Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista Facultad de Odontología Universidad de Antioquia

Print version ISSN 0121-246X

Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq vol.23 no.1 Medellín July/Dec. 2011

ARTÍCULOS ORIGINALES DERIVADOS DE INVESTIGACIÓN

Exploration of meanings regarding oral health in a group of pregnant women in Medellín, Colombia. Is there oral health literacy? 1

Cecilia María Martínez Delgado, 2Ana María López Palacio,3 Beatriz Helena Londoño Marín,3 María Cecilia Martínez Pabón,3 Carolina Tejada Ortiz,4 Ludbyn Buitrago Gómez,4 Lina Sánchez M.,4 Jonathan Giraldo M.4

1 Article derived from a research project sponsored by Colgate and

Universidad de Antioquia.

2 Professor at the School of Microbiology, Universidad de Antioquia.

3 Professor at the School of Dentistry, Universidad de Antioquia.

4 Student at the School of Dentistry, Universidad de Antioquia.

SUBMITTED MAY 24, 2011-ACCEPTED: SEPTEMBER 13, 2011

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Cecilia María Martínez Delgado

Facultad de Odontología

Universidad de Antioquia

E-mail address: cmariamar@hotmail.com

Martínez CM, López AM, Londoño BH, Martínez MC, Tejada C, Buitrago L et al. Exploration of meanings regarding oral health in a group of pregnant women in Medellín, Colombia. Is there oral health literacy? Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq 2011; 23(1): 76-91.

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION:in many cultures, mothers are responsible for taking care of their babies, being the mother frequently the most

significant adult, a model to follow, and the principal transmitter of culture, including health knowledge and practices. The objective of

this study was to explore a group of pregnant women’s perceptions of their own oral health and that of their children. These women were

all from Medellín, Colombia, and they were participating in one of the city’s intervention programs.

METHODS:An ethno-methodological

approach was used; therefore, semi-structured interviews were conducted, recorded, transcribed and analyzed, and the responses were

classified according to four criteria: recurrence, divergence, tendencies, and significant meanings.

RESULTS: pregnant mothers give significant

importance to the mouth due to survival and esthetic reasons. They emphasize teeth over other parts of the mouth and think that oral

health is synonymous to healthy teeth. The concept of oral hygiene is represented as cleaning the teeth with toothbrush and toothpaste.

The mouth of their future child is not a matter of concern, and they consider oral hygiene important but not in early stages.

CONCLUSIONS:the interviewed mothers recognize the mouth as an essential survival element. Care of the baby’s mouth gains importance as teeth appear.

Dental floss, which is considered necessary as a cleaning element, is not used by pregnant women, not is it frequent tooth brushing. The

claim of Oral Health Literacy is to build knowledge in order to promote and preserve health.

KEY WORDS:health literacy, oral health, pregnant women.

INTRODUCTION

The family is the primary unit where people are born, grow, and develop their potentials. Historically, it has been the most stable institution, despite the multiple changes it has undergone during the latest decades. It is a place for coexistence, made up of social relations, where the mother is a key element as care provider and culture transmitter; she is par excellence responsible of taking care of the baby,1 and she is the most significant adult in the child’s development because of biological and behavioral conditions.2, 3 Although she is a central figure, other relatives such as grandparents, uncles, aunts or other caregivers offer important support in cases in which the mother works outside the house. All of them transmit culture to the newly arrived family member, and they all stand as imitable models as they communicate behaviors that either favor or hinder individual and collective health.4, 5

Schooling is definitely related to health care; some authors suggest a close relation between parents’ better oral knowledge/practices and frequency of diseases such as caries in their children.6, 7 Therefore, it is expected that parents with better health education positively influence the promotion and conservation of health itself and of their children; it is, the more health education/information the more commitment with its care.

Health literacy is defined as “the capacity of obtaining, processing, and understanding basic information on health”8 , 9 leading to the right decisions for its preservation; therefore, if the family is considered a place for education, where we take care of ourselves and of those who need care due to their conditions of vulnerability—in this case the newborn child—it could be a possible setting for achieving committed parents who can create a culture of health, having better resources to identify when—just to mention some examples—their health is affected, complications exist, or damage or negative events require early intervention by the health services.

Increasing people’s knowledge on health, in keeping with the search for better education strategies, is currently one of the challenges of the health sector staff and of dental professionals in particular, especially when dealing with communities with real socioeconomic disadvantages.

