Introduction

There are two prevailing modes of understanding the development of capitalism in Ming-Qing China. The first one consists of examining China’s economic deficiencies in the Ming-Qing periods vis-à-vis the capitalist development patterns in Western Europe, thereby explaining China’s lag in developing capitalism and the “Great Divergence” between advanced parts of Western Europe and China. The second type emphasizes that different development paths existed in the East and the West. As it suggests, the process of commercialization and capitalism in Ming-Qing China cannot be disproved by simply alluding to features that can be attributed to its particular path. Meanwhile, due to the close relationship between finance and capitalism or the modern economic transformation that ensued in the past 200 years, the role of finance has attracted a great deal of research even though there is considerable disagreement over the empirical evidence.1 Finance also plays a key role in different development theories.2 Similarly, the function of finance has further received attention in both schools of thought described above.

In the first mode, the higher interest rates in China, compared with Europe, is a central discussion point. Since the 1930s, scholars have argued that “usury” in traditional China not only produced a polarization between the rich and the poor in rural areas but also inhibited industrialization.3 The latest evidence in this regard comes from the research of Wolfgang Keller et al.4 They have shown that the degree of grain market integration in China and Europe was relatively close on the eve of the Industrial Revolution.5 However, they found that interest rates drawn from grain prices in 1770-1860 were higher in China than in Britain and that the interest rate market in China was much less integrated than in Britain.6 Thus, they try to provide a financial explanation for the “Great Divergence” between China and Britain. However, the meaning of their findings is still unclear since the interest rate obtained from grain prices is an insufficient proxy when trying to determine actual prices in the capital market, especially given the complex interest rate structures in both China and the West as described by Jean-Laurent Rosenthal and Roy Bin Wong.7 In fact, in recent decades, Chinese historians have studied several account books and letters of financial institutions such as lending shops (zhàng jú) and exchange banks (piào hào)8 in the 19th century. They have unearthed that these institutions’ lending rates to merchants were decreased to a level no higher than 10% annually, sometimes even as low as 4-6% per year for prime customers.9 This level of interest rates for commercial finance is still higher than that of Western European countries during the time period in question but significantly lower than the popular impression in the existing literature. For example, in the monumental work of Sidney Homer and Richard Sylla, they notice interest rate changes during the Ming-Qing eras, but still argue that high-interest rates were prevalent in China when it opened to Western enterprises through treaties during the mid- and late 19th century and that the low-interest rates in treaty ports, e.g., Shanghai, benefitted from modern Western financial institutions, such as banks, rather than the development of native finance.10

At the same time, both the discussion by Alexander Gerschenkron that the British Industrial Revolution did not depend on the banking industry and Yoshiro Miwa and J. Mark Ramseyer’s emphasis on trade credit during the Meiji Restoration in Japan tend to show that financial development can take different forms or paths in different countries.11 Similarly, in the second mode, even though compared to Europe, China had higher interest rates and its financial institutions were less formal, adherents of the California School, including Kenneth Pomeranz and R. Bin Wong, have argued that shortages of capital could be overcome by intensifying personal and non-market methods, e.g. kinship networks.12 In a more detailed study, Joseph P. McDermott specifically explores how clans were involved in business activities by trust funds, based on historical materials from Huizhou.13 However, in the field of Chinese financial history, for scholars working on the Ming-Qing period, the more discussed phenomenon is the evolution of financial organizations, such as pawnshops, native banks (qián zhuāng) and exchange banks (piào hào),14 while the reduction of commercial interest rates is inextricably linked with the activities of these institutions. This development was not a novelty in global history and suggests that the role of exclusive institutions such as kin structures and clans should not be exaggerated.

Therefore, neither the decline in commercial interest rates and the evolution of impersonal institutions in the realm of the Ming and Qing dynasties, which were similar to those in the West, nor the presence of special characteristics, e.g., the absence of long-term capital markets, should be ignored. It is more challenging to explain such a mixed process than merely focusing on one aspect of that process. Similar work has been done in studies about commercialization or “Smithian Growth” during Ming-Qing times.15 However, there is no clear consensus on financial development due to the scattered nature of the available data and the difficulties in interpreting them. Based on scholarly progress in recent decades, this paper will explore changes in commercial finance regarding financial organization, financial technology and commercial interest rates in order to discuss their meaning and significance for understanding processes of “Smithian Growth” in China from the 16th through early 20th centuries.

