Introduction

According to the documentation produced by Chilean and European scientists, politicians, and missionaries, alcoholism on the Chilean frontier turned into a serious problem at the end of the nineteenth century.1 Scientists, above all physicians, and politicians assessed alcohol consumption-especially that of indigenous and mestizo rural laborers (rotos) who immigrated to Araucania during and after the military occupation of the region by the state (1862-1883), joining former frontiersmen (fronterizos) in search of land and work-as highly problematic and called for restrictions in the form of controls or increased penalties for excessive consumption.

Even though alcoholism was a widespread phenomenon in many societies, it started to become a serious health hazard for modern states over the course of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In a sense, drunkenness fueled the incipient sanitizing discourse of modern societies.2 Hence, Chile’s social question was significantly associated with alcoholism until well into the twentieth century: In the north, the drunkenness of mining workers;3 in the urban zones of central Chile, workers in taverns and chinganas;4 and in the south, vagrancy of rotos and drunkenness of indigenous people.5 In this context, a new form of social hierarchization has produced subjects like the rotos in Chile who, according to Rolf Foerster, are essentially characterized by indigenous and republican roots, indicating that they are mixed-raced people. Thus, the figure of the mestizo “roto aindiado” emerged, a free laborer employed in the factories and the countryside, who colonized the southern territories, coming from central Chile.6 In this sense, social problems usually went hand in hand with the stigmatization of rotos and indigenous people. This characterization of a particular social type of borracho also aimed to create the image of a degenerated society fallen prey to alcohol consumption, even causing economic problems, which was to be remedied. Thus, many intellectuals concluded that the state must begin to take care of problems in the field of public health.7

At the same time, the industrialization of alcohol production took hold of Chile in the second half of the nineteenth century, making for a promising economic boom. Marcos Fernández Labbé, in his book Bebidas alcohólicas en Chile, has explored and illuminated developments in different economic sectors related to the production, trade, and consumption of alcoholic beverages between 1870 and 1930. Above all, Chilean wine was characterized as a kind of national drink, which was to represent “the good taste” of Chile abroad as an export commodity.8 For example, almost 200 cartons of Chilean wines and liquors were shipped to the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1889.9

In addition to wine, industrially distilled alcohol-obtained from grains or potatoes, from which the strongest and equally cheapest alcoholic beverages could be produced-was declared to be mainly responsible for the “intoxication” of the Chilean society. Likewise, beer became part of the portfolio of beverages produced in Chile from the 1870s onward. Both liquor and beer were mainly produced in the urban zones of central Chile and were part of a small sectoral industrial growth in the south, in the provinces of Valdivia and Llanquihue. Chilean alcohol was henceforth to be exported abroad.10 To be able to regulate and control the production and sale of alcohol nationwide, the first Alcohol Law was passed in 1902 in response to this industrial boom.

Although the production of alcohol, its trade, as well as its consumption have always played a noteworthy role in the history of Chile’s southern frontier, as of yet, there is no specific research on alcohol and alcoholism in that context.11 In recent historical literature, the Chilean frontier is not conceived as a space of certain social practices and mobility of knowledge, stereotypes or imaginations in the field of medicine and public health. Research interest regarding the frontier has mostly considered the study of territory, questions of law or the landscape of the region.12 Meanwhile, in the history of science and in particular the history of medicine and public health, literature has specifically addressed the Chilean health system and the study of medicine in the urban areas of central Chile.13 Regarding histories of alcohol and alcoholism in Chile, studies by Marcos Fernández Labbé, Juan Ricardo Conyoumdjian, Patricio Herrera González and Juan Carlos Yáñez Andrade, among others, are essential research works that should be highlighted. Arguing from a social and economic history perspective, all of them focus on urban areas, especially in central Chile.14

Regarding the ethnic classification of indigenous groups and their relation to alcohol, a more deconstructive point of view is offered by Milan Stuchlik’s 1985 work on indigenous politics and the image of the mapuche in Chile. Stuchlik argues that Chilean elites developed five predominant discursive stereotypes of the che15 in different phases of history: “brave warriors” (until about 1840), “bloodthirsty bandits” (until about 1880), “lazy and drunken folks” (until about 1920), and “poor and needy indigenous people” (until about 1960) who “lacked education” (since 1960).16 In addition, Ericka Beckman, depicting and reaffirming the existence of Chile’s imperial fantasy during the annexations and occupations in the north and south, as well as through the acquisition of the Easter Island in 1888, argues that this “creolized imperial reason” had been structured around flexible and inconsistent discourses of race. On the one hand, Chilean elites affirmed the (relative) whiteness of Chilean rotos fighting against more indigenous soldiers on the Peruvian and Bolivian side during the War of the Pacific (1879-1883). On the other, elites declared the mixed-race character of rotos as responsible for their propensity to alcohol addiction.17 In fact, both studies show how an upcoming racial discourse had been intermingled with allegations of alcoholism among the rotos and the che.

