Archives (USNA), Washington-United States. Records of the US. Shipping Board, Sub-classified General Files, ea. 1916-1936, (RG) 32; Records of the Foreign Agricultural Service, Narrative Agricultural Reports, 1904-1954, (RG) 166. [ Links ]

Newspapers:

A Cidade. Corumbá, 1923. [ Links ]

A Noticia. Tres Lagoas, 1924-1925. [ Links ]

Gazeta de Commercio. Tres Lagoas, 1927. [ Links ]

Jornal do Commercio. Campo Grande, 1934. [ Links ]

Printed Primary Sources:

"A creação em Matto Grosso". Brasil Agrícola 1 (1916): 362-363. [ Links ]

A Feira de Gado de Tres Lagoas. Creação e installação. São Paulo: n/p., 1922. [ Links ]

Andrade, Arlindo de. Erros da federação. São Paulo: n/p., 1934. [ Links ]

Andrade, Dolor F. Mato Grosso e a sua pecuaria. São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo, 1936. [ Links ]

Ayala, S. Cardoso and Feliciano Simon. Album Graphico do Estado de Matto-Grosso. Corumbá/Hamburg: n/p., 1914. [ Links ]

Barros, Paulo de Moraes. "A crise da pecuaria". Revista da Sociedade Rural Brasileira 24 (1922): 324-328. [ Links ]

Barros, Paulo de Moraes. O sul de Matto Grosso e a pecuaria. São Paulo: Sociedade Rural Brasileira, 1922. [ Links ]

Cameron, C. R. "Through Matto Grosso". Bulletin of the Pan American Union 66 (1932): 155-168. [ Links ]

Corrêa Filho, Virgílio. A propósito do Boi pantaneiro. Rio de Janeiro: Pongetti e Cia., 1926. [ Links ]

Corrêa, Virgílio Alves. "Aos Fazendeiros". Revista da Sociedade Matto-Grossense de Agricultura 1 (1907): 13-31. [ Links ]

Cotrim, Eduardo. A Fazenda Moderna: Guia do Criador de Gado Bovino no Brasil. Brussels: Typ. V. Verteneuil et L. Desmet, 1913. [ Links ]

Endlich, Rodolpho. "A criação do gado vaccum nas partes interiores da America do Sul". Boletim da Agricultura 3: 12 (1902): 740-746, 810-821. [ Links ]

IBGE. Anuário estatístico do Brasil, 1908-1912. Rio de Janeiro: Typ. Nacional, 1912. [ Links ]

IBGE. Estatísticas Históricas do Brasil, Séries Econômicas, Demográficas e Sociais de 1550 a 1985, volume 3. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE, 1987. [ Links ]

IBGE. Recenseamento Geral do Brasil (1° de Setembro de 1940), Série Regional, Parte XXII - Mato Grosso, Censo Demográfico, Censos Económicos. Rio de Janeiro: Serviço Gráfico do IBGE, 1952. [ Links ]

IBGE. Repertório Estatística do Brasil. Quadros Retrospectivos. N.° 1 (Separata do Anuário Estatístico do Brasil-Ano V- 1939/1940), volume 1. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE, 1986. [ Links ]

Leite, Gervásio. O gado na economia matogrossense. Cuiabá: Escolas Profissionais Salesianos, 1942. [ Links ]

Lisboa, Miguel Arrojado Ribeiro. Oeste de S. Paulo, Sul de Mato-Grosso. Geologia, Indústria Mineral, Clima, Vegetação, Solo Agrícola, Indústria Pastoril. Rio de Janeiro: Typografia do "Jornal do Commercio", 1909. [ Links ]

Mensagem à Assembléa Legislativa, 13 de maio de 1927, por Mario Corrêa, Presidente do Estado de Mato Grosso. Cuiabá: Typ. Official, 1927. [ Links ]

Mensagem apresentado à Assembléa Legislativa pelo Presidente de Mato Grosso, Dr. Annibal Toledo, 13 de maio de 1930. Cuiabá: Typ. Official, 1930. [ Links ]

Mensagem dirigido à Assembléa Legislativa em 13 de maio de 1926 pelo Dr. Mario Corrêa da Costa, Presidente do Estado de Mato Grosso. Cuiabá: Typ. Official, 1926. [ Links ]

Mensagem dirigido à Assembléa Legislativa, 13 de maio de 1922, pelo Coronel Pedro Celestino Corrêa da Costa, Presidente do Estado. Cuiabá: Typ. Official, 1922. [ Links ]

Mensagem dirigido pelo Dr. Caetano Manoel de Faria e Albuquerque, Presidente de Matto Grosso, à Assembléa Legislativa, 15 de maio de 1916. Cuiabá: Typ. Official, 1916. [ Links ]

Mensagem pelo Dr. Joaquim A. da Costa Marques, Presidente do Estado à Assembléa Legislativa, 13 de maio de 1913. Cuiabá: Typ. Official, 1913. [ Links ]

Ministério da Agricultura, Commercio e Obras Públicas. Recenseamento realizado em 1 de Setembro de 1920, vol. 4, parte 1 "População". Rio de Janeiro: Typ. da Estatística, 1926. [ Links ]

Ministério da Agricultura, Indústria e Commercio. Estudo dos Factores da Producção nos Municípios Brasileiros e Condições economicas de cada um: Estado de Matto Grosso, Município de Corumbá. Rio de Janeiro: Ministério da Agricultura, 1924. [ Links ]