1. Evolution of financial organizations

China’s commerce and market economy peaked during the Song dynasty (960-1279) but tended to decline from the Yuan (1271-1368) to the early Ming period (1368-1435). Then, the market economy began to recover via the loosening of the in-kind fiscal system during the mid- to late Ming dynasty (1436-1644).16 Meanwhile, foreign silver flooded into China from Japan and the New World since the 16th century, which also stimulated commercialization, as discussed by Richard von Glahn.17 Some scholars, e.g., A.G. Frank in the English-speaking academic world, highlighted the positive role of monetization on economic prosperity,18 but this has caused much controversy. For instance, one view suggests that the silverization of currency began with domestic reforms, especially the silverization of the fiscal system, and the subsequent inflow of silver from Japan and Latin America only provided conditions for the sustainability of such reforms rather than stimulating the market economy directly.19 Considering the decline of other currencies, such as copper coins, and the absorption of silver in non-market sectors, it is doubted whether the silver from abroad was adequate to make up for the shortage of currency in circulation during the late Ming period20. However, a recent analysis of key evidence from Huizhou’s land price series suggests that the silverization of currency in the late Ming era positively contributed to commercialization and the deepening of monetary relations.21 Furthermore, the recovery of finance soon followed suit.

The most noticeable development at that time was the boom of the pawnshops. Although pawnbroking had a long history, some significant new features appeared in the late Ming. First of all, the capital of pawnshops largely derived from cross-regional and powerful commercial capital stocks. The capital that was accrued in great businesses, e.g., salt, cloth and grain trades, entered the pawnshops on a large scale. The prominent merchant groups, such as Huizhou merchants, also focused their capital operations on pawnshops. Secondly, not only commercial capital but also the social wealth of the gentry, officials and other groups flowed into the pawnshops.22 Finally, pawnbroking became one of the greatest businesses in cities, and pawnshops became the primary financial institution in the late Ming period. Although the basic business of pawnshops was to provide microfinance for urban residents, they concentrated on regional trade hubs. For example, Beijing had thousands of pawnshops, and Linqing, a trade hub along the Grand Canal, also had hundreds of pawnshops. Traders could get working capital from those shops, using commodities as collateral, and travellers turned to them for money exchange.23 All these features indicate that pawnshops played the role of a financial hub in allocating social capital in the late Ming.

An important prerequisite for the development of pawnbroking is the existence of institutions that allow capital to be concentrated across regions. In the late Ming period, one magistrate of the Shexian County in Huizhou complained that many Huizhou people traded in other parts of the country, which led to frequent lawsuits outside Huizhou, and officers here had to cooperate with their colleagues in other places, including controlling the residents involved.24 Although this increased the work of Huizhou officials and even got relatives of the outside merchants into trouble, it meant people dealing with Huizhou merchants would not have to worry too much about them running away with their money. Their family fortune and relatives in the hometown would be involved once there was a lawsuit against them, even if it was quite uncertain how much would be paid for that. We could call this the Chinese-style “unlimited liability” if this frequently used concept holds true. Such institutions continued until the late Qing period, as cases of Huizhou, Shanxi, and Guangdong merchants, etc., showed on occasion. On the other hand, the locals could also oppress non-local merchants. In the late Ming period, non-local merchants took an active part in litigation, which shows that informal institutions, e. g., the practice of “collective punishment” described by Greif, took an important role.25 However, the judicial practice also revealed a sympathetic tendency to non-local merchants by imposing joint liability on the local middlemen.26 The judicial process, however, was costly, and injustice was difficult to escape in the real world. Still, it shows that there were reactions to the institutional demands of merchant groups operating across different regions in the Ming-Qing eras.

Would it be accurate to describe financial developments during the late Ming period as capitalist? In the decades before the 1980s, Chinese students tried to identify “sprouts of capitalism” in Ming and Qing China, focusing on the type and size of employment. But no consensus was achieved, and scholars’ attention turned to the market economy. As Braudel has demonstrated, the market economy can be divided into different levels while the “highest-level”, that is long-distance trade carried out by notaries, financiers and other skilled operators, is closest to his understanding of capitalism. Following this definition, he argues that “only the very lowest levels of trading worked effectively” in China due to the obstructions of the imperial administration.27 This view is also echoed in Wu Chengming’s influential work.28 However, as was shown above and will be discussed further, the financial sector in late Ming times had reached the higher level described by Braudel, and the government played an active role in it.

