Introduction

In 1604, don Pablo Paxbolon, one of the most reliable indigenous allies of the Spanish in their attempts to take over land held by unconquered Mayas, accompanied an expedition into the interior of the modern-day state of Campeche. Though the expedition included an official interpreter, Cristóbal Interián, don Pablo’s prestige among Mayas made him a useful intermediary. He received testimony from the Mayas of Nacaukumil (Ququmil), who had fled colonial rule, and relayed their message of submission to the Spanish expedition. He also translated for the Spanish heads of the entrada (military expedition to subjugate an indigenous population), who accepted their surrender by organizing the town’s leading men into a Spanish-style cabildo, or town council.1

Nacaukumil’s likely location was near Paxbolon’s ancestral homeland of Acalan, where his Chontal ancestors had resided before their forced move to Tixchel, closer to the Gulf Coast where friars and encomenderos closely monitored them. While a few Chontals resisted relocation and remained behind, other Mayas had moved into the uncontrolled spaces. Nacaukumil’s inhabitants were likely a mix of unconverted Chontal Mayas (gentiles) and Yucatec speakers who had fled colonial rule. Only two individuals were named, Pedro Ek and Pedro Ceh. Judging by their Spanish baptismal first names and Yucatec surnames, their origins were in Yucatec Maya territory. Such migrations accompanied conquest and subsequent reducciones, or removals and concentrations, contributing to an overlooked mobility in the Maya world. Intermediaries like don Pablo, familiar with the people and the landscapes, became indispensable negotiators in unconquered Maya regions in the interior.

Like his conquest-era grandfather, don Pablo Paxbolon benefited from his allegiance to the Spanish as they attempted to pacify Mayas deeper in the interior. His grandfather, the Chontal Maya Paxbolonacha, sided with Cortés and played a key role in the 1525 execution of Cuauhtemoc, heir to the Aztec throne.2 For the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, at least, the strategic alliance with the Spanish paid off. Paxbolon ruled the Chontal from Tixchel with little interference. Much of this detailed dynastic history reaches us through the petitions of his Spanish son-in-law, don Francisco Maldonado and his mestizo grandson Martín Maldonado. The two cited Paxbolonacha’s and don Pablo’s deeds in support of their petition for an encomienda.3

In 1612, a second Pablo Paxbolon, an escribano (notary) of Tixchel, contributed to the efforts of Francisco and Martín Maldonado to assemble documents in support of their petition for an encomienda. He translated one of the first documents to appear in the Paxbolon-Maldonado Papers, a 1567 Nahuatl document (now missing) composed by Juan Bautista Celu, a previous escribano.4 Fluency and literacy in multiple Mesoamerican languages made indigenous translators essential interpreters. Significant numbers of conquistadors, their descendants, and other Spaniards, such as don Pablo’s son-in-law Francisco Maldonado (the second Pablo Paxbolon was not his son nor heir), learned one indigenous language, but those who spoke multiple native languages were rare. In multilingual settings, indigenous interpreters played a key role in mediating with unconquered and fugitive Mayas, whose flight persisted over the long durée of the colonial period.5

Decades later, in 1671, Pablo Paxbolon resurfaced a third time as the name taken by a Maya leader whose opposition to Spanish rule was exactly what Paxbolon and his cohort had attempted to snuff out.6 Due to the hardships of an exploitative repartimiento, a system of credit forcibly imposed on indigenous towns, many Yucatec Mayas fled into the interior of southwest of modern-day Campeche.7 A report by fray Francisco Treviño, comisario general of the New Spain’s Franciscans, noted that despite recent campaigns aimed at subjugating refugee and rebel Mayas, many independent settlements continued to resist forced relocation and congregation. During the seventeenth century, Maya leaders emerged, calling upon prophecies and hearkening back to past leaders in their assertions of regional authority. One leader of Chunpucte in the 1670s claimed the name don Pablo Paxbolon, after, in the words of the Franciscan friar, “a lord of these lands.”8

This final don Pablo Paxbolon could not have differed more from his namesake. He encouraged resistance to conquest instead of assisting in reducciones, promoted traditional Maya religious beliefs, and rejected the entreaties of the friars to allow the sacraments. He also did not assist in any translations. Instead, other translators worked with missionaries and armed Spaniards as they attempted to reassert control over defiant pueblos. However, his adoption of the name likely revealed his ability to lay claim to the legacy of the prominent past leader whose lands included Yucatec, Chontal, and Nahuatl speakers. If he was not literate, he at least had enough familiarity with regional Maya leaders of the past to deploy a widely recognized name with symbolic importance among diverse Maya groups to rally resistance to Spanish rule.9 Moreover, his Spanish first name and Maya surname indicates that he did not belong to an unconquered Maya group, but that he had likely fled from a subject area into the uncontrolled interior.

