Introduction

The Jesuit priest Joseph Gumilla highlighted the agricultural and commercial potential of the Orinoco basin in the northern South American kingdom of New Granada in his widely read 1741 book El Orinoco Ilustrado.1 Gumilla, determined to raise awareness of the region’s natural riches, encouraged Spaniards to settle in the fertile lowlands of the Orinoco River and establish villages and cattle ranches. The region was located in the eastern part of the newly established Viceroyalty of the New Kingdom of Granada and included provinces where Jesuit fathers had established missions since the 1570s. In Gumilla’s image of agrarian riches and the Orinoco River, we find a discourse that envisioned the newly created viceroyalty as a hub of agriculture and trade. He noted that in those lands, “everything invites cultivation, and this country offers rich and abundant fruits everywhere.”2 Gumilla’s utopia attempted to persuade the Spanish crown of the value of the Orinoco region’s natural resources to gain additional missionary, economic and military support.

Along with Gumilla, other members of the clergy, the military, and the civil administration worked together to establish Spanish territorial control of the Orinoco region and gain royal support. Julián de Arriaga, a royal official, sent a dossier to the Council of the Indies detailing how different corporate powers collaborated to defend Spanish sovereignty in the region. It included a geographic description, a map created by the governor of Cumaná and several territorial descriptions written by the Catalan Capuchins who oversaw the region’s missions. Finally, the document contained a few letters and maps by José de Iturriaga, the military commander of the Limits Expedition, who was tasked with demarcating borders between the Spanish and Portuguese crowns.3 Colonial bureaucrats on the Orinoco’s outskirts portrayed the region in their writings to make it visible to reformers in Madrid. Their territorial descriptions and maps gave Spanish bureaucrats a spatial sense for establishing Bourbon economic governance in the eighteenth century.

Colonial administrators in the Orinoco region did not explore and describe the colonies’ geography for their own sake. They studied and wrote about the landscape searching to turn it into a natural resource. In a context of inter-imperial competition, they applied the framework of political economy to figure out how to transform the natural riches of their territories into wealth for the Spanish Crown. Imagining how to connect sources of wealth-crops, fisheries, mines, flour mills, textile workshops-and revenue collection hubs to internal fluvial and terrestrial means of transportation and sea outlets was central for this endeavor. The principal aim of royal officials in the peripheries of the empire was to energize domestic trade, hinder foreign incursions, and strengthen the region’s participation in Spain’s commercial empire.

The case of the Orinoco region exemplifies a more extensive history of administrative, economic, and territorial reform in northern South America during the eighteenth century. This Spanish empire’s area of the Viceroyalty of New Granada was characterized by a mountainous topography, vast inter-Andean valleys, plains in the east, and Atlantic and Pacific coastal regions vulnerable to foreign incursions. During this period, the Spanish Crown implemented its most radical territorial reform in centuries, with long-term implications for republican territoriality. The Bourbon crown laid out a renewed plan for imperial reform in what then were the northernmost reaches of the viceroyalty of Peru with the establishment of the new viceroyalty of the New Kingdom of Granada between 1717 and 1723 and then again in 1739.4 The reform aimed to increase territorial control over northern South America and the Caribbean, increase revenue, and protect the overall territorial integrity of the American colonies. Over the century, colonial officials devised numerous of plans to order the territory and achieve cohesion as a condition for wealth production.

In a set of inscriptions on New Granada’s natural world, its geographic characteristics and sources of wealth, colonial officials imagined and worked to transform the viceroyalty of New Granada-present-day Colombia, Ecuador, Venezuela, and Panama-into a wealthy and geopolitically safe political entity. The following questions occupied the time and work of bureaucrats in the colony at this time: How could colonial wealth be safeguarded from intruders from other empires? How could the peripheral areas of northern South America be sources of wealth for the Spanish Monarchy? How could the Andean region be integrated with coastal cities? Colonial officials created political economy discourses that rendered conflicting territorialities in northern South America: a cohesive colony that was regionally differentiated. While the contemporary literature on political economy focused on empire competition, the Bourbon centralization and economic and administrative reforms led to competition between Spanish colonies. Inter-colonial geopolitical and economic conflicts erupted as a result of Bourbon territorial reform. Moreover, while territorial integration and wealth generation were difficult to achieve on the ground and were full of tensions among provinces within the viceroyalty, bureaucratic fiscal networks enabled it to function as an administrative whole that linked coastal and Andean areas, as well as the colony, to the Greater Caribbean and Europe.

An era of territorial organization guided by the precepts of political economy led to the establishment of the viceroyalty of New Granada. Bureaucrats aimed to forge a connected, wealth-producing colony in northern South America in response to the challenges that foreign incursions imposed on Spain’s territorial control and wealth production. By exposing bureaucratic knowledge production practices, I shed light on the peculiarities of New Granada’s economic governance during a period of remarkable economic growth in the Spanish empire.5 Although the Iberian empires have long been neglected or occupy an ambiguous place in the history of capitalism and globalization,6 the Spanish colonization process addressed here led to an enormous acquisition of wealth in Europe and to the insertion of northern South American commodities and staples into the global markets.7 Imperial reform and its negotiation across colonial outposts forged bureaucratic practices based on the production of knowledge about the territory, which impacted wealth production, geographical imaginaries, and territorial disputes. This type of knowledge that shaped territoriality and capital accumulation deserves a place in the histories of global capitalism.

