Introduction

On 13 December 1474, when there was still no notion of the existence of the huge American continent that would later be covered by the Hispanic Empire of the Habsburgs and Bourbons, a young Isabella was acclaimed and took her oath as Queen of Castile in Segovia.1 The protocol followed in the ceremony was very simple: the raising of banners on a stage in the main city square and the monarch taking an oath in the presence of representatives of the realm to uphold the laws to renew the pact. There was no architecture other than the stage and no decoration other than the banners. The decoration for the ceremony was limited to representing the queen and her kingdom symbolically through their heraldic arms, the banners and the insignia, particularly the sword. The queen and the others present, however, were very richly dressed and the monarch was protected with an elaborate canopy during the procession from the stage to the church. The same oath was repeated in other cities of the kingdom albeit in the absence of Isabella. From that time on, the chronicles would become more abundant, describing the oath ceremonies in the different cities and the richness of the ritual and decorations. As is well known, a whole new genre known as accounts of festivities developed out of this as additional elements were incorporated into the ritual: the royal entrance, the civic and public parade, and the use of the Royal Standard as a symbol of the royalty.2

For more than a century later, artistic simplicity would continue to be the general tone in the proclamations of the Hispanic monarchs. All this would change from the 17th century onwards, however, when elaborate ephemeral architecture and decoration invaded the oath stages and the facades in the squares and streets along the route of the Royal Standard. The Villa of Madrid, established as the capital of the Crown from 1561 onwards, became the quintessential festive city of the Spanish Court. The urban planning became more important than ever before with royal welcomings, as the king and the city organized the processional tour of the main streets and squares, mainly along the axis from the Palacio Real to the Prado de San Jerónimo, which benefitted from urban and architectonic improvements. The royal event consisted of two essential moments: the triumphal or allegorical procession and the exaltation act or reception ceremony.3

In addition to the royal welcomings, one other 17th century festivity that united urban glory and the processional tour of the streets with the importance of the squares was the exaltation or pledging of the king. Streets like Calle Mayor, which became the city's main thoroughfare when Philip II regularized it from Puerta del Sol to its junction with Plaza del Palacio, were prominent in this area. Carrera de San Jerónimo, which extended from the monastery to Puerta del Sol, was also important since it was the site of several religious institutions empowered by the crown such as San Felipe el Real, Hospital de la Corte and Convento de la Victoria. Royal announcements were made on each of the four stages built in the main squares of Madrid: Plaza Mayor, Plazuela de Palacio and Plazuela de la Villa (also known as Plazuela del Salvador), and Plaza de las Descalzas Reales. The processional tour started in Casas del Ayuntamiento with the Royal Ensign and his convoy carrying the banner.4

The decorations in the squares and streets of Madrid and in the cities of the Empire were created to display the ideological image of the monarch, illustrating his virtues, his duties to his subjects and the hopes and desires they deposited in their new king. However, from that time onward, the composite monarchy system of the Spanish Crown gave rise to a unique phenomenon in royal proclamations: manifestation of the identity elements of each kingdom through art. In other words, at the moment when the pact between different kingdoms and the monarch was renewed, i.e. during the acclamation ceremonies, in parades, in the iconographic programs of the oath stages and other miscellaneous decoration, the identity elements of the kingdoms and their political and social assertions were expressed via a common language of allegory and emblems. This was done in spectacular fashion in distant kingdoms or dominions and in those which, due to political circumstances, had special freedoms or privileges they were either trying to preserve or to recover, thus reinforcing or constructing symbols of their identity thanks to these ceremonies.

It is difficult to find engravings of the ephemeral architecture created for royal oath ceremonies of the Hispanic monarchy in the 16th and 17th centuries. This void is perhaps related to the fact that the Habsburgs had a very deep-rooted concept of legitimacy, which appeared in other circumstances and various media to reinforce the ideological and devotional message of their dynasty. Nonetheless, the Bourbons constantly had to resort to proclaiming their legitimate rights over the territories of the Hispanic monarchy by using the resources of allegory and mythology in portraits and propaganda images, especially on the stages where the royal oaths were taken, thereby reinforcing the idea of good governance and often establishing links to the Habsburgs. In this text we attempt to analyze some examples of oath ceremonies in which the idiosyncratic features of the different kingdoms were displayed in the ephemeral decoration created for the occasion.5

