Introduction

In 1907, Francisco Hechenleitner arrived at the home of Ceferino Currieco to remove him from his land in Coihueco Island (Map 1). Coihueco Island is a popular name for a marshy area bounded by the homonymous river and the Rahue River in southern Chile. Surrounded by water, it gives the sense of an island.1 Currieco’s family had been residing in Coihueco Island for at least fifty years. In November 1907, Ceferino, who lived with his son and his family, was building a new house, when Hechenleitner arrived to announce that their lands now belonged to the Rupanco Colonizing, Farming, and Cattle Breeding Company (Sociedad Colonizadora Agrícola y Ganadera Rupanco).2 Nine men armed with revolvers, shotguns, axes, and whips accompanied Hechenleitner, the local manager for the Company, to make sure the Curriecos complied. Ceferino did not surrender without a fight, and in the struggle, he was fatally shot.3

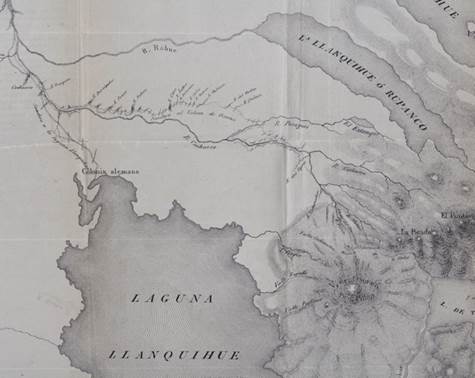

Source: Base map generated by the author with qgis

Map 1. Map showing the main sites referenced in this article

The assault on the Curriecos was not an isolated incident. Hundreds of people complained to Chilean authorities about the Rupanco Company’s constant harassment and violation of their properties. Violence against Indigenous peoples in the Americas has underpinned the creation and expansion of private property since the first encounters between Europeans and natives. During the nineteenth century, emerging Latin American states depended on the regulation of landed property to collect revenue, claim public lands, and build a bureaucracy. Simultaneously, the delineation of property sought to incorporate what authorities considered idle lands to a national territory seen as sovereign and to growing export-oriented national economies. Consequently, these regulations also forced Indigenous peoples to engage with a contractual state and abandon non-Western forms of understanding and using geographical space.4

This article foregrounds how racialized ideas of space that shaped the creation of private and public property fueled attacks on Indigenous and non-Indigenous peasants in southern Chile. The Chilean government, as other new states in the Americas, reproduced the recurrent colonial trope of Indigenous lands as empty territories.5 In doing so, authorities symbolically displaced native communities onto what Anne McClintock called “anachronistic space.” This trope situated Indigenous peoples “in a permanently anterior time within the geographic space.”6 For political elites, Mapuche and other Indigenous peoples of southern Chile lived in a “savage state” and the spaces they inhabited were construed as “empty geographies with enormous yet dormant economic potential.”7 Not surprisingly, since before independence, authorities in Santiago referred to the Mapuche heartland as “la frontera” (the frontier) evoking a liminal space they did not control. Chilean authorities used colonial representations of the south, broadly understood, as a site with no civilization, history, or rule of law to justify land distribution among “hard-working settlers” to transform barren land into “prosperous and blooming” holdings.8 Simply put, representations of space drove spatial violence to legitimize cultural hierarchies in southern Chile.9

The Chilean determination to invade and privatize Indigenous land in the name of the nation typified a common trend across the region. Indeed, Latin American ruling elites of the second half of the nineteenth century resorted to a myriad of nationalizing policies to consolidate the territorial expansion of the state, including national legislation on landed property, military campaigns against Indigenous peoples, and colonization at the hands of individuals or companies. For instance, the Brazilian Land Law of 1850 “forbade the acquisition of public land through any means but purchase,” while the Lerdo Law of 1856 in Mexico sought to privatize communal lands and “mobilize them in a commercial economy.”10 Farther south, Argentine authorities accompanied expropriation laws with a military campaign against nomadic and semi-nomadic communities in Patagonia and Chaco.11 From the coffee plantations in western Guatemala through the ranching estates in southern Brazil to the sugar mills in northern Argentina, the steady privatization of lands, especially at the hands of few companies, cornered peasants to sell their lands and join the workforce.12 Similar strategies in southern Chile illustrate how ideas about geographical space garnered collective aggressions against entire communities.