Unfortunately, prolonged warfare, famine, and heavy taxation caused by the pressure of military expenditure seriously damaged commerce and finance in the late Ming and early Qing periods. Although the crisis also led the state to pay more attention to merchants’ financial resources, the fiscal efforts of the Ming court did not lead to military success; the direct negative effect of civil wars and wars between the Ming and Qing dynasties was much more severe and contrary to the fiscal-military state model prevalent in Europe during the same period. However, when the social order was stabilized, the financial sector revived quickly and took on a new shape in the 18th century. In contrast to the late Ming period, when pawnbroking was prevalent, the native banks (qián zhuāng) dominated this round of development in the 18th century. With the rising status of silver as the main currency, organizations in charge of the exchange of silver appeared at the end of the Ming dynasty. After the bimetallism of silver and copper coins stabilized in the 18th century, native banks (Qián zhuāng) and silver shops operating currency exchange and silver casting also flourished. They thus entered the field of money supply and further established this role through financial activities, including issuing various bills, setting regional monetary standards and creating credit. Especially in Beijing and commercial ports, there were also specialized lending shops (zhàng jú), that were operated mainly by Shanxi merchants. Meanwhile, pawnshops lost their dominance in finance, although some were also adjusted to fit the needs of the time, including currency exchange and paper money issuance. Pawnshops extended their business activities to the hinterlands rather than concentrating on large cities, which had the effect that their services generally shrunk and were now limited to regular consumption loans.

As a result of the acceleration of financial developments since the 18th century, the operation of exchange banks (piào hào) peaked in the first half of the 19th century. Their service was not limited to the exchange-remittance business. By allocating capital over long distances, they became the hub of financial markets in many cities and trading ports, and their business scale was most significant among traditional financial institutions. More importantly, a series of innovations in financial organization were introduced within exchange banks.

First, a credit system was formed where loans were settled according to the cycle of long-distance transportation of silver (biāo qī). Via this system, merchants daily operated their businesses on credit. They jointly and periodically cleared their debts when silver arrived at specific ports. It greatly saved the cost and time of silver transportation and increased the circuit velocity of money. The prototype of biāo qī emerged in Beijing at the end of the Ming dynasty when the cyclical transfer of silver by armed men was used in the long-distance trade of textiles along the Grand Canal.29 At the beginning of the 18th century, biāo qī with a ten-day clearing cycle under the support of the provincial government appeared in Liuhe town, Shanghai’s predecessor. There, various merchant groups traded in bulk, dominated by soybean goods transported by large junks (shā chuán) from northern China.30 This trade had a profound impact on the development of Northeast China (Manchuria), but it was also crucial to the development of agriculture in the Yangzi Delta since soybean cake became an important commercial fertilizer. By the 19th century, the trade-financial network of Shanxi merchants stretched across Northeast, Northwest, Central China and other regions, and their biāo qī was also linked with the long-distance bulk trade of tea, tung oil, fur and other commodities.

Secondly, Shanxi merchants entered into credit relations with settlement intervals based on biāo qī, which generated the standardized interest rate market.31 The market of monthly interest rates was formed in Beijing and Suzhou around the same time. In the mid-19th century, the account books of zhàng jú in Beijing showed that lending rates to shops almost entirely fluctuated with respect to interest rate market quotations.32 Since the mid-and late 19th century, the Native Bankers’ Association in Shanghai organized currency trading and settlement among financial institutions to establish a daily market for currency exchange and inter-bank lending. The most famous one was the interest rate market based on the two-day inter-bank call loan. The existing letters of exchange banks show that interest rates and other market information from around the country were frequently exchanged and letters were used as signposts for capital flows.33 These standardized rates became actual price signals, which marked the maturity of the cross-regional capital market.

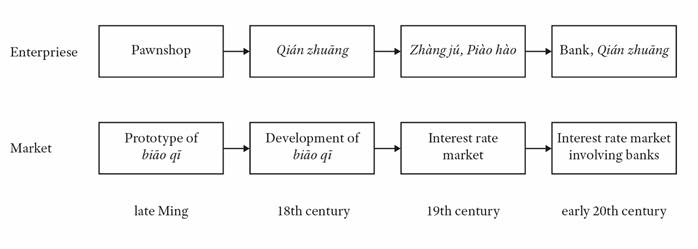

In the late 19th century, Western practices increasingly influenced the domestic financial sector. The greatest influence was the entry of new financial organizations, especially modern banks, which gradually gained a considerable market share from traditional financial organizations by the beginning of the 20th century. However, their competition was not only based on the survival of the fittest. On the one hand, modern banks recruited experts from traditional financial organizations, and their spatial distribution was closely correlated. On the other hand, and more importantly, traditional interest rate markets, including the inter-bank call loan markets in Shanghai and Hankow and the lending market based on biāo qī in Shanxi, continued to be active. Modern banks still needed to participate in these markets to conduct inter-bank transactions and make settlements, which were maintained until structural changes were brought about by the “Great Depression” (1929-1939) and other external shocks. Although the average size of traditional financial enterprises was smaller than that of modern banks, the scale and efficiency of capital allocation could still be greatly improved through the traditional inter-bank market. Some financial version of Coase’s theory of “firms substituting for market contracting” existed. Accordingly, Figure 1 summarizes the evolution of financial organizations in the Ming-Qing eras.