1. Imperial Reform, Political Economy, and Knowledge Production

Recent contributions have begun to uncover the larger shifting geopolitical configurations that influenced the pace and character of the reform that resulted in the establishment of the viceroyalty of New Granada. According to historian Francisco Eissa-Barroso, its creation reflects profound changes in the understanding of the monarchical rule and the role and responsibilities of the king. He claims that reform did not begin in Spanish America and was not driven by Spanish American interests. The reforms stemmed, he asserts, from the king’s belief that his main responsibility “was to provide his subjects with good economic government and conditions for development.”8 However, this imperial-centered inquiry into reform in the empire’s periphery does not glance beyond imperial politics inside Madrid’s court. The idea for a new viceroyalty came from the metropolis, but the creation of the administrative muscle to make it possible was the work of hundreds of colonial bureaucrats. Separated by an ocean of distance, colonial officials were the ones who faced and dealt with the on-the-ground challenges of administering the colonies. They worked to represent and transform New Granada into a territorial, economic, and administrative unit with a long-term vision of integration and wealth creation.

Establishing the viceroyalty of New Granada was just the beginning of an era of territorial rearrangements that emerged as byproducts of the science of political economy. Developing from the study of power, this field of learning developed over time under the heading of “political economy.”9 The imperatives of fiscal survival in a hostile international environment, according to this conceptualization, made economic knowledge necessary. As Europeans embraced this knowledge during the seventeenth century, state competition served as the backdrop for eighteenth-century political economy reflection.

Northern European historians tend to favor a scale of analysis that confines political economy as a science that emerges in the texts of European thinkers and merchants. They trace the circulation of influential political economy books and their translations across Europe to demonstrate how Europeans studied political economy in order to emulate Britain’s economic and political success.10 Recent contributions, on the other hand, have looked at the emulation of foreign political and economic ideas in eighteenth-century Spain and its peripheral American colonies across the Atlantic.

Ideology, geopolitics, and knowledge practices influenced the Spanish reformation program in the colonial peripheries. Historian Gabriel Paquette has divided the intellectual foundation of the Bourbon reforms, beginning with Charles III’s accession to the throne, into three parts: regalism, political economy, and international rivalry considerations.11 Imitating, reflecting on, and correcting foreign models became central to Bourbon political thought, which evolved into a “syncretic ideology of governance.”12 Paquette shows that emulation became essential to state survival as the Bourbon state was refurbished with a new common language of reform, that of political economy. Last but not least, he contends that general government reform hastened the integration of the empire’s outposts, like New Granada, into the global economy.13 Paquette’s research has made it possible to comprehend the complex conditions under which political economy knowledge was developed and negotiated among colonial institutions during Bourbon rule. I expand Paquette’s perspective on intellectual history by focusing on texts and knowledge production strategies that are less frequently discussed in the literature on imperial reform and political economy.

The Spanish Empire has a long history of knowledge-gathering practices and descriptive geography. The empire was built on constantly pursuing information about the territory and its population. The production of relaciones geográficas consisting of questionnaires to gather information about the land and its people, was a Spanish policy since the sixteenth century.14 Through these devices, the Crown requested information to control space occupancy, taxation, and population distribution.15 As Arndt Brendecke has argued, the objective of the Spanish court’s efforts to gather empirical information about the periphery during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was not to maximize the Crown’s political rationality. Instead, its objective was to reinforce bonds of loyalty between the king and his colonial subjects.16 In the 1710s, Spanish reformers started to suggest that the nature of royal authority was not simply to provide order and justice but that the king had to promote the material welfare, common good, and economic and cultural progress of his subjects.17

In contrast to the first two hundred years of colonial rule, during the eighteenth century, the collection of knowledge began to coincide fully with a reform program formulated to exploit it.18 A utilitarian conception of the land and its resources laid at the foundation of imperial reform in the Spanish monarchy.19 Imperial governance and its main objective of increasing wealth needed the constant production and flow of documents from peripheral areas of the empire to main colonial cities and then to the metropolis. Historian Sylvia Sellers-García has argued that in an effort to overcome distance, officials in Madrid could not “see” the Americas, therefore “they relied on American officials to make it visible and knowable.”20 In this reform agenda, one of the central problems of colonial state-building was making space legible.21 This consisted of ordering the population and the landscape to help simplify state functions such as taxation, security, and wealth creation. In fact, an essential component of Spain’s effort to govern, demarcate, and extract wealth from its vast transatlantic dominion consisted in gathering information about the land and its resources. The paper technologies of empire-making were vital components of the social history of knowledge, colonial place-making, and political economy embedded in Spanish colonialism.

The attempts to imagine and consolidate a viceroyalty in northern South America can be traced in a set of bureaucratic documents such as maps, economic improvement projects, administrative reports and petitions, geographic descriptions, and natural histories. These documents are chorographic in nature. In the so-called “Diccionario de Autoridades” of 1729, chorographia is defined as “the description of any kingdom, country, or particular province.”22 The roots of the chorographic tradition are found in classical antiquity. While it entails writing about a country or region, it alludes to the representation of space and place in the framework of spatial history. Chorography is then a non-neutral endeavor in which royal officials use descriptions as part of a process of turning unfamiliar spaces into familiar places for economic, political, and military ends. The construction of the territory of the viceroyalty of New Granada during the Bourbon era unfolded as part of Spain’s tense relationship with other empires, shifts in colonial policy, and situated practices of political economy knowledge production.