The three men known as Pablo Paxbolon spoke multiple indigenous languages. This made them ideal intermediaries between Spanish authorities and indigenous inhabitants at the borders of effective colonial rule, where linguistic diversity prevailed. Between the three, they spoke or wrote Yucatec Maya, Chontal Maya, Nahuatl, and Spanish, though the final to bear that illustrious name likely only spoke Yucatec and Chontal Maya. The first two were more typical of the early seventeenth-century translators outside of the political centers of Yucatan and residing closer to neighboring, partially conquered Maya lands. The blurring boundaries between different groups of Maya-in flux due to flight into the interior-made polyglot indigenous leaders adept mediators. The Maya interior was difficult terrain for Spanish-headed forces. In order to stem the tide of Mayas abandoning their towns, they relied on the mediation, cultural fluency, and linguistic abilities of indigenous interpreters. Brute force alone would not suffice.

Seventeenth-century intermediaries such as don Pablo Paxbolon and other go-betweens in the middle period in Latin America have rarely figured prominently in studies of translation and translators.10 Previous studies tended to focus on individual conquest-era and early colonial translators such as Malintzin or Gaspar Antonio Chi. The best-known translator of the contact period, Malintzin, figures prominently in many works on the subject.11 In the past two decades, studies of translation have moved away from key intermediaries of the conquest era to translation processes and the broader role of translators in institutional settings.12 One innovative approach has drawn attention to translations of content held in native modes of communication, such as the Andean knotted strings known as khipus and Nahuatl and Mixtec pictographic writing, and legal documents in Spanish tribunals.13 However, translation between unconquered and fugitive indigenous groups and the friars and neo-conquistadors who attempted to subjugate these resisters of colonialism have received little attention. This article examines the individuals who translated and their role in the Maya interior’s long conquest that paralleled the development of different personnel and duties on the part of the interpreters general, official translators of the province from the 1560s until 1821. These court interpreters, usually creoles who tended to be bilingual by the mid-seventeenth century, had skills suitable for a courtroom setting and legal translation, but they did not suffice for the demands imposed on multilingual translators whose services were needed in the polyglot context of the Maya borderlands.14 The imposition of European laws and associated tribunals on subjugated peoples made the post of interpreter general a stable position attractive to bilingual creoles, but the widespread flight from and evasion of colonial rule by thousands of Mayas during the seventeenth century forced Spanish neo-conquistadors to continue to rely on indigenous translators whose multilingual abilities, cultural fluency, knowledge of the terrain, and status as trusted brokers made them more suitable than Spanish-descent translators.

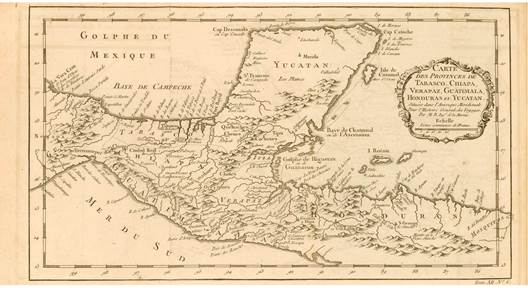

Source: Antoine François Prévost, Histoire générale des voyages, ou nouvelle collection de toutes les relations de voyages par mer et par terre, qui ont été publiées jusqu’à present dans les différentes langues de toutes les nations connues (Paris: Chez Didot, Libraire, Quai des Augustins, a la Bible d’or, 1744), vol. 12 (following p. 240). Courtesy of John Carter Brown Library.

Map 1 Central America including part of Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua

From Conquest to Colony: Changing Duties of Interpreters

The conquest of Yucatan (see Map 1) was never complete during the colonial period. The entradas subjugated individual ethnic groups one-by-one, making the conquest of the southern lowland Maya a piecemeal and protracted process. Frequent and persistent abandonment of pueblos under Spanish rule undermined the Spaniards’ effort. Colonial control brought new taxes, labor demands, violent repression of religious practices, forcible relocations, and the imposition of European norms. Not surprisingly, Mayas resisted the entradas, new taxes, and labor demands through flight to uncontrolled spaces. Encroachment by Spaniards led to migrations by Mayas.