Source: Prepared by the authors based on the bibliography consulted for the preparation of this section.

Figure 1. Principal financial organizations in different periods

Among the two types of organizations in Figure 1, the market organization was on the higher level in Braudel’s terms. Such a structure of organization is also consistent with the “price-efficient markets in goods and services at each step in a commodity chain” composed of “mini-clearing houses.” 34 However, previous studies focused on the circulation of commodities and paid less attention to a similar financial pattern, while commodity circulation and finance often penetrated each other in the type of “Smithian Growth” that existed during the Ming-Qing eras. As may be seen since late Ming times, successful merchants (including modern industrialists) were not keen to expand the scale of a single enterprise but used to finance each other within their relational network and set up different chains of enterprises (lián hào).35 It was also not uncommon for financial institutions, e.g., native banks, to engage in mixed operations or enhance capital penetration in commerce and handicrafts.36 As Braudel has pointed out in his discussion about the form of financial capital in Europe in the pre-industrial era, rich businessmen did not seek for scale but more investment opportunities. It was not until the mid-19th century, when industrialization was underway that this situation was fundamentally changed.37 Similarly, there were wealthy merchants with massive capital networks in Ming-Qing China, but the size of each enterprise was quite limited.

2. Changes in financial technology

New financial technologies, e.g., interest-bearing funds, also accompanied the evolution of financial organizations in the Ming-Qing eras. After the 16th century, a recent phenomenon was that merchants obtained interest-bearing deposits, a form of long-term capital derived from social capital.38 Clans were important providers of interest-bearing funds and interest revenue from lenders. As a result of the taxation system reform in the mid-Ming period, clan members needed to regularly apportion a given tax quota or a silver payment to the individuals who undertook the obligatory corvée labor.39 Thus, funding and demutualization were convenient solutions for clans to handle the taxation reform. The effect of clan funds in local society was further strengthened by the shrinking of the local government’s income, the expanding self-government of grassroots society and the development of mountain areas through partnerships.40 Based on current research, it is still difficult to determine if the fiscal reform and financial innovations were prerequisites for one another, or whether both aspects coincided.41 Regardless of the specific causality, social capital was moved to the financial sector in various forms during the late Ming period.

The interest-bearing fund is also closely related to the evolution of pawnbroking. In the late Ming period, clan funds and family wealth in Huizhou and other places entered the pawnbroking businesses in large quantities as interest-bearing funds. By the Qing dynasty, interest-bearing funds were further linked with the popularity of pawnbroking. With the spread of financial and fiscal technology, public funds from military camps, academies and other institutions, as well as donations for road and bridge construction and charitable institutions, etc., were often deposited in pawnshops and received interest to pay for operational costs. Sometimes the government also operated pawnshops directly by establishing interest-bearing funds. Most counties had several pawnshops, registered with the government. They acquired some official protection and were freed from the heavy taxes once it had been imposed at the end of the Ming era. Even the silver surplus in the Imperial Household Department (Nèiwù Fǔ) was used to operate royal pawnshops, which made loans to salt merchants, copper merchants and other “imperial merchants” with a higher degree of franchise. It is worth noting that pawnshops, although relatively independent as businesses, were interpenetrated by other commercial organizations regarding capital and personnel. In fact, both the pawnbroking sector and the most prominent salt businesses were dominated by powerful Shanxi and Huizhou merchants. Thus, the state’s dependence on interest-bearing funds at different levels actually meant that the state and private economic agents formed an inextricable relationship, while low taxes on financial institutions implied that governments were more dependent on constant bargaining to get fiscal income beyond taxes. These relationships made it impossible for the state to deal with merchants and make economic policies without considering their long-term impact on government operations. Although the interlocking interests between the state and merchant groups could increase rent-seeking, their repeated game would also reduce the official’s short-term opportunistic behavior towards the merchants. This was particularly important for financial organizations whose operations, to a significant extent, depended on their long-term reputation. Therefore, the interaction between financial technology and financial organization helps to understand the accelerated evolution of the financial sector since the 18th century.

In addition to the spread of interest-bearing funds, general innovations in mercantile accounting also had a significant impact on the development of finance. In light of the relationship between double-entry bookkeeping and capitalism emphasized by Werner Sombart and Max Weber, Chinese scholars have long debated whether double-entry bookkeeping existed in Ming-Qing China. However, what we would like to highlight here is the popularity of bookkeeping and its impetus to related financial technologies.