2. The Economic Government of America and the Viceroyalty of New Granada

The Spanish monarchy ascribed its preoccupation to creating stable and clearly delimited borders for the empire and its colonies to a defensive policy aimed at counteracting the expansion of other European empires. The Treaty of Utrecht, which concluded the War of Spanish Succession, resulted in several territorial and economic rearrangements. While the Treaty protected Spain’s overseas territories, in Europe, Spain ceded Gibraltar, Minorca, and the areas inherited from the Habsburgs in the central and northern parts of the continent, including Italian regions.23 Spain also ceded the asiento de negros, the monopoly over the slave trade, to Great Britain in 1713.24 The Treaty also consolidated the international recognition of the Bourbon monarchy, which attempted to dismantle the previous two centuries of Habsburg rule, based on federal autonomous provinces.25 As a result, the new monarchy sought to create a uniform juridical framework for the Spanish Empire and its colonies to recover from the perception that the empire was failing.26

Unlike early Spanish colonialism, which emphasized incorporating its subject population into its vision of Catholic Christianity, the Bourbons highlighted the economic government of America. The strategic plan for the Economic Government of America written in 1743 by the Minister of the Secretaries of Treasury, the Navy, War, and the Indies, José Campillo y Cossío, contained the basic tenets of the reforms. It reflected renovated visions of the role and purpose of the Spanish monarchy, put in place since the beginning of the century and even since the second half of the reign of Charles ii (1665-1700).27 The work remained in manuscript form until its publication in 1789, yet it influenced eighteenth-century reforms.28 Campillo y Cossío’s text characterized Spanish political economy: his plan was pragmatic, addressed local concerns, and took into account successful foreign economic practices.29 Campillo envisioned a plan through which the Spanish crown would increase the empire’s population and fortify strategic navigation routes and territories. He described the economic government as “good policing, the arrangement of commerce, the manner of civilly employing men, the cultivation of the land, the improvement of its fruits, and finally, everything that leads to the greatest benefit and usefulness of a country.”30 Thereafter, the Council of the Indies-the primary reformation organ of the Spanish Empire in the Americas after 1737-directed all its efforts to the economic recovery of overseas possessions. Imperial reformers started to consider the colonies of the New World as an “integral territory of the Monarchy.”31

In the case of the Viceroyalty of New Granada, a rural agricultural economy in which gold mining played an important role in shaping the colonial economy,32 reformers considered jumpstarting mining, promoting trade, and combatting smuggling.33 With this aim, the Bourbon crown laid out a renewed plan for imperial reform in the northernmost reaches of the Viceroyalty of Peru. They established a new viceroyalty between 1717 and 1723. However, financial needs to sustain wars in Mediterranean Europe led Spanish reformers to extinguish the viceroyalty in that last year. Over a decade later, the upsurge of tensions between Spain and Britain, stemming from the Treaty of Utrecht, led to the restoration of the viceroyalty in 1739.34 As Eissa-Barroso has explained, in the decision to restore the viceroyalty in 1739, “reformers gave extensive consideration to the specific ways in which establishing a viceroyalty would encourage the economic development of northern South America.”35 Transforming these territories into an agricultural and trade hub, a revenue-producing colony, and integrating them into the Spanish commercial empire became a priority of the Spanish crown during the second half of the eighteenth century.

For this exercise in spatial imagination to succeed, emulation of French political economy proved crucial. The creation of the viceroyalty in 1717 came with a series of reforms introduced by the Italian priest Giulio Alberoni, the Italian cardinal and statesman in the service of King Phillip V since 1715, which significantly altered the form of government of the Indies.36 Alberoni’s reform was multifaceted and, in some aspects, mimicked French political economy, which started in France under Jean-Baptiste Colbert, often regarded as the leading figure of French mercantilism. Historian Jacob Soll defines ‘Colbertism’ as the idea that a large-scale state needs to centralize and harness encyclopedic knowledge to govern effectively. This knowledge, which can be both formal and practical, he adds, could be used to master the material world and assert claims in favor of the monarchy.37

The proposal for a new viceroyalty included a knowledge-gathering strategy. The king directed royal officials to prepare reports to be sent to Spain that described the proposed viceroyalty’s provinces and people. Colonial officials wrote extensively about the northern South American territories they governed. The Council of the Indies sent petitions to America regularly, requesting that royal officials map, evaluate, and control potential sources of wealth for the empire.38 By producing chorographic texts such as natural histories, petitions, maps, administrative reports, and geographic descriptions, bureaucrats in the colonies promoted the rhetoric and policy of large-scale imperial reform. These documents reflect the imperial state’s search for supreme authority within the empire’s periphery. Furthermore, these texts show that colonial officials negotiated political economy ideas vis-à-vis specific colonial geographic and geopolitical realities.