Mediating colonial rule depended on adept intermediaries. Interpreters were indispensable in the efforts to bring all of the Maya population under Spanish rule. During this early period, conquistadors learned from captured Mayas, domestic partners (not all of them voluntary), to undertake rudimentary translation, or they relied on captive indigenous translators, lenguas forzadas,15 often youths chosen for their aptitude in rapid language acquisition. Nearly all expeditions included interpreters, though rarely did leaders credit them for their key role. Their nuances, tone, and precision in translation could contribute to success or doom an expedition to failure. Traveling without a translator contributed to the demise of the first of Francisco de Montejo’s three entradas (1527-1528, 1531-1535, and 1539-1542). The best and most motivated interpreters, such as Malintzin, brought cultural and geographic knowledge as well as fluency in multiple languages. The less helpful ones deserted, an unsurprising choice since they were coerced, captured, and rarely paid.

Conquest-era translation was oral. The mid-sixteenth century process of “reducing” Yucatec Maya to a European script led to new demands for interpreters.16 Interpreters needed to translate documents, including petitions for privileges or denunciations of abuses. The establishment of an Indian Court specific to Yucatan and distinct from the tribunal based in Mexico City led to the creation of an associated legal post, the interpreter general. As the court took shape from the 1560s to the 1590s, the interpreters’ ties to the court strengthened.17 By 1592, they acted primarily as legal aides. Their work consisted of legal translation: providing Maya elites with rulings and confirmations of privileges, translating Maya petitions and written complaints into Spanish, and translating oral testimony in courts and jails. For example, the interpreter general Diego de Burgos translated previously drafted Maya documents to resolve land disputes in the area around Maní.18 Oral testimony also required interpreters. In one of the earliest recorded instances, Gaspar Antonio Chi and Alonso de Arévalo translated the testimonies of suspects in an inquiry into accusations of idolatry in and around Maní (1562-1563).19 Sixteenth-century interpreters had traveled widely, translating interrogations in distant pueblos. Later, most legal translation performed by interpreters general took place in Mérida, the province’s capital. By contrast, interpreters who accompanied expeditions to convert or conquer resistant Mayas traveled widely, acted as guides, served as informants, and translated multiple languages.

Distant from Mérida, however, translation as mediation continued to be a necessity. The linguistic abilities and familiarity with indigenous culture made Mayas a regular part of efforts to persuade newly contacted and rebellious groups to accept or reenter colonial rule. They differed from the later seventeenth-century interpreters general in Yucatan who tended to be creoles, fluent and literate only in Yucatec Maya and Spanish.20 Furthermore, interpreters general rarely were willing to travel to translate, and interpreted in legal settings in or near Mérida. This left much of the translation work outside the boundaries of colonized Yucatan to indigenous intermediaries, recruited or coerced for specific expeditions.

The Maya Interior of the Seventeenth Century: Migration and Language Change

Despite claims of the completion of the conquest in 1542 (pushed back to 1547 by some scholars), Mayas in Yucatan’s interior-much of modern-day Tabasco, Petén, and Belize, as well as southern Yucatán, Campeche, and Quintana Roo-defied colonial control. Spanish entradas, diseases, flight, and English invasions altered the linguistic landscape as they shaped the Mayas of the interior. Entradas were followed by forced relocations, leaving behind voids as other Mayas-often speakers of different languages-moved into deserted spaces. Full-fledged, large towns in areas that had fully evaded conquest or successfully thrown off Spanish rule, such as the Selva Lacandona (in eastern Chiapas), the Lake Petén area, and Tipú in modern-day Belize, included Sak Bahlam, Nohpetén, and the town of Tipú itself.21 Between these permanent, sizeable settlements of a few thousand and the Spanish-controlled territory to the north, there were hamlets of dozens or a few hundred residents.22 On occasions, their numbers exceeded one thousand.23 Their permanence was challenged by the entradas aimed at capturing them and resettling them. As the colonial period progressed, such settlements decreased in size to a few families.24

Overall, Spanish invasions and subsequent entradas that reduced the territories held by independent Maya diminished linguistic diversity. Complicating matters further, in the seventeenth century, English interlopers raided, traded, and founded ephemeral settlements in the Laguna de Términos area and the coasts of modern Belize. Though their impact paled in comparison to Spanish wars, enslavement, diseases, and widespread forced relocation, English raids and slaving expeditions drove many coastal Maya groups into the interior as well.25 Disease decimated the populations, though the scale of the demographic decline in regions with a limited archival record is difficult to determine. Moreover, Spanish domination ended the circuits of commerce that created polyglot trading centers populated by speakers of various Maya languages and Nahuatl speakers, and the travel that connected Maya territories in Tabasco with entrepôts as far away as Honduras.26