The first prerequisite for bookkeeping to become a common social phenomenon is the popularization of relevant knowledge, which includes not only the professional knowledge of finance but also social knowledge of business customs and individual knowledge about writing and calculation. The wide availability of folk literacy textbooks implies that it became easier for ordinary people in most regions to acquire basic bookkeeping knowledge.42 Mercantile accounting does require more advanced technologies of writing, calculation and accounting. Handwritten textbooks found in recent years from the documents of Shanxi merchants show that traditional commercial bookkeeping had been systematized. Apprentice experience of several years was required to finish the professional education, and only the best of them could have become bookkeepers. Although such commercial education was mainly conducted within the individual shop, mercantile accounting had shown considerable consistency across regions, at least by the Qing dynasty, due to the movement of personnel and the commercial interaction between shops. One major indication is the formation of an accounting system whose core was composed of three types of account books: rough daybooks (Cǎo liú), journals (xì liú), and ledgers (zǒng qīng).43

Nevertheless, the reason why the account book was taken seriously by all interested parties lay in its legal effect as it could serve as official evidence. There are many differences between the Chinese and Western legal traditions, two of which are relevant to this discussion. On the one hand, the importance of documentary evidence in the administration of justice had long been established in China. On the other hand, China’s traditional policies pursued “substantive justice,” which means that the validity of evidence was to be decided according to the specific situations in question, with few legal restrictions imposed on the evidence at hand. From the existing cases of commercial disputes during the Qing dynasty, it had become a routine procedure to gather all the witnesses and check the account books, and many commercial cases could only be clarified with the help of account books. The effectiveness of evidence depended on local customs or shop rules commonly recognized, rather than the specific type of account books. At the same time, such a mass of account books did not seem to present much of a challenge to the interrogators, who were mainly local officials. Since local officials were confronted with various fiscal matters, they were not unfamiliar with the account books and even had a good understanding of them. What is more, private assistants (shī ye) and scribes were also available to provide professional help. However, because checking account books was often cumbersome and time-consuming, officials would not have had enough energy to participate in this undertaking. Therefore, by and large, local officials entrusted the audit task to a private third party, mainly to a specific guild (háng). To some extent, this opened the door to bringing the rules of merchant groups into judicial practice, enabling the commercial customs required for complex financial relationships to have legal effects.

Moreover, compared with discrete documents such as contracts, account books were technically more convenient for providing information or evidence for continuous, repeated and interactive transactions. This was very important for both partnership firms, which were fundamental for conducting commerce from the Ming-Qing eras to modern times, and for the financial networks with which they interacted. Therefore, when the legal validity of the account book was generally established, it also promoted innovation in business and financial technology. An inconspicuous but important novelty was the account booklet. It can be considered a simple and portable account book, usually issued by the shop to regular customers, on which transactions were registered at the time they occurred. Research has mentioned this about one particular business scheme (in Chinese, yìnzi qián), which was similar to a payday loan.44 But recently published documents show that it could also be used for transactions between merchants or between merchants and their deposit customers. Since the account booklet was convenient and designed to record a transaction in the account book of the issuer and the holder’s booklet simultaneously, it was also called a “trust booklet” (píng zhé). It even provided a new form of consumer credit for the customer with a deposit account in a store. The customers could not only obtain the deposit interest, but also purchase goods on credit at the store with free or low interest, eliminating the trouble of withdrawing and carrying cash.

Another major function of account books was the interactive settlement of open accounts. Transferable copper coin accounts (guò zhàng qián) or transferable silver deposits (guò lú yín), two important financial technologies in modern China, were applications of interactive settlements. Although interactive settlements were not defined as a source of liability in litigation during the Ming-Qing period, the commercial practice of transferable accounts had already appeared by the 19th century and advanced the development of financial organizations. For example, it was common practice in Ningbo that native banks sent an account book to their depositors. When a depositor wanted to make transfers to others who had an account in another native bank, he only needed to write down the name of the recipient bank with the payee’s name and the amount of money he wanted to transfer to the account book, and then hand it to his bank. Banks in the city would jointly clear all transfers on the same night, greatly reducing the cost of payment.45 Outstanding balances after mutual settlements across different banks, decided the banks’ cash position. Banks with negative balances had to borrow from those with positive balances, and, thus, inter-bank money markets emerged. In this way, the evolution of the financial organization was combined with the innovation of financial technology.