In addition to surveying spatial violence generated by the regulation of landed property, this article examines how local residents in Coihueco Island resisted removal through litigation, protest, and propaganda. As in other parts of the Americas, the homogenizing force of state policies crashed with historical realities on the ground, spurring multiple forms of resistance. In some parts of Mexico, for instance, native communities created farming societies (sociedades agrícolas) to counteract the liberal legislation of 1856, while others simply did not appear to register their properties or claim ownership of lots in communal lands, delaying the process.13 As Laura Gotkowitz argued for Bolivia, the liberal reforms that sought to eliminate Indigenous corporate lands inadvertently created legal mechanisms for communities to litigate privatizations and underpinned the emergence of Indigenous leaders to spearhead these movements.14 Something similar happened in Coihueco Island. The legislation regulating landed property in the late 1860s opened pathways for resistance in the courts, before police officers, through protests, and in local newspapers. These resistance methods join a constellation of efforts from Latin American Indigenous and non-Indigenous peasants to defy the political and economic elites’ attempts to erase them.

The creation of private property in southern Chile served a twofold purpose. First, it sought to delineate taxable property and public lands to gather revenue. Codifying regulation allowed national authorities to impose a legible simplification of the Chilean space while representing the state’s capacity to survey, manage, and collect revenue.15 Additionally, the creation of private property in southern Chile sought to settle (radicar) the Mapuche communities to permanent sites. As Raymond B. Craib put it, political elites in new Latin American countries searched for “fixed essences” critical to defining the nation-state. The delineation of private property and the bounding of specific people to particular terrains epitomize this “obsession with permanence” represented by an ability to measure, quantify, and regulate.16 In the Patagonian Andes, trading companies obtained land concessions to exploit natural resources beginning in the 1870s in Argentina and the 1890s in Chile. These concessions overlapped with previous land leases to individuals and Indigenous communities, while they also conflicted with trans-Andean passes that cattle herders had used for decades. Land concessions of large estates to companies worked as proxies for state action. These companies often committed to build roads, bridges, and harbors that would insert products into the market. Additionally, they often agreed to bring settlers, usually of foreign origin. The legislation issued in Chile to privatize lands provided a framework for colonization, land access, and business in the Patagonian Andes that legitimized spatial violence against earlier inhabitants.

Historians have long examined how private companies participated in the colonization efforts on both sides of the Andes. Some scholarship highlighted the pioneering enterprise of settlers as a nation-building mission in the corners of national territories.17 Others have examined how regional capitalist economies articulated land access and land tenure.18 Recent scholarship has shifted to a more critical analysis of the role of individuals and companies in the displacement of others. Alberto Harambour has examined how large colonizing companies in southern Patagonia transformed space through the concentration of property in the hands of a few people. Everyday exercise of power, he argued, rested on dispossession as a crucial aspect of state-building.19 Focusing on state violence in Araucanía, Jorge Iván Vergara and Héctor Mellado concluded that settlers often harassed and assaulted those who did not enjoy state protection, such as Indigenous peoples and poor Chileans.20 In Llanquihue, scholars like Paz Neira, Josefa Reyes, Samuel Linker, and Rodrigo Cánovas have done crucial work recording collective memories of acts of aggression, dispossession, and outright violence.21

Building on these perspectives, I explore understandings of the geographical space as a crucial element for the constitution of and resistance to violence in southern Chile. By analyzing legislation, its consequences, and responses to it, this article sheds lights on violence and resistance in the context of the colonization of marginal territories of Patagonia. Situated within a genealogy of violence in southern Chile, these strategies amounted to what Steve Stern has called “resistant adaptation,” seemingly unnoticeable efforts to “resist, evade, cope with, or deny their subjugation.”22 Specifically, the struggle in Coihueco Island exemplifies methods by which local residents resisted the presence of the company by, somewhat ironically, appealing to the state.

Organized in four sections, this article provides an account of how the creation of public lands through the establishment of private property targeted Indigenous territories. First, I frame the subsequent violence in Coihueco Island within a legislation that portrayed the territories in southern Chile as vacant. In the second section, I trace the consequences of these laws in the distribution of lands in Llanquihue Province.23 Two of these were the creation of vast land leases and the condition to bring European settlers to those dominions. Undoubtedly undermining Indigenous presence in specific territories, these leases resulted in a historical trajectory of violence in Coihueco Island, which I examine in the third section. The final section provides examples of methods of resistance to violence encountered by residents in the hands of employees of the Rupanco Company and its allies.