Demographic decline, relocation to avoid conquest, and flight to avoid colonial impositions or slave raids by the English changed the linguistic map of the northern and central Maya lowlands from the early sixteenth century to the end of the seventeenth century. The most significant overall trend, the expansion of the Yucatec Maya territory, resulted from the flight of Mayas from Yucatan into spaces decimated by diseases or emptied due to forced relocations of the conquest-era inhabitants, often Ch’olan and Chontal speakers to the east and south. Chontal speakers also resided in parts of Yucatan until at least the late post-Classic and likely into the early colonial period around Mayapan and on Cozumel.27 Chontal in the Acalan region and Tixchel diminished so rapidly in part due to its similarity to Yucatec Maya.28 The second and less significant change saw the disappearance of Nahuatl (or Nahuat, a dialect of Nahuatl) as a minority language, present in Tabasco before the conquest and Yucatan after the conquest.29 In Tabasco, Nahuat speakers resided as far east as Xicalango before Cortés’s arrival.30 In sixteenth-century Yucatan, primarily Mérida, Nahua veterans of the conquest established the barrios of Santiago and San Cristóbal as neighborhoods for Central Mexican indios conquistadores.31 Their numbers were sufficient to require at least one interpreter fluent in Nahuatl in the second half of the sixteenth century, but by the early seventeenth century, Maya speakers dominated the cabildos of the two barrios. Nahuatl as language had disappeared or was only spoken in private settings.32 Nahuat diminished greatly within a century of contact in Tabasco, in part due to the precipitous demographic decline. The areas where Chontal Maya and Nahuatl overlapped shrank in part due to repeated congregaciones, or resettlements and concentrations of populations.33 Written Nahuatl seemingly disappeared entirely after the sixteenth century in Tabasco.34

The diversity of Maya languages also declined. Speakers of languages within the larger category of Yucatecan Maya expanded to the south and west. These languages-Itzá, Lacandon, Mopán, and Yucatec Maya-differed to a degree, though scholars still debate their mutual intelligibility. Within the Yucatecan Maya language family, individual languages differentiated further. During the seventeenth century, Itzá and Yucatec Maya were mutually intelligible according to all but one contemporary source.35 Lacandon evidently split from Yucatec Maya during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.36 Mopán, the most geographically and linguistically distant from Yucatec Maya, prevailed in eastern Petén and southern Belize.37 It separated from the other Yucatecan languages as early as one thousand years ago, but contact with Itzá speakers led to more similarities to that language than Lacandon and Yucatec Maya. In these areas, the Chol’ti’-speaking Lacandon and Manche Ch’ol persisted through the seventeenth century, which were not mutually intelligible with the Yucatecan languages.38

Mediators in Polyglot Terrain

The multilingual setting of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries favored indigenous and mestizo interpreters who tended to speak one indigenous language as their mother tongue and one or two more native languages over bilingual creoles and Spaniards who usually only spoke one indigenous language well. More mestizos and Mayas translated in official positions during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries than at the end of the seventeenth century and beyond. Creoles predominated in the post of interpreter general from the third decade of the seventeenth century onward due in part to its prestige and pay and also to an official preference for European-descent translators.39 As court officials, however, they were reluctant to travel far beyond Mérida. Outside colonial control, Spanish expeditions continued to rely on indigenous interpreters more than in established legal settings where colonial control had deeper roots. Two main reasons led to this situation. First, Maya translators fared better in diplomatic and linguistic terms with speakers of other Maya languages, including Chontal, Ch’ol, Mopán, and Itzá. Second, when indigenous allies were reluctant to travel into territories that presented armed resistance to Spanish entradas, the heads of expeditions coerced interpreters that they encountered en route.