Furthermore, in the Spanish Monarchy the heir to the throne was sworn in during the royal oath ceremonies. This ritual took place when the prince was still an infant, only one or two years of age, but after the risk of early death had passed. For example, Philip II was sworn in as heir in 1528 when he was one year old in a simple ceremony in which nobles, prelates and representatives of the cities represented at Court pledged loyalty and swore homage.6 These ceremonies were more complex in Aragon since the heir was not sworn in there until coming of legal age. Therefore, Philip II would not be sworn in at the Courts of Monzón and Zaragoza until 1542, when it was done in two separate rituals because the swearing in was reciprocal in the former, but not in the latter. The cities also organized a formal welcoming for this occasion. Their particular rituals and decorations acclaimed their own identity as city and realm. The welcoming was especially magnificent in the tour of the Netherlands, where more than thirty cities welcomed the prince for his oath in 1549 and 1550.7 Upon his return, he was sworn in at the Court of Navarre in 1551 in the city of Tudela.8

Nevertheless, these oaths did not necessarily mean that succession would take place without issues later; some territories thus required the presence of the king in order to exalt him as the monarch. During the 17th century, the establishment of the Etiquette of the Palace by Philip IV and, especially, the floor plans drawn up by Juan Gómez de Mora give us a detailed idea of the protocol followed in the royal oath ceremony during that period. Unlike the royal exaltation, which took place on the streets of the cities without the presence of the new king, the prince's oath occurred inside Los Jerónimos church in the exclusive presence of the royal family accompanied by prelates, nobles with their first-born offspring, court representatives, council members and servants of the king. Fernando Marías has analyzed this ceremony and the possible portraits of oath-taking ceremonies in a magnificent study that I reference below.9

This article explores the idiosyncratic features of different territories ruled by the Spanish Monarchy that were used in the ephemeral decorations for the oath ceremonies as way to assert a claim for their past and their future. In a composite monarchy, the term John Elliot coined to refer to the union of the Spanish Kingdoms, it was very important to communicate to the King what they would expect from him in the future as well as the need to not forget the features of their identity.10 In that sense, we analyze the idiosyncratic claims represented in the decorations in different territories and centuries. First of all, we consider Portugal, which was incorporated into the Spanish Monarchy as a New Kingdom at the end of the 16th century and lost in the 17th century; secondly, the Viceroyalty of New Spain, where mestizo idiosyncratic elements were very important in the 18th century; and finally, the Crown of Aragon, the identity elements of which were eliminated after the War of the Spanish Succession.

The Kingdom of Portugal

The first example we are going to deal with is that of the Kingdom of Portugal because it was one of the earliest. Once the genealogical issue regarding inheritance of the kingdom had been cleared up, Philip II prepared to take the oath of his new kingdom and to swear to respect the rights of the Portuguese. Perhaps because the conflict had been resolved through dynastic claim, the issue of genealogical legitimacy was very evident in the ephemeral decoration for royal visits to Portugal to be sworn in before the Courts. On his 1581 visit, Philip II entered Portugal via the town of Santarem, where he was received with suspicion. The proclamation and oath ceremony took place in the town of Tomar on 16 April, while his son, Prince Diego, was sworn in as heir.11

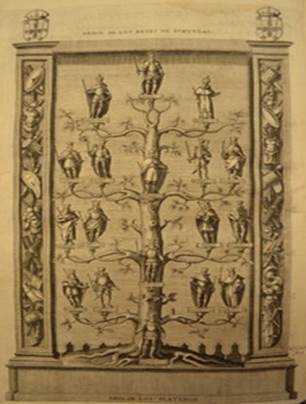

On 29 June that year, Philip triumphantly entered the city of Lisbon, the capital of the kingdom. Because of its commercial nature that brought together different nations, the urban festivities in Lisbon became "a shop window for the elites of foreign merchants, powerful craft guilds, religious congregations, the regular orders and, of course, the Portuguese monarchy."12 As Laura Fernández has highlighted, on that occasion the decorations celebrated Iberian union and the two trans-oceanic empires that stretched all around the world.13 Although there were many allusions to Castile, they were moderate compared to those referring to the outstanding role of the city and kingdom that were receiving the king: i.e. Lisbon and Portugal. Among the many decorations and arches -more than fifteen altogether- we may highlight the Arch of the Germans, one of the few made by other nations present in the city. We are interested in the face it showed to the city, dedicated to Prince Diego, who was supposed to remain as governor of the kingdom. One of the allegorical figures it portrayed, that of Providence, bore inscriptions alluding to the fact that the monarchy had to respect the privileges of Portuguese cities,14 and to defend and protect the kingdom, as well as to propagate the Catholic faith (Image 1). Beside that figure, the allegory of Lusitania was portrayed kneeling before the figure of the prince, offering him a golden ring and the coat of arms of Portugal and the Algarve as a symbol of obedience. Thus, at the same time the prince was reminded that he must comply with his obligations of defense and respect, the German merchants living in Lisbon offered their submission.