The Creation of Private and Public Property in Southern Chile

The Mapuche-Huilliche-communities specific to the Llanquihue and Valdivia districts-had been living in Coihueco Island since at least the late eighteenth century.24 After independence, Chilean national authorities recognized the juridical equality of Indigenous people while deploying evangelizing and diplomatic missions (parlamentos) to integrate Indigenous Mapuche communities into the new republic.25 At mid-century, this policy changed abruptly, replacing the initial protection of the Church with the creation of three new provinces in southern Chile: Arauco (1852), Llanquihue (1861), and Magallanes (1853). Hence, state bureaucracy would now dictate the organization of the territory, subduing Indigenous populations to a national sovereignty.26

Chilean authorities sought to protect state taxation interests through legislation.27 In 1866, one of the most consequential pieces of legislation on landed property allowed the foundation of towns in “Indigenous territory,” outlined the auction of public lands, forbade transactions between Indigenous and non-Indigenous individuals unless they held land titles, and established the Indigenous Settlement Commission (Comisión Radicadora de Indígenas). The commission had concentrated its efforts in Arauco since 1883 and moved on to Valdivia in 1907. Twenty years later, the group considered its work done.28 As José Bengoa argued, this legislation reflected a statist approach to land leasing, reducing Mapuche communities to smaller territories and forcing them to register their lands. Failing to prove ownership enabled the state to create the notion of vacant land (terrenos baldíos) as public property.29 As a result, in the eyes of the law, if anyone was living in a vacant lot, they did not have the right to sell it. This approach to the creation of public property through the delineation of private lots contrasted with the colonizing strategy in the United States, Canada, or Argentina, where immigrants could buy land directly from Indigenous people. Additionally, the law of 1866 came in the middle of a military campaign in Araucanía, the heartland of Mapuche territory. Authorities coupled legislation and military action to exclude Indigenous peoples from the Chilean republican project.30 Anchored in a discourse that vilified Indigenous peoples, the occupation of Mapuche territory would unify the Chilean geographical space while incorporating fertile lands to the capitalist economy.31 By creating a legislation that regulated land tenure and taxation, the Chilean government forced the Mapuche to apply for titles to their own lands.

Despite efforts to make space legible through the delineation of property, legislation was often confusing. For example, the law of 1866 required that all property in Indigenous territories have a corresponding land title. Hence, people with no title would have to register their property. For this, a surveyor would need to demarcate an applicant’s lot after taking notes of witnesses attesting to a person’s long-standing residence.32 Authorities assumed that ‘Indigenous territory’ typically referred to Araucanía. When the government created the province of Arauco in 1852, it included “Indigenous territory south of Bío-Bío River and north of the province of Valdivia.”33 However, the exact location of ‘Indigenous territories’ remained undefined in the law of 1866, prompting several interpretations. In 1873, the Supreme Court ruled that Valdivia was “under ordinary rules” and, therefore, not Indigenous territory because Indigenous people living there were “now civilized, they [did not] belong to untamed tribes.”34 A decade later, the national government forbade transactions between Indigenous people and other settlers until 1903.35 This meant that Indigenous people south of Araucanía, in Valdivia, Llanquihue, and Magallanes, had less legal protections against removals. In documents, Chilean authorities worried that land speculators would take advantage of natives to trick them into selling their lands at a low price. Hence, public employees shared the paternalistic mission of the state towards Indigenous people. In truth, state officials resented that the government was missing out on an opportunity to collect taxes as people settled on empty lots or bought lands from the Mapuche.36

In Llanquihue and Valdivia, the Chilean government favored the settlement of foreign families (colonos extranjeros), while in Arauco more lands were available to non-Indigenous Chileans (colonos nacionales).37 To attract farmers, the government reserved fertile acreage for newcomers at a low price and pushed Mapuche communities to smaller lots or reservations typically far from where they had lived for generations. Land prices about sixteen times lower than the national average lured settlers of European origin to Valdivia and Llanquihue. Many accumulated and sold lands triggering a spike in prices and prolonging speculation.38 The sudden rise in land prices during the 1870s and 1880s caused many Chileans to occupy lands illegally, exaggerate their boundaries, and deceive Indigenous communities into selling their lands. These actions eventually handicapped state leadership in the colonization of Valdivia and Llanquihue, as officers had to focus first on petitions, complaints, and trials before proceeding with land granting. The rising number of rural properties generated illegal occupation and displacements. Some of these settlers would eventually gain land titles, but some would not and would find themselves forcibly removed from the lands they had labored for decades. While foreigners received lands, Indigenous peoples in southern Chile were displaced, policed, and disciplined.39 Not surprisingly, these residents protested land grants in Coihueco Island.