In the early seventeenth century, at least two longstanding interpreters were not Spanish, Gaspar Antonio Chi, a Maya who had learned in the schools of Franciscans and served until his death shortly after 1610, and Alonso de Arévalo, a mestizo son of a conquistador.40 During the sixteenth century, several Mayas and mestizos served as interpreters regularly, likely due in part to their linguistic ability in multiple languages. Gaspar Antonio notably had a command of Yucatec Maya, Nahuatl, Latin, and Spanish.41 Mayas such as don Pablo Paxbolon and mestizos such as Alonso de Arévalo often spoke more than one indigenous language. Both Arévalo and Paxbolon spoke Yucatec Maya and Chontal Maya, and Paxbolon authored the single best-known Chontal document. Don Pablo may also have spoken if not written Nahuatl, a language rare in Yucatan, but common on the eastern borders of don Pablo Paxbolon’s province of Acalan.42 Paxbolon’s education in Campeche and his roots in Tixchel served him well in his conquests of the territory near Tixchel, which fell roughly on the border between Yucatec-speaking Mayas and Chontals. Indeed, his lifetime saw his territory and the Mayas under his rule increasingly pulled into the Yucatec Maya orbit, with growing numbers of Yucatec Mayas fleeing Spanish rule into the borderlands on the edge of Paxbolon’s Tixchel and Acalan.43

At the margins of colonial rule, mediation often benefited from the presence of respected indigenous elites or mestizos with prominent native ancestors. High-status Maya emissaries, recognized by both unconquered indigenous groups and Spanish invaders, were seen as trusted brokers by both parties. The original Paxbolon’s mediation demonstrated that his reputation as a leader-respected by both Spanish authorities and fugitive Mayas-was well established. Though possibly embellished, the probanza de méritos compiled by Paxbolon’s grandson, Martín Maldonado, plays up the deference shown to don Pablo even by refugees from Spanish rule.44 Respect for indigenous nobility likewise made Gaspar Antonio Chi an apt mediator. Despite his ill health and advanced age, in late October of 1609, Gaspar Antonio began to translate in a nearly six-month investigation and trials following the uprising in Tekax, apparently his last major undertaking as the province’s leading translator.45 In eras and areas in which colonial burden rested uneasily upon a restive indigenous majority, provincial officials relied more heavily upon intermediaries from the Maya elite.

Despite the reliance on indigenous and mestizo mediators such as Gaspar Antonio Chi, don Pablo Paxbolon, and Alonso de Arévalo during the early seventeenth century, the following decades saw increasing exclusion of mestizos from important posts. Even by the early seventeenth century, Chi and Arévalo were exceptional. An ambiguous classification in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, “mestizo” became a category of exclusion.46 Most mestizos failed in their attempts to retain appointments as official, salaried translators in the late sixteenth century. Creoles outmaneuvered Mayas to monopolize the post of interpreter general. In 1587, Marcos Rodríguez petitioned for the removal of unnamed mestizo interpreters (not named, but likely Antonio Nieto and Diego de Vargas) for their alleged abuses.47 Similarly, creoles managed to remove mestizos too from the post of interpreter general after Arévalo’s death in or around 1617. After Chi’s death in or shortly after 1611, no Mayas held the post. The scapegoating of Maya leaders due to their alleged complicity in revolts led to their disappearance from province-wide positions of authority. This policy of exclusion was implemented slowly, with Mayas and mestizos serving into the early seventeenth century, but evidently not in the second half of the century.

Only creoles held the position of interpreter general in Yucatan from the mid-seventeenth century onward. The linguistic diversity of Yucatan diminished as creole bilingualism in Yucatec Maya and Spanish grew. Knowledge of Yucatec Maya, and not Chontal or Nahuatl, sufficed. As the institution became more rooted, mobility decreased. As legal aides to Yucatan’s General Court of the Indians, the vast majority of their work took place in Mérida. Whereas earlier mestizo and Maya translators had taken on advocacy on behalf of Maya petitioners, the new generation of creole interpreters translated faithfully-most of the time-, but no longer provided legal advice to indigenous subjects.48 They seemed disinclined to travel, even less so to territories where unconquered Mayas still ruled themselves. In at least one instance, a creole interpreter general played a part in instigating flight and rebellion in southern Campeche. The following section explores how instead of tamping down inflamed sentiments, an interpreter general might exacerbate a situation.