Having parents commit themselves—in spite of these deficiencies—to the establishment of healthy habits and practices5 is one of the missions of the health services, especially when the buccal component is ignored or unattended in groups as important as the mother-child couple, to whom preventive programs should be directed in the first place. Studies conducted in Latin American countries suggest that most expectant mothers ignore the causes of emergence and development of the diverse buccal pathologies and therefore they don’t know how to prevent some diseases in their children.10-13

The objective of this study was to explore a group of pregnant women’s meanings about the mouth, oral health/disease and the ways of taking care of themselves and their children, by conversing in the strict sense of the word, it is, by sharing common popular knowledge, built in interaction in several social settings, and technical-scientific knowledge. The purpose of this exploration is no other than identifying whether Oral Health Literacy is present or not in order to plan education programs that promote meaningful learning in pregnant mothers as the first caregivers; having a better understanding of what happens to them will provide more clarity for the solution of everyday problems, or to resort to instances of greater complexity.

METHODS

Study population

67 women between the second and third trimester of gestation, with normal systemic conditions, participated in this study. They all were connected to the Caja de Compensación Familiar de Antioquia (Comfama) and resided in the city of Medellín. The sampling was of a theoretical nature because the objective was to generate and connect categories by representing conceptions and imaginaries about oral health. The size of the sample was established for convenience. Pregnant women were invited to participate in the interviews during the meetings for dietary supplement provision of the A Good Start (Buen Comienzo) program, led by Alcaldía de Medellín, addressed to pregnant mothers with high nutrition risk.

All of the participants signed a letter of consent containing the conditions about participation in this study and the risks and benefits derived from it. This work was approved by the Committee of Ethics of the School of Dentistry of Universidad de Antioquia.

Semi-structured interviews with five guiding questions were conducted, and they were recorded, transcribed and analyzed. Each interview was about 45 to 50 minutes long. These interviews were conducted by three researchers who were trained for this purpose. The methodological approach used was ethno-methodology,14 which interprets the reality of the facts, situations and events in which people’s lives take place daily. Data saturation was observed when reaching interview #20; at that point, the interviews were stopped. The analysis was carried out following the interviewee’s expressions, by sorting them in terms of recurrences (similar or equal responses); divergences (different responses), meaningful texts (textual phrases that support the recurrences and divergences), and tendencies (tensions and orientations among the discourses, as identified by the researchers, in order to discuss the results).

RESULTS

Socio-demographic data

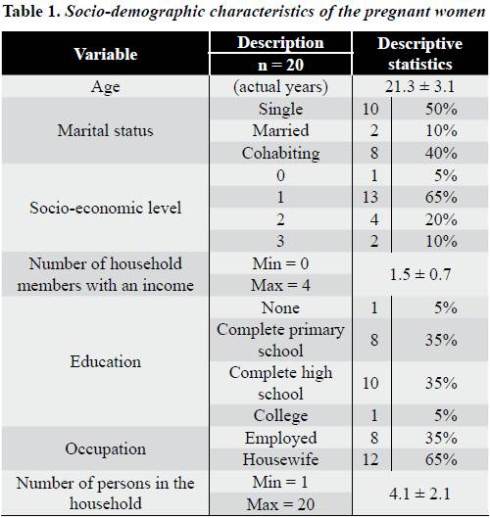

The pregnant women participating in this study are classified, according to the Sisben (Sistema de Identificación de Beneficiarios de Subsidios Sociales), in socioeconomic levels (estratos) 0 to 3.* 50% of them are single women. Household income is usually provided, on average, by two people, but most of them are housewives. Their homes are usually composed by two to six people, a situation which, compared to the household income, clearly shows the precarious conditions for an expectant woman, who at least requires access to nutrition appropriate to her state (table 1).

Data qualitative analysis

Meaning of the own mouth

When the pregnant women participating in this program are asked about what the mouth means for them, standard statements such these emerge:

“Something very important because we eat through it” (E1).

“Having teeth because we use them to eat. If you don’t have teeth, how can you eat?(E8).

Other expressions refer to the first impression one has of a person in terms of personal presentation.

“It is one’s cover letter… see, if you have a job offer and your teeth are ugly, you do not qualify” (E5).

Relation of the mouth [the teeth] to esthetics:

“It is like with the beauty queens, if they have a very pretty body and a pretty face but ugly teeth, they do not qualify”(E1).

“Not having ugly teeth, twisted, like overlapping” (E10, E16).

“Having pretty smooth teeth” (several interviewees)

Other answers associate this meaning to health and disease, as well as to the appropriate care and hygiene of the mouth..