Source: Unknown engraver, "Frontispice," in Alfonso Guerreiro, Das Festas que se fizeram na cidade de Lisboa, na entrada del Rey D. Philippe primeiro de Portugal (Lisbon: Francisco Correa, 1581), 1.

Image 1 Frontispice

In this image, in front of the Ribeira gates on the Terreiro de Paço, various columns were set up, adorned with decorations that included allegories of the Portuguese territories (Goa, Cananor, Cochim, Chaul, Dio in Cambodia, Ceylon, Malacca, Hormuz and Ethiopia), also depicted as offering their riches to the monarch. Two figures, corresponding to the East and West Indies respectively, called for the union of the two kingdoms. An arch in the same place, at the Portas da Ribeira, showed an allegory of Lisbon with her breast uncovered as a symbol of surrender, carrying a boat and flanked by Saint Anthony and Saint Vincent, the patron saints of the city. The Silversmith's Arch displayed a family tree showing the genealogy of the kings of Portugal starting with Alfonso VI of Castile. In this way, the people of Lisbon offered the monarch legitimately inherited dominion over a worldwide empire.

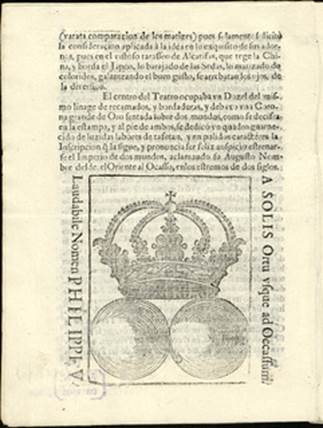

Moreover, Philip II's son, Philip III, also travelled to Portugal in 1619 to renew the pact with the Cortes and have the kingdom pledge its loyalty to his heir, the future Philip IV. But by then the Portuguese were already unhappy about the breach of the pledge of 1581 so they held the reception in the absence of the monarch, thus asserting Lisbon's right to be the capital of the kingdom.15 The outstanding features in the decoration on the ephemeral arches once again included the allegorical figure of Lisbon extolling the virtues of the city and of the Portuguese and Spanish monarchs as conquerors and lords of the world, culminating in an image of Philip III dominating the globe. The Silversmith's Arch once again represented the Portuguese monarchs on a magnificent silver-plated family tree laden with full-length figures of the kings, thus evoking dynastic right (Image 2).

Source: Justus Schorquens, engraver, "Silversmith's Arch," in Ioâo Baptista Lavanha, Viagem da Catholica Real Magestade del Rey D. Filipe II N. S. ao reyno de Portugal E rellaxâo do solene recebimento que nelle se lhe fez S. Magestade (Madrid: Thomas Iunti, Royal printer, 1622), 28.

Image 2 The Silversmith's Arch

However, as Fernández has rightly noted, the inclusion of monarchs like John I and Manuel I on the Arch of the Portuguese was perhaps intended mainly as a protest.16 In fact, although the Castilian kings were represented on that arch, the Portuguese monarchs were clearly portrayed as being superior. In addition, allusions to Discord on the Arch of the Flemish distinguished between loyal and rebellious provinces, showing the growing discontent of some territories of the composite monarchy. Portugal, specifically the city of Lisbon, thus presented itself on these occasions as a territory and city extolling its monarchy, history and commercial and territorial power in the face of the arrival of a new dynasty, with submission based on the monarch's pact with the Portuguese Cortes.

Both these examples of royal visits in 1581 and 1619 demonstrate that the city of Lisbon used ephemeral decorations to renew the loyalty vows to its king, but also to assert its claim for its own identity issues, reminding the king that he was just one branch of the Portuguese genealogical tree. In the same sense, the city, as the capital of the Kingdom of Portugal appealed to his global power in both cases and reminded him that he must protect and respect the kingdom. As will be seen below, identity claims were stronger in the Viceroyalty of New Spain than they were in the Iberian Peninsula.