On the eve of the eighteenth century, the New Kingdom of Granada epitomized the weaknesses of the Spanish Empire. A patchwork of geographically disparate regions, constantly infiltrated by Portuguese, Dutch, and British smugglers, made it challenging to control. In addition, native sovereignties established trading networks with other Caribbean empires in their borderlands. The area included within the viceroyalty’s proposed jurisdiction had mountainous landscapes. The Andean mountain range crisscrosses the central Neogranadian regions, splitting into three distinct chains. This caused the topography of this area to be rugged, making circulation arduous. The dispersion and small-scale settlements, the difficulties of internal transportation, and the scattered nature of the colony’s mining all hampered the viceroyalty’s economic growth.

While historically New Granada had developed mainly as a subsistence and domestic agricultural economy and as a gold-producing colony, the reforms broadened the scope of economic improvement. The Spanish monarchy shifted from a vision of empire that tended to base the state’s power on acquiring markets rather than bullion. Promoting trade, agriculture, and fighting contraband became the central tenets of the project to increase administrative efficacy and reverse the perception that the crown’s power had been eroded. Royal bureaucracies supported the development of export economies in cacao-producing cities, such as Guayaquil and Caracas. According to Bourbon policy, economic viability and cohesiveness in the region depended on strengthening royal bureaucracies while improving internal communications, military defense, trade, and fiscal networks. Reinforcing commercial ties between the Viceroyalty and Spain were all steps towards strengthening imperial administration.

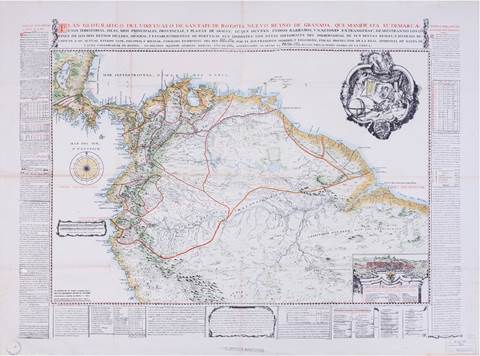

This reformation drive required the reorganization of administrative jurisdictions. The Real Cédula of August 20, 1739, ordered the erection of the viceroyalty including the jurisdictions of “Choco, Popayan, the kingdom of de Quito and Guayaquil, the province of Antioquia, Cartagena, Santa Marta, Rio del Hacha, Maracaibo, Caracas, Cumana, Guayana, Islands of Trinidad and Margarita, and Orinoco River, provinces of Panama, Portobelo, Veragua and Darién.”39 (See Map 1). The territorial reform included fiscal rearrangements that attempted to centralize the administration of the Royal Treasury in the hands of the viceroy, who resided in the capital city of Santa Fe de Bogotá.40 The new bureaucratic apparatus was expected to harness fiscal revenues more effectively by subordinating local and provincial officials to the authority of a viceroy-the image of the king in America. In addition, responding to inter-imperial rivalry, the reform of military jurisdictions in coastal locations led first to the separation of the province of Venezuela from Santo Domingo and later from the Viceroyalty of New Granada. Despite detaching the territories of Venezuela, Neogranadian territorialization advanced significantly throughout the century. For instance, from the viceroyalty’s creation until the early 1800s, the expansion of imperial structures and policies of land redistribution led to an increase in the number of provinces or governorships. Within the provinces, new parishes and towns were created.41 This territorial reform stemmed from renewed visions of Spanish colonialism that sought to counteract the growing influence of the British and make Spain rich and powerful again.

While different scales of analysis should help explain the unfolding of territorial reform, the literature on political economy centered on the competition among empires dominates the tales of empire-making in the Atlantic world. Competition, however, also emerged at the inter-colonial scale, and jurisdictional conflicts were a common feature in the Spanish polycentric monarchy.42 In tandem with foreign incursions-such as the British attack on Portobelo in 1739-Bourbon territorial reform unleashed inter-colonial geopolitical and economic conflicts with long-lasting consequences in South America. For example, the change in jurisdiction impacted Peruvian mercantile interests. In a set of letters directed to royal officials in Madrid, Peruvian authorities and merchants protested the separation of Panama and Guayaquil from Perú.43 In 1741, Antonio José de Mendoza Caamaño y Sotomayor, Viceroy of Peru, raised his concerns regarding the trade of Peruvian goods at Portobelo, located on the Atlantic side of the Isthmus of Panama.44 The viceroy complained because Peru’s trade primarily flowed through Guayaquil and Panama, which would now belong to the newly created viceroyalty. Mendoza Caamaño also noted that due to the distances and broken terrain between Santa Fe and Portobelo, the resources and governmental ordinances from Santa Fe would arrive late, to the detriment of Spanish trade.45

Decades later, in 1779, the controversy was still current as José García de León y Pizarro, President of Quito’s Audiencia, revisited the issue to attempt to segregate Guayaquil from the newly created viceroyalty.46 Later on, a royal decree in 1803 ordered the annexation of Guayaquil to the Viceroyalty of Peru. The rationale for this decision was distance and the interest in facilitating control of fiscal revenues and sending defensive support from Lima to Guayaquil, as opposed to Santa Fe.47 The conflict between Peruvian and New Granadian leaders over the jurisdiction of Guayaquil-a pivotal outlet to the Pacific Ocean-grew during the struggles for independence. Territorial reform affected inter-imperial political economies, revealing the contested nature of colonial jurisdictional change and igniting a long-standing conflict over the southwestern border of the viceroyalty. In the short term, the authorities of Santa Fe responded and directed their efforts to legitimize the existence of the new viceregal territoriality.