Although case studies on alcohol and alcoholism in southern Chile are scarce and, if existent at all, concentrate on economic development,18 there is a large variety of primary sources and unique aspects to study, such as the discrepancy between practices and representations of alcohol consumption in the context of colonization, which make the Chilean frontier a curious case: The Araucania region belonged to the state after the military occupation of indigenous lands, completed in 1883. To develop, urbanize, and modernize the south, state actors recruited colonists to settle in these regions and foster the growth of cities such as Temuco or Valdivia. Missionaries also came to “civilize” the che, as well as foreign scientists such as engineers, geographers, anthropologists, and linguists, who sought to explore, chart, and study these areas and their people.19 According to Jorge Pinto Rodríguez, it has always been a space of encounters and otherness, in which representations of land, space, and territory were polysemic and disputed.20 Furthermore, the Chilean frontier can be characterized as a zone of “clusters of intensified change”21 during a short period at the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century. On the one hand, this was a time of a great increase in scientific “knowledge.” It was also a period of disappearing rituals and practices related to hygiene, in a region whose natural resources became subject to economic and political interests. By the 1930s, when the Chilean state established sufficient rule in southern Chile, the status of the frontier had effectively come to an end. In fact, the incorporation of the southern frontier into the Chilean state brought with it an important colonization process during the period under review that influenced the way in which different actors with interests in the Araucania read and classified indigenous and mestizo settlers.

This article aims to describe and analyze the perceptions and representations22 of alcohol consumption on the Chilean frontier in the context of the colonization process described above, by using primary sources produced as part of the activities undertaken by politicians, missionaries, scientists, and travelers. The objective is to present a case study of a less researched region in the field of the history of medicine and public health, depicting the perception of two social groups: the indigenous population and the Chilean colonists called rotos, who settled down at the frontier after the military occupation of the Araucania. The documents analyzed reveal that, from the perspective of contemporary accounts, the indigenous population as well as Chilean colonists became evidence of a degenerate society. They were portrayed and represented as drunks and victims of uncontrolled alcohol outbreaks. Regarding the indigenous population, this representation questions the image of the heroic and victorious che of the colonial period (called araucanos at that time), who successfully resisted the Spanish and the Republican military until the final occupation of the Chilean frontier in the 1860s and 1870s. Nevertheless, some primary sources evidence attempts to prevent the che from excessive alcohol consumption and to protect their culture and traditions. Others try to maintain the image of the heroic araucano of ancient times-at least for economic reasons. Drawing on the work of Jorge Muñoz Sougarret, as well as María Fernanda Vásquez and Marco Gaspari,23 among others, this article argues that the readings different observers formulated about alcohol consumption in southern Chile reveal how the intense process of occupation and colonization influenced social perceptions and social hierarchies. The reading and consequent perceptions generated among and by observers such as explorers, politicians, and missionaries-carried out between 1880 and 1930 as part of the incorporation of the territory into the state-resulted in the consolidation of socio-racial hierarchies that, in a sense, were already existent, mainly based on stigmatized perceptions of alcohol consumption. This activity was associated with a perceived moral decadence and uncivilized character of the rotos and the indigenous population, which, in the long run, had no other purpose than to facilitate or justify control over these groups by state representatives, the industry, landowners, and missionaries. While alcohol consumption was acceptable for certain populations, as evidenced by the simultaneous rise of the wine industry, it was reprehensible for the che and rotos.24 In this sense, perceptions, social practices, and the mobility of knowledge on alcohol consumption proved to be a highly disputed field in the context of colonization and the incorporation of Araucania into the Chilean state, as well as a way of consolidating social hierarchies.

I will present this argument in three parts. First, I will provide a brief overview of how indigenous people and their relation to alcohol were portrayed in the colonial era, to present the example of the che and their image as heroic people of ancient times throughout the investigation period. In Part 2, I argue that this representation contrasts the imagination and description of indigenous populations and rotos as drunken and degenerated people in the discourse on public health and modernity. In Part 3, I argue that, in accordance with discussions on alcohol consumption on the Chilean frontier by capuchin missionaries, indigenous people were turned into vulnerable actors in need of protection, whereas rotos became less spotlighted in scientific and political discussions.