The American Viceroyalties

The study of the Bourbon dynasty festivals in the Viceroyalty of New Spain in Latin America makes it possible to see the rhetoric of identity and the role of history much more clearly than in other Hispanic territories.17 While the sumptuary and hybrid aspects of festivals during the Habsburg period revealed a policy of promoting adherence to the Habsburg dynasty and its ideology based on the instances of viceroyal power, that changed in the 17th century due to the incipient emergence of Creolism. In the 18th century, this became open differentiation between an American and a peninsular identity, which would be transformed in the 19th century into nationalism and pro-autonomy and independence movements. That development led to the use of decoration to assert the identity of Americans through allegories of America, New Spain and Peru through representations of the pre-Hispanic emperors, thus establishing continuity with the Habsburgs and the Bourbons.18

For example, in the 18th century and with the Bourbons having assumed the Spanish throne, Philip V was sworn in by the governing council of Mexico City.19 The royal decree ordering the ceremony was dated 22 November 1700 and the festivities took place more than three months later on 4 April, the feast of the Incarnation. In addition to an item from the minutes of the City Council, we also have a printed account of the festival written by Gabriel de Mendieta, the chief scribe of the council.20 The main stage was larger this time than those set up on other occasions: thirty yards long and fifteen yards wide, with a cover supported by six Solomonic columns forming five arches at the front and two at the side. The entire stage was dressed with embroidered cloths. Two golden lions on a white background were embroidered on the cover of the structure, which was made of carmine velvet. A canopy was hung in the center of the platform, under which there were two globes topped by a huge crown with an eagle, and an embroidered on it at the bottom proclaiming Philip V from East to West (Image 3).

Once the solemn oath had been taken, the globes and the eagle opened up, the latter tearing its breast like a phoenix to release birds, rabbits and other small animals. Flanking the crowned globes were two matrons, one representing Castile and the other, dressed like an Indian, representing New Spain. Two winged genies flying high above made the ritual proclamation of Castile and New Spain, comparing the two kingdoms and the dependence of America on Castile. This example shows that not even the change of dynasty nor the long Spanish dominion affected the presence of the allegory of New Spain, dressed like an Indian, as a territory in submission to the Kingdom of Castile.

Source: "Crowned Globes," in Relación de los actos y fiestas celebrados en la ciudad de Méjico con motivo de la proclamación de Felipe V. Escribiala D. Gabriel de Mendieta Revollo, Hijo de esta Ciudad Imperial de México, y Escribano Mayor de su Ayuntamiento (Mexico: Juan Joseph Guillena rrascoso, 1701).

Image 3 Crowned Globes

Assertions of Mexican identity were also present in the acclamation of Fernando VI in Mexico City. There are more printed accounts of the festivities for this oath ceremony than for almost any other in the entire viceroyalty, giving us information on those taking place in Mexico City, Merida, Guadalajara and Durango.21 In the case of Mexico City, the festivities were reported by José Mariano de Abarca, who wrote very detailed descriptions of everything related to the celebrations.22 The iconographic program for the occasion focused on the solar parallels between the Sun and the Moon and Fernando VI and Barbara of Braganza.23 It took the form of three stages set up by the artists Francisco Martínez and Juan de Espinosa, who decorated them with the coats of arms of the kingdoms, allegories of the different parts of the world, and statues alluding to six planets referring to a seventh planet presented in the form of a portrait of the monarch. In addition, a triumphal arch with three bodies was built across from the palace, decorated with images of painters from ancient times, such as Apelles and Timanthes, and of Roman emperors.24 Mínguez has also highlighted two of the spectacles organized for the festivities: the pig dealers' float simulating the hill of Chapultepec and the Aztec kings, as well as the four triumphal arches erected by the Royal Medical Tribunal in the cemetery of the church of the Hospital de La Concepción y Jesús Nazareno.

This American identity was not only fully assumed for the proclamation of Charles III on 25 June, 1760, it was also asserted to call on the monarchy to defend its territories. The Mexians called on the monarch to protect their religion and homeland, and to promote education within it. Agustín de Castro's account telling of the triumphal arch put up opposite the archbishop's palace, created by the leading painter Miguel Cabrera, is significant in this sense.25 The arch was composed of three parts, with the lateral canvases of the first section presenting a view in the shape of porticoes forming a semicircular theatre. The iconographic program revolved around the royal commitment to the Empire of the Indies, despite many attacks against it by foreign powers. It therefore produced a medallion portraying Charles III being sustained by Religion, Politics and Valor. There is an allegorical figure of Providence in flight pointing to the Mexican coast, where the figure of a matron represents the Holy Church of Mexico, accompanied by Loyalty and Piety and surrounded by the Spanish and American nations.

Two more figures representing religion appear at the base, with the Holy Cross evangelizing an Indian, and Politics, wearing a costume made up of eyes and ears, overcoming the ignorance of the Indians. Religion, education and defense were the issues that concerned Americans within a historical context of internal reforms and threats from abroad. To give a peninsular example to compare what happened in Spain with New Spain, the city of Granada also solemnly swore loyalty to Carlos III.26 Even though the Kingdom of Granada had been the last to join the Spanish monarchy, its idiosyncratic features were almost entirely lost in the 18th century and there is no indication of an attempt to reclaim any feature of its Islamic past in the iconographic program of these festivities. The kingdom had been fully integrated into Castile by then, and there was only the fruit of the pomegranate to represent its configuration as a territory.