At the same time, not only account books but also booklets, letters and notes could serve as tools of interactive settlement, as documentary evidence about the practice in Ningbo shows. From the viewpoint of financial development, the most important instrument was the bill. Its advantage over the account book is that it can easily circulate. Such commercial paper can be transferred multiple times before settlement with the dealer, which also greatly improves the efficiency of interactive settlements. However, its disadvantage is that it can be lost or forged easily. The invoicing party still needs to keep the invoicing records or ticket stubs in the account book to protect its own interests. For merchants with a complete accounting system, it was a prudent way to record the corresponding transactions by bookkeeping, irrespective of whether the bill was issued or received. Thus, the account books and the commercial instruments derived from them, especially bills, provided the technical basis for developing an exchange market.

3. Trends in commercial interest rates

In the “Great Divergence” debate, the interest rate difference between the West and China has been frequently discussed.46 However, comparing interest rates is a complicated affair because there were not only various types of loans with different interest rates in China and the West, but the types of historical materials in China and the West are also inconsistent.47 The Chinese interest rates used in current comparisons were mostly ordinary private lending rates, while quotes of interest rates from call loan markets are often used for Europe. The different basis of comparison inevitably led to distorted results. As mentioned above, since the mid-and late Ming era, the development of professional financial organizations and financial markets was not absent. Pawnshops, money shops, exchange banks and inter-bank lending markets emerged one after another and became hubs of commercial capital movement at different stages of financial development. Their activities were closely related to the large, long-distance flows of money and most closely resemble the “highest-level” market defined by Braudel or the capital markets discussed in the literature about capitalism. Moreover, their interest rates are more comparable to the Western European cases. Thus, it is necessary to distinguish the interest rate of the commercial loan from that of ordinary private lending, especially to single out the prime commercial interest rate which can potentially reflect the shift of the efficient frontier of the financial industry.

In fact, in the classical literature describing private lending, the expression “double interest” and criticism of usury are very common. When referring to the activities of merchants, the literary terms “one-tenth” or “two-tenths” are often used to describe the related profit rate. However, these expressions, which have been circulating since the time of the Han dynasty, should rather be regarded as rhetorical formulas. If we look at more concrete and plain historical materials from the Song dynasty to the early and middle Ming period, while the normal interest rate was really high, it was not common for the annual interest rate to reach 100%. Moreover, there was no clear divergence between the interest rate of commercial and non-commercial lending. According to one description during the Southern Song dynasty, interest rates for cash lending were normally 36-60% p.a. and 24-48% p.a. for pawnshop lending, while the grain lending rate could reach 60-100% p.a. These were rates that ordinary people would not complain about and represented levels acceptable at that time.48

Until the mid-Ming period, interest rates remained largely unchanged, at least they did not decline, but a trend shift appeared since then. Wújiāng, located around the economic center in Jiangsu Province, is a good example. Before the late 15th century, the interest rate for grain lending could reach 200% p.a. and 60% p.a. for monetary lending, but by the mid-16th century, the interest rate for grain lending dropped to 48-84% p.a., while it dropped to 24-50% p.a. for cash lending.49 In Huizhou, where the proportion of merchants was particularly high at that time, funds with monthly interest rates of less than 2% appeared. For example, in 1579, the ancestral hall of the Wu family, that had lent the ritual fund at a monthly interest rate of 1.4% to the members for several years, reduced the interest rate to 1% per month.50 Recently, quite a few similar documents have been unearthed.51 In general, the interest-bearing fund of Huizhou that was suddenly established during the late Ming dynasty, constituted a novel financial product in the financial history of China, with an interest rate no higher than 2% per month. The subsequent decline of its interest rate, however, was slow and the spread of this financial product in local societies was rather gradual.

Changes in interest rates during the late Ming period generally occurred in pawnshops. In late Ming times, the interest rates of pawnshops in many areas converged to the level of 20% p.a. or 2% per month.52 These had fallen significantly compared to the common level of 50% p.a. before the mid-Ming period. It not only constituted a driving force for the decreasing interest rates of ordinary private lending but also represented the interest rates of commercial lending generally. In the Qing dynasty, public and private investment in pawnshops through interest-bearing funds became more popular, and the interest rate was generally 10-15% p.a. The interest rate of pawnshops’ lending was still about 20% p.a., but this level had been extended to more regions, and the interest rate of large loans from pawnshops dropped to around 15% p.a. or even lower.53

However, after the 18th century, the financial organizations more critical for merchants to obtain capital were not pawnshops but emerging money shops, lending shops and exchange banks. During this period, the interest rate of 20% p.a. in the standard description should actually be understood as the upper level of commercial lending rates, while the new financial organizations continued to bring it down to lower limits. By the mid-19th century, the lending rates of organizations, especially lending shops and exchange banks, to the benefit of high-quality customers, and inter-bank lending rates could often be as low as about 5% p.a. This was always lower than the borrowing rates of small and medium-sized merchants, and had a wider gap with the rates of ordinary private lending.