From indio borracho to heroic araucano and back

To trace the processes of imagination and representation of indigenous populations regarding alcohol and alcoholism in the era of exploding sciences, the time frame is widened beyond the described period to include the colonial era and the early nineteenth century in the longue durée. Unlike the che, mestizo settlers already living in indigenous territories along the Biobío River and the coast (fronterizos) received less attention from the Spanish-Creole before the Chilean War of Independence (1810-1826). In this context, they can be considered a subaltern social group, although their significant number exceeded that of the che in different localities on the southern frontier, an area that stretched from the Pacific coast to the Andes and from the Biobío River in the north to the island of Chiloé in the south.25

Moreover, since the early colonial era, Spanish and Creole writers from across Spanish America associated indigenous culture with drunkenness. In addition, sources from after the Independencies in Latin America reveal the persistence of this discursive tendency. Hence, the Spanish and Creole discourse on indigenous alcohol consumption can be helpful to analyze the representations of indigenous culture in the post-Conquest period. Such a discourse-despite continuous denunciations from the sixteenth century to present-is not homogeneous in its understanding of drunkenness nor in its explanations.26

On the one hand, certain writers of the early colonial era described indigenous people as weak on alcohol, interpreting it as a sign of devilry. For most Spaniards, indios could not be good Christians. Thus, in 1618, King Felipe III enacted a law that allowed punishing a native with one day of prison and six to eight lashes “who misses mass on a feast day, or gets drunk, or commits another similar offense.”27 While in the early colonial period it seemed important above all to reduce alcohol consumption of indigenous populations so that they could become faith-abiding Christians, in the late colonial period the principle of order played a pivotal role: controlling the sale of alcohol and its consumption was intended to ensure the disciplining of the population.28

This changed significantly in the decades after the independencies from Spain, when Aztecs, Incas, and Araucanians “were evoked in countless works of propaganda that stressed not only their heroic qualities but also their commitment to the insurgent cause.”29 In the Chilean case, it was Alonso de Ercilla’s epic poem La Araucana, written in the sixteenth century, that most famously promoted the image of brave indigenous warriors-“so haughty, gallant and bellicose”30-resisting the Spanish conquistadores in early colonial times. Hence, the Araucana became the first reference across the independent Americas to symbolize the heroic attitude of indigenous people and to show their glory. Thus, in the interest of the elites, Ercilla’s work conveyed a different image of indigenous people: that of heroic warriors fighting against the Spanish Empire. In this context, also the roto became a key actor in Chile’s transition toward a truly modern and “civilized” state after the War of the Pacific (1879-1883) by being included as the “son of Araucanos” into an upcoming “mythologization of the pre-conquest indigenous past”.31 This image was contrary to the notion of indio borracho, who became a symbolic figure for barbarism during the nineteenth century that inhibited them from being civilized and being a civilized nation.

According to Luis Navarrete, secretary of the General Intendancy of the Chilean Army, and Conrado Rios, surgeon of the Military School and the War Academy in Santiago, alcoholism became a serious problem with the beginning of the occupation:

The ancient Araucania has been conquered by alcohol, rather than by the intellectual and civilizing efforts of man. The Indians have been and continue to be poisoned by the manufacturers of alcohol. Hardly a few thousand of that striving race whose glories were sung by Ercilla, their enemy, remain today.32

The return of indigenous people as “noble savage,” resistance fighters against the Spaniards and, thus, national heroes, did not last long as a narrative-at least not for the elites and representatives of the Chilean state. After all, it was the state that occupied and ultimately “pacified” the descendants of its own national heroes such as Lautaro or Caupolicán during the conquest of the south in the 1860s and 1870s. On a cultural level, however, this narrative was not going to disappear so swiftly and formed a counterpoint to the increasingly dominant discourse of a degenerated society.

Especially after occupations in the south, the image of southern Chile as “conquered by alcohol” influenced the fear of national elites of degenerating as a society and becoming sick, crossbreed, and mestizo-like, and therefore less civilized. The growing awareness of “sick societies” throughout modernity fostered the construction of a strategic comparison with less developed societies in non-Western countries by North American and European scientists, and in the Chilean case, by elites regarding the southern territories. At the same time, the Chilean state demeaned indigenous practices and rituals of hygiene within its own territory to outline the progressiveness of a seemingly “modern state.” High mortality rates, the spread of infectious diseases, and the professionalization of medicine were important factors for growing state intervention in health issues, which were finally formally enshrined in the Constitution of 1925.33

In the meantime, although indigenous religious and medical practices in rural areas were perceived as backward and “remains of barbarism,” especially by state actors, pharmacists and scientists in urban areas were consciously and gradually trying to include “indigenous knowledge” and, beyond this association with indigeneity, “the charisma of the exotic and the strange”34 in a growing global market. One example is the Aperitivo medicinal “El Araucano”, a liquor distilled by German pharmacist Fritz Hausser since the 1920s in Valparaíso with herbs from the south. At the same time, the indigenous population was excluded from a growingly popular “modern life”; social segregation and attempts to demarcate the center and periphery were its most aggressive consequences. However, indigenous practices generated great scientific interest within the Chilean and European academic world. Practices and properties were well known by healers and herbalists who kept this knowledge secret.35