“What does the mouth mean to me? Take good care of it”” (E3, E6, E7, E10, E14).

“Having a healthy, clean mouth”(E10).

Recognizing the mouth as teeth:

“It is the general care of teeth” (E1, E13).

Other structures such as lips, tongue or palate are not mentioned. This association between mouth and teeth as its main structure is possibly due to the mass media. The rest is unknown: pulp, bone, gum. Some difficulty for explaining these concepts is perceived. Besides, some of the answers are suitable for a dentist (dentistry answers), avoiding other possible answers such as feeling flavors, kissing, etc., as if their answers responded to what they think the interviewer wants to hear.

The meaning of oral health

When the interviews go into deeper questions, new statements appear showing the awareness of these women as a result of their experiences; the concept of oral health and disease emerges, in the context of oral hygiene, understood as cleanliness and teeth care.

The answers refer to hygiene and teeth care:

“To me, oral health is hygiene, cleaning my mouth” (almost all the interviewees).

“To me, oral health is what has to do with teeth” (almost all the interviewees).

Other answers include more elaborated systemic concepts:

“Oral health? All what has to do with the buccal system” (E2).

Oral health understood as the opposite of disease was a response given by an apparently more “informed” person:

“With no germs at all, without disease, without plaque, without calculus”(E7).

Or like being healthy with and end or a purpose:

“A healthy mouth so that I can smile and avoid bad odors”(E1).

Esthetic concepts stand out in connection with dental advertising, which usually displays young, good looking, happy, smiley people.

“I hate it when food shows between one’s teeth”(E5).

The issue of breath may be connected to the possibility of socialization, it is a matter of concern due to the effect of rejection or acceptance it may provoke in the closest social circle.

“It is something very important because the smell alone may move people away”(E6).

Oral health and food consumption:

“Good oral health depends greatly on the food you eat”(E2, E13).

The meaning of oral health

These women emphatically link hygiene and teeth cleanliness, meaning adequate teeth brushing.

“Brushing your teeth is the most important” (all of the interviewees).

Mentioning other elements available in the market was not a spontaneous response; specific questions had to be made concerning the necessary elements for oral hygiene. They admitted being aware of dental floss, toothpaste, and mouthwashes. One of them even referred to disclosing tablets:

“Those pills that show you where your brushing was not good” (E6).

Despite the information they have on the necessary hygiene procedures and elements, expressions about using toothbrush and dental floss only, without much regularity, were very frequent, even with statements like these:

“It’s just lack of time”(E12, E17, E18).

“I’d rather rinse my mouth when I get up from bed”(E3).

“I sometimes wash my mouth twice a day… but I am so lazy”(E9).

They also pointed out that hygiene should be made habitually:

“It is like the habit of brushing our teeth three times a day” (E6).

It is significant that some of the interviewees consider that the mouth gets “dirty” only when chewing solid foods; they do not identify liquid foods, such as milk, as a kind of food that gets their teeth “dirty”. They associate solid foods to the necessity of cleaning the mouth; they lack fundamental knowledge on the influence of the diverse food states (liquid, soft, semisoft) and their nutritional content to the process of bacterial plaque formation. Many of the participants associate bacterial plaque to food instead of to the presence of microorganisms, although some of them referred to germs. None of the interviewees referred to sugar as an etiologic factor of caries.

Caring for the own mouth

The participants of this study are aware of the way of taking care of the mouth, as they confidently speak about teeth brushing, its frequency, and the elements necessary for oral hygiene; nevertheless, scarce regularity in the practice of daily tooth brushing is observed, as well as almost no use of dental floss. This is, they do have information that produces knowledge, but without practical effects.

“I don`t use dental floss because I don’t know how to use it”(E16).

“Toothpaste cleans you better and leaves you a good breath”(E12, E20).

Reference to other cleaning products is scarce, apart from the common toothbrush, toothpaste and dental floss; they have heard of the use of crushed coal and bicarbonate, but only two of them had used them at a certain time in their lives. When they were informed of their pregnancy, the ones who used mouthwashes stopped taking them as a personal decision or following professional advice.

The concept of oral disease

All of the interviewees confidently referred to caries and gingival bleeding as oral disease. Nevertheless, when connecting health-hygiene-disease, popular imaginaries prevail over the information received from the mass media or even from health professionals:

“Both nicotine and Coca-Cola damage the teeth”(E3).

Relation of oral disease to stress or bad news:

“My mouth got twisted because of bad news... stress”(E9).