As a final point of comparison with New Spain, the Viceroyalty of Peru also asserted the idiosyncratic features of its inhabitants and their historical past in its festivities. On 17 October 1666 they swore an oath to King Charles II.27 A square stage was set up in a space marked off with barriers opposite the Viceroy's Palace and a complex and very rich architectural structure was placed on top. In the center there was a portrait of the monarch and his throne, together with an image of the Inca emperor dressed in the traditional mascapacha feathered suit with his royal insignia and the sun on his chest. The emperor is depicted offering Charles II a golden crown while his wife, the Coya, offers the young monarch a crown of flowers. The engraving by the Mercedarian Friar Cristóbal Cabellero includes an image of this magnificent creation (Image 4).

As in the case of Portugal, genealogy was appealed to in New Spain and Peru as well, where it was done by representing the Aztec and Inca emperors as predecessors of the Spanish monarchs. The viceroyalties likewise demanded that the king respect for their identity and above all the defense of the territory. But the presence of the mestizo component was especially important in these festivities and decorations in the New World territories in order to communicate their own identity to the king. Let us recall that the cities sent the written testimony to the Crown to serve as a record of their loyalty and fulfillment of royal orders.

Source: Friar Cristóbal Cabellero, engraver, "Oath stage for Charles II of Spain in Lima," in José Mariano de Abarca, El Sol en León. Solemnes aplausos conque, el Rey Nuestro Señor D. Fernando VI. Sol de las Españas, Fue celebrado el dia 1 de Febrero del año de 1747. En que se proclamó su Magestad exaltada al Solio de dos Mundos por la muy noble y muy leal imperial ciudad de México, quien lo dedica a la Reyna N. Señora Dª Maria Barbara Xavier (Mexico: Imprenta Nuevo Rezado, 1748).

Image 4 Oath stage for Charles II of Spain in Lima

The Crown of Aragon

We shall now look at examples from the various kingdoms that formed part of the Crown of Aragon. It should be recalled that these were the regions that most openly supported Archduke Charles of Austria by force of arms in 1701 in his claim to Charles II's inheritance. That meant royal acclamations during the 18th century were an opportunity to show the features of the kingdoms' identity and past on the one hand and

their submission to the victor on the other. The city of Barcelona, As one of the places most severely punished for having supported the Austrian side during the War of the Spanish Succession, Barcelona had to demonstrate its loyalty to the new monarchy in a credible way. It therefore swore an oath to the monarch Ferdinand VI between 9 and 11 September 1746.28 The festivities were organized by the City Council and Guilds of the city. Tapestries were placed in all the streets along the route where the Royal Standard was to pass, which were sometimes decorated with poems, mottoes and other writings. There were also many portraits, embroidered cloths, gardens, mirrors, banners, altars and other types of decorations. In important parts of the city, such as the Plaza de la Ciudad and Calle Regomir, where the oath stages and triumphal arches were set up, portraits of the monarch with representations of his supposed virtues -Justice, Hope, Faith and Strength- were displayed.29

A platform set up in the Plaza del Palacio Real supported a statue of the king mounted on a prancing horse and portrayed as dominating two worlds, an impression reinforced by the words Utriusque Cesar that accompanied it.30 There was a canopy overhead and, as the written account specifies, the figure bore no arms and was bareheaded. The coats of arms of Catalonia and Barcelona were the main decoration for the static fireworks display in the same square, along with an image of Hercules, the city's legendary founder, sitting on a throne, together with Time, both holding a sun. Also in this square was The proclamation stage was located at the same place. It was square-shaped,with four bastions at the corners from which four pyramids emerged -two of them straight and two spiral-shaped. A figure bearing two coats of arms of Catalonia and two of Barcelona was placed at the top of each of these pyramids. The structure was decorated with more coats of arms of the principality and the city, as well as the figure of a nymph dressed like Hercules supported by a club between the ovals of these shields. The coats of arms of the different kingdoms of the Crown of Aragon (Valencia, Murcia, Majorca, Minorca, Ibiza, Athens, Neopatria, Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica and Naples) were also on display. The nymph offers its heart to the monarch, alluding to the fact that the provinces of the Crown of Aragon had surrendered to conquest by the king. 31

The figure of another nymph appeared beside this one, representing the city of Barcelona as a maritime deity supported by a trident like Neptune. It bore the standards of the nations defeated in naval battles: the Marseillans, Genoese, Pisans, Sicilians, Neapolitans, Moors, Greeks, Turks and Egyptians, and the words inscribed on it: Ipsa, et non alia, meaning "She alone, and none other, who achieved such long and absolute dominion on the sea," are revealing. The decoration was completed with the Royal Arms and, below it, that of Barcelona sustained by images of Immortality and Fame. The other three sides of the square were also decorated with a garden, an architectural view of three arches and the Colossus of Rhodes, as well as painted canvases of the maritime guilds.