To this end, the conjunction of bureaucratic practice and mapping projects contributed to shaping New Granada’s conceptual and imagined territory within South America and the entire empire. Bureaucrats in Santa Fe readily worked towards inscribing the space of the viceroyalty in chorographic texts. They sought to advance commercial and territorial visions of the provinces to improve the newly created viceroyalty’s position within the empire. In the framework of the Bourbon reforms, efforts were made to establish territorial cohesion in New Granada and the rest of the colonies. This brought about the creation of cartographic representations, as well as a comprehensive reformation of the fiscal administration. By the early 1770s, colonial reformers sought to depict the viceroyalty as a cohesive administrative and geographic space, distinguished from Perú. They unleashed a knowledge-gathering campaign guided by the spirit of the Enlightenment and the tenets of the economic government of America.

3. Wealth Creation, Cartography, and the Search for Legibility

In December 1770, Viceroy Pedro Messía de la Cerda requested local officials throughout the kingdom to produce reports on the territories under their command. The request asked colonial officials to describe their pueblos (villages), cities, villas (towns), and places within their jurisdiction, as well as any borders differ due to ecclesiastical and spiritual jurisdictions. The request also asked for rough estimates of the number of inhabitants and their circumstances, provincial incomes, and, if possible, a map to “facilitate knowledge of the places described.” 48 This information was required by Messía de la Cerda to assess the kingdom’s situation, first in its smaller territorial units and then as a whole.

The effort was supported by a network of royal bureaucrats from the fiscal, military, and ecclesiastical administrations. Local governors, fiscal administrators, and clergy members wrote their own reports. Although it is unclear how many local officials submitted chorographic reports, evidence of report-gathering processes within specific provinces exists. For example, in response to the viceroy’s request, the report titled “General State of the Cities and Towns of Cauca, 1771” was created. On January 31, 1771, the Governor of Popayán, Joseph Ignacio Ortega, redirected the viceroy’s petition to provincial officials. Ortega distributed the request to royal officials of the cities and places within his governorship. Local administrators responded to the petition. The same request was sent from different cities to Quiebralomo’s mining centers (reales de minas), where the priest (cura doctrinero) responded. Local bureaucrats were part of the network of chorographic knowledge that circulated from the colony’s outskirts to Santa Fe de Bogotá, the administrative center.49

Few local governments had access to trained surveyors or cartographers. In addition, moving across the New Kingdom of Granada was a costly and challenging endeavor. Therefore, most of the local chorographic texts presented descriptive information about local territories gathered through the experience and observations of local administrators. Viceroy Messía de la Cerda attempted to craft his relación de mando (government report), relying on information provided by local administrators. He felt that his report lacked detail. For this reason, he commissioned the Crown Attorney, Protector of Indians, Judge, and Preserver of royal incomes (fiscal protector de Indios, juez y conservador de rentas reales) of the Real Audiencia of Santa Fe, D. Francisco Antonio Moreno y Escandón, to compose yet another general compendium of the state of the Viceroyalty regarding civil, political, economic, and military matters. Moreno y Escandón, an official of the viceregal capital, produced the text entitled “State of the Viceroyalty of Santafé, New Kingdom of Granada” (Estado del Virreinato de Santafé, Nuevo Reino de Granada). Along with the report, he ordered the creation of a map of the viceroyalty, entitled Plan Geográfico del Virreynato de Santafe de Bogotá, Nuevo Reyno de Granada in 1772.50 The map, which he referred to as a “geographic plan,” included information on the territorial demarcation, islands, rivers, provinces, forts and main cities. 51 Moreno spent some time gathering information for his report and faced difficulty compiling reliable information on distant provinces.

Bureaucrats in the periphery frequently complained about a lack of “substantial knowledge” of their kingdom’ distances, incomes, peoples, and topography.52 According to royal administrators, the scarcity of accurate information led to failures in political decision-making and hampered economic governance. Moreno y Escandón, for example, emphasized the kingdom’s “defective” settlements. He added that not knowing the number of inhabitants, “qualities, class, funds, and way of life,” and the state of commerce stymied good governance. For him, this disorganization was also reflected in the fact that “the houses, streets, and public places are not numbered.”53 This principle of partitioning the urban landscape into numbered individual registries simplified the work of officials in charge of ensuring tax collection in the quest for legibility.54

Making the Viceroyalty of New Granada into a revenue-generating colony, like Peru and New Spain, began with representing its material conditions. The “Geographic Plan” of 1772 reflects the Spanish monarchy’s desire to create a unified image of all American possessions (See Map 1). 55 The map depicted the viceroyalty as a single unit, with a thick line clearly separating it from Peru and New Spain. 56 The chart and chorographic texts described its natural wealth as subject to human intervention. The map focuses on fiscal and demographic data, as well as the potential for future wealth in the space occupied by the viceroyalty. The central legend at the bottom of the map states that its goal is to present the viceroyalty’s current state and potential to determine the most appropriate measures for its improvement. In doing so, the map assessed the causes and origins of the viceroyalty’s backwardness. The geographical chart also mentioned the “deterioration of [the Viceroyalty’s] trade, its abundant and valuable agricultural fruits, and mines.” 57 Although cartographic representations typically aim to present physical space in an economical manner, Moreno y Escandón included a significant amount of text on the map. His textual additions mapped the viceroyalty’s administrative structure. He charted urban and rural spaces as a record-keeping bureaucrat and translated them into fiscally relevant numbers along a narrative of potential wealth.