The Flight of the 1660s: Disputed Causes

On May 17, 1668, Pedro García Ricalde, interpreter general of Yucatan, wrote to the governor from Tiop. Inexplicably present in a distant pueblo under tenuous colonial rule, he reported on the flight and rebellion around Sahcabchen. Most of the town’s population fled, though some members of the Maya cabildo stayed. Leaders of the resistance retaliated, stabbing the alcalde of Sahcabchen when he tried to prevent them from taking his wife as they retreated. The alcalde and his wife were among just 200 townspeople of approximately 700 who had not already fled voluntarily. Rebels pillaged the house of the Spaniard Antonio Gonzalez. García Ricalde reported that several Mayas from the vicinity of Campeche had also joined the movement, abandoning their towns to join the uprising. He blamed the turmoil on an unnamed pillaging enemy (probably English corsairs) or alleged that “the prophecies of their ancestors were now fulfilled,” spurring the flight of the indios montareses.49 García Ricalde failed to mention the root cause of the desertion of pueblos cited by Franciscans, encomenderos, and the Mayas themselves: the repartimiento imposed by the governor, don Rodrigo Flores de Aldana.50

A letter written a day earlier added more detail to García Ricalde’s missive. In his letter, fray Juan de Sosa noted that García Ricalde hid in Tiop’s convent out of fear of possible raiding parties. A single passage suggests the interpreter’s purpose. Fray Juan wrote that the interpreter had not attempted to collect anything in order to avoid upsetting the local population.51 This hinted at the translator’s reason for being there: He had probably traveled such a distance to collect debts in the repartimiento imposed on all indigenous adults in Yucatan. Unofficially, interpreters often served as agents of the governor, by recruiting or coercing labor and enforcing the collection of the repartimiento, two tasks facilitated by their bilingualism. Whereas authorities had once placed their faith in reliable intermediaries, interpreters general increasingly became the right-hand men of governors, creoles like García Ricalde.

Pedro García Ricalde had the confidence of don Rodrigo Flores de Aldana, but not the trust of most Mayas. The repartimiento de géneros sparked the rebellion and García Ricalde had used his fluency in Yucatec Maya and his familiarity with indigenous leaders to assist in its enforcement.52 Though clergymen and administrators blamed prophecies and marauding Mayas of la montaña for inciting the rebellion, leaders of the movement themselves cited the repartimiento, listing tribute exactions in detail as the cause of their flight. In 1668, Flores de Aldana directed the interpreter general to question voluntarily returned and captured fugitive Mayas about the causes of their flight. García Ricalde’s initial report to the governor implicated the repartimiento. Flores de Aldana rejected the findings. The interpreter yielded and publicly asserted that his intelligence showed that the Mayas were fleeing English depredations.53

Widespread abuses of power and egregious corruption under Flores de Aldana led to a wide-ranging residencia, a judicial review of an official’s service at the end of his term of office.54 Despite suspicions regarding his partiality toward the governor, García Ricalde continued to translate at least some of the accusations against Flores de Aldana lodged by the dozens of Mayas who took advantage of the residencia to make their long-ignored grievances heard.55 However, García Ricalde rarely translated alone. For example, when he interviewed Captain don Pedro Cima, the master carpenter of Mérida, who headed the guild of carpenters, masons, and blacksmiths working on the fortifications of the provincial capital in their demand for back pay for the thirteen months they had worked, García Ricalde translated their verbal testimony and Nicolás Cardenia translated their official petitions from Maya into Spanish. Though crown policy mandated the presence of two interpreters in all translations of indigenous testimony, the directive was rarely followed.56 It does appear to have been the prevailing practice when authorities feared intentional mistranslation. García Ricalde certainly proved his lack of trustworthiness, at least when it came to accurate, unbiased translation.

As the investigation progressed, the incoming governor and juez de residencia, don Frutos Delgado, found García Ricalde to be rather untrustworthy and distanced him from the proceedings. García Ricalde was hardly a neutral party. In another complaint included with the residencia, the blacksmith and Alférez Juan Pot of the barrio of Santiago complained that the governor had underpaid him for a repair to his carriage. This time the intermediary who relayed the governor’s refusal to pay was not García Ricalde.57 Pot’s complaint was translated by the two “named interpreters” who served in the residencia, Juan de Villanueva Infante and Diego Rodríguez. The procurador in the residencia, don Francisco de Rosado, evidently trusted these two translators more than the interpreter general, who was complicit in the chicanery of the governor.

García Ricalde’s presence in the far reaches of Yucatan’s territory during massive flight and insurgency did not defuse the situation. He evidently was present not to translate, but to impose the repartimiento, the cause of the uprising and flight. Faced with raids and attacks, he hid. Not surprisingly, later expeditions employed indigenous interpreters for their cultural fluency as well as their ability to communicate in multiple languages. As the seventeenth century entered its final decades, colonial authorities redoubled their efforts to conquer undefeated Mayas. As they did so, they relied heavily on indigenous translators.