The coins thrown to the public for the proclamation ceremony are also interesting. As was the tradition, the image of the appeared on the obverse side, while the reverse showed the god Mercury, "the planet that dominates Catalonia," with Cupid tightening the lace of a yoke linking the crowns of the kings of Castile and of Aragon as Counts of Barcelona, accompanied by the motto Amore revincit. In this way, a parallel was drawn between Ferdinand the Catholic and Ferdinand VI as two monarchs who had united the two kingdoms, thus ensuring a perpetual link between both territories and hearts for the Bourbons. All of this shows that Ferdinand VI's oath ceremony had become the perfect opportunity for the people of Barcelona to show their submission to the new dynasty and to assert the city's legendary foundation in ancient times by Hercules, its historic military tradition, and its greatness as part of the Crown of Aragon, as well as its commercial vocation.

Another territory that stood out for inserting elements of its identity into royal oath ceremonies by means of symbols was the Kingdom of Majorca in the 18th century. 32Perhaps because of the situation of change and crisis involved in the arrival of the Bourbons, royal festivals in that city remained as splendid as they had been during the 17th century,33 and the Majorcans maintained their loyalty to the Spanish monarchy in the form of the new dynasty, despite what had happened during the War of the Spanish Succession. The same type of event continued to be held in the same places where they had pledged loyalty to the Habsburg kings for centuries.34 Despite all the political and social changes taking place at the time, the artistry displayed on the oath stages involved powerful iconography reflecting the identity of the Majorcans, who were notable warriors. For example, there was recurring allusion to their warlike spirit, as well as to their commercial and maritime character, the fertility of their territory, and their promotion of the arts and sciences. Along these lines, the space adapted for the stage at Ferdinand VI's oath ceremony in 1747 was the Plaza de Cort, and the ephemeral construction was set up on mixed lines, sixty hand spans long, sixty-three high and six wide (Image 5).35

Source: Alberto Burguny, engraver, "Oath stage for Ferdinand VI in Palma," in Jaume Fabregues y Bauça, Tosco diseño del magestuoso aparato con que la Fidelissima Ciudad de Palma celebró el solemne Acto de levantar Pendones en nombre del Rey nuestro señor don Fernando VI de Castilla, y III de Aragon y Mallorca (Palma de Mallorca: Por la viudad de Guasp, 1747).

Image 5 Oath stage for Ferdinand VI in Palma

The oath stage was erected in front of the City Hall facade and reached the level of the building's Great Hall, both of which were linked by a corridor. It had various staircases of ten steps each, and a golden balustrade running all along the front. There were six pedestals on the balustrade, each of which supported a golden statue representing a mythological deity. The figures at both ends bore the coat of arms of the city of Palma, alluding to the history and idiosyncratic features of the Balearic people. The statue on the far right side depicted the sea goddess Tethys holding a trident and a sling and stabbing a dolphin with a flag. It showed the coat of arms of Carthage and the motto Funda falo, et solo vincit in allusion to the Balearic people's maritime victories against the Carthaginians. The one on the far left represented the Carthaginian general Hannibal, who was said to have been born on the island of La Cabrera, holding a flag showing a palm tree, a sword, and a book, along with the motto Ex utraque Palma, to symbolize the people of the Balearic Islands who had achieved fame through arms and letters.36

The middle statues on both sides bore the coat of arms of the Kingdom of Majorca. The one on the right represented Ceres offering the fruits of the islands to the monarchy, while the one on the left represented Hercules, the former lord of the islands, who destroyed giants with the Balearic sling-club. The more central figures on the balustrade were of Venus to the right, representing the beauty of the city and the Kingdom of Majorca, and Mars to the left, wearing Mercury's helmet and offering Balearic soldiers and sages to the monarch. The statues completing the upper frontispiece were of Immortality bearing the coats of arms of Castile, Aragon and Majorca to symbolize the union of the three crowns in a single head, and Fortune bearing the coats of arms of Castile and Aragon to recall the union of the two Crowns under the Catholic Monarchs in 1479.