Source: Plan Geográfico del Virreinato de Santafé de Bogotá Nuevo Reyno de Granada […] Por el D. D. Francisco Moreno, y Escandón…”. Biblioteca Nacional de Colombia (bnc), Bogotá-Colombia, Colección Archivo Histórico Restrepo, Fondo Mapoteca, 262, F. Restrepo 36.

Map 1. Plan Geográfico del Virreinato de Santafé de Bogotá Nuevo Reyno de Granada

Moreno y Escandón chose to represent a landscape ready for human intervention -one quantifiable in incomes, partitions, and people. In his efforts to systematically organize the viceroyalty’s accounting information geospatially, the map included in its margins “Notes relative to the state of the Royal Treasury” (Notas relativas al estado de la Real Hacienda). A series of statistical charts, which framed the map, displayed the viceroyalty’s territorial divisions, revealing the imposed administrative order. The chart for military governments included calculations of salaries assigned to each military jurisdiction. It also counted the number of cities, villages, towns, places, and indigenous towns. The section also collects information on missions, including the religious orders in charge, the number of towns, missionaries, and indigenous peoples, and the cost of maintaining them. Finally, the chart shows the number of tributary indigenous peoples from each jurisdiction and its urban populations (vecinos). The same information, such as salaries and the number of cities and towns, is displayed on the map for each political government within the Audiencias of Santa Fe and Quito. The written narrative in the charts, along with the cartographic representation of the viceroyalty, contributed to the containment and order of the colony’s space. Furthermore, references to a few scientific expeditions and the use of prior geographic knowledge place the Plan within the context of Bourbon Enlightenment science.

Royal bureaucrats used Enlightenment science to help the Spanish fiscal-military state by demarcating the viceroyalty’s space. During the century, the development of fiscal-military states was linked to the Atlantic context.58 The rivalry between Britain, France, and Spain necessitated the use of resources and abilities that the colonies provided. The map’s thick, well-marked borders created the illusion of a bounded space, one claimed by Spain but constantly threatened by foreign incursions. The map appears to show fixed viceregal frontiers and a stabilized colonial space but it also includes areas of potential or ongoing conflict and weakening imperial control. The map indicates areas where foreigners could invade the territory, such as the coast of Veraguas, “where the pirates of the Mosquito [coast] enter, fish for tortoiseshell, and plunder the province.” 59 This reflects royal concerns about the viceroyalty’s vulnerability compared to the strength of other empires in alliance with independent indigenous groups.

Spanish reformers considered the possibility of partially integrating independent indigenous groups into colonial society through trade. Moreno y Escandón emphasized in his more extended report the hindrance posed by indigenous uprisings to the viceroyalty’s progress, and the perils associated to English alliances with indigenous communities residing on the Mosquito coast. 60 The Plan contained a section on viceregal religious missions and asserted that the majority of provinces within the viceroyalty were adversely affected by “barbaric Indians, (...) which hinder trade,” and frequently established friendships with foreign enemies.61 He devoted several pages to this issue on the report.62 The report includes a citation of information provided to Spanish authorities by an Englishman apprehended near Cartagena on the Caribbean coast. The Englishman had used the false Spanish name Alejandro Velasco. Foreigners taught Neogranadian authorities about developing trade networks and English settlements on the Mosquito Coast. In the late eighteenth century, apprehensions regarding their territorial expansion into Calidonia and the Gulf of Darien escalated.63 Moreno y Escandón believed that Englishmen, in alliance with autonomous indigenous groups, could easily invade the gold-producing provinces of Chocó and Antioquia from the aforementioned area. Moreover, he added, indigenous populations could assist enslaved mining laborers in their quest for emancipation. The fear was primarily justified by the fact that gold mining “is the only product on which the entire viceroyalty depends.”64 He also mentioned that the navigation of the Atrato River in this area had been forbidden for Spaniards since 1730, further exposing the region to vulnerability, compounded by the absence of fortifications. In brief, the persistence of sovereign indigenous polities, their coalitions with foreigners, and the closure of the Atrato River constituted a threat to gold extraction. According to royal officials, the viceroyalty had the potential to stimulate both internal and external trade, prevent infiltration of agents from other empires, and connect coastal territories with Andean hinterlands.

4. The Paradoxes of Andean-Caribbean Relationships

Knowledge about the territory was useful but limited in promoting the idea of the viceroyalty of New Granada as a unified administrative, economic, and geographical unit among bureaucrats and merchants. Creating a unified domestic market while competing with other empires in was a major focus for royal administrators and a crucial aspect of the local political economy. Historian Regina Grafe argues that Eli Heckscher’s comment that mercantilism was “primarily an agent of unification” is often overlooked in historiography.65 Grafe explains that Heckscher viewed mercantilism as a set of ideas and practices aimed at state formation and the creation of an integrated domestic market, rather than solely focused on international competition.66 This section expands on Grafe’s critique of the scholarly emphasis on mercantilism’s foreign trade dimension. It explores the tensions that arose from efforts to integrate the Andean hinterlands and Caribbean coastal areas through military defense, trade, and fiscal interconnection.