The Distribution of Vacant Lands

As the Chilean government finalized its border negotiations with Argentina at the turn of the twentieth century, it granted vast extensions of lands to individuals to accelerate the colonization of the Andean valleys of the south. For instance, Juan Tornero received in 1901 “land in perpetuity” to bring “a thousand families of foreign settlers” in Magallanes Province. Three years later, the government extended this lease to lands in the province of Llanquihue and the rest between parallels 42º and 52º.40 Land grants to individuals amounted to a total of 4.7 million hectares in southern Chile, including Magallanes. Many of these vast land concessions to individuals became seedlings of land holding companies. Juan Contardi, former secretary of Magallanes Province, received in 1903 a lease of “the environs of Baker, Chacabuco, [and] Salto Rivers, and Lake Cochrane” in present-day Aysén Region.41 He then sold this lease to Tornero, who founded the Baker River Company (Compañía Esplotadora del Baker).42 Teodoro Freudenburg received a lease in the Bravo River valley, which he then transferred to the Bravo River Company (Sociedad Esplotadora de Río Bravo).43 Part of Tornero’s lands in Llanquihue eventually comprised the Chile-Argentina Trading and Cattle-breeding Company (Compañía Comercial y Ganadera Chile-Argentina), researched extensively by historians Laura Méndez and Jorge E. Muñoz Sougarret.44 At 40,000 hectares, the concession to Amadeo Heiremans was one of the largest, especially in the context of Llanquihue Province where the state had less available lands. The size of this lease was almost equivalent to all the Mapuche-Huilliche lands on the Pacific coastline of Llanquihue, and larger than all concessions granted to foreigners up to that point.45 Like most of other extensive leases to individuals, the Heiremans concession stretched to the Cordillera and included the Chilean side of a trans-Andean pass.

What all these concessions had in common was that they worked on the assumption that the leased territories were vacant. This is why extensive land concessions included a clause stating the responsibility to bring settlers (radicar colonos), regardless of who was living there. Chilean preference for foreign settlers was no secret. The government had been actively recruiting immigrants abroad since at least 1853, when it created the colony of Llanquihue (which became a province in 1861).46 In the vast land leases to individuals such as Tornero, Contardi, or Heiremans, settlers needed to comply with “age, nationality, and morality requirements,” which usually meant they had to be young enough to have a family, old enough to work in the fields, and European, “preferably […] Scandinavian, Dutch, Swiss; French, especially Basque; German, especially from the north; English, and Scots.”47 Almost immediately after receiving the land concession, Heiremans leased it to the Rupanco Company, of which he was a shareholder.48 Under this lease, the company was responsible for “bringing settlers and cover the cost of surveying the terrains.”49 However, companies like Rupanco engaged in speculative trading of shares instead of leading colonization efforts.50

The Rupanco concession, like other leases, rested on a genealogy of land grants that assumed that Coihueco Island was empty. In 1895, the government auctioned some of the lots in the environs of Lake Rupanco. A group of residents, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous, protested this trespassing, prompting a visit of the governor’s secretary, Rafael B. Pizarro.51 Born and raised in La Serena and educated in Santiago, Pizarro was an outsider to Llanquihue. Armed with new legal requirements to prove residency, he admitted that all nine protesters in Cancura (half of them women) could demonstrate that they had been there for at least ten years because of the works they evidenced in the lots: “They have cleared a part of [their lots] and some of them had plantations.”52 Everyone else, he argued, had multiple notifications to either leave or appear before a judge. Those with verifiable land titles did so. The protests made it to the desk of then Minister of Foreign Affairs, Luis Barros Borgoño, under whose purview fell the Office of Colonization that distributed lands in southern Chile. Barros Borgoño, a future shareholder of the Rupanco Company, resolved to displace farmers and compensate those “truly affected” with some lands near the town of Cancura.53