Literacy and La Montaña

Translation involving fugitive communities in the later seventeenth century increasingly required written translation as more Mayas outside colonial rule wrote Yucatec Maya in the European alphabet.58 The need for literacy in both Maya and Spanish rather than fluency in multiple indigenous languages also led to the prevalence of creoles. Growing numbers of creoles spoke and wrote Maya as the seventeenth century progressed. Mayas, on the other hand, communicated primarily in writing. As a result, interactions with Mayas who had established independent communities in la montaña complicated the logistics of on-the-ground translation. Though Mayas who worked on behalf of the entradas often handled verbal communication, creoles usually translated written texts far from the action. By the seventeenth century, independent Maya polities rarely consisted solely of indigenous groups who had limited contact with Maya and no experience of colonial rule. Many Mayas who lived beyond the reach of Spanish authorities had resided in towns administered by clergymen and civil administrators. Significant numbers were from the literate elite of these pueblos. The interrogation of a captured spy from la montaña helps to illustrate this point.

Juan Aké, captured on suspicion of spying on Campeche to determine whether a military response was being prepared, demonstrates how literate members of society slipped away from their pueblos to join Mayas beyond colonial control. Under questioning, Aké revealed that he had served as the escribano and previously as maestro de capilla of Bolonchencauich. Eight years earlier, he fled to Tzuctok, the first pueblo beyond Spanish control. As an escribano and maestro de capilla, Aké was undoubtedly literate in Yucatec Maya written in European script.59 Upon his apprehension, Aké had in his possession a blank sheet of paper. He indicated that he intended to write a petition to the teniente del gobernador (roughly, lieutenant governor) in Campeche and return after six days to relay the response to teniente Alonso Pix, who led the fugitive Mayas.60 Aké admitted that his travels “servía de correo,” delivering correspondence as part of an informal postal service of messages between the many communities outside Spanish rule. Aké also signed his name at the conclusion of his questioning.61

Other evidence of literacy in uncolonized spaces emerges from the interrogations of Juan Aké and other indigenous officials questioned on suspicion of communication. Unprompted, Aké listed several other “caciques” he encountered while living in unconquered territory, including Francisco Ku, Juan Yam, and Diego Piste of Champoton. Their names-Spanish first names with Maya surnames-indicate that they were baptized and born under Spanish rule. Caciques were not always literate, but if they were, their writing would have been in the European alphabet rather than hieroglyphic writing by the second half of the seventeenth century.

On the Periphery: Indigenous Interpreters of the Late Seventeenth Century

Farther into the interior, fewer indigenous leaders wrote in Yucatec Maya, however. Cultural fluency mattered as much as an ability to speak multiple Maya languages. Yucatan’s governors appointed trusted creoles to manage official business for most of the seventeenth century, but few had the acumen for negotiating acceptance of colonial rule. This left much of the mediation in linguistically varied territories up to unofficial interpreters appointed or coerced into service. One such early example, Bernardino Ek, served as the translator for an ill-fated early expedition to conquer Petén Itzá between 1621 and 1624 under Captain Francisco de Mirones Lescano and the leading religious figure, fray Diego Delgado.62 The expedition ended badly for the Spanish and their Tipuan allies. The Itzá killed eighty Tipuan Maya and Delgado, who had split from Mirones’s party. Two Spanish soldiers sent by Mirones brought the Maya translator with them in 1623 to determine their fate. All were captured. Ek alone escaped. The Itzá retaliatory expedition caught Mirones unaware in Sacalum and killed the entire party. Ek’s survival allowed him to provide the only witness account of the demise of the entrada, relayed to the governor and recorded as history.63

Such entradas into completely unconquered territory were more common later in the century. The final decades of the seventeenth century ushered in a push to subjugate the remaining bastions of indigenous independence in Maya lands. Expeditions of conquest aimed at the Manche Chol, the Mopan Maya, southern Yucatec Maya speaking groups such as the Cehaches, and, finally, the last independent Maya group organized into a kingdom-the Itzá Maya-took place during the final decades of the seventeenth century. For these expeditions, heads of the entradas coerced or recruited indigenous interpreters and relied on their participation in campaigns that moved through varied linguistic terrains, echoing in many ways the conquest era of the first half of the sixteenth century. Despite a longstanding prohibition on slavery, one of the many exceptions granted to “discoverers” allowed taking (llevar) three or four Indians to serve as interpreters.64 Though interpreters general received a yearly salary of 200 pesos, often supplemented by prohibited but widespread bribes, interpreters of expeditions were either drafted by force or volunteered as a show of loyalty, similar to Ek or don Pablo Paxbolon earlier in the century.