Escandón’s Plan barely depicts New Granada’s viceroyalty economic connections with the Greater Caribbean region. The maritime borders with the British, French, and Dutch empires in the Caribbean significantly impacted its economic culture. The report stated that the viceroyalty had minimal trade activity and only produced few agricultural products, such as cacao.67 The map and text do not reference the illegal trade’s impact on colonial wealth and harm to the Royal Treasury. His limited attention to coastal trans-imperial commercial flows resulted from his interest in conveying a vision of territoriality and viceregal power that is centripetal. He emphasized the creation of an integrated internal market and the symbolic and bureaucratic core of the viceroyalty in the city of Santa Fe de Bogotá.

The map includes a panoramic view of the urban center of Santa Fe in the lower right section. In the view we see a valley of organized houses and buildings with the Cordillera in the back. The city’s coat of arms displays a crowned black eagle holding a pomegranate in each claw, surrounded by more pomegranates. This portrayal of Santa Fe as an administrative, commercial, and learning center, as well as an ideal European-like landscape, demonstrates its position as an administrative and learning core. Moreno y Escandón proposed an education curriculum reform, which replaced theological philosophy with Enlightenment natural philosophy.68 The city led the way in incorporating Newtonian sciences into education and housed the Royal Botanical Expedition (1783-1808) and the first Astronomical Observatory in the Americas, built in 1803. Creole intellectuals in the capital led the expansion of the public sphere and the circulation of public discourse on political economy.69

In contrast to Escandón’s portrayal of New Granada, Manuel de Anguiano’s geographic-military description of Cartagena in 1805 emphasized the city’s significance as a component of the viceroyalty’s economic governance.70 The port city housed a state customs house and a merchant’s guild later in the century (Consulado).71 The city of Cartagena played a significant role as a mercantile hub and a primary center for the distribution of slaves, with the customs office serving as the focal point of these activities. Anguiano’s interpretation of the landscape of the viceroyalty of New Granada extended the defensive responsibilities of the province of Cartagena to include the protection of the region that connected the Caribbean and Pacific regions of the viceregal territory. Anguiano provided an interpretation of the landscape in relation to Cartagena’s role in defending Neogranadian resources. This interpretation was based on a historical context of recurrent Dutch and British incursions in the gold-rich province of Chocó.

Cartagena was designated as a military jurisdiction due to policies aimed at assigning the strategically positioned city with the responsibility of safeguarding the viceroyalty against external threats. Following the British capture of Portobello in 1739 and the attacks to the city in the following years, Cartagena experienced a golden age in the development of military fortifications that persisted for the entirety of the century.72 The reorganization of New Granada resulted in the establishment of a new territorial hierarchy that pertained to both war and trade matters. As a part of the reform, a politico-military division was established, which had already been included in the decree that established the viceroyalty in 1739. The general commanders of Caracas, Cartagena, and Panama were appointed as the governors of this division. The significance of Cartagena as a defensive entrepôt and commercial center of the kingdom was amplified during the reorganization of jurisdictions and the establishment of the Consulado de Comercio in 1795. The Consulado represented the regional interests of the city’s commercial elite but encountered significant opposition from the merchants of Santa Fe.73

Despite the conflicting portrayals of the respective roles of Santa Fe and Cartagena in the viceroyalty, and the competition between their commercial elites for trade dominance, fiscal territoriality under the viceregal system established a reciprocal interdependence between the Andean cities and Cartagena. Paradoxically, the challenge of safeguarding the northern gateway to the kingdom against autonomous indigenous groups and external invasions played a role in Cartagena’s fiscal reliance on the interior provinces of the viceroyalty. A number of fortification initiatives within the city were granted substantial financial support from the monarchy. The Spanish government implemented a fiscal system that directed the surpluses of local provincial economies in the Andean region towards supporting the crucial military defense infrastructure along the Caribbean coast. A network of bureaucrats linked towns to regional revenue collection centers by transporting fiscal remittances from Andean cities to the defense outpost of Cartagena. Coastal regions, especially in the Caribbean, aimed to acquire not only commercial benefits but also royal currency.

According to historian Rodolfo Meisel, an analysis of Cartagena’s fiscal incomes from 1751 to 1808 reveals that “the situado became the vital sustenance of the public finances and economy of Cartagena.” 74 Meisel notes that the situado, which involved a series of intra-imperial money transfers, was regularly utilized to support strategic military outposts such as Cartagena, Santa Marta, and Guayana. During the tenure of Viceroy Solis (1753-1761), the fiscal surpluses obtained from the treasuries of Honda and Mompox, in addition to the fiscal remittances received from Quito and Santa Fe, were utilized to improve the fortification system and to provide sustenance to the troops stationed in Cartagena. The fiscal network that facilitated economic transactions between the Andean hinterlands and the Caribbean coast served as a conduit for the exchange of not only monetary resources but also other valuable commodities. Before 1795, the transportation of royal safes from Quito to Cartagena was managed by merchants who engaged in the buying and selling of goods en route, thereby stimulating the local economies of the regions through which they passed.75 Throughout the century, the fiscal network had been reinforced by the introduction of new fiscal bureaucracy and the establishment of additional local fiscal institutions. The Royal Treasury faced significant challenges due to Spain’s precarious authority over the borderlands of the viceroyalty. The Cajas Reales were responsible for collecting revenues not only for local improvement projects, but also for larger imperial needs such as wars in Europe, limits’ expeditions, fortifications and military sustenance.