The oath ceremony of Charles III, organized for 21 October 1759, also took place in Palma de Mallorca37 and the City Council put up a new stage in the Plaza de Cort for the occasion, with a design that was practically identical to the one erected for Ferdinand VI, although much more richly decorated (Image 6).38 This time, the first figure (from left to right) represented Minerva bearing a shield with the head of the Medusa the second was Bellona making a fierce gesture, and the third was Thetys with a trident and a sea snail, surrounded by several dolphins. On the right-hand side were the figures of three male deities: Neptune, Mars, and an Apollo crowned with laurel and bearing his quiver and lyre. All these figures symbolized the wisdom and valor of the Balearic people, their extraordinary skill with their slingshots, and their dominion over the seas. The two matrons depicted sitting on the cornice represented Fidelity and Constancy holding banners with the coat of arms of the kingdom and "giving to understand that the character of the Majorcans is of constant fidelity and faithful constancy to their legitimate Lord, King and Monarch."39 This representation of gods referring to wisdom, trade and war added to the idea of the good monarch ordering his subjects to observe his law and promising them rest, conveys a much more Christological message than that expressed for Ferdinand VI.

Source: Antonio Bordoy, engraver, "Oath stage for Charles III in Palma," in Relación de las festivas demonstraciones, y real aparato, con que la fidelissima, y noble ciudad de Palma, Capital del Reyno de Mallorca, celebró la real proclamación del rey N. señor Don Carlos Tercero (Palma de Mallorca: Joseph Guasp, s/a).

Image 6 Oath stage for Charles III in Palma

The position of the Kingdom of Valencia with respect to royal festivals was very similar to that of Majorca, although in this case the monarchs did visit the territory several times. We have accounts of royal visits to the realm used for the purpose of holding the Cortes of the kingdom, such as the visit by Philip III in 1604 and that of Philip IV and Balthasar Charles in 1645.40 In fact, due to circumstances directly related to the laws and liberties of the Kingdom of Valencia, no royal proclamations were made during the 17th century. The ceremonies consisted of the aforementioned oath by the king to uphold liberties, and the oath of obedience by the representatives of the kingdom on the occasion of the Cortes.

Everything changed in the 18th century when the Valencians showed their support for the Austrian candidate, proclaiming him their king in Valencia in 1706. Because of this, the visit of Philip V, Elisabeth Farnese and Prince Louis to the Valencian capital in 1719 was very significant. Given that said kingdom, like Majorca and Barcelona, had supported the Archduke of Austria in the War of the Spanish Succession, the monarch reduced reception events to a minimum, doing without a triumphal entry. He also demanded that Valencia should go to pay its respects at the Royal Palace, which, it should be recalled, lay outside the city walls. Along these lines, he eliminated any reference in the ephemeral decorations to the pact between kingdom and monarch or any assertions by the authorities of the kingdom or the city. According to Monteagudo, it should be recalled that Philip's Valencian supporters saw the armed conflict as a defense of what had been acquired: the preservation of their crown and scepter. During the 18th century, the supporters of Philip V thus justified his warlike character and image while simultaneously acclaiming him as virtuous, religious and holy, since they viewed the war as a religious struggle.41

From then on, the Castilian oath ceremony was imposed in the Kingdom of Valencia. The first of these ceremonies was for Louis I in 1724. The young monarch renewed Valencian fidelity to the Spanish monarchy, since he was a Spaniard. He also represented the hope for peace and concord, although the brevity of his reign would frustrate this desire, which was subsequently transferred to Ferdinand VI.42 The swearing in ceremony for Charles III in Valencia was perhaps one of the most outstanding in terms of asserting the idiosyncrasy of Valencia on the oath stage.43 In its coat of arms -the same one that appears on the back cover of the account-Valencia always showed its dual loyalty. In addition, the account of the festivities gives enormously exaggerated weight to the virtues of the Valencians: their good climate, their hard-working nature, and their loyalty to the Crown. The façade of the City Hall was profusely decorated with tapestries and damask curtains. The Royal Standard was hung on the balcony, sustained by the coat of arms of the city and supported by various globes with trophies. There was also an engraving representing the majestic decoration organized by Mr. Vicente Ramón. The account of the festivities includes a magnificent allegory of the kingdom surrounded by cornucopias, elements alluding to the promotion of the sciences and maritime trade.44