Ministério da Agricultura, Indústria e Commercio. Estudo dos fatores da Producção nos Municípios Brasileiros e condições economicas de cada um: Estado de Matto Grosso, Município de Campo Grande. Rio de Janeiro: Imprensa Nacional, 1929. [ Links ]

Ministério da Agricultura, Industria e Commercio. Synopse do censo pecuário da república pelo processo indirecto das avaliações em 1912-1913 (resultados provisórios). Rio de Janeiro: Typ. do Ministério da Agricultura, Indústria e Commercio, 1914. [ Links ]

Neves, Antonio da Silva. Primeira conferencia nacional de pecuária; origem provável das diversas raças que povoam o territorio patrio, alimentação racional, hygiene animal. São Paulo: n/p., 1918. [ Links ]

Oliveira, Antonio Carlos de. Economia pecuária do Brasil Central: Bovinos. São Paulo: Departamento Estadual de Estatística de São Paulo, 1941. [ Links ]

Prefeitura Municipal de Campo Grande. Relatório 1943. Rio de Janeiro: Imprensa Nacional, 1944. [ Links ]

Relatório do Município de Aquidauana, 1928. São Paulo: n/p., 1929. [ Links ]

Relatório do vice-presidente Dr. José Joaquim Ramos Ferreira devia apresentar à Assembléia Legislativa Províncial de Matto Grosso, 2° legislatura de Setembro de 1887. Cuiabá: n/p., 1887. [ Links ]

Ruffier, Fernand. Dos meios de melhorar as raças nacionaes. Primeira Conferencia Nacional de Pecuária. Rio de Janeiro: n/p., 1917. [ Links ]

Ruffier, Fernand. Guerra ao Zebú, um pouco de agua fria... Castro: n/p., 1919. [ Links ]

Silva, Antonio Carlos Simoens da. Cartas Mattogrossenses. Rio de Janeiro: n/p., 1927. [ Links ]

Travassos, J. Carlos. Industria pastoril: conferencia realisada na Sociedade Nacional de Agricultura. Rio de Janeiro: Sociedade Nacional de Agricultura, 1898. [ Links ]

Interview:

Interview with Machado, Paulo C. Campo Grande, May, 1990. [ Links ]

Secondary Sources

"Exportações Brasileiras de Carne Bovina". Associação Brasileira das Indústrias Exportadoras de Carne (ABIEC). <http://www.abiec.com.br/download/Relatorioexportacao2012_jan_out.pdf> [ Links ].

"Histórico". Embrapa. Gado de Corte. <http://www.cnpgc.embrapa.br/index.php?pagina=unidade/ historicounidade.htm> [ Links ].

Abreu, Dióres Santos. "Communicações entre o sul de Mato Grosso de o sudoeste de São Paulo. O comércio de gado". Revista de História 53 (1976): 191-214. [ Links ]

Azevedo, Fernando de. Um Trem Corre para o Oeste; estudo sobre a Noroeste e seu papel no sistema de viação nacional. São Paulo: Livraria Martins, 1950. [ Links ]

Bell, Stephen. Campanha Gaúcha: A Brazilian Ranching System, 1850-1920. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998. [ Links ]

Corrêa Filho, Virgílio. Pedro Celestino. Rio de Janeiro: Z. Valverde, 1945. [ Links ]

Corrêa, Lúcia Salsa. "Corumbá: um núcleo comercial na fronteira de Mato Grosso (1870-1920)". M.A. Thesis, Universidade de São Paulo, 1980. [ Links ]

Domingues, Octávio. O Zebu, sua reprodução e multiplicação dirigida. São Paulo: Nobel, 1971. [ Links ]

Domingues, Otavio and Jorge de Abreu. Viagem de estudos à Nhecolandia. Rio de Janeiro: Instituto de Zootecnia, 1949. [ Links ]

Evolução histórica sul Mato Grosso. São Paulo: Organização Simões, n/d. [ Links ]

IBGE. "Tabela 3- Efetivo dos rebanhos de grande porte em 31.12, segundo as Grandes Regiões e as Unidades da Federação-2011". Produção da Pecuária Municipal 39 (2011): 30. <ftp://ftp.ibge.gov.br/Producao_Pecuaria/Producao_da_Pecuaria_Municipal/2011/tabelas_pdf/tab03.pdf> [ Links ].

Lopes, Maria Antonia Borges and Eliane M. Marquez Rezende. ABCZ, 50 Anos de História e Estorias. Uberaba: Associação Brasileira de Criadores de Zebú, 1984. [ Links ]

Machado, Paulo Coelho. A Rua Velha; Pelas ruas de Campo Grande, volume 1. Campo Grande: Tribunal de Justiça de Mato Grosso do Sul, 1990. [ Links ]

Martins, Demosthenes. História de Mato Grosso: os fatos, os governos, a economia. São Paulo: n/p., 1977. [ Links ]

McCreery, David. Frontier Goiás, 1822-1889. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006. [ Links ]

Queiroz, Paulo Roberto Cimó. Uma ferrovia entre dois mundos: a E.F. Noroeste do Brasil na primeira metade do século 20. Bauru: EDUSC, 2004. [ Links ]

Santiago, Alberto Alves. O zebu na Índia, no Brasil e no mundo. Campinas: Instituto Campineiro de Ensino Agrícola, 1985. [ Links ]

Topik, Steven, Carlos Marichal and Zephyr Frank, editors. From Silver to Cocaine: Latin American Commodity Chains and the Building of the World Economy, 1500-2000. Durham: Duke University Press, 2006. [ Links ]