Interdependence between the Andean and coastal regions was limited by competing commercial interests. As demonstrated by Alfonso Múnera, merchants hailing from Santa Fe presented arguments that their economic interests were in conflict with those of Cartagena and held divergent perspectives on the viceroyalty’s development.76 The construction of transportation routes to the coast was deemed a priority by Santa Fe’s Consulado during periods of flour scarcity, to ease the movement of their products. However, the king appointed Cartagena as the facilitator of the internal transportation routes and economic growth of the viceroyalty. The Consulado in Santa Fe lodged a complaint, stating that Cartagena exhibited a lack of interest in the progress of the interior provinces. This, coupled with the crisis of flour supply, posed a significant challenge to the efforts of making wheat the foundation for agricultural advancement in the viceroyalty. Moreno y Escandón’s report highlights the tension caused by the traffic of foreign contraband flour into the kingdom, which was consumed in Cartagena at the expense of its production and trade in the interior provinces.77

Despite the controversy that resurfaced during the independence process, Andean cities continued to depend on Cartagena’s pivotal role as a commercial and defensive stronghold. In contrast, Cartagena turned on the fiscal surpluses generated by Andean cities. Throughout the century, the Andean and Caribbean regions of the viceroyalty developed a complex interdependent relationship that allowed for a somehow integrated domestic market. Despite Cartagena’s significant role as the protector of The viceroyalty of the New Kingdom of Granada and its strong connections to the broader Caribbean area, both in terms of spatial imagination and administrative functioning, it continued to be financially reliant on the hinterland provinces and therefore remained closely linked to Andean urban centers.

Conclusion

In the eighteenth century, gathering information about the territory, its topography, natural resources, and potential economic prosperity became fundamental to bureaucratic practice and economic governance. The portrayal of New Granada’s provinces aided in the design and imagination of entire landscapes in which the viceroyalty emerged as a potentially rich, integrated, yet regionally fragmented space. Bureaucrats, military men, cartographers, and missionaries drew maps and wrote about the landscape and its resources in a non-neutral endeavor that involved debating the boundaries and integration of territorial units and how to generate wealth for the empire. In this sense, the discussion of knowledge production, colonialism, imperial reform, and political economy presented here became crucial for European capital accumulation.

A spatial history of the creation of the Viceroyalty of New Granada thus reveals how language and mapmaking rhetorically served to transform space into place. In this process, the representations of the viceroyalty made it a legible, resource-producing colony not only for the Spanish but also for other European empires. As this article has shown, the production of knowledge in the form of chorographic texts tailored by bureaucrats was inextricably linked to the creation of wealth in Spanish overseas colonies and Europe. As historian James Torres argues, during this time, the viceroyalty experienced “an interlinked process of economic growth, with the linkages of gold and commodity export”. This growth, based on regional specialization and commercialization, allowed consumers to access goods from Asia and Europe, thereby allowing the region to expand its markets.78

While this was a period of economic growth and global interconnection, many of the visions of territoriality and political economy projects never materialized as colonial officials had imagined them. On the other hand, this type of mapping gave a definitive purpose to ongoing governance, commercial networks, imperial and creole aspirations, and longstanding visions of territoriality, which were often quite fragile illusions in practice. However, New Granada’s geopolitically unique position, internally topographically dislocated and permeated by foreign incursions, provides a unique opportunity to delve into the geographical imagination and conceptions of space that were so central to the negotiation of imperial reform and capitalism before to the collapse of Spanish imperial rule in northern South America.

Chorographic political economies were central devices of imperial reform, and the search for colonial wealth that laid the foundation of production and territorial integration occurred in colonial outposts, not in intellectual treatises in Europe. As Cardim et al. argue, the Iberian Monarchies were polycentric in the sense that “they allowed for the existence of many interlinked centers that interacted not only with the king but also among themselves, thus actively participating in forging the polity.”79 Reporting back to Santa Fe or Spain, governors, clerics, oidores, military men and viceroys themselves sought to convey a spatial understanding of particular regions within the empire. While local political economies set out to advance the possibilities of connecting a city or town with certain rivers or sea outlets, larger conceptions of the Viceroyalty of New Granada as a territorial unit proved difficult to render a sense of territorial cohesiveness. The same was true on the ground vis-à-vis a reality of insurmountable topographical obstacles that impeded fluid communication among provinces. Whether imagined or on the ground, the integration of the viceroyalty from the economic, defensive, and administrative points of view rendered discourses of regional difference, along with utopian representations of territorial integration and knowledge of political economy. Although bureaucratic, fiscal, and military networks enabled the viceroyalty to function as an administrative whole that linked coastal and Andean regions, the tensions between the main cities of Cartagena and Santa Fe illustrate paradoxes in the making of an integrated and harmonious viceregal territoriality in the dawn of the Spanish Empire.