The Genealogy of Violence in Coihueco Island

The history of Coihueco Island reveals how authorities of Llanquihue identified the plains as an Indigenous space. One of the earliest, non-local references we have of Coihueco Island is two annotations naturalist Francisco Fonck made in his re-print of Fray Francisco Menéndez’s travels. In the 1790s, more than a century before the land concession to the Rupanco Company in Coihueco Island, Menéndez led four expeditions in search of a pass from Lake Llanquihue, in Chile, to Lake Nahuel Huapi, in Argentina, aided by Indigenous rangers. Fonck commented that the most acclaimed of these rangers was Juan Currieco, also known as Pichi Juan (Little John), because he began to guide new settlers as a child. He had accompanied the founder of Puerto Montt, Vicente Pérez Rosales, in his explorations of Lakes Llanquihue and Nahuel Huapi. Currieco also served other explorers such as Fernando Hess and Fonck himself. Fonck reported writing to the Chilean authorities against Currieco’s removal in Coihueco: “I wrote two petitions to the Government for his claims in Coihueco Island with no results.”54 Decades later, Juan’s son, Ceferino, will die when the manager of the Rupanco Company tried to remove him from that same land. Legends that followed immortalized Juan Currieco, and Coihueco Island soon became a reference for an Indigenous site.55

Portraying Indigenous territory as vacant also enabled the violence of erasing shared toponymy. Coihueco Island sits between Lake Rupanco to the north and Lake Llanquihue to the south. Testimonies collected by Neira, Reyes, and Linker report that Lake Rupanco had a different name, Llauquihue. One letter differentiates this name from Llanquihue, rendering a completely different meaning. While ‘Llanquihue’ means ‘sunken or hidden place’, ‘Llauquihue’ means ‘place of llauquis,’ where llauqui or puye (Galaxias maculatus) is a small freshwater fish.56 For newcomers, the names were confusing. In 1852, German surveyor Guillermo Döll produced a sketch of the lakes and cordillera synthesizing his findings (Map 2). Judging by its title, “Indicaciones para perfeccionar el Mapa de la Provincia de Valdivia, según los recuerdos de un reciente viaje al volcán de Osorno,” more than a summary, Döll viewed this map as a steppingstone towards a better understanding of the geographical space in southern Chile. The way he saw it, the toponym of the lakes was very confusing. In this sketch, Döll labeled Lake Rupanco as “Llanquihue or Rupanco,” displacing what he thought was the original name (‘Llanquihue’ instead of ‘Llauquihue’) with a different one, Rupanco. It might look like he misspelled ‘Llauquihue’ as ‘Llanquihue,’ resulting in two lakes with the same name. Years later, Döll highlighted this confusing toponymy to the Ministry of Interior and stressed his solution: “To avoid confusion between these names, I proposed long ago, in 1852, the name of Rupanco for the [one on the north].”57 While changing one name might have looked innocent, it rested on the assumption that it could be done. With that, Döll epitomized one aspect of the colonizing effort in southern Chile. As a foreign-born explorer, he exercised more authority on the production and reproduction of geographical knowledge than residents who had been living on the shores of the lakes for a longer time.

Source: Guillermo Döll, “Indicaciones para perfeccionar el Mapa de la Provincia de Valdivia, según los recuerdos de un reciente viaje al volcán de Osorno.” March 28, 1852, Biblioteca Nacional Digital de Chile (bndc), http://www.bibliotecanacionaldigital.gob.cl/visor/BND:156929

Map 2. Map of Lakes Llanquihue and Rupanco (1852)

In 1887, the national state granted land titles to some Mapuche-Huilliche families who had resided in Coihueco for generations, including the Raileos, the Guaiquimillas, and the Curriecos.58 Years later, in 1894, the government announced that surveys had been concluded and it was ready to sell lands in Cancura. People that were already living there requested appropriate compensation for removal from their lands. Based on the names of signatories, some of these lands stretched to Coihueco Island. They argued that not only had they lost their source of subsistence, but they also failed in their application for land leases elsewhere. Many had been in their lands for more than forty years, attested by the labor they put into their fields. For these 220 signatories, of which more than half were illiterate and needed someone else to sign for them, dispossession meant to be doomed to “serve as sharecroppers (not to say slaves)” of “foreign hands” that accumulated the region’s wealth.59 The new senator for Llanquihue, Ramón Rozas, dismissed the appeal arguing that the signatories either “ignored the day of the auction in the city of Valdivia” or “lacked the resources to undertake the trip.”60 The state official blamed his 220 constituents for their own luck: “It is easy to understand, Mr. Minister, the sad and dangerous spectacle of these people living in a surprise, without any resources, wandering in the dark and full of the desperation that hunger produces.”61