In contrast to the aspect of “sick society” at the end of the nineteenth century as a phenomenon on a global scale, certain local and regional dynamics constructed the image of “sick people” instead: the che, who were seen as a degenerated ethnic group that had rapidly turned into the “shadows of past glories.”36 In order to resolve the contradiction between the heroic Araucanian, on the one hand, and the degenerate and alcoholic che, on the other, the glorious past of the indigenous culture was, in a sense, separated from their present. The glorious was associated-at best-with a pre-modern past in sources of the time.37 For instance, a German migrant, Carl Martin, who worked as a physician in Puerto Montt and depicted the landscape of science, medicine, and politics in Southern Chile and beyond, wrote the following in his book published in 1909: “It seems that none […] is under the illusion of being able to maintain the Mapuche people, once so proud. With few exceptions, these remnants of the ancient Araucanian people can be counted among the lowest class of people.”38

Martin helps build a broader understanding of different social and cultural relations between various actors in the frontier. His oeuvre opens a particularly fruitful space to study local and trans-regional connections between colonists, indigenous people, tradesmen, missionaries, and scientists, and how German migrants acted in such a heterogeneous setting. Similarly, Eliodoro Yánez, deputy of Valdivia, had also informed the Chamber of Deputies in Santiago in 1899 that “the robust Araucanians, after resisting for more than three centuries the thrust of arms and modern civilization, have fallen traitorously wounded by impure alcohol, without the public authorities having taken a step to avoid this inhuman crime.”39

Although Chilean elites connected modernity and civilization with European and North American societies during the nineteenth century, it was the European settlers-German and Swiss settlers in particular-who imported alcohol production to Chile and, especially, to the south. Thus, beer production in the province of Valdivia and beyond became a small but important sectoral industry and culture. The Anwandter brewery might be the best-known example.40 In 1904, Nicolás Palacios, a physician profoundly influenced by Darwinian and Spencerian evolutionism, wrote in his Raza chilena that “[i]t is well known that the custom of drinking is, in Europe, peculiar to the superior nations.” For Palacios, it is the discovery of the industrial manufacture of alcohol that “has lowered the price of this intoxicant to the point of allowing a day laborer to get drunk with a few cents.”41 The industrial production of alcohol on the frontier and in urban Chile (Santiago and Valparaíso) was closely linked to the immigration of German and Swiss settlers, tradesmen, and merchants. According to Palacios, they should not be in any relation to the indigenous population.42

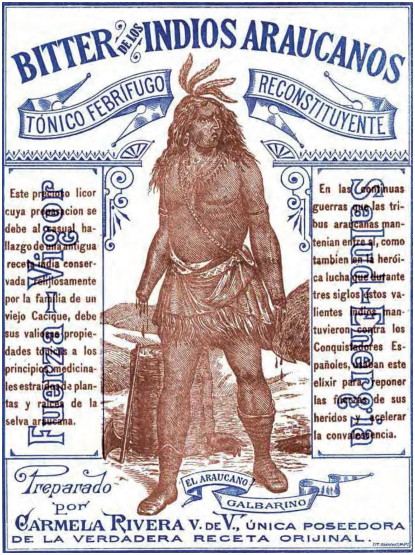

For instance, as mentioned above, German pharmacist Fritz Hausser opened a small business in Valparaíso with his own invented distilled and plant-based liquor called “El Araucano,” which is still sold in Chile and beyond today. Another example is the “Bitter de los Indios Araucanos,” a fever-reducing restorative tonic, prepared by Carmela Rivera V. en Valparaíso. As the brands’ advertisement declares, Carmela Rivera is surely “the only holder of the true original recipe” (see Figure 1).

Source: “Bitter de los Indios Araucanos”, trademark registered by Carmela Rivera, Valparaíso, 1899. Accessed 30 September 2021, available at Gramhir, https://gramhir.com/media/2107729953513839988

Figure 1. Bitter de los Indios Araucanos

Displaying the picture of a strong indio, naked except for a loincloth, opulent jewelry, and feathers, the brand underlines the image of the heroic araucano of a pre-independence glorious past.43 Although he stands there with his hands cut off (the axe leans in the background), which, according to Stuchlik, underscores the image of the bloodthirsty indigenous man in the nineteenth century,44 his gaze is determined and clear. Consumers are drawn to this heroic past with lettering on both sides of the painting that tells of the three-hundred-year struggle against the Spaniards. These inscriptions promise the buyers of this bitter power and recovery, which lies dormant in the secret of the ancient recipe:

This precious liquor whose preparation is due to the coincidental discovery of an ancient Indian recipe religiously preserved by the family of an old Cacique, owes its valuable tonic properties to the medicinal principles extracted from plants and roots of the Araucanian jungle.

In the continuous wars that the Araucanian tribes maintained among themselves, as well as in the heroic struggle that for three centuries they sustained against the Spanish Conquistadors, they took this elixir to replenish the strength of their wounded and accelerate convalescence.