Relation to the state of teeth:

“Not having caries or rotten teeth… ¡how awful!”(E5, E11, E12).

Gums become inflamed for:

“Not using dental floss, because they [the gums] get rotten” (E11).

Dental calculus is not identified as a symptom or as something anomalous:

“I was told I had calculus, but nothing serious” (E15, E20).

Meaning of the baby’s mouth

When asked “what does your baby’s mouth mean to you?” none of the mothers refer to the mouth, they do not approach a defining concept or do not recognize yet the baby’s mouth; some of them identify the matter of hygiene as important, but not during the stage following birth or during the preteething stage.

“They are so tiny… you only feed them with breast milk” (E3, E9).

Nevertheless, when advancing in the questionnaire, the mothers’ anxieties and anguishes about the future baby appear:

“My baby’s mouth? Oh! I hadn’t thought about it” (E2, E5, E14, E18).

“I don’t want my baby with decalcified and rotten teeth liked the ones of my neighbor’s child”(E16).

“It is very important to take care of it, but I don’t know how”(E7, E10, E19).

But at the same time they have positive expectations on their participation in education programs, because:

“I want to learn how to take care of my kid’s mouth and also my grandchildren’s... I have four”(E15).

The baby’s mouth care

At the Health Service Provider Institutions (IPS for their Spanish initials) —where they receive prenatal care— some of the interviewees obtain information on topics related to the oral health/disease of the newborn.

“Mothers may transmit caries because we have microbes… as we are so close to them and we feed them…”(E7, E17).

“...Because we feed them and kiss them… saliva transmits a lot of diseases” (E8, E16, E19).

They have also received information on cleaning the baby’s mouth:

“We were told to do it with boiled water and a clean cloth or gauze all around the mouth” (several of the interviewees).

A contradictory dynamics was found between the IPS’s invitation to pregnant mothers, it is, between institutional stimulus for using the service, and lack of attendance by the women, in spite of the IPS being insistent:

“I have been called several times, but… one is sometimes careless” (E11).

“I do think it is important, but I am lazy…”(E10).

“I have to attend now, because it is a requirement to receive the [dietary] supplement”(E17).

Many of the participants accept that taking care of their future babies is their responsibility; they emphasize that they are the ones in charge of maintaining the best possible health state.

“If one does not take care of her child, who will? (E1, E18).

“I think one has to do it, so that they do not have damaged teeth” (E6).

Some of them also point out the role of grandmothers in attending their children:

“My mom is the one who babysits my kids… I work all day long”(E11).

“My mom taught me how to clean my eldest girl’s mouth; I’ll do the same with the one to be born” (E12).

The mothers expressed the fear of introducing oral hygiene tools in such a small mouth, such as gauze or a fingerstall, by inserting their fingers or the caregiver’s finger in it.

DISCUSSION

Although the mouth is not initially recognized by the interviewees at the very first moment of interaction with them, it is a body part loaded with meanings that emerge or become important as the questionnaires advance, thus approaching meaningful constructions by the individuals as subjects of knowledge. “The mouth has a survival role as it allows food intake, a role of communication and socialization of the humanity, an affective, erotic, sexual role, an esthetic role, a very important role of self-recognition and sensory exploration”, a role, in sum, highly connected to social, affective, sexualerotic, communication and esthetic spheres.15

Escobar et al,16 in their work with pregnant women, reported that the mouth is usually seen as an organ with masticatory and feeding functions, while oral health at the beginning of the life cycle is considered less important, acquiring more relevance, from a social point of view, as kids grow older.

Not recognizing the mouth as a matter of importance may be due to the establishment of value judgments from the perspective of health professionals, who create “academic ideals” of their patients in terms of oral care, in contradiction to what common people consider and this, instead of promoting adherence to oral care, may hinder it.

The health professionals’ habit of reproaching and criticizing, due to the lack of gentler and clearer communication strategies, impedes adequate achievement of prevention as an objective of health education. The scientific discourse arises categorically: “a dental practice, a know-how on the real of the organism, without the symbolic dimension allowed by language…”.17

In addition to a technical knowledge lacking explanations that would provide personal care and kid’s care with meaning, there is also the evident effect of the mass media, with strong emphasis on esthetics, not as a possibility of establishing differences among each of those diverse explanations, but as homogenization of a stereotyped concept of beauty: white and smooth teeth. The question then arises: why patients do not introject the supplied knowledge, constantly displayed and repeated by asking about it, and instead they look so distant from it and from making it part of them? Why this knowledge does not transform them or transcend as to become a habit? They do not believe in it at all?