In theory, lower interest rates helped to weaken the adverse selection of emerging financial organizations in credit lending compared with the collateralized loans of pawnshops. Moreover, these organizations promoted a variety of centralized transactions and clearing methods. Consequently, each party dynamically matched its cash position with the entire capital network, and its liquidity problems also had to be disclosed to the public directly. Thus, credit transactions of qualified merchants in the network became more efficient and manageable, and the interest rates could therefore also decrease. A typical case of such a capital network was visible in the practice of Xie and Wang families, who were both Huizhou merchants. They traded silk and cloth between Suzhou and Hankow in the late 17th century and jointly established an exchange network, encompassing their relatives and friends who were grain traders. The interest rates of loans due to overdraft amounted to 3-5% p.a., which was far lower than the interest rate of general commercial loans in the same period.54

Unlike the network of relatives and friends, professional financial organizations tried to be financial intermediaries for a broader range of merchants to establish their network. Due to intensified financial connections and cooperation among multiple financial organizations, more institutionalized arrangements emerged, including inter-bank credit based on biāo qī and transferable accounts. As these systems gradually matured in the 19th century, the settlement of transactions between merchants transcended personal networks and improved financial efficiency. Thus, from the 18th to the 19th century, it can be observed that various types of lending with lower interest rates gradually appeared. However, this does not imply an overall decrease in interest rates. Indeed, it is not simply the result of changes in capital’s aggregate supply and demand that lead to lower interest rates. Actually, more specialized financial operators were better organized, and their demand and supply became easier to match with each other. In other words, the evolution of loans with lower interest rates reflected the divergence between the “highest-level” market and the lower level market in Braudel’s terms.

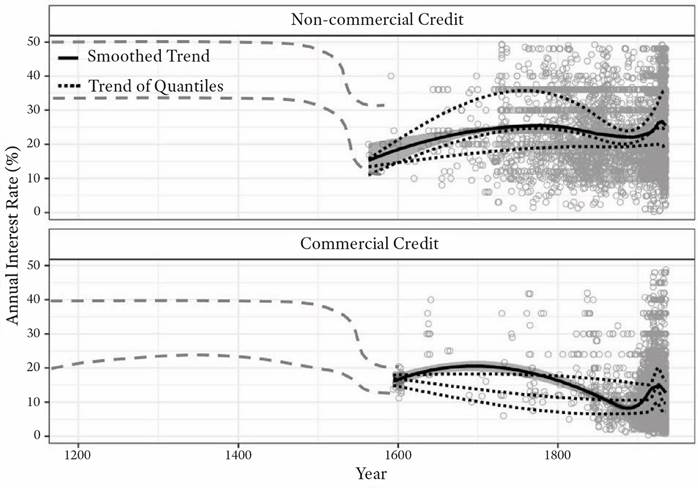

Figure 2 provides an overview of the long-run trends of interest rates. Although China had experienced a “commercial revolution” during the Song dynasty and financial institutions such as pawnshops became more active in commerce, the development of the market economy was suppressed for a long time during the Yuan and Ming dynasties owing to anti-market policies. It was not until the late Ming period that the accumulated economic forces were unleashed, and interest rates suddenly dropped. Interest rates on both ordinary private lending and commercial lending fell sharply, and the latter began to converge to slightly below 20% p.a., diverging from those on ordinary lending.

As to the situation after the 17th century, we have more systematic data to observe the changes in the distribution of interest rates, thanks to the uncovering of new historical materials in the past three decades, especially commercial documents. As shown in Figure 2, the interest rate level of ordinary lending after the 17th century converged to 20% p.a., which was lower than both the upper limit of the standard legal rate, equaling 3% per month or 36% p.a., and the typical level before mid-Ming times. However, instead of continuing the downward trend, the interest rate level was essentially flat or even rose slightly. In contrast, interest rates on commercial lending showed a decreasing trend in the long run. Its average level dropped from nearly 20% p.a. in the 17th century to a level slightly lower than 10% p.a. in the mid-late 19th century, and fluctuations appeared since then due to a turbulent environment and market fluctuations. For the trends of quantiles, the decline in the upper quartile (75%) of commercial borrowing rates was actually insignificant, while the decrease in the lower quartile (25%) was strongest. The downtrend of the lowest part of the interest rate precisely reflects the then existing limits in the evolution of the financial organization and technology, even though observations of this part are relatively scarce before the 19th century. This part represents the prime rates in different stages of financial evolution, and their divergence from the ordinary rates also mirrors that capitalist development was not absent given the economic changes that took place during the Ming-Qing periods.