Alcohol and plant-based remedies like Hausser’s “El Araucano” or Rivera’s bitter intended to be affiliated with indigeneity and the exotic. In 1899, when Rivera’s bitter was registered in Valparaíso, the figure of the heroic and strong indigenous cacique had already become so “strange” that costumers were encouraged to buy this “exotic” product as a promising remedy and cure for fever. Also, the promise of using an ancient and secret recipe that had proven itself for centuries aroused the interest of an urban Chilean upper class that learnt to enjoy this bitter at the turn of the century.

Rotos, che, and the scientific debate on alcohol consumption and public health

When Vicente Dognino Oliveri was a young man doing his military service at the frontier, he witnessed some tragic alcohol-related deaths. He tells of a soldier who died after two glasses of ron jamaica and of a sick man whom, as a budding physician, he could no longer help after drinking half a bottle of this potion. As these kinds of everyday cases are “examples of sudden intoxication that leave no room for doubt,”45 Dognino Oliveri pleaded for political change “mainly in the southern regions, where alcohol is abused to the point of threatening the organization and vigor of the race.”46

This awareness of a sick and degenerated society had been reflected on throughout the country by physicians, politicians, and pharmacists. Especially, descriptions of indigenous populations and rotos as drunken and degenerated people can be found in documents between the 1880s and the 1910s, when discourse on public health and modernity in Chile reached its peak. At the turn of the century, a physiological and social view of the harmful effects of alcohol on humans dominated the scientific environment. On the other hand, alcoholism was also perceived as a clinical pathology that associated drunken behavior with insanity and criminal tendencies. As the Revista Médica de Chile stated in 1892, criminality was interpreted as “a disease that attacks the social organism; it has its etiology, its own symptoms, its prophylaxis, its special treatment.”47 Accordingly, physicians like Salvador Feliú Gana declared alcoholism as a “more terrible scourge than cholera and the plague.”48 Even syphilis, “seen everywhere” and as a venereal virus “considered as the perennial source of the most varied diseases that came to present,” was not declared to be as dangerous for humans as alcoholism “that dominates the morbid scene.”49 From a scientific point of view, alcoholism was seen as a problem of the working classes in urban Chile and, therefore, a social problem. Furthermore, those who knew about the urban realities transferred their interpretations to the rotos in rural areas in the south.50 Just as the case of indigenous people, the rotos on the frontier were given very similar characterizations by their contemporaries. For instance, physicians like Adeodato Garcia painted the image of a strong working class from past times that became victim of alcohol and poverty, when he gave his speech at a Scientific Congress in Concepción in 1896: “The formidable figure of our historical roto chileno has passed into legend; instead, we see everywhere decrepit men, human pieces covered with rags, beggars dead of hunger and thirst, filthy wretches that smell of rot and aguardiente.”51

Ultimately, the image of a degenerate society that had long outlived its cultural prime prevailed. Alcoholism as a social problem became the subject of manifold observations at the frontier to study the manifestations, habits, and consequences of drunkenness: “Our roto drinks, first, his week’s wages and then converts work utensils to shoes into a few cents,”52 Luis Navarrete and Conrado Rios lamented. According to scientists and politicians, alcoholism, interpreted as a “social plague,”53 became mainly a problem in rural areas of the south and concerned, above all, men: woodcutters, craftsmen, and day laborers,54 that is to say, mainly people without land. “They move across the land like a consuming fire, leaving nothing behind but a pile of empty tin cans and broken bottles,”55 as Carl Martin described it in accordance with Isidoro Errázuriz, General Agent of Colonization and former Minister.

In fact, drunkenness on the Chilean frontier was mainly connected with working conditions and compensation. As Jorge Muñoz Sougarret has shown it, landowners (latifundistas), European colonists, and other employers in tanneries, distilleries, taverns, breweries or factories paid their workers mostly with alcohol-many of whom belonged to the indigenous population. Especially, industrial fabricated liquors became a common medium of exchange, as their prices remained stable for a long time.56 Here, German immigrants played a major role, as the small but growing industrial sector of breweries and distilleries was essentially dominated by them. Otto Bürger, a German zoologist and botanist who worked at the Universidad de Chile at the turn of the century, stated that men and women became more and more addicted to alcohol:

Drinking addiction increased with the emergence of distilleries in the province of Valdivia, which was initiated by German immigrants. Men and women soon preferred schnapps to any other drink: in the grocery store, on the march, in the hut, schnapps were their favorite refreshment. Above all, however, alcohol was drunk in banquets, in which women also took an active part.57