It seems to be that, even if informed or guided on how to apply what has been learnt, patients, not yet convinced, do not assimilate this knowledge. In relation to this, Moscovici mentions the fixation of social representation as “[…] the mechanism that allows dealing with innovations or having contact with unfamiliar objects […] in order to interpret and make sense of the new objects that emerge in the social sphere”18; it is, the integration of new information or meanings to the existing schemes of thought in a twofold exchange: the new schemes adjust to the old ones and vice versa, leading to “the fixation of the social representation and its object. This process of fixation articulates the three basic functions of the representation: the cognitive function, that allows incorporating the novelty, the interpretative function (of the reality), and the function of orientation of social behaviors and relations”.18

Part of the sociocultural characterization of this group of women refers to poor oral care —although they have a very good personal presentation and good makeup, it is, they are “very well fitted” in popular terms—. We may say then that they do not perceive the mouth as an element that needs care.

The “adjusted” answers provided by some of these women suggest that theirs is a discourse learned from the mass media because no clarity** was observed in some of their answers. Dental advertising usually focuses on caries as well as on the use of toothpaste only, excluding dental floss. Caries is perceived as more dangerous because it is visible, while periodontal disease and gingivitis are not. The concepts of calculus, bleeding, or inflammation do not go any deeper in the issue of periodontal disease as an avoidable problem. Dental professionals do not make enough efforts in this sense either, and therefore pregnant women fail to incorporate oral hygiene habits in their daily lives; consequently, example or imitation do not make part of the promotion of oral hygiene habits among kids.

When people feel lazy about doing their cleaning, they probably have not yet understood that using dental floss is connected to the prevention of oral diseases and tooth loss; they may lack the sufficient knowledge that lead them to this conclusion and therefore to overcome the negative sensation associated to performing this task.

According again to Escobar et al,16 gestation and maternity are stages in a woman’s life that are full of multiple tensions and contradictions, as in the case of a jobless very young mother with low income, an unplanned pregnancy, and without a clear horizon on how to raise her baby to born or already born, for whom the enforced necessity of cleaning her mouth and her baby`s is not a matter of relevance compared to other issues that are much more important and urgent (such as economy, nutrition, family relationships, among others). Additionally, most of the accompanying persons in this study were grandmothers, so their inclusion in this education program was considered instead of the women’s partners. Mother-grandmother relationships are usually difficult too, with consequences for the kid’s care. A negative environment for the adoption of educative practices is observed in terms of concerns and difficulties of the complex family relationships.

Another reason why recognition of the mouth is not usually achieved is the idea that, as during the immediate postnatal period the baby does not have teeth and only feeds from liquid foods (either breast milk or formula) during the first months of life, mothers do not see this situation as a problem to prevent.

The investigators’ clinical practice with people of higher economic and education levels indicates that neither they recognize the newborn’s mouth as a component that must be watched. It seems to be that they have the same minimum information that fails to transcend.

Authors like Gaffield and Weinstein, cited by Saldarriaga et al,19 refer to the willingness of some pregnant women to participate in preventive activities that would help them improve their future baby’s health; as pointed out by Peñaranda,3 pregnant women’s learning depends on two factors: on the one hand, their degree of interest and, on the other hand, their capacity to adhere to what has been learned. Mothers with higher education and cultural levels usually have better learning processes, while it is more difficult to achieve learning in women from the countryside and with lower education levels.

CONCLUSIONS

If the determining factors of oral health as well as the risk and protective factors are widely documented in the specialized literature, what is lacking for the achievement of a healthy population in terms of oral health? Undoubtedly, it is the policy makers’ real recognition of oral health as a close and integral part of health in general. Failing to “set our gaze” on pregnant mothers as a priority population group in the field of oral health would make it difficult to control manageable pathologies; we first should understand that health education happens all through the life and the sooner it starts the more opportunities there will be to stay healthy, with favorable consequences in terms of decreasing health service expenses.

Education has been understood as a means of transformation that facilitates cultural exchange in the field of oral health in order to generate new behaviors with multiple benefits.

The scientific literature suggests a variety of alternatives, such as campaigns to promote healthier nutrition and physical activity to prevent chronic diseases, or the use of free time to prevent addictions, among many other campaigns that would impact health in a positive manner. This is then a long-term endeavor that requires the articulation of diverse strategies where the central characters should not be the ones possessing knowledge if the desirable result is appropriation of new knowledge and practices.