In the late nineteenth century, as companies advanced over southern Chile, the fertile lands of Coihueco increased their value. Cattle breeding developed into a more profitable activity; thus, the south received more investments from Santiago and Valparaíso. The settlement of Cancura, Coihueco’s urban area, sat on a busy route connecting the factories of Osorno with Puerto Octay, a harbor in Lake Llanquihue, and from there with the rest of the region. Coihueco Island ran from Cancura to the east, tapping on the western slopes of Puntiagudo Volcano and a valley that led to Lake Todos Los Santos, at the mouth of a trans-Andean pass into the Argentine plains. Hence, both location and soil quality raised the value of the land.

In 1896, the Chilean government celebrated a contract with Charles Colson, a French businessperson, to bring five thousand families over eight years to Coihueco Island. Authorities viewed this enterprise as a prompt solution to the desolate, unproductive fields of southern Chile.62 President Jorge Montt personally supported the contract. Colson, who enjoyed connections “with multiple colonization and transportation companies,” would bring to the country “reliable factors of progress, such as a gradual immigration of well-chosen people based on their nationalities, their habits of life and their work skills.”63 Particularly, Chilean authorities believed that settlers from a hierarchy of countries would undoubtedly boost economic production in the south. They favored immigrants from northern Europe, the British Islands, and some mountainous areas, like Switzerland and Basque country.64 These immigrants would settle in specific pockets of fertile lands, such as east of Villarrica, along the Maullín River, and in Coihueco Island. The entirety of Coihueco Island, claimed the president, had been lotted (hijuelizada), inferring that land leases were in the pipeline.65 Colson received a concession of 650,000 hectares distributed in Cautín, Valdivia, Llanquihue, and Chiloé to settle families that met “age, morality, labor, and nationality requirements.”66 With similar language, Amadeo Heiremans received a lease in Coihueco Island in 1904. As we shall see in the next section, the creation of large land grants triggered protests. However, there is no evidence that until 1904 Colson changed any aspect of Coihueco Island.

Resisting Removals in Coihueco Island

Though sparsely populated, Coihueco Island was far from uninhabited. Per the census of 1907, a community of 1,477 people resided in Coihueco.67 For comparison, the town of Puerto Octay had 628 people, while the urban area and its environs amounted to 1,325 inhabitants. Similarly, the amount of people residing in Coihueco Island compared to the population of any small town in Llanquihue, such as Pichil (a town north of Cancura, with 1,409 people) and Calbuco (a town at the entrance of Reloncaví Sound, with 1,395 people).68 The land concession to Heiremans and the Rupanco Company in Coihueco Island stipulated that they were “obliged to respect Indigenous settlements that might come in his land lease and the rights of settled residents.”69 However, the events in Coihueco Island epitomized the violent response from local authorities to the presence of Indigenous and non-Indigenous settlers in lands they deemed desirable for immigrants.

Indigenous communities started to protest in the local courts as soon as the Rupanco Company received the land concession. They presented themselves as Indigenous Chileans (indios chilenos), evoking their historical right to the land and their right as citizens of Chile. In 1908, cacique José Esteban Canuipan filed a petition for lands his father had received fifty-three years earlier. The estate was located on the 1855 version of the border with Argentina: “the mountain range where the streams part eastwards and westwards, that is, the divortium aquarum [dividing watershed].”70 Canuipan argued that those lands belonged to his community “by nature” (por la naturaleza misma) and it was up to the Executive to give them what was theirs. By identifying themselves as “the sons of this beloved but wretched Chile,”71 they simultaneously asserted their identity as people of the land (Mapuche) and acknowledged the important role the state played in verifying that identity. Canuipan wondered, “Are not we Chileans and, as such, [entitled to] shelter under the Patriotic Laws dictated by the wise for halting any threats from the ambitious [men] and the citizens?”72 In other words: the land gave Canuipan and his community their identity as Mapuche(-Huilliche), which was both challenged and reinforced by state laws. It was because they were Indians and Chileans that they could continue to claim those lands on the border.73