In the words of Jorge Muñoz Sougarret, labor would have been for many people on the frontier-settlers and the che-the only way to obtain freedom, through wage, which was the gateway to consumption and allowed individuals to gain for themselves independence and security as well as recognition and self-esteem in relation to others.58 Nevertheless, the poverty of the indigenous population and Chilean settlers, who counted as mestizos or aindiados for many writers,59 became part of the social question on the frontier. In fact, for the poor, being paid with alcohol could even mean a complete meal and replace water where there was no drinking water whatsoever.60 Some decades later, in the 1920s, scientists refuted this assumption, pointing out that alcohol could not produce force or could not count as a meal.61 Also in this context, land issues played an important role. At the end, those who managed to keep their property and did not emigrate to Argentina lived a very precarious life, always on the verge of losing everything.62

With the intention to provide help for poor populations in these regions, missionaries were called on, who had played an important role on the frontier since the Spanish attempt to conquer the region. In addition to evangelizing the indigenous population, civilization was especially important in the nineteenth century. Just as public health problems, moral issues were to be resolved through greater state intervention.63 The welfare of the poor also became an argument to legitimize missions on the frontier, where the state was only present in rudimentary form. Above all, for the Franciscans and-from the second half of the nineteenth century-for the Capuchins also, this task became a primary focus of their activities.64 Francisco Uribe, prefect of the Franciscan missions, wrote in 1884:

At the present time, it seems that the Indians no longer think of recovering their beloved savaged independence: perhaps because they see that it is impossible for them, in attention to their present state of poverty in which they have been left by the continuous expeditions of armed troops, which was necessary to make among them during their insurrections, or because they are persuaded of their inferiority. The fact is that now they are submissive to the authorities of the country, they listen with pleasure to the instructions of the missionary, they are interested in educating their children and that these learn some industrial trade, etc.65

Although this quote should not be given too much weight in the overall analysis, since it is primarily intended to justify the missions, it still shows how effectively poverty became a problem on the frontier. In fact, poverty and alcoholism mutually defined one another: “Alcohol has caused virile and strong races to change into weak and apathetic ones, incapable of resisting foreign domination,” mentioned Manuel Victoriano Cifuentes in 1899. “Therefore, it has rightly been said that alcohol did more to the pacificación of the Araucanians than the numerous Spaniards.”66

Even though many contemporaries identified alcoholism as a social problem, drunkenness was thought to cause other problems or-let us say-“real” diseases like tuberculosis because of “the frequent heavy soaking in the humid, stormy weather of southern Chile.”67 Also, madness, hysteria, and epilepsy were declared to be a direct consequence of alcoholism.68 High infant mortality rate, which became a huge problem in whole Chile at the turn of the century, is a particular example that shows how the supposed pathological and social causes of alcoholism have been used as arguments to explain these high rates in southern Chile. “The unsteady migratory life” of the indigenous population and the poor-miners, and rural workers-“as well as the ever-recurring change to which the nutrition of the families is subjected, primarily endangers the health and life of the younger children,” as explained by Martin, who also complained of the following: “In general, they do not observe any rule of a reasonable lifestyle. Drunkenness […], extremely inadequate housing, prejudices of all kinds, etc., give rise to a number of evils which hit the shelter-bound infants and smaller children especially hard.”69

In contrast to his compatriot Carl Martin, Otto Bürger distinguished between the indigenous population, which he described as very clean, and the lower classes: “The Araucanians have always bathed their children, which the lower-class Chileans do not do, and therefore, in spite of all lapses and negligence, infant mortality is lower than in the Chile of culture.”70 Hence, during the 1920s and 1930s, physicians and hygienists proclaimed a higher infant mortality and delays in development among families of drinkers, especially if the mother was addicted to alcohol.71 Furthermore, the discourse on infant mortality and life conditions on the frontier in the early decades of the twentieth century exemplify the role of nutrition in the context of alcohol consumption. A broadly accepted consensus in scientific circles indicated that the industrially fabricated aguardiente was the most dangerous with disastrous impact on local society: “In all the extension of the country, there are factories of this product, especially on the frontier, and it is also there where it is causing its greatest havoc,” wrote Dognino Oliveri in 1888, explaining that “this aguardiente is extracted from everything: potatoes, rotten wheat, decomposing flour, ryegrass, and even human excrement.”72

On the contrary, Eliodoro Yánez, deputy of Valdivia and advocate of the local industrial sector of distilleries in southern Chile, highlighted the importance of secondary sectors alongside these factories:

In the provinces of Valdivia and Llanquihue, an average of 15,000 pigs are fattened in various factories. To fatten these pigs, wastes from the distillation stills are used, which allows fattening them at little cost and selling the product of these butcheries at a relatively cheap price, provided especially to the working class of the north, which thus obtains a healthy and low-priced food.73

Beside the meat industry, the cutting of firewood on the frontier was largely dependent on distilleries in southern Chile, since firewood was needed for fuel in those factories in cities like Valdivia, Osorno or Puerto Montt. Not least of all, the manufacture of paints, varnishes, pharmaceutical products, extracts, dyes, and perfumery was also highly connected to industrial alcohol production on the frontier.74