The oath stages set up in the Llano del Real and the Plaza del Mercado, where the second and third acts of proclamation took place, were simpler, although there was constant allusion to the abundance of the kingdom in the form of cornucopias. Even more interesting was the altar set up in the Plaza de la Seo opposite the stage on which the first act of proclamation took place. A huge canvas painted in perspective represented a magnificent architectural creation (Image 7). It was the creation of Carlos Francia, the famous painter of flowers and garden views who also made the engravings for the account of the festivities. The view included a niche in which a huge equestrian statue of Charles III was placed. The allegorical figure of Valencia portrayed as Minerva appears at his feet offering up instruments of mathematics and the arts on a tray. Her face is covered by a sun, and flowers, fruits and medals flow from a cornucopia at her feet. The inscription -Valencia Fortunata in omnibus felix- clearly alludes to the happiness and fortune of the realm: "How the sciences flourish and shine in Valencia and how much more they will flourish and shine encouraged by the rays and influences of the new Sun."45

Source: Carlos Francia, engraver, "Stage in the Plaza de la Seo for Charles III in Valencia," in Mauro Antonio Oller y Bono, Proclamación del Rey Ntro. Sor. Dn. Carlos III. (Que Dios guarde) en su fidelissima ciudad de Valencia, presentada al público en esta memoria (Valencia: Por la viudad de Joseph de Orga, 1749), Stamp 2.

Image 7 Oath stage for Charles III in the Plaza de la Seo in Valencia

A series of framed images placed in front of the platform showed a magnificent garden bordered by allegorical representations of the rivers of the kingdom (the Palancia, the Turia, the Júcar and the Mijares) fertilizing the Garden of Spain with their waters. Allegories of the cardinal virtues of Loyalty, Valor, Religion and Piety, the Royal Arms, the coat of arms of Valencia, and references to Saint James as the patron saint of Spain, along with trophies, cornucopias, and garlands completed the decoration. As was the custom in Valencia, the streets for the procession on the third day were full of altars and decorations depicting the patron saints of the churches, convents and guilds.

The oath ceremony of Charles IV took place in the city of Valencia in 1789. An enormous, beautiful picture of the static fireworks display for the occasion has been preserved (Image 8).46 The interesting thing about the watercolor painting is that, although the royal symbols appear in it (globes with the columns of Hercules and a crowned sun), the outstanding feature is a gigantic version of the city's coat of arms crowning the whole structure on the dome of the small pavilion in which the equestrian figure of the monarch is enshrined. This is known to be the work of the pyrotechnician and painter Domingo and Aguilar Mariano Babiloni, who also suggested that the structure should move. Of course, such a size, practically equal to that of the monarch, was no coincidence. The presence of the giant version of the city's coat of arms meant not only the submission of Valencia to its king, but also the awareness of a past historical relevance and the memory of its identity as a land, which had not been lost.

Conclusions

The examples dealt with in this study show that the ceremonies established at the end of the 16th century to acclaim the Hispanic monarchs at the royal court were transferred to the other capital cities of the kingdoms and viceroyalties of the composite Hispanic monarchy. Clearly, the same types of ephemeral architecture and decoration, as well as the propaganda symbols of the monarchy from the 17th century onwards and especially after the 18th century were transferred along with the ritual. But at the same time, we also find that the subjects in the different parts of the monarchy also wanted to insert their own identity into these decorations and show their own identity as kingdoms and cities. In the general decoration, as well as in the indispensable coats of arms, we also find many references to the historical and social idiosyncratic features and the political circumstances forming these particular identities.

Assertions regarding the excellence of these kingdoms and cities -their climate, their abundant production, their gifts for trade, and their cultural development- are clear. Together with this, reminders of their history, which forms the substrate for their identity, are always present. The demands they made on the monarch concerning the need to protect their borders from enemy attacks should also be highlighted. Along with this came the call to respect their rights and liberties, while never ceasing to declare their belonging to the composite monarchy and their submission to the monarch. But it is interesting to note that although during the 17th century the royal oath was only important in territories like Portugal where royal power had to be consolidated, there was a notable change in the prominence given to these ceremonies in the 18th century. This is demonstrated by the fact that the only documentary references that were preserved of 16th century and 17th century oath rituals contain are very few edited narrations of these festivities and still fewer illustrated ones, with the exception of those from Portugal. In contrast, an abundance of these accounts were published in all the different territories of the monarchy during the 18th century. It is also evident that more prominence was given to the entries of queens than to the proclamations of kings in Madrid during the 17th century. This situation would change in the 18th century, however, when the Bourbon dynasty, seeking to legitimize its monarchy, would prioritize the entrance of the king and its consequent proclamation in the capital, Madrid, as in all the other cities of the monarchy.47 Nevertheless, it was precisely in that same period that all cities, due to various circumstances such as post-war repression and nascent Creole pride, as we have explained above, would give more prominence to elements of their own identity and assert their claims for respect and protection, a fact that was reflected in the rich ephemeral decorations created for these ceremonies.