In December 1910, the Chilean Congress appointed a special commission to survey southern Chile to investigate numerous complaints received from “national settlers and Indigenous people.” At heart, the committee sought to reconcile current legislation with the reality on the ground and propose solutions where there was dissonance. To that end, the Parliamentary Commission held numerous townhalls across the southern provinces. During the month of February in 1911, they convened at La Unión, Osorno, Puerto Montt, Puerto Varas, and Puerto Octay, near Coihueco Island.74 The meeting at Puerto Octay received the largest number (138) of total applications to address land disputes, where about half of them (75) requested protection against the Ñuble-Rupanco Company.75

Some authorities were complicit in the forcible removal of people from their lands in Coihueco Island. In 1908, Federico Hechenleitner, brother to the manager of the Ñuble-Rupanco Company, used his acquaintances in police forces to remove Francisco Huaiquipan, Manuel Díaz, and José Antonio Cumacure. The three farmers complained to a judge that they had “buildings, tenants, crops, animal husbandry, and other works that give them rights” over the lands they have inhabited for more than twenty years.76 We know how the case got resolved. While protesters might have a reasonable defense, local authorities often permitted violent removals.

In light of the concession to the Ñuble-Rupanco Company, a judge ordered the removal of those who lived in Coihueco Island and had no effective land title valid for the government. On March 19, 1911, a violent crew attacked Candelaria and Genaro Saldivia at their home and forced them out of their 10-hectare land. The assault began with an innocent knock on the door. The sixty-year-old woman answered only to find judge José Núñez, who was also an employee of the Ñuble-Rupanco Company, reading a decree of dispossession against their son-in-law, Adolfo Mardorf. Mardorf, one of the 75 petitioners of protection against the Ñuble-Rupanco Company in the townhall with the Parliamentary Commission, held the land title and had allowed his in-laws to settle in that terrain, but did not live with them and was not present.77 Yet, the men accompanying judge Núñez did not listen to Candelaria’s explanations.

As soon as the judge finished reading the decree, the two ringleaders, Amadeo Achurra and Julián Alvarado, known perpetrators of other attacks, led twelve more horsemen to proceed with the removal by destroying the house. They swung their axes against the wooden posts that supported the kitchen, causing the roof to collapse on its own weight and shatter everything beneath it. The men then rammed the house with a beam tied to the back side of their saddles, smashing a wall. The building crumbled at once, but the elderly couple escaped in time. The attackers then loaded the carts with animals, furniture, and the couple, confident in their absolute impunity as a judge and three police officers bore witness without flinching. Attackers and officers then led the caravan of carts across the fields to the southern boundary of the Ñuble-Rupanco Company, the Coihueco River. Candelaria and Genaro begged their assailants to take them to a friend’s home some miles away, but instead they dumped them battered in an open field. Alerted by some neighbors, their son-in-law Adolfo found them the next morning. A cold, heavy rain had drenched them overnight, and they soon fell ill.78 The removal of the Saldivia couple from their land illustrates the violent dispossession of people in the hands of Rupanco employees under the auspices of some local authorities.

In 1912, police officers marched to Forrahue, a Mapuche-Huilliche hamlet to the northwest of Osorno, to remove its residents by order of a judge. Local villagers armed themselves to defend their homes with shotguns, a rifle, knives, axes, machetes, and sticks. Children were armed with clubs; women had basins of boiling water ready. A symbol of the power of modernization, police officers wielded Mauser rifles, which heavily contrasted with the locals’ improvised weapons. The clash between people and police resulted in fifteen Mapuche dead, including an eleven-year-old boy, all of whom were buried by the officers in a mass grave in the local cemetery.79

Other people in the Mapuche-Huilliche communities bolstered their identities as Indigenous Chileans to strengthen their applications for land titles. In 1912 and in light of the recent massacre at Forrahue, Ceferino Catrilef pushed the state government to protect him against the Ñuble-Rupanco Company. He heard that the Company, “exercising its overpowering action,” attempted to “remove [him] from his land in Coihueco Island and take it.”80 Catrilef argued the Ñuble-Rupanco Company had confused him with Sixto Catrilef. Hence, Ceferino desperately petitioned the Intendente of Llanquihue not to “facilitate or give orders to the police force to dispossess him from his property.” This would have been a serious mistake “given my quality of Indigenous person,” aggravated by “the recent disgraceful events in Forrahue.”81