The fact that large parts of the local population on the frontier lived in poverty, and in some cases even in hunger, ultimately reveals a paradox: Colonists, employers, and high-ranking politicians were more interested in the yield of alcohol distilled from grains and potatoes than in protecting the people whose lives had taken a turn for the worse due to immense alcohol consumption and the loss of their lands. In addition, according to Milan Stuchlik, fueling the stereotype of lazy and drunk che, especially by intellectuals and economic elites, rendered the advantage of blaming the indigenous population as being guilty of their own misery.75

Helping the poor: Alcoholism and land property issues on the frontier

The social status in the north of the country differs a lot from that in the south. Here, the initiatives often take unusual turns because the idea of quick fortune dominates the spirits. The incomplete division of property, the influx of a population animated by that purpose, favor violent clashes of conflicting interests, official improbity, and anarchy of society, thus moved by unhinged forces. The least apt to sustain this fight, of transient effects, is the Indian; hence the necessity to present him greater protection.76

Resulting from previous discussions and observations made by politicians, scientists, and physicians concerning alcohol consumption and alcoholism on the frontier, land property was declared the second issue in need of being resolved. Tomás Guevara, an ethnographer and teacher in Temuco, characterized the indigenous population as victim of regional conflicts, especially regarding territorial questions, as it appears in the quotation at the beginning of this section. Claiming protection and economic advancement for indigenous culture, Guevara affirmed that “their moral improvement” was to become “a natural consequence.”77 Like many other intellectuals of his time, Guevara portrayed the indigenous population as infantile and unevolved in comparison to others. In this context, the consumption of alcohol played a significant role, generating a “true pathological issue” in local society.78 For Guevara, “barbarians” neither changed nor developed for centuries; because of clashing with modernity, they would soon disappear.79 In fact, the relation between alcohol consumption and questions of property on the frontier turned out to be a serious matter.80

Although a first alcohol law was passed in 1902, it did not provide any protection for indigenous peoples or other groups. Six years prior, Joaquín Talavera argued that a law would finally lower crime statistics, reduce cases of hysteria and epilepsy, and liberate hospital beds as well as places in insane asylums.81 For decades to come, a discussion about measures to prevent alcoholism among the indigenous population dominated the political stage. On the one hand, physicians like Talavera held that the main purpose was to improve the welfare of this population and their health, through restrictions on alcohol consumption. Others supported the alcohol industry, in particular the winegrowing business in central Chile, and the idea that the function of the state was to collect taxes for the treasury. However, the first law of 1902 emphasized the control and supervision of alcohol distribution and consumption. In fact, public drunkenness was penalized, and the distribution of alcoholic beverages in liquor stores was strictly controlled.

Despite regulations, production was not affected by new tax burdens, as most taxes were passed on to consumers rather than producers. During the following years and decades, criticism on legislation flooded public discussions throughout Chile.82 In any case, during the study period, neither political actors nor scientists linked alcohol consumption on the frontier to land issues in a way that would have helped improve the lives of Chilean settlers and the che. In concrete terms, it was not until 1898 when a law was passed in favor of national colonization. Additionally, by the late 1920s, the process of restructuring property under state control, first through various legal entities, involved the transfer of public lands at low cost to landowners (latifundistas) in the central and south-central zones-through auctions that encouraged speculation and the expansion of large landholdings-and then to foreign and national settlers. In this process, mestizo-like settlers were stripped of their land titles and indigenous people were dispossessed and displaced. Thus, the new settlers received titles to lands that fronterizos and rotos had already successfully cultivated for decades. This process made the Chilean settlers willing to do whatever necessary to save their lives, either by submitting to tenancy or trying to overcome their misfortune, at least momentarily. Thus, many of them became mediators, interfering in a conflictive way with indigenous communities. Consequently, crime and vandalism provoked more land abandonments and “constructed wide and irreconcilable geographical, social, and moral frontiers.”83

Furthermore, it was the Bavarian Capuchin missionaries, in support of the Italian Capuchin mission, who were called to the Araucania by the Chilean state in 1896 to “civilize” the Chilean settlers and, especially, the che. In particular, Father Sigifredo de Frauenhäusl became one of the “advocates” of the indigenous population.84 In their first annual report of 1904, the Capuchins wrote to a German-speaking readership:

Unfortunately, however, the simple way of life and the firm unity which once made the Araucanian so strong, have now largely disappeared. Drunkenness and other vices introduced by intercourse with the whites have in many cases enervated the people physically and mentally, and the Araucanian, once so jealous of his freedom and his old furrow slice, now not infrequently sells his field and cattle to buy brandy for their price.85