A 1695 expedition to subjugate the Itzá kingdom, which ended in failure, relied on the services of indigenous interpreters who spoke multiple Maya languages. Others acted as emissaries, including the Tipuan Mattheo Uicab, who attempted to relay messages of peace and unidentified gifts in a failed effort to secure a peaceful surrender.65 One interpreter, “cacique” Yahcab, volunteered to serve as a translator, though one suspects that some degree of coercion may have been involved. A Mopán, Yahcab was chosen for his ability to communicate with both Itzá and Ch’ol Mayas. The friar who accompanied the expedition, fray Agustín Cano, had low regard for his abilities, which may indicate Yahcab’s reluctance to assist the Spanish rather than a lack of linguistic competence.66 In other instances, indigenous interpreters also brought a familiarity with the terrain and cultural knowledge to expeditions. In approximately 1695, a Maya interpreter only identified as “Fulano Vehin” not only translated but described the inhabitants and the size of the towns for fray Cristóbal de Prada.67

The 1690s brought about a multipronged approach to subjugate the most centralized polity remaining outside the Spanish orbit, the Itzá with their capital at Tayza in the deep interior of Petén, Guatemala.68 The expedition included at least one Spanish ecclesiastical translator, Br. Don Juan Pacheco (“Padre ynterprete”) and several indigenous interpreters, some who never appear by name.69 Nicolás Cardenia, one of two interpreters, participated minimally and only in matters that took place in those regions of Yucatan fully under Spanish control. He also translated a message from the governor, don Martín de Ursúa, ordering Maya pueblos of Oxcutzcab and Maní to provide armed men to serve on the expedition.70 He also interviewed a nephew of the Itzá ruler, Canek, when he visited Mérida as an emissary from the Itzá capital of Tayza.71 Apparently, he never left Mérida while the expedition took place.

Itzá Maya was mutually intelligible with Yucatec Maya, but the Maya emissaries’ ability to communicate in minority Maya languages that persisted in unconquered spaces led Spanish forces to include them on their expeditions. In 1696, during the final push into Itzá territory, the force under Captain Juan Díaz included two Mayas, one Itzá, known as Quixán, and an unnamed Chol.72 Not surprisingly, these captured indigenous interpreters (“heteronomous” in Michael Cronin’s definition) were not always willing emissaries on behalf of the Spanish.73 As Spanish forces closed in on Tayza, the unnamed Chol interpreter fled.74 Though interpreters general were trusted by governors, they were rarely disposed to undertake arduous travel. Indigenous translators, often coerced, had more cultural commonalities with unconquered Mayas and familiarity with unmapped lands, yet had little reason to act on the Spaniards’ behalf, especially when entering territories hostile to colonial oversight.

Conclusion

Despite an abundance of interpreters of indigenous ancestry in Yucatan during the sixteenth century, the permanence, pay, and prestige of the position motivated creoles to take over the post of interpreter general by the second and third decades of the seventeenth century. As creoles predominated, they became primarily court functionaries. Indigenous and mestizo translators, valued for their cultural fluency and multilingual abilities, were increasingly sidelined and called upon in more risky settings, such as entradas into the uncolonized interior. In a polyglot society, oral multilingualism served interpreters well. However, literacy and fluency in Yucatec Maya became increasingly common in the seventeenth century among creoles. In an era with reduced linguistic diversity, creole bilingualism, written and spoken, sufficed in most cases in which translation proved necessary.

Even after their exclusion from holding the post of interpreter general, indigenous translators were called upon or forced into service in armed expeditions against the many Maya groups still defying colonial rule. The long conquest of Yucatan’s interior lasted much longer than colonial accounts portrayed. Moreover, many Mayas joined unconquered counterparts after fleeing the constraints of Spanish rule. Some Mayas, such as the Xocmoes, relocated repeatedly to avoid subjugation.75 Some polities, such as the Itzá Maya, beat back attempts to conquer them until 1697. Others, such as Tipu or the Manché Chol, had nominally been conquered, but rather easily threw off the yoke of colonialism in the seventeenth century. Also, increasingly common were the settlements constituted by Mayas who fled colonial rule to set up towns in territory that bordered Yucatan, often dismissively demarcated as “despoblado” (unpopulated) on Spanish-produced maps. When Spaniards moved against the populations that did indeed inhabit these lands, they once again relied on the mediation and translation of indigenous interpreters throughout the seventeenth century.