Source: prepared by the authors based on the bibliography consulted for the preparation of this section. Notes: 1) For periods before the 17th century, broken lines are plotted to show possible intervals. For periods after the 17th century, smooth trends are estimated statistically based on novel historical data.58 2) Commercial credit refers to loans to merchants or financial institutions; the rest is defined as non-commercial credit. 3) “Smoothed Trend” is the LOESS (Locally Weighted Scatterplot Smoothing) trend of the totality of observations, while the shadow next to the trend line represents the 95% confidence interval. “Trend of Quantiles” includes three smoothed trend lines, representing 75%, 50% and 25% quantile trends from top to bottom.

Figure 2. Long-term trends of interest rate (1200-1935)

Regarding international comparisons, the prime interest rate at trading ports in the Yangzi Delta, Shanxi, and the Grand Canal region had dropped to close to 5% p.a. around the mid-19th century. It was still higher than the discount rate on bank bills in Western European countries, e.g., England and the Netherlands, but was not higher than the rate of similar types of interest rates in the U.S. and Japan after the Meiji Restoration.55 In fact, it was precisely during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when modern financial institutions such as banks entered China, that interest rates in the hinterlands rose amid political turmoil, which led to a divergence of interest rates between Shanghai and hinterland ports. Therefore, it is a misunderstanding to attribute the low level of Shanghai inter-bank call loan rates to the influence of foreign banks.56 Of course, there is still room to explain the “Great Divergence” between China and Britain from differences in capital markets since the prime rate in China was still higher than that of Britain. However, the continuous decline and convergence of commercial interest rates until the late 19th century do not support the stagnation view.57 It also suggests that the financial sector in China before the 20th century can hardly be regarded as “pre-capitalist,” and that it is inaccurate to attribute the capital problems that China faced during its “late development” to the limitations of its traditional finance sector.

Conclusion

An “Industrial Revolution” did not happen in Ming-Qing China. Still, during this time, China experienced a wide diffusion of cotton textile production, long-distance fertilizer circulation led by soybean cake from Northeast China since the 18th century, the development of mountainous areas and the planting of cash crops throughout the whole period, etc. Previous studies discussed these changes within the production sphere under the name of “Smithian Growth” but pay less attention to the role of finance. However, this paper finds that the Ming-Qing eras were also a period of innovation in financial technology, the evolution of financial organizations, and a gradual decrease in commercial interest rates.

The financial changes of the Ming-Qing eras appear insignificant if we take the emergence of securities markets, limited liability banks, national debt, or other financial innovations that played an important role in Europe’s early modern financial development as a yardstick. However, as in Europe before the First Industrial Revolution, the key problems and drivers on the demand side should not be ignored. These include not only long-distance trade, which suffered from information asymmetry, but also a need for risk reduction and effective solutions for liquidity problems, which could bring about some changes in the financial sector.59 The drop in commercial interest rates proves the effects of these changes. In fact, the development of the financial sector is a concrete illustration of the mechanism of “Smithian Growth,” and it also shows that its vitality was not exhausted at the beginning of the 19th century or even earlier but continued until the decade of the 1850s.

We also detected that, from the late Ming period on, professional organizations became more important in commercial finance than personal or non-market channels, such as kinship networks. Compared with early modern Europe, the uniqueness of the evolution of finance in the Ming-Qing eras may lie in its relationship to the state. China was the first country to issue paper money, but, in turn, finance was not as important in its state formation. The innovation of financial instruments and organizations had a limited impact on law codes and other formal institutions. Merchants found support from their repeated game with the state. But, as a general rule, it was the local officials who benefitted most. Accordingly, commercial customs formed in financial practices gained certain legal validity through judicial procedures, opening up space for the development of capital markets. The government also provided some protection for the operation of biāo qī or pawnshops when they found it important for their long-term interest or social stability.

However, the state in the Ming-Qing eras never went so far as to become mercantilist. The government followed some financial innovations, e.g., interest-bearing funds, but little innovation came directly from the government’s need. Thus, although the divergence of interest rates between commercial lending and ordinary lending signaled the formation of a higher-level market, it was still difficult to translate the economic power of the merchants into political power. This helps to understand why the financial organization in China was still dominated by a decentralized market network until the early 20th century, when modern banks were introduced into China. It also provides a possible explanation for why China met financial difficulties when the state wanted to launch industrialization, even if its commercial interest rates were not higher than in other late-developing countries such as the United States and Japan.