Much like Guevara, the author portrayed the indigenous population as strong, proud, and free people who had been “protected” for centuries by nature;86 all of this was about to disappear by alcohol, among other things. Only a few months later, in February 1905, Father Sigifredo wrote two letters to Luis González, federal prosecutor in Valdivia, and to Secretary Ludovico Barra, denouncing the deceitful businesses of Guillermo Angermeyer, a colonist of German descent, with indigenous people who were given liquor in return for giving up their lands. “Usually, it is vagabond Indians who sell the rights they have to a property,” wrote the missionary. Well-connected to federal actors of the region, he made a difference between those che who were in the mission’s charge-the “good” ones-and those who were negotiating with Angermeyer for alcohol.87 Especially, the urban zones and cities on the frontier, such as Valdivia, Osorno, Puerto Montt, and the fast-growing Temuco, with their great number of liquor stores were declared to have a dreadful impact on indigenous culture. For example, Burcardo de Röttingen, prefect of the Capuchin mission, wrote that there were always che in Valdivia because of legal proceedings at court about their lands: “They roamed the streets, usually staying overnight in the liquor stalls, where, of course, they got intoxicated. They did not know where to spend the night. To remedy this, I decided to build a simple house in the garden, where they would not disturb us.”88 Apart from letters, chronicles, reports, and their own periodicals, the Capuchin missionaries also used photographs to document life on the frontier. Similar to the way ethnographers put on stage indigenous culture, they published a photograph taken by B. Hermann of two young indigenous men; one was described as “uncivilized,” while the other one was characterized as “urbanized” (see Figure 2).89

While “urbanized,” in the narrative of the missionaries, alluded to being deformed and ruined, “uncivilized” meant that there were still possibilities to become “civilized” in the way how Capuchins interpreted a civilized person. In fact, the Capuchins looked for opportunities to “save” indigenous people by obligating them to a Christian life. As Martín Correa Cabrera recently summarized, it was primarily the state that was responsible for the process of dispossession, impoverishment, and violence against the che starting in 1862.90 In contrast to state representatives, certain missionaries helped the che to defend their lands or taught them how to read and write. Like many other actors at the time -Franciscan missionaries, scientists, or politicians-, Capuchins also declared that moral education was the best remedy against alcoholism.91 In the long run, their proposed learning opportunities made indigenous people on the frontier increasingly dependent on others.

Source: “Ein uncivilisierter und ein ‘städtischer’ Indianerbursche,” in Jahres-Bericht über die Tätigkeit der bayerischen Kapuziner in der Araukaner-Indianer-Mission in Chile. Den Wohltätern und Freunden der Mission gewidmet, edited by Burcardo de Röttingen (Altötting: Druck von Hans Büttner in Altötting, 1904), 17. Photography by B. Hermann.

Figure 2. “Ein uncivilisierter und ein ‘städtischer’ Indianerbursche”

Conclusion

While in urban areas of central Chile such as Santiago or Valparaíso alcoholism was mainly associated with poverty, on the frontier it was declared, in first instance, a problem among indigenous people and rotos. The separation of the che’s “glorious past” from their present lead to the creation and consolidation of their image as degenerated, drunk, and-in the end-poor and dispossessed indigenous people. This also applies to their mestizo-like neighbors, the so-called rotos. Hence, the analysis of the studied documents shows that, within the process of occupation and colonization on the frontier, there had been an emerging narrative convergence between poorness and the debilitated condition of the che and mestizo settlers. Thus, alcohol consumption and alcoholism became a supporting argument for the so-called “degeneration” of the indigenous people and the rotos in the discourse of the turn of the century. In fact, alcohol on the frontier became the main vehicle for the stigmatization of these populations, as it happened with the sick and poor.

In this context, maintaining the glorious past and the image of a strong araucano benefited different actors-state representatives, (foreign) scientists and intellectuals, traders, and missionaries-but not the indigenous people themselves: for example, traders profited from the “exotic” label and indigenous “secrets” of ancient times by selling plant-based bitters, and missionaries “protected” the che by invoking their heroic past. Although Capuchin missionaries like Sigifredo de Frauenhäusl, among others, tried to save the che from being robbed or exploited by Chilean or European settlers, their help meant new dependencies, which produced new stereotypes based on the alleged poorness and helplessness of the indigenous population, who were perceived and represented as people in need of moral education and salvation by the hands of Europeans.

Hence, the use of the past was also at stake in the process of consolidating new social hierarchies, during the colonization of the frontier and its incorporation into the state territory. It is this colonization and land redistribution that gave rise to the observations presented here about the che and rotos. As evidenced, alcohol had been introduced as an instrument used in the occupation and appropriation of lands, which gave impetus to private property. While settlers, especially from German-speaking parts of Europe, and Chilean traders built small businesses in the field of agriculture, food, and beer industry, a huge group of poor and-in many cases-landless settlers, as well as indigenous people tried to find their fortune on the Chilean frontier at the turn of the century due to newly established social hierarchies, simultaneous stigmatized perceptions, and dynamics of exclusion.