Being Colombia a multi-cultural country, the development of preventive programs requires combination of multiple strategies. Community health didactics is an issue that requires constant reflection in order to provide popular knowledge with sense and meaning so that by articulating it with technical knowledge, all the parties receive benefits. Individual counseling is a strategy that allows approaches between mother, child and the health professional; afflictions flow transformed into questions, a closer dialogue emerges, critical pieces of information are identified—and may be calmly clarified—, and shyness is overcome to make the most of the sessions, no longer than 50 minutes.

1. Blinkhorn AS, Wainwright-Stringer YM, Holloway PJ. Dental health knowledge and attitudes of regularly attending mothers of high-risk, pre-school children. Int Dent J 2001; 51(6): 435-438. [ Links ]

2. Hernández Tezoquipa I, Arenas Monreal M, Valde Santiago R. Health care at home setting: social interaction and daily life. Rev Saude Publica 2001; 35(5): 443-450. [ Links ]

3. Peñaranda F, Blandón L. La educación en el Programa de Crecimiento y Desarrollo: Entre la satisfacción y la frustración. Rev Fac Nac Salud Pública 2006; 24(2): 28-36. [ Links ]

4. Coleta KE, Pereira N, João S, Magnani MB, Nouer DF. The role of pediatrician in promoting oral health. Braz J Oral Sci 2005; 4(15): 904-910. [ Links ]

5. Jackson R. Parental health literacy and children's dental health: implications for the future. Pediatr Dent 2006; 28(1): 72-75. [ Links ]

6. Birkhed D. Behavioural aspects of dietary habits and dental caries. Caries Res 1990; 24 Supl. 1: 27-35. [ Links ]

7. Habibian M, Roberts G, Lawson M, Stevenson R, Harris S. Dietary habits and dental health over the first 18 months of life. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2001; 29(4): 239-246. [ Links ]

8. Glassman P. Health Literacy. [en línea] 2010 [fecha de acceso: mayo de 2010] URL disponible en:http://nnlm.gov/ outreach/consumer/hlthlit.htm. [ Links ]

9. Selden CR, Zorn M, Ratzan SC, Parker RM, Eds. NLM Pub. No. CBM 2000-1. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [en línea] [fecha de acceso: mayo de 2010] URL disponible en:http://www.health.gov/communication/literacy/quickguide/ factsbasic.htm. [ Links ]

10. Saldarriaga A, Saldarriaga O. El médico general y el pediatra en la promoción de la salud oral y la prevención de la enfermedad del niño menor de cinco años y la mujer en período de gestación. CES Odontol 2002; 15(2): 13-20. [ Links ]

11. Zambrano H, Martínez JF, Rubio ML. Guía de Práctica Clínica en Salud Oral. [en línea] 2007 [fecha de acceso: mayo de 2010] URL disponible en: http:///www.saludcapital.gov. co/Cartillas/Cartilla17.pdf. [ Links ]

12. Nowak AJ, Casamassimo PS. Using anticipatory guidance to provide early dental intervention. J Am Dent Assoc 1995; 126(8): 1156-1163. [ Links ]

13. Nowak AJ, Casamassimo PS. The dental home: a primary care oral health concept. J Am Dent Assoc 2002; 133(1): 93-98. [ Links ]

14. Galeano ME. Estrategias de investigación social cualitativa. El giro en la mirada. Medellín: La Carreta; 2004. [ Links ]

15. Alzate T, Campo LF, Martínez CM, Rueda A, Tobón JD. Representaciones sociales de los adolescentes escolarizados sobre la boca y la higiene oral. Medellín 2004. CES Odontol 2005; 18(2): 9-18. [ Links ]

16. Escobar G, Sosa C, Burgos LM. Representaciones sociales del proceso salud-enfermedad bucal en madres gestantes de una población urbana. Medellín, Colombia. Salud Pública Méx 2010; 52(1): 46-51. [ Links ]

17. Cortés N. De lo bucal a lo oral la práctica odontológica: de la técnica al sujeto. Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq 2001; 12(2): 54-58. [ Links ]

18. Lozada M. Representaciones sociales: la construcción simbólica de la realidad. Apuntes Filosóficos 2000; 17(1): 119-131. [ Links ]

19. Saldarriaga OJ, Sánchez M, Avendaño L. Conocimientos y prácticas en salud bucal de las gestantes vinculadas al programa de control prenatal. Medellín, 2003. CES Odontol 2004; 17(2): 9. [ Links ]

text in

text in