The following year, a whole community filed a complaint against “the people occupying the lands in Rupanco and Coihueco,”82 because it belonged to them, “the natives that come to claim our blood loss in the battlefield of our fatherland.”83 Recalling the many times Indigenous peoples aided Chilean forces against the last Spaniard strongholds in the south, the petition drew similarities between colonialist forces that had displaced their Indigenous ancestors and corruption in the highest ranks of government. Under the purview of President Germán Riesco (1901-1906), argued the document, authorities granted the questionable lease to the Ñuble-Rupanco Company, while others jumped at the occasion of making some profit: “Everyone in the House [of Representatives in the Congress] owns this company and even President Ramón [Barros] Luco [(1910-1915)] […] out of fear became a shareholder in this company.”84 Indeed, shareholders included future president Luis Barros Borgoño, political rising star and future Minister of Finance Javier Ángel Figueroa, former senator Carlos Walker Martínez, and representative Francisco Rivas Vicuña.85 Sadly, the document has no signatures and no acknowledgement that it was sent up the ranks of government to investigate its matter.

Violence against Indigenous and non-Indigenous residents of Coihueco Island did not go unnoticed. In 1902, Alberto Stegmaier, first generation Chilean and future mayor of Valdivia, reported to the land inspector that government officials tried to remove Indigenous people from their lands. His concern stemmed from a paternalistic view of natives that typified them “credulous and timid” and that “many people in the frontier want to take advantage of these weaknesses.”86 As early as March 1905, only two months after the creation of the Ñuble-Rupanco Company, the newspaper El Llanquihue, published in Puerto Montt and distributed in all the region, denounced the extensive acreage granted by the government. “It is truly incredible,” it read, “that the government has ignored the rights of the many inhabitants who live there and has ceded it to a private individual.”87 A German newspaper in Valdivia reported in September 1905 that some residents in Coihueco Island had formed the “Anti-Rupanco Society.” Journalist Fritz Gädicke argued that some “shyster lawyers” organized this group with the express purpose of collecting dues from locals, holding dramatic meetings, and publishing hysterical pasquils in Puerto Montt. Even though the Anti-Rupanco group did not achieve anything and does not seem to have lasted long, it evidences a shared sentiment against the encroachment of the Ñuble-Rupanco Company.88 Another newspaper, La Prensa, from farther north, stated that “Coihueco Island is not a state-owned property that can be disposed of.”89 A magazine from Santiago, similarly, drew attention on Ceferino Currieco’s murder in Coihueco Island: “It seems that the [Ñuble-]Rupanco Company considered itself entitled to the properties of the Indians” and “sent armed people from its service” to destroy the house Currieco was building.90

Conclusion

In the opening vignette, a manager of the Rupanco Company arrived at the house of a long-standing family in Coihueco Island, the Curriecos, to remove them. The scuffle that followed condensed a history of spatial violence in southern Chile. The manager embodied decades of Chilean elites envisioning the south as an empty and backward region, while the Curriecos represented a long cycle of resistant adaptation to protect their lands. At heart, the delineation of private property following the law of 1866 underpinned the violent symbolic and physical displacements of residents in Coihueco Island.

The spatial violence in Coihueco Island stemmed from the racialized representation of space that informed the creation of private and public property decades earlier. Hence, the case study at hand exemplifies the long history of violence in the hands of colonization companies in southern Chile. Local authorities were sometimes complicit and sometimes they opened investigations, signaling the overlapping sovereignties that collided in marginal spaces. The forms of resistance displayed against the Rupanco Company echoes other strategies against land privatizations that typify the history of Latin America.

Today, resistance against the large estate in Coihueco Island persists. Although Salvador Allende expropriated the Ñuble-Rupanco Company in 1970, the government of Augusto Pinochet reversed this sale in 1979 and inaugurated a period of neoliberal production that facilitated more investment and more removals.91 Now and then, spatial violence in Coihueco Island epitomizes a longer history of state push to legitimize its sovereignty on Indigenous lands and the instrumental participation of companies, employees, and local authorities in it.